Author: Natasha Cantwell

Communications & Public Programming Officer

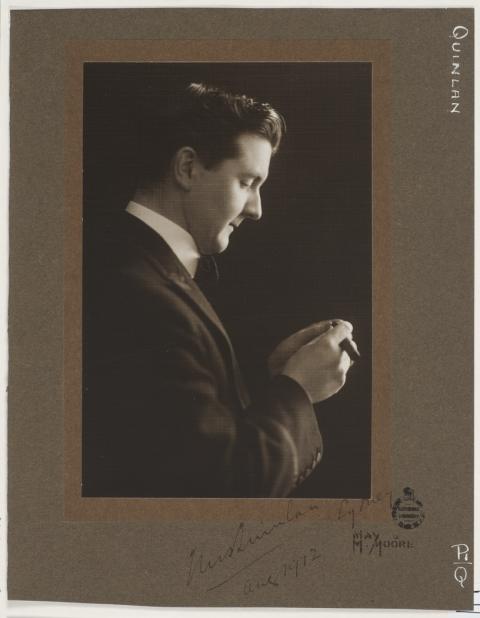

British impresario Thomas Quinlan was well-known in the 1910s for bringing ambitious, large-scale opera productions to the colonies. He formed the Quinlan Opera Company in 1911, with the dream that music fans across the UK, Canada, South Africa and Australia would be able to experience the kind of grand operas that were previously only performed at Covent Garden.

The company toured the world, staging hugely successful orchestral and choral shows until their 1922 Australian tour by the Sistine Chapel Choir turned out to be a financial failure. What happened to Quinlan after this disastrous last tour? The only information Wikipedia has on Quinlan after this date is that he was divorced from his wife Dora in 1926 and then died in 1951. To discover more, you need to dig a little deeper, as the answer lies in a place you wouldn’t expect - the hand written clinical notes from Melbourne’s Kew Asylum.

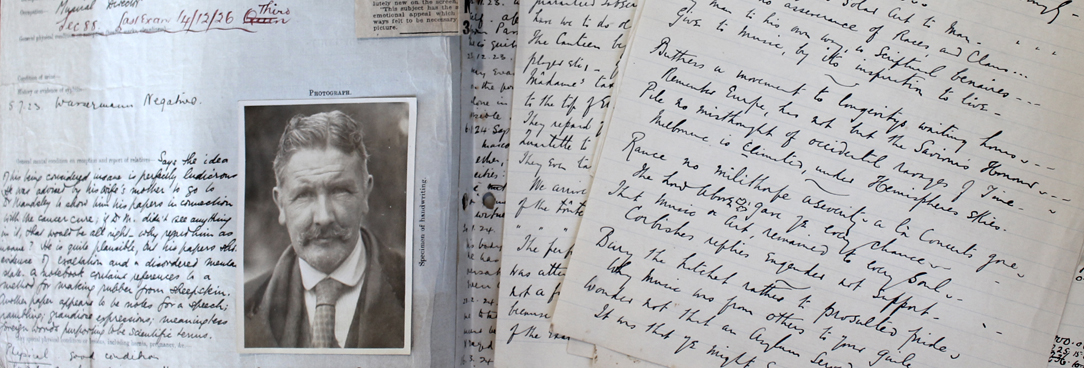

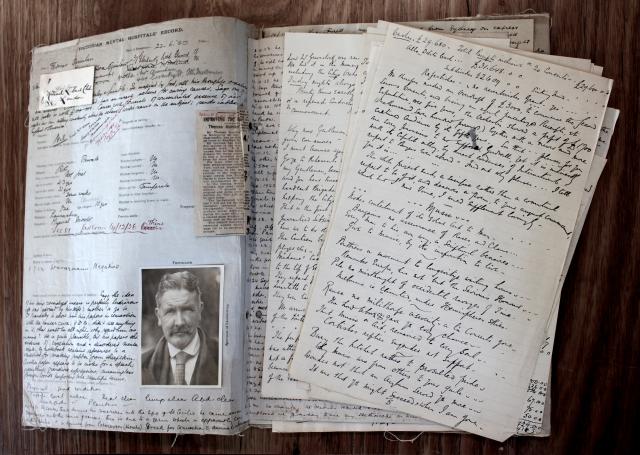

According to his patient file, by December 1922 Quinlan was “in an emotional state, crying, praying and physically ill.” It was at this point that he turned his back on opera to focus on the world of science. A local newspaper clipping attached to his record (The Herald, 2 June 1923) reports that “it is not generally known that he has been a student of Science for many years. Music to him was a diversion and a relaxation from more serious studies.” In the article Quinlan makes bold claims about his scientific breakthroughs in the world of cinema and music recording, including a “double photographic lens” that would enable movie cameras to capture eleven different colours, producing the same effect as “one sees in a stained glass window.”

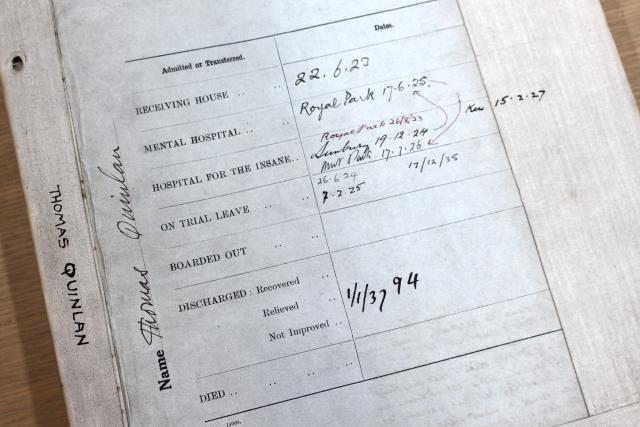

While his inventions seemed to be verging on the fanciful, it was his claim to have discovered the cure for cancer that saw him admitted to Royal Park Psychiatric Hospital on 22 June 1923. After showing a Doctor Mandeley his papers on the subject, the doctor referred him for psychiatric assessment, as the papers “showed evidence of a disordered mental state”. Rather than medical theory, they included a method for creating rubber out of sheepskin, rambling speech notes and “meaningless foreign words purporting to be scientific terms.”

Quinlan protested that “the idea of his being considered insane is perfectly ludicrous” and the admissions doctor noted that Quinlan “was quite plausible” but nevertheless he spent the next fourteen years of his life being admitted to various Melbourne mental health institutions, finally being discharged from Kew Asylum on new year’s day 1937.

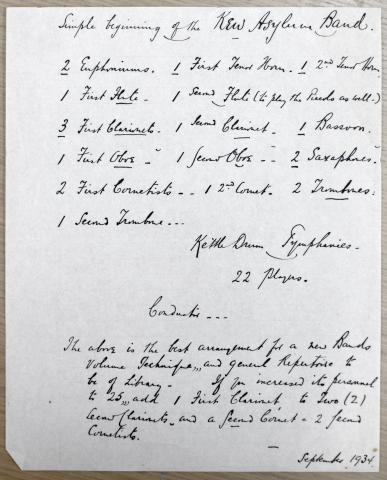

In hospital it seems that Quinlan found his passion for music had yet to be exhausted and amongst the pages of doctors’ observations in his file, there are also letters and plans from Quinlan, including records of his attempts to start the ‘Kew Asylum Band’.

Quinlan’s file is part of a unit titled “(1937) Ma - Wr; (1938) Ab - Lu; Ma - Zi; (1939) Ac – Ja, Patient Clinical Notes” PROV, VPRS 7693/P1, Unit 18. This box contains the patient histories of a number of asylum residents during the 1920s and 1930s and provides fascinating insights into both the individuals and the mental health system in Australia during this time.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples