Last updated:

‘“She had always been a difficult case …”: Jill’s short, tragic life in Victoria’s institutions, 1952–1955’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Cate O’Neill.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article uses a range of sources in the public domain to tell the story of ‘Jill’, a state ward in Victoria whose experiences in institutions attracted an enormous amount of public attention between 1952 and 1955. Jill’s story became a vehicle for heated debates about the child welfare system, during a period of considerable tension and conflict that preceded significant reform in Victoria. The representations of Jill in the media, and the consequent public interest in her case, led to the creation of records that illuminate how ‘female delinquents’ were regarded, and dealt with, by authorities in the 1950s. Jill’s story demonstrates the difficult transition from a child welfare system that heavily relied on the church and charitable sector, towards a new system with more involvement and oversight from government departments, and the input of ‘professionals’ from the social work, psychology and criminology sectors. There have been many scandals and inquiries in the history of child welfare in Australia, however the ‘Jill’ story is unique in its focus on this young woman, rather than general policy issues or conditions within a particular institution. Ultimately, this tragic story demonstrates that the system in Victoria failed to help Jill, and the public interest in her plight was limited.

Introduction

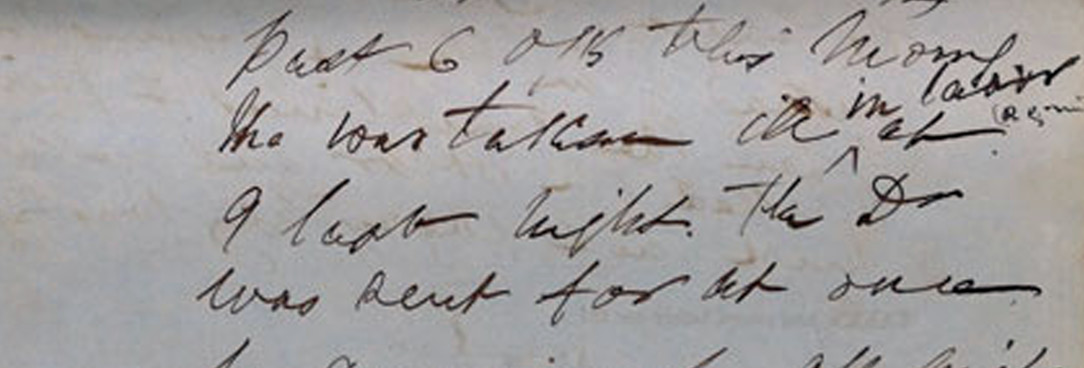

On 3 September 1955, a 16-year-old state ward broke into a staff room at Beechworth Mental Hospital and deliberately took an overdose of barbiturates. She died a few days later in Wangaratta Base Hospital. The coronial inquest into her death was held in December that year.[1] The young woman’s death, and the subsequent inquest, were prominently reported in Melbourne’s newspapers. Indeed, the experiences of this young woman in the ‘care’ of the State of Victoria attracted an extraordinary amount of public attention between 1952 and 1955. By the time of her tragic death in September, ‘Jill’ (the pseudonym used by journalists from 1955) was well-known to the Victorian public.[2]

The Victorian Government’s treatment of ‘delinquent girls’, particularly the inadequacy of the child welfare system to accommodate, let alone rehabilitate, them, was an issue that received media coverage from time to time in the 1950s.[3] In early September 1952, the issue became front-page news when it was revealed that a number of ‘uncontrollable and incorrigible girls’ aged 17 and under had spent brief terms at Pentridge Prison, a prison established for the detention of adults, in the preceding 18 months.[4] Responding to the public outcry, the Child Welfare Department (CWD) claimed that Pentridge ‘was the only place’ to send these girls.[5] The CWD made a statement: ‘We know this is scandalous, but there is no alternative. Such incorrigible girls have to be corrected and there is not a corrective institution for them in Victoria’.[6] One of these girls was Jill, then aged 13.

Over the next three years or so, Jill became something of a cause célèbre in Victoria. She was a vehicle for heated public debates about the state’s child welfare system, during a period of considerable tension and conflict that preceded significant reform. Between 1952 and 1955, Jill’s story was constructed and imagined by various people, for different purposes – to score political points, to sway public opinion, to push for reform, to sell newspapers. The many representations of Jill in archival records, newspaper articles and parliamentary debates illuminate aspects of Victoria’s treatment of ‘female delinquents’ that might otherwise have remained unrecorded, or at least, unknown to the broader public.

With the amount of attention currently being given to the issue of the abuse of children in institutions, abuse that is both ‘historic’ and much more recent, it can seem that the Australian public only recently became aware of the severe shortcomings of its child welfare system and the devastating impact it has had on so many people.[7] In fact, the history of institutional ‘care’ has been marked by regular inquiries (and media storms) dating back to the earliest days of government provision of child welfare. Periodically, public attention was directed at the conditions in children’s institutions, usually after allegations of abuse, mistreatment or mismanagement. A 2014 report by Shurlee Swain documents just how many inquiries there have been into children’s institutions in Australia.[8] Her report concludes that, despite the high number, these inquiries rarely resulted in any fundamental change; rather, they were about damage control.[9]

This article explores one such period of scrutiny in Victoria in the 1950s. The public attention, focused on Jill and her tragic experiences, has left behind records that shed light on systems and institutions that were ordinarily out of sight and out of the public consciousness.

From Royal Park Depot to Pentridge Prison

From the earliest days of the colony, the child welfare system in Victoria relied heavily on church and charitable organisations to deliver services for neglected children.[10] Another feature of the Victorian system was the lack of a strong, centralised children’s welfare department (unlike, for example, Queensland), or a representative body like the Children’s Councils that existed in South Australia and New South Wales and enabled communication between bureaucrats, policy makers and the philanthropic sector.[11] Nor was there much supervision or oversight of children’s institutions by Victorian government departments before the 1950s.[12] In fact, until 1956, the only institution for neglected children run by the state government was the Royal Park Depot, which had been established in 1880 as Victoria’s sole ‘clearing house’ for boys and girls. The idea was that children would stay briefly at the depot until they were boarded out, placed in an orphanage, sent out to service, or committed to a reformatory.[13] In actuality, many children ended up staying at Royal Park for long periods of time.

In 1922, the Medical Officer and Superintendent at Royal Park reported that the depot ‘has become a permanent or semi-permanent home for mentally and physically defective children … who are unfit for “boarding out” or “service”’.[14] Overcrowding was nearly always a problem at the Royal Park Depot, and at several times throughout its history the institution was pushed far beyond its capacity. For example, following the passage of the Infant Life Protection Actin 1909, the Secretary of the Department for Neglected Children and Reformatory Schools reported a large influx of infants at Royal Park, for whom adequate nursery facilities were not built until late 1913.[15] The depot also experienced severe overcrowding during the years of the Great Depression, with the collapse of the boarding-out system in Victoria.[16] ‘Criminal’ children also stayed at the depot when they were on remand from the courts.

Swain writes that Royal Park Depot was the focus of ‘a series of inconclusive inquiries into allegations of ill-treatment’ in the first half of the twentieth-century.[17] Claims of a ‘shocking state of affairs’ at Royal Park were aired in Melbourne newspapers in 1911, 1920 and 1922.[18] The severe overcrowding at Royal Park was a regular criticism, as well as the failure to segregate ‘normal, healthy children’ from other ‘types’.

In the early 1950s, more stories began to appear in the papers about conditions at the ‘crowded depot’, emphasising Royal Park’s lack of facilities for ‘delinquent girls’. At that time, apart from a section within Royal Park Depot, there was no government-run reformatory institution for girls in Victoria, and only a small number of denominational institutions for delinquent girls. Although a Government Reformatory for Girls (also known as the Protestant Girls’ Reformatory) existed from 1864 until 1893, the Victorian Government favoured juvenile correction for girls being ‘in private rather than official hands’. The Royal Commission into Reformatory and Industrial Schools in 1872 commended the work of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd with its inmates at the reformatory in Abbotsford (established in 1864) and recommended the establishment of a similar private institution for Protestant girls.[19] The 1887Juvenile Offenders Act allowed for the establishment of private reformatories, the first of which was the Brookside Private Reformatory for Protestant Girls, established in December 1887 near the town of Scarsdale.[20] As well as being privately-run, Brookside was favoured by the Department of Reformatory School for its rural location, allowing for the girls’ ‘absolute separation from disreputable friends and relatives’.[21] (The Department for Reformatory Schools also provided funding to denominational institutions for boys, such as the Salvation Army’s Bayswater Boys’ Homes (1897–1986) and the Morning Star Boys’ Home (1936–1975), run by the Franciscan Friars.)

Despite the existence of these private institutions, delinquent children were still required to spend periods of time at Royal Park, the state government’s ‘clearing house’. The accommodation of children on remand in close proximity with neglected children was a concern commonly raised about Royal Park.[22] An article in the Argus in 1951 described the conditions at Royal Park for delinquent girls:

Many of the delinquents are girls who had been distributed to other homes or placed in jobs from which they ran away. On return these ‘absconders’ are dressed in shapeless prison garb and denied most recreational facilities. The embittering effect of this treatment can be imagined, and the girls naturally spread their discontent to the others.[23]

At this time, the Victorian Government had very few options for institutional placement of ‘unruly girls’, particularly if they were not Catholic.[24] The CWD was dependent on the goodwill of those in charge of private institutions like Abbotsford Convent or the Elizabeth Fry Retreat in South Yarra.[25] When girls misbehaved or absconded, it was becoming common for these institutions to send them back to the care of the CWD, and the ‘blocked sink’ of Royal Park.[26]

In 1952, the discontent of delinquent girls at Royal Park became a highly prominent issue – it was at this time that the public first became aware of ‘Jill’. The papers reported that, following a series of escapes from Royal Park, and a ‘riot’ on 1 September, several girls had been sent to Pentridge Prison. Jill, ‘a barefooted, 13 year old girl’, was the second child in four days to be remanded to Pentridge, having been charged with criminal damage at the North Melbourne Children’s Court.[27] The scandal worsened when it became clear that this was not an isolated occurrence, and that a number of girls had been sent from Royal Park to Pentridge in the previous 18 months.[28] To make matters worse, a report had just been tabled in the Victorian Parliament, harshly criticising the state’s penal administration, singling out Pentridge’s female division, where the teenagers were incarcerated, as ‘hopelessly inadequate’.[29]

It is now clear that the detention or imprisonment of young women in adult prisons and mental institutions was not an uncommon occurrence at this time. The Australian Senate’s ‘Forgotten Australians’ report (2004) discussed the practice of detaining girls and young women in adult prisons and mental institutions.[30] In 1953, South Australian newspapers reported on the imprisonment in Adelaide Gaol of two ‘girl delinquents’, the ringleaders in an escape from Vaughan House Reformatory.[31] In New South Wales in October 1942, it was reported that 45 girls from the Parramatta Girls’ Training Home had been committed to Long Bay Gaol, following a series of riots and mass escapes (and criticism of the administration in the New South Wales Parliament and the press).[32] In 1944, Mary Tenison Woods, Chairman of the Delinquency Committee of the NSW Child Welfare Advisory Council denounced the practice of imprisoning girls, citing one case where a Parramatta girl with a mental age of eight was sentenced to Long Bay for 3 months, for ‘gross insubordination’.[33] From 1944, following the widespread concern over the number of children being sent to gaol, there was a period of significant reform in New South Wales. A new Director of Child Welfare, RH Hicks, was appointed in 1944, and the Child Welfare Department (of NSW) worked closely with its Advisory Council to implement changes including the recruitment of trained social workers, and a new approach to discipline and rehabilitation of juvenile offenders at institutions like Parramatta and Gosford Boys’ Home.[34]

In Queensland, it was common for ‘uncontrollable’ girls to be sent to adult mental institutions if the denominational institutions would not take them. The report of Queensland’s Forde Inquiry (1999) describes a system in the 1950s similar to Victoria’s, dependent on private institutions to accommodate delinquent girls:

The system worked satisfactorily (at least as far as the [Queensland] government was concerned) as long as the girls admitted to the homes were compliant enough not to cause a significant drain on resources. The situation was more complex for those girls who resisted institutionalisation and were labelled ‘uncontrollable’. None of the denominational homes were equipped to accommodate especially troublesome girls, and often they exercised their right to refuse to admit those they considered too difficult to handle or to discharge those who had become unmanageable after admission.[35]

Absconding and damaging institutional property were common reasons for female wards of the state to be placed in the reformatory section of Royal Park, or committed to prison. But the definition of female delinquent behaviour also had a moral element, with girls being punished for non-criminal acts like running away from home, being ‘uncontrollable’ or sexually active. Fielding writes that courts have tended to see the detention of young women, not as punishment, but as a necessary measure to protect the young woman from herself or from her environment.[36] The legislation in force at the time of these girls’ imprisonment at Pentridge in 1952, the Children’s Welfare Act 1933, contained definitions that applied specifically to girls of what constituted a ‘neglected child’. While boys and girls could be charged with ‘living under such conditions as indicate that the child is lapsing or likely to lapse into a career of vice or crime’ (this was abbreviated in ward files as ‘Likely to lapse’), the 1933 legislation also referred to two new categories: girls ‘found soliciting men for prostitution, or otherwise behaving in an indecent manner’, or ‘habitually wandering about a public place at night’.[37] These amendments resulted in an increasing number of girls becoming state wards from 1933. From 1954, girls in Victoria could also be charged with being ‘exposed to moral danger’,[38] described by Hamilton as a ‘nebulous term … a catch-all justification for incarcerating children engaged in any actual or potential sexual activity, and was applied almost exclusively to adolescent girls’.[39] By the 1980s, it was becoming clear that the vast majority of girls and young women in juvenile justice facilities were ‘status offenders’ who had not committed a crime; in fact, they were often victims or potential victims of crime.[40]

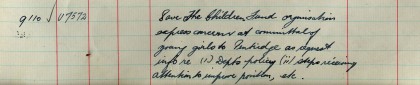

The different treatment of delinquent boys and girls was one of the issues raised in the public debates sparked by the news of Victoria’s ‘Pentridge girls’ in 1952. One member of the Labor Opposition remarked: ‘Boys break windows … and it is generally said that “Boys will be boys”. However, when a girl commits a misdemeanour, society wants to wreak vengeance upon her’.[41] On 3 September, another Labor politician facetiously blamed the Royal Park Depot for the predicament of the girls: ‘The institution is a disgrace, and people should not be housed there. It is no wonder the poor little kid smashed a window to get away. Probably, she did so because of the rats.’[42] Members of the public and various organisations (including Save the Children, the Howard League for Penal Reform, the Union of Australian Women, and the League of Women Voters in Victoria) made representations to the Chief Secretary of the Victorian Government, demanding to know what the government planned to do about the situation.[43]

Throughout September 1952, members of the Labor Opposition repeatedly took the opportunity to use the ‘Pentridge girls’ issue to score political points. On 9 September 1952, the Victorian Parliament debated a motion raised by the Opposition: ‘the administration of the Children’s Welfare Department which resulted in the incarceration of two children in gaol’.[44] During this debate, detailed information about the girls’ personal circumstances and case histories were aired, even though their cases were at the time sub judice. Premier McDonald blamed this breach of the girls’ privacy on the Opposition, for submitting its motion to discuss the issue, ‘with the object of making public, for political purposes, the unfortunate circumstances of these girls’. The Chief Secretary, Mr Dodgshun, justified his disclosure of confidential information as necessary for him to prove that the girls were ‘persistent absconders’, and thus legally incarcerated under section 19 of the Children’s Court Act.

Labor Opposition member for Carlton, William Barry, criticised the Chief Secretary for ‘bringing into Parliament the records of a number of little girls, although I know he can find nothing in them to be ashamed of. He could find nothing that would justify bringing a little girl into court, taking her boots off and standing her barefooted in the court room because, it was claimed, she would kick the life out of a policeman …’[45] Dodgshun said that he had ‘tried to refrain’ from revealing personal details of the girls in Parliament, but the Opposition had ‘forced the issue’. The Chief Secretary claimed that ‘incorrigible’ was a ‘mild expression to use’ when describing these girls. He stated that one girl currently in prison had come to the Royal Park Depot on a charge of ‘likely to lapse’ and the court had heard evidence of her sexual promiscuity, keeping late hours and other uncontrollable behaviour. Dodgshun said that ‘these girls and others of their ilk’ had been refused admittance into the denominational institutions in Victoria for ‘wayward girls’, and argued that, with no government-run reformatory for girls, there was nowhere else to put them but Pentridge.[46]

At times during this debate, it is unclear when the Chief Secretary was referring to actual cases of state wards, and when he was speaking more generally, ‘to illustrate the type of girl with whom the Department must deal’.[47] Rather than helping us to understand anything about the lives of these female state wards, the representations of the ‘Pentridge girls’, by politicians on both sides of the house, clearly illuminate how child welfare became a political football in Victoria in late 1952. The Labor Opposition members’ comments about ‘the little girls’ were designed to capitalise on the public outrage and land blows on a government already experiencing difficulties. The Victorian Government painted its own pictures of these girls in an attempt to justify the actions of the bureaucracy and the courts. Yet more representations of the ‘Pentridge girls’ appeared in Melbourne’s newspapers, as they became the focus of calls for reform in Victoria’s child welfare system.

Editorials condemned the girls’ detention, and expressed despair about the inadequacy of Victoria’s child welfare system. ‘Has anybody an old dungeon to let?’ asked the Argus on 12 September 1952. It called on the McDonald Government to act, now that ‘this scandalous business has been dragged into the daylight’. The Argus reported that it had received many letters demanding action – one group of citizens from the suburbs of Malvern and Toorak wrote to the paper urging it to launch an appeal to raise funds ‘for the building of an establishment which will provide such girls with proper guidance and training’ (they also enclosed cheques amounting to over 30 pounds).[48] One Melbourne grandmother was also moved by the press coverage to make a donation of five pounds to help the 13-year-old girl at Pentridge, via the Herald newspaper, which forwarded the money to the Chief Secretary.[49] Various commentators began to argue that the State of Victoria was a ‘neglectful parent’, and through its reliance on churches and charities, was shirking its responsibilities to vulnerable children.[50]

The shift towards a ‘professional’ system

The thinking around the care of children was shifting significantly in the middle of the twentieth century. This period saw the landmark ‘Care of Children Report’ in the United Kingdom in 1946, the growing influence of psychologists like Dr Edward John Mostyn Bowlby (pioneer of ‘attachment theory’), and an increasing emphasis on professional, specialised training for those working in child welfare.[51] By the early 1950s, this shift was beginning to be seen in the Victorian child welfare system. As Musgrove writes, ‘the clerks, philanthropists and religious personnel who had established welfare networks in the nineteenth century were replaced by professionals with increasingly specialised fields of training. The transition was not an easy one.’[52] In mid-1952, the Child Welfare Department’s first professionally trained social worker, Teresa Wardell, clashed with its Secretary (Mr EJ Pittard, who had been in the role since the late 1930s), when it became clear that Wardell’s approach to ‘therapeutic casework’ with the teenage girls at the Royal Park Depot ‘did not fit easily with the approach of existing staff’.[53] In October 1952, after several of these teenage girls had been sent to Pentridge, Wardell again protested to the Secretary about the conditions at Royal Park and the punitive treatment of delinquent girls, which she dismissed as belonging ‘to an era of at least half a century ago’.[54]

Calls for reform and criticism of Victoria’s social welfare institutions, focusing on the plight of the Pentridge girls, came from the emerging profession of social work, as well as from various ‘experts’ from the fields of psychology, sociology and criminology. Visiting Fulbright scholar, criminologist Professor Albert Morris of Boston University, weighed in on the debate in 1952. In his public lectures, Morris urged Victorians to listen to the social sciences and support their ‘constant research for truth’. It was time, he claimed, for an ‘earnest stocktaking of present methods’ in Victoria.[55] In October 1952, Morris argued that Victoria’s religious and charitable institutions were not equipped to handle ‘difficult kinds of cases’ like Jill’s: problem children needed ‘modern professional treatment’, and institutions needed ‘modern professional standards’.[56]

Dr Norval Morris from the recently-established Department of Criminology at Melbourne University was another expert prominently offering his advice to the authorities about the ‘Pentridge girls’. On 4 September 1952, Morris claimed that ‘a little bit of political courage’ would solve Victoria’s delinquent girl problem almost overnight. He urged the government to take over one of the ‘many big homes around Melbourne’ and establish a home where female state wards would have ‘a civilised chance of rehabilitating themselves’.[57] This advice was not welcomed by the Victorian Government, with one politician ridiculing Morris in parliament on 9 September: ‘Why does not the doctor accept the responsibility of taking action? Why does not this great genius, with all the solutions at his fingertips, have these girls at the university to determine whether the quiet, cultural, intellectual calm there under his benign, all-powerful influence, will not solve this situation?’[58]

Norval Morris’s claims that Victoria was ‘stingy’, particularly in contrast with New South Wales, got particularly good traction in the media.[59] At a meeting of the Victorian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children at the end of September 1952, Morris described the reforms that had taken place in New South Wales since 1944, pointing out that it had 28 institutions run by the state and 96 fully trained professional child welfare workers. A glowing account of the government-run ‘training schools’ for girls in NSW followed (these same institutions were the subject of the Royal Commission’s Case Study No 7, released in November 2014). An article by John Boland in October 1952 painted Victoria as being behind the times compared with New South Wales: while its system ‘may not be perfect’, he wrote, the gaoling of girls ‘went out years ago’.[60]

All of the major newspapers in Melbourne covered the ‘Pentridge girls’ story in late 1952. In September, the Herald ran a series of articles about the child welfare system in general (‘Victoria’s Unwanted Children’ by Lawrence Turner), adding to the growing sense of crisis. The media attention would seem to have led the Child Welfare Department to change its approach to dealing with female state wards who caused property damage. The Argus reported on 1 October that a 17-year-old who had broken a window at Royal Park was ‘saved from gaol’, when the CWD elected to pay a fine to the Children’s Court (a carpenter who was present at her hearing offered to repair the damage free of charge, theArgus reported).[61]

The politics of child welfare

Throughout September 1952, Victorian Labor politicians carved out their position on child welfare, firmly on the side of reform and modernisation. The Labor Opposition capitalised on the public dismay and got right behind the cause of the ‘Pentridge girls’, wasting no opportunities to score political points. William Barry, the member for Carlton, and Bill Galvin, Deputy Leader of the Opposition, were particularly prominent – leading a delegation of 14 Labor politicians to Pentridge to inspect the conditions under which the teenagers were held, attending hearings at the Children’s Court and regularly commenting on the case in the papers.[62] When the girls were released, Mr Barry took credit, claiming to the press, ‘That’s how to get things done. It’s more than the government would do.’[63]

This advocacy by Labor politicians took place during a time of considerable disarray in Victorian politics. Their support for the girls was one of several manoeuvres designed to destabilise and attack the Country Party government. On the same September day that the girls were released from Pentridge (with four Labor members in attendance at the Children’s Court, two of them taking part in the legal proceedings), Premier McDonald barely survived a no-confidence motion in the Victorian Parliament. Next month, he was forced to resign as Premier after Labor supported Thomas Hollway to block supply, and Hollway became the ’70 hour Premier’. On 31 October, the Governor of Victoria ordered Hollway to resign and reinstated McDonald as Premier, calling an election for 6 December 1952, which saw the election of the Cain Labor government (the first majority Labor government in Victoria’s history).

In January 1953, the new Chief Secretary, Bill Galvin, stated that he would soon report to Cabinet on his plans to reform child welfare in Victoria, and again appealed to interstate rivalry to help get his point across (‘NSW leads us on child care’ proclaimed the Argus on 21 January).[64] In April 1953, Galvin flagged ‘a great increase in scope of child welfare work done by the State and comparable improvements in its methods’.[65]

Unfortunately, the changing political climate did not improve the situation for Jill. In July 1953, she was back in the papers, after another escape from Royal Park Depot.[66] Then, on 3 August, the Argus reported that Jill was again in Pentridge Prison – it was her third time there. She had been involved in ‘another wild scene’ at Royal Park, and was charged with having caused malicious damage estimated at 30 pounds.[67]

William Barry, the prominent critic of the government during the previous year’s ‘Pentridge girls’ storm, was now the Health Minister. In a statement, Barry said he still had faith in Jill, and he refused to believe that nothing could be done to rehabilitate her.[68] In line with the Cain government’s child welfare reform agenda, Barry told the Argus of his intention that Dr Cunningham Dax, Chairman of the Mental Hygiene Authority, would examine and report on Jill. Dax was another expert who had gotten involved in public debates in September 1952, stating that what Victoria needed was an institution where persons could be committed from the courts for psychiatric treatment.[69] Mental health was another area undergoing change and reform in the early 1950s – the establishment of the Mental Hygiene Authority in February 1952, and the recruitment of Dr Dax to Victoria, demonstrated the growing emphasis on mental illness prevention, and the view of ‘mental hygiene’ as ‘intimately concerned’ with the provision of social services.[70]

At this time, juvenile delinquency increasingly began to be seen as an issue, not just for the CWD, but also for the Mental Hygiene Authority (MHA). From 1952, the MHA’s Children’s Court Clinic began to see more state wards, referred from the CWD. In 1953, the clinic reported that it had examined 25% more children than the year before (and that four of these children came from Pentridge Prison).[71] By 1954, the clinic reported that the demands from the CWD for its services to state wards were greater than could be met. The annual report of the MHA urged the appointment of at least one more psychologist, so that it could continue to help disturbed children as ‘an insurance against future maladjustment’.[72]

The Chief Secretary’s records at PROV show that Dr Dax examined Jill at Pentridge in August 1953. They also show that members of the public again took a great interest in Jill’s plight, some even contacting the Chief Secretary and offering to adopt her.[73] On 16 September, the Children’s Court ordered that Jill be released from Pentridge and returned to Royal Park. She escaped from the depot that same day, was captured by police in Footscray and sent back to prison – once again ‘the Pentridge girl’ was in the papers.

In parliament on 16 September 1953, Keith Dodgshun, the former Chief Secretary, asked what the Labor government intended to do about Jill this time. He made the point that ‘it is extremely easy for members, in Opposition … to criticise the actions of the Administration … the Chief Secretary is now confronted with the same problem as that which faced the Government of which I was a member with regard to keeping a minor at Pentridge’.[74] Other members of the Opposition seemed to enjoy reminding the new Chief Secretary, Mr Galvin, of his stance during the ‘Pentridge girls’ crisis of 1952 and his lack of options this time around. Country Party member for Benambra, Thomas Mitchell, taunted the Chief Secretary about ‘his “hell” girl’ during a debate about an unrelated matter: ‘she was a thoroughly bad lot, and you promised to let her out. You betrayed her …’[75]

The media stories about Jill continued, and the news got even worse. While Jill was in Pentridge in September 1953, the Sun News-Pictorial published a series of articles (under the title ‘Cheating Children’) criticising Victoria’s child welfare institutions. On 22 September, Mr Galvin denied allegations (made by released female prisoners) that Jill was being kept manacled in a darkened cell at Pentridge. The same article reported that she had been admitted to Royal Melbourne Hospital on Sunday 20 September ‘unconscious with head injuries’.[76] When news of Jill’s hospitalisation became public, Mr Galvin was forced to admit that Jill was injured after having jumped from the roof of a 25 foot-high building at Pentridge.[77] On 22 September, the Age reported that Mr Galvin was willing to allow ‘any responsible person’ to take care of the girl, who had since been returned to Pentridge from the hospital.[78] As the Argus editorial made clear on 24 September, despite the change of government and the talk of reform, Victoria’s penal, child welfare and mental hygiene systems were still not able to cope with cases like Jill’s.[79] (In October 1953, it was reported that Jill had been placed in a private home with ‘good Christian people’.)[80]

The government attempted to recover from this spate of bad publicity by announcing its plans for sweeping reforms to child welfare in Victoria. Part of the ‘new deal’ was the appointment of a new secretary of the Children’s Welfare Department in November 1953 (Mr JV Nelson, replacing EJ Pittard) and the drafting of new child welfare legislation.[81]

‘Why have I been forsaken?’

On 1 December 1954, the day when Victoria’s new Children’s Welfare Actreceived Royal Assent, the Argus was reporting on the inquiry by the federal executive of the Australian Labor Party into its Victorian branch, which would culminate in the Labor Split of 1955.[82] The internal conflict within Labor provides some explanation for the slow progress in child welfare reform during 1954 and 1955 under the government of John Cain. In the course of this unrest, Mr Barry was expelled from the party in April 1955, and was replaced as Health Minister by ‘Val’ Doube.[83]

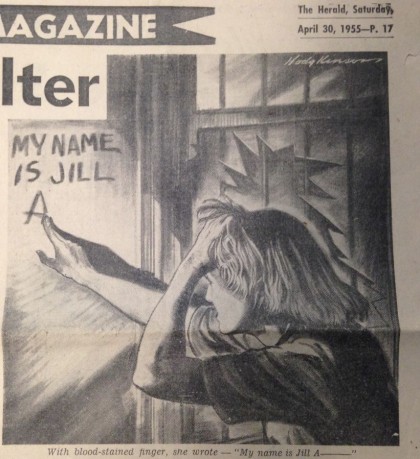

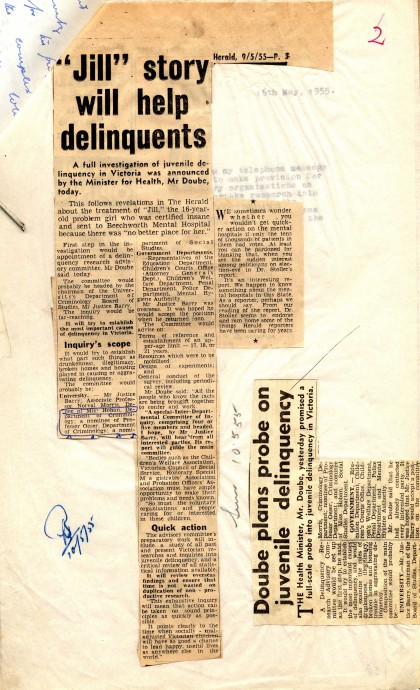

It was in April 1955 that the ‘Jill’ pseudonym was first used to refer to the young woman whose story was already so familiar to the Victorian public. She was named Jill by Osmar White, in his article in the Herald Week-end Magazine on 30 April. White would have been well-known to readers for his dispatches during World War II from Papua New Guinea and later, from the final days of the war in Germany.[84] White’s article revealed to the public the latest sensational episode in Jill’s story – on 23 April 1955, she had been certified insane and admitted to Beechworth Mental Hospital.[85]

White’s double-page article (headlined ‘To find this girl shelter State brands her INSANE’,) was illustrated with an artist’s impression of Jill in a cell, and photographs of Messrs Galvin, Barry and Doube with the caption ‘…And these men know the truth.’ In this article, White presented a detailed account of Jill’s ‘cruel case-history’ as a state ward. It included the opinions of various anonymous ‘experts’ to argue that Jill was not insane – rather, White asserted that:

Jill has been put in a mental hospital because she has been a hopeless nuisance to the Children’s Welfare Department, the police, the Penal Department and the Mental Hygiene Authority.

And isn’t it true that she has been a hopeless nuisance simply because this State has failed to provide proper care of its orphans or neglected children – because we haven’t provided proper homes and clinics for children who have, through no fault of their own, become social misfits? Where do we go from here?[86]

This first Jill article by Osmar White shares features with the sensationalist journalism about juvenile delinquency that was popular in the early 1950s – shock-value headlines, pulpy illustrations and dramatic language (‘Then came the blow that destroyed her world. Jill’s grandmother fell ill and was sent to hospital … They were remanded to Pentridge – with the prostitutes, thieves and murderesses in that deplorable, stinking Women’s Block …’). These popular representations of delinquency were designed to titillate and generate ‘moral panic’ in equal measure.[87] White’s article about Jill capitalised on the public’s hunger for these stories, which can be seen as part of the ‘well established discourse about delinquency’ that existed in Victoria in the 1950s. This discourse, according to Bessant, comprised the sensationalist images and accounts in the press, together with the scientific explanations of delinquency from a network of educationists, researchers, social workers and psychologists.[88]

White was clearly in close contact with a number of these professionals – the article quotes various anonymous insiders, criticising the CWD’s treatment of Jill, and the assessment of her mental health. The article begins: ‘We will call her Jill. That is not her real name. Her real name should never, in common decency, be divulged’. Despite White’s claim to the moral high ground, it is clear that the detailed case history he presents in this article was provided to him by at least one of these professionals in a violation of trust and privacy. In another ‘Jill’ article published in May 1955, White reveals that he had indeed seen Jill’s case files – one could speculate that his source was perhaps the ‘qualified social worker who has done everything possible to prevent the girl’s certification’ referred to in the 30 April piece. White’s articles were produced in collaboration with professionals who were desperately advocating on behalf of Jill, at the same time as they were campaigning for broader change within a system that still did not pay sufficient attention to their expert views.

When White’s article was published in April 1955, a state election was looming and the Cain government was in crisis. The article was certainly successful in mobilising public support – the Herald was flooded with letters from readers, including numerous offers from members of the public to take Jill into their homes.[89] Other letter-writers criticised the government: ‘Perhaps if we had not committed ourselves to the [Melbourne 1956] Olympic Games we would have money, men and materials to help with such cases as Jill’s’, wrote the Balwyn Women’s Club. Leaders of Church organisations in Victoria called for immediate action to help the state’s ‘forgotten children’.[90] Norval Morris warned that ‘unless the State spends more money on the reformatory side of child welfare, another series of “Jill” articles will have to be written five years’ hence’.[91] The Herald published numerous ‘Jill’ articles throughout May 1955, and got behind White’s call for an independent review of Jill’s case, offering to bear any associated expenses.[92]

The Herald’s coverage of this issue also included increasingly defensive statements from the Health Minister, Val Doube, and Chief Secretary Bill Galvin. The ministers’ initial response to the sensational Jill article said while it was ‘useful’ that the public learned of social tragedies like Jill’s, White’s article unjustifiably hurt the feelings of patients in Victoria’s mental hospitals, not to mention the feelings of ‘children and adults who have made a success of life through the efforts of the Children’s Welfare Department’. The politicians urged Victorians to see ‘the problem of the Jills’ from the perspective of the authorities, and imagine what Jill’s care and welfare had meant in man-hours and money. ‘In this one case, about 250 pages of letters and reports have been written from the CWD, all for the patient’s benefit and welfare’.[93]

Osmar White responded angrily in the Herald on 4 May, saying that the ministers had ‘shockingly smeared’ Jill with their talk of sexual promiscuity, thieving and drugs and alcohol. White wrote, ‘They have introduced the history of other “Jills” into their illustration of the difficulties they face, to try to cloud the issue about THE Jill I wrote about’.[94] Galvin countered that he was not smearing Jill, but ‘referring to the “Jills of the State” … We said we had several “Jills” to deal with.’[95] Indeed there are several Jills that emerge in the newspaper articles: different Jills were constructed for different purposes. In these public representations, there is constant tension about whose account is the story of the ‘real Jill’.

The denunciation of the government continued – Mr Barry, now a free agent, added his voice to the widespread criticism of his former colleagues.[96] On 17 May 1955, a joint statement from Mr Doube and Dr Dax announced that Jill’s certification had been annulled. They reported that she had ‘settled down’ at Beechworth and because of the improvement in her condition, Jill was now a ‘voluntary boarder’.[97] The Herald and its readers were not reassured by the announcement that Jill was no longer ‘insane’. On 18 May, the Herald editorial urged the state not to ‘close its file on “Jill”’:

‘Jill’s’ drift from unsuitable foster homes to the Royal Park depot, to gaol, and then to a mental hospital points to a scandalously wide gap in the social therapy side of the CWD … For the sake of other children, our makeshift services must be quickly overhauled. Teams of qualified social workers and Children’s Court clinics are an urgent part of the need. The story of ‘Jill’ is the strongest argument for action.[98]

Sadly, from this point in the story, Jill’s file would continue to expand. It was soon revealed that five days after her certificate was annulled, Jill had attacked three nurses at Beechworth Mental Hospital in a ‘sudden outburst of aggression’. Jill had also taken tablets, barricaded herself in a dorm, smashed glass and smeared blood on the walls. Dr Herbert Bower, the superintendent at Beechworth, decided to ‘ignore the episode’ and proceed with Jill’s ‘social therapy’, inviting her to stay at his home that night. However, Dr Dax soon ordered her removal to the Royal Melbourne Hospital, when fragments of glass showed up in Jill’s stomach.[99]

In early June, the Herald reported that Jill was ‘out of danger’, her ‘physical condition … not causing anxiety’. It stated: ‘Interest in the Jill case is now focused on the reactions of the new State Government’, Labor having lost government to Henry Bolte’s conservatives at the end of May 1955.[100] In July, Norval Morris challenged the new government to commit adequate funding to the child welfare system, describing the new Children’s Welfare Actas ‘promising’, but warning that ‘its promise will only be fulfilled if the public and politicians … are prepared to pay for it’.[101]

It would seem that the Bolte government continued down the same path with Jill, who was recertified in late June and again committed to Beechworth.[102] Then, in September 1955, Osmar White announced in the Herald that ‘the story of “Jill” is finished’.[103] Jill’s death following her deliberate overdose was front page news in the Argus on 10 September.[104] These articles revealed her real name, and more details of her tragic life, to the public. White wrote:

No one could have prevented the tragedy of her birth.

But I believe – and experts know – that the tragedy of her death could most probably have been prevented if the State of Victoria had done its duty …

Remember ‘Jill’, the bright-haired little girl, whom nobody could save, because nobody cared about her soon enough to save her …

Remember ‘Jill’, people of Victoria, and be too ashamed ever to let it happen again.[105]

The final instalments in Jill’s story were published at the time of the inquest in December 1955. The inquest deposition files at PROV contain one page of testimony from social worker Marjorie McDonald, who said she first met Jill at the Children’s Court in Melbourne in 1952. The official inquest records do not contain details of further evidence McDonald gave at the inquest, apparently from the public gallery. According to the Argus on 6 December:

A slim young woman in a grey costume provided a sensation in the last minutes of an inquest here today … After nearly five hours, when the Court had heard 11 witnesses, Mr JC Bell, SM leaned forward and formally asked: ‘Is there anyone else present who can give evidence to this inquest?’ From the public gallery, Marjorie McDonald, social worker employed by the Mental Hygiene Authority, stepped forward to state views she had travelled 145 miles by car to give.[106]

She stated that after Jill was admitted to Beechworth Mental Hospital, McDonald had tried to continue their relationship, but that Dr Bower had refused her access. ‘Three weeks before Jill died, I received a letter she had smuggled out of Beechworth. She asked had I forgotten her, why I had not kept in touch. It was obvious Jill never received parcels and letters that we sent her.’

In the Argus, McDonald claimed that ‘Jill need not have died. She was used as a guinea pig for mental hygiene in Victoria’.[107] On 12 December, the Agereported that McDonald had resigned from her position at the Mental Hygiene Authority to be free to reveal ‘circumstances’ about Jill’s treatment and death.[108] The social worker Teresa Wardell, who had also known Jill at Royal Park Depot, wrote a letter which was published in at least two Melbourne newspapers just before Christmas in 1955. Wardell wrote:

I feel compelled to write in defence of … ‘Jill’, who was persistently represented to the public by Government departments as a problem child, for whom everything was done that could have been done.

That is very far from the truth.

The final ignominy and cruelty to which she was subjected has shocked us all, and no assurances from the Minister for Health will make any difference.

The Children’s Welfare Department must take full responsibility for the tragic life of [Jill] as a ward of the State.[109]

As well as defending the ‘real Jill’ against false representations, Wardell’s letter to the Herald complained about the treatment she had received while employed by the CWD in 1952: ‘I was there as a social worker whose job it was to study and make recommendations for the future care of adolescent girls. I was given no authority in spite of my long experience in the field of child welfare, and I was refused all opportunities to carry out a proper programme of care and rehabilitation.’[110]

By the end of 1955, the Bolte Government had begun to implement the long-awaited reform of Victoria’s child welfare system. On 1 September, Chief Secretary Arthur Rylah announced the appointment of a new Child Welfare Advisory Council for Victoria, a key provision of the 1954 Children’s Welfare Act. Some of the council’s earliest work was to abolish the ‘bread and water’ punishment for children in institutions, and to recommend the establishment of a training scheme for staff in orphanages and other children’s institutions.[111]

Child welfare continued to be a source of political conflict in Victoria. In December 1955, former Health Minister Mr Doube criticised the provisions in the new legislation that allowed ‘temporary isolation up to 24 hours’ as punishment for children in institutions.[112] Jill’s case was again discussed in the parliament, during a debate about the Bolte Government’s approach to juvenile delinquency. The Member for Camberwell Robert Whateley reflected:

Over the years of that girl’s life, people who were paid to deal with her made a hopeless mess of it. She reached the stage where the whole world seemed to be against her. She became so much of a rebel that she died … That was a life thrown away. It does not matter which Government was in power at the time. The main thing is to ensure that the people obtain some insight into these matters.[113]

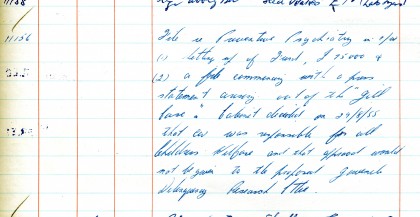

The Labor Opposition chastised the Victorian Government for not putting into action the plans of the previous administration to address juvenile delinquency. Mr Doube claimed that Premier Bolte was acting out of ‘sheer political spite’ in his refusal to support the proposed research committee into juvenile delinquency.[114] An entry in the Index to the Chief Secretary’s Correspondence at PROV suggests that a Cabinet decision in August 1955 not to fund this committee was indeed connected to the ‘Jill case’.[115]

Although the Bolte Government failed to establish a research committee, it did set up a Juvenile Delinquency Advisory Committee, which reported in 1956. The Barry Report (named after the Committee Chairman John Vincent Barry) validated many of the criticisms made during the ‘Pentridge girls’ and ‘Jill’ crises. The report stated that Victoria’s institutions needed additional help from psychiatrists, psychologists and trained social workers.[116] On the topic of ‘so-called Reformatory Schools’, the committee called for the state government to have full administrative control of these institutions. Furthermore, the committee declared, ‘We consider that it is not desirable that persons under seventeen should be committed to institutions under the control of the Penal Department’.[117]

The Barry Report also drew attention to the urgent need for Victoria to provide suitable accommodation for ‘children and juveniles suffering from grave mental disorders … so that it may be possible to avoid sending emotionally mal-adjusted, delinquent young persons to security sections of mental hospitals where, at present, they may be accommodated with chronic, disturbed, adult mental patients’.[118] The committee called for the expansion of the Children’s Courts Clinic and recommended that juveniles undergo ‘proper pre-sentence diagnostic appraisal’. The Barry Report resulted in the passage of a newChildren’s Court Act in 1956 which made significant changes to sentencing procedures including the abolition of whipping.[119] In another suggestion of the influence Jill’s story had on policy development in Victoria in the 1950s, the files at PROV relating to the Juvenile Delinquency Advisory Committee’s work contain numerous press clippings relating to her case.[120]

On 31 December 1955, on the eve of a new year, the Argus carried an optimistic, if cautionary, piece by Melbourne University Professor of Psychology Oscar Oeser. He reflected that the new Children’s Welfare Act, while ‘not the best that could be passed’ was ‘better than the previous jumble of acts’. Oeser predicted that this legislation would begin to have an effect on children and on public opinion in 1956. His article concluded: ‘I believe that in 1956 Victoria’s repute in the vast field of education and social science generally will grow … IF WE DON’T CHEESEPARE AND DON’T STAND STILL DURING THAT YEAR AND THE NEXT 10 YEARS’.[121]

Reflecting on Jill, sixty years later …

Sixty years later in Victoria, much has changed, but the inquiries continue, as do the media reports, the public concern and the claims that governments are not sufficiently resourcing the child protection system.[122] At the time of writing this article, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse is preparing to come to Victoria for hearings into the management of the government-run youth training and reception centres that were established after the passage of the Children’s Welfare Act 1954, including Winlaton (1956 to 1991), the government-run institution for girls. In 1955, when Osmar White’s articles about Jill were causing a political storm, the Chief Secretary Mr Galvin said, ‘I know the deficiencies of the Department. That is precisely why we have started on a new place, Winlaton at Nunawading’.[123] Testimony from former inmates of Winlaton about their demeaning and degrading experiences in ‘care’ are a stark demonstration that the changes introduced in Victoria from 1955 failed to address many of the systemic issues in the child welfare system.[124] This story about how the system let down one vulnerable child and failed in its duty of care is but one of many in the history of Australia’s children institutions. The story is unusual in the amount of interest focused on one person, over a number of years. Ultimately though, the attention given to Jill’s plight was short-lived and her story had little impact on the system.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 1810, Item 1955/1616 (name on file withheld to protect privacy). The quote in the main title of this article is from Victorian Health Minister Mr Cameron, commenting on the inquest into Jill’s death. ‘Beechworth chief “tried all he knew to save Jill from herself”’, Argus, 16 December 1955, p. 6, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/71786822> accessed 1 September 2015. Special thanks to Dr Natasha Story for her research assistance in 2012 and 2013 which was tremendously helpful to me in writing this article.

[2] Throughout this article, out of respect for the privacy of this young woman and her family, I have chosen to use the Jill pseudonym. To write this article, I have only drawn on sources that are available in the public domain. Presumably, there are many more records about Jill within PROV’s collection and the records at the Department of Human Services Archives, records which are closed to the public under section 9 of the Public Records Act 1973. During my research, I obtained access to a case file relating to Jill that is part of the Teresa Wardell Collection at the University of Melbourne Archives. In this article I have not disclosed any information from this file that was not already in the public domain.

[3] See for example Pamela Ruskin, ‘State’s neglected children: danger abounds in crowded depot’, Argus, 8 February 1951, p. 2, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/23036282>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[4] ‘Gaol had other girls too’, Argus, 4 September 1952, p. 1, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/23213196>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ‘Girl, 13, now in Vic. Gaol’, News (Adelaide), 6 September 1952, p. 10, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/130863929>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[7] See chapter 5, ‘Why abuse occurred and was able to continue’ in the Australian Senate’s Community Affairs References Committee, Forgotten Australians: a report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children, Commonwealth Government, Canberra, 2004, available online at <http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/report/index>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[8] See appendix 1: Australian inquiries into institutions accommodating those under the age of 18, 1852–2013, Shurlee Swain, History of Australian inquiries reviewing institutions providing care for children, Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Sydney, 2014, available at: <http://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/documents/published-research/historical-perspectives-report-3-history-of-inquir.pdf>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[9] Ibid., p. 7.

[10] The earliest organisations providing help to ‘orphans’ in Victoria were the Dorcas Society and the St James’ Visiting Society, which led to the establishment of the Melbourne Orphan Asylum in 1853. See Rosemary Francis, ‘Melbourne Orphan Asylum’, The Australian Women’s Register, 2003, available at <http://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/AWE0611b.htm>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[11] Swain, ‘History of Australian inquiries’, p. 5.

[12] This fact was acknowledged in the ‘Submission by the Government of Victoria to the Senate Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care’, submission no. 173, July 2003, p. 5, available at <http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[13] Cate O’Neill, ‘Royal Park Depot (c.1880 – 1955)’, Find & Connect web resource, available at <http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/vic/biogs/E000118b.htm>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[14] Department for Neglected Children and Reformatory Schools, Report of the Secretary and Inspector for the year 1922, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1922, p. 4.

[15] Department for Neglected Children and Reformatory Schools, Report of the Secretary and Inspector for the year 1910, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1910, p. 4.

[16] O’Neill, ‘Royal Park Depot’.

[17] Swain, ‘History of Australian inquiries’, p. 8.

[18] See for example: ‘Royal Park Depot. Treatment of State Wards. Very Unsatisfactory Position’, Argus, 20 October 1911, p. 7, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11625448>, accessed 1 September 2015; ‘Neglected Children’s Home. Filth, Vermin and Disease. Appalling Death Rate’,Argus, 26 March 1920, p. 6, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1685944>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[19] George Guillaume and Edward C Connor, The Development and Working of the Reformatory and Preventive Systems in the Colony of Victoria, Australia, 1864–1890, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1891, pp. 22–23, available at <http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/243591>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[20] Cate O’Neill, ‘Brookside Private Reformatory for Girls (1887–c.1900)’, Find & Connect web resource, available at <http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/vic/biogs/E000316b.htm>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[21] Guillaume & Connor, The Development and Working of the Reformatory, p. 23.

[22] ‘Delinquent Boys. Evils of Remand Depot. Lack of Accommodation.’,Argus, 18 August 1928, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/3951026>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[23] Ruskin, ‘State’s neglected children’, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23036282>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[24] In August 1940, the CWD had ceased funding two private reformatories (Riddells Creek Girls’ Home, run by the Salvation Army and the Roman Catholic Reformatory at the Convent of the Good Shepherd in Oakleigh). Children’s Welfare Department and Department for Reformatory Schools,Report of the Secretary for the years 1939 to 1943, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1944, p. 7.

[25] The Chief Secretary, Mr Dodgshun, pointed out that the system in 1952 was dependent on the goodwill of those in charge of these denominational institutions. Victoria Parliamentary Debates (VPD), Session 1951–52, Vol. 239, 9 September 1952, p. 1805. Digitised copies of Hansard are available for download at <http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/hansard/>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[26] ‘State “stingy to children”’, Argus, 1 October 1952, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23207814>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[27] See ‘Girl, 13, now in Vic. Gaol’.

[28] See ‘Gaol had other girls too’.

[29] Report of the Inspector-General of Penal Establishments on Developments in Penal Science in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States of America; together with Recommendations relating to Victorian Penal Administration, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1951–1952, p. 96.

[30] Forgotten Australians, p. 120.

[31] ‘Two Reformatory Escapees in Gaol’, Mail (Adelaide), 19 December 1953, p. 3, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/58874390>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[32] ‘Grave charges against Minister’, Daily Examiner (Grafton), 14 October 1942, p. 2, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/194061854>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[33] ‘State and the Child’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 February 1944, p. 4, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17872003>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[34] ‘Child welfare changes’, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 July 1944, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17913566>, accessed 1 September 2015; ‘The new approach to child welfare’, Advertiser, 1 October 1948, p. 7, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article43785301>, accessed 1 September 2015

[35] Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions, Department of Families, Youth and Community Care, Brisbane, 1999, p. 142.

[36] June Fielding, ‘Female delinquency’, in Paul R Wilson (ed.), Delinquency in Australia: a critical appraisal, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1977, pp. 153 and 172.

[37] See section 2 (b) of the Children’s Welfare Act 1933 (Vic.), available at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/cwa1933167/>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[38] See part 3, section 16 (j) of the Children’s Welfare Act 1954 (Vic.), available at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/cwa1954167.pdf>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[39] Madeleine Hamilton, ‘A process of survival’, Overland, No. 215, Winter 2014, available at <https://overland.org.au/previous-issues/issue-215/feature-madeleine-hamilton/>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[40] See Forgotten Australians, p. 66; ‘Submission by the Government of Victoria’, 2003, p. 10; Christine Alder, ‘Theories of Female Delinquency’, in Allan Borowski and I O’Connor (eds), Juvenile crime, justice and corrections, Addison Wesley Longman , South Melbourne, 1997; Kerry Carrington, Offending girls: sex, youth and justice, Allen & Unwin, St Leonard’s, NSW, 1993, pp. 16–17.

[41] VPD, 9 September 1952, p. 1801.

[42] VPD, 3 September 1952, p. 1701.

[43] There are a number of entries in the registers to the Chief Secretary’s correspondence relating to public concern about the ‘Pentridge girls’. See for example PROV, VPRS 3994/P0 Register of Inward Correspondence, Unit 139, Items 7961 and 9110, and Unit 140, Items 7358, U7572 and 7689. Unfortunately, the corresponding files are not in VPRS 3992/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence III, which contains minimal records from the period 1952 to 1955. The Chief Secretary’s Department was a key element of the Victorian public service until 1979. The Chief Secretary was the position with ultimate responsibility for neglected children and juvenile offenders until 1970, when the Social Welfare Department assumed full responsibility for child and family welfare in Victoria. The Chief Secretary’s administrative involvement in child welfare in Victoria means that the records of this department can be a rich source of information about children and families’ interactions with the child welfare system.

[44] VPD, 9 September 1952, pp. 1799–1820.

[45] Ibid., p. 1816.

[46] Ibid., p. 1805.

[47] Ibid., pp. 1809–1810.

[48] ‘Has anybody an old dungeon to let?’, Argus, 12 September 1953, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23203458>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[49] PROV, VPRS 3994/P0, Unit 139, 22 September 1952, register entry 7961.

[50] Pamela Ruskin wrote in the Argus in 1951: ‘It is not the children who should be charged as neglected, but the rest of the population as being neglectful!’, see ‘State’s neglected children’; in October 1952, criminologist Norval Morris, also writing in the Argus, declared, ‘If Victoria could be prosecuted for being a neglectful parent, it would be found guilty’, see ‘State “stingy to children”’.

[51] Cate O’Neill, ‘Care of Children Committee (1946)’, Find & Connect web resource, available at <http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/vic/biogs/E000347b.htm>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[52] Nell Musgrove, ‘Teresa Wardell: Gender, Catholicism and Social Welfare in Melbourne’, in Founders, Firsts and Feminists, eScholarship Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 2011, p. 130.

[53] Musgrove argues that perceptions of social work as a ‘feminised field’ hampered its acceptance as a ‘profession’, ibid., p. 138. Former social worker in the Children’s Welfare Department, Donna Jaggs, offers another perspective of the gender aspects of the CWD’s reluctance to recognise the authority of social workers like Teresa Wardell. In an oral history interview, Jaggs recalled that the CWD was ‘mainly manned, quite literally, by men in the administrative division of the public service’. Donella Jaggs interviewed by Jill Barnard in the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants oral history project, available online at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn5079534>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[54] Musgrove, ‘Teresa Wardell’, p. 139. Correspondence between Wardell and the Child Welfare Department from 1952, as well as a case file relating to ‘Jill’ (on restricted access) is in the Teresa Wardell Collection, accession number 1981.0123, University of Melbourne Archives.

[55] ‘Delinquency Control. Must Recognise Shortcomings’, Age, 5 August 1952. All articles from the Age cited in this article were accessed from the Google News Archive, available at <https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=MDQ-9Oe3GGUC>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[56] ‘Reforming Victoria’s Penal System’, 31 October 1952, transcript of speech by Albert Morris in Series 7/10, ‘Howard League for Penal Reform [1955]’, Teresa Wardell Collection, University of Melbourne Archives.

[57] ‘Pentridge isn’t only place, expert says’, Argus, 4 September 1952, p. 14, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/23211817>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[58] VPD, 9 September 1952, p. 1814.

[59] See ‘State “stingy to children”’.

[60] John Boland, ‘They don’t gaol girls in NSW’, Argus, 7 October 1952, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23202185>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[61] ‘Girl saved from gaol’, Argus, 1 October 1952, p. 3, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23207720>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[62] ‘Labor MPs visit prison’, News (Adelaide), 15 September 1952, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article130864464>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[63] ‘Girls moved from gaol’, Argus, 17 September 1952, p. 1, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23216694>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[64] ‘NSW leads us on child care’, Argus, 21 January 1953, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23223306>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[65] ‘Our obligation’, Argus, 9 April 1953, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23237689>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[66] ‘Girl in escape from Vic home’, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 27 July 1953, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49272204>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[67] ‘Girl in gaol again’, Argus, 3 August 1953, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23259485>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[68] ‘He has faith in girl’, Argus, 4 August 1953, p. 7, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23259722>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[69] ‘Laborites to visit Gaol’, Age, 13 September 1952, p. 5.

[70] Victoria, Report of the Mental Hygiene Authority, for the year ended 30 June 1952, p. 6. For more information, see Belinda Robson, ‘From mental hygiene to community health: psychiatrists and Victorian public administration from the 1940s to 1990s’, Provenance: the journal of Public Record Office Victoria, Issue no. 7, 2008, available at <http://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2008/mental-hygiene-community-mental-health>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[71] Victoria, Report of the Mental Hygiene Authority, for the year ended 30 June 1953, p. 40.

[72] Victoria, Report of the Mental Hygiene Authority, for the year ended 30 June 1954, p. 285.

[73] PROV, VPRS 1411/P0 Index to Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 109, and VPRS 3994/P0, Units 141 and 142. No correspondence files were located for the index and register entries relating to this issue.

[74] VPD, Session 1952–1953, Vol. 241, 16 September 1953, pp. 934 and 935.

[75] Ibid., pp. 945 and 946.

[76] ‘Girl “not in manacles”’, Argus, 22 September 1953, p. 3, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23323204>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[77] He added that Jill’s injuries were ‘in no way related to mistreatment by the gaol staff’, see ‘How the girl was injured’, Argus, 23 September 1955, p. 1, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23315450>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[78] ‘Problem girl back in gaol’, Age, 23 September 1953, p. 4.

[79] ‘Something on our conscience’, Argus, 24 September 1953, p. 2, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23319979>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[80] ‘Family takes Pentridge girl’, 12 October 1953, Argus, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23309475>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[81] ‘Big scheme for child welfare’, Argus, 1 October 1953, p. 4, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23322783>, accessed 1 September 2015; ‘New secretary of child welfare’, Argus, 6 November 1953, p. 4, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23309884>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[82] ‘Inquiry on Victorian ALP may end on Friday night’, Argus, 1 December 1954, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23441888>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[83] ‘New ALP calling 37 to fight state seats’, Argus, 9 April 1955, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71875403>, accessed 1 September 2015. At the state election in May 1955, Barry led the new ALP (Anti-Communist) Party against Cain – child welfare was not a prominent part of its campaign policies, although Barry did promise to provide finance ‘to abolish the worst features of Pentridge gaol’, see ‘What he promised’, Argus, 7 May 1955, p. 1, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71880976>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[84] Osmar White enlisted in the AIF in 1941 but was ‘man-powered out’ by Sir Keith Murdoch to become a war correspondent, according to Garrie Hutchinson. See the blog post ‘Osmar White’, 19 March 2013, in Remember Them, available at <http://garriehutchinson.com/2013/03/19/osmar-white/>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[85] Beechworth Mental Hospital was criticised as a ‘dumping ground’ in the Stoller Report on mental health facilities and needs of Australia, released in May 1955. ‘Dr Stoller shocked by mental hospitals: Victoria best-equipped, but still short of desirable standards’, Age, 9 May 1955, p. 5.

[86] Osmar White, ‘To find this girl shelter State brands her INSANE’, Herald, 30 April 1955, p. 17. All articles from the Herald in 1955 cited in this article were accessed as newspaper cuttings in Series 4/10 of the Teresa Wardell Collection at University of Melbourne Archives.

[87] On ‘moral panic’, see Judith Bessant, ‘Described, measured and labelled: Eugenics, youth policy and moral panic in Victoria in the 1950s’, Journal of Australian Studies, Issue 31, 1991, pp. 8–28.

[88] Ibid., p. 12.

[89] Osmar White, ‘Jill, the certified girl, gets home offers’, Herald, 2 May 1955.

[90] ‘Tragic story stirs social workers: Church heads call for action on “Jill”’,Herald, 5 May 1955.

[91] Norval Morris, ‘Jill’s story HAD to be told’, Herald, 8 July 1955.

[92] Osmar White, ‘New outburst means … Jill inquiry must go further’, Herald, 25 May 1955.

[93] ‘Girl who was branded insane: Ministers issue statement on “Jill”’, Herald, 3 May 1955.

[94] ‘Osmar White answers ministers: Inquiry urged into Jill’s plight’, Herald, 4 May 1955, p. 7.

[95] ‘“I did all I could”: Galvin’, Herald, 6 May 1955.

[96] ‘Ex-minister says: Change to mental law needed’, Herald, 4 May 1955, p. 3.

[97] ‘“Jill doing well at Beechworth” – says official statement’, Herald, 17 May 1955.

[98] ‘The “Jills” need help’, Herald, 18 May 1955.

[99] ‘Doctor says: Jill is charming, worth saving’, Herald, 28 May 1955.

[100] ‘“Jill” is out of danger’, Herald, 3 June 1955.

[101] ‘Jill’s story HAD to be told’, Herald, 8 July 1955.

[102] ‘Jill back in Beechworth’, Herald, 7 July 1955.

[103] Osmar White, ‘Life began and ended in tragedy’, Herald, 10 September 1955.

[104] ‘Jill, the girl of tragedy, is dead’, Argus, 10 September 1955, p. 1, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71694486>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[105] ‘Life began and ended in tragedy’.

[106] ‘Jill asked: “Why have I been forsaken?”’, Argus, 6 December 1955, p. 1, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71784380>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[107] ‘She’ll keep up Jill fight’, Argus, 12 December 1955, p. 5, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/71785803>, accessed 1 September 2015. My research in the print media, the Chief Secretary’s correspondence or in VPRS 8787 – Alphabetical Subject Index to General Correspondence Files (Mental Health) has found no evidence of any inquiry instigated by Marjorie McDonald in 1956.

[108] ‘Incompetence, brutality alleged. Social worker assails ward’s handling, death’, Age, 12 December 1955, p. 3.

[109] ‘What was Jill’s problem?’, Argus, 24 December 1955, p. 4, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71788274>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[110] ‘To the editor: social worker defends “Jill”’, Herald, 19 December 1955.

[111] ‘They’ll help children’, Argus, 1 September 1955, p. 3, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71692885>, accessed 1 September 2015; ‘“Bread and water” goes’, Argus, 25 November 1955, p. 5, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71782345>, accessed 1 September 2015; ‘Our drifting teenagers’, Argus, 23 December 1955, p. 7, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71788130>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[112] ‘Locked up children’, Argus, 2 December 1955, p. 7, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/71783818>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[113] VPD, session 1955–1956, Vol. 246, 4 October 1955, p. 761.

[114] Ibid., p. 749.

[115] PROV. VPRS 1411/P0, Unit 109, Item 11156, November 1955. This entry in the Index to Inward Registered Correspondence reads ‘juvenile delinquency research committee and Jill case. A matter for the CWD’.

[116] Advisory Committee on Juvenile Delinquency (Victoria), Report of the Juvenile Delinquency Advisory Committee to the Hon. AG Rylah, MLA, Chief Secretary of Victoria, presented at Melbourne, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1956, p. 86.

[117] Ibid., p. 88.

[118] Ibid., p. 89.

[119] See ‘Submission by the Government of Victoria’, p. 6. Children’s Court Act 1956, available online at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/cca1956176/>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[120] PROV, VPRS 4723/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence IV, Unit 310, Item B12692 – Juvenile Delinquency, files relating to Juvenile Delinquency Advisory Committee.

[121] ‘Education’, Argus, 31 December 1955, p. 12, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71789316>, accessed 1 September 2015. The word ‘cheesepare’ is a figure of speech which means to save money, see entry at Oxford Dictionary, available at <http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/cheesepare>, accessed 8 September 2015.

[122] Last year an investigation by the Victorian Auditor General concluded that ‘there has been a fundamental failure to oversee and ensure the safety of children in residential care’, ‘Residential Care Services for Children’, March 2014, p. vii, available at <http://www.audit.vic.gov.au/publications/20140326-Residential-Care/20140326-Residential-Care.pdf>, accessed 1 September 2015.

[123] ‘“I did all I could”: Galvin’.

[124] A range of resources about Winlaton, including memoirs and testimony from former residents, is available from ‘Winlaton (1956–1991)’, Find & Connect web resource, available at <http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/vic/biogs/E000192b.htm>, accessed 1 September 2015.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples