Last updated:

‘“Situated Among the Gum Trees”: The Blackburn Open Air School’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 10, 2011. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Sarah Mirams.

This is a peer reviewed article.

The European pioneers of the open-air school movement believed exposure to fresh air, healthy food, exercise and being taught outdoors could prevent the onset of tuberculosis in children. Australia’s first open-air school was established in semi-rural Blackburn in 1915, its students drawn from industrial Richmond. This paper explores the relationship between social and racial concerns and pedagogic ideas in the first half of the twentieth century and argues that the ideals of the open-air movement were adapted to suit local conditions in Victoria.

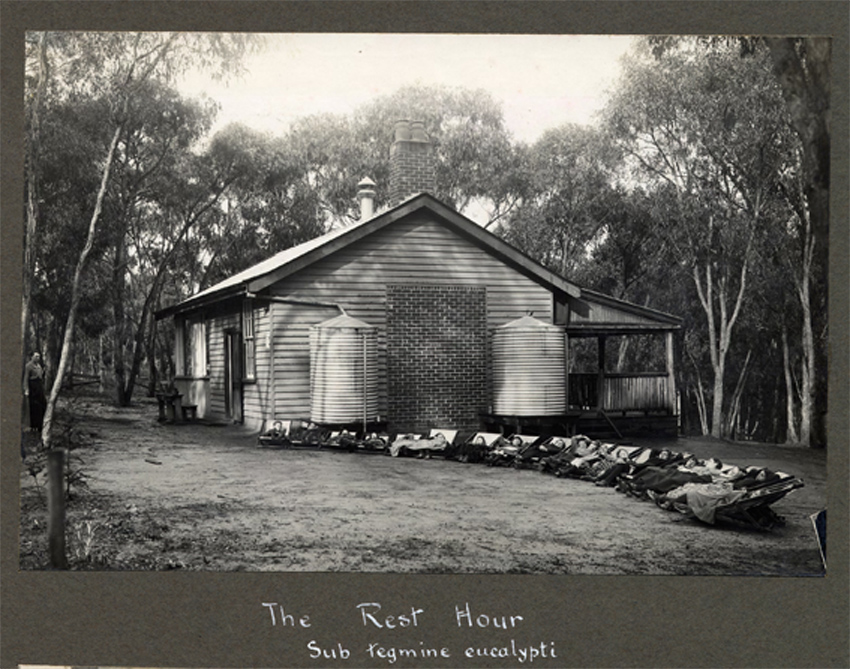

A photograph in the Victorian Education Department’s album ‘Views of schools and school activities 1923’ captures a class of young boys and girls reclining in deckchairs. The children are arranged in a semi-circle around an open, grassy space, their legs swathed in blankets as if there were a chill in the air.[1] Behind them sits a wooden school building. It is a bush scene: eucalypts and scrub surround the school and there are no other buildings in sight. The photograph is entitled ‘The rest hour’, and these are the pupils at the Blackburn Open Air School taking their daily one-hour rest.

During the first half of the twentieth century, thousands of students attending open-air schools in Britain, North America and Europe followed the same afternoon regime. A rest in the outdoor air was one of the features of open-air schools, as was being fed a nutritious diet, being exposed to fresh air and natural light, having regular medical check-ups and being educated close to nature. The first open-air school or Waldeschule (forest school) was established in 1908 in Germany by Dr Bernhard Bendix and Hermann Neufert. This was an experiment in open-air therapy targeted at children living in cities who had been diagnosed with pre-tuberculosis.[2] Similar schools were quickly set up across the developed world. Exposure to the fresh air outside of the congested cities was a common treatment for tuberculosis and there was a general medical belief that those who spent more time outside breathing fresh air were healthier. By the close of World War One the open-air movement was holding regular conferences, with both medical doctors and educationalists presenting research findings demonstrating the benefits of their approach to health.

The Blackburn Open Air School, opened in 1915, was the first of its type established in Australia. This article traces the history of the school and considers to what extent the ideals of the open-air movement were adopted and adapted by the Victorian Education Department to suit local conditions. It is also an attempt to look beyond the carefully staged images of the school captured by the official education department photographer, and to see whether school records held at PROV can provide a more intimate and personal insight into the experience of the open-air classroom for both students and teachers.[3]

‘Hope for Weaklings’

The physical and moral health of the child living in Melbourne’s industrial suburbs consumed the attention of politicians and middle-class reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. City life, it was believed, made children sick, weak and led to ‘the deterioration of the race’.[4] Reformers worked to improve the condition of children living in working-class suburbs such as Collingwood, Carlton and Richmond through public health reforms and the provision of playgrounds, kindergartens, and baby and maternal health centres. A school medical service was established by the Victorian Education Department in 1904 and its officers carried out the first survey of students in the metropolitan area in 1909-10. Among the 3560 children surveyed, 2904 ‘defects’ were identified.[5] The survey found that city children were less fit than their bush cousins, and that children living in industrial suburbs were smaller and weaker and more prone to infection, disease and bad teeth than children in residential suburbs. Inner-city schools were reported in the press at the time as being overcrowded, badly ventilated and filled with ‘puny’ children.[6]

The Blackburn Open Air School was designed to cater for such children. The school came about largely through the efforts of Mrs Keast, the wife of Mr WS Keast, MLA. Mrs Keast was president of the Forest School Committee. Her original vision was to set up three forest schools in Victoria, one to cater for pre-tuberculous children and the other two for students not fit for regular schools.[7] She was inspired by the results achieved at the original forest school at Charlottenburg, Germany, and at the Forest School in London.[8] Described as an ‘enthusiast’ in the press, her committee raised £312 through public subscription to buy two acres of bushland in Gardenia Street, Blackburn, sixteen miles from Melbourne. This land was donated to the Education Department as a site for an open-air school.[9] Blackburn at this time was a young outer suburb with a rural feel; it was a short walk from shops and streets to orchards, flower farms and bushland.[10] The school was described as being ‘situated among the gum trees’.[11] This environment could, it was believed, offer ‘hope for weaklings’, transforming them into ‘perfectly healthy types’.[12]

The students recommended to attend the school were reported to be malnourished, anaemic and underweight, drawn from schools in Melbourne’s most densely populated industrial suburb, Richmond.[13] Janet McCalman’s study of Richmond, Struggletown, describes how in the early twentieth century there were pockets of acute poverty and urban decay across the municipality.[14] Schools and homes were overcrowded, insanitary and infested with vermin; this was an environment where illness flourished. Open-air schools established by education authorities in Britain catered for children living in similar circumstances in London and Manchester.[15] In the eyes of proponents of the open-air movement such environments created moral as well as physical illness. Fresh air, they believed, could cure diseases of both the body and the soul.[16]

One of the things that made an open air-school different from a more traditional school was the classroom, which was exposed, allowing fresh air to circulate freely. The Education Department, inspired by the open-air movement, designed pavilion-style classrooms in 1914. These were wooden buildings with one wall holding a blackboard, the other three walls being open windows with canvas blinds. The woodwork was painted white, giving the room a clean, airy feeling. The children sat in double desks and the teacher taught from a dais. The combination of fresh air and natural light, it was believed, enhanced the children’s health and educational experience.[17] Historian Martin Lawn has argued that school classrooms were designed with built-in values and purposes.[18] The pavilion classroom can be seen to reflect the increasing emphasis placed on fitness, hygiene and nature studies following the passing of the Education Act 1901 and the appointment of Frank Tate as Director of Education.[19]

Three small rooms were attached to the pavilion classroom at the Blackburn Open Air School – a kitchen, teacher’s room and cloakroom. The canvas blinds had, for reasons of economy, been replaced with removable wooden shutters. The ideal open-air school included a bathroom – regular baths were a feature of the open-air regime – but none was built at Blackburn. The size and scale of open-air schools varied widely across the world. The Indiana Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis built a number of open-air or fresh-air schools in the 1920s: these were large brick buildings with sophisticated heating systems and windows draped in muslin. In Milan the ‘Trotter’ residential open-air school catered for 160 children: its facilities included twenty pavilion classrooms, a cinema and a swimming pool.[20] A more prosaic approach was taken in London where twenty-three park bandstands were equipped with awnings and became open-air classrooms.[21] Students in the northern hemisphere often attended classes swathed in coats, hats, raincoats and, in the case of Indiana, ‘Eskimo Suits’ covering their normal clothes to protect them from the snow.[22] The Blackburn Open Air School was a modest enterprise, regarded very much as an experiment by the Education Department. Authorities were curious to discover how the results of their open-air schools would compare with those achieved in the northern hemisphere, where the way of life and the climate were so different.[23]

‘The vivacious young Australian’

The children’s school day began at Richmond Station where they took the train out to Blackburn. Parents were asked to pay for the weekly train ticket at a cost of 1s. 2d. Special rail tickets were issued and the school medical inspectors could approve free rail passes for families who could not afford the fare. It was half an hour’s walk from Blackburn Station to the school. On their arrival the children were given a drink of hot milk and a slice of bread with dripping or jam. Their teacher, Miss Alice Trant, prepared the food with help from a senior girl. Miss Trant was described in a report on her interview for the position as being a skilful teacher, ‘bright, alert and adaptive’, qualities needed for running a school that differed from the traditional state school.[24] Her nursing experience also made her a most suitable candidate. Miss Trant can be seen overseeing the rest hour in the Victorian Schools photograph, standing tall and slender, with dark hair pulled back into a bun, in the shadow of the eucalypts.

The school program at Blackburn closely followed that practised by open-air schools around the world. After the early morning meal there was toothbrush drill, followed by 45 minutes of lessons. Then came recess and play for 15 minutes, followed by 15 minutes of rest. Lessons re-commenced and went for 55 minutes; the students then stopped for a 35-minute lunch of meat or vegetable soup, bread and a milk pudding. Parents who could afford it paid 1s 4d weekly for the meals. The Education Department photograph entitled ‘Food and fresh air’ shows the children sitting on a verandah at desks looking into the bush, eating their midday meal.[25] There is a formality to the image. The children eat off china plates with cutlery; there are cloths on the tables. The meals look substantial and there are spoons laid for the next course. After lunch the deckchairs were set out in the grounds and the children rested, and ideally slept for an hour. Lessons resumed after lunch, lasting for 35 minutes followed by games for 15 minutes, and finally 45 minutes of lessons and singing. The children then walked to Blackburn Station and went home.[26] Students were enrolled in the open-air school for between three and twelve months. They then returned to their normal schools.

Every Friday and Monday the children were weighed and measured and the results recorded on a chart. The records of fourteen children attending the school for twelve months were carefully studied in 1918. All had been suffering marked anaemia and malnutrition when they were first enrolled. The findings were presented to the Minister for Public Instruction and the results were ‘very disappointing’: despite the open-air regime there was no permanent weight gain and the children’s anaemia remained.[27] The Blackburn Open Air School had seemingly failed to match the impressive results achieved by the open-air schools in Britain and Europe.

The report caused the department officials reviewing the open-air program to question whether the practice of removing children from densely populated industrial areas and providing them with fresh air, a hygienic routine and good food could, by itself, overcome anaemia. The Education Department insisted that students attending the school from then on should see a doctor and have their condition, or ‘defect’ as it was called, treated. There was a perceived link between anaemia and either tuberculosis or congenital syphilis; therefore, they argued, the children should be tested for these conditions. This recommendation suggests that when children were first sent to the school little was understood of their medical history. There seemed to be an assumption that ‘wan’, ‘poorly-developed’, ‘weakling’ and ‘delicate’ meant anaemic, a very vague term in itself, and that the open-air regime could ‘cure’ this condition. The term pre-tuberculosis was also ‘interpreted liberally’ during this period.[28] The report also recommended that more meat be consumed during school meals, including black pudding, increasing the iron content in the children’s diet. With the dietary modifications there was a distinct weight gain during the week, but a loss over the weekend when the children were eating at home. The possibility of making the school residential was raised.

The report also identified a problem with the school routine. The children found it difficult to rest, let alone sleep, in the afternoon on the designated deckchair. The report concluded that persuading ‘the vivacious young Australian … to sleep in the day-time’ was well nigh impossible.[29] This hardly tallies with the public image of the ‘delicate’ children attending the school. Despite the charts indicating no measurable physical improvement, the children were reported as being happy, enthusiastic and bright. Both parents and teachers noted that they had shown more energy and vitality since attending the school. With the exception of one student they all attended regularly, even in the cold winters. When asked, they said they enjoyed school. The report struggled to explain these apparent contradictions, concluding that it couldn’t determine ‘what deserves credit for improvement in the children’.[30] Interestingly, the educational progress made by the students was not measured, suggesting it was the improvement in health that most concerned the Education Department.

Perhaps what was working at the school was something the department did not recognise at the time as being a factor in a successful school experience. The children had left cold, overcrowded, run-down classrooms in an industrial suburb and taken a train ride to a small bush school where they were well fed and had plenty of time to play and explore. The curriculum was modified and less rigid than that delivered in a conventional classroom. The children, perhaps less robust than others of their age, might have welcomed a break from the hurly-burly of the overcrowded Richmond classrooms. Janet McCalman argues in Struggletown that the most common barrier to working-class children’s learning was lack of self-esteem.[31] At the Blackburn Open Air School, Miss Trant, that skilful teacher, worked with this small group of children for six to twelve months. Perhaps she was one of those teachers who could inspire and encourage her pupils. In 1918 the Education Department did not measure student engagement and self-esteem as it does today, but perhaps what the school offered was not so much a means of healing their physical ills as the opportunity to develop their confidence and sense of self-worth.

This is only guesswork. To get a sense of how teachers, students and parents might have experienced the Blackburn Open Air School it is necessary to delve deeper into the historical record. Historian Phillip Gardner, in his study of English career teachers, makes the point that it is difficult to re-create the experience of the classroom owing to the dearth of historical evidence beyond that of public pronouncement and policy.[32] Teaching is also an intensely private and solitary craft.[33] In the case of State School 3850, the correspondence and building files held at PROV provide glimpses of the workings of the classroom in Blackburn. This is not an extensive collection – the complete files fill only one archive box – but nevertheless it provide snapshots of the conversations between the teacher, Education Department and parents over a thirty-year period.

‘They are not too delicate to make a nuisance in general’

When Maisie Coutts came home to Dover Street Richmond with bruised fingers, her mother wrote to complain to the Education Department. Mrs Coutts was concerned about the caning and about Maisie having being singled out for punishment for being talkative in a classroom of noisy children. She was also worried that if she complained to Miss Trant, Maisie would be ‘sent back to Richmond’.[34] She didn’t want this to happen, as her daughter’s health had improved at the school. The department acted quickly, interviewing Miss Trant and reprimanding her for using corporal punishment, which was against the regulations at open-air schools. Miss Trant was suitably contrite.[35] The letter, in a perverse way, was an endorsement of the school, which had been running for nine years when this letter was sent.

The correspondence files for the Blackburn Open Air School include a number of letters from parents requesting that their children be admitted to the school. Mrs W Fitzpatrick wrote to the school medical officers in 1939. Her children Maisie and Teddy, students at Cremorne Street School, had been sick over the school holidays and were ‘very thin’.[36] George Bayley had spent four years in a sanatorium and was no longer infectious. His father, a returned soldier, ‘realised the importance of further education to his son’s success in life’ and asked that he be allowed to enrol at the school.[37] The mother of twelve-year-old Victoria Hassett, a Central School Richmond student recently released from a sanatorium, also requested a place at the open-air school.[38] Mrs P Phillips asked that her son Phillip, a student at Burnley State School who was recovering from whooping cough, be enrolled. The air in Melbourne, she wrote, ‘did not suit him’.[39]

These letters suggest that Richmond residents were familiar with the school and its purpose and that the parents who sought better opportunities for their children at the school did not fit the stereotype of the hopeless, hapless slum parent propagated in the press. In the eyes of social reformers, slum life was synonymous with crime, neglect and intemperance: there was a moral stigma attached to living in Richmond.[40] ‘Teacher mothers delicate children’ announced the headline in the Herald on the opening of the school. Miss Trant was described as the children’s ‘foster mother’, an expression suggesting their own mothers were incapable of fulfilling that role.[41] Yet in 1918, 75 per cent of the parents were prepared to pay for the meals and train tickets required for attendance at the school. They were most likely among the many respectable poor who found themselves by misfortune living in the decaying suburb.

Richmond’s reputation did follow the children into leafy Blackburn, however. Herbert Langdon, who lived in Gardener Street, wrote an outraged letter to the department in 1926 complaining about the students.

What with stone throwing, jeering at the clothes line and making themselves generally offensive… This is a good class of street with Modern houses and good class residents… These children who I understand are from the poorer suburbs by their behavior constitute a menace to the place… The burden of taxation is heavy enough without the extra burden of having to tolerate ill mannered and slum behaviour… these children are supposed to be delicate but they are not too delicate to make a nuisance in general.[42]

Miss Trant angrily denied these claims, claiming Langton was aggressive to all he came in contact with. Even if he was a serial complainer his targeting of boisterous behaviour as ‘slum like’ confirmed the stigma that Richmond residents had to live with. A more bizarre accusation came by way of a telegram sent to the department warning that there was a rumour circulating that the girls from Blackburn Open Air School were ‘under orders to appear in Melbourne streets dressed as boys’.[43] The telegram, signed F Copeland, Blackburn, said there was much local feeling against this and demanded the orders be ‘counter-minded’. This was dismissed by the Education Department as being ‘malicious’ and suggested there were those who perhaps were less sympathetic to the school and its students. Richmond’s reputation as a slum was officially confirmed in 1936 when it, along with other suburbs within a five-kilometre radius of Melbourne, became the subject of government attention with the establishment of the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board.

Primary school correspondence also throws light on the teaching experience at Blackburn. The Maisie Coutt incident, which involved either a cane or a duster depending on whose version of events you believe, suggests that Miss Trant had to do more than ‘mother’ her delicate children. There were many teachers in rural schools who, like Miss Trant, were teaching in single classroom schools, but they generally had the support of local communities. She however was the only teacher in a school dedicated to the open-air movement, and as such her experience was unique. She requested an upgrade in her classification in 1931, arguing that although the numbers she taught were the same as in a rural class, there was much more work. This was largely because of the diverse nature of her students, whom she described as ranging from ‘retards, defaulters, Opportunity Grade Scholars’.[44] She therefore needed to prepare a lot of individual work to cater for a range of abilities. Her request was denied.

Miss Trant also argued that her additional qualifications in First Aid and Cookery entitled her to a change in classification. A significant part of her day was dedicated not to teaching, but to organising the dietary component of the open-air routine. She was responsible for ensuring up to twenty-seven children were given hot drinks and a hot meal every day. This involved ordering food, keeping the wood fire going and supervising the assistant in cooking, serving and cleaning. Whereas most school correspondence files are filled with orders for books and maps, the Blackburn files are replete with butcher’s bills and grocery order forms.[45]

The other cornerstone of the open-air school was the open-air classroom. Alice Trant worked at the school from 1915 to 1943 in the same pavilion-style classroom erected in 1915. The only significant addition was a verandah, built in 1921, where the children were photographed for the Education Department album, sitting at their desks eating. Presumably the verandah was a place where the open air could be enjoyed and the sun avoided during the summer months. When Mrs Dorothy Hamilton became head teacher in 1943 she wrote a number of letters to the department complaining about the building. One stated that the condition of the verandah and asphalt was such that the students were largely confined to the classroom for much of the winter.[46] She also requested that a gas ring be installed in the kitchen. This would replace the large wood stove, which was kept alight all day to heat milk for the ‘undernourished children’, and made the kitchen unbearably hot in summer.[47] She asked that a fireplace be built in the classroom so the children could warm themselves up after their long walk from the station in winter. In 1947 she requested that an electric light be installed as the gum trees that surrounded the building made the classroom dark and gloomy.[48] By this stage the canvas blinds had been replaced with glass, so the building was looking more like a normal school room.

After the years of depression and war many schools in Victoria were similarly run-down and required urgent repairs. The correspondence in the building files does more than record wear and tear though: it questions the ambitious claims made by supporters of the open-air classroom. A number of pavilion-style classrooms were built across Victoria as new schools from 1914. Seen as a cheap option by the department, they were universally condemned by teachers as ‘freezing chambers’ and ‘draughty sheds’.[49] While Miss Trant appears to have embraced the philosophy of the open-air classroom, her successor was less enamoured with its architectural elements. That is not to say the open-air philosophy had been completely abandoned: the afternoon rest in the deckchairs, the physical training and the meals remained as part of the school routine.

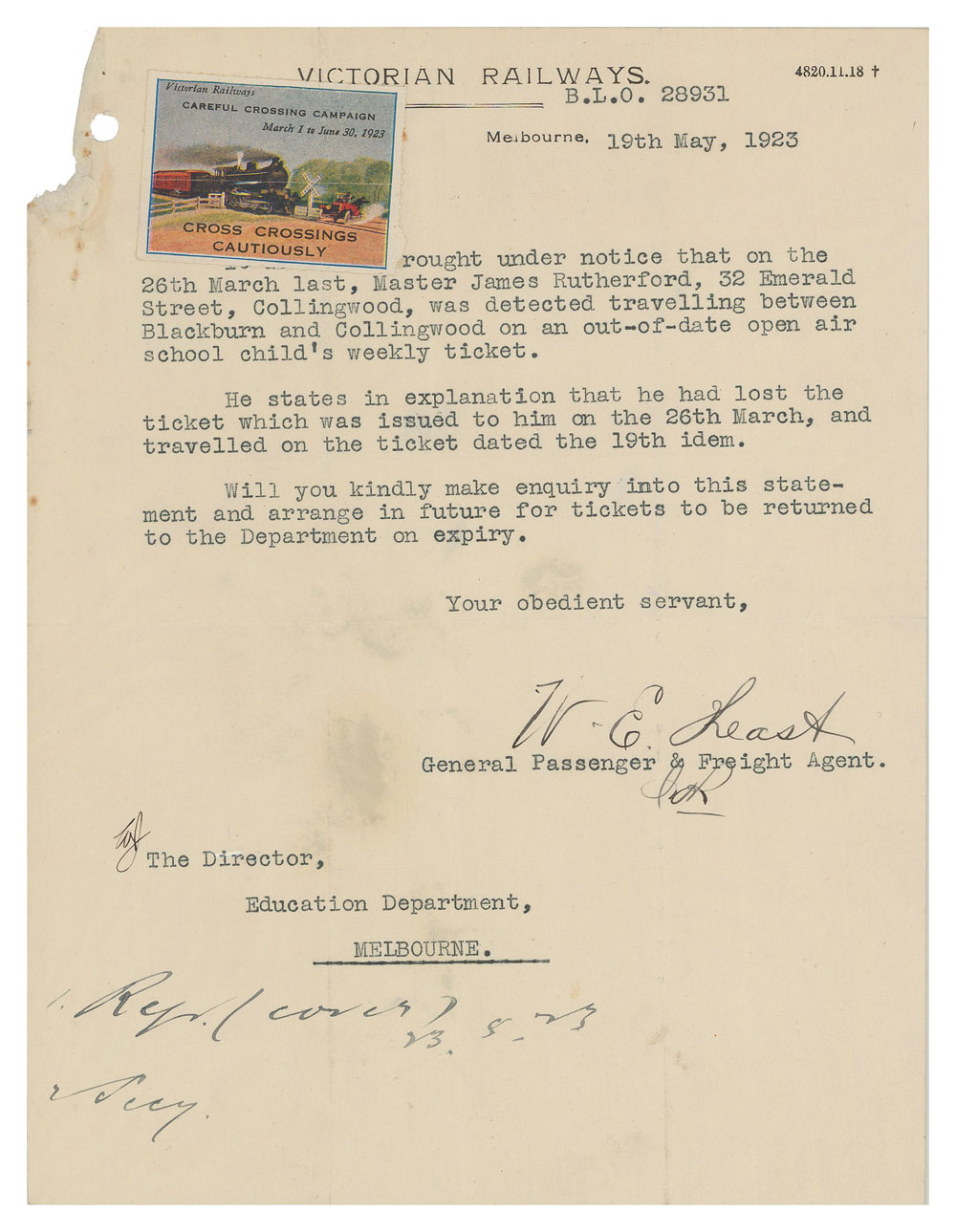

The voices most absent from the historical record are those of the children themselves. There were a few class lists of students, giving their names and addresses and some correspondence from parents and the department. We know about talkative Maisie and a boy called Master James Rutherford who was detected travelling on an out-of-date open-air school child’s weekly ticket in 1923.[50] Roy Brewer was sent to Blackburn Open Air School in 1928 and three years later Miss Trent wrote to the department requesting advice on his future training and employment. His best subjects were handwork and drawing and he was sent to the Vocational Guidance Officer.[51] This is the most detailed letter about a student in the files, and yet it presents more questions than answers. Why, for example, did Roy attend the school for three years when students were supposed to stay for months rather than years?

The criteria for sending children to the school were not made clear in the school records. Words like ‘undernourished’ and ‘delicate’ were used, as were ‘retarded’ and ‘vivacious’. The answer lies with the medical officers who made the initial recommendations, but their records have not been located. It could be that these doctors working within these communities used their discretion and sent children to Blackburn for a variety of medical and social conditions.

Conclusion

The Blackburn Open Air School shared many features of open-air schools around the world established in the first half of the twentieth century, although it counted itself amongst the more modest in its architecture and scale. Why other open-air schools were not established in Victoria was not explained in the files consulted. The lack of dramatic improvement in the children’s weight in 1918 may have discouraged further experimentation and an expansion of the scheme. Another possible explanation could be that there was not a pressing need for such schools by the 1920s. Melbourne never had the large slum populations of British and European industrial cities nor their rates of tuberculosis. With the growth of suburbia the city populations dispersed and the rates of general health improved.

Most open-air schools in Europe and North America closed or went into decline with the development of antibiotics, which provided a cure for tuberculosis. Blackburn Open Air School continued to operate until 1964. The school appeared to fulfil a need for those children who lived in the decaying inner suburbs of Melbourne. Further research into the public record may well reveal stories of the children sent on that journey to Blackburn, however the records for the years 1947-64 have not been located, so little is known of the school’s history after the Second World War. Interestingly, the open-air pavilion classroom in Blackburn did continue to play a role in the health of Victorian students: it was extensively modified and became a centre for the Education Department’s Psychology and Guidance Branch.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 14562/P6 Micellaneous Photographs … [Education History Unit], Unit 5, ‘Views of schools and school activities’, page titled ‘An open-air school for anaemics’.

[2] A-M Châtelet, ‘Open air school movement’, in Encyclopedia of children and childhood in history and society (accessed 20 May 2011).

[3] This article uses the form ‘open-air’ when discussing the movement or the schools in general. The use of the hyphen appears to vary, with some schools, such as Blackburn, omitting the hyphen in their names.

[4] G Davison, ‘The city bred children and urban reform in Melbourne 1900-1914’, in P Williams (ed.), Social process and the city, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993, p. 149.

[5] LJ Black (ed.), Vision and realisation: a centenary history of state education in Victoria, Education Department of Victoria, Melbourne, 1973, vol. 1, p. 1172.

[6] Sydney morning herald, 19 June 1912, p. 5d.

[7] ibid.

[8] ‘Delicate children. Proposed Forest School’, Barrier miner (Broken Hill), 25 November 1911, p. 8c (quoting The Age).

[9] School Medical Officers, ‘The open air’, Education gazette and teacher’s aid, 22 January 1914, p. 23.

[10] D Sydenham, Windows on Nunawading, Hargreen Publishing Company in conjunction with City of Nunawading, North Melbourne, 1990.

[11] Argus, 3 January 1928, p. 8f.

[12] PROV, VPRS 640/P1 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 1523, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1914-16), news cutting, ‘Teacher mothers delicate children: Open-Air School at Blackburn’, Herald, c. 1915.

[13] The first intake came from the East Richmond, Richmond, Glenferrie and Burnley state schools. Later Collingwood students also attended. Education Department medical officers recommended which students should attend.

[14] J McCalman, Struggletown: public and private life in Richmond 1900-1965, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1984, p. 14.

[15] M Cruikshank, ‘The open-air school movement in English education’, Paedagogica historica, vol. 17, no. 1, 1977, p. 67.

[16] G Thyssen, ‘The “Trotter” open-air school, Milan (1922-1977): a city of youth or risky business?’, Paedagogica historica, vol. 45, no. 1, 2009, p. 160.

[17] School Medical Officers, ‘The open air’, p. 23.

[18] M Lawn, ‘Designing teaching: the classroom as technology’, in I Grosvenor (ed.), Silences and images: the still history of the classroom, Peter Lang Publishing, New York, 1999, p. 73.

[19] Vision and realisation, vol. 3, p. 322.

[20] Thyssen, p. 162.

[21] Cruikshank, p. 67.

[22] Indiana State Library, ‘Open air schools in Indiana’ (online exhibit accessed 20 May 2011).

[23] ‘Report of the Minister of Public Instruction’, Victorian parliamentary papers, Session 1918, vol. 2, no. 10, section V, ‘The open-air school’, pp. 23-6.

[24] PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 1523, Item 3850, notes on applicants for the position of head teacher to the Blackburn Open Air School, 18 February 1915.

[25] PROV, VPRS 14562/P6, Unit 5, photograph ‘Food and fresh air’.

[26] ‘Report of the Minister of Public Instruction’.

[27] ibid.

[28] Thyssen, p. 159.

[29] ‘Report to the Minister’, p. 25.

[30] ibid.

[31] McCalman, p. 76.

[32] P Gardner, ‘Reconstructing the classroom teacher, 1903-1945’, in Silences and images, p. 125.

[33] ibid., p. 127.

[34] PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 1845, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1927-29), letter to Education Department, Mrs Coutts, 170 Dover Street Richmond, 7 November 1929.

[35] PROV, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books, Primary Schools, Unit 810, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1915-37), memorandum for Miss A Trant, 20 November 1929. Corporal punishment was banned in Victorian government schools in 1985.

[36] PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 2290, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1936-39), Mrs Fitzpatrick to Department of Education, 4 February 1939.

[37] ibid., Unit 1745, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1924-26), Public Health Department to Education Department, 25 November 1926.

[38] ibid., Unit 1523, Item 3850, request to Medical Officers from Mrs Hassett, 113 Church Street Richmond, 18 February 1916.

[39] ibid., Unit 2290, Item 3850, request to Medical Officers from Mrs P Phillips, 355 Burnley Street, 30 November 1938.

[40] McCalman, p. 47.

[41] PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 1523, Item 3850, news cutting, ‘Teacher mothers delicate children: Open-Air School at Blackburn’, Herald, c. 1915.

[42] ibid., Unit 1745, Item 3850, letter from H Langton to Education Department, 6 July 1926.

[43] ibid., Unit 1523, Item 3850, telegram from F Copeland, Blackburn, 1 November 1917.

[44] ibid., Unit 1949, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1930-32), request to the Secretary, Miss A Trant, 8 January 1932.

[45] Butcher’s shop receipts in PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Item 3850, various units.

[46] PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 795/P1 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 2887, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School, application for repairs to school, 11 February 1947.

[47] ibid., letter from Mrs D Hamilton, 20 November 1943.

[48] ibid., application for repairs to school, 11 February 1947.

[49]. Vision and realisation, vol. 1, p. 330.

[50] PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 1666, Item 3850 Blackburn Open Air School (1921-23), Victorian Railways letter, 19 May 1923.

[51] ibid., Unit 1949, Item 3850, letter regarding Roy Brewer, 8 July 1931.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples