Last updated:

‘Lithium and lost souls: the role of Bundoora Homestead as a repatriation mental hospital 1920–1993’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Cassie May.

This is a peer reviewed article.

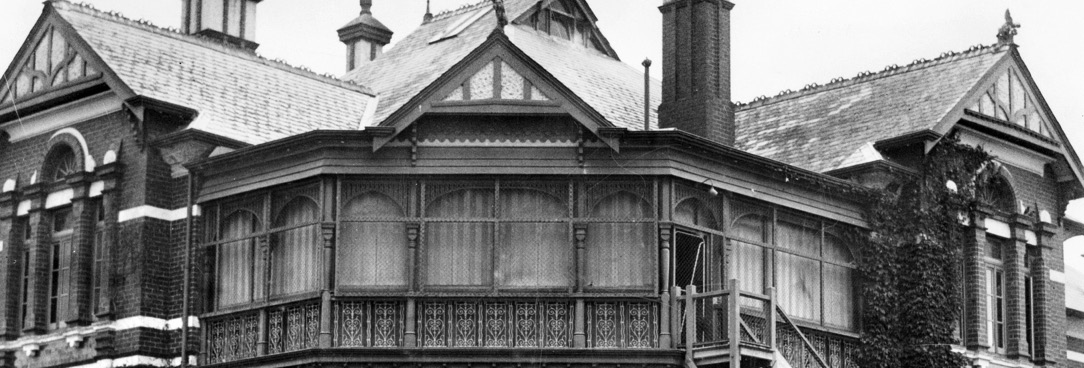

Bundoora Homestead is an ornate Queen Anne style Federation mansion used today as the public art gallery for the City of Darebin. Surrounded by a manicured lawn, River Red Gums and a residential housing estate, it is one of only three remaining buildings of the Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital that accommodated patients suffering from psychological trauma resulting from the theatre of war.

Since its closure in 1993, knowledge of the hospital period had largely faded from living memory. Patient records were transferred to Victorian government departments and the Urban Land Authority cleared the site, and only with fast action by the Preston Historical Society, City of Darebin and La Trobe University, was the homestead saved from demolition. In the year 2000, a grant from the Commonwealth Government Federation Fund allowed for restoration of the building to its pristine condition as it was in the Smith family era (1899–1920), and in 2001, Bundoora Homestead Art Centre opened to the public.

This paper reveals the significant role of Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital in the care and management of ex-servicemen who returned to Australia initially after Word War I (1914–1918) in 1920, World War II (1939–1945) and later conflicts. It will outline how the homestead became a mental health facility; it will discuss case studies of some of its patients, and will note the impact of the discovery and application of lithium by Dr John Cade at the hospital in the late 1930s.

Introduction

The Anzac Centenary marked 100 years since Australia’s involvement in World War I. It provided a poignant opportunity to question why little was known about Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital, and of the patients who were housed there for over seventy years. The exhibition Coming Home[1] was staged in late 2014 to help address this enquiry, and drew its content from public archives and the generous contributions of family members of ex-patients, retired hospital staff and the staff of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

There is a large body of existing research regarding war-related mental illness emerging from World War I, alongside broader understandings of Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD).[2] Personal perspectives about the impact of mental illness on returned soldiers has been explored in depth in Marina Larsson’s Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War.[3] Themes of family, loss and mental illness were the focus of Tanja Luckins in Australia in Madness in Australia: Histories, Heritage and the Asylum.[4] Iliya Bircanin and Alex Short have provided an informative historical survey of the immediate area of psychiatric facilities of Mont Park, Larundel and Plenty in the twentieth century in their publication Glimpses of the Past: Mont Park, Larundel, Plenty.[5] The following analysis of the history of Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital provides a window into the operations of a government institution that provided psychiatric and social support to a particular set of patients across the twentieth century.

Bundoora Park

Bundoora Homestead was built in 1899 for JMV Smith, a prominent identity in the horse breeding and racing industry. The 606 acre (245.2 hectare) property known as Bundoora Park, operated as a horse and cattle stud and was home to successful race horses and breeders including Wallace, Challenger, andPilgrim’s Progress.[6] As a fourteen room mansion and family home for Smith and his wife Helen and their four children, the building was the centrepiece of the large estate. It comprised of an entrance hall, grand stair hall with oval stained glass ceiling, a drawing room (probably converted to a billiard room by 1910), parlour, dining room and service wing. Upstairs, eight bedrooms and three bathrooms were situated off wide balconies, where the city of Melbourne could be seen in the distance; along with sweeping vistas towards the Dandenong Ranges in the south-east, and across to Mount Macedon to the north-west.

In the years before the outbreak of World War I, the Smith children married and moved away to other properties in Victoria and England. By then, JMV Smith was a senior gentleman and his health had began to deteriorate. With no options for the continuation of the business and estate within the family, in 1920, Bundoora Park was offered for sale for the considerable sum of £29,000.[7] A report to cabinet, signed by Edward Millen, Australia’s first Minister for Repatriation and Minister for Defence (1913–14), identified Bundoora Park as a prime location for the establishment of a convalescent farm.

It has become necessary to make some immediate provision in Victoria for discharged soldiers who are temporarily unemployable through disabilities due to or aggravated by war service and whom out-door occupation under suitable conditions would benefit.

By the statistics in the possession of the Department a need exists whereby epileptics, neurasthenics, heart, gas and other cases should be provided with accommodation in an institution providing out-door facilities for no less than two hundred cases at a time.[8]

The Mental Treatment Act 1915 was introduced to protect returned soldiers who became mentally ill as the result of war service from the stigma of being certified as ‘lunatics’,[9] and defined the category of military patients as those suffering from a mental disorder of recent origin arising from wounds, shock, disease, stress, exhaustion or any other cause.[10] The advantage of Bundoora Park was that it provided a dedicated place to convalesce and had open air activities including dairying, and fruit, flower and vegetable growing. It had close proximity to the services of Mont Park Hospital for the Insane in the neighbouring suburb of Macleod, and had accessibility to nearby facilities for patients, visitors and departmental officers. In May 1922, the Argus newspaper reported:

Among the thousands of cases which have been dealt with by the Repatriation department, none have presented greater difficulty than those of men who, as a result of the strain of war, have been classified on their return to civil life as neurasthenics. These men might have been shell shocked, gassed, or weakened by trench fever, and they have returned to Australia bundles of nerves, shattered and debilitated. Realising that this class of war derelict was unfitted to be turned on to the labour market to compete with normal healthy workmen, the department [is] determined to give them an opportunity of recovering their strength of body and mind.[11]

Bundoora Convalescent Farm opened in 1920 and was initially adapted for use as residential accommodation, while a number of surrounding farm buildings were converted for various hospital purposes. Six additional light-weight structures were transported from Broadmeadows Military Camp to provide a kitchen, canteen, butcher’s shop, offices and storage for groceries. As theArgus article explained,

When a man whose only difficulty is his inability to pull himself together enters Bundoora he is graded, according to his disability by Dr James, and is then given light work, such as hoeing and weeding by the overseer. At first he might be inclined to be lazy and apathetic, but gradually, as his interest is awakened, he settles down to work, and graduates through the varying stages of farm labour. Payment for work is made on a sliding scale, and each man can earn £2/10 a week, including his pension, in addition to his keep. Dr James says that the average man requires four months at Bundoora. At the end of that period the listless, nerve wracked ‘digger’ has learned how to work once again, and has been transformed into a healthy, industrious labourer, ready to take his proper place in civil life.[12]

In April 1919, a dedicated ‘military mental block’ was built at Mont Park Hospital for the Insane. The Victorian Government had purchased the Mont Park land prior to 1909 to build a self-supporting asylum as a replacement for the Yarra Bend Asylum. At the time of the purchase, an eastern part of the original Bundoora Park estate was named the Mont Park estate.[13] As the number of transfers from this ward to Bundoora continued to rise, various internal alterations were made to the homestead to alleviate the growing need for accommodation, including the enclosure of the verandahs with wire mesh and canvas blinds for extra wards.[14] On 1 May 1924, Bundoora became a dedicated Repatriation Mental Hospital for the reception of twenty-seven[15] quiet, convalescent, and manageable cases.[16] Known as A Ward, the homestead operated as an open ward, where patients were allowed to move around freely.[17]

The Australian Red Cross Society played an integral role in accommodating the practical needs of the patients at Bundoora as well as fostering their social well-being. It initially responded to a request for assistance from the Australian Government’s Repatriation Department to provide recreational equipment to the hospital, and immediately supplied a full-sized billiard table. Supplementary food items were also distributed from the society such as fresh fruit, eggs, tinned fish, and cakes. In addition, welfare packages of eiderdowns, cardigans, bed socks, scarves, caps and hot water-bags were provided in the colder months. Cricket matches, chess and card games, bingo, concerts, recitals, afternoon teas, film screenings, trips to the theatre and motor outings were frequently organised by Red Cross representatives. These events, together with the annual Christmas party and associated festivities were a constant source of enjoyment for the Bundoora veterans.

The 1930s saw a phase of expansion of the hospital; in 1933, B and C wards were built to accommodate chronic and acute cases and were later fitted with padded rooms.[18] New female nursing and domestic staff quarters[19] were constructed in 1937, along with the addition of the dining room annex to the homestead.[20] In 1938, a large double-storey D Ward, which comprised 50 beds, was opened. By the end of the decade, patient numbers totalled 238.

Wilfred Collinson

The types of disorders patients at Bundoora were diagnosed with included dementia, recurrent mania, general paralysis of the insane, insanity with epilepsy, delusional insanity, obsessional psychosis, paranoia, psychasthenia, alcoholic insanity, confusional insanity, melancholia, mania, neurasthenia and manic depression. Many were treated for extended periods of time, or became permanent residents who never regained the ability to function in society.

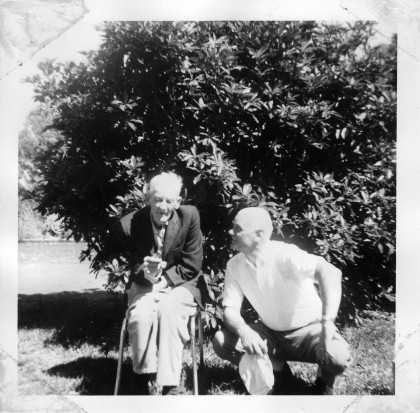

Wilfred Collinson entered Bundoora in 1937 where he remained institutionalised until his death in 1972. Signing up to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) at the age of 19, he arrived at Gallipoli in 1914, a week after the 25 April landing at Anzac Cove. He was exposed to heavy shelling at Shrapnel Gully and was hospitalised with extreme dysentery. Under the severe conditions he became affected in mind and body by the privations and rigours of the campaign. In June 1916, Collinson was posted to the 5th Division Artillery and left for France and the Western Front. During the Battle of Passchendaele, a campaign that took place between July and November 1917, he was gassed three times. Upon his return to Australia in 1919, Collinson was classified as an invalid. He was officially discharged from service, yet his medical and physical condition was recorded as fit with no incapacity or disability.

In September 1919, Collinson commenced a vocational training course and in 1920, married Carline Aminde. They went on to have four children: Richard (Dick), Albert, Patricia and June. In 1921 he gained employment with the Victorian Railways, where he worked as a fitter and turner for 15 years, during which time his physical and mental health continued to decline. In 1927 he applied to the Repatriation Commission for disability benefits in relation to his war service. He suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, coughed blood, had shortness of breath and was unable to sleep. The claim was refused and he appealed the decision, making an additional claim that his chest trouble and ‘disordered action of the heart’ was a result of exposure to weather conditions and being gassed at the Western Front. Three years later in 1930, the Repatriation Department accepted that his medical conditions were due to his war service.

By June 1936, Wilfred’s wife Carline held grave reservations regarding her husband’s state of mind. He suffered from delusions of persecution and believed that men were wandering about the house and interfering with his belongings. On 18 July 1936 he was taken by plain clothes police to Royal Park Receiving House. His mental state was assessed and as a result, Collinson was admitted to Mont Park Hospital for the Insane. The Repatriation Department refused Mrs Collinson’s request to transfer her husband to Bundoora on the grounds that his his mental afflictions, unlike his physical disabilities, were not due to his war service.

Carline was a dedicated and resilient advocate for her husband. She firmly believed that with the best medical attention he would get better. She lodged an appeal against the Repatriation Department decision, for which additional testimony was provided by a family member who stated that since 1922 Collinson had behaved oddly and was moody. Long-time friend and fellow soldier Eric Brymer also submitted a detailed account of Collinson’s decline during their war service. After consideration of the lengthy evidence, the department refused the claim. The State Repatriation Board even recommended that the appeal be disallowed and referred the matter to the Repatriation Commission. On 17 November 1936, the commission upheld the decision of the Victorian Repatriation Board and the appeal was again disallowed.

Mrs Collinson’s campaign to have her husband’s illness recognised as being the consequence of his war service and for the family to gain access to a full war pension finally proved successful on 28 September 1937. After a further appeal, the War Pensions Entitlement Appeal Tribunal overturned the Repatriation Commission decision and Collinson’s mental condition was finally accepted as being due to his war service. As a result, he was transferred to Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital on 22 October 1937, and he remained there until the time of his death, aged 77, on 4 July 1972.

Dr John Frederick Joseph Cade AO

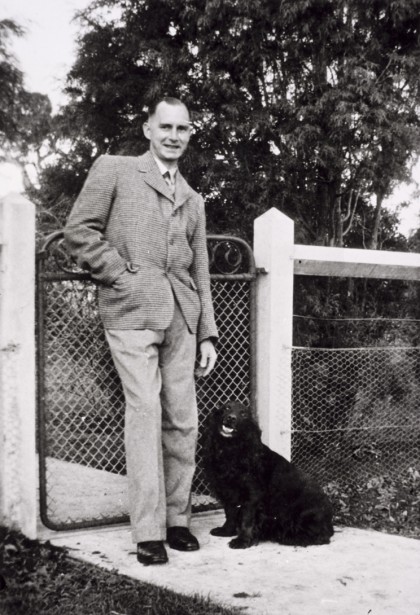

Dr Cade began his tenure at Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital in 1939 as a medical officer. Having served in the Militia [the equivalent of today’s Army Reserve] from 1935, Cade was appointed captain of the Australian Army Medical Corps, AIF, on 1 July 1940 and posted to the 2nd/9th Field Ambulance. He arrived in Singapore in February 1941 and was promoted to the rank of major in September. From February 1942 to September 1945 he suffered the privations of a prisoner of war in the Changi camp. Demobilised on 2 January 1946, Cade returned to the mental hygiene branch becoming medical superintendent and psychiatrist at the Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital.[21]

In 1947, Dr Cade pursued his suspicion that some mental illnesses were caused by metabolic disturbance. In a research laboratory in a kitchen in the unoccupied E Ward at Bundoora, he experimented with lithium carbonate as a mood stabiliser, initially on guinea pigs and himself, before administering it to a selection of unstable patients. Ten case studies demonstrating successful treatment of ‘mania’, what is now referred to as bipolar psychosis, were presented in the Medical Journal of Australia in a 1949 paper entitled: ‘Lithium Salts in the Treatment of Psychotic Excitement.’[22]

CASE II. – E.A., a male, aged forty-six years, had been in a chronic manic state for five years. He commenced taking lithium citrate, 20 grains three times a day, on May 5, 1948. In a fortnight he had settled down, was transferred to the convalescent ward in another week, and a month later, having continued well, was permitted to go on indefinite trial leave whilst taking lithium citrate 10 grains three times a day. This was reduced in one month to 10 grains twice a day, and two months later to 10 grains once a day. Seen on February 13, 1949, he remained well and had been in full employment for three months.[23]

At a time when the standard treatment for mental disorder at Bundoora was full and sub-coma insulin therapy, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) with anaesthesia and relaxants, and pre-frontal leucotomy,[24] Dr Cade’s discovery was a major breakthrough in psychiatric medicine. The methods he pioneered were later substituted by pharmacological agents, primarily the administration of lithium carbonate, chlorpromazine and Ritalin. In the following decades, lithium revolutionised the management of psychosis around the world. Cade was formally recognised for his work in the 1970s, when he was invited to be a Distinguished Fellow of the American College of Psychiatrists (1970) and received the highest honour in psychiatry, the prestigious International Scientific Kittay Foundation Award (1974). In 1976 he became an Officer of the Order of Australia.

Dr Cade was a strong advocate of the benefits of occupational therapy and supervised an expansion of the program at Bundoora when he was promoted to the inaugural position of Medical Superintendent and Psychiatrist in 1950. Until then, the hospital had been under the administrative authority of Mont Park Hospital for the Insane.[25] The expansion of the progam included the construction of two occupational therapy blocks for soft handicrafts, wood and wicker work, and a vegetable garden in the enclosure of B and C wards.[26] In 1952, Dr Cade left Bundoora to take up the role of Psychiatrist Superintendent and Dean of the Clinical School at Royal Park Psychiatric Hospital in Parkville. After an active and distinguished career, he retired in 1977.

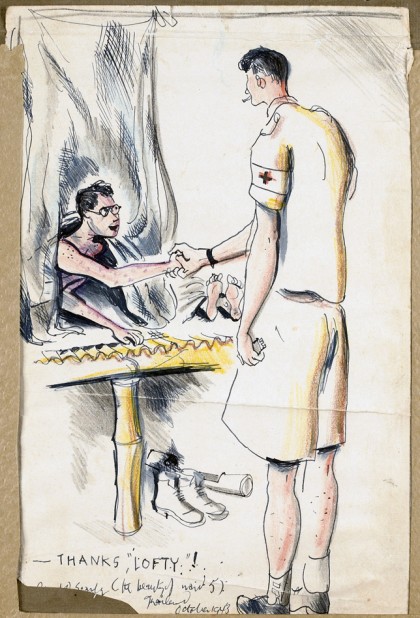

Henry ‘Lofty’ Cannon

Along with Dr Cade, Henry ‘Lofty’ Cannon enlisted in the Australian Army Medical Corps, AIF, in 1940. As a ‘surgical dresser’, he was posted to the same 2nd/9th Field Ambulance Unit and was known as ‘Harry’ to his family and ‘Lofty’ to his army mates (he was 198 cm tall). Prior to his departure in 1941, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant and married Peg, whose birthname was Mary Warwick Brown. He boarded the RMS Queen Mary in February 1941, destined for Singapore. Stationed at Port Dickson on the Malay Peninsula in September 1941, ‘Lofty’ was assigned to B company at Mersing, in support of the 22nd Australian Infantry Brigade. With the advancement of the Imperial Japanese Army, the Australian and British forces withdrew their position. Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. ‘Lofty’ and Dr Cade along with 15,000 other Australians, became prisoners of war (POWs) in Changi for the duration of World War II.

As a POW, ‘Lofty’ endured frequent bouts of malaria and dysentery as well as tropical ulcers and rheumatism. In August 1943, he was sent to Kanchanaburi camp in Thailand, as part of a medical party with ‘L’ Force, to nurse survivors of the Thai–Burma Railway working parties. One of his patients was the British artist and satirical cartoonist, Ronald Searle. Though fortunate to survive these ordeals and make it back to Australia in 1945, ‘Lofty’ was classified as medically unfit. He was officially discharged from the AIF on 5 July 1946, at which time the psychological trauma of his war experience began to manifest. He suffered residual symptoms of anxiety and constant headaches. At Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital in Melbourne, he was treated with ECT and sub-coma insulin therapy.[27] At this time, Searle wrote to ‘Lofty’ from England saying: ‘I don’t really think I ever properly thanked you for your great kindness to me “up country”[28] in that stinking hospital. I know, as you do, that you helped to save my life and made my existence under that [mosquito] net almost bearable. Believe me Lofty I’ve praised the stars that brought you to that ward many times.’[29]

By 1949, ‘Lofty’ and his wife Peg were living on a soldier settlement farm at Tresco, near Swan Hill in Victoria, and had adopted their son David. Within a few years, ‘Lofty’ Cannon’s health deteriorated. He became addicted to painkillers and alcohol, and his increasingly anti-social behaviour strained his relationship with his wife. The family left Tresco; Peg and David moved to the Melbourne suburb of East Malvern and ‘Lofty’ was admitted to Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital. In 1960, his psychiatric assessment concluded with a diagnosis of psychopathic personality and alcoholism.[30]

In a 1966 letter to Searle, ‘Lofty’ wrote: ‘My eyesight is going fast and I keep thinking I am chained again to the Burma Railway and so to set my mind at rest my own people have locked me up again.’[31] In subsequent correspondence ‘Lofty’ stated his return address as ‘Ward 6, Bundoora Repatriation Hospital’. Known also as C Ward, it operated as a closed, chronic, non-liberty ward, for patients who required constant supervision due to the severity of their psychiatric disorders.[32]

Although deeply troubled, ‘Lofty’ managed to function rationally for periods of time. It was during the late 1960s that he revived and edited the hospital newsletter. Renaming it Outlook, he wrote of the difficulties of fitting back into family life in a poem entitled ‘So You Want “Out”!’.

Unfortunately, in some cases, it doesn’t matter how– trial leave or the dream called discharge– as long as [you] get either and go to that vague place called HOME.

Be warned, be prepared for some rude shocks, for even if you have had weekend leave for years, when you come home to stop permanently you will soon find you are a stranger in a strange new place.[33]

In recognition of his military service, ’Lofty’ was awarded the 1939–45 Star, Pacific Star, Australian Defence Medal, War Medal 1939–45 and Australian Service Medal 1939–45. He remained at Bundoora until his death in 1980, aged 65.

In 1960 Bundoora accommodated 332 patients comprised of 43% World War I veterans (average age 68), 54% World War II veterans (average age 44) and 3% Korean War veterans (average age 31). By 1963, patient numbers climbed to 408.[34] In contrast to previous eras, patients organised themselves into ward groups with weekly meetings conducted by elected committees. They arranged their own social and recreational activities and took greater responsibility for their conduct in the hospital. This model of group organisation by patients for patients promoted a more relaxed atmosphere, even among the less socially competent ward groups. Additional benefits were reduced incidents of anti-social behaviour and greater participation in recreation and therapeutic programs. The number of patients granted freedom of the grounds and weekend leave, enabling them to visit their homes and relatives, also increased.

A significant change in operations occurred at Bundoora during 1961 with a division of C Ward being created to accommodate the specific treatment of mental disorders caused by alcoholism. This enabled intensive work to take place with the younger men in their rehabilitation to the extent that the ward functioned at an open ward level. This improved performance of the ward included the ability of its patients to participate in ward and garden work and simple occupational therapy projects. Additional recreational facilities were also constructed including a nine hole golf course, a bowling rink and a swimming pool for the closed wards.

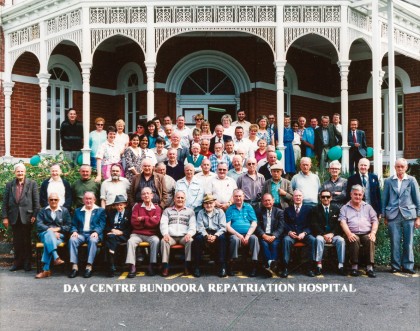

In the mid-1960s, Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital was re-named Bundoora Repatriation Hospital and the Repatriation Commission formally authorised the admission of voluntary patients. Of the 209 admissions in 1967, over 60% had problems with alcoholism, while 30% of the hospital’s total population at this time was afflicted with alcoholism.[35] With the significant increase in admissions, wards 2 and 8 were the last two structures built on site.[36] The homestead was adapted for use as a day centre where patients could access medical services and occupational therapy classes. Staff, including social workers, psychologists and case managers, moved into offices upstairs, while the downstairs areas, along with a dining room, became a place for patients to sit and chat.

In 1967 a group of four long-term patients, most likely including ‘Lofty’, developed a project in conjunction with the hospital psychologist, Mr BJ Healey, called the Book Exchange. Designed to assist in the rehabilitation and work motivation for long-term psychiatric patients, the aim was to operate a commercial enterprise in the community that could create voluntary or paid occupations outside of the hospital, and reduce the patient’s fear of contact with members of the general public.[37]

During the period 1970–1972, thirty-eight patients participated in the Book Exchange. Most had been hospitalised for a minimum of five years, ranging up to twenty-three years. Operating a shop in the Caulfield market in suburban Melbourne, the Book Exchange required substantial social skills and reasonable managerial competence. The patients travelled by public transport from Bundoora to Caulfield and back to staff the shop, Mondays to Saturdays. They categorised the books, built shelving and served customers, with nominal assistance from a group of women volunteers. An unintended outcome of the project was the generation of a consistent financial profit. These monies were paid into a special fund which assisted those in need, with preference given to families of ex-servicemen. Other gains reported by patients included: gradual reduction of anxiety about everyday life encounters, acceptance by the public (particularly young people), unexpected treatment as equals or ordinary citizens, and increased confidence, enthusiasm and self-esteem.[38] Dr Healy noted that: ‘the aimless and demoralised became more purposeful and organised in their thinking, and the depressed became more confident and less morose. Pride was taken in work and dress. Behaviour became purposeful, and regressive traits seemed to lose strength.’[39]

By the mid-1970s, very few patients under the age of fifty were accommodated at Bundoora. Voluntary admissions and discharges dominated, with annual numbers constant at approximately 300 patients, including those on trial leave. Due to the largely ageing hospital population, in 1984 the number of veterans at Bundoora fell to 154. Chaired by Dr Ian Brand, the Review Committee of the Repatriation Hospital System foreshadowed considerable changes needed in the delivery of care for ex-servicemen.[40] With declining patient numbers and the increased need to provide psychogeriatric care, the shift towards decentralisation and the integration of these services into existing regional and community facilities gained momentum.

By December 1991, 105 patients resided at Bundoora. The Department of Veterans’ Affairs mirrored the views of the earlier Brand report, and it identified that long-term psychiatric care for veterans could be more effectively served through the provision of mainstream psychiatric and nursing home services, rather than a dedicated single hospital. The Repatriation Commission and the Returned Services League of Australia agreed, and endorsed the move to specialised facilities in locations closer to patients’ homes and families.

With large operational costs and the decentralisation of psychiatric services, the closure of Bundoora and the replacement of services were announced. The remaining patients, many of whom had resided at the hospital for decades, were transferred to alternative accommodation. Senior Social Worker, Arnold Wheeler, commented that: ‘the day centre developed a very friendly club-like atmosphere over the years, and when it closed on April 1 [this year], it was a sad day for all fifty veterans and staff alike.’[41] After providing over 70 years of care to veterans, Bundoora Repatriation Hospital was formally decommissioned in October 1993.

In the redevelopment of the site, the Urban Land Authority planned to demolish all of the hospital infrastructure, including the homestead. Its appearance had suffered a steady decline since the Smith Family era. The interior was painted peach and aqua, the verandahs were enclosed, period features were missing, and an extensive concrete fire escape protruded from the second storey. Through the combined efforts of Darebin City Council, La Trobe University and the Preston Historical Society, Bundoora Homestead was heritage listed and saved from destruction. In 2001, Bundoora Homestead Art Centre opened as a cultural and heritage facility for the community, funded and managed by the City of Darebin.

Bundoora Repatriation Mental Hospital was established to provide long-term psychiatric care and rehabilitation for ex-servicemen with mental disorders officially recognised as resulting from war service. Due to its location, size and unique character, the homestead was identified as an ideal place for a convalescent farm. Over decades, the facility grew to accommodate hundreds of patients who suffered from the harrowing experience of war.

The analysis and interpretation of public records, alongside the compelling stories of Wilfred Collinson, ‘Lofty’ Cannon and Dr Cade, has enabled us to create a vivid account of Bundoora Homestead as a place that was dedicated to the shelter and psychological well-being of veterans. The outstanding discovery and application of lithium carbonate in the late 1930s by Dr Cade, which can now be further understood in relation to the harrowing circumstance of patients who though they had returned from war service, due to their diminished mental health, remained lost to their families. Delving into the homestead’s past, despite the initial trepidation for the sorrow that lay there, has proven to be a rewarding and enlightening experience. What has become truly evident, is a broader picture of the tragic ramifications of war.

Endnotes

[1] Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, 3 October – 7 December, 2014. Donna Mann who was the Exhibition Coordinator and Researcher for the exhibition Coming Home, contributed invaluable research to the preparation of this article.

[2] Further reading regarding PTSD can be found in Stephen Garton, The Cost of War: Australians Return, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1996, John Rafferty, Marks of War: War Neurosis and the Legacy of Kokoda, Lythrum Press, Adelaide, 2003.

[3] Marina Larsson, Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2009.

[4] Tanja Luckins, ‘”Crazed with Grief?” The Asylum and the Great War in Australia’, in Catharine Coleborne and Dolly Mackinnon (eds), Madness in Australia: Histories, Heritage and the Asylum, Queensland University Press, St Lucia, Qld, 2003.

[5] Iliya Bircanin and Alex Short, Glimpses of the Past: Mont Park, Larundel, Plenty, [Iliya Bircanin and Alex Short, Melbourne], 1995.

[6] Wallace, who was sired by the 1890 Melbourne Cup winner Carbine, was at stud at Bundoora Park from 1901 to 1917 and earned a fortune for the Smith family via successful progeny including the champion racehorse, Trafalgar. See Andrew Lemon, ‘Wallace of Bundoora: The Greatest Sire in Australia’, in Dr Jacqueline Healy (ed.), Bundoora Homestead: The Smith Family Era 1899–1920, Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, Fitzroy, 2007, pp. 29–37.

[7] NAA: A6006, 1920/4/13, Bundoora Stud Farm – Acquisition, Repatriation Department, Correspondence Files: Bundoora Convalescent Farm – Part 1 1920-1921, April 1920, p. 1.

[8] ibid.

[9] PROV, VPRS 7527/P1 Military Mental Hospital Correspondence Files, Unit 1, letter from the Deputy Commissioner, Repatriation Commission, Victorian Branch, to the Lunacy Department, Old Treasury Buildings, Melbourne, 8 November 1927.

[10] The Mental Treatment Act 1915, No 2600 [Repatriation], Victoria, 1915, available online at <http://www.ahpi.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/legislation-state.html>, accessed 19 April 2015.

[11] Argus, 20 May 1922, p. 20.

[12] ibid.

[13] Bircanin and Alex, Glimpses, p. 1.

[14] AWM: H19366. Bundoora Convalescent Farm, circa 1924, photographer unknown, silver gelatin print.

[15] PROV, VPRS 7453/P1 Trial Leave Registers, Military Mental Hospital Annual Examination Register, Unit 2.

[16] Dr David Cade, Department of Mental Hygiene, Hospitals for the Insane. Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane for the year ended 31 December 1925, Victoria, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, No. 11, 1927, p. 23.

[17] Dr David Cade, Department of Mental Hygiene, Hospitals for the Insane. Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane for the year ended 31 December 1933, Victoria, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, No. 6, 1935, p. 17.

[18] NAA: B3712, Drawer 174, Folder 10. ‘Bundoora Mental Hospital Padded Room in B Ward’, architectural plan 4, Commonwealth of Australia Department of the Interior, Works and Service Branch, Victoria, 5 July 1946.

[19] Now a residential building on the corner of Oakden Drive and Prospect Hill Drive, opposite the Bundoora Homestead Art Centre car park.

[20] Dr John Charles Catarinich, Department of Mental Hygiene, Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene for the Year ended 31 December 1938, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, No. 9, 1939, p. 17.

[21] Wallace Ironside, ‘Cade, John Frederick Joseph (1912–1980)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1993, available online at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cade-john-frederick-joseph-9657/text17037>, accessed 2 August 2015.

[22] Dr John FJ Cade, ‘Lithium Salts in the Treatment of Psychotic Excitement’, Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 2, No. 10, September 1949, pp. 349–351.

[23] ibid, p. 350.

[24] Patients were transferred for this procedure to the Repatriation General Hospital, Heidelberg.

[25] JF Cade, Lithium Salts’, p. 350.

[26] Dr John FJ Cade, Department of Mental Hygiene, Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene for the year ended 31 December 1949, Victoria, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, No. 1, 1951–52, p. 26.

[27] Rachel Buchanan, ‘Remembering A Forgotten Survivor’, Griffith Review, No. 18, Summer 2007–08, available online at <https://griffithreview.com/articles/remembering-a-forgotten-survivor/>, accessed 18 April 2015.

[28] A reference to Kanchanaburi, the POW base camp in Thailand, where allied troops including ‘Lofty’ Cannon and Searle were forced to work on the Thai–Burma Railway. Known as the ‘Death Railway’, it was a 415 km line between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma.

[29] Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, letter from Ronald Searle to Henry ‘Lofty’ Cannon, 30 August 1946.

[30] Buchanan, ‘Remembering A Forgotten Survivor’.

[31] Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, letter from Henry ‘Lofty’ Cannon to Ronald Searle, 28 January 1966.

[32] Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, letter from Henry ‘Lofty’ Cannon to Ronald Searle, 31 October 1966.

[33] City of Darebin Art and History Collection. Henry ‘Lofty’ Cannon, ‘So You Want “OUT”?’, Outlook, Bundoora, c.1968–1970, p. 22.

[34] Dr Thomas Retallick, Department of Mental Hygiene, Report of the Mental Hygiene Authority for the year ended 31 December 1960, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, No. 31, 1961–62, p. 44.

[35] Dr Harold Stone, Mental Health Authority, Report of the Mental Health Authority for the year ended 31 December 1968, Victoria, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, No. 35, 1969–70, p. 74.

[36] ibid.

[37] BJ Healey, ‘The Veterans’ Book Exchange’, The Homesteader (Bundoora Repatriation Hospital magazine), Bundoora, 1973, p. 5.

[38] ibid.

[39] BJ Healey, ‘Rehabilitation and Work Motivation for Long Term Psychiatric Patients’, Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1973, pp. 32–35.

[40] Ian Brand (Chairman), Review of the Repatriation Hospital System (Australia), Final Report, Melbourne, 1985.

[41] DVA News, Melbourne, November 1993, p. 4.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples