Last updated:

‘“… From squalor and vice to virtue and knowledge …”: the rise of Melbourne’s Ragged School system’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Amber Graciana Evangelista.

This is a peer reviewed article.

The responses of Melbourne’s philanthropists to increasing levels of poverty and illiteracy among the urban poor in the late Nineteenth Century are well documented. However, studies of Melbourne’s early charity movements often view the movements through a local and secular lens, and the links between charity movements in Melbourne and Britain are yet to be thoroughly explored. Similarly, most histories of Melburnian charities give little attention to their religious roots, although as in Britain these were extensive. One important Melbourne charity, the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, has not received any significant attention and its international and religious roots have not yet been explored. My article examines the motivations and nature of this association, which provided free schooling to Melbourne’s destitute children, from as early as 1859. It does so in order to demonstrate how strongly British Evangelical charity movements influenced those in Melbourne. Specifically, through an in-depth study of the Hornbrook Ragged Schools I aim to demonstrate how British Evangelical charity movements directly influenced the establishment and management of Melbourne’s charity movements. Drawing attention to new sources including school registration files and annual reports, this article provides a short history of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, and case studies of Hornbrook Ragged Schools in the ‘Little Lon’ district, Collingwood and Prahran. In doing so it documents the influence the British Evangelical charity movement exerted over one of Melbourne’s most popular charities and aims to situate Melbourne’s own unique Ragged School movement in an international and ideological context.

In 1859, Hester Hornbrook, an elderly Evangelical philanthropist, established Melbourne’s first Ragged School on Cambridge Street, Collingwood. At first glance, Hester was an unlikely founder for what was perhaps Australia’s most focused and tightly organised Ragged School system. She was an aged woman ‘without riches, without position, without influence, without a party’, yet strong, determined devotion to her religion motivated her to establish Melbourne’s Ragged School system. Hornbrook was elderly; at the time of the establishment of her first school she was 74 years-of-age, and was considered to have ‘attained an age far beyond that ordinarily allotted to mankind’.[1] She was also not particularly wealthy. A woman of ‘slender means’,[2] Hornbrook’s total estate did not exceed £500.[3] Although this appears to make her an unlikely philanthropist, as a devout Anglican and disciple of Melbourne’s Evangelical movement, Hester’s zealous involvement in Melbourne’s voluntary charity movement was to be expected.

Very little else is known about Hornbrook. Although she founded Melbourne’s Ragged School movement and played a central role in the establishment of several significant charities, as well as in the development of Melbourne’s education system, Hester Hornbrook is noticeably absent in most histories of Melbourne, particularly accounts of Melburnian philanthropy and education. She is also absent from the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Roslyn Otzen, one of the very few to acknowledge her, notes ‘there is scarcely a trace of her left for the historian to find’.[4] Perhaps due to her modesty – though more likely, due to her gender – the only remaining references to Hornbrook are found in annual reports, pamphlets, and in the obituaries published after her death. Charity work was considered a worthy and acceptable activity for middle class and wealthy women to undertake. Understandings of gender at the time cast women as motherly and caring; as a result women were viewed as the ideal candidates to carry out ennobling welfare work.[5]

Before establishing the schools that bore her name, Hornbrook devoted her time to voluntary work as a member of Melbourne’s Evangelical movement. The movement placed particular emphasis on the importance of conversion and ‘evangelistic activism’, which was undertaken with fervour through charity work.[6] For Evangelicals, charity work was viewed as a means to fulfil one’s Christian duty of compassion and unconditional love for others, while simultaneously fulfilling the duty to guide others from sinfulness and condemnation towards a path of forgiveness and ascension.[7] Following the lead of London Evangelicals, Melbourne’s Evangelicals placed particular significance on the use of charity to improve the lives of the social underclass through spiritual revival.[8] It was believed that bringing individuals under ‘kindly Christian instruction’ could in turn bring about social and moral change.[9] For Hornbrook, this culminated in her establishment of eight Ragged Schools in Collingwood, Prahran and Melbourne’s CBD.

To British Evangelicals, Melbourne represented a modern-day Gomorrah in need of salvation[10] Poverty and destitution were, in the eyes of Nineteenth-Century Evangelical philanthropists, the consequence of personal moral deficiencies. Melbourne’s inhabitants were seen to be threatened by ‘the temptations, the depravity, the suffering, the crime, the vile associations of a great city’.[11] According to Davison and Dunstan’s study of early Melburnian outcasts, these attitudes stemmed from the moralistic assumption that one was responsible for one’s own fate. Swain supports this notion, observing that attitudes were ‘socially regressive’, and the poor were seen as being somehow ‘responsible for their own fate’.[12]

The poverty that affected many Melburnian families was then considered largely the consequence of poor decisions and moral depravity.[13] It was perceived as a potentially contagious plague of the body, soul and mind; a foul ‘condition’ synonymous with disease and ill health.[14] Contemporaneous writings explained that poverty was the condition of those ‘… living in unwholesome ways, hatching crimes, breeding vice, propagating disease and creating a foul atmosphere …’[15] From the view point of Evangelicals, if individuals were brought to God and transformed, many of the ‘symptoms’ of destitution and poverty could be treated.[16] It was believed that ‘ignorance, vice, and poverty go hand in hand’.[17] This attitude towards poverty, which O’Brien and Dickey portray as rooted in judgement and condescending in nature, fuelled the belief that education in the word of God could attend to the ‘temporal and eternal welfare’ of the lowest classes.[18] Dickey and O’Brien both conclude that these attitudes failed to address poverty’s structural causes.[19] Instead, reflective of a dogmatic confidence in their theology, Evangelicals believed that if they could simply return Melbourne’s lost sheep to the flock, so to speak, poverty and vice would be drastically reduced. As a devout Anglican and prominent member of the Melbourne Evangelical movement, it is not surprising then that Hester Hornbrook saw it as her Christian duty to provide relief to Melbourne’s destitute by bringing them under so-called ‘kindly Christian care’ and instruction.

The Hornbrook Ragged Schools

Hornbrook’s motivations for establishing her Ragged Schools provides valuable insight into what drove philanthropists in her time. Although very little is known about Hester Hornbrook, records attesting to her devotion to Evangelical theology are numerous. As a strict Evangelical, Hornbrook could be considered a typical mid-Nineteenth-Century Melburnian philanthropist. Since 1850 Melbourne’s charity movement had followed the lead of those in London, where Evangelicalism dominated.[20] Between 1850 and 1860 small numbers of local Evangelical colonists began to recruit ordained Evangelical clergy from Britain, through the assistance of Charles Perry, Bishop of Victoria. At the same time, newly-arrived British immigrants brought with them the evangelical traditions of home.[21] This dual pressure, exerted from below through local colonists, and from above from members of authority such as Perry, resulted in a strong Evangelical culture among Melbourne Anglicans. [22] As was the case in London, this centred around a heavy emphasis on charity.

As a devoted Evangelical, Hornbrook conducted regular relief work among Melbourne’s urban poor. According to newspaper accounts, by 1854 this work inspired in her a deep concern for what she perceived as increasing destitution and declining religious knowledge. In response, accompanied by other Evangelical philanthropists, including renowned Scottish Evangelical and temperance movement leader Dr John Singleton and his wife Isabella Singleton, Hornbrook drew further inspiration from a key British Evangelical institution – the London City Mission. Catherine Waterhouse, in a commissioned history of the Melbourne City Mission (MCM), notes that together, these Evangelical philanthropists agreed that a mission was ‘much required’.[23] In early July 1854, at a meeting of six hundred Melbourne philanthropists, Dr Perry and Henry Langlands described to the audience the ways in which Melbourne could take inspiration from the workings of the London City Mission and the British City Mission model.[24] At these meetings the Melbourne City Mission, based on the London City Mission model, was established, with Hornbrook heading the Ladies Melbourne and Suburban Mission.[25] In their discussion of the MCM, Singleton and Hornbrook regularly referenced the London City Mission model. It seems that even across vast distances and without any direct means of communication, London’s Evangelical movement had continued to exert a direct influence on the charitable endeavours of Australia’s philanthropists.

At this time, philanthropic endeavours drew almost entirely from English models; indeed it was from another British charity that Hester Hornbrook drew inspiration for a solution to the proliferation of poor children without religious education. Since 1845, concerned London missionaries, middle-class welldoers and members of the charitable aristocracy, had tackled the same issue through the introduction of a network of free ‘Ragged Schools’, a term coined by RS Starey, who became the Ragged School Union treasurer, because it ‘forcibly and tritely expressed the low character and condition of the pupils, so thoroughly depraved in mind and ragged in apparel’.[26] Members of the London City Mission had established several day schools for ‘the lowest poor’ to provide ‘… gratuitous instruction to children of the poor who have no other way of learning to read the word of God …’[27] The establishment of these schools demonstrate Dickey and O’Brien’s conclusions that Evangelical charities’ ‘essential aim was religious’, and therefore failed to greatly challenge social or structural causes of poverty.[28] Although the London Ragged Schools aimed to provide a place of education for those children who ‘from their poverty or ragged condition, are prevented attending any other place of religious instruction’, their primary purpose was to convert and elevate those poor who lacked religious education.[29] Driven by their fervent belief in the importance of this work, over the course of thirteen years 352 schools – including Sunday schools, day schools and evening schools – were established, and provided basic and scriptural education to over 21,500 scholars.[30] The cause was enthusiastically sponsored by numerous influential public figures including the Seventh Earl of Shaftsbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Charles Dickens.[31] It is perhaps not surprising then that such a well-known and well-loved Evangelical movement influenced Evangelical philanthropists in Australian colonies.

Victoria was not the only place in Australia to follow the example of Britain’s Ragged School Union (RSU), nor was it the first. Hobart Town in Van Dieman’s Land was in fact the first place to adopt a Ragged School network of its own, just under a decade after Britain’s RSU was established. Founded in 1854, the Hobart Town Ragged School Association provided free schooling for over 4000 children by the end of the 1860s.[32] Melbourne was the next Australian city to adopt the Ragged Schools model in 1859, followed closely by Sydney, where in 1862 a Ragged School system was established in The Rocks.[33] Although the Australian movements all indirectly grew from the British RSU within less than a decade, none of the Australian movements were alike. The movements of Hobart, Sydney and Melbourne were entirely independent. Each were organised by separate organisations and did not communicate or collectively organise. Each of these three Australian Ragged Schools movements, then, has its own unique story that deserves its own telling.

To return to Melbourne, the history of the Victorian Ragged School Network begins with Hester Hornbrook’s work with the Melbourne City Mission. The origins of Victoria’s Ragged Schools can tell us much about what motivated philanthropists, and in what values their actions were rooted. The Hornbrook Ragged Schools were profoundly religious in their motivation, and their direction was driven by British Evangelicalism. Demonstrating how the schools arose from Evangelicalism allows for a broader view of Melbourne’s Ragged School system, and places the system in an international and religious context. The manner in which Hornbrook established the first school is testament to this. Deeply involved in the workings of the new Melbourne City Mission, it was from one of the MCM missionaries, newly-arrived Joseph Greathead, that Hornbrook drew inspiration to introduce the Ragged School system to Melbourne.[34] As an Evangelical missionary, Greathead meticulously recorded his daily work visiting local homes, and quickly began to lament to his peers about the lack of religious knowledge among the city’s younger generations.[35] He perceived tragedy in the laneways and streets of Collingwood, children ran about poorly fed and poorly clothed, uneducated in the word of God and with little prospect of a decent life ahead of them. However, to Greathead, worse still was the fact that the children of Collingwood lacked any means to better their spiritual situation: ‘They cannot read, have no idea of the way of Salvation’.[36] In true Evangelical manner, Greathead was more struck by the children’s godlessness than by their material poverty.

Greathead’s emphasis on the children’s lack of religious schooling over their physical wellbeing is demonstrative of an attitude commonly adopted by Melburnian philanthropists. Typically, philanthropists positioned moral deficiencies over physical hardship or material deprivations as issues of concern. Although these attitudes have been extensively investigated in relation to other charities by historians such as Swain, Otzen and O’Brien, there has not yet been any exploration of the role they played in the establishment of what was potentially Australia’s largest and most organised Ragged School network, a system that played an important role in the development of Victoria’s education system. For Greathead, his Evangelical perception of poverty led him to seek help in providing impoverished children with what he viewed as a solution to their condition – an education in scripture. As president of the mission that employed him, Hornbrook was regularly exposed to Greathead’s concern for the children of Collingwood and took it upon herself to find a remedy.[37] It is important to note here that rather than assist these children through the provision of practical skills and education, in accordance with Evangelical tradition and the beliefs of the MCM, both Greathead and Hornbrook viewed religious education as the best, and only, complete solution to poverty.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the term ‘Ragged School’ was first adopted by Hornbrook and her assisting philanthropists. However, as a prominent Melbourne City Mission member and founder who demonstrated close knowledge of the London City Mission model, it is very likely that Hornbrook was aware of the name of the school system that was so closely linked to the London City Mission.[38] Thomas A’Beckett, a patron of the schools and registrar of the Melbourne Anglican Diocese, remarked several years later at a general meeting that the term ‘Ragged’ was simply ‘one of those good things … borrowed from England’.[39] This adoption of the British name provides another important clue as to the close links between the Melbourne and British movements, while the presence of influential Anglican Church members in the movement points to the movement’s clear Evangelical links. At the time of the establishment of the Hornbrook schools, which occurred under the direction of Bishop Perry, the Melbourne Anglican church was distinctly Evangelical.[40]

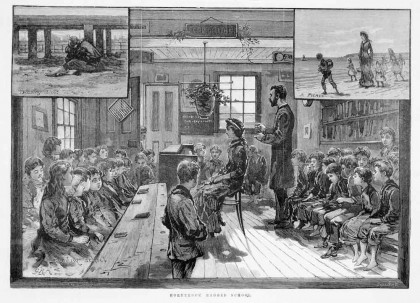

However, although profoundly religious in their motivations, the schools did provide an important service. Prior to the introduction of Ragged Schools poor children had few means to secure an education. Students were required to pay a weekly fee for their schooling, an expense that many families could simply not afford. Those who could afford a small fee were often shunned from local schools due to their shabby appearance, lack of suitable clothes and shoes, lice and illness. It is important to bear in mind though, that although such children were the beneficiaries of the Hornbrook schools, relieving their material poverty was not the main concern of the Hornbrook system. Hornbrook, reflective of contemporary Evangelical attitudes, was more concerned with destitute children’s lack of religious schooling. In the minds of Hornbrook and her contemporary philanthropists, poverty bred poverty. Immorality would spread, if religious teachings were not imparted upon the poor. Ragged Schools, then, must be viewed within the context of religious trends and attitudes to poverty. Previous studies of Australia’s, and in particular Melbourne’s, Ragged Schools tend to praise the inclusive nature of the schools and little attention has yet been drawn to their motivations. Far from being simple schools aimed to offer poor children a basic education and a future, the schools were far more concerned with the children’s spiritual wellbeing.

Prior to the establishment of the Hornbrook system, children were sometimes able to attend Sunday school classes run by missionaries but otherwise lacked any thorough education. More concerning to Hornbrook, they completely lacked religious teachings. In response, annual reports of the organisation show that in November 1859, Hester Hornbrook, utilising her connections and fundraising abilities, opened the first Melbourne Ragged School on Smith St, Collingwood.[41] The school aimed to ‘reclaim’ those ‘… children of the very lowest class among the population – those who, from extreme poverty – the result, too often, although not always, of intemperance and vice – were unable to take advantage of the ordinary existing schools’.[42] The aim then, was to provide otherwise uneducated and godless children with a religious education, in order to prevent their further descent into poverty and depravity. Rather than provide practical skills to children who faced future unemployment and a life of poverty, the schools aimed to assist the moral and social ascendance of these children, and the protection of their souls.

Schooling the ‘Little pariahs’ of Collingwood, Prahran and and ‘Little Lon’

As the first of the Hornbrook Ragged Schools, the one in Collingwood provided a proving ground for Hornbrook to refine the process of establishing and managing such a school. It was vital to Hornbrook’s Evangelicalism that the system be geographically spread so that the number of children ‘converted’ within Ragged Schools could be maximised. Central to this branch of Evangelicalism was the belief in the importance of conversion. For Hornbrook and her followers, reaching the greatest possible number of potential converts was of upmost importance. As a result, the Collingwood school was an important test case which once proven provided a model that Hornbrook quickly repeated.

An analysis of how the first schools were established provides insight into the functioning of the organisation, their priorities, and their ideology. First, Hornbrook recruited local children to the Collingwood school through the assistance of Collingwood missionaries and then gained funding for the teachers’ salary, books, slate and building rent by appealing for donations among the ladies of the Melbourne City Mission. The first organised financial reports of the school, dating from 1863, note that the Smith Street school cost roughly 90 pounds per year to run. Roughly 40 donors and subscribers covered these costs. The school, taught by Mrs Boyd, later relocated to Cambridge Street, and was attended by 30 to 40 students.[43] Newspaper records indicate that Hornbook was ‘speedily relieved’ of the care of the Smith Street school by ‘a few friends who undertook its management immediately’, thus allowing Hornbrook to scout for a location for her next school.[44] Hornbrook then gathered about her a dependable committee of donors and missionaries that began meeting regularly, and was thereby able to establish eight schools before her death in 1862, several of which she played a direct role in managing.[45] As in London, missionaries played a particularly strong role in the establishment of the schools, and were recruited by Hornbrook ‘to enquire into every new case of admission …’[46] This relationship was formalised in the creation of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association (HRSA) rules which provided guidance for the committee. Rule seven noted that all ‘inquiries shall be made into every new case of admission by a Member of Committee or a City Missionary …’[47] Both the annual reports and the rulebook demonstrate the centrality of Evangelism to the organisation, and the close ties between Hornbrook’s Ragged Schools and the MCM. The relationship between the two organisations was strong; the central committee of the HRSA often noted that ‘the city missionaries in the various districts proved valuable assistants, seeking out and sending to the schools many poor neglected children’.[48] With the help of the MCM, Hornbrook was quickly able to fill new school rooms with more pupils.

Hornbrook focused specifically on areas of the city identified by missionaries and other Evangelical philanthropists as hotbeds of sin and depravity – areas where gambling houses, brothels and hotels were plentiful and where inhabitants suffered severe impoverishment.[49] The locations of her schools were both practically and ideologically motivated. They corresponded directly with areas where the MCM conducted its work. Schools were established in Collingwood, Prahran and the blocks surrounding Little Bourke Street and Little Lonsdale Street – areas seen as dens of sin and vice, the product of Melburnian mammon.[50] By locating her schools within missionary districts, Hornbrook could utilise home visits conducted by missionaries as a means to recruit children for the schools. According to the HRSA’s central committee, Hornbrook’s schools were as ‘intimately concerned with the welfare of the state’ as they were with its citizens. Governor of Victoria Sir Henry Barkley noted in his speech at the first annual meeting of the Hornbrook Society that it was through ‘training the young in the paths of rectitude’ that the moral condition of the ‘lower classes’ could hopefully be raised, as ‘it would be a thousand pities that such a class should be allowed to establish themselves here’.[51]

Under the watch of the HRSA, by late 1863 nine Hornbrook Ragged Schools were in operation. Five were located in Collingwood, the area to which Hornbrook was originally drawn. Two more functioned in Prahran, in working-class zones that were the focus of significant attention from missionaries due to the vast numbers of poor factory workers and labourers who resided in over-crowded pockets of the otherwise affluent area.[52] A further two were opened in east and west Little Bourke Street, an area well known for its slums and high crime rates. Another was established near Little Lonsdale Street, an area of the city Hornbrook, like many other philanthropists, had turned her eye to before her death. Hornbrook identified the area as a particular threat to Melbourne’s morality. The home of gambling dens, brothels, hotels and immigrant housing, the neighbourhood was seen by Evangelicals as overflowing with vice and sin. Gamblers, bachelors, prostitutes and immigrants provided the Evangelicals with what they perceived as a depraved populous in need of salvation. Seen as an area in which much ‘improvement’ could be made, ‘Little Lon’ was the subject of enormous attention from Evangelicals, including Hester Hornbrook.

Following the official creation of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, the Hornbrook schools were run according to central rules and structures strictly regulated by the association. As a result, the first accurate roll counts from the schools were collected. These tell us that by 1863 over 300 students were enrolled in the Hornbrook Ragged Schools and were subject to the organisation’s ‘efforts to reclaim and instruct the little Arabs of the streets and lanes’. An analysis of the actual numbers of enrolments provides a new insight into the success of the organisation. So far, total enrolment numbers have not been analysed or compiled. Between 1860 and 1863, enrolment numbers on the Smith Street school rolls doubled. By 1865 the total number of children attending Hornbrook Ragged Schools surpassed 800.[53] By 1870, the schools were teaching over 1000 children.[54] As a point of comparison, local state schools sharing the same district as the inner-city Hornbrook Ragged Schools were capable of providing for 1500 children.[55] The exact number of students taught at the Ragged Schools is difficult to determine, however, a rough estimation based on class enrolments gathered from records held by Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) and the HRSA’s annual reports, puts the total number of children taught by the Ragged Schools between 1859 and 1872 at close to 2100.[56] This figure is calculated cautiously and errs on the conservative side. As noted at the organisation’s first annual meeting, the number of enrolments did not necessarily match the number of children attending the schools. In 1863, 558 children were enrolled with the HRSA, however the organisation noted the attendance of around 900 students.[57] In light of this, the number of children who received schooling at the Hornbrook Ragged Schools could in fact be double this initial estimate. Despite these reservations and concerns, it is clear that the total number of children taught at Hornbrook Ragged Schools is significant. In the decade between 1860 and 1870, the number of destitute children in Melbourne averaged around 10,000.[58] Of these, 15% received an education provided by the Victorian Government.[59] The estimate demonstrates that during its most successful years, the Hornbrook schools provided education for at least a further 10% of the Victorian population of destitute children. This increases the estimated percentage of destitute children in schools to at least 25%.[60] Apart from demonstrating the rapid expansion of the Hornbrook schools, this informs us of the nature of the organisation and the ideology that drove it. For Evangelicals, increasing the number of conversions to the faith was of primary importance, to save as many souls from the spiritual corruption that manifested itself as poverty.

Additionally, these important numbers demonstrate that at this time the state education system for destitute children was inadequate. In areas such as Collingwood, Little Lon and Prahran, the number of uneducated children was far higher than other localities. It was in these areas that the HRSA focused with great fervour. That the HRSA were able to reach such high levels of enrolment can tell us two things. Firstly, that need for free schools was real; wherever a school was opened there was no shortage of attending students. Secondly, it could also simply demonstrate the intense dedication Evangelicals had to their work. Perhaps rather than being the result of extreme need, high enrolment levels may be indicative of the fact that missionaries and HRSA volunteers were intensely devoted and effective recruiters. We do know that because of their devotion to their creed – which emphasises conversion and recruitment – HRSA and MCM volunteers did not work simply because they were driven by compassion, but because such work was considered their Christian duty.

Prahran and Cumberland Place

The brief previous studies of Melbourne Ragged Schools that were conducted in the 1980s did not analyse the Prahran school, nor did they make use of the wealth of information stored in the records of closed government schools held by PROV. These records, which have previously received scant historical attention, allow an in-depth case study of a Ragged School, and provide an insight beyond that of the HRSA records. Extensive records about the Prahran Ragged School can be found among these files. One of the earlier and more successful schools, the Prahran Ragged School is a good example of how Evangelical ideology governed the running of the school. It first opened its doors in 1862, in a pocket of the suburb identified by MCM missionaries as an area of concern, and maintained strong links to the MCM. Ties to the MCM were vital to the maintenance of the HRSA’s Evangelical vision; the schools relied heavily on local missionaries, not only to source new students, but to assist with the imparting of Evangelical ideology upon their enrolled students. This is particularly noticeable in the case of the Prahran Ragged School. Within a year of its opening, a local mission was established nearby, and its missionary Mr Smith took an active role recruiting local children to the school.[61] By the end of the year, the Hornbrook Ragged School Association reported that at this school ‘13 of the children can read the Bible; 20 are in the Second Sequel; 8 are writing in copy books; 20 on slates; 14 can sew pretty well; 4 are learning to darn’.[62] The children were ‘greatly attached to their teacher’.[63] School registration documents held by PROV reveal that the school’s teacher, Ms Brown, remained in the school for over 40 years.[64] Ms Brown supplemented the school’s Evangelical teachings in a manner that was not typical of the other Hornbrook schools. Alongside strict scriptural teachings, she worked to establish a library for the students and their parents and often sourced toys such as balls, bats and on one occasion a rocking horse.[65]

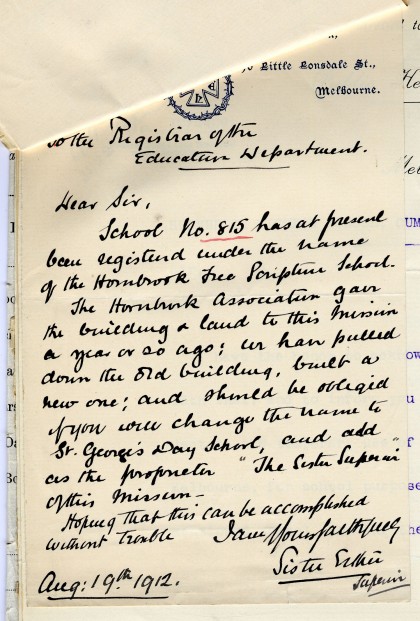

According to documents held at PROV the school moved location several times in its early years, and is listed at various times in Earl Street, Duke Street and Eastbourne Street, all of which are in the same block between Hornby and Chapel streets. One of its last relocations placed it in a cold and draughty 24 by 36 ft brick hall at 45 Eastbourne Street. Unlike the other Hornbrook schools, until its closure in 1910 it bore the name ‘Hornbrook Scripture Reading School’ in reflection of its religious objectives, and continued to teach scripture classes.[66] It abided strictly by the Ragged School’s primary objective: ‘the gearing in, and instructing in the Word of God’.[67] The PROV records indicate that the school retained its religious teachings until its closure in 1910, demonstrating the endurance of the HRSA’s Evangelical motivation. Although the Prahran school’s purported aim was to provide education to children, its primary goal was religious. School registration documents indicate that it operated until 1910 for an average of 40 pupils per day, making it one of the longest enduring Hornbrook Ragged Schools. Significantly, it is the only one of the Hornbrook Ragged Schools that has a direct link to the present; in reference to local history a childcare centre located on one of the original sites on Earl Street continues to bear the name ‘Hornbrook’.

PROV also holds records relating to another of the early schools, situated near Lonsdale Street, which provides another excellent insight into how Evangelical attitudes towards charity and poverty were put to use in the establishment of the Hornbrook schools. School registration documents show that Hornbrook Scripture School no. 815 was established soon after Hester Hornbrook’s death in late 1862, and quickly gained particular praise and attention due to its ‘good work’ in one of Melbourne’s most notorious slums. Located at 37 Cumberland Place in a small timber building, behind Little Lonsdale Street and near McCormack Place in the infamous Little Lon district, the school was a favourite example of how the ‘good influence’ of religion and charity could be exercised in what was perceived as a lowly area. The Hornbrook Ragged School Association regularly reported the ‘good influence the school has been found to exercise in the neighbourhood’. To the HRSA, if the work of the school was spilling into the local neighbourhood, their goal to elevate the lower classes was being achieved. However, HRSA documents fail to note that there were a total of five state schools functioning in the same area, many of which offered programs for destitute children. After 1872, all of these schools were officially opened to destitute children and provided free education to members of all classes. Regardless of this, the HRSA city school continued to operate, citing a lack of religious teachings in local state schools as the reason for their continuance.

The HRSA’s Evangelical concern over the moral standing of the citizens of the city ‘slums’ made the city schools popular among proponents of the organisation. Located near Chinatown, the area was home to children from a wide variety of backgrounds, including Chinese, Italian and ‘Syrian’ – a term once used to describe any Arabic-speaking person or community. The Hornbrook Ragged School Association saw the locality as a dangerous one, full of gambling dens, brothels and hotels. Establishing a school there was seen as an excellent opportunity to elevate the moral and religious character of some of inner Melbourne’s lowest inhabitants. These attitudes demonstrate the fundamental ideology behind the HRSA; that poverty is the result of moral depravity, and if morally elevated through schooling in scripture, symptoms of poverty could be drastically reduced. Poverty was perceived by the HRSA as a dirty, immoral condition, and education was viewed as a tool for salvation. Religious education was a means to elevate the lower classes; the HRSA’s charity was not primarily the result of kind-hearted compassion, but of a dogmatic Evangelical belief system.

Located in the midst of the city’s ‘slum’ district, the HRSA were particularly enthusiastic about the Cumberland Place school. A large portion of the organisation’s funds and attention were directed at this school, which was located near a brothel and a local pub. Due to the HRSA’s concern for the locality, the school was one of the longest lasting and remained operational until 1907.[68] The school continued to function even after the advent of theEducation Act 1872, which introduced free, compulsory education for all children in Victoria. This was due to the HRSA’s strong belief in the locality’s need for a pillar of moral strength to ensure at least some local children received religious schooling. However, conditions at the school were poor. The 1877 Royal Commission of Enquiry into the State of Public Education in Victoria described the school as situated ‘in an alley, and the children are often taught in the road for want of room inside.’[69] Worse still, ‘[n]ot long ago two Chinese brothels were opened hard by, and the children could watch the customers going in and out during the class-work’.[70] It is not surprising then, that in the years following the wide-spread introduction of local state schools, enrolments at the HRSA school dwindled as parents began to favour state-run schools over the religious teachings of the Hornbrook school. As a result of poor enrolments, at the turn of the century the school had passed into the hands of the sisters of the Church of England Mission to Streets and Lanes, and reportedly had only nine scholars in attendance.[71] Although its official name became the ‘St George Mission Hall’ the school continued to be commonly known as ‘the Hornbrook School’.[72] PROV school records show that in February 1912 an inspection by the Public Health Department deemed the original building ‘quite unsuited for day school purposes’ due to ‘unsatisfactory lighting, the total want of ventilation and other defects.’[73] As a result the building was demolished and a brick school was built in its place. This had further impact upon the school’s popularity. The HRSA gave up management of the school and it was re-registered under the name ‘St George’s Day School’ upon re-opening in August 1912. The school continued to operate with approximately twenty students until its final closure in 1925.

‘A Ragged School without the name’

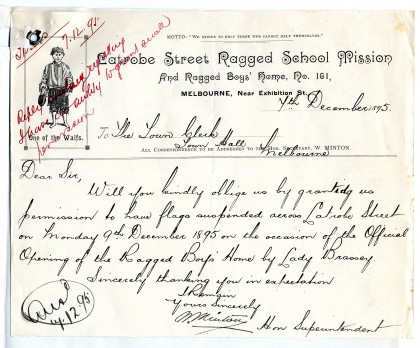

As well as establishing a network of free schools, the Hornbrook Ragged School system exerted significant influence on the workings of other charities. Several organisations adopted the model and ideology imported by Hornbrook, and established their own ‘Ragged Schools’, although they did not enjoy the success and repute of the Hornbrook schools, mainly because they failed to gather donations and subscriptions, as the main benefactors were already supporting the Hornbrook schools. However, the model was replicated several times in the late Nineteenth Century. Fashioned in a similar manner as the Hornbrook schools, the ‘Latrobe St Ragged School Mission’ and ‘Ragged Boy’s Home’ opened in 1895.[74] After changing hands to the St Johns Church on Lonsdale Street, and again in 1907, this time to the Sisters of the Church of England Mission to Streets and Lanes, the school operated for another 15 years under the sort of model popularised by the Hornbrook Ragged School Association. Students came from ‘hard-working’ poor families, and were taught commercial skills and assisted in finding employment upon completion of their studies.[75] As Victorian state education became more accessible, the need for schools such as these diminished. Those who did attend these schools were often orphans, or the children of parents who failed to send their children to local state schools. However, by 1922 the benefactors of St Johns were struggling with the upkeep of the school and it was referred to the Public Health Department for demolition due to its ‘unsatisfactory … general sanitary state’.[76] Due to the presence of more efficient state schools nearby, rather than rebuilding, St Johns was struck from the registers and the thirty children attending were dismissed.[77]

The success enjoyed by Hornbrook Ragged School Association also influenced several other church groups and charities beside the Lonsdale Street Ragged School Mission to adapt the model. The earliest non-Hornbrook Ragged School was established on Little Bourke Street – quite close to a Hornbrook school – in 1860.[78] The ‘Gospel Mission Hall’ School, taught by James Ellis worked on the same model as the first of the Hornbrook schools, and was established one year after the first Hornbrook Ragged School. A ‘Ragged School without the name’, children at Gospel Hall received daily free meals and school hours were flexible, in order to provide for students who were required to work or beg.[79] Soon after its establishment the school was taken over by the Department of Education and became known as the local government-run Ragged School. That the Department of Education saw the merit of a free school system for destitute children goes some way to demonstrate that at some point there was a need for the Hornbrook schools, and that the provision of free schooling was considered a noble and necessary cause. However a published critique of the school noted that although celebrated with ‘a great flourish of trumpets’ and self congratulation, the model it was based upon was ‘clumsy and very expensive’.[80]

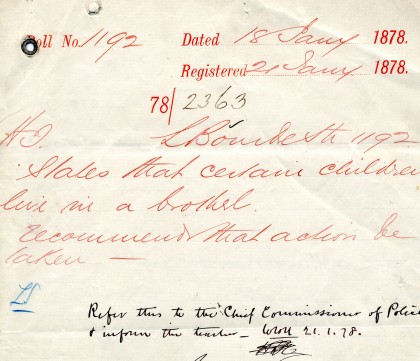

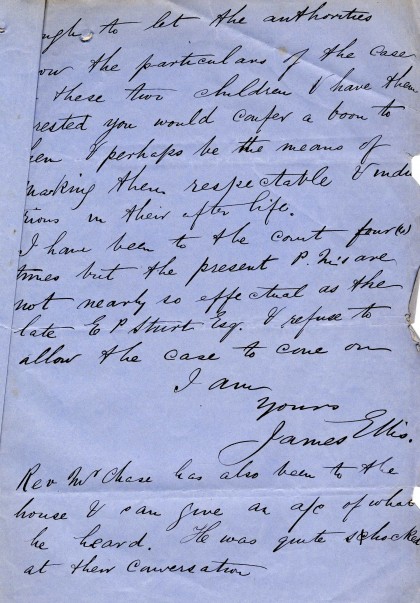

The case of the Gospel Hall School has not yet been included in studies of Ragged Schools, however it does demonstrate how the ideas behind the HRSA permeated popular society and even into the state government. The HRSA model was considered effective and necessary enough to be replicated by the Victorian Department of Education. School records held by PROV provide fascinating details into the day-to-day running of the school, which functioned in a similar manner to the Hornbrook schools, yet without its central organisation and large support network. Regardless of this, the school was well attended, and by 1872 the school’s daily attendance averaged 130 students. Although Gospel Hall did not provide religious teaching like Hornbrook, Ellis was motivated by a desire to elevate the children of the destitute.[81] He viewed his work as able to ‘mark [sic] them respectable and make them victorious in the afterlife’.[82] Like members of the HRSA, he was rather judgmental of the character of his students and their families. In 1878 James Ellis wrote to the Department of Education to report that several of his students were residing in a house that was ‘a resort for low women’.[83] Upon reporting the matter to the police, Ellis was dismayed that the officers ‘did not go to the house for the purpose of assessing the children, but any women that they should happen to know’.[84] Ellis, in letters to the Department of Education also described students’ parents as ‘generally drunk’, ‘well known loafers’ and ‘well known prostitutes’, and registered his concern that several of his students resided in a stable only ‘12ft by 10ft’ and were in the habit of ‘running about naked’.[85] Ellis stood firm in the belief that the students and their parents were lesser individuals, occasionally writing to the Department of Education to urge legal action upon families and for the removal of children who he deemed ‘not fit subjects for the school’.[86] Ellis’s descriptions of his students mirror the attitudes towards the poor adopted by many of early Melbourne’s philanthropists. Poverty was the result of depravity and vice, consequently those who did not seek to better themselves were to be looked down upon.

A slow decline

After two decades of successful operations, changes in Victoria’s education and welfare systems in the late Nineteenth Century reduced Melbourne’s need for a Ragged School system. In 1872 Victoria’s Education Act introduced a new system of free, compulsory and secular education for all children. Theoretically, this meant that destitute children were no longer barred from state schools and now had equal access to state education. As a result, members of the public who had so passionately supported the Hornbrook Ragged Schools soon began to withdraw their support. After the introduction of the Education Act, destitute families were now – at least in theory – able to send their children to local state schools. All state schools now provided free education and were open to children of all classes and backgrounds. As a result many practically-minded supporters of the HRSA no longer saw the need for the Hornbrook schools and withdrew their financial support. Within a year of the introduction of the 1872 Act, subscription numbers and donations had noticeably declined from over 1000 pounds to just under 300.[87] The HRSA also began to see a slow decline in enrolments. Families who had enrolled their children at Hornbrook schools were now able to send their children to larger state schools. This proved a challenge for the Hornbrook schools. In an analysis of the Hornbrook schools, John Stanley James, better known by his pen name ‘Vagabond’, astutely noted that when a state schoolhouse was built, ‘the higher education given there caused parents to remove their children from institutions where the boys, at least, learnt little else but texts’.[88] However, members of the HRSA were alarmed by the increase of secular schooling. In their eyes, education in literacy and numeracy only addressed half the problem. To them, religious education was the element that would save the poor. Secular in nature, state school education was therefore considered inadequate. At a general meeting to address the issue, HRSA member Reverend Vanoe declared that ‘to accept a national system without religion would be to welcome a moral death’.[89] James astutely noted that ‘the Hornbrook Association is worked on the idea that, without a certain amount of Scripture teaching, education is of no avail’.[90] To the HRSA, the need for Ragged Schools was just as great, without them the moral deterioration of the lower classes would continue. Unfortunately for the HRSA, public sentiment did not agree, and public support for the organisation quickly dwindled.

The economic depression experienced in Melbourne in the early 1890s briefly delayed the decline of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, but for the most part, the Melbourne Ragged School system did not endure into the Twentieth Century. The depression of the early 1890s resulted in increased urban poverty. In this climate, faced with terrible deprivation and suffering, the Hornbrook schools adjusted their model and began to provide basic welfare, including the provision of daily meals. The schools also worked with the MCM to link student families with other charities, and provided students with clothing and boots. As a result, local families withdrew their children from state schools, which offered no comparable services. In times of desperate need, families were willing to sacrifice the quality of their children’s education for a good meal. As a result, the Hornbrook schools enjoyed a brief return to popularity, matched by increased funding from those in a position to donate. However, when Melbourne’s economy began to recover, parents once again withdrew their children from Hornbrook schools and re-enrolled them in state schools, which provided more thorough education.

Over the first decade of the Twentieth Century, the Hornbrook Ragged School Association dwindled in size as the majority of the schools closed. The organisation struggled to retain enrolments and funding, and eventually broke one of their central rules and began to charge fees. By 1906 only three schools remained. The organisation’s most successful schools – Prahran and Cumberland Place – remained operational until 1910. By that time, the other schools had either closed, or been handed over to local churches or the Church of England Diocese Mission of Streets and Lanes. The name of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association endured until 1912, when the group handed over ownership of their properties to the Mission of Streets and Lanes, the Free Kindergarten Union, and Melbourne City Mission. After that, only the Prahran school endured in any lasting form – the name ‘Hornbrook’ has remained attached to the Prahran school, which converted to a free kindergarten in 1910.

The achievements of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association could be viewed as being motivated by sincere concern for the poor. However the role of religious motivation needs to be further explored. The Hornbrook Ragged Association perceived a link between poverty, sin and a lack of religious knowledge. Hornbrook schools did not seek to simply provide children with a free education in order to better their job prospects and living conditions; their primary objective was to acquaint children and families with God. Hornbrook Ragged Schools were viewed as institutions through which young souls could be saved through ‘enobling’ education.[91] It was intended that children be ‘… dragged from squalor and vice into contact with the influences of virtue’, not only to improve their future prospects, but in order to elevate their moral character.[92] The HRSA saw poverty as a disease of the soul, and worked steadily to cure children of its symptoms and to guide them from temptation. This work was conducted zealously by members of the association, who were driven by the belief that ‘training the young in the paths of rectitude’ was part of their Christian ‘duty’.[93] The first regulation listed in the Hornbrook Ragged School Association list of rules insists that in all schools the ‘primary object of these schools shall be, the gearing in, and instructing in the Word of God’. It is also important to note that although thus motivated, the Hornbrook Ragged School Association were often very sincere in their compassion. The children of the schools received regular provisions. Aside from bibles and scripture training, on several occasions the children received clothing, boots, blankets and weekly bread.[94] Several of the HRSA teachers also sought to re-introduce play into the lives of children who often adopted adult roles in their households. The association threw annual parties and picnics, Christmas concerts and other play-dates, which were reportedly the source of great pleasure.[95] It is important to note, however, that accounts of these kindnesses were only given by the HRSA itself – there exists no record of these acts of welfare from the perspective of students or families.

While religious education was first and foremost, the Hornbrook Ragged Schools played an important role in improving the lives of their students, and their families. More significantly, the Hornbrook schools exerted considerable influence in Melbourne’s charity and education movements. However, it is important to bear in mind that the schools were the result of Evangelical beliefs. The members of the HRSA were not motivated primarily by kindness or compassion as we understand these concepts today, but by an unwavering belief in their Christian duty to provide religious education in order to relieve the symptoms of poverty and address an underlying spiritual corruption. Although ragged schools have been explored in the past, studies have failed to examine this element of the movement. This case study of the Hornbrook schools therefore seeks to introduce the schools in a new context. It is the first extensive exploration of the schools, and the first to extensively analyse the links between the organisation and Evangelicalism. It is not intended as the final word on the Hornbrook movement, but as a first, provisional exploration into the significance of Melbourne’s Ragged School system. I have drawn attention to the important role the schools played in the maintenance of contemporaneous attitudes towards poverty and changing ideas about education and philanthropy. The HRSA can serve as a useful thermometer with which to gauge the social climate surrounding poverty and education in Melbourne throughout the mid-to-late Nineteenth Century. Further research into the individual schools, the organisation, their founder, and the role of Evangelicalism is needed in order to properly situate the Melbourne Ragged School system within Melbourne’s unique history.

Endnotes

[1] ‘News of the Day’, Age, 7 January 1863, p. 4.

[2] ‘Hornbrook Ragged Schools of Melbourne: To the Editor of the Argus’, Argus, 24 March 1863, p. 4.

[3] Will of Hester Hornbrook, 1863, PROV, VPRS 7591/P1 Wills, Unit 15. By 1880, a shop-keeper could expect to earn roughly £400 pounds a year, while doctors, professionals and merchants earned from £600 to £2000 annually. This placed Mrs Hornbrook in the respectable middle class. Graeme Davison, The Rise and Fall of Marvellous Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1978, p. 191.

[4] Roslyn Otzen, ‘Charity and evangelisation: the Melbourne City Mission 1854–1914’, PhD Thesis, University of Melbourne, 1986, pp. 22–25, available at <http://hdl.handle.net/11343/35580>, accessed 10 October 2015.

[5] See Shurlee Swain, ‘Negotiating Poverty: women and charity in nineteenth-century Melbourne’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2007.

[6] Darrel Paproth, ‘Evangelical Movement’, entry on eMelbourne: the city past & present, University of Melbourne, 2008, available at <http://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00538b.htm>, accessed 9 September 2015.

[7] Graham Bowpitt, ‘Evangelical Christianity, Secular Humanism, and the Genesis of British Social Work’, British Journal of Social Work, Vol. 28, No. 5, 1998, pp. 679–670; Anne O’Brien, Poverty’s Prison: Poverty in New South Wales, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, p. 194; Brian Fletcher, ‘The Anglican Ascendancy 1788–1835’, in Bruce Kaye (ed.), Anglicanism in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002, p. 7; Shurlee Swain, ‘Do You Want Religion with That? Welfare History in a Secular Age’, History Australia, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2005, p. 79.4;

[8] Ibid.

[9] Anne O’Brien, ‘Charity and Philanthropy’, Sydney Journal, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2008, pp. 18–20.

[10] Brian Dickey, ‘Secular Advance and Diocesan Response 1861–1900’, in Bruce Kaye (ed.) Anglicanism in Australia, p. 52.

[11] ‘State of the day’, Argus, 14 September 1864, p. 4.

[12] Swain, ‘Do You Want Religion With That?’, p. 79.4; Swain, ‘Negotiating Poverty’, pp. 101–105.

[13] Attitudes such as this were closely tied with ideas about race and eugenics. Poverty and depravity was therefore also seen to be a condition afflicting those deemed to be racially inferior. As a result, Indigenous and Chinese populations attracted the intense interest of Evangelicals. Missionaries sought to ‘save’ their souls and re-educate them through often-extreme measures, the consequences of which Australian society is still coming to terms with. Stuart Piggin notes that the dedication of missionaries was ‘not always matched by their wisdom… Massacres continued… [and] missions and government co-operated in “smoothing the dying pillow”’ of Indigenous people, while Chinese were treated as heathens, contributing to ‘another sad chapter of Australian racism’. See Stuart Piggin, Spirit, Word and World: Evangelical Christianity in Australia, third edition, Acorn Press, Brunswick, Victoria, 2012.

[14] Graeme Davison, ‘Introduction’, in Graeme Davison, David Dunstand and Chris McConville (eds), The Outcasts of Melbourne: Essays in Social History, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1985, pp. 3–4.

[15] ‘Our City Poor’, Southern Cross, 16 October 1891, p. 5.

[16] O’Brien, ‘Charity and Philanthropy’, pp. 18–20.

[17] ‘News of the Day’, Age, 7 January 1863, p. 4.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Anne O’Brien, Philanthropy and Settler Colonialism, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2015, p. 3; Dickey, ‘Secular Advance and Diocesan Response 1861–1900’, p. 52; Swain, ‘Negotiating Poverty’, p. 101.

[20] Stuart Piggin, ‘Australian Anglicanism in a World Wide Context’, in Bruce Kaye (ed), Anglicanism in Australia, pp. 203–207.

[21] Piggin, Spirit, Word and World, pp. 14–16.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Catherine Waterhouse, Going Forward in Faith: a History of Melbourne City Mission, Melbourne City Mission, North Fitzroy, 1999, p. 25.

[24] Otzen, ‘Charity’, p. 22.

[25] ‘Ladies’ City Mission’, Age, 12 July 1859; Waterhouse, Going Forward in Faith, p. 22.

[26] Ragged School Union Magazine, Vol. 1, Partridge & Oakley, London, 1849, pp. 55–56.

[27] Ibid.

[28] O’Brien, Philanthropy and Settler Colonialism, pp. 2–9; Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987, pp. 80–81.

[29] EAG Clarke, ‘The Early Ragged Schools and the Foundation of the Ragged School Union’, Journal of Educational Administration and History, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1969, p. 23.

[30] Annual Report of the Ragged School Union, no 13, 1857, p. 6.

[31] Clarke, ‘Early Ragged Schools’, p. 16; HW Schupf, ‘Education for the Neglected: Ragged Schools in Nineteenth-Century England’, History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 2, Summer 1972, p. 163.

[32] Chris Murray, ‘The Ragged School Movement in New South Wales 1860–1924’, MA thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, 1979, pp. 150–154.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Otzen, ‘Charity’, p. 42.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Journal of Joseph Greathead, 10 October 1854, pp. 55–57, State Library of Victoria, Manuscripts Collection, MS 9851.

[37] Otzen, ‘Charity’, p. 93.

[38] Ibid.

[39] ‘The Hornbrook Ragged School Association’, Age, 9 September 1864.

[40] Stuart Piggin, ‘Australian Anglicanism in a World Wide Context’, pp. 203–207.

[41] Technically, the school sat on the eastern boundary of Collingwood and Fitzroy. Karen Cummings refers to the school as being located in what is now Fitzroy, however Hornbrook and her ladies committee at the time defined the schools location as Collingwood. See Karen Cummings, Bitter roots, sweet fruit: a history of schools in Collingwood, Abbotsford and Clifton Hill, Collingwood Historical Society, Abbotsford, Victoria, 2008, p. 193.

[42] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, Melbourne, No. 1, 1863, p. 4. This and other volumes of the HRSA annual reports cited below can be found in the State Library of Victoria, Rare Book Collection.

[43] Ibid.

[44] ‘News of the Day’, Age, 4 March 1863, p. 4.

[45] ‘News of the Day’, Age, 7 January 1863, p. 4.

[46] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, No. 1, 1863, p. 12.

[47] ‘Rules’, in Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, No. 3, 1865, p. 6.

[48] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, No. 1, 1863, p. 10.

[49] Otzen, ‘Charity’, p. 93.

[50] Roslyn Otzen, ‘The Door-Step Evangelist’, in Davison, Dunstand and McConville (eds), The Outcasts of Melbourne, p. 115.

[51] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, No. 1, 1863, p. 4.

[52] Otzen, ‘The Door-Step Evangelist’, pp. 115–118.

[53] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, Nos 1–3, 1863–1865, pp. 1–5 in each report.

[54] Ibid.

[55] LJ Blake (ed.), Vision and Realisation: A Centenary History of State Education in Victoria, Vol. 1, Education Department of Victoria, Melbourne, 1973, p. 155.

[56] Amber Evangelista, ‘Schooling Melbourne’s “wretched Little outcasts”: Evangelicalism and the Hornbook Ragged Schools’, Honours thesis, Monash University, 2015.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, No. 1, 1863, p. 19.

[62] Ibid., Nos 1–2, 1863–1864, pp. 19–20 in both reports.

[63] Ibid.

[64] PROV, VPRS 10300/P1 School Files (Non-Government schools), Unit 2, School No. 86.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] ‘The Hornbrook Ragged Schools’, Argus, 1 September 1863.

[68] PROV, VPRS 10300/P1, Unit 14, School No. 815.

[69] PROV, VPRS 1183/P0, Reports of Royal Commissions, Select Committees and Boards of Inquiry, Unit 11, Report of Royal Commission on Public Education with Appendices 1877–1878, p. 10.

[70] Ibid.

[71] ‘Hornbrook Mission School’, Argus, 29 March 1912, p. 6; Community of the Holy Name (Melbourne, Vic.), Esther, Mother Foundress of the Community of the Holy Name, Community of the Holy Name, Melbourne, 1949, p. 76.

[72] PROV, VPRS 10300/P1, Unit 14, School No. 815.

[73] Ibid.

[74] PROV, VPRS 3181/P0 Town Clerk’s Files, Series I, Unit 862, Item 1895/4057.

[75] Esther, Mother Foundress of the Community of the Holy Name, p. 76.

[76] PROV, VPRS 10300/P0, Unit 13, School No. 748.

[77] Ibid.

[78] PROV, VPRS 640/P0 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 766, School No. 1192.

[79] ‘The Gospel Hall State School’, Argus, 25 August 1876, p. 7.

[80] John Carmichael, The Working of the Education Act, in the Young Victoriaseries, No. 2, George Robertson Press, Melbourne, 1875, pp. 3–10.

[81] ‘Ragged Schools: By a Vagabond’, Argus, 23 January 1876, p. 4.

[82] PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Unit 766, School No. 1192.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Ibid.

[87] ‘News of the Day’, Argus, 14 September 1869, p. 4; Evangelista, ‘Schooling Melbourne’s “wretched Little outcasts”‘, pp. 29–33 .

[88] John Stanley James, The Vagabond Papers, George Robertson Press, Melbourne, 1877, p. 158.

[89] Ibid.

[90] Ibid.

[91] ‘News of the Day’, Age, 7 January 1863.

[92] Ibid.

[93] Annual report of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, No. 2, 1864, p. 3.

[94] Ibid., No. 3, 1865, p. 2.

[95] Ibid., No. 2, 1864, p. 3.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples