Episode 15: Travelling to Tomorrow: Extraordinary Australian women of 1920s America

Host: Kate Follington

Guest: Dr Yves Rees, Historian and Author

Duration: 49.47min

Podcast theme: Jack Palmer

Originally recorded at the Victorian Archives Centre, 2024

Dr Yves Rees Guest

00:00

She comes back to Australia to visit family but also spread the word about modern life and art in Melbourne, and so this is an example of this trajectory of Australian women kind of bringing back modern ideas from the US. She comes back in 1935 and has an exhibition of her latest work, which is the scandal of the year.

Kate Follington Host

00:27

That's historian Dr Yves Rees talking about artist Mary Cecil Allen, an Australian who lived in Greenwich Village, New York, in the 1920s and 30s. Keep listening to find out how Cecil Allen handled the controversy over her new modernist ideas. Today's episode of Look History in the Eye is about the forgotten diaspora of hundreds of young Australian women who headed to America to make their mark at the beginning of the 20th century. They were rebellious and adventurous, and they wanted something bigger for their lives that they couldn't find here.

Dr Yves Rees Guest

00:57

Australia was the first country in the world to give white women full political rights, the right to vote and stand for parliament. That had a huge effect internationally. You know Australia was really seen as a global trailblazer in this front and then that shifts quite dramatically in the 1920s. The narrative quickly changes from Australia being at the global forefront to Australia lagging behind.

Kate Follington Host

01:22

Frustrated women headed to the exciting shores of California or to the creative movements on the rise in New York, and what an impact they had in art, political policy, literature, sport. Their ideas were not just adopted over in America, but they eventually were adopted here in Australia as well. And yet their names remain relatively unknown. So let's change that and share their names over dinner tonight Cecil Allen, Persia Campbell, May Lahey and Isabel Lethem. My name's Kate Follington and you're listening to the podcast Look History in the Eye produced by Public Record Office Victoria, the archive of the state government. We meet people who dig into archival boxes, look history in the eye and bother to wonder why, and you can view a transcript and images of the people featured in this story by searching Look History in the Eye podcast online. This is a recording of a lecture offered by historian Dr Rees in 2024 at the Victorian Archive Centre about four Australian women who featured in Eve's new book Travelling to Tomorrow. Enjoy and please share this episode with your friends and family.

Dr Yves Rees Guest

02:49

When I was in my early 20s I lived for a period of time in San Francisco because my then partner was working in Silicon Valley and I was just kind of enraptured by the modernity and the sense of ambition and optimism of the United States. You know, I was very aware of all the kind of the structural problems, the structural racism, the settler, colonial history of the US, but I was sort of really taken aback by how much I was energised by this sense of modernity and possibility that I found there, particularly so because my encounter with the US happened on the back of spending a year in London. I'd gone to London to do a Masters in History and I'd gone to London in that really kind of typical settler, Australian, cringing, colonial way of thinking. You know, oh, I'm a you know this kind of provincial from the colonies and I'm going to get my you know, my educational polish in London and sort of go back to my spiritual home, which was not how it turned out. You know, I arrived in London and I faced a kind of barrage of convict jokes and I, you know, found very retrograde attitudes. But I also found London just a kind of really alien and cold and unwelcoming place that I did not feel connected to in any way. And so I guess my experience of, you know, feeling alienated in the UK and then going to the US and feeling a sense of kind of connection and excitement and belonging even got my historian brain.

04:34

Thinking about the background to this felt like there was a very familiar cultural narrative about Australians going to London, whether, to you know, seek that kind of polish, to you know, prove themselves as creatives, as artists, as actors or to study at Oxford and Cambridge. That felt very kind of entrenched in the stories we tell about ourselves. But I felt like I didn't know any history about Australians going to the U.S and what might have, you know, taken them there instead and what they found there and what they brought back. So I guess I started looking into this question, wondering if there was a kind of a backstory here that might tell us interesting things about Australian history and Australia's place in the world, and what I found surprisingly is that there was.

05:35

I was, you know I originally found one particular woman called Mary Cecil Allen, who I'll talk about a bit more in a moment, who I did my honours thesis on back in the day, and she was a kind of Australian modernist artist who spent time in New York from the 1920s onwards, and I wondered, you know, are there other women like her? And I quickly discovered there were so many. In total I found there were about, or I compiled a list of around 700 Australian women who in the early decades of the 20th century, went to the United States, not as tourists but, you know, out of their own volition for career, for adventure, for personal development of some sort. And this was an incredibly diverse cohort of women. It ranged from, you know, the celebrity decorator with blue hair, then there was the single mother who advised JFK in the Oval Office, there was the Christian nudist with a passion for almond milk, and then the wheelchair user who wrote bestselling novels and a cigarette-loving nurse who dodged immigration control. So I kind of had this very kind of vibrant, exciting cohort. But what I think united them was this sense of a, you know, traveling overseas to pursue their own ambitions at a time when that was obviously very unusual for women and going against the kind of the gravitational force of London and seeking out this kind of alternative metropole of the United States instead.

07:28

So many years later, this kind of cohort of 700 women I've distilled into this book, which focuses on 10 of the you know characters I discovered, and so I mainly tell the story of 10, some of whom I'll talk about today. I won't have time to talk about all 10. But my research and my argument, I suppose, is also resting on this bigger research of 700 characters, and I suppose I'm seeking to do two main things in this book. Firstly, is to kind of restore the stories of these women to our historical consciousness because, as we'll discover, these were extraordinary people who you know were internationally trailblazing, were often very well-known overseas but have been forgotten in Australia because of factors I'll go into in a moment. So, I wanted to restore their narratives to our historical memory.

08:29

But also, I guess I began to read this travel trajectory, this kind of diaspora of women, as a way into kind of telling a different story about Australian-US relations. You know, we do know that there is a history of Australian-US connections kind of dating back to, you know, throughout Australia's colonial period. But the narrative that often gets told is that the special relationship between Australia and the US really starts in World War II, which is the beginning of formal diplomatic ties between the two nations. It's when we exchange ambassadors, and you know, of course, that collaboration, the war in the Pacific, leads into the ANZUS Treaty in 1951, which kind of, you know, takes us into the special relationship that continues, for good or for ill, to this day. And that narrative was all true.

09:24

But I guess I, you know, was very influenced, my thinking was very influenced by a school of historical literature that's developed over recent decades which stresses that, you know, relations between nations are not only the domain of men and diplomats and formal international relations, but that you know culture and travellers and you know women can play a really important role in how nations understand each other. So I guess looking at these women in this book began to see them as kind of presenting an alternative origin story of Australian-US relations, because these women all became totally in love with America and most of them came back to Australia and became huge boosters for the idea of a kind of Australian turn to America, for the idea of a kind of Australian turn to America as well as kind of calling for Australia to kind of be influenced by American ideas in specific professional contexts. So I'm kind of making the argument that these women were sort of geopolitical avant-gardists. They're kind of at the forefront of a kind of cultural turn towards America which in a sense is laying the foundations for the more formal strategic turn of the sort of 1940s onwards. And I, just before I get into the details of some of the specific women, I just sort of want to briefly reflect on why they've been forgotten when they were, as I argue, so significant.

11:15

And I think there's two main things going on here. I think the first is related to gender. Unsurprisingly that, Australian history is still so wedded to masculinist narratives of nation and there's been little place in those stories for women such as the people in this book. But I think there's also something else going on about, you know, the kind of marriage of convenience between historians, the history, profession and nation as well, that as transnational figures these women kind of fell out of the story of Australian history because they left and they often lived overseas most of their life but that, as you know, Australian-born people, they didn't quite fit into the main narrative of American history either. So they sort of fell between the two cracks of different national stories. So let's get on to talking about some of these individual people, people.

12:35

So, I wanted to start by looking into the story of Mary Cecil Allen, because she was really the as I mentioned earlier, the character that brought me to this diaspora. Mary Cecil Allen was born into quite an elite Melbourne family. Her father was a professor of medicine at the University of Melbourne and she grew up very much in kind of establishment Melbourne circles, studied art at the National Gallery of Victoria and then in the 1920s was sort of a rising star of the Melbourne art world and one of the few women to sort of make a mark in that space. She was doing her own painting, but she also became the first woman to be appointed a guide lecturer at the National Gallery of Victoria and sort of developed this reputation as an art educator alongside that of an artist. Now, in the late 1920s, she travels overseas because she's invited to be the personal guide to sort of the great art galleries of Europe by a wealthy American woman, Florence Gillies, and so they go on this kind of fantastic eight-month tour of Europe and Mary's about to come back to Australia, she's even kind of bought her passage on boat to return home to Sydney. But she gets a last-minute invitation to lecture for the Carnegie Trust in New York and she sort of thinks this is an interesting professional opportunity, I'll go to New York, spend a few months there and then kind of come back to Melbourne and continue my life.

14:15

And then what happens is what ends up happening to so many of these women is they kind of go to America thinking it'll be a particular limited period, and they fall in love and they get stuck, they don't leave. They find this kind of world of greater professional opportunities for women, a sense of just, you know bigger audiences, you know bigger horizons more generally, and then they want to stay. So Mary goes intending to stay a few months and she stays eight years and while she's in New York she kind of has this conversion to modernism, basically both in terms of modern art and a modern lifestyle. So when she left Australia she's quite conservative still in her artistic practice, sort of reflecting the prevailing conservatism of Australian art world at the time and the deep hostility to modernism. But in New York she gets excited by the possibilities of abstraction and the possibilities of modern art to not just depict the world but in a kind of photographic sense, but to kind of bring to life the spirit and the essence of the artist's vision of the world. She also moves to Greenwich Village and kind of explores the possibility of independent modern living. And kind of explores the possibility of independent modern living.

15:50

And Mary, I think, is interesting because she's one of several women in this study who has sort of hints of queerness in her life, you know, unsurprisingly it's very difficult to say for sure whether she may have been same-sex attracted or, you know, had relationships with women, but there's um in in this period of living in America she kind of undergoes what I'd call a sort of uh shift towards gender non-conformity. She starts having wearing quite masculine attire, um crops her hair, begins to wear pants all the time. She also, um, increasingly goes more and more by her middle name, Cecil, and you know, by sort of midlife she's universally known as Cecil Allen and also, you know, starts to mix in very queer circles, both with her circle of friends and the neighbourhoods she chooses to live in. So of course, I think you know it's very problematic for historians to kind of be retrospectively assigning kind of contemporary sexual and gender identities to historical figures. I think there is, you know, persistent hints of queerness in Alan's trajectory that I think are important to flag. So she undergoes this modern conversion in New York and then she comes back to Australia to visit family but also spread the word about modern life and art in Melbourne, and so this is an example of this trajectory of Australian women kind of bringing back modern ideas from the US.

17:38

She comes back in 1935 and has an exhibition of her latest work, which is the Sc scandal of the year. Like it's hard to kind of exaggerate how shocked the kind of conservative, uptight Melbourne punters are by what we might now regard as very tame abstraction. But you know her exhibition opening is completely packed out but not everyone's too scandalised to buy the paintings. You know there's sort of her former art teacher, max Meldrum, runs into her on the street but he crosses to the other side of the street because he's so horrified by her conversion to modernism. So it's all very dramatic.

18:24

But the interesting thing about this is Mary, who has kind of really honed her skills as an educator and lecturer on modern art in New York. She launches a kind of year-long campaign to try and change hearts and minds about modern art in Melbourne. So she's giving these kind of very, very large, oversubscribed public lectures at the National Gallery of Victoria that are attracting, you know, about 1,000 people each sort of standing room only, that are then being reproduced verbatim in the press and she's sort of giving modern art 101. She's sort of saying, you know, you might feel confronted by the sort of the distortions of Picasso's cubism. It's very, you know, it doesn't look like something that requires a lot of technical skill, but it's actually really exciting and really innovative and opening up new horizons for artistic expression. And let me explain how. And opening up new horizons for artistic expression and let me explain how. And this is actually incredibly effective.

19:29

By the time she leaves Melbourne after a year here she's sort of been credited with kind of, you know, completely changing attitudes towards modern art, like at least opening the door towards people being sympathetic towards it, which I think is really significant because I think she's been, she's one of the key figures that sort of lays the foundation for the flourishing of modern art. We see in Melbourne in the 1940s with the Heide School and people like Sidney Nolan, kind of forging a distinctively Australian modern art and her kind of distinctively Australian modern art and her kind of educational pursuits and ideas she brought back from America was really key to that. And then she does it again in the 1960s. So she goes back to America spends several more decades over there. But in the early 1960s, when American abstract expressionism is of course the kind of most exciting thing in the art world, she comes back and starts lecturing on Pollock, when no one has heard of Pollock in Melbourne, and you know I'm sure many of you will be familiar with how controversial it was when Whitlam bought Blue Poles in the 70s and so even a decade before that. She's really at the cutting edge of challenging local audiences to see that level of abstract expressionism as something artistically valid. So I could say a lot more about Mary, but I want to move on to someone else.

21:01

The next figure I'd like to spotlight is the lawyer May Lahey, and she's a really interesting figure because on one level she could be claimed as Australia's first female judge. So according to kind of conventional wisdom, Australia’s first female judge was Dame Roma Mitchell, who became a judge of the Supreme Court in South Australia in 1965. And it is absolutely true that that's the first woman to be a judge in an Australian jurisdiction. But almost 40 years earlier the Australian May Lahey became a judge in California, in Los Angeles, and her trajectory is a kind of insight into the greater professional opportunities that white Australian women discovered in the US that she still, as a lawyer, encountered a huge amount of sexism and discrimination in California, but it was, you know, a fair sight better to what was going. Encountered a huge amount of sexism and discrimination in California, but it was, you know, a fair sight better to what was going on in Australia, where there was basically no women lawyers of her generation working at all. So she is from Queensland.

22:18

She goes to Los Angeles in 1910 to study law at the University of Southern California, and this is a time when there's not a single woman judge in the state of Queensland. And so, even though you know, women law students are a minority in her cohort, there's still enough of them that you know. She sort of has a sense of camaraderie and community there. May Lahey is the star of her cohort and she very quickly sort of decides this is a place for her, she's going to not only do her degree in California, she's going to stay and develop a career there. So she takes out US citizenship and forges a career as an attorney in the 1910s and 20s, and then in 1928, she's appointed the second female judge in California. She's appointed by a Republican governor. She, you know, is quite active as a political Republican at the time and she's sort of celebrated. This appointment is seen as hugely significant both within California or around the US and within Australia. So even though she's sort of virtually forgotten in Australia today, at the time of her appointment she's sort of hailed across Australia as our first woman judge and there's a real sense of pride that an Australian woman has succeeded so much on the international stage. But it's also provoking interesting local discussions about. You know, why can Australian women succeed to such heights internationally but why aren't we having Australian women judges here? So it's sort of prompting broader reflections about the state of women in their professions in Australia. May kind of goes on to become very influential, not only as a jurist but as a kind of women's rights activist in the US. At the national stage she's a very vocal advocate for the ERA throughout the 1930s, 40s and 50s and she's sort of one of the rare women in this study who ends up living her entire life in the US. She never comes back to Australia, which I think is interesting because she's still got a lot of family here and certainly had the means to come back. But for whatever reason she's sort of very much.

25:02

Another of my favourite characters is the swimmer Isabel Letham. Now Isabel Letham is probably the woman in this book who's the best well-known before. I got onto her, but she's known for a different reason that I'm interested in her. So the kind of conventional narrative about Isabel Letham is that she's one of the first women to surf in Australia. So she was a teenage girl in 1915 living in the northern beaches of Sydney, a very athletic, sporty girl, and in that summer Duke Kahanamoku, who is a Hawaiian swimmer who'd represented the United States in the Olympics, and you know someone who surfs, because surfing comes out of Polynesian culture. Obviously Duke Kahanamoku is touring Australia to sort of show off his swimming prowess but also spread the word about surfing and he does an exhibition surf at Freshwater Beach in the northern suburbs of Sydney and he decides to kind of add to the spectacle of this occasion that he'll invite a local girl from the crowd to do a tandem surf with him and so he pulls out Isabel Latham from the crowd and she becomes a kind of overnight celebrity.

26:26

The press kind of love this story of you know local beach girl on the board with the Duke and she's sort of hailed the freshwater mermaid. That's the kind of conventional story about Isabel that she sort of was the first woman to brave a surfboard. But I think what she did next is actually the more interesting part of it, because on the back of meeting these Americans and getting a taste for celebrity, she basically decides she wants to make her name in Hollywood. So she spends the next uh, three years she leaves school, she spends the next three years saving money to as a swimming teacher because she's not from a wealthy family, and saves up enough money for a one-way fare to go to California. At the age of 18, in 1918, when the war is still going, I sort of wonder what her parents thought of this. But she jumps on the ship and just kind of turns up in America thinking I'll just sort of, you know, connect with a few Australians in Hollywood and try and forge a career. And this, of course, is you know.

27:40

Her story in going to try and make her name in Hollywood is part of a broader story that's going on at this time. So many women from across Australia and across around the world are gravitating towards Hollywood, drawn by the kind of the promise of stardom, the promise of celebrity and the sense that there's a kind of feminised mass culture taking shape, that this is a kind of new form of cultural expression in which women can have a starring role. And what happens to Isabel next is also fairly typical, in that she, surprise, surprise, finds it harder than she expected to become a star. She gets a few kind of bit parts, but, you know, isn't the next Mary Pickford, and she also just like, like, doesn't really like acting, but then but she finds that she loves living in California, because why wouldn't she? You know, it's this period of intense migration of young people, particularly young women from all around the US and around the world coming into Los Angeles.

28:44

At this period. It's incredibly exciting. She's away from family, she's got freedom and anonymity and so she sort of finds ways to economically survive. Adjacent to Hollywood there's this historian, Hilary Hallett, who's written a book about this kind of period in Los Angeles and she uses the great phrase of pink collar industries, of these kind of feminized industries adjacent to Hollywood in which women can find work and, you know, have these kind of exciting independent lives. So Isabel finds work in one of the pink collar industries, which is hairdressing. It's also not something she loves, but it doesn't really matter because she is just so excited to be in California.

29:37

Then the next kind of phase of her story is she moves on to San Francisco and decides that she's had enough of hairdressing, but she wants to kind of draw on her athletic skills that she developed in Australia to try and forge a career as a swimming instructor, and she becomes known as one of San Francisco's leading swimming instructors at a time when there's a kind of growing interest in women's sport and the possibilities of using sport and swimming in particular to kind of craft a modern, streamlined athletic woman's body. And so she's very much at the cutting edge of these new cultural forces. And, interestingly, Isabel then tries to become one of the one of the many women in this study who not only are bringing American ideas back to Australia but are trying to import Australian ideas into the US. So Isabel of course has grown up in Sydney, which is around the time of the birth of Australian surf lifesaving, and she's very conscious there's no equivalent of surf lifesaving in California and that people are drowning on beaches when you know this could be eradicated. So she reaches out to the New South Wales surf lifesaving organisation and attempts to sort of get official endorsement from them to take their ideas to California and she's completely stonewalled because she's a woman. She's told very explicitly we do not teach ladies the work. You cannot get accreditation, you cannot, you know, have anything to do with, you know, representing us internationally. So Isabel finds this really confronting or frustrating, but also a sort of vindication of the narrative she's been building, which is that opportunities for women are higher in the United States. That's the quote she sort of says. And so, like so many of these women, she decides to make America her permanent home and takes out US citizenship because this sense that there's less hostility towards white professional women in California.

32:01

So Isabel is thriving in San Francisco in the late 1920s, she's living her best life and then calamity strikes. She's working as a swimming teacher at this very kind of glamorous, chic women's club that has a private pool, and she's walking home from work one evening along the streets of San Francisco and she falls into a manhole and breaks her back and can't work, doesn't have, you know, any kind of sick leave or insurance and is also supporting her mother by this time, who's her only surviving relative, her mother's living with her in San Francisco. So they decide to go back to Sydney because at least they still own a house in Sydney and they can, you know, stay there while she's recuperating from breaking her back. But then of course, like this is 1928, so we all know what happens after 1928. You know, the Great Depression strikes. She's, you know, struggling financially in Australia, then her mother's sick, then it's sort of World War II, so all these kind of sequence of events happen which means she can't get back to California and this is sort of a great tragedy of her life.

33:18

She reflects later in life that as soon as she got back to Sydney she realised she'd made a mistake and she felt stuck here and was desperate to get back but she couldn't. And this was a really, really common story that Australian women wanted to kind of live the rest of their life in America but because of sickness or, you know, accident, as in Isabel's case, or often because of the sickness or frailty of their parents, they were kind of forced, well, you know, induced, to come back to Australia prematurely and thinking it was often only going to be temporary, and would then, for various factors, kind of get stuck here and not be able to go home, not to go back to America. But the upshot of that in Isabel's case and in so many other cases, is that she then, like Mary Cecil Allen, is spreading American ideas in Australia, and in Isabel's case the big idea she's spreading is synchronised swimming. So she had.

34:20

You know, synchronised swimming kind of takes off in the US from the 1910s and 20s and Isabel is someone who's sort of in the cutting edge of women's swimming. Women's sport is very much exposed to this trend and so in Sydney she's teaching swimming again in the late 1940s and you know she starts one of the first synchronised swimming troops in the country. And you know she starts one of the first synchronised swimming troops in the country and you know very much styles it as an American sort of innovation. This is the time of Esther Williams kind of aquacade, synchronised swimming films, and Isabel is very much kind of emulating that sort of Hollywood look with the teenage girls she's teaching to do synchronised swimming in Sydney. So the coda to Isabel's story is not only that she introduced synchronised swimming but that she, you know, when women's surfing takes off in Australia in the 60s and 70s she sort of gets this recognition as a sort of founding mother of the sport and actually lives well into the 90s. She doesn't die until 1995 and lives in freshwater where she surfed first, learnt to surf that whole time.

35:38

But even though Duke Kahanamoku is very much kind of commemorated in the public landscape of fresh water and there's statues of him and all these plaques, Isabel is kind of still written out of that public heritage, which I think is quite unfortunate because you know, she's the Australian sort of figure in that story, sort of figure in that story. Now I might just talk about one other figure because I don't want to talk at you too long and I'd love to hear your questions and have a bigger conversation. Oh sorry, this is Isabel teaching swimming in San Francisco. It's her there on the left and actually I will just say one of the interesting dimensions about Isabel's teaching career in San Francisco is that these white Australian women went to the United States very much beholden to the narrative that the US was a fellow, you know, white man's country, to use the language that Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds use in drawing the global colour line.

36:46

So they kind of expected the level of Britishness and whiteness that existed in Australia in the early 20th century under the White Australia Policy, when the population was, you know, the non-Indigenous population was proclaimed as 98% British and that wasn't the case in the United States. It was actually, even though it, you know, did have increasingly racist, exclusionary immigration restriction that was modelled on white Australia. It did have a much more heterogeneous human population, you know, large migrant communities from China, from Japan, from Central and Eastern Europe and so on, and white Australian women were really confronted by this human diversity, which was very unlike what they'd experienced before. But they also found it often a really educational, eye-opening process. For many of them they would suggest this is the first time they had been in close contact with people they did not understand as white and that that had a kind of humanizing effect. So this was the case with Isabel that, in her capacity as a swimming teacher in San Francisco, she's, you know, working as a swimming teacher for the council and teaching quite a you know, large cross section of you know people from migrant communities in the city, and for her this is a moment in her life which makes her sort of, you know, deviate from an unquestioned acceptance of the logic of white Australia and begin to really see the benefits of multiculturalism and, you know, human diversity. And she brings those ideas back with her to Australia as well, and that's another very common narrative.

38:36

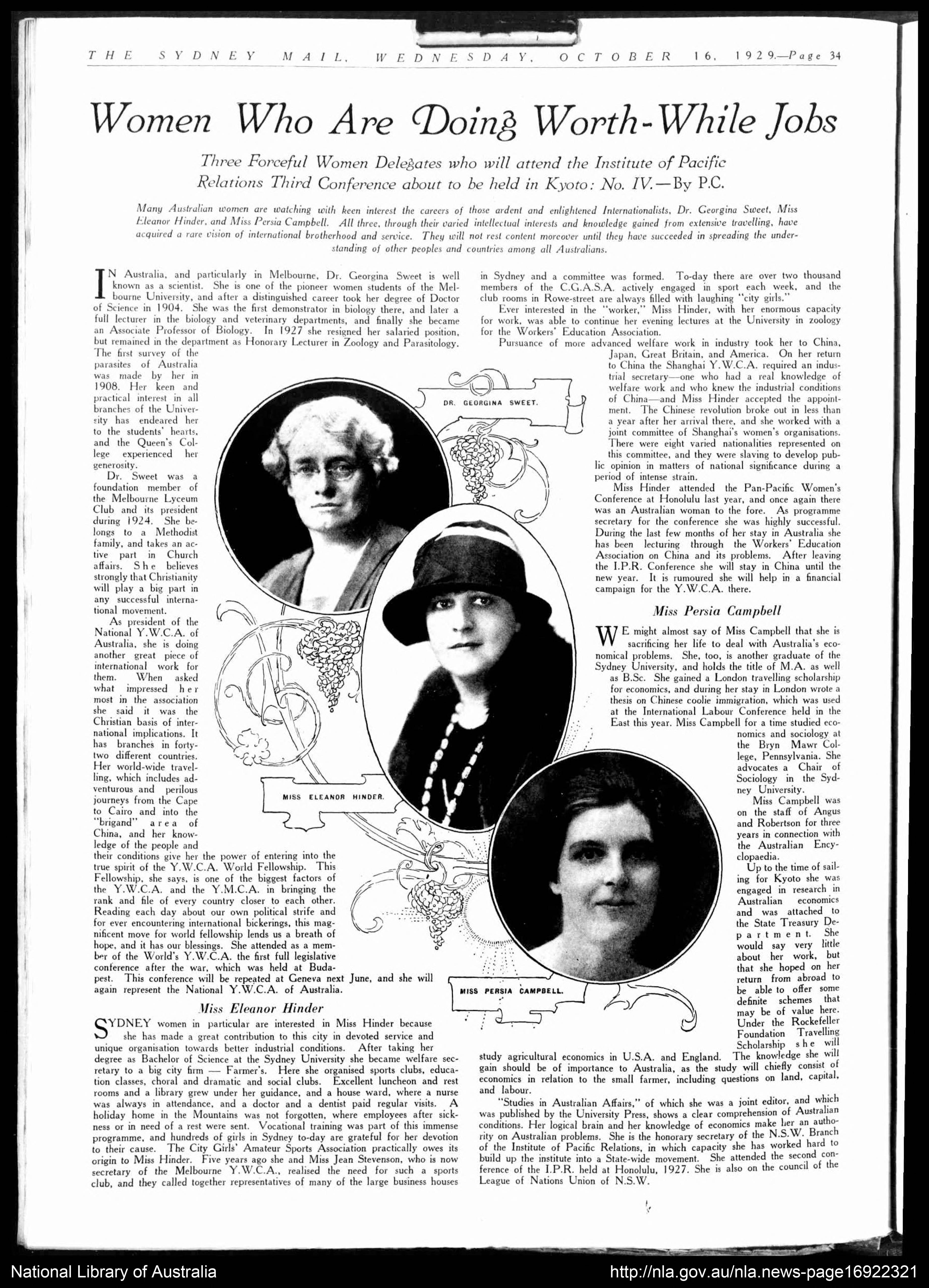

Okay, oh, and this is. This is the final woman I just wanted to share with you today, just out of interest. Has anyone heard of Persia Campbell? No, yeah, that's pretty standard and it's interesting because she is quite well remembered in the United States. So when I was over there researching her a number of years ago, I just was at a bar one evening and I got chatting to someone about my research and you know I mentioned Persia's name and this was a young man in his mid to late 20s who'd done an undergraduate economics degree and he said oh, of course, Persia Campbell. Yeah, I know all about her, yeah, we studied her at Uni and it's fascinating to me that she is kind of, you know, become part of a sort of canon of economic thought in the US but so incredibly forgotten in Australia, even though you know she was Australian and so many of her ideas which she's remembered for in the United States came out of the sort of economic thought of the Australian Federation moment. These were Australian, welfarist ideas that she took to America. So Persia Campbell was one of the first female economists in Australia.

40:05

She studies at the University of Sydney during World War I and she's sort of someone who is a humanitarian first and an economist second. She is studying at Sydney Uni during the war and is really horrified by the loss of life, by the suffering, you know, the humanitarian crisis of the Great War and this particular sense that so many of her male you know counterparts who should be studying alongside her are off dying on the battlefields. So she makes it her life mission to prevent another world war and in her thinking economic matters are kind of what drive international relations and fuel conflict between nations. So if you get the economics right you can stop war. So she studies economics at Sydney Uni at a time where this kind of idealistic model of economics, economics as a tool to sort of promote, you know, justice and harmony, is very much in vogue, and then later studies at the London School of Economics and at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania.

41:15

She gets a Rockefeller Fellowship in the late 1920s to do research in the United States and that sort of brings in another important part of this broader narrative, which is the role of American philanthropy in fueling this diaspora of Australian women to the US, very often Australian women who perhaps would have liked to study in London because it felt more culturally familiar and safe, were sort of nudged towards America by American money, because they're just the kind of cultures of private philanthropy and the way in which American philanthropy was sort of used as a weapon of or a tool of American internationalism and foreign policy in this period. Nothing like that existed in Britain, whereas in the US there's the Rockefeller Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, later the Fulbright scheme and a lot of other smaller bodies who are very explicitly in this period trying to draw the best and brightest of you know, young talent from Australia and around the world, draw them to study in the US to then essentially become, you know, boosters of the American superpower, to say that this is, you know, the future is in America and bring those ideas home with them. And Australian women were very caught up in this story and Persia was one of them. So she gets a Rockefeller fellowship as part of this kind of broader philanthropic movement, again only intends to stay in the US for about a year, but she falls in love and marries an American and then decides to make her home in the US and then she sort of becomes a leading figure in what's known as consumer economics. That's really flourishing in the 1930s in the US under the New Deal of Rockefeller.

43:20

Now, consumer economics I think it's one of those terms that it's easy to kind of understand as quite a trivial concept that you know consumer rights, you know individual consumer decisions, but what Persia understood it as is really a kind of radical feminist you know welfare-oriented inversion of conventional producers thinking about a capitalist economy. So she's sort of coming up to the conventional metrics for measuring economic success, such as gross domestic product, which are, all you know, based on production and output, and she's saying these are fundamentally flawed tools for measuring the health of the economy, because greater production doesn't actually tell us anything all that meaningful about how ordinary citizens and consumers are doing, about how their standard of living is going, whether they have much disposable income or not. So her vision of consumer economics is that we should measure the success of the economy of individual nations through looking at the living standards and consumption of individual consumers and households. So it's putting people's welfare and quality of life at the centre of measuring economic success. You know it's still within a capitalist framework, but within that it's much more welfare-oriented than a kind of GDP model. Persia becomes the leading proponent of these ideas in the United States. She writes a textbook on it, she becomes the nation's first consumer advisor to a government in the state of New York and then she also becomes a consumer economics advisor to President JFK in the 1960s and later to Lyndon Johnson after JFK's assassination.

45:26

And I guess the interesting thing about this is the seeds of Persia Campbell's consumer economics really come from the economic ideas in circulation in Australia when she was coming of age in the 1910s and 20s. This of course, this sort of federation moment in Australia, is of course a time when Australia is leading the world in terms of state interventions in the economic wellbeing of citizens, with things like the harvester judgment to inaugurate a living wage. And from her exposure to that kind of thinking this is where Persia gets the idea that you know, living standards should be at the heart of how economic, you know, success is measured. And so she sort of takes those ideas and runs with them and turns them into consumer economics and then throughout her career does repeatedly go back to Australia and try to kind of facilitate greater intellectual dialogue between the two countries. And he's repeatedly saying that you know, us economic thought has a lot to gain from Australia. She also has a very active career in the UN. She sort of has this whole other second life as an internationalist and sort of then takes these economic ideas to a global stage as well through her work in international development at the UN.

46:54

So there's many more women I could talk about, but I don't wanna keep you here all night. I would love to hear your questions. I suppose I just wanna close by suggesting that under conventional narratives of Australian history, the women I've discussed tonight and the other women in these books are peripheral figures. You know, they're transnational figures, they're women. They're, you know, globally outward looking. They're not, you know, involved in the kind of conventional canonical moments of Australian history, such as war and sport, that we use to define nation.

47:35

But I think there's an interesting way in which we can actually kind of flip the script and see someone like Persia Campbell as an archetypal Australian, because we know that Australians, you know there's a very large body of scholarship to show that Australians have always been some of the world's most enthusiastic travellers, always been highly transnational, highly engaged in the world.

47:59

So even though Australia kind of left sorry, Persia left Australia, she is a kind of exemplifying a typical Australianness in that way, and also because her humanitarianism, her welfarism, her commitment to doing good on the international stage, that is all very in keeping with the spirit of Australia's foundational federation moment, and that kind of the idealism of that moment was of course usurped by the sort of militaristic narrative of nation that emerged out of World War I. But I suppose I'm drawing on the thinking here of historians like Marilyn Lake and Claire Wright who said we can look back to that federation moment as a sort of alternative understanding of who we are as a settler nation. And if we follow that approach, Persia is actually a very typical Australian. So I would like to recenter her and the other women in this book in our national narratives. Thank you for listening.

Kate Follington Host

49:08

You've been listening to Dr Yves Rees sharing the life stories of artist Mary Cecil Allen, judge May Lay, swim instructor Isabel Lethem and economist Persia Campbell. This is another episode of Look History in the Eye, the podcast of Public Record Office, Victoria. Thank you.

00:00 / 49:47