Author: Jan Harkin

Writer, researcher

An ancestor with an unusual name is a boon for a family history researcher but it comes with a caution. Cross-checking for accuracy is essential.

Some of my searches of the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) catalogue, for example, revealed stories that turned out to be about someone other than the ancestor I was seeking.

Isabella deaths

My two-times great-grandmother was Isabella Foster McLean. PROV’s archives include one will of an Isabella Foster McLean. She lived in St Kilda and died in November 1911, less than a month after signing her will with “her mark” because she was too ill to write her name. The PROV file reveals that her executor - her daughter Lenore – later moved to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, taking her mother’s grand piano with her.

That wasn’t my Isabella. My Isabella Foster McLean died in December 1921, while visiting her lawyer’s office at “Oxford Chambers, Melbourne” (Argus, Melbourne, 14 December 1921, p. 1).

Attempts to find out if an autopsy occurred after my grandmother’s death produced a similar result. My grandmother died in hospital in 1940 when my father was twelve-years-old. He knew little about her. He thought her name was Peggie or Margaret. PROV searches revealed she was born Isabella Margaret but her marriage and death certificates included alternative spellings – Isabel and Isobel.

I searched PROV’s legal records using all three spellings. The search turned up one court document, dated eight months after her death. Could this be a court case about the medical treatment she received?

The first document in the file stated that Isobel Margaret Davis of East St Kilda was charged with “unlawfully using an instrument with intent to procure a miscarriage”. She was found “not guilty” and discharged. The documents also stated that the same woman had been previously convicted of being in possession of morphine without authority.

My grandmother had never lived in East St Kilda but to be certain that this Isobel was not my grandmother, I searched TROVE for reports of the case. These showed clearly that the woman charged was still alive in December 1941 and could not be my grandmother.

This was not the last time that her name made the Melbourne newspapers. In 1948, the Victorian Coroner found Isobel Margaret Davis, 40, had died as a result of strangulation. He ordered barman Reginald Gilford Mann to stand trial charged with her murder. Mann was tried three times over the death of his de-facto wife Isobel, who was also known as “Nurse Duff”. The juries in the first two trials could not agree on a verdict. The third jury acquitted him of the murder charge but found him guilty of manslaughter. He was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment (Herald, 13 April, 16 June, 22 September 1948; The Age, 14 April, 18 June, 26 August, 23 September, 1948; The Argus, 14 April, 17 June, 18 June, 26 August, 1948).

I have found no record of an inquest into my grandmother’s death and no evidence that she left a will.

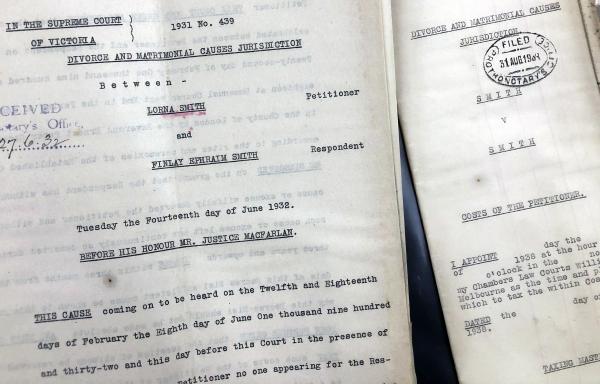

Lorna’s divorce

Searching for information about my mother’s side of the family proved more fruitful. PROV records revealed that my great uncle Perc’s wife, Lorna, had been divorced before they married. Lorna had kept a diary all her adult life. Unsurprisingly, the PROV divorce records included her detailed account of her first marriage and the reasons she was seeking a divorce.

Lorna had given me a blank diary for Christmas when I was about eight-years-old and gave me one of hers to read. She had worked as a housekeeper at one of the grand houses in Toorak. Perc was one of the gardeners. The diary Lorna allowed me to read told of the night Mr Robert Menzies came to dinner. Word came down to Lorna in the kitchen that Mr Menzies had admired Perc’s roses. Perc accepted the compliment but ignored Lorna’s suggestion that he should cut some roses for Mr Menzies’ wife, Patty.

Perc was a Labour man; Mr Menzies was leader of the other lot. He would have to pick his own roses.

The divorce records at PROV revealed that Lorna’s first husband was Finlay Ephraim Smith. The unusual name helped me to check details from Lorna’s divorce petition, including addresses, dates of birth and her husband’s army record.

Lorna Streader met and married the man she called “Fin” in London in 1918, during World War I. She was a twenty-three-year-old Londoner; Fin was an Australian soldier, aged 32. Lorna lived in Hampstead with her mother and sister and worked as a laundress. Fin was a farrier with the Australian Army Service Corps. His army records confirmed that the Staff Sergeant served at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. His service records states that he had “an exemplary record” during his war service, “suffered nothing abroad and complains of nothing now”, except “possibly some dental issue that was being treated”. He had “no entries” for punishments and his character was “very good”. He had been mentioned in Sir Douglas Haig’s despatch on 7 April, 1918 for “conspicuous services rendered” (Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No. 165, 14 October 1918; London Gazette, 28 May 1918).

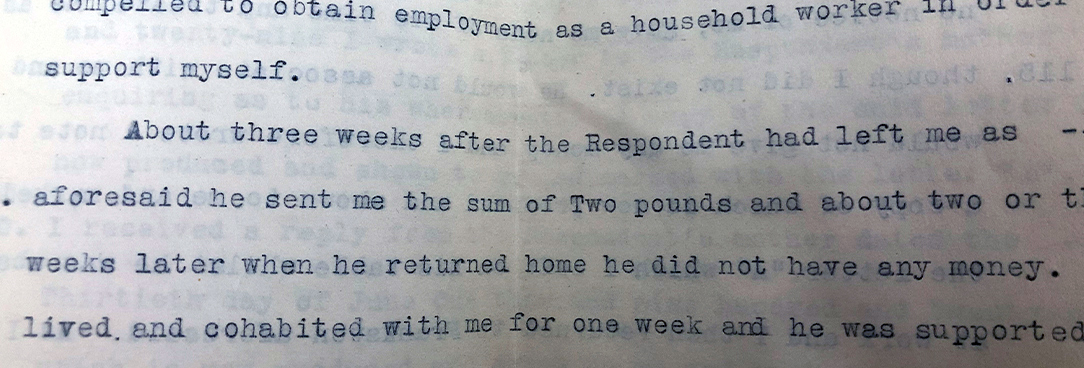

The couple lived together in Australia after the war but the world had changed. Lorna documented her husband’s difficulties finding work as a farrier or labourer. She told how he “commenced going out at night and not returning until a late hour” and added that “frequently when he returned he was under the influence of liquor”. She explained that:

“At this time as the Respondent was not allowing me sufficient money for housekeeping expenses I was unable to pay the trades people and when I asked him to increase his allowance he abused me.”

Fin left her to “go lumping wheat in the country” in January 1922. Destitute, she found employment “as a household worker” to support herself. In March he told her to sell up everything and he would send for her to come and live with him in “Springhurst in the state of Victoria”. When she arrived, he sent her to a boarding house owned by “a Mrs Kelly”, where he came for meals, but he continued to live in a hut nearby. When he heard that she had sold their things as instructed but used most of the money to pay their creditors, including outstanding rent, he became hostile.

“He took no notice of me, gave me none of his time and treated me as though I did not exist.”

Lorna had no money. Fin gave her none. Two weeks after she arrived at Springhurst, she borrowed her train fare from Mrs Kelly and returned to Frankston, leaving a “box containing my personal belongings as a security for payment” for her board and lodging. She also left a letter for Fin.

“You go your way and I’ll go mine as I feel sure you do not want me,” she wrote, signing the letter “Your brokenhearted wife Lorna”.

Back in Frankston, Lorna found work as a domestic at a boarding house to support herself. Later that year she heard that Fin had returned to Frankston but his family did not know where he was living. She did not see or hear from Fin again and filed for divorce on 2 December 1931.

Court efforts to locate Fin proved fruitless. He did not respond to notices in The Age and The Argus newspapers stating that Lorna had commenced proceedings in the Supreme Court of Victoria for a divorce on the grounds of desertion “for three years and upwards”. The case proceeded in his absence. The divorce was granted in 1932 and reported in The Argus (15 June, 1932, p. 15). Later that year, she married Perc.

The PROV records show that Lorna was charged £18-11-1 for legal costs of the divorce.

Newspaper searches on the TROVE website fleshed out further details. They revealed that Fin was assaulted and robbed in Adelaide in 1933 (Barrier Miner, Broken Hill, Monday 10 April 1933, p. 3). He had fallen asleep on a bed after a heavy bout of drinking with a couple he met in a pub. The couple were committed for trial for stealing £23 from his trousers pocket. Fin died in Deniliquin in 1941, aged 57 years (Standard, Frankston, 12 September 1941, p. 4).

Lorna and Perc’s wills

Reading Lorna’s story reminded me of visits to the two-room cottage in Mornington where Lorna and Perc lived after retiring from working in Melbourne. Lorna kept a row of glass jars where she placed money from their pension for rent, utilities and other expenses to ensure she could pay all her bills as they fell due. Lorna and Perc’s wills, part of the PROV archives, showed they left no debts. Lorna died at Mornington on 1 January 1974. Perc died twelve days’ later. Their doctor told me that Perc died of a broken heart. He could not face life without his beloved Lorna and simply pined away.

The combination of PROV searches and trawling through TROVE filled out the gaps, revealing the strength and resilience of a stoic woman.

About the author

Jan Harkin completed a PhD in journalism at Monash University in 2021 while attending Hazel Edwards’ “Complete Your Book in a Year” course at the Victorian Archives Centre. The PhD included the non-fiction book Older Drivers: Mobility, Ageing and Fitness to Drive, which was written and workshopped during Hazel’s classes. It also included an exegesis: Older Drivers in Australia: Supporting Safe Driving through book-length journalism.

Jan’s latest historical project – Dancing in the Rain – is based on her father’s experiences as a young teen growing up in Melbourne without parents during World War II.

PROV records mentioned throughout this article include

- Lorna's divorce record: VPRS 283/P0002, 1931/439

- Lorna's will: VPRS 7591/P0004 776/009

- Perc's probate: VPRS 28/P0007 776/008

- Isobel case file: VPRS 17020/P0003 Dec 1942 / 19

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples