Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

In the new exhibition ‘Melbourne: Foundations of a City’ at Old Treasury Building, presented in partnership with Public Record Office Victoria, we learn what it was like to work in the city in the mid-1800s.

Men at work

In the nineteenth century Melbourne, men worked in a wide range of occupations with names now unfamiliar. Tanners, fellmongers, tallow-makers and slaughtermen were all clustered along the banks of the Yarra. On the wharves, navies, boatmen and lightermen loaded and unloaded cargos, while an army of carters moved goods further afield. Horses generated a host of specialist workers – grooms, stable hands, ostlers, horse breakers, cab men, coachmen, coach and carriage makers, saddle makers, blacksmiths, and at the bottom of the heap the orderly or ‘scoop-boy’.

Women at work

The opportunities for women were more limited and mostly poorly paid. Increasingly women sought escape from domestic occupations by working in factories or shops. The clothing industry clustered in Flinders Lane employed many women in small workshops. Still more worked from home as outworkers paid by the piece in trades commonly referred to as ‘sweating’, from the poor rate of pay. Women with a little capital could become publicans or keep boarding houses. An educated woman might keep a school. Towards the end of the century women began to benefit from the new occupations as they trained as type writers and telephonists, gradually replacing men. They also trained as nurses and teachers.

Here we delve a little deeper into a few of the occupations mentioned in the exhibition:

Fellmongers

Fellmongers dealt in fells or sheepskins, separating the wool from the pelts. As the work required water, for soaking, fellmongers were located alongside the Yarra River with wool washers and tanners. The name fellmonger was derived from Old English meaning for skins (fell) and dealer (monger). In a letter to the editor of The Age 22 Sept 1896, the wife of a fellmonger described the demands of the profession:

“The writer says her husband earns 5s. 6d. for a day for 10 hours, and his is the best pay in the firm… fellmongers have frequently to return to work after tea for two or three hours, and occasionally they toil all night, making a total of 20 hours’ consecutive work. Sundays and holidays they must also be in attendance.”

Lightermen

Lightermen unloaded cargo from ships, bringing it into port via flat-bottomed barges known as ‘lighters’. To be a lighterman you had to be an “experienced seaman, of good physique, capable of handling ship’s tackle and gear and of assisting in the control of small craft when under tow and in the moving of such craft,” according to a job ad in The Argus, Sat 18 June 1955.

This article from The Argus explains a little about what the life of a lighterman was like in the early 20th century.

Scoop-boys

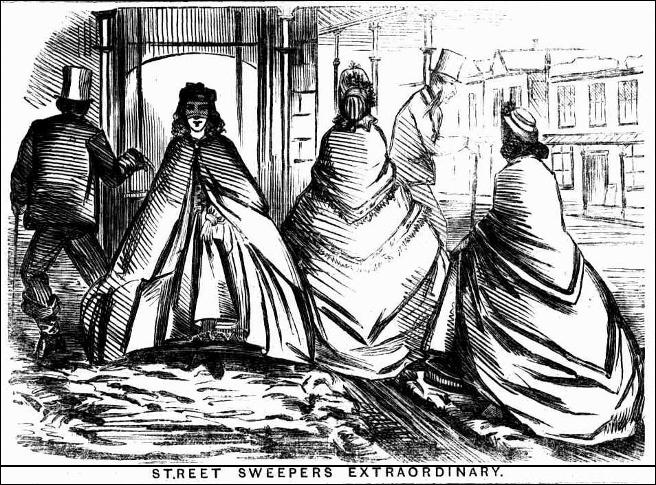

Scoop boys were a group of young workers, between the ages of 14 and 18, employed by the City Council to clear Melbourne streets of horse manure and other litter. Street sweepers were also employed to clear dust and rubbish and hose down footpaths. These were dangerous jobs whereby the scoop boys and street sweepers would often have to weave between traffic on the busy streets.

Telephonists

Before the introduction of automated telephone exchanges in Melbourne from 1914, telephonists were employed to patch callers through to each other. Telephonists were overwhelmingly women. A reporter for The Argus described a visit to the Melbourne Telephone Exchange in 1886:

I went “into the ladies’ chamber, the central sun from which radiating rays now permeate the commercial world of Melbourne – a lofty, roomy, well-lighted, well-ventilated, and (in this wintry weather) well warmed apartment, where, before a huge brass-plated screen, hole riddled, like a gigantic solitaire board, with counterweighted wires hanging thickly over its face, stood about a dozen young ladies, all absorbingly engaged as if tuning a Brobdingnagian piano, or playing some novel form of cribbage on a stupendous scale. As they stepped lightly a pace or so right and left, pegging away in the multitudinous holes, connecting, disconnecting, receiving and replying to the messages of the unseen subscribers scattered here and there throughout the city.”

References other than the Old Treasury exhibition:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fellmonger

https://www.history.ac.uk/gh/water.htm

https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/rubbish-catalogue.pdf

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples