Last updated:

‘Nichola Cooke: Port Phillip District's first headmistress’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 8, 2009. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Liz Rushen.

Well-connected governess Nichola Anne Cooke established the first ladies’ seminary in Melbourne in 1838, just three years after the foundation of the settlement. Conditions were still very harsh and Nichola experienced devastating personal tragedy. She needed courage and enterprise for her school to be successful, and she demonstrated many times that she had both. With the deaths of her family and benefactor within nine months of her arrival in Melbourne, she used her education to provide a source of income, establishing Roxburgh Ladies Seminary on the Batman property,now the site of Young and Jackson’s Hotel in Melbourne.

Nichola upheld her right to stay on the property when the Batman executors tried to force her to leave, and provided stability in the lives of the Batman daughters. She actively engaged the civil courts in protecting her assets at a time when women were not even able to vote, and was one of the first women to own land in the Port Phillip District prior to its separation from the colony of New South Wales.

Nichola Cooke overcame many difficulties to earn her living as a single woman in the fledgling settlement. Her story is remarkable for her links with the development of Melbourne and is important to the history of education in the Port Phillip District.

Nichola Anne Cooke’s will lies quietly in its archive box at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV).[1] How different from the way that she lived her life!

Nichola was born in Ireland, circa 1800, the daughter of Agnes and Thomas Sargent, a Surveyor of Excise and a Sub-Commissioner for Great Britain and Ireland for 41 years.[2] In October 1816 Nichola married Benjamin Cooke, Esq. of Midleton, near Cork.[3] The couple made their home at Ann Street, Cork, but Benjamin died in May 1822, aged 29.[4] It appears that the couple had no children.

Following the subsequent death of her father in January 1828, Nichola moved with her mother and younger sisters to Bristol where in 1832 her mother wrote to the Commissioners for Emigration seeking assistance to emigrate. At this time, the British Government was encouraging impoverished women to migrate to the Australian colonies, but the Commissioners declined to assist the Sargent women, writing ‘it is quite out of their Power to make any further allowance in cases such as yours, than is stated in the accompanying Papers’.[5] The Emigration Commission encouraged the migration of women who had assistance from patrons, benefactors or charitable institutions: the Sargent women did not qualify for the government’s assistance under these provisions.

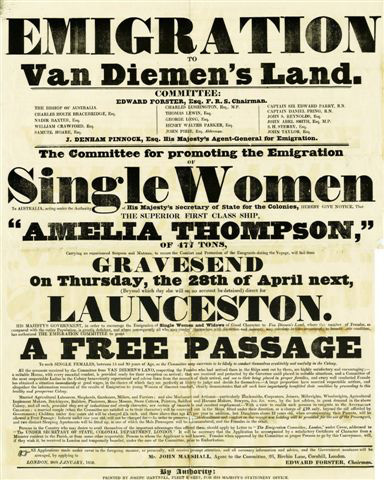

By 1836 there was renewed interest in the possibilities of emigration to the Australian colonies, and the London Emigration Committee had been established to assist women from all backgrounds to emigrate. Agnes and her daughters took this opportunity to establish a ladies’ school in Van Diemen’s Land. Recent research has shown that the ladies’ school enterprise provided a professional path and a livelihood for women without a male breadwinner. Women such as the Sargent family, with teaching experience and some capital, left behind the over-crowded education market in Britain and came to the colonies seeking new opportunities.[6]

On 28 April 1836, Agnes Sargent and her four daughters boarded the Amelia Thompson at Gravesend, arriving at Launceston on 26 August that year.[7] The ship’s passenger lists describe the family as Mrs Agnes Sargent (also Sargeant/Seargeant) aged 50, and her four daughters, who all received the bounty for single women: Mrs MA Cooke a widow aged 28, Catherine A 23, Frances M 20 and Arabella 17.[8] The shipping lists show Nichola’s name as Mrs MA Cooke, but following her arrival she was known as Mrs Nichola Ann/e Cook/e. The age requirement for women receiving the bounty was between 15 and 30 years, and it would appear that Nichola’s age was reduced by a few years to meet the bounty requirements, thus only Agnes had to pay her passage.

Launceston

The arrival of the Amelia Thompson at Launceston was a desperate affair. Unable to find suitable accommodation for the 312 passengers, including 173 bounty women, the commandant in charge of the reception facility, Major Ryan, sent frantic messages to Lieut. Governor Arthur declaring that he had made many enquiries but could not obtain a place large enough for the women who were expected to arrive any day. His last message before the arrival of the ship stated: ‘There is a telegraph signal just made from George Town that a Bark [sic] is in sights from the Westwards and I fear this will prove to be the Amelia Thompson. If so, I am in a pretty mess’.[9] It was the Amelia Thompson and Major Ryan was forced to house the immigrants in a government-owned cottage.

Five weeks after their ship docked at Launceston, Mrs Sargent, her four daughters and Ann Rogers their maid, still remained at the government cottage provided for their reception.[10] The next month, Major Ryan wrote to the Colonial Secretary in Hobart stating that the Sargent women were planning ‘to establish a school for young ladies’, but had been unable to locate suitable premises:

I could not possibly turn this family out in the streets. They are in expectation of getting into a house on the first of next month, after which day I propose … to discontinue this party further on the bounty of Government.[11]

The women eventually moved out of the government cottage and it is believed that they opened a school for girls in Brisbane Street, Launceston. However, things were not going well for the Sargent women in Launceston. A year after their arrival, Agnes petitioned Lord Glenelg for a grant of land, to which she believed she was entitled on account of her husband’s long government service. Writing from Moncton Cottage, Brisbane Street, she stated:

Memoralist and four daughters, influenced by the glowing representations of this colony, emigrated from England … in 1836 with the view of establishing a ladies seminary. That Memoralist on arriving in this “Land of Promise” after encountering all the dangers and disagreeables of a long sea voyage finds herself greatly disappointed in the encouragement held forth to emigrants, add to this house rent and every necessary of life is more than double the ratio here than in England.[12]

Governor Sir John Franklin annotated the letter ‘Answered that under the existing land regulations it is impossible to comply with this application’ and the response from England, when it came, was no surprise: ‘Cannot comply, Downing Street, 26 November 1837’.[13]

Despairing of opportunities in Van Diemen’s Land, the women decided to move on again. They were used to relocating: from their various homes in southern Ireland, to Bristol, to Launceston; and they decided to establish a ladies’ seminary in the new settlement of Melbourne in the Port Phillip District.

Roxburgh Ladies Seminary

Nichola paved the way for the family’s move. She sailed from Launceston on the Gem, arriving in Melbourne on 23 August 1838,[14] just in time to be included in the General Census of Port Phillip, taken on 12 September 1838, where she is listed with John, Catherine and Sarah Hennessy.[15]

Nichola immediately took up the position of governess to John Batman’s children at their home on Batman’s Hill, replacing Caroline Elizabeth Newcomb who had left the Batman employment over a year earlier, in April 1837. Together with Anne Drysdale, Newcomb later established ‘Boronggoop’ and ‘Coriyule’ pastoral properties located on the Bellarine Peninsula.[16]

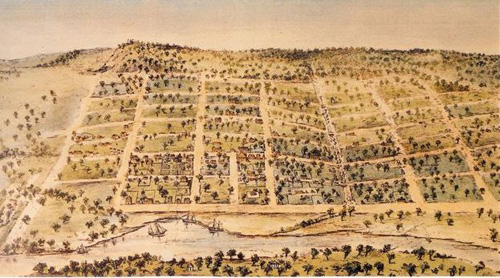

Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

On 1 November 1837, Batman purchased several blocks of land from the Crown, including a slightly swampy half-acre on the corner of Swanston and Flinders Streets to the east of the main settlement, part of Allotment 8 in Section 3 of the Town of Melbourne.[17] He built a seven-roomed cottage named ‘Roxburgh Cottage’ on the western end of the block, later becoming No. 35 Flinders Street, and now incorporated into Young and Jackson’s Hotel. With his business affairs rapidly declining, on 2 August 1838 Batman mortgaged the allotment to Captain Foster Fyans, Police Magistrate at Geelong, for 500 pounds.[18]

Three months later, on 1 November 1838, Nichola rented the cottage from Batman for five years at an annual rate of 100 pounds,[19] establishing Roxburgh (also known as Roxbegh and Rossbegh) Ladies Seminary, reputed to be the first school for girls in the Port Phillip District. The rental was little more than her basic quarterly fee as governess for the seven Batman daughters.[20] With boarding facilities available, the Batman girls were soon joined by other students, including the daughters of Robert Saunders Webb, Collector of Customs, and Maria Matilda, daughter of Captain Benjamin Baxter, later to become Mrs John Edward Sage of ‘Eurutta’, at Baxter on the Mornington Peninsula.[21]

It was a discerning move to establish a school in the cottage, which was ideally located. As the township of Melbourne grew, first a punt was established across the Yarra River, and then a wooden bridge was built at the end of Swanston Street, giving the school a prominence which could not have been imagined in 1838.

Nichola loses her family and her benefactor

Encouraged by Nichola’s success in securing a suitable property, Agnes and her three youngest daughters boarded the schooner Yarra Yarra in September 1838.[22] Tragically, Captain Lancey, the crew and all 18 passengers were drowned when the 45-ton schooner, only built in 1837 in New South Wales, was lost without trace in Bass Strait.[23]

The news of the loss of the ship was a tragedy for Nichola and the new settlement at Melbourne. The Port Phillip Gazette for 24 November 1838 reported:

We must give up … all hopes of the arrival of the Yarra Yarra, for she has been due now some weeks and nothing has yet been heard of her. The loss of this vessel is made more distressing as she had several ladies on board, who have undoubtedly perished with the ill-fated craft. The Misses Sargents who were coming hither with the intention of opening a school, were amongst the number of unfortunates; and it is somewhat singular that the house which Mr John Batman had leased for a term of five years to Mr Howie, and on the protracted absence and supposed death of that gentleman and his family also by shipwreck, had again been leased to the Misses Sargents, is a second time vacant by the loss of the last.[24]

It must have been a devastating shock to Nichola, one which was exacerbated by the death of her benefactor just six months later. During 1838 Batman’s health and marriage were disintegrating rapidly. One commentator has remarked that ‘Christmas 1838 must have been a miserable affair for the Batman family. Eliza was by now totally estranged from John and the children held in the efficient care of Mrs. Cooke’.[25] Batman died five months later, on 6 May 1839.

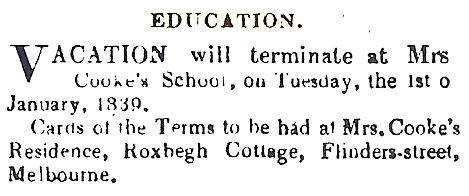

Following Batman’s death, Nichola continued to operate her school on the site. She placed advertisements in the Port Phillip Patriot and the Port Phillip Gazette announcing the end of the Christmas vacation on Tuesday 1 January 1839.[26]

In May 1839 Nichola’s school was listed as the only one of four private schools established in 1838 still operating. Captain Lonsdale, in charge of establishing government in Melbourne, enumerated them on an official return:

Ralph, Walton – 20 to 35 students in daily attendance; established about six months.

Cockane – 10 to 20 students; about two months.

Mrs Coghlan – 20 to 30 students; about five months.

Mrs Cook – 6 to 15 students; about five months.

These schools were held towards the latter part of the year, and are now discontinued, except that of Mrs Cook. The number of scholars are as correct as I can now ascertain.[27]

Captain Lonsdale’s statement that the other three schools failed within a year is confirmed by a letter written on 19 June 1839 by Rev James Forbes stating that the only private place of education in Melbourne was ‘a small school for very young children taught by a female’.[28] While 727 pupils attended church schools at that time, Forbes was lobbying for the government to support the salary of a schoolmaster.[29]

While Nichola was the only person operating a school exclusively for young ladies, newly-arrived settlers lamented the general lack of schools in the new settlement.[30] At the end of 1839 William Locke wrote to his father:

respecting schools here, I must say that Melbourne is not so well off in that point, as I think you could wish. There is one ladies’ school kept by a Mrs Cooke, who is here for some time, but from what I have heard of her, I believe her character is not what at least a schoolmistress’s should be, being what is commonly termed a little flighty, however, as this is only a report I cannot vouch for its correctness.[31]

In today’s terms, we would probably describe Nichola as suffering from ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’. Not only had she lost her mother and sisters in a tragic accident a month after she arrived in Melbourne, but eight months later her landlord and benefactor died. No doubt this created considerable uncertainty for this pioneering schoolmistress.

Mrs Cooke fights to retain occupation

Under the terms of John Batman’s will, the property occupied by Nichola, although mortgaged to Captain Fyans, was left to his eldest daughter Maria. Batman had seven daughters, yet Maria was left substantially more than her sisters. Batman had bequeathed life interest in three other town allotments to his next three eldest daughters, but in the final months of his illness his business affairs deteriorated rapidly and he was forced to sell the properties bequeathed to Lucy, Eliza Junior and Elizabeth Mary. To his three youngest daughters, Batman left only a share in the proceeds of the sale of his personal effects.[32]

On 16 August 1839 Nichola was paid 14 pounds 11 shillings 2 pence by the executors for the education costs of the Batman children.[33] With considerable debts to settle, the executors commenced selling Batman’s assets. In October 1840, the Port Phillip Gazette advertised that the Melbourne Auction Company would auction

by order of the mortgagee – the spacious premises and ground now occupied by Mrs. Cook, as a Seminary for Young Ladies, being corner Allotment 8 Block 5, having frontages to Flinders and Swanston-streets, and near to that part of the Yarra Yarra where the Bridge is to be immediately built.[34]

It appears that the sale did not take place and Nichola advertised the new school term in the Port Phillip Gazette on 2 January 1841. She is listed in Kerr’s Melbourne Almanac and Port Phillip Directory for 1841 as ‘Cook, Mrs., boarding school, Rossbegh Cottage, Flinders Street’. On 16 June 1841, the Gazette contained the following advertisement:

To Let, in the most desirable part of Melbourne – a commodious Residence, consisting of entrance Hall, drawing room, breakfast parlour, two bed chambers and store room, a detached kitchen with loft over, &c. Apply to Mrs. Cooke, Rossbegh Cottage, Flinders-street, or to Mr Reeves, Market-square.

Again, it appears that no-one rented the property and on 6 October that year another sale notice was placed in the Gazette, this time by auctioneer Samuel McDonnell. He stated that ‘this property is one of the most beautifully situated, as well as the most rapidly improving part of the town.[35] Nichola, however, asserted her right to occupy the property. Three days after the McDonnell advertisement, she inserted a notice in the paper stating:

Mrs. Cooke begs to intimate to the public, that she is fully determined to retain the possession of the cottage and allotment occupied by her, according to her original agreement with the late Mr Batman, and that two years of her time are yet unexpired.[36]

A week later on 13 October 1841, Edward Newton, one of the trustees of the Batman estate, placed a notice in the paper stating that ‘no such agreement, either written or verbal, ever existed’. He claimed that Nichola’s statement ‘if credence be given to it, will depreciate the value of the property at the time of sale … and thus hurt the interests of the family of the deceased.’[37]

The ‘interests of the family’ presumably relate to Maria Batman, to whom the allotment occupied by Nichola had been bequeathed by her father. Earlier in 1841, Maria then aged 16 had married John Kenny, a 26 year-old customs clerk. Within six months she had given birth to a baby who died, and this event was closely followed by the death of her husband in August that year.[38] It is apparent that Nichola and Maria retained a good relationship, as, after her husband’s death, Maria lived with Nichola at Flinders Street for more than a year.[39]

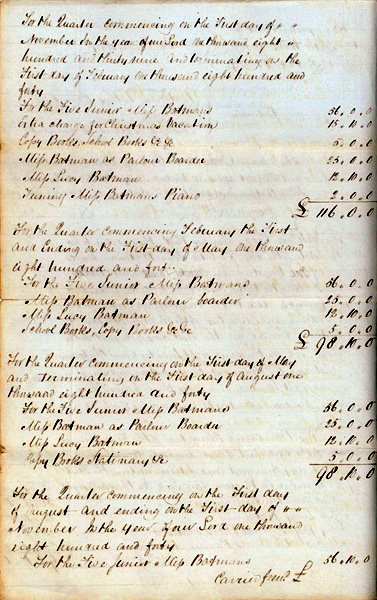

Nichola continued to operate her school on the property throughout the 1840s, and the older Batman daughters lodged with her during this time. When the outstanding accounts of the Batman estate were finally drawn up, it was revealed that for the period from 1 August 1839 until 25 March 1843 Nichola was owed 199 pounds 3 shillings ‘for board, maintenance, education and other expenses’ for the Batman children. The total amount expended on the children in this time had been 989 pounds 3 shillings and Nichola had received 790 pounds, leaving a balance due to her of 199 pounds 3 shillings. This amount of nearly 1,000 pounds included tuition and board for the Batman daughters, including board over Christmas vacations, books and shoes, tuning of piano, extra charges for Eliza Junior as a ‘parlour boarder’, Maria’s board, and the cost of a piano bought for Maria.[40]

These amounts were finally settled by PW Welsh, a Melbourne merchant who had been appointed the second trustee of the Batman estate.[41] The Port Phillip Gazette of 27 January 1844 notes that Nichola imported a case of fruit from Hobart per Lillias.

In a hearing regarding the progress of the Batman will held on 25 April 1842, it was noted: ‘No rent received from Mrs Cook the amount having been allowed in part payment of the education of family of the deceased. Payable quarterly … The tenant refusing to give up possession’.[42] In another hearing on 10 September 1844, Welsh stated: ‘No rent has been paid to Receiver for this portion of the Estate … It was sold under the Mortgage but Title defective and Mrs. Cook [sic] refuses to give up possession’. The settlement of the Batman will dragged on and Nichola stayed put. In a deposition the following year, she finally had a chance to outline her reasons for remaining at the property:

I took the House I now live in from the Testator during his lifetime. I took it on the 1st November 1838. I took it for five years and a Lease was to have been granted. The rental was £100 per annum. The rent was always to be settled in acct with the Testator quarterly. The account was for the education of the children. I have never paid any rent – it was always settled in a/c.[43]

It appears that Nichola won her fight to stay at the property, as in a further hearing on 1 May 1845, she was still stated to be the occupant at Flinders Street.[44]

A feisty woman

Nichola Cooke, a long-term resident with a relatively high profile, demonstrated her determination many times. On one occasion, in November 1843, she was brought before the Petty Sessions for having an unregistered dog and was lucky to have the case dismissed. In other cases that day, one defendant under the same charge was fined 20 shillings with costs and six were fined 10 shillings. Nichola’s was one of only two cases to be dismissed.[45]

An early-twentieth-century writer has given us a colourful description of Nichola:

Mrs. Cooke … seems to have been a woman of very strong personality and great determination. They tell of her that when the collection of municipal rates was first mooted she announced her intention never to pay them. ‘When they come to me,’ said this inflexible woman, ‘they will find Moll Thompson’s initials on my purse!’ On another occasion, when riding through ‘the village’ she met some unhappy man who had incurred her displeasure. Brandishing her horsewhip over his head, she said with more passion than humour, ‘Consider yourself horse-whipped, Sir!’[46]

With the opening of the bridge across the Yarra at the end of Swanston Street in October 1845, it is likely that Nichola had greater access to pupils living south of the river. She is listed in both Mouritz’s Almanac and Directory of 1847 and the Port Phillip Patriot Almanac for that year as ‘preceptress’.[47] The City of Melbourne Rate Books for 1843 to 1850 list her as the occupant at Flinders Street, in a property valued initially at 30 pounds, growing to a rated value of 36 pounds by 1850, when the property is stated as including a house of seven apartments and kitchen. In 1847–48, when the property was still valued at 30 pounds, the surrounding properties were valued between 28 and 140 pounds. In both 1847 and 1850, Foster Fyans (to whom John Batman had mortgaged the property in 1838) was stated to be the Agent.[48]

On 4 December 1850, Captain Fyans foreclosed the 1838 mortgage and sold the allotment to Thomas Herbert Power and Matthew Hervey for 1,500 pounds.[49] Nichola did not immediately vacate the property as she is listed in the 1851 Victoria Directory as still living at that address.[50] The 1851 report by HCE Childers, the first Inspector of Schools in Victoria, stated that there were 24 private (or dames) schools operating in the newly-declared colony of Victoria and it is likely that Nichola’s Roxburgh Ladies Seminary was one of these schools.[51]

By 1853 Nichola no longer occupied 35 Flinders Street, as the Melbourne Directory for that year lists this property under Geo M. Whitehead & Co., Merchants.[52]

Purchase of a property

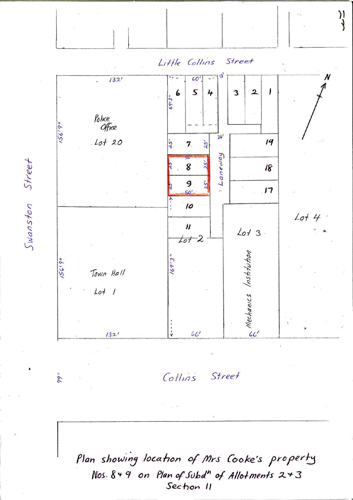

While insisting on her right to occupy the Flinders Street property and remaining there until at least 1851, ten years previously Nichola had purchased her own property. On 29 March 1841 she paid 29 pounds to Captain Charles Scott for Blocks 8 and 9 of Allotments 2 and 3, Section 11 (Town of Melbourne). These blocks were located in a now non-existent laneway off Little Collins Street, behind the present-day Melbourne Town Hall.

The two blocks of land were in a row of five, each 25 feet wide by 50 feet deep. On 1 October 1844, Nichola entered into an agreement with John Sullivan to rent the blocks for 5 pounds per annum. Fifteen years later, on 20 January 1859, she leased the blocks to John Sleight for a rental of 50 pounds per annum. This arrangement held for eight years until, on 24 May 1867, she sold the blocks to John Sleight for 250 pounds.[53]

Return to Ireland

In 1855 Nichola Cooke is listed in the Melbourne Commercial Directory as keeping a boarding house in Stephen (now Exhibition) Street, on the corner of Collins Street.[54] She returned to Ireland after this time, as her name is not listed in any Melbourne directory after 1855, and by 1867, when she sold her land off Little Collins Street, Nichola was living at Armagh, Ireland. It is possible that she was the Mrs Cooke who sailed to London from Melbourne on the Copenhagen in February 1862.[55]

On 18 October 1867, five months after the sale of her land, Nichola died at Enniskillen in the County of Fermanagh, leaving an estate in Melbourne valued at 538 pounds 17 shillings 5 pence. She had 283 pounds 12 shillings in the Victoria Life and General Insurance Company and Savings Institute, 55 shillings 5 pence outstanding rent from John Sleight, as well as 250 pounds in the hands of the administrator (most likely the proceeds from the sale of her land). She also had at least 100 pounds in the Enniskillen branch of the Bank of Belfast.[56]

Under the terms of her will, drawn up just six days before her death, the first beneficiary was her nephew Thomas Blennerhassett Sargent, surgeon, who was to receive 270 pounds of the money remaining in the bank account in Melbourne. The executrix, Sarah Anne Blennerhassett, widow of Enniskillen, described by Nichola as her ‘dear friend’ was to receive 269 pounds which Nichola stated she ‘shortly expect[ed] to arrive from Melbourne being the produce of a sale of property there and some interest money’. Sarah’s son, Richard Henry Blennerhassett, also a surgeon, was executor and another beneficiary to the sum of 100 pounds. His wife, Elizabeth Anne was to receive Nichola’s ‘rings, trinkets and jewellery and all my personal effects’.[57]

The Blennerhassetts were a well-connected Protestant Ascendency family.[58] In 1812, Nichola’s elder sister, Mary Ann Sargent married Richard Balmer, a Lieutenant in the Armagh Militia.[59] They had one son, Benjamin Blennerhassett Balmer whose name, along with that of Nichola’s nephew Thomas Blennerhassett Sargent, indicates several connections to the wealthy Blennerhassett family.

Nichola’s will was challenged by her nephew, Thomas Blennerhassett Sargent, on 26 May 1868 at the Probate Court in Dublin. He lost the case and the will was upheld. John Matthew Smith, a solicitor of Chancery Lane, Melbourne, was appointed the Melbourne administrator to realise Nichola’s assets and the will was proved in the Supreme Court of Melbourne on 6 November 1868.[60]

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VPRS 28/P1, Unit 17, Item 7/116.

[2] National Archives UK, CO 208/78, Sargent to Secretary of State, 10 March 1837.

[3] Cork mercantile chronicle, 31 October 1816.

[4] Cork mercantile chronicle, 30 May 1822.

[5] National Archives UK, CO 385/14, Elliot to Mrs Agnes Sargent, 31 July 1832.

[6] Marjorie R Theobold, ‘Women and schools in colonial Victoria, 1840-1910’, PhD thesis, Monash University, 1985.

[7] Archives Office Tasmania (AOT), CSO 1/872/18447.

[8] AOT, CSO 1/872/18447 and National Archives UK, CO 280/67.

[9] AOT, CSO 1/18447, Ryan to Colonial Secretary, 25 August 1836.

[10] AOT, CSO 1/868/18447, Ryan to Montague, 5 September 1836.

[11] AOT, CSO 1/18447, Ryan to Montague, 24 October 1836.

[12] National Archives UK, CO 208/78, Sargent to the Secretary of State, 10 March 1837.

[13] National Archives UK, CO 208/78, Sargent to the Secretary of State, 10 March 1837, Annotation, 26 November 1837.

[14] Launceston Advertiser, 30 August 1838. The Gem was owned by John Batman, and sold for 1,219 pounds following his death.

[15] Michael Cannon and Ian MacFarlane (eds), Historical records of Victoria: foundation series, vol. 3, The early development of Melbourne, 1836-1839, VGPO, Melbourne, 1984, p. 438.

[16] According to Rankin, Newcomb initially taught the Batman children in their home on Batman’s Hill, then at ‘Roxburgh Cottage’ (DH Rankin, The history of the development of education in Victoria 1836-1936, Arrow, Melbourne 1893, p. 25). However, as Batman bought the site in November 1837, the cottage was not built prior to Caroline’s departure in April that year. Billot confirms the view that it was Nichola Cooke who turned the small cottage into a school: see CP Billot, The story of John Batman and the founding of Melbourne, Hyland House, Melbourne, 1979, pp. 265-8; see also Jean I Martin and PL Brown, Australian dictionary of biography – online edition entry for Anne Drysdale and Caroline Newcomb available at <http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A010556b.htm>, accessed 4 June 2009.

[17] Leslie A Schumer, ‘Melbourne’s most famous hostelry: Young and Jackson’s’, Victorian historical journal, vol. 54, no. 1, March 1983, pp. 41-5.

[18] ibid.

[19] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 2, Item 68, Statement of Tracts: real estate belonging to Batman [undated].

[20] PL Brown, ‘Batman, John (1801-1839)’, Australian dictionary of biography – online edition, available at <http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A010066b.htm>, accessed 8 October 2009.

[21] T O’Callaghan, ‘The beginnings of school-keeping in Victoria’, Education gazette and teachers’ aid, 19 April 1921, p. 66; ‘Death of Mrs. Sage’, Victorian historical journal, vol. 11, no. 44, 1927, pp. 279-80.

[22] Launceston Advertiser, 27 September 1838.

[23] Harold Salter, Bass Strait ketches, St. David’s Park Publishing, Hobart, 1991, p. 313.

[24] See also Port Phillip Gazette, 30 August and 27 September 1838.

[25] Billot, The story of John Batman, pp. 265-8.

[26] Port Phillip Patriot, 30 December 1838; Port Phillip Gazette, 29 December 1838 and 1 January 1839. See also ‘Garryowen’, The chronicles of early Melbourne 1835-1852, Fergusson and Mitchell, Melbourne, 1888, Vol. 2, p. 634.

[27] Cannon, The early development of Melbourne, p. 613.

[28] Robert D Boys, First years at Port Phillip, Robertson and Mullens, Melbourne, 1935, p. 83.

[29] Cannon, p. 634.

[30] LJ Blake, Vision and realisation: a centenary history of state education in Victoria, Education Dept of Victoria, Melbourne, 1973, vol. 1, pp. 3-5.

[31] Royal Historical Society of Victoria, m/s 17620, Letters from Melbourne, 7 December 1839.

[32] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 1, Item 1, Copy of late John Batman’s Will, filed 24 March 1843.

[33] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 1, Item 8, Examination and break-down of entitlements of Will.

[34] Port Phillip Gazette, 14 October 1840. With thanks to Ken Smith for this and the other Port Phillip Gazette references December 1838 – January 1844.

[35] Port Phillip Gazette, 6 October 1841.

[36] Port Phillip Gazette, 9 October 1841.

[37] Port Phillip Gazette, 13 October 1841.

[38] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 1, Item 71, Statement of Batman’s debts and general costs, directions included to auction property; also Victorian Index to Briths, Deaths & Marriages, registration nos 4334/933 (marriage, 1841), and 3610/1072 (death, 1841).

[39] Michael Cannon, Old Melbourne Town before the Gold Rush, Loch Haven Books, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 81-2.

[40] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 2, Item 54, Affidavit and charge of N Cooke.

[41] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 3, Item 148, Answer of P Welsh.

[42] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 3, Item 6, Rental of estate of Batman and general account of receiver.

[43] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 2, Item 88, Masters book of proceedings under decree of 26 January 1843.

[44] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 1, Item 6, Rental of estate of Batman and general account of receiver.

[45] PROV, VPRS 51/P0, volume 3, Deposition Book and Petty Sessions Register No. 5.

[46] H Daniell, ‘The development of girls’ education in Victoria’, in Frances Fraser and Nettie Palmer (eds), Centenary gift book, Robertson and Mullens, Melbourne, 1934, p. 110.

[47] Kerr’sMelbourne almanac and Port Phillip directory, Kerr and Holmes, Melbourne, 1841, p. 239; JJ Mouritz (comp.), The Port Phillip almanac and directory for 1847, Herald office, Melbourne, 1847, p. 74.

[48] PROV, VPRS 3102/P2, Unit 1, City of Melbourne Rate Book 1843/44.

[49] PROV, VPRS 42/P0, Unit 1, Item 25, Account: money expended on Batman’s children [undated].

[50] Victoria Directory, [s.n.], Melbourne, 1851.

[51] Carl Bridge, ‘Victoria’s Schools in the 1850s’, in Victorian Historical Journal, Vol. 54 (1), 1983, pp. 58-61.

[52] The New Quarterly Melbourne Directory, Melbourne [s.n.], 1853.

[53] Land Victoria, E.2871 (October 1844) ; 97.85 (20 January 1859) ; 176.285 (24 May 1867).

[54] Joseph Butterfield (comp.), Melbourne commercial directory for 1855, James J Blundell, 1855. Further searches of Victorian directories after this date failed to locate her.

[55] PROV Index to Outward Passengers to Interstate, UK, NZ and Foreign Ports, 1852-1896, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration/outwards-passenger-lists>, accessed 29 March 09.

[56] PROV, VPRS 7591/P1, Unit 30, Item 7/116.

[57] PROV, VPRS 7591/P1, Unit 30, Item 7/116.

[58] Blennerhassett Family Tree website, available at <http://blennerhassettfamilytree.com/>, accessed 15 March 2009.

[59] Cork mercantile chronicle, 24 January 1812.

[60] PROV, VPRS 7591/P1, Unit 30, Item 7/116.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples