Author: Kate Follington

Please note the proceeding text describes records related to illness and death and may be upsetting for some readers.

Emma Williams and her brother Edward were riding their horses back from Sale, regional Victoria, cantering along Maffra Road outside the Turf Hotel, when Emma was hit by another coughing fit. She tried desperately to stifle it, pushing a handkerchief into her mouth not to draw attention to herself, but it did little. Edward jumped off his horse and pulled them both over to the fence so he could help Emma dismount, before seating her gently on the ground. By then blood was dribbling from her nose and she whispered for water, Edward ran to get help nearby, but looking back he saw Emma cry out, clasping her hands together against her face as blood now covered her mouth and dress, she fell down sideways onto the road. Emma died moments later while her brother wiped her face with water and a neighbour gently cradled her away.

It was 1872 and Consumption Tuberculosis (TB), also called the white plague, was robbing the world of its youth, and in Emma’s case, a ruptured blood vessel of the lung made hers a memorable departure.

Tuberculosis was Australia's leading cause of death

Tuberculosis (TB) was Australia’s leading cause of death by the 20th Century and poor urban settings were its preferred playground; overcrowded living conditions were, and still are, an ideal backdrop for the contagion to spread. Clinging to human droplets thrown into the air, the advantageous bacteria bounced from one happy host to another, laying dormant in most people’s lungs, while ravaging the life force out of the weak and unwell, leaving them pale, wasted away and dying slowly. As it destroyed their lung tissue, leaving behind large cavities or lesions, the live bacteria was then coughed up in spits of blood, which can survive hours in the right conditions.

From Emma’s death in 1872 it took another eighty years to produce a cure. Treatment for the disease was scarce and mostly ineffective until the 1950s. Avoiding TB had a massive long term impact on modern living, because during the discovery for a cure a whole new way of thinking emerged about how to build public and private spaces to reduce its spread, which could be both curative and functional. Inquest records of TB victims, like the one described above of Emma Williams, indicate that patients were sick and contagious for at least three or more years so they needed to be quarantined for long stretches of time, and their living conditions influenced heavily on their survival.

During the discovery for a cure a whole new way of thinking emerged about how to build public and private spaces which could be both curative and functional.

The accepted treatment plan by the early 1900s, in the absence of anything better was to send TB patients to sun drenched sanatoriums in the mountains, to a moderate dry climate for rest and a nutritious diet. The movement began in Europe and gained plenty of momentum when early stage patients indeed recovered, their immune systems emboldened with some much needed rest and relaxation. Those who were too sick however were quickly sent back home to die.

The power of heliotherapy and the sanatorium era

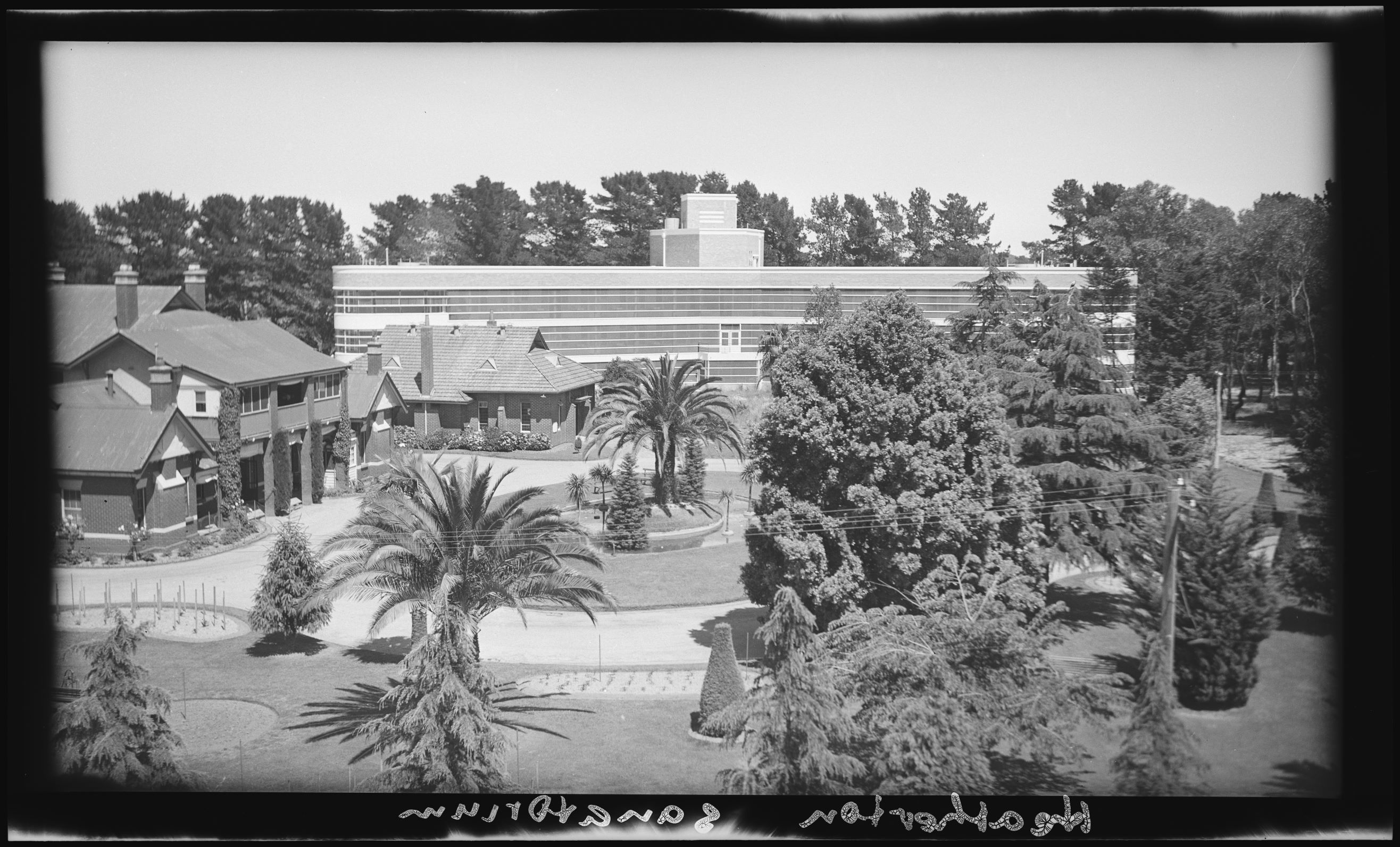

Public Record Office Victoria has digitised a series of photographs originally produced by the Department of Public Works from 1926 until 1965, which includes the era of sanatorium construction under modernist architect Percy Everett.

By the 1920s modernist architects found a sympathetic bedfellow in the medical establishment, both groups recommended an end to dark and dusty ornamental spaces, and instead emphasised functional surfaces that are easy to clean; this was not only a better way of living, but an imperative to reduce a global pandemic.

Doctors were also validating modernist design ideas and post war youth, unlike their ‘peaches and cream’ mothers, happily followed their sage advice to become trendy Sun-Tan Girls:

‘You see her every day now, on the beach, out on the open road, on the river, wherever there's sunlight. She’s the Sun-tan Girl, the typical bronzed Australian. A modern miss with modern and perfectly correct ideas about the value of fresh air and sunshine.’ (Adelaide Advertiser Dec. 1929)

Heliotherapy, or the healing power of light, gained tremendous traction after 1900. The medical journal The Practitioner, claimed in 1901 that the TB bacteria could survive in dust for a long time but in sunlight it would die in just a few weeks. A popular catchphrase according to medical historian Margaret Campbell was ‘Thirty years in the dark, thirty seconds in the sun’.

Australia responded to this hypothesis in a desperate attempt to stop the spread of the disease. The Victorian Government built Greenvale Sanatorium in 1905 consisting of seven canvas lined timber huts with plenty of outside seating, and then built Heatherton Sanatorium in 1913.

Despite the appeal of lounging about for a year these were designed to be quiet ‘no fun’ places: Greenvale Sanatorium even had a rules sheet:

‘The congregating of patients is conducive to over-excitement, excessive talking, or laughing, all of which is injurious to damaged lungs. Singing is forbidden, as are also dancing, and the playing of wind instruments. Only unexciting literature is allowed in the Sanatorium…’

Curative design emboldens Europe's modernist architects

By the late 1920s Europe’s bold young architects were setting a new bar for curative Sanatorium design. They designed them with leafy outlooks, flat roofs and open decks for air flow or sunbathing, with large glass windows for lounging beside all day.

Architectural historian Professor Julie Willis described this era as a ‘confluence of health and modern architecture, treatment and design’. In her paper Health of Architecture she delved into the travel notes of Australian hospital architect Arthur Stephenson who wrote his reaction in 1932 to the radical TB sanatorium Zonnestraal, in the Netherlands:

‘From the traditional forms of old buildings you swing to extreme originality of thought as exemplified in the now famous Zonnestraal Hospital which is constructed almost entirely of glass. This [is a] beautiful institution…’ (Arthur Stephenson,1932)

Percy Everett's influence on light filled schools and hospitals

Percy Everett, took over The Department of Public Works in Victoria in 1934 and had visited Europe in 1930 and then the United States in 1945. It’s very likely he was inspired by European curative design ideas given how much rounded glass featured in his school and sanatorium designs.

On his return from America he hosted the inaugural State Architects Conference in 1946 and in his chairman’s summary, he noted the positive feedback he’d received on his Solar Control System applied across schools and sanatoriums. In short, with the right projection at roof level the sun is shaded in summer but allowed to enter in winter. He also liked high clerestory windows, capturing daylight even if the lower building was surrounded by shade.

By 1946 Tuberculosis was killing a third of Australians aged between 20 and 40

By 1946 TB was responsible for the death of a third of Australians aged between 20 and 40, and so the Commonwealth injected $54,000 pounds towards new sanatoriums, doubling the bed numbers in Victoria. Everett’s enthusiasm for capturing seasonal light could then be fully justified as curative design, so at Heatherton he built a massive three-storey glass boomerang-shaped wing with an internal auditorium for projecting films for patient entertainment.

Large additions were added to Greenvale Sanatorium and Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. Smaller 14 bed chalets began to dot the landscape across regional Victoria, and a good example was Everett’s Hamilton chalet which was perhaps his most whimsical with a playful nautical touch, an opportunistic nod to classic ‘30s Streamline Moderne (what a shame it was abandoned so soon when various drug treatments offered a cure by the late 50s.)

When retiring in 1953, a journalist wrote of Everett’s ultimate legacy, and despite his reputation it was not in fact his Art Deco entrance to the Melbourne Zoo, or the Russell Street Police Headquarters geometric stepped skyscraper, it was in fact his belief in the healing power of light for public buildings.

‘The black holes and the dark corners, which were used too often as places of punishment for children, were given notice to quit. Light replaced dark-ness!’ (Argus, 1953).

This article was originally published in 2021 as The Modernist Touch on TB for Traces Magazine October, 2021

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples