Last updated:

‘Piggoreet: A Township Built on Gold’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 12, 2013. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Joan Hunt.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This paper is based on an historical investigation into a township whose existence relied totally on the gold-mining industry and focuses on the decade 1861–1871. As a society we need to know more about the nature of daily life during the deep-lead mining phase, and the domestic and working lives of families on rich deep-lead Victorian goldfields in a time of intense social change. Piggoreet was a township within the Springdallah goldfields about which the only published history is a thirty-two page booklet written in 1926. Yet it had high-yielding mines which provided employment for its families, numerous enough to have more than three hundred children enrolled in the school at the end of the 1860s. After establishing the background to Piggoreet becoming a township, this paper describes one decade during which the deep-lead gold-mining industry was at its peak. It draws on a database created from an extensive range of primary and secondary sources to reveal the functional, social and economic life of the community. The now-disappeared township can be reconstructed using the database as well as a range of other government, church and community resources as evidence. The database has enabled analysis and interpretation of the mass of information. Some idea of the physical structure of the township becomes possible, and the symbiotic relationship between the gold-mining industry and the families reliant on it is revealed.

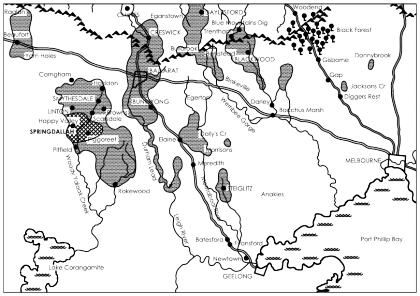

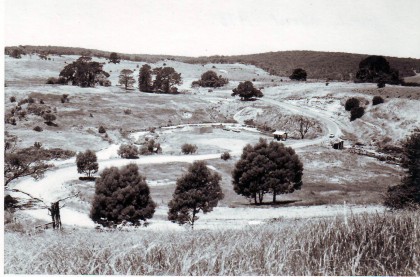

The official discovery of gold in the newly constituted Colony of Victoria in mid-1851 had an enormous impact and far-reaching consequences for Australia and its development economically, socially and politically. Not least of these consequences was the population explosion that led to the growth of towns and cities undreamt of just a few years previously. Piggoreet was one of the many extraordinary towns that sprang into existence in the mid to late nineteenth century because of the discovery of rich auriferous ground on which it came to be built. Prior to 1852 the district was virgin bush occupied for tens of thousands of years by the Wathaurang people. Today it is almost exclusively sheep-grazing land. The site of now non-existent Piggoreet is in the Golden Plains Shire, approximately 153km (95 miles) west of Melbourne, 37km (23 miles) south-west of Ballarat, and 16km (10 miles) south of Smythesdale, straddling the Woady Yaloak and Springdallah creeks between Linton and Cape Clear. The spectacular natural geological formation traversed by the creeks, once known as Paterson’s Crescent and later as the Devil’s Kitchen, is a relict ‘fossil’ landscape whose now-diminished mullock heaps, gorse-covered disturbed ground, altered water-courses, eroded gullies and springtime bulbs blooming in roadside paddocks provide ample cultural landscape evidence of an abandoned township.

When 28-year-old Herbert Swindells stepped ashore at Corio Bay in 1848 as a convicted exile from Britain, he little knew of the exciting role he was to play in the creation of Piggoreet. Born in Cheshire in 1819 and well educated, on 17 March 1846 he was convicted at the Stafford Assizes of forging a promissory note for £25 to liquidate his debts. He was sentenced to seven years transportation, but while in Millbank penitentiary accepted the opportunity to become an exile.[1] Offered only to those of good behaviour and repentant demeanour, Swindells received a conditional pardon, effective upon disembarkation from the Anna Maria at Geelong on 23 June 1848.[2] His name appears on a list of ‘Exiles who have distinguished themselves by exemplary conduct during the voyage’.[3] Within weeks of arrival he had established himself as an engrossing clerk and accountant in Geelong, shortly thereafter becoming a teacher at the Presbyterian school.[4] A presentation of books and money was made to him by the parents at the end of 1849.[5]

Concurrent with the establishment of the Colony of Victoria on 1 July 1851 was the official recognition of the discovery of gold at Clunes.[7] An influx of ships under sail had begun arriving at Port Phillip, eventually bringing to the new goldfields tens of thousands of immigrants from other Australian colonies, California, China, Britain, and other parts of Europe.[8] Early in January 1852 news seeped into Geelong that ‘sufficient gold to pay well for working’ had been found in the Spindella Creek.[9] This location was described as being a mile and a half from the ‘Wardiyallock’ river near Mr Brown’s home station; this was close to present-day Scarsdale. A consortium of Geelong businessmen formed the Gold Exploration Committee, whose aim was to encourage some of the incoming gold-seeking traffic through Corio Bay and Geelong rather than through Port Phillip Bay and Melbourne.[10] On 9 June 1852 they decided to send a party of four volunteers and a superintendent to try to discover a paying goldfield on the lower reaches of the Woady Yaloak Creek (which had a variety of spellings, and was also known as Smythe’s Creek) with Herbert Swindells as superintendent.[11] The five men with their bullocks and drayload of canvas, tools, equipment and stores sufficient for three months set off from Geelong on 22 June 1852. Swindells maintained contact with the Geelong newspapers, no doubt via messengers at the Emu Inn at Old Pitfield where the road to the Western District crossed the Woady Yaloak Creek. The letters refer variously to the party’s address as Paterson’s Crescent, Mount Yeerup, Spindella Creek and Wardiyallock. One letter dated 7 August 1852 stated that the party had ‘tried the surface earth in several places in Paterson’s Crescent, and have invariably obtained gold’.[12] Another described the flat below a natural amphitheatre, which Swindells had named Paterson’s Crescent, and the beds of the Spindella and Wardiyallock as potentially ‘highly remunerative’ if sufficient numbers arrived to develop the resources of a goldfield.[13] The Gold Exploration Committee regarded Swindells’ reports as indicative of success, and paid a promised bonus to the party, along with any gold they had found, plus £1 per week wages. When, in 1864, the Victorian Government appointed a board to consider applications for rewards for the discovery of new goldfields, Herbert Swindells received £100 as the official discoverer of the Woady Yaloak goldfields.[14]

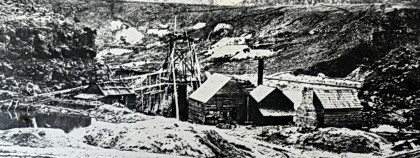

At the end of 1853 a report of ninety ounces of gold being washed at Paterson’s Crescent showed that the shallow alluvial diggings there were proving lucrative.[15] Sporadic reports gave evidence of continuing interest: ‘Springdallah … is looking brisk and will certainly become a standing diggings; it is a beautiful spot to reside upon’.[16] About this time changes were occurring in the goldfields. The era of shallow workings by one or several men was passing as the easy gold was worked out, and the scene was set for working the deep leads by capital-rich mining companies. Exploitation of those deep leads, complicated and costly, required capital to fund the shaft sinking and underground tunnelling, the infrastructure of poppet heads, machinery, steam-engine houses, horse puddling machines, water pumps and sluice apparatus, and the employment of miners and support workers.

In September 1859 the earliest deep-lead alluvial company, the Try Again, acquired a forty-nine-acre lease in the Devil’s Kitchen, and drove the first tunnel into the cliffs. By this time, Paterson’s Crescent had become the Devil’s Kitchen, Mount Yeerup had become Mount Erip, and the Spindella had become the Springdallah Creek. The Springdallah Quartz Company erected crushing machinery at the Devil’s Kitchen by mid 1861.[17] It was the only quartz mine among many alluvial mines in the district. The Try Again and the Alpha companies together occupied a total of sixty or so acres enclosed by the ‘frowning, rugged, moss-covered walls’ by September 1864.[18]

The ‘township’ that had started to develop near the junction of the Springdallah and Woady Yaloak creeks consisted of about thirty wooden houses and a Church of England by the early 1860s.[19] It was reported that ‘within the last twelve months quite a large population has sprung up there, and the impetus given of late to mining in the district has had the effect of imparting to that township a business aspect’.[20] There were non-mining families living in the area as well, those of the squatters who occupied tens of thousands of acres of grazing land. David Clarke had occupied Piggoreet West since 1854 and his son John was living on the Emu Hill run south of Linton. John Clarke was married to the daughter of William Newcomen who owned Moppianamum north of Scarsdale, the squatting run that had earlier been held by John Brown. These families continued to live and work their properties while the miners roamed and fossicked and set up companies among the hills and gullies on Crown and private land alike.[21]

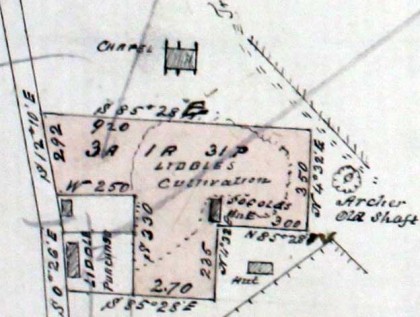

No research sources exist prior to 1860 for Piggoreet, but a combination of primary and secondary records provide direct and inferential evidence about the gradual development of the settlement from the temporary bark and calico camps of the mid 1850s to the commercial centre with bluestone guttering and verandahs of substantial buildings and institutions which eventually formed the township a decade later. Records which reveal demographic evidence and family constellations include birth and death certificates, baptism and burial records, coroner’s and fire inquests, mining company shareholdings and other mining records, council minutes, land selection files, wills and probates, vaccination records, a wide range of maps and plans, school registrations, newspaper reports, and court records. These sources have provided strong evidence for the make-up of the hundreds of families living in Piggoreet in the 1860s. The town provided all the services and domestic supports that a family would require, given the period and circumstances. There were hotels such as William Chubb’s Coach and Horses on the approach road to Piggoreet, John and Jane Liddell’s Try Again at the start of the main street, Martha Gaten’s Archer Hotel, Henry Coe’s Court Royal, Edward Hall’s Royal Mail, a beer house known simply as Sharp’s Hotel, belonging to Seth Sharp who owned and drove coaches and carriers’ wagons, Solomon Cox’s Atlas Pic Nic on the Tableland overlooking the township, and William Cross’s Corner Hotel.[22] In the early 1860s publican’s licences were granted to other Piggoreet residents such as Robert Vincent and Mary O’Brien who had smaller, unnamed beer houses, but it was at the major hotels that Cobb & Co coaches discharged and loaded their passengers and goods.

Spread along the main street of Piggoreet and leading over Irvine’s Hill into the Devil’s Kitchen to the south were the Union Bank, a court house and police station, the Mechanics’ Institute, the post office and savings bank, and a school.[23] On top of Irvine’s Hill was Joseph Gartside’s general store, opposite the Court Royal Hotel. Further south, the Church of England stood atop Paul’s Hill above the Devil’s Kitchen, one of several churches in Piggoreet during the 1860s. A Primitive Methodist church existed at that time, the Presbyterians had their church near the back road to Derwent Jack’s, and the Wesleyan church was on Sugarloaf, just near the Common school. Piggoreet Common School No. 726 was erected on the side of Sugarloaf Hill in 1863, designed for 200 children, and granted aid from 1 January 1864 when head teacher Benjamin Scott had 66 children enrolled.[24] Members of the six-man school committee in 1866 included the local squatter David Clarke, William Maughan who was manager of the Try Again mine, Rev. William Campbell Wallace who was a church minister, William Irvine who ran a large store on top of the hill that bore his name and separated the township from the Devil’s Kitchen, George Woodhouse who was both the deputy registrar of births and deaths and chemist-shop owner on the road into the town, and George William Paul the butcher.[25] The peak year was 1871 when 334 students were enrolled, 183 boys and 151 girls. Robertson claims there must have been nearly a thousand houses within half a mile of the school by the end of the 1860s.[26]

William Pattinson had a drapery store in the main street, near Donald and Mary Jamieson whose home and blacksmithy was next to the Try Again Hotel. A general store was run by the partnership of Holleson and Alpen, and Southward and Simpson were grocers. McCormack (who was in charge of the drum and fife band) was a saddler next to Jamieson’s. Other residents included Thomas Foster, the doctor who lived on the road to Happy Valley overlooking the Piggoreet township, and who attended the births, illnesses, accidents and deaths of local residents for several decades, Edwin Moon, manager of the Archer mine in the 1860s who lived on the corner of the Sugarloaf road, and Asmus Japp who was in business as Japp and Johannsen undertakers and carpenters at the southern corner of the turn to Happy Valley. These men and their families were mostly English, Scottish, Irish, Welsh, German and Swiss-Italian, and exemplified the mix of nationalities from various backgrounds, countries and cultures being thrown together without preparation, and able to create a community of their own making.

By far the greatest number of English were from the north: Cumberland, Durham and Northumberland, with very few Cornish attracted to Piggoreet. For instance, of a sample of 100 births registered between March and December 1866, 34% recorded parents from the north of England (Durham, Northumberland, Cumberland), 31% from Ireland, 17% from Scotland, 6% from Germany and Norway, 4% from the south of England (London, Devon, Cornwall, Oxfordshire), 3% from Wales, and 5% of parents were born in Australia (Victoria and Tasmania).

Across a broader time span there were many Germans, Prussians and Austrians, as well as Swiss-Italians, like the Quanchi and Perinoni families. Swiss-Italian presence is demonstrated by the manager and shareholders of the Happy-Go-Lucky Gold Mining Company of Piggoreet, whose names at the time their company was registered on 4 January 1865 were Stefano Bolla, Guiseppe Cerini, Guiseppe Danchi, Andrea Danchi, Adami Giovani, Guiseppe Jemini, Antonio Laloli and Gioganni Pozzi. When Guiseppe Jemini died in a cave-in in their tunnel on 16 April 1866 aged 44 years, his friend Alexander Quanchi (whose family had a long association with Piggoreet) gave details that Brugiasco Valley in Switzerland was Guiseppe’s place of birth and that he had been in Victoria since 1854, leaving a wife and eight children behind in Switzerland.[27] The Yung family originated in Darmstadt, Germany, but George Godlip Yung married Christina Wheller in New York, USA where they had two children. By 1863 Amelia Yung was born in Piggoreet and was followed by more to total twelve children.

Travelling from mainly European and British places of origin, couples tended to meet and marry in Melbourne and Ballarat before settling at Piggoreet. For instance, William Atkinson, a 27-year-old miner from Newcastle-on-Tyne in Northumberland married Irish Margaret Lane at Ballarat in 1863 before their second child William was born at Piggoreet, and George William Paul, the German butcher married Louise Shewman from Berlin in 1855 in Ballarat; their fifth child Sybilla was born at Piggoreet in 1866. The towering vertical cliff overlooking the Devil’s Kitchen on the east is still known locally as Paul’s Hill. Many were extended families, with descriptions of informant relationships on birth certificates including uncle, son-in-law, grandfather, aunt, stepson, grandmother and brother-in-law.

One kinship group, from the Alston Moors in Cumberland (now Cumbria), were connected through three sisters, Ann, Mary and Margaret Woodmass who arrived one by one over several years and established their families at Piggoreet. Margaret had married Robert Hodgson, a Cumberland lead miner, at Gretna Green before emigrating in 1856, and they had ten children, four of whom died in childhood. Robert aged eleven and Martin aged nine drowned together in the long swimming hole in the Woady Yaloak creek at Piggoreet near the Golden Horn mine on 21 December 1867. Robert Hodgson was a director of the Atlas Gold Mining Company in the 1860s, and was a member of the jury at an inquiry held on 12 July 1867 after an attempt was made to burn down the Royal Mail Hotel owned by Edward and Maria Hall at Piggoreet. Margaret’s sister Ann Woodmass arrived in Melbourne on the Great Britain in April 1863, aged 28 years, and married John Lee before they also settled with Margaret and Robert Hodgson at Piggoreet, where they had six children over the next decade. The third and youngest sister was Mary Woodmass who was obliged to take the father of her first child, Annie Louisa Woodmass, to court in an affiliation case. Their problems seemed settled by 1871 when they married and continued raising a family.

One grandmother, Jane Forth, who signed as the informant on her grandson Thomas Gardener Beecroft’s birth on 26 December 1865, brought three generations to Piggoreet. Born in 1811 in Rainton, Durham, she was married when only sixteen, and widowed with five children by 1841, the same year that she married Eli Forth, a coal miner from Moorsley in Durham. They then had five children before deciding in 1862 to emigrate. At least four of her married children came with Jane and Eli to Piggoreet, each with families already established, which they then extended. One son-in-law was a stoker, and all had mining experience from the Durham coal fields. Jane herself was midwife to a number of women giving birth in Piggoreet, showing how the Piggoreet community benefited from the skills these northern English brought with them.

There were ten mining companies within easy walking distance of Piggoreet township in the 1860s, including the Try Again which paid £3960 in dividends in the October quarter of 1867.[28] The lease for the Grand Trunk Gold Mining Company just south of the Devil’s Kitchen was taken up at the end of December 1860, and although plagued by problems of flooding proved to be the richest mine on the main lead running north-south from the township. In June 1865 it was ‘yielding magnificently’, regularly paying £20 per original share per fortnight. Its richness and its extent made it one of the best prospects in the Ballarat district, and in its first five years it produced 915lbs (415kg) of gold.[29]

When the Golden Horn Gold Mining Company was formed in December 1862 on the private land of squatter David Clarke, who owned the pre-emptive run of Piggoreet West, an agreement was made to mine on his property for £5000 and 3% of any gold obtained. The first shaft was a quarter of a mile east of Clarke’s Piggoreet West homestead, and its large mullock heap marks the site to this day.[30] This was a lucrative arrangement for Clarke, as the mine yielded over 2000 ounces (56kg) per quarter from the end of 1867 until mid 1871, by which time it had produced a total of more than 1413 lbs (641kg) of gold.[31] The Zuyder Zee Gold Mining Company, abutting Clarke’s run, amalgamated to become the Golden Lake in February 1863, yielding 2425 lbs (1100kg) of gold between 1868 and 1875, and is regarded by Heritage Victoria as ‘possibly the largest deep lead mine site in Victoria’.[32] The Galatea, originally the Scarsdale Extended Company, bought 960 acres from the owner of Moppianimum run in October 1861, thereby bringing the second of the Piggoreet district squatting runs within the influence of the gold industry. The Alchymist Gold Mining Company provided strong employment for local men, but was the furthest from Piggoreet, in the direction of Derwent Jack’s, a long walk to one’s workplace. The Alpha Gold Mining Company was regarded as one of the principal mines in the area in March 1865 when its shares were £175 each, providing a weekly dividend of £5 per share.[33]

Shareholders in these mining companies included many familiar Piggoreet names, showing that it was relatively common to purchase shares in local mines. Many gave their occupation in various records simply as ‘miner’. That they often were shareholders in the very mines in which they worked reveals that good returns could provide a welcome supplement to wages, judging by the mining reports on yields and dividends. There is no hint of agitation or mob behaviour at any period, unlike the southern New South Wales mining district where ‘there was widespread dissatisfaction with the level of earnings at a time when the companies were still seen as very profitable’.[34] At Piggoreet, many were sharing in those very profits. Piggoreet miners earned £2/10/- per week during this boom period when subsistence wages were defined as about 12s 6d a week.[35] Given that the mining companies employed well over 70% of local residents, whether as miners, carters, blacksmiths, stokers, carpenters or engineers, it is clear that the success of the gold mining industry was imperative to the families of Piggoreet in the 1860s. Provision of services for carters, including water carters from the reservoir half a mile to the south-east of the township, the several hotels which provided board and/or lodging to many of the bachelor miners, and work for splitters and carters of wood to the mines, clearly establishes the interdependency of mining companies and townspeople. Mine managers who were community leaders within the town included John Henry Webb, Francis Stephenson, William Maughan, Samuel Maddison and Glaud Pender. Webb, an Irishman who arrived in Australia in 1852, was father of sixteen children from two marriages. He was not only both legal and general manager of the Grand Trunk Gold Mining Company for decades, but took a leading role in the development of educational facilities in Piggoreet and district.

High childhood death rates and unexpected death and injury in the mining industry were realities the Piggoreet families frequently faced. The predominance of Australian-born in death certificates and cemetery records indicates the high death rate of infants and young children. Infant mortality was extremely high, the common causes of death being tuberculosis of the lymph glands of the abdomen or congestion of the brain. Further examples of the realities of death amongst life include that of William Handasyde who was killed in January 1865 at the Try Again mine after being struck by the engine handle.[36] Thomas Blackburn died in the Atlas mine in November 1866 when a large quantity of earth fell on him.[37] A fortnight later a miner named Robert Macksey and his wife Jane went to Piggoreet in the evening to purchase some groceries, but after drinking a nobbler of wine at an hotel Jane fell ill and died at the roadside. Dr Foster had her body conveyed to Coe’s Court Royal Hotel to await the coroner’s arrival, at which evidence was given that she was only 31 years old, with three children, yet her death was due to heart disease.[38] The infant son of Sarah and James Laidler died aged 7 months at Piggoreet, where his father was a miner, from inflammation of the lungs.[39] The Try Again claimed another life when Samuel Brusey was killed by a fall of earth in May 1867 and two men were severely hurt with leg and back injuries.[40] The value of coroner’s inquests is in their ability to reveal something of the daily lives of families, as when 20-year-old Frank Blythman fell from a hundred-feet-high cliff apparently after an apoplectic fit. His mother gave evidence that he had been digging her some parsley at their home in front of Sugarloaf Hill, and that she had dosed him with rhubarb and magnesia when ill. Frank had been a draper, studying to become a school teacher at the time of his death.[41]

Probate and land records show that the mining industry was starting to give way to farming by the early 1870s when the Land Acts legislation began to take effect. Around Piggoreet 45.16% were farmers, while 38.7% still worked in the mining industry, an indication of the economic and industrial change that was taking place following the peak of deep-lead mining in the 1860s and the subsequent working out of the previously rich gold leads. By 1871 the census reveals that there were 78 homes in Piggoreet, housing 278 males and 234 females, a total of 512 inhabitants.[42] The deep-lead companies and the communities supported by them had long been well established by then. With the working out of the alluvial and quartz deep-lead mines about this period, the township gradually became abandoned. The residents moved away and resettled elsewhere in Australia, taking with them the experience, skills and identity gained at Piggoreet.

The community comprised Italians, Germans, Americans, Chinese, Swiss and others besides those from the British Isles, not to mention the currency lads and lasses some of whose parents had experienced penal servitude in neighbouring colonies. They intermarried and had families. Many already had kinship networks, with aunts, cousins and grandparents often acting as informant on birth and death certificates. These families established the social infrastructure they wanted, the schools, court houses, hotels, churches, stores of various kinds, and made use of the links to other communities through various means of transport, predominantly horse-drawn. They made the most of material opportunities as they arose to improve their standard of living, particularly as land legislation of the 1860s and early 1870s was enacted, and later helped them to farm properties where they had earlier sweated underground.

Piggoreet was one of the network of Ballarat’s ‘hinterland’ communities which benefited from a symbiotic relationship with the growing city.[43] Little intensive study has been undertaken into the people living within the goldfield communities that grew during the period of deep-lead companies. Archaeological projects invite ordinary people to be introduced among the artefacts and ruins, the local township histories need families with everyday domestic lives to walk the streets, and the technical mining research appeals for working miners’ personal stories to be told. This limited project, relating to just one town in just one decade and briefly outlined in this paper, will be expanded to embrace the Springdallah goldfields and its populations.

Endnotes

[1] Stirling observer, 9 April 1846, p. 2.

[2] PROV, VA 473 Superintendent, Port Phillip District, VPRS 19/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence (1838–1851), Unit 107, File 48/1393, list of exiles on Anna Maria.

[3] ibid., File 48/1394, list of exiles who distinguished themselves on the voyage.

[4] Geelong advertiser, 4 May 1850, p. 4.

[5] Geelong advertiser, 30 November 1849, p. 2.

[6] James Flett, The History of Gold Discovery in Victoria, The Poppet Head Press, Melbourne, 1970.

[7] WB Withers, The history of Ballarat: from the first pastoral settlement to the present time, FW Niven, Ballarat, 1887, p. 21.

[8] R Broome, Arriving: the Victorians, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon, McMahons Point, New South Wales, 1984, p. 72.

[9] Geelong advertiser and intelligencer, 13 January 1852, p. 2.

[10] Argus, 18 May 1852, p. 2.

[11] Argus, 11 June 1852, p. 2.

[12] Geelong advertiser and intelligencer, 11 August 1852, p. 2.

[13] Argus, 27 August 1852, p. 2.

[14] Argus, 23 July 1864, p. 7.

[15] Argus, 1 November 1853, p. 5.

[16] Star (Ballarat), 7 August 1856, p. 4.

[17] Star, 1 June 1861, p. 3.

[18] Argus, 30 September 1864, p. 5.

[19] ibid.

[20] T Dicker, Dicker’s mining record and guide to the gold mines of Victoria, volume III, Thomas Dicker, Melbourne, 1864, p. 221.

[21] RV Billis and AS Kenyon, Pastoral pioneers of Port Phillip, Stockland Press, Melbourne, 1973, p. 264.

[22] PROV, VA 875 Licensing Court Register, VPRS 4442/P0 Piggoreet Courts (1865–1884), Unit 1.

[23] PROV, VA 2436 Grenville Shire, VPRS 7232/P2 Minute Books, Unit 1, 112.

[24] LJ Blake (ed.), Vision and realisation: a centenary history of state education in Victoria, Education Department of Victoria, Melbourne, 1973, vol. 2, p. 679.

[25] Victoria Government gazette, no. 25, 27 February 1866, p. 477.

[26] W Robertson, History of Piggoreet and Golden Lake, Piggoreet Old Scholars’ Association, Melbourne, 1926, p. 10.

[27] PROV, VA 2889 Registrar-General’s Department, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 173, File 1866/353.

[28] Argus, 11 October 1867, p. 7.

[29] R Supple, ‘Historic gold mining sites in the southern mining divisions of the Ballarat Mining District’, in Report on cultural heritage, Heritage Victoria, Melbourne, 1999, pp. 172–6, see p. 173 (available online athttp://www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/44561/BallaratSouth1to99_1217808893152.pdf, accessed 23 January 2013).

[30] Robertson, History of Piggoreet, p. 6.

[31] Supple, pp. 181–4.

[32] ibid., pp. 187–90, see p. 189.

[33] ibid., p. 165.

[34] B McGowan, ‘Class, hegemony and localism: the southern mining region of New South Wales, 1850–1900’, Labour History, vol. 86, May 2004, pp. 93–113.

[35] ibid., p. 106.

[36] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 153, File 1865/63.

[37] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 180, File 1866/1029; Argus, 15 November 1866, p. 5.

[38] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 185, File 1866/341; Argus, 29 November 1866, p. 4.

[39] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 162, File 1865/995.

[40] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 190, File 1867/388; Argus, 25 May 1867, p. 5.

[41] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 363, File 1877/1013.

[42] AB Watson, Lost and almost forgotten towns of colonial Victoria: a comprehensive analysis of census results for Victoria, 1841–1901, Angus B Watson and Andrew McMillan Art & Design, Blackburn, Victoria, 2003, p. 361.

[43] W Bate, Lucky city: the first generation at Ballarat 1851–1901, Melbourne University Press, 1978.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples