Author: Jelena Gvozdic

Researching a non-government institution at PROV

PROV (Public Record Office Victoria) does not collect the records of non-government organisations; it does however hold series of correspondence files created by a number of major Victorian government agencies. Many of these agencies file documents on a range of activities, including the government’s interaction with non-government organisations. This showcase will take a look at a non-denominational institution established in 1857 to care for and reform “fallen women” – the Carlton Female Refuge.

This site is “a rare surviving example of an early social welfare institution devoted to the welfare of women and children...and other institutions [established] on the site illustrate changes in attitudes to women and sexuality since its foundation” (National Trust, p.1).

The main building as it stood after its closure in 1997

Origins and aims of a charitable institution

Female refuges, where 'unchaste' women were confined in the hope that they could be converted and reformed, had been established throughout the Western world from 1758 with the opening of London’s Magdalen Hospital. Historians have traced the evolution of such refuges from as early as 1257 with the establishment of the Convertite Santa Maria Maddalena Penitente in Florence. The first such institution in colonial Victoria, however, was Melbourne’s Carlton Refuge. Its original site was on Madeline (now Swanston) Street but in 1890 the institution moved to Keppell Street, Carlton, where it would operate until its closure in 1949.

The Refuge was guided by Protestant ideals and came about in a time in Victoria’s history where poverty was common place. Increased unemployment created hardship for many and the influx of immigrants from the 1850s meant that many “friendless” young girls were arriving into the state when work was scarce. They found themselves excluded from reputable employment, with no family to turn to for assistance. Many took to the streets and young women in Victoria were, subsequently, engaging in prostitution or crime. Others found themselves in situations where they were pregnant and unmarried, poor, and shunned by society and often by their own families. Within this social setting the strength of the evangelical movement was prominent, many charitable institutions were established throughout the state to combat this social “problem”.

Restoring public morality

prosperous family who have migrated to one of the colonies (“Here and There”, Punch Magazine, 1848).

Central to the Refuge’s efforts was the aim to reform public morality by housing and reforming these individuals - a meeting of the committee of the Refuge in 1860 explains that they were: “animated simply by the desire to rescue from degradation and ruin as many abandoned and unfortunate women as might be desirous of retracing their steps and of returning to habits of decency and virtue (The Age, 20 March 1860, p.6). The Government Gazette, which shows the petition to have the Refuge incorporated under the Hospitals and Charities Act 1890, clearly states that the objectives of the institution “are the reception, care-taking, education, and reformation of females who, previously to their becoming inmates, have led an irregular and abandoned life, or who have been living as common prostitutes” (July 5, 1895 p.2568). Eventually, the primary clientele would become single mothers and their infants, who as well as prostitutes, were still treated as “ruined” having strayed from the moral expectations of the time. This shift of having pregnant women as the main inmates, was definitely evident later in the 20th century, in the improvements of the building, the references to maternal and child health welfare, and the eventual abandonment of religious aims.

A case study by the Heritage Council of Victoria identifies a framework of three distinct, historical stages of the Carlton Refuge Keppell Street site – how these stages are reflected in some corresponding PROV records will be discussed below.

Reform and penitence 1860-c.1900

From its opening in 1860-c.1900 the theme of reform and penitence is prevalent especially in the presence of the Chapel (pictured to the right). We know from a pamphlet book published in 1919, which details the early history of the Refuge, that the original building on Keppell Street had an imposing brick wall and a number of cell-like rooms.

The Vice President of the Ladies’ Committee M. J. Kernot describes it as “altogether a most prison-like place” where the girls, “peeping from their narrow windows, could see the high brick wall whichever way they looked” (1919 p.4).

As recent observers have noted, although the Refuge provided some kind of support, these women were ostracized by the majority of society and refused assistance by their families, with their only means of aid in a site which essentially operated like a prison. Once admitted they were confined behind high walls for 12 months, treated as “fallen”, subjected to “religious injunctions to repent of their sin, and contributed through their labour to the work of the home” (Swain 2014 p.17). The institution was supported not only by voluntary contributions but by the income derived from the work done by the inmates in the laundry. Some young women were sent to the Refuge as an alternative to a fixed term of imprisonment or after having been picked up by police, while others were dispatched by their parents/carers or other institutions. Newspaper reports indicate as much – Louisa Johnston was charged with vagrancy and stealing, the former ex-industrial school girl was discharged to the Refuge in 1880 after a representative offered to obtain her admission; in 1899 Bella Baker, aged 24, was the informant in a case of desertion, she fell pregnant, having been seduced “under promise of marriage”, and went to the Refuge after giving birth to the child at the Women’s Hospital; Mary Rose Evans, 15 years of age, was admitted in 1892, after having been examined at the Women’s Hospital on suspicions that illegal instruments and drugs were used to terminate her pregnancy – her mother had admitted her to the house where the operations were allegedly taking place.

Criminal Case Records

Criminal case records, inquests and police correspondence can offer a window into discovering the background of those who made their way to the refuge, as well as how the institution operated.

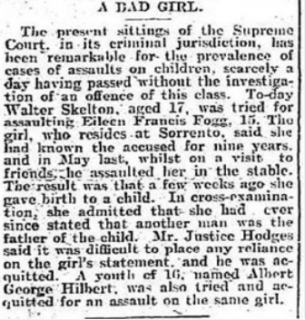

There is the case of Eileen Francis Fogg, admitted on the 7th March 1906, with the baby she had given birth to at age 15 only a month prior. Eileen brought charges against three youths for sexually assaulting her, believing one to be the father of the child. All three were found not guilty as the judge said it was “difficult to place any reliance” on her statements (VPRS 30/P0/1411 Case 22; VPRS 30/P0/1412 Case 33 & VPRS 30/P0/1412 Case 34). It appears that Eileen was transferred after the Refuge accepted the decision made by the magistrate in her final case against the accused youths. By 1909 the annual report of the Refuge mentioned that a “deplorable” feature was that “the great majority of the women admitted were not of the profligate class, but were girl mothers…[and] the unfortunate part of the matter was that the men who were responsible for the trouble went scathless.” (Kalgoorlie Western Argus, 3 August 1909, p.30).

Victoria Police 1906 report for the inquest of Eileen's baby.

Whether or not Eileen had made false charges against these boys, her life would be struck by tragedy two months after being admitted. Her baby passed away at the site, at only three months of age. An inquest was held into the death and it was found that there were no suspicious circumstances – Eileen had awoken one morning to find her baby had suffocated after having gone to sleep with her in her arm. Mrs. Thompson, head Matron, gave a deposition for the inquest stating that Eileen was a “particularly kind and attentive mother” and that inmates were aware of the necessity to use the cots provided for them in their sleeping quarters (VPRS 24/P0/800, 1906/419). Mothers would often take their infants into their own beds when nurses weren’t by - many infant deaths of this sort took place in private homes, in other institutions, like the Women’s Hospital, as well as the Carlton Refuge.

From the 1890s the police were responsible for inspecting institutions exempt from the Infant Life Protection Act of 1890, in order to compile returns and particulars related to the care of infants. This Act was established to register and supervise the women whom mothers would pay to look after their infants - while they worked to earn enough money to support themselves, and their child/children. In the case of the Carlton Refuge, infants were kept with mothers for some time, between 4-12 months. If a situation couldn’t be obtained where a mother could have her child with her, the baby would be boarded out to a suitable person, as selected by the Matron. If a mother was unable to earn enough to keep herself and the child, then the baby would be adopted or made a ward of the state. There would have been instances where the Refuge organized to have girls sent to suitable homes to work as domestic servants, taking their babies with them. Elizabeth Dobson, for example, had left the Refuge with her baby in 1892; she was a domestic servant in the employ of Madame Bartel, having obtained herself a situation so she could regularly support her child. She would be charged in 1893, however, with abandoning her baby in a street - her employer described her as trustworthy and honest “but she seemed to be bowed down with grief, or always very despondent” (Oakleigh Leader, 15 April 1893 p.5). Find & Connect explains that the “social stigma surrounding illegitimacy was a factor behind many children being relinquished by unmarried mothers, or being placed in out-of-home 'care'… attitudes to children born from ex-nuptial pregnancies [only] started to shift from around the 1960s in Australia”.

Police correspondence noted that the refuge would have nothing to do with a child from the time it leaves the institution (VPRS 937/P0/348). They found that this state of affairs did “not appear to be satisfactory” and “unless some provision in this direction can be made [that the children are supervised after their leaving the institution], it will be necessary that all persons receiving infants from the Refuge shall register under Section 4 of the Act” (Letter from Inspecting Superintendent Thomas, 28th June 1893, ibid). A change was made in 1893 after the Matron and the Ladies Committee came to an agreement with the police to have all the infants, which were boarded out, returned to the Refuge once a month for inspection (Victoria Police Report July 6th 1893, ibid).

A changing emphasis: the care of women and their babies

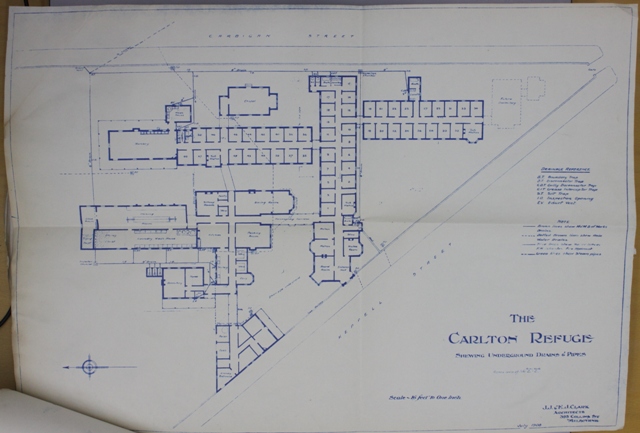

Circa 1900-1949 there is a changing emphasis, the traditional focus upon reforming sinful women through religious instruction and hard work is unappealing and the new approach to the care of women and their children is instead reflected. In celebrating the Refuge’s jubilee in 1904, it was decided that the building would be improved upon.

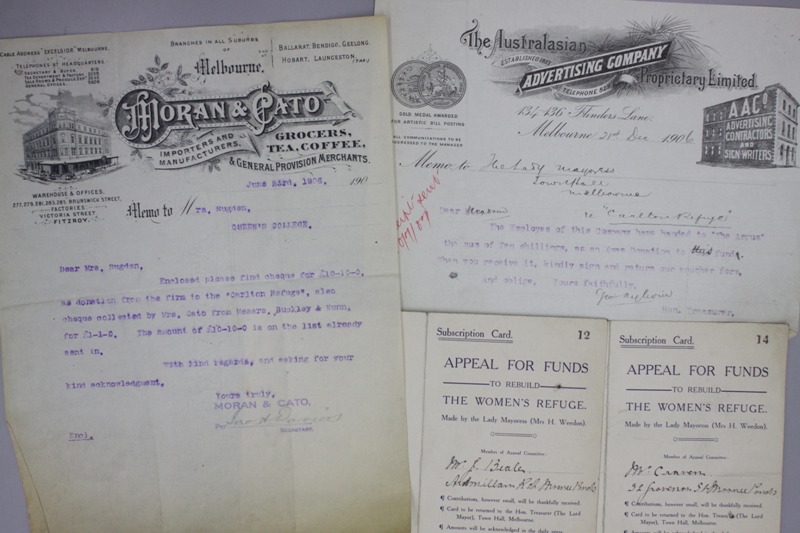

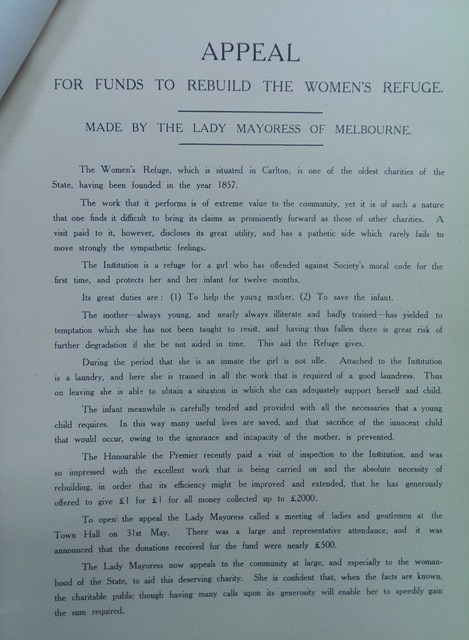

This unit (VPRS 3183/P0/40 Carlton Women's Refuge Charity, Relief & Health 1906-1907) contains particulars relating to the Carlton Refuge Building Fund, launched from 1904 to raise funds for new buildings on the site. Lady Mayoress of Melbourne, Fanny Weedon, was instrumental in raising support for these improvements and the governor also promised to match one pound for each pound. In the end some 4500 pounds was raised - the new buildings would open in May 1907, with the laying of a foundation stone by Mrs. Weedon. The fund’s cash book and account with the Commercial Bank of Australia Limited is located within the unit. As are the letters which accompanied the cheques and subscription cards sent by the public, in support of the fund.

Many expressed the cause to be a deserving charity which helped young mothers and their infants. We can also find the signed letters forwarded by Fanny to Victorian officials asking for aid, as well as her appeal pamphlets. In the appeal she states that the institution cares for girls who have “offended against Society’s moral code” and its great duties are “(1) To help the young mother, (2) To save the infant” as they are “carefully tended and provided with all the necessaries that a young child requires” (VPRS 3183/P0/40). The mother “always young…has yielded to temptation which she has not been taught to resist, and having thus fallen there is great risk of further degradation if she be not aided in time” (ibid). The unmarried mothers are clearly still regarded as fallen women.

The new works included the building of new dormitory wings, which had smaller, more private rooms, with large windows and good ventilation, a far cry from the small cell-like sleeping quarters, with narrow slots for windows. The nursery was also significantly improved upon, with verandahs on all sides so the babies could receive the benefits of fresh air. These changes “anticipated the development of the maternal and child health movement that was to begin after World War I” (Heritage Council of Victoria 2010).

Corresponding with the Hospitals and Charities Commission

PROV holds various correspondence papers between the Refuge and the Charities Board of Victoria and its successor the Hospitals and Charities Commission (VPRS 4523/P1/54 File 503 (1923-1934) & VPRS 4523/P1/148 File 1441 (1934-1952).

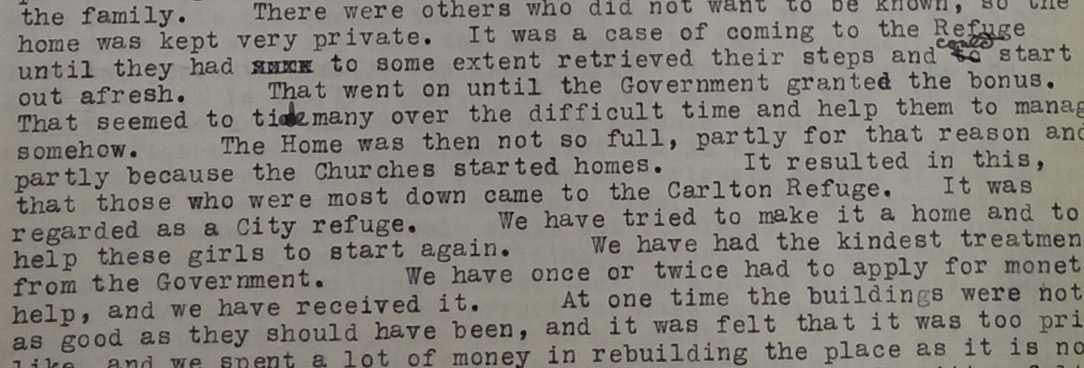

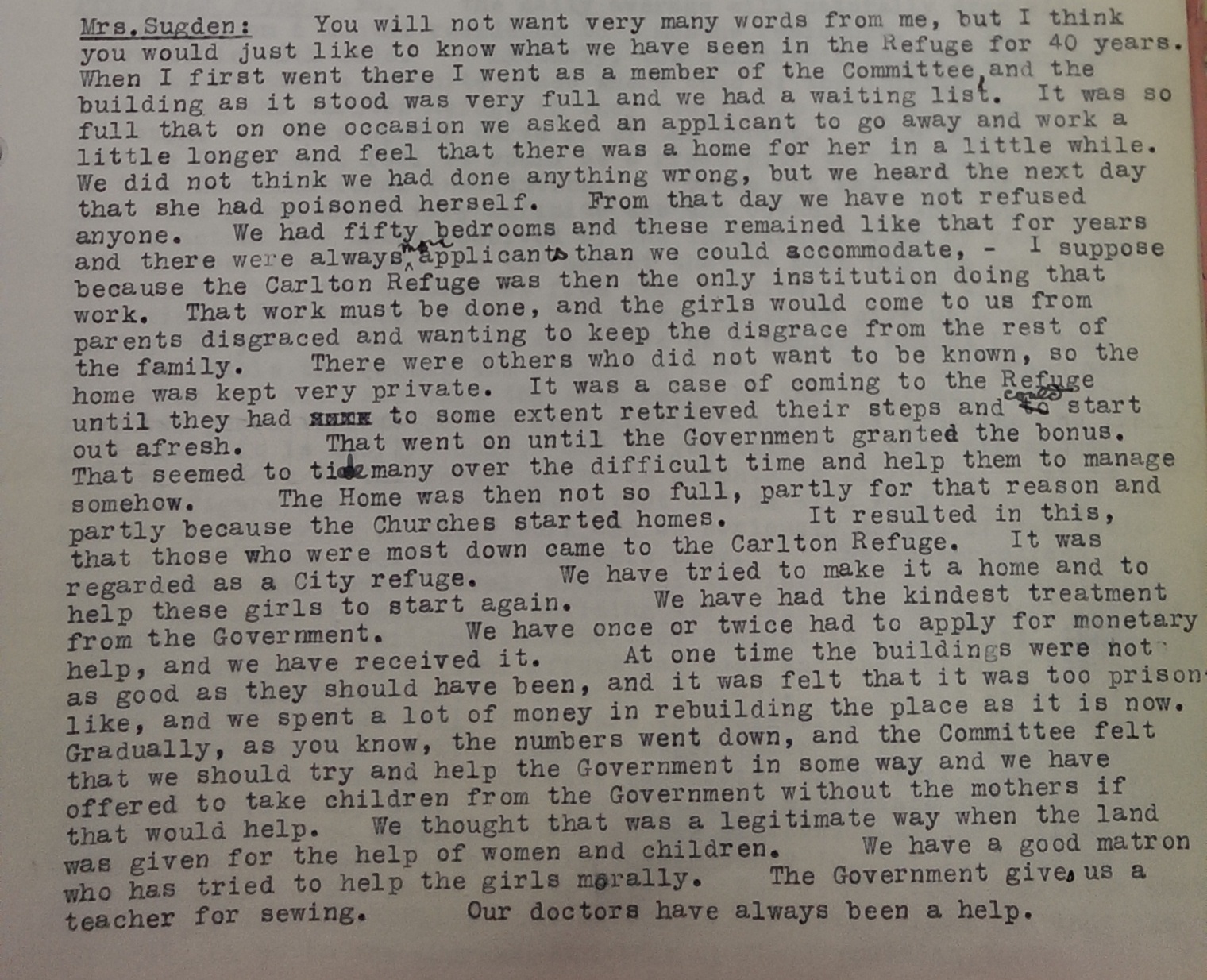

In this series are two sets of files which provide insight into the administration of the site, the grants and requests lodged by the Refuge’s Committee, and the continuing social stigma attached to sexually active, unmarried women. In a request to the Board for further financial assistance, dated 30th May 1935, the work of the Refuge is described as the “reclamation of fallen girls in and over the period of motherhood and the necessary early care of childhood” (File 1441). We can also see the extended efforts the Refuge made to help the Women’s Hospital, as well as the Children’s Welfare Department, by caring for infants under the latter’s care, and providing supervision and care to mothers awaiting entrance to the hospital. There was discussion to change the name of the Refuge given this supplementary work, and that “reputable” married pregnant women may be averse to staying in such an institution. The name was changed to the “Carlton Home” in 1930. There are notes of the 1930 joint committee of the Carlton Refuge and the Metropolitan Standing Committee, set up to discuss the concern that the overall site wasn't put to good use. During this time period, fewer inmates were being admitted. Mrs. Sudgen, who appears to have been part of the institution for 40 years, gives a telling outline of the circumstances of many arrivals - “the girls would come to us from parents disgraced and wanting to keep the disgrace from the rest of the family...there were others who did not want to be known, so the home was kept very private” (Conference Notes 22nd May 1930, File 503, see image below).

Historical sources do state that the “great desire of the [Refuge] committee is to keep mother and child together” (Kernot 1919, p.7). Nonetheless, government inquiries and apologies have highlighted the role of government and non-government organizations in forced adoptions and the plight of single or unmarried mothers well into the 20th century.

A model Baby Health Centre 1951-1997 closure

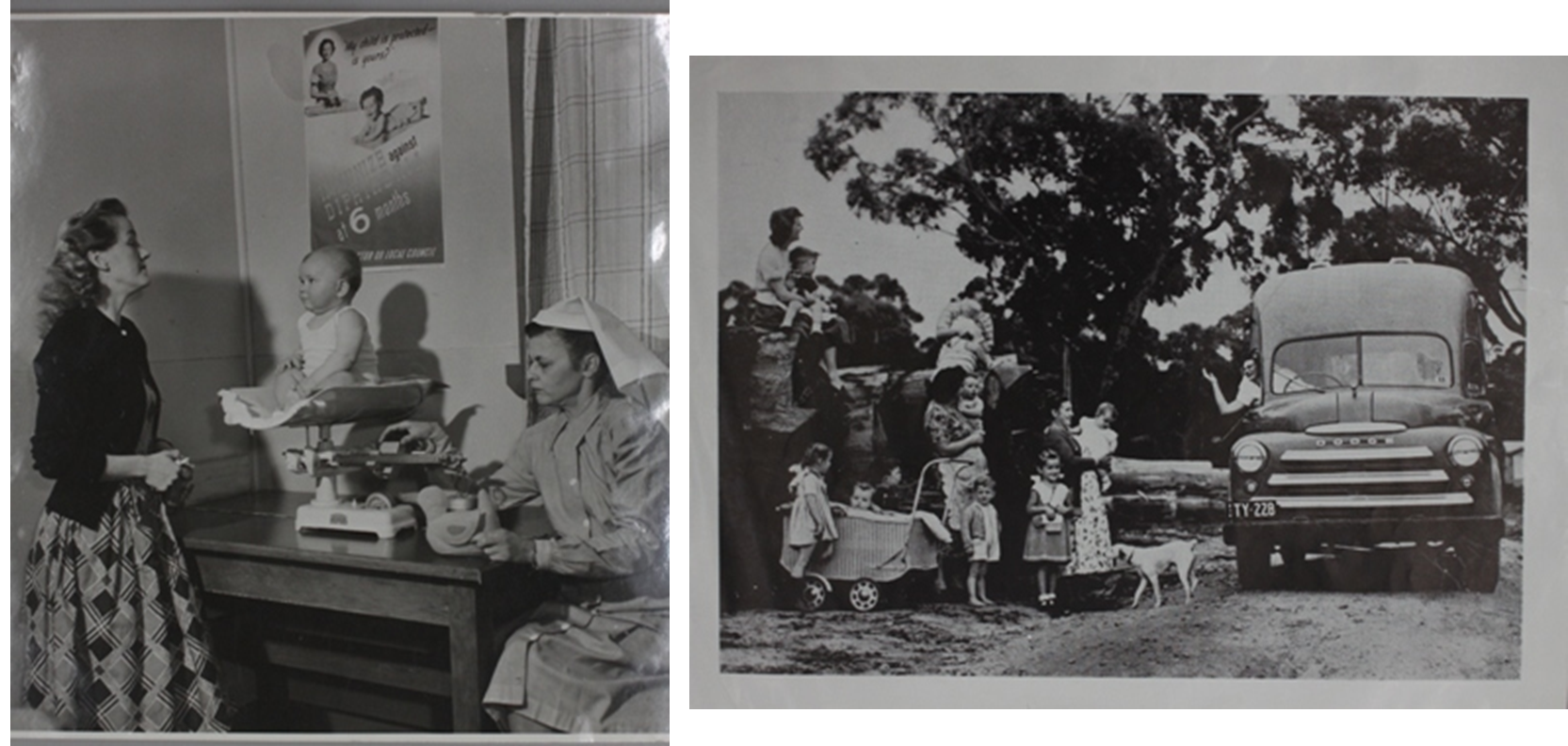

Finally from 1951 onwards the site was a model for maternal and child health, religious associations had ceased and the design of the building was typical of Baby Health Centres of the post-war era.

This file (VPRS 6345/P0/112 File 622/1 Proposed Maternal and Infant Welfare Centre) contains government correspondence documenting the closure of the Carlton Refuge and the decisions leading up to having the site become the home of the Queen Elizabeth Maternal and Child Health Centre and Infants Hospital (opened in 1951- functioned as such until 1997). By this time this was a specialised site providing health services for women, married and unmarried, and their young children.

PROV recently accessioned a collection of records relating to the Maternal and Child Health Service (Infant Welfare), which began in Victoria in 1917. One such series is a photographic collection, VPRS 16682, which records aspects of the Infant Welfare Service including centre-based, home-based and rural work, children's institutions, and the involvement of State and Local Governments, for example, through the official openings of infant welfare centres.

The fundamental role of the Keppell Street site as providing services for women and children is a common thread throughout its history. The philosophy associated with the aims of the different institutions which operated on the site, definitely changed, as is noted in the Heritage Council's case study of the site. The religious rhetoric eventually faded as health services for women and children came to the forefront. Find & Connect summarizes that “while the institution focused on the 'care' of mothers, it is evident that the Refuge also accommodated some babies and children after their mothers were discharged” and “the historical sources contain many references to the Refuge's approach of encouraging unmarried mothers to keep their babies if possible”. As heritage experts explain, this was a complex and layered site, which we can learn even more about by looking through official government records and newspaper accounts. It is very closely connected to the early history of social welfare, the contribution of Protestant churches to charitable work in Victoria, and the experience of unwed mothers in the social and religious context of 19th and 20th century Melbourne. No doubt there are more records to be discovered in PROV’s collection after some thorough research. It has been said that a fire destroyed most of the Refuge’s early official records but a manuscript collection is held by the State Library of Victoria, accession number MS 10952, which includes: minutes (1882-1949); receipts (1921-1943); expenditures (1919-1943); visitors' book (1903-1948) (includes records of baptisms 1931-1938 and marriages 1936-1937); annual reports (1944-1945 and 1948); and insurance policies (1875-1943).

Sources

Find & Connect, “Carlton Refuge (1854 - 1949)”, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/vic/E000601

Heritage Council of Victoria 2010, “Case Study 1: Queen Elizabeth Centre”, Framework of Historical Themes Part 2, pp.44-45

Kernot, M. J. 1919, Reminiscences of the Carlton Refuge, 1854 to 1919, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/130478

Law, A (with) Grimsham, P, “Family Situations in Carlton”, in Among the terraces: Carlton's parks and pastimes, Carlton Forest Project, North Carlton, Vic, http://www.unimelb.edu.au/infoserv/lee/htm/family_support.htm

National Trust, “Former Carlton Refuge (Queen Elizabeth Maternal & Child Care Health Centre)”, http://vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au/#detail_places;65172

Swain S 2014, History of institutions providing out-of-home residential care for children, Australian Catholic University

Wickham D 2003, “Beyond the Wall: Ballarat Female Refuge, a Case Study in Moral Authority”, Master’s Thesis, Australian Catholic University

Dr. Christine A Cole’s doctoral thesis “Stolen Babies - Broken Hearts: Forced Adoption in Australia 1881-1987” contextualizes the historical experience of unwed mothers in colonial and 20th century Australia, it is available for viewing on the following link: http://forcedadoptions.naa.gov.au/content/stolen-babies-broken-hearts-forced-adoption-australia-1881-1987

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples