Last updated:

‘The Scots at Springdallah’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 13, 2014. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Jan Croggon and Joan Hunt.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Little physical evidence remains at Springdallah to show for the once-thriving communities that lived and worked there for several decades from the late 1850s. The land that stretches across waterways, cliffs and valleys between Linton and Cape Clear, thirty kilometres south-west of Ballarat, has now reverted to the pastoral landscape that had developed before gold was discovered. Scottish pastoralists created sheep and cattle runs that, after twenty years of idyllic living, were overrun by gold-diggers and their dogs. This paper reveals the nature of the Scots who lived in the Springdallah communities. From pastoralists to mining families, intermarrying and sometimes sharing similar cultural backgrounds, the Scots made an important contribution to the shared community network in this unique and inadequately examined period of Australia’s history.

The settled goldfields of Victoria, birthplace of many townships built on the deep-lead and quartz mining industries of the early 1860s, comprised men, women and children of many nationalities from many countries across the globe. A small number were indigenous to Australia, while more were the offspring of British parentage or had been themselves transported for criminal activities. However, most were free immigrants who arrived from late 1851 onwards to take advantage of the newly discovered goldfields in the midlands and highlands of the new colony of Victoria.[1] Among the many demographic groups were the Scots, within which divisions existed based on religious differences, classes according to wealth, background and education, primary language use, and often whether their native geographical place of origin was in the Highlands or Lowlands of Scotland. A number of historical studies of recent years have highlighted the influence of Scots in the Australian colonies, and this paper adds further evidence of that legacy.[2]

This paper contends that the Scots, from landholding pastoralists to wage-earning miners, made their contribution to, and reaped benefits from, the Springdallah goldfield on the Woady Yaloak Creek south-west of Ballarat in the nineteenth century.

As a case study, it demonstrates the strong presence of Scots in Victoria from pastoral settlement until the establishment of mixed communities in which the Scots often played a leading role. One of the main sources of detailed information enabling recognition of Scottish individuals and families is a database built largely from a comprehensive collection of birth and death certificates (1863–1941) held by a local family, which relate specifically to Springdallah and Piggoreet. They are supplemented by the burial registers and headstone transcriptions from four local cemeteries, and other public records such as vaccination and school registrations, and shareholders’ details from theVictoria Government Gazette. The database provides the statistical analysis quoted in the paper. By combining nominal record linkage with detailed biographical research, a local community study such as this provides strong evidence on which the reconstruction of patterns of the past can be built.[3]The study of Scottish influence in that cluster of small farming and goldfields communities serviced by the townships of Happy Valley and Piggoreet makes clear the impact of the Scots’ emphasis on church and education. That strong community leadership was assumed by Scots is demonstrated by case studies of families such as those of pastoralists Mary Linton, John Browne and David Clarke, professional men like doctor Thomas Foster, and skilled miners like William Ballantine and Glaud Pender. Some families settled for decades and thereby benefitted materially and socially. They passed the economic advantages to the following generations, enriching their descendants’ prospects, often through the acquisition of land as the goldfields declined. Murray raises the importance of the land Acts, especially Section 49 of theLand Act 1869, which had extensive application to the residents at Springdallah. Occupancy by license, eventually leading to freehold grant of their acreage was a sign of success.[4]

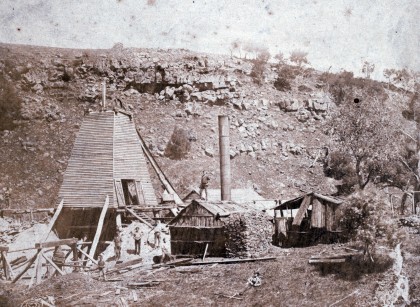

The frenzied gold rush period of shallow alluvial gold discovery had diminished by the later 1850s. From about 1859 the gold industry at Springdallah took on a different and more permanent aspect. Companies were formed to mine the gold embedded deep underground in buried watercourses. Miners and their families were attracted to settle and build townships in the area around the Springdallah Creek. Socially and economically the countryside and its riches impacted on the new and growing population. Conversely, the settlers influenced the network of communities that was made up of native-born Australians, settlers of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish origin, Europeans mainly from Germany and Italy, Americans, and Chinese. These diverse ethnic groups were obliged by circumstances to socialise co-operatively in often challenging situations. Of the total population on the goldfield, many individuals were Scots who brought with them a range of work experience and skill.

However, prior to the settlement of Scottish miners in the early 1860s there were families from Scotland who had settled along the creeks, valleys and cliff-tops of the Springdallah district twenty years earlier, grazing sheep and cattle on tens of thousands of acres for a mere £10 license per annum.[5] Settler pastoralists, popularly called squatters, with their wives and children, were disproportionately represented by the Scots, as ‘at least two-thirds of the pioneer settlers of the Western District were Scottish’.[6] The Scottish diaspora, in a similar pattern to that of other British countries, included Australia among its several places of settlement throughout the world, particularly during the early to mid-nineteenth century.[7] On the one hand there was an element of ‘push’ due to factors such as crop failure and the Highland and Lowland clearances that led to land tenants’ dispossession and eviction to clear land for sheep-grazing, as well as two ‘pull’ factors. One of these was the realisation that the Port Phillip District consisted of vast grasslands, apparently just waiting to be occupied by pastoralists, and the other was created by the later rich discovery of gold to be found across that same area.[8] The breeders of cattle and sheep availed themselves of tens of thousands of acres of land on which to graze their stocks; ‘the young men were set on making their fortunes’.[9]

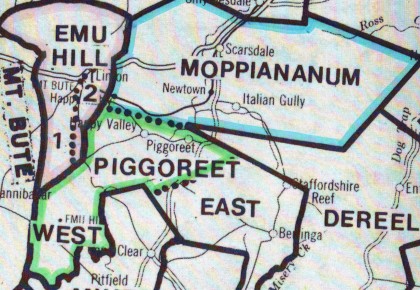

In the country to the north-west of the coastal port of Geelong the Springdallah Creek and its tributaries, eventually flowing into the Woady Yaloak Creek, meandered across parts of three pastoral runs known as Emu Hill, Piggoreet West, and Moppiananum. Kiddle describes the Scottish pastoralists of the Western District as predominantly Lowland farmers.[10] Many were young bachelors, like the brothers Thomas and Somerville Learmonth, cousins William and Archibald Yuille, Henry Anderson, and Francis Ormond junior, who were still in their late teens when they became involved in pastoral pursuits. However, the settlers who occupied the three pastoral stations on which the Springdallah goldfield developed in the early 1850s were atypical. Each of them was over thirty years of age when they took up their runs, two were married with children, and only one was from the Lowlands. Indeed, one of them was a woman, Mary Linton, who applied for the official lease of Emu Hill no. 169 in her own name on 23 February 1848.[11] None of them was a retired army or naval officer as was so often the case during the pastoral pioneering era.[12]

Emu Hill

Joseph Linton was born at Paisley on the Isle of Bute in 1794, and his wife Mary Dunlop was born in the West Indies in 1809, of Scottish parentage.[13] They married in Ayr in June 1827, and departed from Greenock for Hobart on 3 October 1838 on the barque Potentate together with their first three children.[14] After a brief stay, they arrived in Geelong on a coastal steamer in February 1839. They held the Emu Hill pastoral run from towards the end of that year until about 1860, during which time Joseph died (in 1853) and Mary remarried (in 1857).[15] The gold-mining settlements of Dreamers Hill, Old Lucky Womans and Happy Valley came to be established on the 15,000 acre Emu Hill leasehold.

One of the Linton daughters married John Browne of the adjoining run (Moppiananum), and another daughter Jane Allan Linton married Ashton Gartside, a storekeeper at Piggoreet. Yet another daughter Mary Dunlop Linton married Stewart Matthews who took up the Piggoreet East run for some years, and Williamina Dunlop Linton, known as Mina, married an American, Benjamin Hichborne Fernald, the hotelkeeper of the Emu Inn at Pitfield in the 1850s. Three of the daughters married out of the district, but Josephine became the wife of Dryden Phillipson, a mine manager of a mine on Linton station, and it was at Josephine’s home that Mary Linton died aged 78 years.[16] The local marriage networks were strong.

The Reverend John Gow, a Presbyterian minister, had travelled out from Scotland with the Linton family and continued a partnership in the pastoral business while establishing churches throughout his extensive parish, that was known as ‘The Colac’.[17] Born in 1803, Gow was a confirmed bachelor, and committed his time to parish work. He lived in Smythesdale at the time of his death and was buried locally on 22 June 1866, where a fine monument marks his grave in the Smythesdale cemetery. His generous bequest to the Ballarat Hospital signals him as a Scot connected with Springdallah whose contribution was notable.

Moppiananum

John Browne was born on 24 May 1818 at Carleton, Borgue, in the Scottish Lowlands near Dumfries. He was the son of a farming family, his father reporting at the 1851 census that he employed five labourers to work his 328 acres.[18] Browne arrived at Port Phillip in 1840. The 30,000 acre pastoral run of Moppiananum was originally licensed to Captain Charles Henry Ross in 1841, and included present-day Ross Creek. After Ross returned ‘home’ in 1843 it passed into the hands of George Forbes.[19] In early 1850 Forbes transferred the station to John Browne and Thomas Sproat, who was also a Dumfries man.[20] The pastoral run was then estimated to be capable of grazing 1200 head of cattle and 9000 sheep. Browne purchased 960 acres as his pre-emptive right on both the Moppiananum and Piggoreet West runs.[21]

John Browne and Eliza Tennant Linton, who was born in 1829 at Greenock in Renfrewshire and was the daughter of the holders of the adjoining run, were married at Emu Hill on 17 July 1852, and it was they who built the homestead that stood for many years and is today a ruin, viewable from Nimon’s bridge over the Woady Yaloak Creek. After gold was found on his leased and freehold land in 1854 Browne suffered stock losses due to the depredations of diggers’ dogs. This forced him to sell and remove to the Anakies near Geelong. The first three of the seven children of John and Eliza were born at Moppiananum, and the rest at Narada West, Anakie. John Browne is remembered in the Scarsdale area names of Browns and Scarsdale Borough, Brown’s Diggings, Brownsvale and Browns Road.

Piggoreet West

Piggoreet pastoral run, comprising 19,000 acres on the Woady Yallock Creek, adjoined both Emu Hill and Moppiananum. By 1852 when gold was officially discovered at Springdallah the original pastoral run had been divided into two, Piggoreet East and Piggoreet West.[22] On 2 December 1851 Francis Ormond applied for approval for the transfer of ‘Piggereet’ [sic] to John Browne, having held it since 30 March 1850.[23] Ormond and his family had emigrated from Aberdeen to the Port Phillip District in 1842, where his father ran the Settler’s Arms Inn at Shelford before taking up Borriyallock station.[24] Browne then held the lease for about fourteen months, when its pre-emptive sale of one square mile was valued at twenty shillings per acre.[25] The Commissioner for Crown Lands in the Portland Bay District, Henry Hamilton Smythe reported in October 1853 that the existing buildings consisted of a cottage and woolshed, and that there was no indication of auriferous deposit.[26]

David Clarke arrived in Port Phillip from Aberdeenshire in 1840 as a farm servant with his wife Jean, a dairymaid, and their children Helen aged 5 and John aged 3 years.[27] Their ship was the John Bull, the master of which was Captain Francis Ormond. David Clarke managed the Langi Kal Kal station near Beaufort before forming a partnership in Buangor station with Alexander Campbell. By 1855 he had purchased Piggoreet West station, arriving at approximately the same time that the shallow alluvial gold was giving out and men with capital were considering moving in to explore the deep leads.

David Clarke is remembered through his name being incorporated in the parish of Clarkesdale. He provided employment for many part-time gold miners who laboured on his property, allowed his land to be used for picnics for all denominations to fund-raise for their churches, and took a leading role as a committee-man for Piggoreet school and the Presbyterian Church. His son John took over Emu Hill station, and daughter Helen married a local Scottish farming family.

Scottish miners

Rapid industrialisation in Scotland towards the end of the eighteenth century led to the establishment of ironworks, the fuel for which was provided by the associated coal-mining industry. From about 1830 Scotland’s economy increasingly relied on the coal, iron, engineering and shipbuilding industries. Both collieries and ironworks in the Lowlands of Lanarkshire and Ayrshire caused a massive increase in population in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Working the raw materials required a great workforce to mine and manufacture, encouraging waves of migration from Highlands, Lowlands and islands into the new and developing cities of Britain.[28] This movement in turn led to overcrowding and squalor that, especially during times of downturn in the economy, must have made stories of the gold discoveries in Australia, the land of new economic opportunities, seem very attractive. One result was emigration schemes that offered finance, especially after the Emigration Act 1851 (UK) provided even the poorest crofter with financial support to make the life-changing journey for just £1. The process (1852–1857) was overseen by the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society that assisted many poor, mainly single young men, especially from the islands, to emigrate. For many, although circumstances made their migration compulsory, there was an element of choice, especially as the news of greater opportunity in countries like Canada, the United States of America, Australia and New Zealand became widespread.[29] The men from these places brought lead and coal mining skills. The Mining District Reports of 1844–1859 deal with Lanarkshire, the Lothians, Stirlingshire and Fifeshire.[30] Many of the Scottish fathers of children born at Springdallah came from those same counties.

Of the 1108 births registered at Springdallah between 1863 and 1883 there were 177 children born to a total of 76 Scottish fathers, rather neatly balanced by 78 Scottish mothers, but not necessarily married to each other. Sixteen marriages were of Scots who had married in Scotland, arriving with children, and continuing to grow their families at Springdallah, making up about 21% of the total Scottish fathers. A further 33 couples where both partners were Scottish married after arriving in Victoria, a total of 38%. The rest of the total 76 Scottish men who fathered children at Springdallah married in Victoria to Irish, English or Australian-born women, and one Welsh woman. British networks and connections predominated. Where the men had given their occupation as miner on documents prior to being employed by gold mining companies at Springdallah, they were referring to their work experience usually within coal mines and sometimes lead mines, in Scotland. About 65% of all Scottish family men, taking evidence from the birth registrations, worked at Springdallah as miners, rising to 72% when skilled mining positions are included, such as mine manager, engineer, engine driver, blacksmith and carpenter. Some Scots worked in service industries necessary to the maintenance of the goldfield community, such as storekeeper, cobbler, and grocer. Included were the occupations of pastoralist, station overseer, surgeon, and farmer. Some were poor, leaving conditions in Scotland of high unemployment, illiteracy and slum housing. However, ‘… impoverished highland Scots, some of whom spoke only Gaelic … often judged … as jabbering heathens, slow in both body and mind’ were as truly Scottish as were the well-educated, often bi-lingual Presbyterians of high culture and polite society.[31]

A notable Scot upon whom the Springdallah communities relied heavily was Thomas Foster, the local doctor and surgeon who lived at Piggoreet. Thomas was born in Canonbie, not far from Gretna Green in the Scottish borders. He married Mary Ann Brown in 1863 in Melbourne, and they raised their family in a home overlooking the township of Piggoreet, high on the cliff-side road leading to Happy Valley.

Hundreds of Springdallah infants were delivered into the world by Dr Foster, and many residents were attended by him on their deathbeds, including two of his own young daughters.

Another Scot who was prominent at Springdallah was Glaud Storrie Pender, who was born on 27 August 1827 at Whitburn in the Lowlands of West Lothian, where iron and coal mining began in the eighteenth century. He arrived with his wife Grace Muir and young family on the Marco Polo from Liverpool on 28 June 1852, their son William having died from measles on the voyage, during which a total of 52 children died. When living at Scarsdale, Glaud was elected to the first Council of the Municipality of Browns and Scarsdale in August 1862.[32] From early 1862 the family was settled at Springdallah, where the two youngest children were born. Glaud was a director of a number of mining companies, became manager of the Golden Lake Gold Mining Company Pty Ltd, and was President of the Shire of Grenville from 1875 until 1877, around which time he was also a justice of the peace presiding in the Piggoreet court house. His reported presence at many meetings throughout the district over many years is a clear indication of his influence and expertise in the mining industry.

Mining interests increasingly impinged on the local pastoral industry. A local company, formed by its shareholders, reached agreement with David Clarke of Piggoreet West in November 1862 to mine on his private property for the sum of £5,000 and 3% of the gross yield.[33] In May 1860 the Brownsvale Gold Mining Company offered 48 acres of alluvial ground on Brown’s pre-emptive right with £5000 to be invested.[34] By February 1866 the 960 acres that had been John Browne’s run, Moppianimum at Brownsvale, was the freehold of the Scarsdale Great Extended Company, in which year the fenced paddocks were offered for rental for cultivation and grazing purposes.[35] There was constant interaction between the Piggoreet West pastoralist David Clarke and the miners, as when the Golden Horn Gold Mining Company held a ‘baptism of the engines’ ceremony on 7 July 1865, attended by a large crowd including Mr and Mrs Clarke, the proprietors of the property, who were toasted and thanked. In December of the same year, despite his being a Presbyterian, David Clarke made available his ‘picnic paddock’ for a Church of England tea meeting that was largely attended.

The network of Scottish families who depended upon and assisted one another is illustrated by the Ballantines and Mortons. William Ballantine, born at Auchinleck in Ayrshire in 1831, arrived in Victoria with his brother James in January 1854. On 5 August 1859 William and Euphemia Moore Morton, also born in Auchinleck in 1842, were married at her father’s house at Smythesdale by the Scottish Presbyterian minister, Reverend John Gow. James and his wife Isabella moved back and forth between Springdallah, Smythesdale and Bendigo between 1856 and the mid 1870s. The extended Morton family settled in the district where in 1870 Euphemia’s father had taken up land under section 42 of the Land Act 1869 near Brownsvale. Of the eleven children born to William and Euphemia, the first four died within three months in 1868 from diphtheria. Eight children were born at Golden Lake before the family moved to Waterloo near Beaufort. William Ballantine was at various periods a miner, engine-driver, and storekeeper at Golden Lake on a purchased allotment.[36] His brother James Ballantine is also described as an engine-driver, when living and working in Bendigo.

Their birthplace of Auchinleck near Cumnock had been involved in quarrying and deep pit mining from the 1830s, and iron companies had provided employment for the people of the area, so the engine-driver training received by William and James Ballantine may have been associated with that local employment. Their experience would have made a valuable contribution at Springdallah. The network of extended family connections was strengthened through the marriage of Euphemia’s sister Mary Morton, who in 1859 married George Peace Sinclair from Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands, and lived in the Springdallah area on and off for more than two decades. Sinclair was the mining manager of the Golden Belt Gold Mining Company.

William Clarkson was a miner from the rich coal and ironstone mining area of Wilsontown, Carnwarth in Lanarkshire where a huge iron foundry started in 1795. By 1842 both the foundry and coal mine had ceased, so when Australia’s gold-mining opportunities arose Clarkson, his parents, and his brothers and sisters all emigrated. He married Janet Gow from Coupar Angus in Forfarshire in 1852 at Bothwell in Lanarkshire, and by the mid 1850s the extended family established themselves on the Woady Yaloak goldfields.

Henry Dobbie was born in Perth, Perthshire in 1839 and married Mary McLaurin from Monkland, Lanarkshire in about 1842. They married on 30 September 1862 at Scarsdale and had several children, before Henry died in 1875 after being injured in a fall of earth in the Golden Lake mine. These Scottish families would have been either members of the Presbyterian Church or, less commonly, the Catholic Church. The early establishment of the Presbyterian Church at Piggoreet signifies the influence of the Scottish population, as there were no Catholic, Wesleyan or Lutheran churches there despite members of those religions being well represented in the community. David Clarke of Piggoreet West gave strong support to the local Presbyterian church.

The Cameron family exemplify very well the experiences and background of the Scots who mined the deep-lead mines at Springdallah. Born about 1802 near Glengarry in Invernesshire, Ewen Cameron married Ann McDonnell in 1833. They started their married life in the Kilmonivaig parish near Fort Augustus, Invernesshire, where Ewen was a stonemason. The Camerons embarked with seven children aged from seventeen years to seventeen months, on board the Chance that departed from Liverpool on her maiden voyage on 24 July 1852. The family were Catholic, and it seems likely that they spoke both Gaelic and English, and the parents could neither read nor write. By December 1861 at least, they were living at Lucky Womans Diggings, where Ewen was a juryman at an inquest into the drowning death of a young boy who had been swimming in a dam.[37] The family was well settled, and possibly financially secure, by December 1864, when Ewen purchased twelve shares valued at five pounds each in the Young Australia Gold Mining Company at Bulldog (later known as Illabarook).[38] Their 24-year-old daughter Ann had married a local man James Honan in 1862, then the eldest daughter, Mary, married Owen Sullivan who also lived locally. Their son Ewen married the daughter of a local Scottish family, Mary McGruer after he had applied for 20 acres of land in the bordering parish of Mannibadar in July 1866, under license in accordance with section 42 of the Land Act 1869. Ewen and Mary then had a family of seven children born locally, but took up land near Charlton after 1877, after the Victorian Government had the Wimmera surveyed and thrown open for selection.

In the meantime, Ewen senior was appointed the herdsman to the Argyle and Linton Farmer’s Common in September 1865, when he would have been about 63 years old, and possibly no longer wanting to do heavy work mining underground.[39] In September 1867 Ewen senior, giving his occupation as farmer, applied for a license to hold 14 acres at Lucky Womans on the site of the now worked-out Try Again gold mine, having gained written permission of the remaining shareholders, who indicated that the mine was finished.[40]

Ewen purchased that allotment in December 1871, and held a further 12 acres by May 1872. However, he died on New Year’s Day of 1876. His death was registered at Happy Valley, and his body was interred in the Linton cemetery. He bequeathed his real and personal property, amounting to £375/-/-, to his wife Annie and son Lewis, being more than 32 acres in the parish of Argyle, with 26 head of cattle, 40 acres in the parish of Mortchup, and 246 acres in the parish of Wycheproof, with cattle, the estate to be administered by his sons Lewis and Duncan Cameron of Linton.[41] Ewen and Ann Cameron appear to have raised their socio-economic status by coming to Australia, their earlier years in Scotland having borne the hallmarks of poverty and disadvantage, exemplified by their lack of education, a state overcome by their children. The correspondence in their land files clearly show that their children had attended school, most likely at Lucky Womans School no. 376, and all of them in adulthood became very well established on large properties in the Wimmera.

This paper provides clear evidence of the success with which Scots adapted well to the Springdallah district, settling as pastoralists in the pre-gold period, and working in the thriving gold-mining industry throughout the nineteenth century.[42] Broome comments that Scottish consciousness in the colony generally seemed to be weak, yet at Springdallah, at least, a Scottish narrative is apparent.[43] The Scots did make their presence felt at Springdallah when that goldfield was at its zenith, although the Scots at Ballarat endowed a more tangible and lasting legacy there, through statuary and establishment of institutions in the goldfield that became a city.[44] The Springdallah Scots made a grass-roots contribution, because they appear strongly at all levels of the community. The communities of Springdallah, with Scots well represented on the local school committees, supported and encouraged the movement towards universal education that resulted in four schools being built on the goldfields there, at Piggoreet, Happy Valley, Golden Lake, and Grand Trunk. Ample evidence survives of interactions and mutual support being shared by farmers and miners alike, through commercial, shareholding, educational and religious endeavours. The strength of the Presbyterian Church in the Springdallah community was no doubt a source of comfort and strength to the Scots there, and assisted in their apparently easy adaptation to a new life.[45] Their numbers were not great compared with the Irish and English, but their presence was certainly felt. The opportunities for mutual benefit on the goldfields of Springdallah were not missed by the Scottish families enjoying relatively full employment and social improvement. They made a new life for themselves and their families in their adopted home, and in the process both Springdallah and they prospered.

Endnotes

[1] Geoffrey Serle, The Golden Age, a history of the Colony of Victoria, 1851–1861, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1960, p. 383.

[2] Malcolm D Prentis, The Scots in Australia, A Study of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, 1788–1900, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1983; Jane Beer, ‘Land and Inheritance’, in Colonial Frontiers and Family Fortunes – Two studies of Rural and Urban Victoria, Jane Beer et al. (eds), University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 1989; Don Watson, Caledonia Australis, Scottish Highlanders on the frontier of Australia, Random House, Sydney, 1997; and the works of historians such as Eric Richards, Marjory Harper, Tom Devine, Jan Croggon, are important in this regard.

[3] Leigh SL Beaton, ‘Westralian Scots: Scottish Settlement and Identity in Western Australia, arrivals 1829–1850’, PhD thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, 2004.

[4] Michael J Murray, ‘Prayers and Pastures: Moidart emigrants in Victoria, 1852–1920’, PhD thesis, Deakin University, Geelong, 2006, p. 247.

[5] Tony Dingle, Settling: The Victorians, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, McMahons Point, NSW, 1984, p. 25.

[6] Margaret Kiddle, Men of Yesterday: A Social History of the Western District of Victoria 1834–1890, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1967, p. 14.

[7] Marjory Harper, ‘Opportunity and Exile: Snapshots of Scottish Emigration to Australia’, Australian Studies, vol. 2, 2010, p. 2, available at <www.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/australian-studies/issue/view/149>, accessed 12 April 2014.

[8] Serle, The Golden Age, p. 32.

[9] Kiddle, Men of Yesterday, p. 40.

[10] ibid., p. 14.

[11] PROV, VPRS 5920/P1 Pastoral Run Files [Microfiche Copy of VPRS 5359], no. 396, Emu Hill, microfiche 348 and 349, no. 48/790, 29 March 1848.

[12] Marjory Harper, ‘Opportunity and Exile’.

[13] Jillian Wheeler, ‘Who Owns Linton’s Past? Multiple histories in a Victorian goldfields town’, PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 31, 49.

[14] Ralph V Billis and Arthur S Kenyon, Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip, Stockland Press, Melbourne, 1974 (first edition 1932), pp. 204, 245, 264.

[15] ibid., p. 97.

[16] Wheeler, ‘Who Owns Linton’s Past?’, p. 50.

[17] The Daily News, Perth, WA, 23 July 1932, p. 4.

[18] Census of Scotland, 30 March 1851, CSSCT1851-211, ED4.

[19] Geelong Advertiser, 29 April 1848, p. 4.

[20] Geelong Advertiser, 4 February 1850, p. 2.

[21] Joan E Hunt, Forest and Field: a history of Ross Creek 1840–1990, Jim Crow Press, Ballarat, 1990, pp. 7–10.

[22] Billis and Kenyon, Pastoral Pioneers, p. 264.

[23] PROV, VPRS 5920/P1, no. 51/832, 2 December 1851.

[24] Alexia Howe, ‘These People … Give the prevalent Tone to Society’ in That Land of Exiles: Scots in Australia, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Edinburgh, 1988, p. 109.

[25] PROV, VPRS 5920/P1, no. 209/55, 19 January 1855.

[26] PROV, VPRS 5920/P1, document dated 13 October 1853.

[27] Grenville Standard, 21 December 1918, p. 4.

[28] Andy Potts, ‘The Lanarkshire Mining Industry: History of Mining’, available at <http://www.sorbie.net/lanarkshire_mining_industry.htm>, accessed 15 March 2014.

[29] Tom Devine, ‘Migration and Empire, The Migration of Scots’, available at <http://www.educationscotland.gov. uk/video/n/video_tcm4567283.asp>, accessed 15 March 2014.

[30] Scottish Mining Website, available at <http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/64.html>, accessed 25 March 2014. The Mining District Reports were annual reports produced by Hugh Seymour Tremenheere, who was appointed a commissioner to inquire into the operation of the Mines and Collieries Act 1842 and into the state of the population in the mining districts. He produced fifteen reports between 1844 and 1858. The website cited above provides a précis of each report.

[31] Richard Broome, Arriving: The Victorians, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, McMahons Point, NSW, 1984, p. 64.

[32] Patrick McGrath, ‘The Story of Browns and Scarsdale’, Sands & McDougall Directory, Sands & McDougall Ltd, Melbourne, 1912, p. 73.

[33] Star, 21 November 1862, p. 4.

[34] Star, 11 May 1860, p. 2.

[35] Ballarat Star, 26 February 1866, p. 4.

[36] PROV, VPRS 439/P0 Applications for Gold Mining Leases [Inglewood Division Mining Registrar], unit 86, file 2452/49, 10 July 1871.

[37] PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, unit 103, file 1050, 15 December 1861.

[38] Marion McAdie, Mining Shareholders Index 1857–1886, CD database, Marion McAdie, Ararat, 2006.

[39] Ballarat Star, 26 September 1865, p. 3.

[40] PROV, VPRS 627/P0 Land Selection Files, Section 31 Land Act 1869, unit 57, file 5562/31.

[41] PROV, VPRS 7591/P2 Wills, unit 24, file 14/253; VPRS 28/P2 Probate and Administration FIles, unit 46, file 14/253.

[42] PROV, VPRS 640/P0 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, unit 629, file 1065; VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, unit 2039, file 726.

[43] Broome, Arriving, p. 105.

[44] Jan Croggon, ‘The Scottish in Ballarat 1851–1901: Pathway to Cultural Convergence’, delivered at University of Melbourne Department of History conference August 2006, Us and Them: perceptions, depictions and descriptions of Celts, p. 1.

[45] Prentis, The Scots in Australia, p. 253.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples