Last updated:

‘The families of World War I veterans, mental illness and the campaigns for admission to Mont Park Military Hospital’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Janet Lynch

In 1918, World War I ended and Australia’s social landscape was forever changed. The war took away the nation’s innocence, and filled its people with sorrow and despair during and after the war. The cheerful enthusiasm and strong patriotism for King and Country had been sorely tested, and for many, would never be the same. The families of repatriated soldiers rejoiced at their homecoming, yet in time, some would despair at the changed man who had returned to them. This short piece is from my 2013 honours thesis, where I examined correspondence relating to returned soldiers with ‘shell shock’ and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and their requests to be treated at Mont Park Military Hospital rather than the state-run ‘insane’ institutions. It also discusses how the Red Cross Society was instrumental in fundraising, and providing support for soldiers and their families, during and after the war. The insightful works of Marina Larsson were instrumental in engaging my interest in the compelling, ‘other’ story of soldiers who returned from World War I.

Introduction

World War I (also known as the Great War) ended with the Armistice in November 1918, after which time the Australian servicemen and women who survived the conflict returned to civilian life through demobilisation and repatriation. This was indeed a ‘long war’, with its effects lasting well beyond 1918, as was shown by the number of veterans who went on to suffer debilitating health problems over subsequent years. The government had optimistically planned for the short-term rehabilitation of injured soldiers, and initially focussed its resources on the most severely disabled and those who were displaying physical signs of illness at war’s end. Repatriation Minister Senator Millen delivered a speech to the Australian Senate in 1918, in which he described ‘totally and permanently incapacitated’ soldiers as ‘those who are bed-ridden and those who are paralysed, and who will always require nursing and medical attention’.[1] However, the government had not foreseen that the demand for hospitalisation of mental illnesses among veterans would escalate, in an era when mental illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were poorly understood.

Military ‘mental’ hospitals were swamped with requests for admission by families, and even by soldiers themselves, such as EW Harrison who was desperate to be treated at Mont Park Military Hospital. At the time, civilian ‘insane’ asylums were considered inferior to the military hospitals, and the status of a returned soldier who was accepted for medical attention in a military facility, afforded a man a higher quality of care and general acceptance in society. Of most importance in the care of disabled soldiers and their families was the Red Cross Society. Its many tasks included the staffing of military hospitals and convalescence homes with nurses and volunteers, ongoing fund-raising efforts, as well as providing various items like gramophones, records and socks; small, yet important items to the patients. The struggle of disabled veterans has been brilliantly re-told in Marina Larsson’s book, Shattered Anzacs, a moving story of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) soldiers who returned home from the war suffering disabilities or ill-health. These veterans were raised in a time when bravery and stoicism dictated that the harshness of war was not discussed, and mental illness was especially a taboo subject in society, and little understood by doctors. I researched some of the letters of soldiers and their families, in which I read their pleas with doctors for admission to Mont Park Military Mental Hospital, a place where they believed returned soldiers would be treated with care and dignity.

The struggle of disabled soldiers who returned home

After war broke out in Europe in 1914 and Britain made a ‘call to arms’, Australia wasted no time in recruiting and deploying AIF soldiers to assist the ‘mother country’. The Australian Prime Minister who replaced Andrew Fisher during the war was William Morris (Billy) Hughes. He described the war as a ‘grave national peril’ and ‘a threat to our existence’ even though it was fought 12,000 miles away.[2] Newspapers added to the community’s fear by emphasising that a British defeat would spell ‘national extinction’ for Australia, which therefore needed to take all possible precautions against the German enemy.[3] By war’s end in 1918, the Chief Army Medical officer, Colonel AG Butler, tabled in his report that Australia had suffered a loss of 59,342 lives, with the number of ‘invalids’ swelling to over 103,897.[4] Apart from those disabled men with missing limbs, deformed faces and bodies, there were many more with minds permanently affected by the carnage and constant shelling of trench warfare, of which no one at home could ever understand. The survivors tucked away these memories in the back of their tormented minds and tended not to speak of their experiences. The most severely affected ‘shell shock’ cases were treated in the large military ‘mental’ hospitals like Mont Park, however over time the demand for inpatient services exceeded the resources.

The diagnosis of shell shock had been recognised by the British Army by the end of 1915 as the ‘shock’ of being buried by the earth or debris from a shell explosion, and was later associated with ‘neurasthenia’ or ‘nervous breakdown’ after battle, which displayed various symptoms such as confusion, stupor, amnesia, tremors, paralyses, anxieties or disablement.[5] In Australia, ‘shell shock’ had been seen as a disability affecting the serviceman’s morale, which could be alleviated through his return to work, and the Senior Medical Officer of the Repatriation Commission in Sydney had remarked in the post-war years, that ‘the rate of insanity amongst ex-soldiers now … is not excessive’.[6] In the early twentieth century, authorities had little understanding of how psychological illnesses like PTSD could develop long after the wartime experience, although later it was recognised that trench warfare had traumatised many soldiers for the remainder of their lives.

Shell shock and post-traumatic stress disorders among veterans

Soldier SG of the 14th Battalion, AIF, was buried by a shell explosion at Gallipoli on 25 April 1914, and was evacuated to hospital in Egypt suffering from shell shock and chest injuries.[7] He was later discharged from the army as medically unfit, and was in and out of military hospitals for more than eleven years. When SG was examined by Dr Catarinich, the Medical Officer-in-Charge of the Repatriation Mental Hospital at Bundoora in 1925, he expressed suicidal thoughts toward himself, murderous thoughts towards his wife, and was diagnosed with depression and severe asthma.[8] Despite his past ill-health however, in 1924 the Repatriation Department had denied responsibility for his hospital care, suggesting that his condition was caused by alcoholism rather than war service.[9] However, Dr Catarinich and Dr Jones, the Inspector General for the Insane, Lunacy Department of Victoria, advocated to the Repatriation Department to have this decision overturned, arguing that his condition had been caused by SG’s wartime experiences.[10]

The average age of the disabled men who returned home after the war was around twenty-seven.[11] This impacted heavily on the structure of local communities, as often there were fewer young, able-bodied men of marriageable age who could take over working farms from ageing parents. In addition, many parents had to take on the additional burden of caring for disabled sons as well as maintaining their farms. Catherine Smith of Casterton wrote to Dr Jones, the Inspector General of the Mont Park Military Hospital, about her son William in 1927, observing ‘… he is not normal. I doubt if he ever will be … he is now trying his best to work up a little bee farm: so that remains to be seen, how he gets on … his father is 75 years … I am 65 years … he is now over 40 and his life is blighted’.[12] Many soldiers like William Smith, who was wounded in France in 1918, also suffered from a physiological illness caused from battlefield experience, which was less recognised in the post-war period as a disability, compared to an identifiable wound or disease.

Advocating for veterans at Mont Park Military Hospital

During the post-war years, as more servicemen began to display psychological disorders, families made regular appeals for their sons and husbands to be admitted, or kept longer at the military ‘mental’ hospitals such as Melbourne’s Mont Park Military Mental Hospital.[13] In this period, the stigma of mental illness or ‘insanity’, which was seen to be caused or aggravated by an underlying hereditary condition, was a source of shame for many families.[14] As such, they did not want their shell shocked soldiers to be classed as weak or insane, and advocated for them to be treated in a repatriation hospital as the conditions, treatment and staffing of these institutions was considered to be superior to the state-run ‘insane’ asylums.[15] Care in a military hospital provided afflicted veterans with access to specialised medical staff, superior food, entertainment and outings organised by volunteers such as the Red Cross Society (RCS), as well as endorsing them as ‘mentally afflicted heroes’.[16]

In the 1920s, due to over-crowding, the Inspector General for the Insane at Mont Park and the Repatriation Department, Dr Jones, had attempted to transfer 75 patients from Mont Park to Victorian state-run institutions, and word spread quickly among soldiers’ families. An emergency meeting was called by the Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Fathers Association of Victoria (Fathers Association) with the acting repatriation minister. Following their vigorous opposition to this decision, the transfer was stopped.[17] Our Empire later reported that in Parliament the Member of the House of Representatives for Corio, Mr Lister, asked the repatriation minister why the department and the Inspector General for the Insane had signed the authority to transfer patients, and he was advised that it was due to the pressure of space, as the number of soldier ‘mental cases’ had exceeded all estimates.[18] During the 1920s the demand to be accommodated in one of the 130 repatriation beds at Mont Park and its adjoining convalescent centre at Bundoora, which housed ‘quiet’ nerve cases, stretched the government’s resources under the pressure of bad economic times.[19]

As shell shock was thought to be a temporary condition which would improve with good rest and patient care, the Repatriation Department had not planned for the new, prolonged and recurrent hospital admissions for ‘shell-shocked’ veterans; later many of these illnesses would be recognised as PTSDs.[20] The Fathers Association admonished the decision of the Inspector General for the Insane, and said they would join together with Women’s organisations to fight such moves which they described as ‘scandalous treatment of our war-strained soldiers’.[21] Such was the resolve of families that their soldier-boys have the best available treatment and care, which generally they were unable to give them at home, that they quickly formed protest groups and insisted that the Australian Government maintain its commitment to care for disabled and ill soldiers. In contrast, Dr Jones complained in a letter to the repatriation doctor that it was only in Victoria that soldier ‘mental’ cases were prevented from being transferred to civilian institutions due to the interference of the Fathers Association, and that the military mental hospital was originally meant to be used for shell-shocked soldiers but that use had come to an end.[22] He preferred that they retain around 50 or 60 ‘quiet’ cases whom he would select to stay there and transfer the remaining 60 or 70 patients, that he described as ‘fairly troublesome and chronic cases’.[23] He added that the views of the Returned Soldiers’ Association, which asserted that the Repatriation Department should build a special mental hospital for all forms of mental disorder was ‘extravagant’, as in a few years’ time the new accommodation would be empty, and that if the association succeeded with this demand, it would ‘turn its attention to other states’.[24]

Larsson has observed that middle-class, educated families were over-represented in correspondence written to doctors at the military hospitals.[25] They were more powerful advocates, who were able to utilise their capabilities by networking and campaigning relentlessly, thereby negotiating to have their relatives admitted to military institutions like Mont Park. Many examples of their articulate letter writing can be found in the Mont Park archives, and in contrast there is little record of those who may have made verbal requests for an admission or transfer to Mont Park.[26]

Returned soldier LGB, who had suffered from melancholic depression as a result of active service, had resumed his teaching career but then ‘lost confidence in himself’ and was later admitted to Callan Park Mental Hospital in New South Wales (NSW) in 1923.[27] Dr Jones advised Dr Wallace of Callan Park that the patient’s mother had requested he be moved to the Mont Park Military Mental Hospital so that his family could visit him more frequently. In response, Wallace stated that LGB’s brother in NSW had been taking him out for visits, but lately appeared to have become afraid of the patient, and had ‘given up on taking him out’.[28] A soldier’s wife, Mrs HB of Upwey wrote to Dr Jones in 1928, requesting that her husband be kept at Bundoora longer, as ‘he still has the idea I am afraid of him’, adding that while he was there his health was improving.[29]

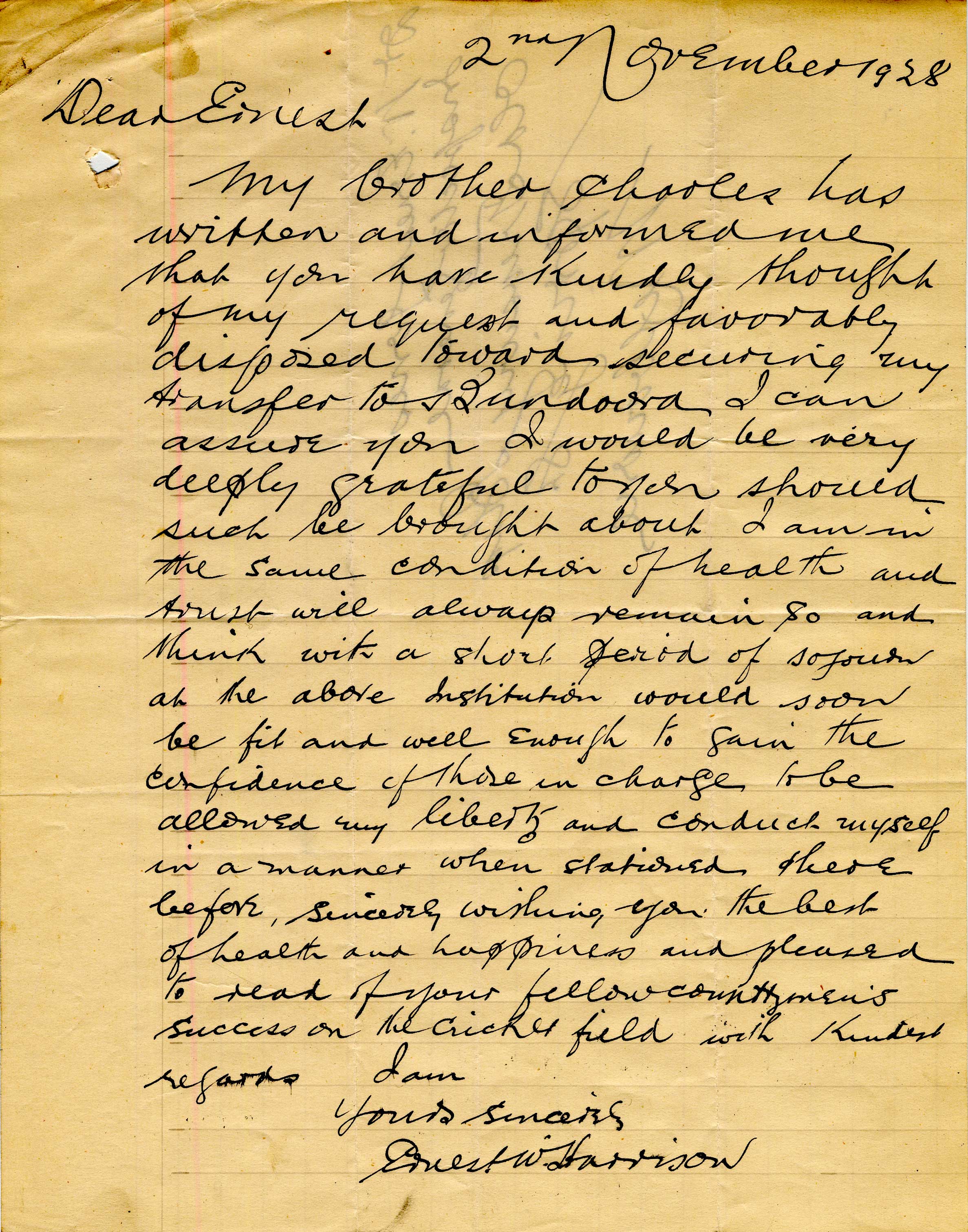

EW Harrison a bank clerk from Tasmania, who had been the first captain of the South Launceston Cricket Club, and described as a ‘capable all-rounder, experienced and respected’, enlisted in the army in 1915 when he was forty years old.[30] In the first season of the cricket club in 1907–08, he had made 719 runs including 4 centuries, at an average of 79.88, winning the association’s batting average, which he won on another four occasions.[31]

Harrison had undertaken active service in France and was promoted from sergeant to lieutenant. He suffered permanent deafness from a shell explosion at the Somme battlefield.[32] He was later classified as medically unfit and returned to Australia on board the hospital transport ship Ulysses in 1919. This was the extent of known injuries listed in his service record, which also noted that his general health was good. Therefore it is uncertain when he began to suffer from a psychological illness which caused him to be admitted to the Mental Diseases Hospital in Tasmania.[33]

In December 1925, the Repatriation Commission had advised Dr Jones, ‘While the Department is quite willing to do everything possible to find employment for patients who recover, I am afraid it will prove a very difficult matter indeed to place suitably Harrison, whom I know well’.[34] Harrison’s determined effort for a transfer to Mont Park Military Hospital in Bundoora from the hospital in New Norfolk, Tasmania, was well documented by doctors in both states.

Subsequently, in response to a letter from Harrison’s brother Charles, Dr Jones remarked, ‘I think that you fail to realise our difficulties in dealing with your brother, it is extra-ordinarily difficult to put him off … He is better now than he has been for some time, but we all suspect the presence of auditory hallucinations … I can assure you that your brother is having all the attention and consideration that it is possible for a limited medical staff to give him’.[35] Despite concerns from doctors regarding his fragile mental state, Harrison continued his writing campaign for a transfer, expressing himself quite articulately.

In 1928, Harrison was still pleading with Dr Jones for a transfer, stating that he was unfortunate to be an inmate of the New Norfolk Asylum and that he needed help from Dr Jones to obtain a transfer to Bundoora. He advised that he had sought assistance from his brother in his endeavour, and felt frustrated at his inability to achieve a result so far. He declared that his life ‘was a damned bugbear’, as prior applications to the Returned Soldiers’ Association in Hobart and others (not named) had not brought him a satisfactory result. He again pleaded with Dr Jones to support his transfer and also asked the doctor to visit him when he was next in Tasmania.[36]

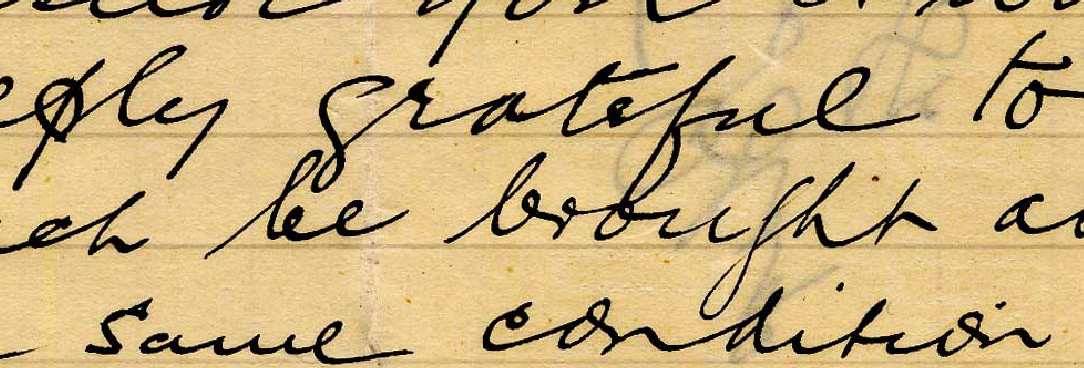

Previously, Dr Aitken, the Tasmania doctor treating Harrison, had written to Dr Jones regarding the patient’s recent ‘suicidal tendencies and obsession with being transferred to Bundoora’, adding that he was ‘at a loss at what to do with him’.[37] Dr Aitken had responded to his brother Charles’s request for a transfer to Mont Park, stating he was still having ‘auditory hallucinations’ and if he was transferred to Melbourne there would be a risk bringing him by boat ‘due to his suicidal tendencies’.[38] Despite his lack of success, Harrison was not deterred and he continued to write to authorities requesting a transfer. In another letter to Dr Jones in November 1928, while still hospitalised at the New Norfolk Asylum, he again pleaded his case to be transferred to Bundoora, thanking the doctor in advance and emphasising that his brother had requested that this transfer take place. He remarked that a ‘stint at Bundoora would assist his rehabilitation’, and he wished the doctor the best of health and happiness, even adding that he had read of the success of his fellow countrymen, the English, on the cricket field.[39] Harrison also asked Dr Jones if ‘it would cause offence if he wrote to the Red Cross Society requesting a donation to supply returned men with badly needed socks, towels and soap, as well as flannel shirts and underwear’, explaining that he only mentioned this, as he had seen men without socks and shirts at the facility.[40] It is unclear whether Harrison ever succeeded in his endeavours to be relocated to Mont Park, however he passed away in Tasmania at the ripe old age of 94.

The founder of the Australian Red Cross Society, Lady Helen Munro-Ferguson, wife of the Australian Governor-General, had been a member of the British Red Cross Society (BRCS) in Scotland. The Australian branch was established in response to the outbreak of war. When Lady Helen arrived in Australia in May 1914, she possessed a detailed knowledge of the Red Cross movement in Great Britain.[41] The BRCS was loosely associated with the Swiss-based organisation, and in 1904 was forcibly merged with the British Aid Society by royal decree.[42] After war was declared Lady Helen cabled the colonial office in London seeking authorisation from the BRCS to form a branch in Australia which was subsequently approved.[43] Lady Helen held the office of national president for six years, defying tradition by running it like a modern-day chief executive officer (CEO).[44]

The Red Cross had extensive experience overseas during World War I providing medical goods and voluntary labour to the armed forces. This experience proved to be of significant benefit after soldiers returned to Australia.[45] Its development and management of military convalescent homes, along with medical supplies and volunteers, became integral to the Repatriation Department’s program for incapacitated soldiers; hence, they worked mutually towards restoring sick and disabled men to good health.[46] Although soldiers’ rehabilitation was the responsibility of the Repatriation Department, organisations like the Red Cross ensured that schemes and care were provided through generating the financial means for their own operations, and it also managed convalescent facilities through its formidable volunteer workforce.[47] The schemes devised by the Repatriation Department included demobilising soldiers and providing medical care, housing, sustenance, education and training opportunities.[48] The rehabilitation of disabled soldiers involved assisting men to overcome their physical impairments as well as attempting to improve their mental outlook.[49] The repatriation minister sought the cooperation of the Red Cross in each state to provide, equip and conduct convalescent homes for discharged soldiers suffering the effects of war. Many of these private homes were gifted or loaned by individuals to the society and run by the local Red Cross branch, with a payment of 6 shillings per day per patient remunerated by the Repatriation Department.[50]

Accordingly, the Red Cross Society was also involved in advocating on behalf of soldiers who were hospitalised in Mont Park Military Mental Hospital and in Bundoora, after concerns had been expressed by family groups such as the Fathers Association, about the living conditions of 100 men grouped together with ‘various stages of mental affliction’.[51] The society constantly responded to requests for provisions of items such as slippers, pillowcases, and use of a motor car, which transported patients on weekly visits to the theatre.[52] It also offered to donate additional gramophones and provided a woodwork teacher for patients’ use.[53]

Another correspondent to Dr Jones was the sister of returned soldier Jack Linton, who wrote in March 1929 expressing her surprise that he was not at the military block ‘as we understood he was to be’, and asking ‘[w]ould you be good enough to review his papers at your earliest convenience and move him to the Military Block where he rightly belongs? He has suffered from shell shock since 1917 and has been in Caulfield Military Hospital every 18 months (approx.) since his return from active service’.[54] Linton, a country boy from Maffra in Gippsland had enlisted in late 1915 and saw active service in France and Belgium. He suffered severely with trench feet, for which he was hospitalised in England, and was later diagnosed with shell shock. In April 1917 he also returned to Australia on the hospital transport ship Ulysses and was discharged medically unfit from the army on 13 December 1917.[55]

Overall, although much has been written of the terrible conditions of trench warfare in World War I and the origins of the Anzac legend, there are very few books that encompass the struggle and despair of disabled veterans and their families as depicted in Larsson’s Shattered Anzacs. Many soldiers developed mental illness years after returning home, and in addition to the many sick and physically disabled men, this placed a strain on limited post-war government resources in the lead up to the Great Depression. This article has examined some of the moving and confronting correspondence from the families of mentally ill veterans who advocated strongly for them to be admitted to Mont Park Military Mental Hospital. In addition, some patients, such as EW Harrison, were lucid enough to compose rational letters pleading their own case for a transfer.

Endnotes

[1] ED Millen, Australian Repatriation Scheme: speech, McCarron, Bird & Co., Melbourne, [1918?].

[2] Gerhard Fischer, ‘“Negative Integration” and an Australian road to modernity: interpreting the Australian homefront experience in World War I’, Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 26, No. 104, 1995, p. 453.

[3] Ibid.

[4] AG Butler et. al., The official history of the Australian Army Medical Service in the war of 1914–18, Vol. III, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1930–1943, p. 880.

[5] Ibid., Vol. III, p. 98.

[6] Ibid., Vol. III, pp. 833 and 835.

[7] PROV, VA 2846 Mont Park (Hospital for the Insance, 1912–1934; Mental Hospital 1934–c.1970s; Mental/Psychiatric Hospital c.1970s-ct), VPRS 7527/P1 Military Mental Hospital Correspondence Files, Unit 1, Item 24/2847, letter from Dr Catarinich, Medical Officer-in-Charge, Repatriation Mental Hospital, Bundoora, to Medical Superintendent, Mont Park, 31 July 1925. Here and in a number of other cases cited in this article, I have used initials to protect the identity of some individuals and their descendants.

[8] Ibid.

[9] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 24/2847, letter from WB Ryan, Deputy Commissioner, Repatriation Commission, to Medical Officer-in-Charge, Repatriation Mental Hospital, Bundoora, 18 November 1924.

[10] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 24/2847, letter from Dr Catarinich, Medical Officer-in-Charge, Repatriation Mental Hospital to Dr E Jones, Inspector General for the Insane, Lunacy Department, Victoria, 28 July 1925.

[11] Butler et. al., The official history of the Australian Army Medical Service, Vol. III, p. 889.

[12] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 27/2752, letter from Catherine Smith to Dr Jones, 3 October 1927.

[13] Marina Larsson, Shattered Anzacs; Living with the Scars of War, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 2009, p. 161.

[14] Ibid., p. 159.

[15] Ibid., pp.159 and 161.

[16] Ibid., pp. 155 and 161.

[17] ‘Treatment of “Mental” Soldiers’, Our Empire, 18 May 1921, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 9.

[18] ‘Treatment of our Mental Soldiers’, Our Empire, 18 June 1921, Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 4.

[19] Larsson, Shattered Anzacs, p. 156.

[20] Ibid., p. 210.

[21] ‘Treatment of our Mental Soldiers’, Our Empire, 18 June 1921, Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 4.

[22] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 24/2847, letter from Dr Jones to Dr Sinclair, 2 July 1924.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Larsson, Shattered Anzacs, p. 167.

[26] Ibid.

[27] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 24/2847, letter from Wallace to Dr Jones, 4 August 1925, and Item 25/1917, letter from Dr Jones to Wallace, 28 July 1925.

[28] Ibid.

[29] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 28/906, letter from HEB to Dr Jones, 10 May 1928.

[30] ‘South Launceston Cricket Club’, entry on Wikipedia, available at <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Launceston_Cricket_Club>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[31] Ibid.

[32] NAA: B2455, Harrison E W, personnel dossier, available at <http://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/230763/40>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[33] Ibid.

[34] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from Deputy Commissioner of Repatriation to Dr Jones, Inspector General for the Insane, 3 December 1925.

[35] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from Dr Jones, Inspector General for the Insane, to Charles Harrison, 21 September 1925.

[36] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from EW Harrison to Dr Jones, 23 August 1928.

[37] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from Dr Aitken to Dr Jones, circa 1925.

[38] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from Dr Aitken to Charles Harrison, circa 1926.

[39] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from EW Harrison to Dr Jones, 2 November 1928. Dr William Ernest Jones was born in Staffordshire England in 1867, and after immigrating to Victoria he was appointed Inspector General for the Insane in 1905, see ‘William Ernest Jones’ entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jones-william-ernest-6882>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[40] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/565, letter from EW Harrison to Dr Jones, 2 November 1928.

[41] Melanie Oppenheimer, ‘The best P.M. for the empire in war?: Lady Helen Munro Ferguson and the Australian Red Cross Society, 1914–1920′, Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 33, No. 119, April 2002, p. 114.

[42] Ibid., p. 115.

[43] Ibid., p. 116.

[44] Ibid., p. 108.

[45] Ibid., p. 112.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Marina Larsson, ‘Restoring the Spirit: The Rehabilitation of Disabled Soldiers in Australia after the Great War’, Health and History, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2004, p. 49.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Leon Stubbings, ‘Look what you started Henry’: A History of the Australian Red Cross 1914–1991, Australian Red Cross Society, East Melbourne, 1992, p. 13.

[51] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 28/874, letter from PN Robertson, General Secretary ARCS (Victorian Division), to the Editor of the Age, 13 March 1925.

[52] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 24/874, letter from Dr Jones, Inspector General for the Insane to PN Robertson, General Secretary ARCS (Victorian Division), 12 May 1924, letter from PN Robertson, General Secretary, ARCS (Victorian Division) to Dr Jones, 14 May 1924, and letter from J Eller, Acting General Secretary to Colonel Jones, Australian Army Medical Corps, 15 May 1925.

[53] Ibid.

[54] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1, Unit 1, Item 29/765, letter from Miss V Linton to Dr Jones, 4 March 1929.

[55] NAA: 4134, LINTON, J J, personnel dossier, available at <http://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/268685/19>, accessed 8 September 2025.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples