Last updated:

Refereed articles

Jill’s short, tragic life in Victoria’s institutions, 1952–1955

Expand SummaryThis article uses a range of sources in the public domain to tell the story of ‘Jill’, a state ward in Victoria whose experiences in institutions attracted an enormous amount of public attention between 1952 and 1955. Jill’s story became a vehicle for heated debates about the child welfare system, during a period of considerable tension and conflict that preceded significant reform in Victoria. The representations of Jill in the media, and the consequent public interest in her case, led to the creation of records that illuminate how ‘female delinquents’ were regarded, and dealt with, by authorities in the 1950s. Jill’s story demonstrates the difficult transition from a child welfare system that heavily relied on the church and charitable sector, towards a new system with more involvement and oversight from government departments, and the input of ‘professionals’ from the social work, psychology and criminology sectors. There have been many scandals and inquiries in the history of child welfare in Australia, however the ‘Jill’ story is unique in its focus on this young woman, rather than general policy issues or conditions within a particular institution. Ultimately, this tragic story demonstrates that the system in Victoria failed to help Jill, and the public interest in her plight was limited.

The Victorian Lands Department’s influence on the occupation of the Otways under the nineteenth century land Acts

Expand SummaryBy the time Victoria’s Cape Otway Forest was opened up for settlement under the land selection Acts of the late nineteenth century, the Department of Crown Lands and Survey (colloquially known as ‘the Lands Department’) had had administrative control over land selection in the colony for about twenty years. Even though numerous land Acts had been enacted and amended by the Victorian parliament since 1860, and a Royal Commission in 1878–79 had examined the flawed outcomes of the 1869 Act, the land Acts of 1884 and 1890 proved to be a disaster for those who took up forest land in the Otways. Research on the nineteenth-century land Acts has largely focussed on the politics surrounding the legislation and the struggles of the selectors in poor country, rather than examining the role that the Lands Department’s administration played in the success or failure of the people on the land. How did the Lands Department respond to the mess unfolding in the Otways? A close examination of the department’s records shows that in the beginning it clung tightly to the letter of the legislation before gradually revising its decision-making to take account of the conditions encountered on the land. The papers held by Public Record Office Victoria reveal how and why the Lands Department came to ignore some central tenets of the legislation; they also expose the mechanisms used by the department’s officers to support those it regarded as bona fide land selectors.

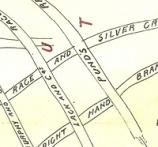

And complex mining landscapes on the Victorian goldfields

Expand SummaryPROV holds a remarkable collection of maps prepared by mining surveyors in the nineteenth century. The maps record water race networks created by alluvial gold miners, who needed large volumes of water to wash gold from the earth. These mining water systems were often very extensive, winding for miles through the hills to divert water to mining claims. The Beechworth (Ovens) goldfield was an important centre of alluvial mining in colonial Victoria and it was here that the most complex water networks were created. Many of the races and dams built by miners are preserved in goldfields landscapes today. We have integrated historical PROV maps of water races at Beechworth into a geographic information system (GIS) to analyse and understand the location and extent of historical water networks. This combination of historical maps and digital technology offers a powerful new tool to help understand the relationships between competing water users and the changes they brought to colonial mining landscapes.

The rise of Melbourne’s Ragged School system

Expand SummaryThe responses of Melbourne’s philanthropists to increasing levels of poverty and illiteracy among the urban poor in the late Nineteenth Century are well documented. However, studies of Melbourne’s early charity movements often view the movements through a local and secular lens, and the links between charity movements in Melbourne and Britain are yet to be thoroughly explored. Similarly, most histories of Melburnian charities give little attention to their religious roots, although as in Britain these were extensive. One important Melbourne charity, the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, has not received any significant attention and its international and religious roots have not yet been explored. My article examines the motivations and nature of this association, which provided free schooling to Melbourne’s destitute children, from as early as 1859. It does so in order to demonstrate how strongly British Evangelical charity movements influenced those in Melbourne. Specifically, through an in-depth study of the Hornbrook Ragged Schools I aim to demonstrate how British Evangelical charity movements directly influenced the establishment and management of Melbourne’s charity movements. Drawing attention to new sources including school registration files and annual reports, this article provides a short history of the Hornbrook Ragged School Association, and case studies of Hornbrook Ragged Schools in the ‘Little Lon’ district, Collingwood and Prahran. In doing so it documents the influence the British Evangelical charity movement exerted over one of Melbourne’s most popular charities and aims to situate Melbourne’s own unique Ragged School movement in an international and ideological context.

The role of Bundoora Homestead as a repatriation mental hospital 1920–1993

Expand SummaryBundoora Homestead is an ornate Queen Anne style Federation mansion used today as the public art gallery for the City of Darebin. Surrounded by a manicured lawn, River Red Gums and a residential housing estate, it is one of only three remaining buildings of the Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital that accommodated patients suffering from psychological trauma resulting from the theatre of war.

Since its closure in 1993, knowledge of the hospital period had largely faded from living memory. Patient records were transferred to Victorian government departments and the Urban Land Authority cleared the site, and only with fast action by the Preston Historical Society, City of Darebin and La Trobe University, was the homestead saved from demolition. In the year 2000, a grant from the Commonwealth Government Federation Fund allowed for restoration of the building to its pristine condition as it was in the Smith family era (1899–1920), and in 2001, Bundoora Homestead Art Centre opened to the public.

This paper reveals the significant role of Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital in the care and management of ex-servicemen who returned to Australia initially after Word War I (1914–1918) in 1920, World War II (1939–1945) and later conflicts. It will outline how the homestead became a mental health facility; it will discuss case studies of some of its patients, and will note the impact of the discovery and application of lithium by Dr John Cade at the hospital in the late 1930s.

The soldier settlement on Ercildoune Road

Expand SummaryThis article will contribute to the wider academic debate on the uses of ‘failure’ and ‘success’ to describe soldier settlement in Victoria after World War I. The wider historiography emphasises the common factors that brought about a failure to live up to wider national ideals, economic objectives, and social expectations. However, most scholars neglect an investigation into the other aspects of the lives of soldier settlers which could be described as a success. Through the case study of the Ercildoune Road soldier settlement in Burrumbeet, Victoria, it will be shown how the farmers could be described as a success from both a personal and local perspective. The evidence for this contention is largely based on archival sources found at Public Record Office Victoria. Given the importance of context, a case will be made for caution in the use of ‘failure’ and ‘success’ as evaluative tools for constructing narratives on soldier settlement.

Mothers of Aboriginal diggers and the assertion of Indigenous rights

Expand SummaryThe article examines letters written by mothers of Victorian Aboriginal diggers protesting efforts by the Board for the Protection of Aborigines (BPA) to restrict their access to their sons’ military allotments. The women objected to the BPA’s interventions to persuade the Federal Department of Defence, which paid the funds, to cease payments on the grounds that the Aboriginal mothers were recipients of Victorian state funding as residents of reserves. The interchanges of the women with BPA officials afford further evidence of their continuing forceful defence of their rights despite the power imbalances in their relations with the state.

Forum articles

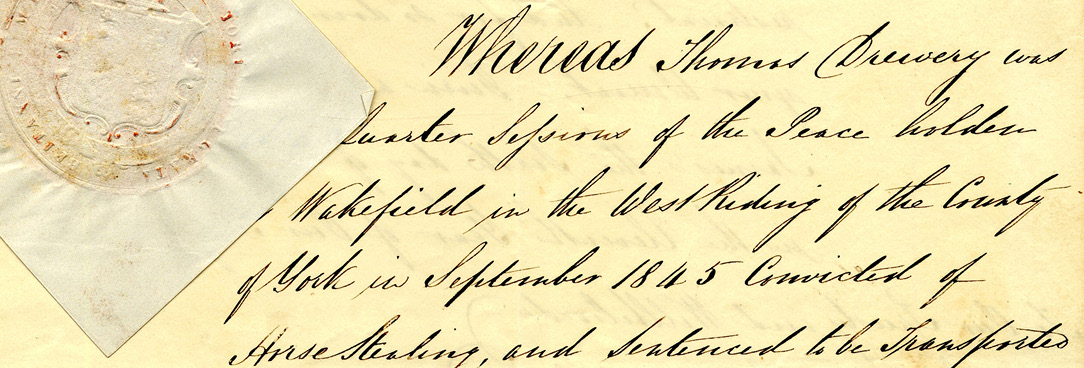

Thomas Drewery, chemist and exile 1821-1859

Expand SummaryDuring my family history research I stumbled upon an intriguing story of an innocent Pentonvillain named Thomas Drewery. Thomas was wrongly convicted and sentenced to transportation. The correspondence clearly showed he never accepted his conviction or the injustice that had befallen him. This article explores the story of his fight to be reunited with his family. Among the records held at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) is VPRS 2877 Inward Registered Correspondence I [Land Branch], which includes correspondence discussing the vexing question of payment for his family to come to Melbourne. Thomas had assistance from several quarters; one was a stranger, a convict serving ten years in Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania). In Melbourne Thomas arrived as an exile, and found work in his profession as a chemist. He established a business in Elizabeth Street, served as a councillor and went on to manage a hotel. He succeeded in reuniting his family. In the correspondence I discovered the harsh British legal system and the devastating effect it had on Thomas and the bleak circumstances that it inflicted upon his family. Through my research into these invaluable PROV resources, Thomas’s story can now be told.

A builder of early West Melbourne

Expand SummaryThis paper gives an account of the life and work of John Jones (1836–1909), a Welshman who plied his skills as a stonemason and builder in inner Melbourne during the latter half of the nineteenth century. During his working life, Jones built over 40 homes, predominantly in West Melbourne, including his family home in Hawke Street. Primary historical records available at Public Record Office Victoria have been used to trace the surviving homes built by Jones and to map their location. The earliest surviving property is a simple brick and stone cottage in Hawke Street constructed in 1873. More recent properties built between 1877 and 1889 were generally larger two-storey residences characteristic of the late Victorian era. In his last major project in 1892, John Jones was one of two contractors to build St David’s Hall at the rear of the Welsh Church in La Trobe Street, Melbourne. The hall has served the Welsh Church community in Melbourne for over 120 years and in the 1890s was used as a medical clinic for women, which later evolved into the Queen Victoria Hospital.

A public hearing of private lives

Expand SummaryAmid ANZAC commemorations and stories about the eagerness of Australian men to join World War I, it is rarely reported that approximately 45% of eligible men did not enlist and more than 87,000 men actively sought exemption from military service. Acknowledging these statistics, and the experience of these men, does not diminish respect for those who served or for the sacrifices they made. Instead, it allows a more accurate perspective from which to view their actions. This article explains the historical context of exemption court records and explores how these records can help illuminate the experience of the men who stayed at home. Those seeking a deeper understanding of the social context of military service can consult exemption court records that are freely available at Public Record Office Victoria. The records document men who sought exemption from military service, their reasons for doing so and the decisions of the exemption courts.

Mental illness and the campaigns for admission to Mont Park Military Hospital

Expand SummaryIn 1918, World War I ended and Australia’s social landscape was forever changed. The war took away the nation’s innocence, and filled its people with sorrow and despair during and after the war. The cheerful enthusiasm and strong patriotism for King and Country had been sorely tested, and for many, would never be the same. The families of repatriated soldiers rejoiced at their homecoming, yet in time, some would despair at the changed man who had returned to them. This short piece is from my 2013 honours thesis, where I examined correspondence relating to returned soldiers with ‘shell shock’ and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and their requests to be treated at Mont Park Military Hospital rather than the state-run ‘insane’ institutions. It also discusses how the Red Cross Society was instrumental in fundraising, and providing support for soldiers and their families, during and after the war. The insightful works of Marina Larsson were instrumental in engaging my interest in the compelling, ‘other’ story of soldiers who returned from World War I.

Research journeys

‘Who says you can’t change history?’ shows the intensely personal quest to break down a massive brick wall, my family history mystery of 120 years. Born in 1892 in Carlton Victoria, my Nana Beatrice McMahon nee Hughes (but actually Watson) died at 59 years never knowing her birth family. The mystery continued throughout my mum’s life of 50 years and overshadowed my life for more than 50 years until 2011. Resuming the search that my mum had started and that I shared with her before her too-early death, has allowed me to feel closer to her than ever. Added to that reconnection with my deceased mum, came a radical u-turn after my old hometown of Melbourne had progressively lost all real sense of my birth family and belonging for me over 30 years; now this extensive research has breathed new life into my hitherto jaded hometown. My childhood suburbs now had several more new addresses that connected to my family, and some other suburbs and Victorian country towns now became newly significant to my past and my present. And of course with the houses came many new relations to share with, and the opportunity for me to present them with valuable untold stories of our shared forebears. This uncovering of a huge long-lost family shows how Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) records in the last four years have contributed immensely to my research and almost single-handedly uncovered a whole family tree. The crafting was not of just the static names in their little boxes that make up the family tree graphic. Family scenarios unfolded, and were plumped up when combining various records to show different aspects of my ancestors’ lives. Cross-checking with records of other family members constructed whole family vignettes. My family history research yielded hundreds of records, often ingrained with more than a hundred years of dust. The records also showed up as multi-folded pages, often thick sheets and sometimes ‘paper thin’ like crepe paper. The folds were only annoying when it came to photographing them! PROV played such a vital role in my family history because my Watson family mystery has no family folklore passed down, no living descendants to chronicle the generations beyond my own and that of our grandparents. What surprised me when I finally met so many second, third and fourth cousins, was that I was not the only one left in the dark. Pen-inked words and old typewriting became the life-line to my large ancestral Watson family. Once I got comfortable with the peppered legal jargon of wills and probates, numerous ward registers, mental asylum records, court cases, watchhouse records and inquests, I was able to glean vital clues. Family dynamics flavoured several wills. Insights into Victorian history seeped through an often quirky turn of phrase. PROV has provided me with so much adventure and incredible surprise turns, even in connecting with other families who fostered my previously unknown great aunts. I love to share with people the vibrancy of PROV, not the staid perception that many people may have. This article is dedicated to my mum, Irene Mary Keown nee McMahon, 28 October 1930 – 16 July 1981

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples