Last updated:

‘Giving Birth in the Bush: Colonial women of Victoria and the challenges of childbirth, 1850–1880 ’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 17, 2019. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Janine Callanan.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article explores the common and unique challenges of early maternity which young migrant women faced in colonial Victoria. The private nature of pregnancy and childbirth in this era means that there are very few recorded personal accounts of their experiences. Using a range of primary sources which provide facts and clues and applying these to contemporary understandings to build a potential narrative of nineteenth-century childbirth in rural Victoria, this article provides insight into a fundamental female experience of colonial life.

Locating the personal in public records

Much of the existing Australian research on the early stages of maternity among young migrant women in Colonial Victoria has primarily focused on the history of nursing, midwifery and obstetrics. The individual experience of women giving birth has been largely overlooked. This article seeks to describe the physical, practical and emotional challenges which childbearing entailed, so far from the comforts and supports of family, often in places remote from village or town life, and the impact of the harsh physical environment on non-Aboriginal childbearing women. It considers birth in the context of personal history, available resources and prevailing culture, and explores ways in which some colonial women of rural Victoria managed the challenges they faced in their ‘confinement’.

Pivotal to this study is the use of the Victorian coronial inquest reports, previously utilised in research to illuminate the tensions between nineteenth-century medical practitioners but which also have tremendous value in their capacity to provide description and voice to the birth experiences of pioneer women in Victoria, and thus in re-constructing personal experiences of childbirth. For this research, a small sample of twelve coronial investigations were consulted, from rural locations around Victoria. These exhibited some common elements. In most of the events documented in these reports, both a doctor and a midwife or nurse attended the woman, however anecdotal and documentary evidence indicates that for the vast majority of rural births in nineteenth-century colonial Australia,[1] it was primarily a midwife, a nurse or a ‘handywoman’ who was engaged to provide support. Amongst poorer communities, a medical man[2] would be called upon if available, only when serious complications arose. In each of the inquest files consulted, witness depositions were included from a qualified doctor, a midwife or an experienced attendant, and a friend or spouse.

Certainly, the great majority of births in pioneer Victoria were successful for mother and child. Even in the absence of first-hand accounts, this article aims to demonstrate the potential to build a picture of individual women’s experiences of childbirth and early maternity, using a range of public records and historical sources. There has been growing interest over recent years in the pioneering women of Australia. Scholars such as Clare Wright, Marjorie Theobald and Patricia Grimshaw have examined aspects of migrant women’s experience in the nineteenth century and identified significant female agency within Australian colonial history, revealing the wider impact of choices pioneer women made in their domestic and social lives.[3]

A great many young women chose to leave behind the promise of lifelong drudgery, others turned their backs on the rigidity of Victorian life in Britain.[4] For most of the thousands of Irish migrants, coming from a country decimated by starvation, destitution and disease that held few prospects, emigration was their only alternative. For all these reasons and more, by the 1850s women arrived in their thousands, from England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales and elsewhere, seeking husbands and riches on the goldfields of Victoria, or security and good health in a land of promise and abundance. Life in early Victoria, however, was far from easy and rarely comfortable. While most migrant women were intent on a different kind of life to the one they had known, the inescapable task facing nineteenth-century women, particularly in a new colony, was to create a stable domestic family life, and thus a more ‘civilised society’, by producing children.[5]

Despite the extraordinary distance from birthplace, family and culture, these women essentially belonged to the Victorian era, with its gender constraints and expectations. Childbirth discussion belonged in the private domain only, and the subject of pregnancy and birth was not publicly spoken about, except in the most discreet, indirect manner. A woman’s late pregnancy, labour and post-natal period was described euphemistically as her ‘confinement’ and even those who were highly literate did not provide much written detail about this time, particularly in regards to the process of birth itself.[6]

Surviving diaries from this era were generally penned by more affluent women.[7] This article is focused on the far greater number of working-class women, many of whom were semi-literate and time poor. Self-reflective journals were generally not part of their daily grind, and although many men and women exchanged letters with loved ones in their native countries (in an excruciatingly-slow process by today’s standards), relatively few of these have survived across so many generations.[8] There is an additional impediment to gaining direct insight into nineteenth-century experiences of childbirth, in that while issues of decorum lent a secrecy to the realities of maternity, the ordinariness of childbirth also rendered mothers’ voices mute.[9] So much about the lives of these women was new, different and challenging, while the trials of childbearing were simply a woman’s lot in life; something to be endured.

However, there are several contemporary resources at hand which offer facts and clues to nineteenth-century labour and birth. Some diaries and letters do survive: one important example is the diary of Sarah Davenport, a semi-literate English migrant, who settled in the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, and wrote her reminiscences in later years, including memories of her grief at her young son’s ship-board death, her consequent miscarriage, and the birth of her child in Victoria.[10] Government documents and statistics, civil registrations, immigration records, newspaper reports and advertisements provide facts. Inquest depositions provide voice and detail. Records of local history, such as local council meetings and research of town planning and development, describe domestic arrangements such as housing and access to water, and trace the development of rural communities, including health services. Family histories provide further context and life detail. A combination of these sources can be used to provide insights into the practical, social and physical factors which played a role in each woman’s childbirth story.

This article does not attempt to describe the essential birth experience for pioneer women, for certainly there is no such thing. Instead, following the lives of several young women, it aims to demonstrate how the utilisation and analysis of publicly-held records and reports can illuminate the physical circumstances in which this sample of colonial women lived, to gather together the fragments of fact and contemporary description which suggest both common and conflicting experiences of colonial maternity. In the spirit of ‘history from below’, this endeavour to reveal the daily life of ordinary people must be fuelled by details often ignored in histories which pursue ‘the big picture’ of nation building and momentous events.[11] In addition, family history is both enriched by the exploration of these records and provides valuable personal records which contribute to the construction of narratives. Thus, exploration of contemporary government records such as inquest reports may lead to the construction of individual and localised experiences and contribute to a more thorough understanding of colonial family life. Factual details of one woman’s experience do not constitute evidence for another, but when applied to similar circumstances they are valuable, indicating how her labour and birth may have unfolded, and the challenges which other pioneer families may have also encountered.

Childbirth: a dangerous activity

Even with medical and family support, things often went wrong during and shortly after childbirth and there was a chance that mother, infant, or both, would not survive the event. Research by Janet McCalman and Madonna Grehan into the medical challenges and conflicts of nineteenth-century Australian obstetrics paint a stark image of jeopardy and suffering faced by so many young women in childbirth.[12] The most common difficulties faced in labour during the nineteenth century were described as infection, fever and convulsions, uterine rupture, placenta praevia (when the placenta is positioned across the cervix), retained placenta and blood loss.[13] Statistics of maternal death from abortion during this period are unclear, as death was often disguised as fever or blood loss.[14] In addition, many women in this era suffered from poor health, or had been subject to disease and malnutrition in their youth, which compromised both infant and maternal health.[15] Rickets, for example, was rampant in the industrial centres across Europe during the nineteenth century, where the urban poor saw little sunshine and ate a poor diet.[16] The disease impacted skeletal growth and development, and ultimately reduced the strength of women’s pelvic bones, causing obvious complications in the natural process of birth.[17]

Likewise, famine and disease in Ireland throughout the 1840s and 50s meant that many Irish-born women in Victoria carried long-term physical issues which impacted their capacity to survive a difficult pregnancy or childbirth. McCalman claims that ‘Pregnancy could be a death sentence’. Her research into women’s health in early Victoria found that in 1860, one in fifteen pregnant Irish-born women who presented at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne had a ‘contracted or deformed pelvis’ and had been children during the Famine.[18]

The danger was not over upon delivery of an infant. Infection following childbirth, or ‘child bed fever’, often claimed the life of a mother in the days after childbirth, and McCalman reports that infant mortality rates in colonial Melbourne fluctuated between 4 and 11 per cent. Her research draws on patient records from the establishment of the early Royal Women’s Hospital in the 1850s, and finds that maternal death rates were around 4.5 per cent of births at the hospital between 1856 and 1874, while Wright suggests that these figures were likely to be much higher in the goldfields, where medical support was not available and clean water scarce.[19] In her article outlining the history of childbirth in Sydney, Featherstone points out that maternal nutrition also played a key role in successful labour, as illustrated by the very high levels of complication in births at the city’s Benevolent Society.[20]

Coronial inquest reports: narratives of family tragedy

At a time when doctors and midwives were often in tense conflict and competition over the arena of birth, the death of a woman or her baby was regularly subjected to a coronial investigation.[21] Grehan provides fascinating examination and discussion of the role and standing of midwives in colonial Victoria, and describes the often tense relationship these women had with medical men who served the same localities. As doctors generally charged more for their services, they were often called to assist only when a woman’s labour became complicated, or in case of post-natal emergencies.[22] Glenda Strachan contends that this was also reflective of a preference for women as attendants, due to tradition and a sense of delicacy.[23] Midwives were often unqualified, although a great many were highly experienced; in the event that mother or newborn died during or after birth, it was not uncommon for one medical attendant to declare medical or criminal negligence by the other.[24] In such cases, a coronial investigation was held, to identify cause of death and responsibility. At the root of this tension was the growing medicalisation of childbirth, which McCalman proposes partly arose from the introduction of obstetric instruments such as forceps, and which led to the popular negative characterisation of midwives, despite them often having strong community support.[25]

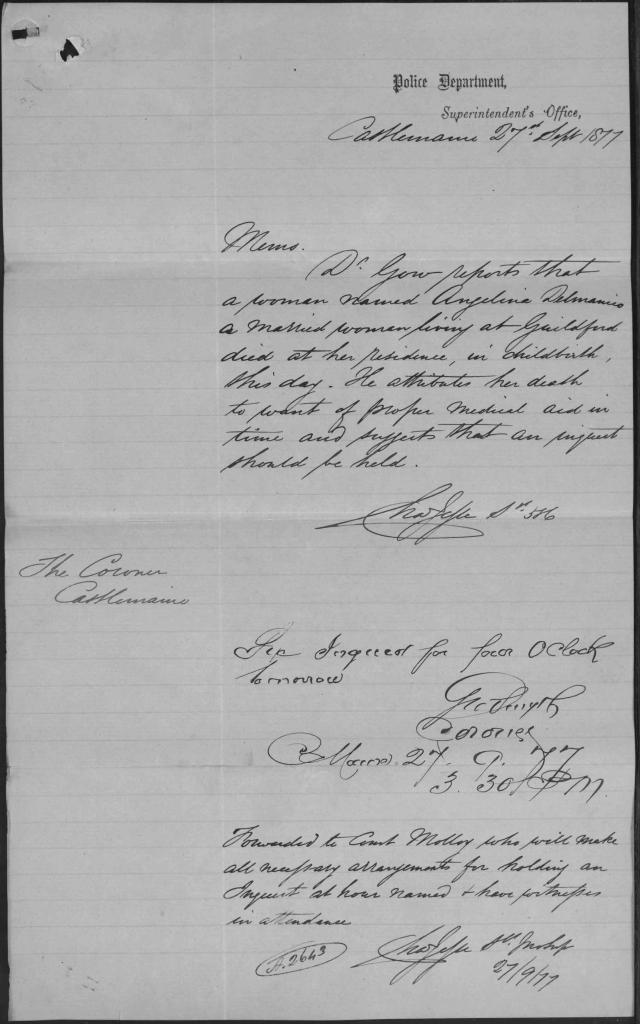

Police report from inquest into the death of Angelina and unnamed child Delmenico, PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 368, Item 1877/307.

It is a consequence of this professional tension, and subsequent legal processes, that we now have open access to a greater number of detailed contemporary descriptions of each of these childbirth events, providing powerful insight into the realities of social, domestic and medical conditions in nineteenth-century Victoria. The described experience of one family’s tragedy may provide clues to shared experiences within a community, regarding available resources and impediments to safe childbirth, and to the choices and accepted practices of labouring women and their attendants. For family historians, these inquest reports provide an intimate window into the domestic lives of colonial ancestors as few other records can do.

Coronial inquests were generally held in the days immediately after death, when witnesses made detailed statements, often describing the circumstances of the event and the actions of each person involved. Husbands, midwives, medical men, neighbours and other family members described the progress of the woman’s labour, the help at hand, the presence of others, what the woman said, how she looked, and provided detail about physical and medical challenges which had combined to create disaster. Panic, despair, hopelessness, grief, anger, frustration and fear – these sentiments are each apparent in the witness statements of a birth gone tragically wrong. In this way, inquest documents provide valuable insight into the personal experience of childbirth and give voice to early Victorian settlers who are otherwise silent.

Grehan’s paper, ‘A most difficult and protracted labour case’, uses the 1869 inquiry into the death of Mrs Margaret Bardon as a case study to discuss the professional tensions which existed between medical men and midwives.[26] This same inquiry also provides useful clues to Margaret Bardon’s personal experience, by describing such details as her pain relief, in the form of opium and brandy, and her previous confinements, as described by her husband, John.

The deceased has had five children before this last. The first is still born and all the others are alive still. The deceased’s last child was born alive without medical assistance. She was in labour for only three quarters of an hour on that occasion and was delivered of a full grown healthy male child which is alive still. She had medical attendance for the second, third and fourth children, and in the delivery of the fourth and fifth, no instruments were used.[27]

Indeed, when we read that Mrs Bardon cried out ‘in a very loud voice’, ‘Look here, I am done for’ upon seeing the ‘dirty white’ state of her amniotic fluid, it is easy to sense the couple’s growing panic.[28]

Like the Bardon case, the following examples demonstrate how coronial inquest witness statements are valuable in illuminating the personal experience of labour, and particularly in combination with newspaper reports and local histories, fuel our understanding of childbirth experiences in a rural context through the mid-nineteenth century.

Such intimate first-hand accounts of a fundamental function in domestic family life, provide social and family historians with a closer understanding of the personal and community challenges which precipitated change. Clare Wright’s comprehensive research into the participation and influence of women in the Eureka Stockade event is notable in its attention to the domestic and social activity of Ballarat women whose responsibilities as mothers, wives, sisters and daughters, were key motivating factors for political activity.[29] The story of colonial Victoria is expanded beyond the traditional masculine narrative when we give attention to the experiences of domesticity and family and integrate these with broader social and cultural histories.

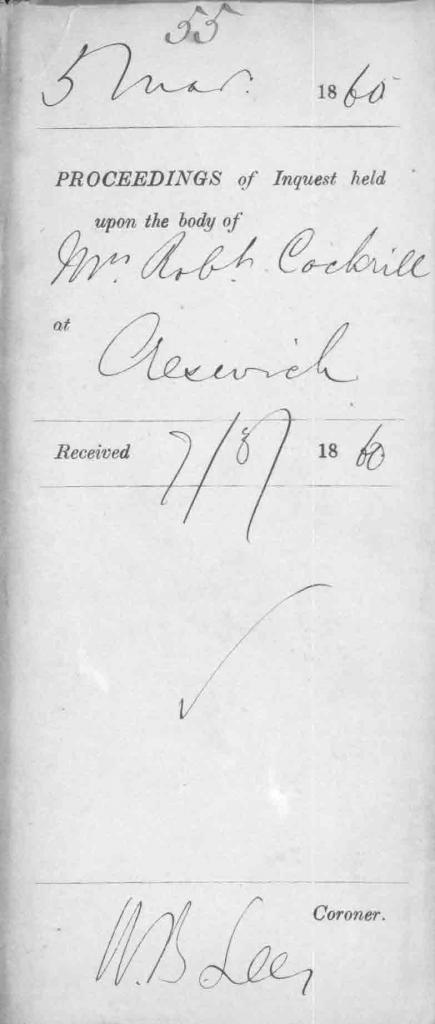

Inquest into the death of Mrs Robert Cockrill, PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 90, Item 1860/55 Female.

Several witnesses were called to give their version of the events in 1860 leading to Susan Cockerill’s death from haemorrhage, soon after delivery of her eleventh baby in the goldmining township of Creswick. Mrs Cockerill went into sudden and intense labour at 1.00 am and sent her husband to collect the untrained nurse she had earlier engaged. The nurse, Luisa Buckley was a married woman with seven children of her own and expected to be paid for her services. Buckley lived ‘about a half mile’ from the Cockerill home and came immediately. In the meantime, Mrs Cockerill had also sent her teenage daughter to a neighbour’s tent for immediate assistance.[30] The neighbour was Ann Whalley, who declared in her statement that she ‘knew little about it’ (childbirth), although she knew enough to recognise that there was ‘no more bleeding than was usual’. The baby arrived before any of these people had returned to the family tent, and Susan Cockerill asked her friend Ann, to ‘move the baby, that she might be more comfortable … The cord was twice round the child’s neck. I put it right, and just then Mrs Buckley arrived and took charge of her care.’[31] Luisa Buckley ‘took the child to dress it and put it by, then spoke to the deceased and asked her how she was. [Mrs Cockerill] said she was rather weak and had felt so since her confinement.’ Together, the women attempted to give her some warm tea, but she refused it. Her husband had better luck, feeding her ‘a little gin and water’, followed by some tea. The nurse finished dressing the infant before attending to Mrs Cockerill, when she discovered that the afterbirth would not ‘come away’.[32] The witness statements of both women tell us that they waited for at least a couple of hours before the nurse decided that too much time had passed, and a doctor was fetched by Robert Cockerill. After his examination, Doctor Hasten applied a napkin which he asked the nurse to check frequently for ‘flooding’. Susan Cockerill’s hands and feet were very cold. She asked her husband to keep rubbing her cold legs, and Mrs Buckley applied ‘hot water cloths’ to her feet. Attempts to assist the placenta to come away from the uterus included holding the woman over a pot of hot water, which took the efforts of all three attendants and remained unsuccessful. The use of instruments was not suggested. The doctor advised Mrs Buckley to administer a teaspoon of brandy every ten minutes. Although her pain was described as ‘excessive’ and caused her to keep passing out, there was no other pain relief on hand. The doctor left after forty-five minutes to ‘get medicine’, but we are not told what this medicine may have been and Mrs Cockerill had died before he returned.[33] The medicine the doctor sought was possibly some form of pain relief, such as opium, as he had already advised Luisa Buckley that her patient would not survive.

Robert Cockerill’s statement tells us that his wife ‘always had easy labours and never had a doctor’.[34] We do not learn very much about their living arrangements, except that there were at least two rooms in the tent, most likely separated by a canvas sheet, and presumably more, as this was a large family. There is no mention of any children other than the teenage daughter, but as the labour came on so quickly, and had been straightforward in the past, it is possible that some of the other Cockerill children were present in the tent, and witnessed their mother’s pain. Robert Cockerill spoke of sitting on a box by his wife, which indicates rudimentary furnishings, and moving away to wait in the ‘other room’, from where he could hear disaster unfolding. His statement conveys the helplessness he felt witnessing his wife’s pain and not knowing how it could be best alleviated, and ultimately his grief when he realised his wife had died.[35]

Overall, alcohol played a prominent role in pain management across each of the births investigated. In some coronial inquiries, including Mrs Cockrill’s, witnesses were asked about the alcohol consumption of the female attendants, although in none of the investigations was the doctor’s sobriety questioned. This is reflective of the dominant attitude of both the medical profession and the press towards untrained midwives, and their frequent characterisation as ignorant, drunken women.[36]

Martha Lithgow of Yering suffered a similar fate in 1864. Her attendant, Mrs Gordon, described herself as having ‘been accustomed to attending women in their labours’ but added that ‘I attended her as a neighbour’ and had not asked for payment. Strahan’s research of birth attendants in rural New South Wales at this time found that about half the women in her sample were attended to by female neighbours or family members, in an unpaid and often reciprocal arrangement.[37] Mrs Gordon had tried to bring away the afterbirth ‘but I did not use much force’, she said. For her state of weakness, Mrs Lithgow was fed a thin gruel, and ‘a few spoonfuls of sherry for the pain’.[38] Grehan’s research tells us that the ‘worst examples of midwifery practice have been preserved for posterity’, including the crushing of infant heads and breaking of bones, the pressing of body weight on the abdomen to hasten birth, forcible dilation of the cervix and pre-emptive slicing of delicate pelvic tissue. Contemporary newspaper reports indicate that doctors too could be rough in their examinations and when undertaking the manual removal of afterbirth. One self-styled medical man on the goldfields was charged with manslaughter in 1859, after he severed the infant’s arm using crude forceps. Included in his bag of instruments were scissors, needles, bodkins and a pair of tooth forceps. For his services, he demanded £5.[39] McCalman’s research of obstetric and maternal health at the new Melbourne Lying-in Hospital describes both the female misery and medical advances taking place at this time. However, in the overcrowded shanty towns around Victoria, there was an absence of many medical options and modern equipment, and with a lack of real obstetric knowledge, birth attendants were not well equipped to manage serious birth complications, even when they were fully ‘qualified’, rendering the woman and her infant hopelessly vulnerable.[40]

In 1856, seventeen-year-old Fanny Treadwell was the young wife of a blacksmith in Muckleford, ‘said to have possessed uncommon personal attractions’. Muckleford had in 1852 become a ‘rush’, and quickly attracted up to four thousand hopeful miners.[41] Contemporary descriptions indicate that at the time of Mrs Treadwell’s confinement, the locality was still heavily wooded, with just a small grassed clearing cut through the very dry forest.[42]

Fanny Treadwell’s husband and her mother were present when she became ill in the late stage of her first pregnancy.[43] Arrangements had been made for a midwife, but when she could not attend, she recommended another.[44] The midwife attending the birth, Mrs Lawson, declared that she ‘had midwifery qualifications from Glasgow’ and explained that she had ‘left the certificates in Adelaide’.[45] Fanny Treadwell delivered her infant daughter safely, but her condition deteriorated a couple of days afterwards. To combat the shivering, Mrs Treadwell’s mother wrapped her up, and gave her a little brandy. Mrs Lawson declared that everything was fine, and bathed her patient’s head and breasts in vinegar and cold water ‘to allay the inflammation’.[46]

A doctor was eventually fetched by the husband, and diagnosed inflammation of the bowels – a common symptom of dysentery, a disease which swept through Victorian goldmining communities in the 1850s and 60s.[47] Dr WF Preshaw described himself as a ‘duly qualified medical practitioner, residing at Castlemaine’, about seven kilometres from Muckleford, a distance which may have taken at least an hour by buggy, over poor roads.[48]

Diseases were rife around the central Victorian goldfields. This was in part because medical knowledge was thin on the ground, and many unqualified men treated local families with various brews and concoctions. Often these were simply unhelpful, others were quite poisonous. Drinking water was shared for all purposes and often contained human effluent.[49] Without clean water for drinking and washing, childbirth became a much more dangerous event, and many women and new infants died quickly in this region. When young Mrs Treadwell died six days after giving birth, the coroner’s finding was that ‘natural causes’ were to blame. Her infant daughter died two months later, as was often the way.[50]

Thirty-three-year-old Angelina Delmenico gave birth to her sixth child in Guildford, near Castlemaine, in 1877. Her husband, Giovanni was away at the land selections and so her sister-in-law (with whom she had journeyed from Switzerland ten years earlier) slept with her for four weeks before she went into labour. ‘I assisted her in the night time, looking after the children, so as not to disturb her rest’. When Mrs Delmenico’s labour pains began she had said ‘I am all wet and you had better go for Mrs McHeeny’, and her sister-in-law ‘got this lady to stay with her, then went for the nurse lender – she came in less than half an hour’.[51] Mrs McHeeny, declared in her statement that she had only been present at a couple of other births before, when she was ‘called upon suddenly’. It became clear that the infant was presenting as breech as ‘one hand was protruding from the womb’, so Mrs McHeeny sent for Mrs Goss, a more experienced woman who had attended four of Mrs Delmenico’s previous confinements.[52]

Guildford at this time was much less populated than during the goldrush of the 1850s and 60s.[53] Clearly, however, there were several people who Mrs Delmenino could have chosen as a birth attendant. It appears that she may have opted for the less experienced, less costly attendant for her sixth confinement, with the added support of her sister-in-law, mistakenly expecting it to be straightforward. Several hours after being summoned, a doctor arrived. He found the poor mother to be ‘almost pulseless’ and provided her with stimulants (most commonly opium or cocaine), while he manually removed her stillborn son.[54] Maternal death was determined to be due to ‘exhaustion’, in the event of delayed medical assistance.

The above accounts are drawn from inquest reports which reveal an abundance of details relating to the birth experience of five pioneer women, their families and their communities. The witness statements of each inquest capture the voices of ordinary colonial Victorians and their actions under difficult and emotional circumstances. The statements also reveal the living conditions in these places, the resources available to women in birth, and the kinds of actions that were taken in a health emergency. These are personal manifestations of the broader historical narrative and as such, details gleaned from these statements contribute to the research of social relationships and arrangements within communities in nineteenth-century Victoria. They provide a window through which to glimpse a crucial aspect of colonial family life and the impetus for social change, particularly in the provision and regulation of rural community health services.

Annie’s Story: Birth and death registrations, local and family history sources

Inquests were held only in the event of some maternal deaths, but other public records and sources help provide a scaffolding within which we can construct the more general experiences of childbirth and early motherhood of Victorian pioneer women.

Annie Dixon had four healthy infants in Hobart and Port Albert before she and her husband Charlie developed gold fever and moved to Castlemaine around 1853. Once there, they erected a tent home alongside thousands of others at the Little Bendigo diggings.[55] By 1854, two of their children had died from dysentery, including their nine-year-old son.[56] When Mrs Dixon went into labour in August 1856, their canvas tent would not have been easy to keep warm, with the temperature as low as 3 degrees Celsius.[57] While some established residents of the Castlemaine diggings had erected bark huts, birth and death registrations tell us that the Dixon family had moved about the diggings, and so they are more likely to have had a tent, which was essentially sheets of canvas thrown over a simple frame of timber which were then pegged to the ground. The floor was dirt, and often a mud-brick fireplace with chimney was added for cooking and warmth. Depending on the floor space, a sleeping roll or a grass-stuffed mattress on the ground served as a bed.[58]

Like Fanny Treadwell, Mrs Dixon was fortunate to have her mother Frances on hand to offer physical and emotional support. Experienced birth attendants were costly; demand was high in these overcrowded locations, and this pushed the price out of the reach of many struggling families.[59] Annie Dixon safely delivered her daughter, with perhaps willow-bark infusion or laudanum (an opiate which was widely available, and often dangerous) to assist with the pain.[60] Sadly, sickness and disease regularly swept through tent communities like this, and both Annie and her baby girl died in the months ahead, of dysentery and intestinal inflammation.[61]

Childbirth attendance was often not limited to the labour itself. ‘Monthly nurses’, as some midwives advertised themselves, were sometimes trained at the Melbourne Lying-in Hospital, and performed a variety of other supportive tasks including ‘cooking, feeding, washing, assisting with ablutions and sometimes sewing clothes for the infant’.[62] The population of rural Victoria was young and overwhelmingly migrant. Many women did not have older family members available to assist in their confinements as they would have had in their country of origin, and experienced birth assistants were in high demand as the population surged.[63] However, experienced midwives charged for their skills, and the level of care which they provided was almost always reflected in the fee that was charged.

Of course, childbirth did not usually end in tragedy – it is partly its ordinariness which lends the confinement experience a cloak of invisibility. Constructing narratives of less dramatic birth experiences is achieved by consulting and combining a set of primary, family and localised sources, and applying these to create a picture of the childbirth experience – the environment, resources and access to medical support. The following case study is illustrative of this approach.

ST Gill, Zealous Gold Diggers, Castlemaine, 1852. State Library of Victoria, Picture Collection, H141536.

Ann’s Story: Civil registrations, passenger records, family history sources and newspaper reports

Despite the dire nature of some challenges faced by pioneer women in Victoria, there were many women whose experience of maternity was improved as a consequence of emigrating. Young immigrant couples were often seeking an escape from a difficult life, which sometimes included the grief of a lost child or unsuccessful pregnancies. Settlement years for these families may in fact have been more stable, perhaps because of improved maternal health or, in some regions, less contact with disease than was experienced in overcrowded industrial cities in their countries of origin.

Ann Battersby and her husband David travelled to Victoria from the British industrial hub of Manchester. The couple sailed on the Southern Ocean with their eight-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, and left behind years of sadness, having lost both their young sons as infants.[64] In their home county of Lancashire, and particularly in the highly urbanised, industrialised towns, rates of infant mortality were the highest in the country for much of the nineteenth century. By the 1870s, health activists, politicians and academics agreed that infant mortality was directly related to increased levels of industrial work for young married women, and to overcrowded living conditions in towns such as Liverpool, Manchester and nearby Sheffield.[65] For Ann, who worked in a woollen factory with very little money to spare, living and workplace conditions would have had a direct impact on her experience of pregnancy, labour and early motherhood.[66] Like many other women, she chose to leave all this behind and try her luck in a new colony.

Like Sarah Davenport’s diary, the Battersby’s shipboard journal records the sad deaths of young children.[67] After 140 days at sea, circumstances quickly improved for the Battersbys once in Victoria. They initially settled in the goldfields stopover township of Kyneton in central Victoria, where they became farmers, adopting a life far removed from the factories of Lancashire. Ann gave birth in 1864 to a healthy daughter, Mary Jane and thereafter produced six more children in fairly quick succession. Each of these children survived childhood, and the family prospered as pioneer farmers in central Victoria.[68] Their immigration story is overwhelmingly positive. As she did not write them down, we cannot know Ann’s experiences of childbirth but there are clues to follow, within birth and death registrations, immigration records, family history sources and newspaper reports.

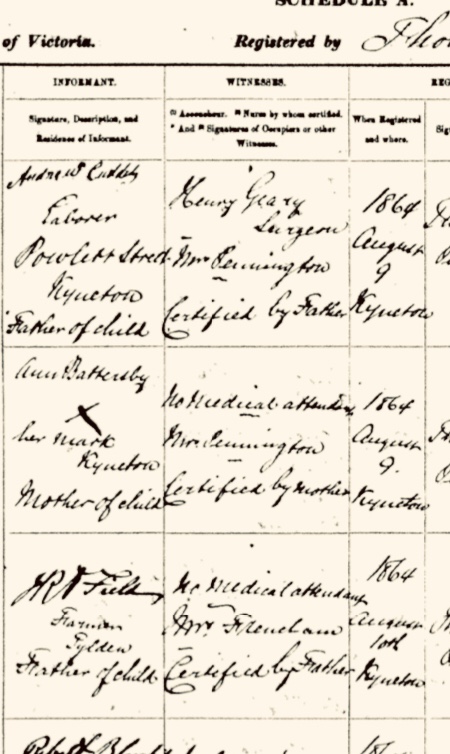

The registration of births in Victoria was compulsory from 1853 onwards and required the inclusion of the names of those who witnessed the birth and their role. Strachan explains that any number of people could be present during the course of a woman’s confinement, including ‘Female midwives, male midwives, nurses, druggists, dentists, herbalists and surgeons.’ She describes it as a pluralist arena, although in very remote areas a woman may labour alone, or in the presence of her husband, or sometimes with the assistance of a local Aboriginal woman.[69]

Ann Battersby’s first two Australian births took place in Kyneton. The 1864 birth registration details tell us that she was attended by a nurse, Mrs Pennington, with no doctor or other witness listed.[70] Mrs Pennington also nursed at the local Kyneton bush hospital.[71] In September 1863, she was charged with ‘injuring the child of William O’Brien, in her professional capacity’. Pennington was found by the judge to have no case to answer, but the reported details of Mrs O’Brien’s confinement provide us with insight into the midwife’s practice, her approach to supporting women such as Ann in their labours and afterwards. A newspaper article of the court proceedings reports that Mrs Pennington had charged the O’Briens £1 for her attendance in 1863. Mr O’Brien had declared in court that ‘I did not cry poor – I would have paid two if she had asked’, which perhaps indicates that Pennington had charged him less than expected. At her death, Sarah Ann Pennington was remembered as generous, offering people loans without documentation.[72] She may not have required payment for all her services, and perhaps asked only what she felt a family could reasonably afford, without loss of pride, although this is speculation. This midwife also originated from a heavily industrialised town in the Lancashire region, and in the absence of kith and kin, an experienced woman with the same regional birthing traditions and a familiar accent may have been some comfort. Pennington attended Ann Battersby’s next confinement also, in 1866.[73]

Birth registration of Mary Jane Battersby, born 8 July 1864, showing attendants at the birth, Victorian Birth Register, registration no. 1864/16028.

Like the O’Briens, Ann and David Battersby had ‘pegged out’ a piece of farmland near Kyneton.[74] The mud slab hut described in court was typical around the township, a form of shelter that could be quickly erected.[75] David was a factory worker rather than a labourer, so their hut, built upon arrival only months before Ann’s confinement, may have been of the more austere variety, with a dirt floor and minimally insulated. Unlike her neighbour, Mrs O’Brien, who had the midwife, her sister and a neighbour in attendance, with her husband fetching spirits and clergy, Ann Battersby is recorded having had just the midwife with her through the birth.[76] The family were new to the township and perhaps had no firm acquaintances in the community, but we see from her later confinements that only one attendant was listed, so it could well have been her preference.[77] It is also possible that her young daughter assisted the midwife. With an established hospital nearby there were local doctors available, but these most certainly charged more than Mrs Pennington, and Ann had given birth safely three times before.

The court witness statements in the case of O’Brien v. Pennington indicate that it was the midwife’s practice to arrive a day or so prior to a labour, or in the very early stages. With her nine-year-old daughter at hand, the Battersbys may not have required practical help with child care and housework, which were often part of the extended services midwives provided in rural areas.[78] The pain relief used by Mrs Pennington was likely to be brandy and cool water, which is what she administered for the O’Brien labour. Good quality water was in abundance around Kyneton, to the great advantage of those pioneer women. Local newspapers of that time reported an unusually dry spell of weather that July – it was mid-winter and with clear skies, temperatures regularly dropped to somewhere around zero degrees or below overnight.[79] Slab huts in this area, with wattle and daub bedroom, were heated with an open fire, which the midwife would ensure was maintained during labour and afterwards, in order to keep mother and baby at a safe temperature.[80] Grehan reminds us that keeping track of time during the stages of birth was made less reliable by the lack of accurate clocks, and often the inability of the working-class poor to read the time. In addition, she points to the quality of light by candle as being detrimental to the work of the midwife in complicated labours.[81] Of course, this only became important when events or actions of those in attendance were under scrutiny. While some buildings in Kyneton at this time did benefit from early gas lighting, in the hut, tallow lamp or candlelight provided low levels of lighting, and the slab hut may not have had a clock to track the passage of time.[82] Traditionally, childbirth in England was conducted in low light, to assist in soothing the mother and maintaining a low blood pressure, so in fact it is probable that many midwives such as Sarah Ann Pennington were accustomed to managing the birth in these conditions.[83] An experienced midwife, even if unqualified, would have a sound sense of appropriate timing and progress in birth, regardless of her education.

For many men in colonial Victoria, the hard work of establishing farmland meant that they were absent from the home for all but their sleeping hours. In addition, childbirth was the domain of women, and David Battersby is not recorded as being present on any of his children’s birth registrations. Witness statements from inquest files, such as that of Susan Cockerill, indicate that in the event of complications, or if the labour was not progressing, the midwife would most likely have sent Elizabeth for her father to fetch a doctor.[84] Ann Battersby’s newborn, however, was safely delivered. While she recovered in the immediate aftermath, and waited for her placenta to come away, Sarah Ann Pennington may have called Elizabeth to fetch some water, and wrapped the infant in muslin. As the only other attendant, Elizabeth may have held the baby while the midwife dealt with the third stage of labour and checked that Ann was comfortable and well. The water would be warmed over the fire until it was the correct temperature for the infant to be immersed. Mrs Pennington would wash baby and dress her in the cotton shift which Ann had prepared, perhaps having hand-sewn it herself, or brought it on their journey. Should Ann have suffered tears during delivery, it was common practice for the midwife to apply clean strips of cloth, boiled in water or scorched.[85]

Again, the O’Brien court hearing provides clues as to the routine the midwife would have followed in the days after Ann Battersby’s confinement. Pennington’s practice was to visit regularly, to ensure that the breastfeeding was established and that mother and baby continued to thrive in the dangerous period immediately after birth. In the case of the O’Briens, Pennington had made several home visits.[86] These follow-up visits were included in the initial charge negotiated between midwife and client. In the months after their daughter’s birth, we can imagine that Ann and David were most concerned about their infant’s welfare having already lost two infant sons to disease. Fresh water, living space and good nursing care with potential access to medical support nearby, along with local food produce, undoubtedly contributed to the health of their Australian-born infants.

Facts gleaned from later family birth registrations and local newspapers begin to construct a narrative of changing social attitudes to pregnancy, birth and maternity, such as increased accessibility of qualified medical attendance and specialised health products targeted at mothers.

In the land selections of 1869, David Battersby was allocated farming land in Dargalong, 110 kilometres north of Kyneton.[87] The nearest village, Murchison on the Goulbourn River, was a very new settlement – most of its few permanent buildings were erected in the 1870s. Family fortunes improved, but later birth registrations indicate that Ann continued to prefer the attendance of just one woman at each of her subsequent four confinements. In fact, for two of her labours, Ann was attended by a Mrs Ewart – her own newly-married daughter, eighteen-year-old Elizabeth, who now resided on a neighbouring property. Despite this, when Elizabeth herself went into labour four months after her mother, she and her husband elected to have both ‘resident surgeon and accoucheur of the district’, Dr McMillan, and local midwife Mrs McKay, in charge.[88]

The small township of Murchison was close to Shepparton, and with its ‘goodly array of commodious hotels and stores’, Ann and Elizabeth both had access to the remedies of the day to ease the discomforts of pregnancy, to provide some pain relief to themselves and care for their infants.[89] By 1875, druggists were advertising Kruise’s Fluid Magnesia for the relief of women’s heartburn and ‘the vomiting, which is so distressing in the early months of pregnancy’, syrup of iodised Horse Radish for ‘weakness of the constitution’ and powders, pills or elixirs of Pepsine, a cure-all for ‘Women’s and Children’s illnesses’.[90] Mothers of this time were subject to public censure and criticism regarding their consumption and behaviour during pregnancy. British newssheets, such as the National Food and Fuel Reformer were largely driven by agendas for single-issue reform and were reprinted in Australian local papers.[91] The Mercury newspaper in 1876 reprinted an article which was essentially a warning on the ‘evil effects of tea-drinking’ in pregnancy.

But perhaps the worst use to which tea is applied by women is the practice of drinking copiously of strong tea during pregnancy, with the idea that it will render their milk abundant. A most unfounded, absurd, and disastrous practice. It is alike injurious to the mother and her offspring; and it may originate the hereditary diseases of successive generations – far beyond the third and fourth.[92]

Pregnancy and childbirth began its march out of the private domain and into the public forum from the 1880s. Medical interest and obstetric intervention, and the pressure which was mounting on unqualified midwives, began to gain traction amongst young rural women at this time.[93] The different attitude towards childbirth, between Ann Battersby and her daughter is perhaps reflective of this growing shift of preference, to engage qualified doctors at confinement. We do not have their first-hand accounts, but the details included in birth registrations, when located within the social context provided by local and regional newspapers, create a sense of their engagement with childbirth practices in the later nineteenth century.

Conclusion

Endeavours to reveal the force of women upon the development of Victoria are enhanced by considering the circumstances faced by these young women building family life in the physically demanding conditions of rural settlements. The women examined in this article had each been dealt a different hand and they each encountered a range of challenges in their experiences of childbirth and mothering. For a great many families, childbirth in the bush was ultimately successful, despite the added hardship and difficulties that the unfamiliar and often harsh physical environment presented. For too many women and their families though, the physical demands of pregnancy and childbirth proved insurmountable, and they were failed by their geographic and temporal place in Australian history.

Birth itself is an event which is both universal across generations and cultures, and unique to each woman. We can never know the truth of another woman’s maternity; the event of birth is one which is mediated by individual experience, culture and personal meaning. Childbearing in nineteenth-century Australia was a fundamental aspect of family and community life and is worthy of focus when considering the challenges of family life in pioneer communities. Despite a dearth of first-hand accounts of childbirth from this era, the construction of individual biographical narratives is made possible with information gleaned from government records and contemporaneous sources. This paper has demonstrated the inherent value of coronial inquest files in illuminating social, domestic and medical details surrounding a woman’s labour in Victoria during the nineteenth century. Other birthing experiences and practices can be pieced together using the facts from a woman’s locality, environment and individual circumstances. Facts and contemporary descriptions of isolation, physical conditions, lack of medical knowledge, the very real threat of death and loss, and the almost complete absence of effective pain relief, help us to appreciate the level of anxiety, danger and discomfort associated with nineteenth-century birth among Victorian woman in bush communities. By examining this evidence, we are able to construct a picture of female pregnancy and childbirth in early rural Victoria and create an informed narrative; an amalgam of personal accounts, facts and a speck of imagination. A hitherto hidden aspect of colonial Victoria is revealed, a reality which appears to have little bearing on the construction of ‘big’ histories but which connects us to the lives of families who came before us; the challenges they confronted and the choices they made. By appreciating the experiences of everyday Victorians of this era, our understandings of the broader, bigger themes of Australian family and social histories become more meaningful.

Endnotes

[1] Glenda Strachan, ‘Present at the Birth; “handywomen” and neighbours in rural New South Wales 1850–1900’, Labour History, no. 81, November 2001, pp. 14–15.

[2] My usage of the terms ‘medical man’ or ‘medical men’ is purposeful, as not all men practicing medical treatment in the colonial era were qualified doctors, and they were often referred to in this way in the primary sources, especially newspaper reports and some anecdotal records. Particularly in remote communities, the qualifications of these men may have been dubious.

[3] Clare Wright, The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2013; Marjorie Theobald, ‘Lies, damned lies and travel writers: women's narratives of the Castlemaine goldfields, 1852–54’, Victorian Historical Journal, vol. 84, no. 2, November 2013, pp. 191–213; Patricia Grimshaw, for example see ’Rethinking Approaches to Women and Missions: The Case of Colonial Australia’, History Australia, vol. 8, no. 3, 2011, pp. 7–24.

[4] Wright, Forgotten Rebels, pp. 45–66.

[5] Ibid., pp. 57–63.

[6] Madonna Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains? Midwives, Nurses and Maternity care in Mid-nineteenth Century Australia’, Traffic, issue 11, January 2009, p. 57.

[7] For example, Georgiana Huntly McRae, 1804–1890, painter and diarist; Lady Jane Sarah Hotham, 1817–1907, governor’s wife. Frances Thiele, ‘Recreating the Polite World: Shipboard Life of Nineteenth-Century Lady Travellers to Australia’, La Trobe Journal, no. 68, 2001, pp. 51–53, available at <http://www3.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-68/t1-g-t8.html>, accessed 10 January 2018.

[8] David Fitzpatrick, Oceans of Consolation: Personal accounts of Irish Migration to Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1995, p. 28.

[9] Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’, p. 57.

[10] Sarah Davenport, Sketch of an immigrant’s life in Australia 1841–1867: the diary of Mrs Sarah Davenport, State Library of Victoria, Manuscripts Collection, MS 9784.

[11] Alan Mayne, ‘Family and Community on the Central Victorian Goldfields’, Alan Mayne and Charles Fahey (eds), in Gold Tailings: Forgotten Histories of Family and Community on the Central Victorian Goldfields, Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, 2010, p. 265.

[12] Madonna Grehan, ‘A most difficult and protracted labour case’, Provenance, issue 8, 2009, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2009/most-difficult-and-protracted-labour-case>, accessed 4 September 2019; Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’; Janet McCalman, Sex and Suffering: Women’s Health and a Women’s Hospital, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1998, p. 23.

[13] Grehan, ‘A most difficult and protracted labour case’.

[14] Geoffrey Chamberlain, ‘British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 99, no. 11, 2006, pp. 559–63.

[15] McCalman, Sex and Suffering, p. 23; Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’, p. 58.

[16] Anne Hardy ‘Commentary: Bread and alum, syphilis and sunlight: rickets in the nineteenth century’, International Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 32, no. 3, June 2003, p. 339, available at <https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg175>, accessed 15 February 2019.

[17] Edward Shorter, Women’s Bodies: A Social History of Women’s Encounter with Health, Ill-Health, and Medicine, Routledge, London and New York, 1990, p. 25; McCalman, Sex and Suffering, p. 23.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., p. 369; Wright, Forgotten Rebels, pp. 169–170.

[20] Lisa Featherstone, ‘Birth in Sydney’, Sydney Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, March 2008, p. 22, available at <https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/sydney_journal/article/view/587>, accessed 23 October 2017.

[21] Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’, p. 55.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Strachan, ‘Present at the Birth’, p. 18.

[24] Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’, p. 55.

[25] McCalman, Sex and Suffering, p. 22

[26] Grehan, ‘A most difficult and protracted labour case’.

[27] PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 232, File 1869/119, deposition of John Bardon, inquest into the death of Margaret Bardon.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Wright, Forgotten Rebels.

[30] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 90, File 1860/55 female, inquest into the death of Mrs Robert Cockrill.

[31] Ibid., deposition of Ann Whalley.

[32] Ibid., deposition of Luisa Buckley.

[33] Ibid., deposition of Dr William Hustin.

[34] Ibid., deposition of Robert Cockrill.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’, p. 56; Strachan, ‘Present at the Birth’, p. 18.

[37] Ibid., p. 13.

[38] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 152, Item 1864/321 female, deposition of Mrs Gordon, inquest into the death of Martha Lithgow.

[39] ‘Charge of Manslaughter against a Medical Man’, Mount Alexander Mail, 7 October 1859, p. 6.

[40] McCalman, Sex and Suffering, pp. 2, 3.

[41] Anna Davine, entry on ‘Muckleford’, in Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia, Cultural Heritage Unit, University of Melbourne, updated 27 May 2015, available at <http://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00258b.htm>, accessed 11 January 2018.

[42] ‘Muckleford Rush’, Mount Alexander Mail, 25 May 1855, p. 2.

[43] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 37, Item 1856/29 female, inquest into the death of Fanny Treadwell.

[44] Ibid., deposition of Mrs Lawson.

[45] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 37, Item 1856/29, deposition of Mrs Lawson, inquest into the death of Fanny Treadwell.

[46] Ibid.

[47] McCalman, Sex and Suffering, p. 109.

[48] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 37, Item 1856/29, deposition of Dr WF Preshaw, inquest into the death of Fanny Treadwell.

[49] Laura Donati, entry on ‘Hospitals’, in Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia, Cultural Heritage Unit, University of Melbourne, updated 27 May 2015, available at <http://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00127b.htm>, accessed 11 January 2018.

[50] Death certificate of Elizabeth Fanny Treadwell, died 21 February 1856, Victorian Death Register, registration no. 1856/2929.

[51] ‘Nurse Lender’ was a rarely used term for local midwife.

[52] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 368, Item 1877/307, deposition of Massimina Sicarani, inquest of Angelina and unnamed child Domenico.

[53] ‘Guildford Borough Council’, Mount Alexander Mail, 25 March 1870, p. 2.

[54] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 368, Item 1877/307, deposition of Dr Norman Gow, inquest of Angelina and unnamed child Domenico.

[55] Ann McVeigh, public member tree on Ancestry.com, available at <https://www.ancestry.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/1180520/person/-1394419731/facts>, accessed December 2017.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology website, ‘Climate statistics for Australian locations’, Castlemaine Prison, available at <http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_088110.shtml>, accessed 15 January 2018.

[58] Caitlin Maher, entry on ‘Tent life’, in Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia, Cultural Heritage Unit, University of Melbourne, updated 27 May 2015, available at <http://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00112b.htm>, accessed 13 January 2017.

[59] Patricia Grimshaw and Charles Fahey, ‘Family and community in Castlemaine’, in Patricia Grimshaw, Chris McConville and Ellen McEwen (eds), Families in Colonial Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985.

[60] Death certificate of Frances Chappel, died 3 February 1892, Victorian Death Register, registration no. 1892/3943; Victorian newspapers are full of reports of people overdosing or being poisoned by laudanum, see, for example, ‘Unintentional Suicide’, Argus, 14 November 1859, p. 7, available at <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5691661>, accessed 4 September 2019.

[61] Death certificates of Ann Dixon, died 25 March 1857, and Susannah Maria Dixon, died 17 September 1857, Victorian Death Register, registration nos 1857/1938 and 1857/5131.

[62] Grehan, ‘Heroes or Villains?’, p. 61; Roger Ustick, The Rabbit-Snatcher: A History of Midwifery Education in the State of Victoria, PhD thesis, Monash University, 1988, pp. 160–176.

[63] Grehan, ‘Heroes and Villains?’, p. 58; Wright, Forgotten Rebels, pp. 162–164.

[64] Death certificate of Ann Battersby, died 27 November 1904, Victorian Death Register, registration no. 1904/12201.

[65] ‘Excessive Infant Mortality in Lancashire’, Bradford Daily Telegraph, 2 May 1874, p. 3; ‘Lancashire Mortality’, Blackburn Standard, 16 December 1876, p. 3.

[66] In the 1851 England Census, Ann is listed as working as a filler in the local woollen mill, see Census returns of England and Wales, 1851, National Archives of UK, Class HO107, Piece 2322, Folio 433, Page 29, database available at <https://www.ancestry.com.au>, accessed October 2017.

[67] David and Ann Battersby’s diary, Southern Ocean, 1863, diary held by a family descendant, author sighted original and in possession of transcribed copy.

[68] Death certificate of Ann Battersby, died 27 November 1904; PROV, VPRS 28/P2 Probate and Administration Files, Unit 451, Item 63/472, David Battersby.

[69] Strachan, ‘Present at the Birth’, p. 17.

[70] Birth certificate of Mary Jane Battersby, born 8 July 1864, Victorian Birth Register, registration no. 1864/16028.

[71] ‘Kyneton District Hospital’, Kyneton Observer, 9 April 1867, p. 2.

[72] ‘Country News’, Age, 10 May 1872, p. 3.

[73] Marriage permissions, Sarah Ann Burke and James Pennington, 11 June 1838, Libraries Tasmania, available at <https://stors.tas.gov.au/NI/1245200>, accessed 7 January 2018; Birth certificate of Agnes Battersby, born 6 April 1866, Victorian Birth Register, registration no. 1864/15499.

[74] PROV, VPRS 629/P0 Land Selection Files, Section 33, Land Act 1869, Unit 66, Item 11882, David Battersby, Barfold, 88A and 88B.

[75] PW Wilkins, ‘A Brief History of Kyneton’, on Wilkins Tourist Maps website, available at <http://www.wilmap.com.au/vic/victowns/kyneton_history.html>, accessed 2 January 2018.

[76] Birth certificate of Mary Jane Battersby, born 8 July 1864, Victorian Birth Register, registration no. 1864/16028.

[77] Birth certificates of George, Fanny, Anna and Alice Battersby, Victorian Birth Register, registration nos 1871/4448, 1873/8752, 1875/8367, 1877/14780.

[78] Joan Gillison, Colonial Doctor and His Town, Cypress Books, Melbourne, 1974, pp. 174–178.

[79] ‘Farm Calendar for July’, Kyneton Observer, 12 July 1864, p. 2.

[80] ‘Police Court’, Kyneton Observer, p. 2.

[81] Grehan, ‘A most difficult and protracted labour case’, p. 13.

[82] Wilkins, ‘A Brief History of Kyneton’.

[83] Judith Schneid Lewis, In the Family Way: Childbearing in the British Aristocracy, 1760–1860, Rutgers University Press, New Jersey, 1986, p. 76.

[84] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 90, File 1860/55 female, deposition of Robert Cockrill, inquest into the death of Mrs Robert Cockrill; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 37, Item 1856/29 female, inquest into the death of Fanny Treadwell, deposition of Mrs Lawson.

[85] Ustick, ‘The Rabbit Snatcher’, p. 176.

[86] ‘Police Court’, Kyneton Observer, p. 2.

[87] PROV, VPRS 629/P0 Land Selection Files, Section 33, Land Act 1869, Unit 66, Item 11882, David Battersby, Barfold, 88A and 88B.

[88] Birth certificates of Fanny Battersby, born 2 April 1873, Victorian Birth Register, birth registration no. 1873/8752, Anna Battersby, born 17 March 1875, Victorian Birth Register, birth registration no. 1875/8367, Janet Hill Ewert, born 16 August 1873, Victorian Birth Register, registration no. 1873/23363.

[89] Gippsland Times, 13 April 1876, p. 4; ‘The Murchison District’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, p. 5.

[90] Kyneton Observer, 27 April 1871, p. 4.

[91] Michelle Elizabeth Tusan, Women Making News: Gender and Journalism in Modern Britain, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 2005, pp. 86–88.

[92] ‘Tea and Tea Drinkers’, National Food and Fuel Reformer, reproduced in Mercury [Fitzroy], 12 February 1876, p. 5. The original publication of this article was credited to the National Food and Fuel Reformer, (London), undated.

[93] Featherstone, ‘Birth In Sydney’, p. 22.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples

![ST Gill, Zealous Gold Diggers, Castlemaine, 1852. State Library of Victoria, Pitctures collections, PCLTFBOX GILL GOLDFIELDS 2.] ST Gill, Zealous Gold Diggers, Castlemaine, 1852. State Library of Victoria, Pitctures collections, PCLTFBOX GILL GOLDFIELDS 2.]](/sites/default/files/files/Provenance%20issue%2017%202019/CallananJM-F02.jpg)