Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

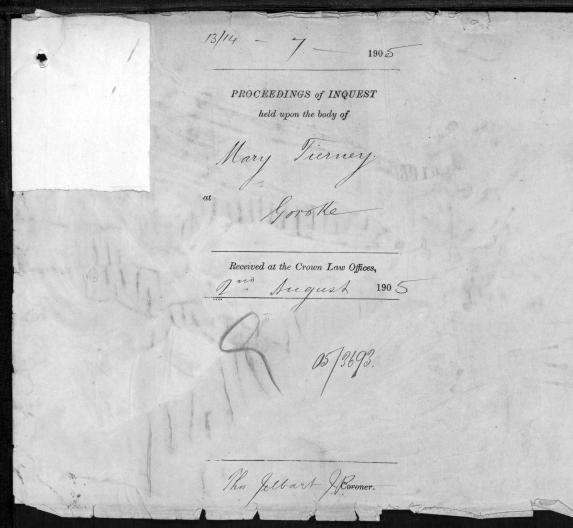

The following is a short story of historical fiction inspired by the 1905 inquest of Mrs Tierney. The original record (linked below) provides the crux of the story, with creative license used to fill in the gaps. This was written to display one of the ways in which the archives can inspire creative writing, outside of straight non-fiction.

Inquests are particularly fascinating, yet emotional, records to delve into, as are criminal trial briefs and even divorce records. Our photographic collections are a fantastic resource for visual representations of Victoria’s past.

Please note that as this story relates to an inquest case it may be upsetting for some readers.

On to the story

Mrs Tierney crept out of bed to the sound of the crows. She tiptoed across creaking floorboards, careful not to wake Mary, still snoring down the hall. Her white night gown swept dust from the ground beneath her, as she walked barefoot across the farmstead to the kitchen. Her sunken belly growled and gurgled. The kitchen door hung open, her new husband and his farmhand Russell having been in for breakfast earlier, before ploughing the paddock. The peas she’d set to soak the night before bobbed in their watery bowl on the table, left over apple tart from last night sat nearby, calling out to her.

Thick, slightly browned crust cradled apples and sugar. Her stomach sang loudly as she took a spoon from the cabinet. Too hungry to find a clean bowl, she sat and dug straight in, gobbling three mouthfuls before the bitter taste hit her. She coughed and sipped on the pea water before taking a closer look at the pastry before her. It was darker than last night. Had the damp, late autumn air infected it? She leant down, nose close to the table, and sniffed. It smelled fine. She tried another mouthful and almost fell off her chair. She composed herself as her husband, Will Tierney, appeared at the door. She cringed, embarrassed to have made such a terrible tasting tart for his friends.

‘Morning,’ he said, kicking off his boots and taking a break by the wood fire. The sharp smell of his woolen socks swirled throughout the room.

‘What’s that face for?’ he asked.

She sighed at her failure. They hadn’t been married long. New wife, can’t clean, can’t cook.

‘The tart has a horrid, vile taste,’ she admitted, holding out her spoon.

Maybe it wasn’t as bad as she thought, her taste buds affected by the smoke of last night’s tobacco.

He came towards her, leant down placing his hand over hers. They spoon fed him together. He spat the tart out immediately. Crumbs landed on her nightgown. She hadn’t even dressed yet. Had hoped to be in and out of the kitchen before anyone saw her. Another failure.

‘You must have put something in it. Alum or acid or something,’ he said.

‘Why would I do that?’ she said. ‘I hope it didn’t taste like this last night. Mr Neeson did not taste it like this.’

‘Nobody would eat it if it tasted like that,’ he said.

She blinked back tears. He was right. Surely her husband’s friends would not have polished off their slices had the tart been bitter last night. If only she hadn’t been so busy playing hostess, he too busy playing cards, they'd have tried it themselves.

‘Must have been sitting out too long,’ she said, he nodded as she changed subject ‘I thought you may have visited my room last night after the party.’

‘I was exhausted,’ he said as he fussed about the kitchen. He sipped some water, snuck a fresh pea, pulled his boots on, and went back to work. The stench of his socks lingered as she whispered after him.

‘You’re always exhausted.’

She stayed seated, staring at the tart. Tried one more bite, like her husband, spitting it out.

‘Morning.’ Mary entered then. Before Mrs Tierney married, Mary had lived and worked at Mr Tierney’s home. Caring for his elderly mother as she passed, cleaning and cooking – more edible feasts than this. This was Mary’s first visit back to the farmstead since leaving Mr Tierney’s employ.

‘Something wrong with the tart?’ Mary asked, readying a pot of tea for the stove as though she still worked there.

‘It’s terrible,’ Mrs Tierney said. She stood, dusting the crumbs and sugar from her nightgown. She thought she saw Mary smile. ‘Don’t try it,’ she warned her.

‘How about some tea then? I’ll wash some cups and saucers while you get dressed,’ Mary said.

‘You don’t have to do that, you’re a guest,’ Mrs Tierney said.

Mary explained she wanted to make herself useful. Mrs Tierney felt anything but, in her new marital home.

‘Alright. But I’d like to make Will’s morning tea and take it out to him,’ Mrs Tierney said.

Venturing back across the farmstead to her room, she dodged salamanders and ants on the cracked ground beneath her feet. She regretted not slipping boots on that morning, her desire not to wake Mary trumping practicality. She dressed quickly, her stomach still grumbling, mouth watering for tea. Her husband and the farmhand’s laughter carried across the paddock through her bedroom window. She peered out and saw Mary taking them water and scones. She’d wanted to do that.

Mrs Tierney slouched on the corner of her bed and wept. Why was it so easy for Mary? Why did other women have no trouble cooking and cleaning and keeping a home? She had waited for marriage, longer than other girls, fearing this very outcome. She belonged in town, in a classroom with her students. But she wanted to belong here, on the farm, with him. A man so many women had coveted, and she’d won. Why couldn’t she get anything else right? Not even a simple tart.

Back in the kitchen she tied an apron round her waist as Mary poured them both tea. They sat together by the fire, knees curled under their dresses. Mrs Tierney tasted acid on the lip of her cup. She shook her head. The taste must have remained on her tongue from earlier. She held her breath and took a large sip. Then another, trying to get past the bitterness. The same as before. She watched Mary, watching her.

‘Something wrong?’

‘Have you had a sip yet?’ Mrs Tierney asked.

‘Too hot,’ Mary said.

‘Let me know once you’ve taken a sip. I must be going mad. Everything tastes so bitter this morning. I can’t stomach it.’ She took her cup back out to the kitchen trough. Her spoon and plates from the previous night were submerged in grey dish water.

‘Did you wash the teacups and pot in here? You didn’t have to do that, you should have left it for me,’ Mrs Tierney said, her back turned to Mary, she dipped her fingers in the dirty water.

‘I don’t mind. I washed them all together. Gosh Mrs Tierney you’re right, it tastes awful.’ Mary approached from behind, throwing the contents of her cup out the door.

‘You had a sip?’

‘Yes, when you came in here. Awful.’

Mrs Tierney looked around the kitchen. Canister of flour, tea, vegetables, everything appeared to be how she’d left it. The tart still sitting in its place. Flowers wilting in a vase on the bench. Even the dust on the cupboards she’d kept forgetting to clean remained undisturbed.

‘Are you feeling alright Mrs Tierney?’

She wasn’t imagining things, was she? Her husband tasted the tart too. Now Mary tasted bitter tea. It wasn’t just her.

‘I’ll fetch some other cups and saucers, see if that helps.’

Mrs Tierney burst outside, taking in desperate gulps of fresh farm air. She went into the small living space off the main farmstead, emptying the cabinet of her husband’s family tea set. Blue petals adorned the pearlescent pottery cups. A silver teapot that didn’t match the set. She placed them on a tray held close to her chest, careful not to drop any on her journey back to the kitchen.

‘Here we are,’ she told Mary. ‘Let’s try fresh cups and pot.’

The biting taste was gone. They drank their tea by the fire and speculated between them whether the tart-laden cutlery tainted the dish water, or the water itself was bad. Mary paused their conversation every so often to ask Mrs Tierney if she was feeling alright.

‘Just embarrassed, I think. My first dinner party as a married woman and I’m terrified all the food was as bad as it was this morning. I wish I’d had time to eat last night, try it before serving it to all of Will’s friends.’

‘I can assure you it was lovely,’ Mary said.

They sat in comfortable silence, Mary’s reassurance putting Mrs Tierney’s mind at ease. Then Mrs Tierney felt a familiar sensation, sore muscles, head spinning, wild racing thoughts. She remembered the sharp taste of her water the day of a recent dance. She and her friends had joked that someone must have tried to poison her. Bitter taste of poison in the water.

‘He’ll think I’m mad,’ Mrs Tierney broke the silence.

‘Who?’

‘My husband. Both the tart and tea taste off. It’s just odd.’

‘Do you want to talk to him about it?’ Mary asked.

Mrs Tierney stood ‘Yes.’ She took Mary’s hand, and they went into the chill air, across the paddock, towards her husband and his farmhand, Russell.

‘Sowing potatoes?’ she asked as they approached.

‘Picking,’ Mr Tierney said. Of course, she couldn’t even get that right.

‘My word, the ground will plough nice here. It is a pity all the paddock is not like that,’ Mrs Tierney said, trying to sound knowledgeable, kicking at the dirt. Mary stood back, behind her, watching.

‘Wasn’t that tart horridly bitter this morning,’ Mrs Tierney said.

‘It was terrible altogether.’ Mr Tierney bent down to pick loose potatoes up, throwing them in Russell’s direction.

‘We had some tea since and that was bitter too.’

He laughed. ‘Ok, now you’re making yourself frightened. You're making yourself believe everything is bitter. You’ll make yourself sick.’

Russell chuckled to himself, moving further away to continue picking. She was sure she could feel Mary smile behind her. But she didn’t know why. Couldn’t understand why they’d all tasted it too yet only she was frightened. Making herself believe everything to be bitter.

‘No, no,’ she said. ‘The tea was bitter too, so we left the big house and got the little silver teapot and other cups and made some tea and that was alright. It might account for the other tea being bitter, if some of the water was soaking cutlery with leftover tart, it might have got to the other cups.’

Mr Tierney shook his head. ‘Why don’t you go for a walk, settle your nerves?’

Mrs Tierney rolled her eyes, leant up to kiss her husband on the forehead and motioned to Mary. ‘Come on then Mary, I knew what he’d say, didn’t I?’

Mary clasped Mrs Tierney’s hand as they walked through the marram grass along the edge of the farmstead. Mrs Tierney grasped tighter with each step, trying to push down the sensation of nausea and achy muscles.

‘Perhaps we should go inside Mrs Tierney, you don’t seem well.’

‘I’m fine. He’s probably right, just making myself sick. Paranoia not poison.’

‘Poison? Who said anything about poison?’ Mary said.

‘Nothing, never mind. Let’s go in. I’ve got potatoes to wash, and you have a book to lose yourself in, no doubt.’

Mrs Tierney didn’t want her husband to think she could only keep house with Mary’s help. She would prove him, and herself, wrong. She’d be more careful from now on. Careful not to leave baked goods out overnight, to wash dishes separately, to taste everything before she served it. This would be a lesson to her.

She washed potatoes, drained peas, wiped hands dry on her apron. Her head felt light, her muscles sorer than before. The sound of whinnies as Mr Tierney passed the kitchen door towards the horse shed caught her off guard. She reached for a chair but fell to the floor with a thud, billows of flour and salt surrounding her.

‘What in the world has happened to you?’ Mr Tierney ran in, crouching by his wife’s side.

Mrs Tierney couldn’t answer. Her mouth now dry. Words stuck in her throat. Mr Tierney helped her onto the chair and pressed again.

‘You sick dear?’

‘Yes,’ she sputtered. Immediately thinking of the tart, the tea, the bitterness. ‘Are you alright? Is Mary alright?’

‘I’m fine,’ he said.

‘Oh, Will, I am all smashed up, falling to pieces.’

‘You’ll be alright, sit here. I’ll go check on Mary.’ He brushed her arm with his rough, dirty hands, leaving her for his old servant.

Mrs Tierney listened as he called. She thought she heard him cry for Mary, Mary say she had been sick but was better now. Mary and Will entered the kitchen with a tin of Epsom salts.

‘Thought you might need this,’ said Mary. ‘I know you like to take salts when sick.’

‘Yes, yes, alright.’

Mary prepared some salts for Mrs Tierney while Mr Tierney watched on. The salts themselves were bitter, bought on some retching, and more pain. She did not throw up the tart or tea. All sat mingled in her stomach. Bloated now. Between spasms she watched as Mary and her husband debated throwing the tart to the pigs. Russell came by and suggested a doctor in town, then called for the ponies. Mr Tierney and Mary bundled Mrs Tierney up in the buggy and off to Natimuk they rode. They passed wet landscape, greens, yellows and oranges. Kangaroos chased them into town. Something about the bumpy, quiet ride, the cool air on her face, settled Mrs Tierney’s stomach.

‘You’re not going to believe this,’ she said to Mary and her husband. ‘But I’m feeling a little better.’

They waited at the local hotel for the doctor anyway, apologising for dragging him away from his Agricultural and Pastoral Society meeting. He saw Mrs Tierney in a private room, but before he could close the door behind him, Mr Tierney and Mary followed them in. Mrs Tierney felt nervous then. Nervous to be laughed at a second time by her husband. To watch Mary smile as she speculated about water and tarts and tea and, dare she say, poison. She clammed up at the doctor’s probing.

‘What’s the matter then, not feeling well Mrs Tierney? I heard you had a lovely dinner party last night, a bit worse for wear, are we?’

She sat on the hotel bed, looking over to her husband and friend as they stood in the doorway.

‘No nothing like that,’ she said. ‘Will, Mary, would you mind leaving me with the doctor a moment and fetch me some water?’

They nodded and left. She sighed relief as she described the symptoms that came on after consuming the tart and tea. She suggested a sample of the tart be tested.

‘Can you do that?’

‘I can if you have some to give me. You can bring it to me tomorrow at my home. You’re feeling better now though? It may just have been a case of common food poisoning, now passed over.’

‘I’m feeling better so that must be it,’ she said. But she still wanted to the tart tested.

‘I’ll speak to your husband about fetching some of the tart and delivering it to me tomorrow.’ The doctor gave Mrs Tierney a quick once over, a hand to her forehead, a look in her eyes.

‘Yes, fine now,’ he said. He gave her some medicine to help her nerves and suggested she eat something. Before leaving her bedside he stopped short.

‘Any poison in the home?’

‘My husband keeps strychnine for the mice.’

The doctor nodded and turned from her, hiding his concerned eyes.

‘Make sure your husband brings me some of that tart.’

Upon returning home from Natimuk, her husband gave her more salts to ease remaining symptoms. Mary fetched her more tea. She felt worse again. Bitterness, acid, gravel, was all Mrs Tierney could taste in everything she drank and ate. Twitching muscles, sweats, weakness.

Russell wouldn’t look her in the eye, making himself scarce he skinned a dead sheep up the road, returning hands bloody.

Mrs Tierney asked Mr Tierney to take some tart to the doctor. Her requests drowned out by coughs and fits and a husband who wouldn’t listen.

She loved the farmstead. The sound of the horses, the pigs, the smells of grass and the beauty of the paddocks. So different from her lovely little classroom, but beautiful all the same. She knew she was dying, insisting on being taken out to the verandah to see it all one last time. Her husband held her. She’d been poisoned she knew. She looked between her husband and Mary. In the distance, the fences and cows of the neighbours, smoke curling from their chimneys. The farmhouse and kitchen were always unlocked. Many farmhands, not just Russell, came and went. Her mind raced. The bitter tart, the tea, the salts. She’d only been a wife a short time, and she’d been so bad at it. So wrong about everything. But right about this.

‘I feel weak,’ she said. Her last words. Bitter through gritted teeth. The taste of tart and tea still on her tongue. An empty bottle of Strychnine sat still in the cupboard.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples