Talk by Anna Kyi for History Month 2022

Produced and recorded by Public Record Office Victoria for the podcast series 'Look history in the eye'

Music by Jack Palmer

Transcript

Anna Kyi

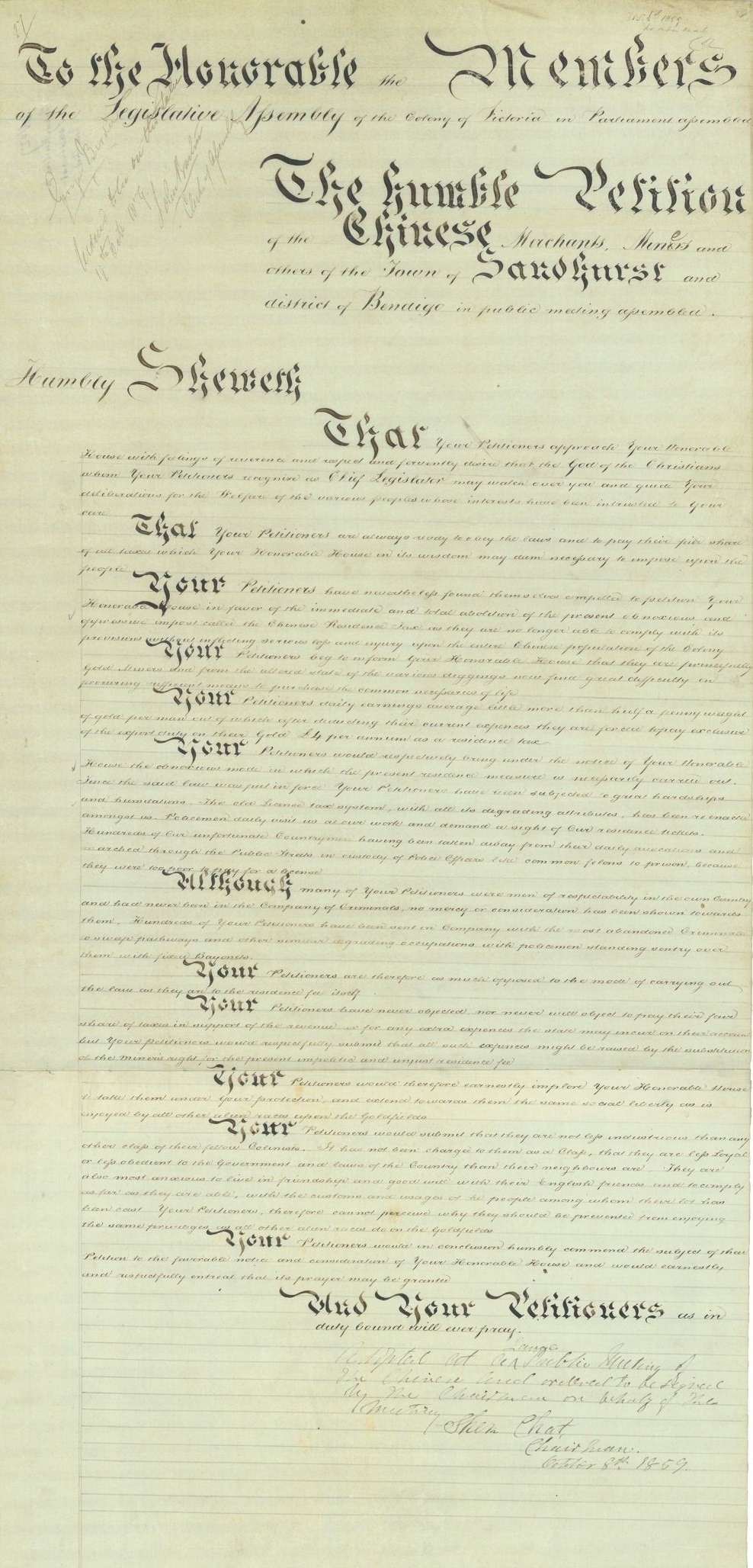

“Policemen daily meet us at our work and demand a sign of our residents tickets. Hundreds of our unfortunate countrymen have been taken away from their daily avocations, and marched through the public streets in the custody of police officers like common felons to prison because they were too poor to pay for a license.”

Kate Follington

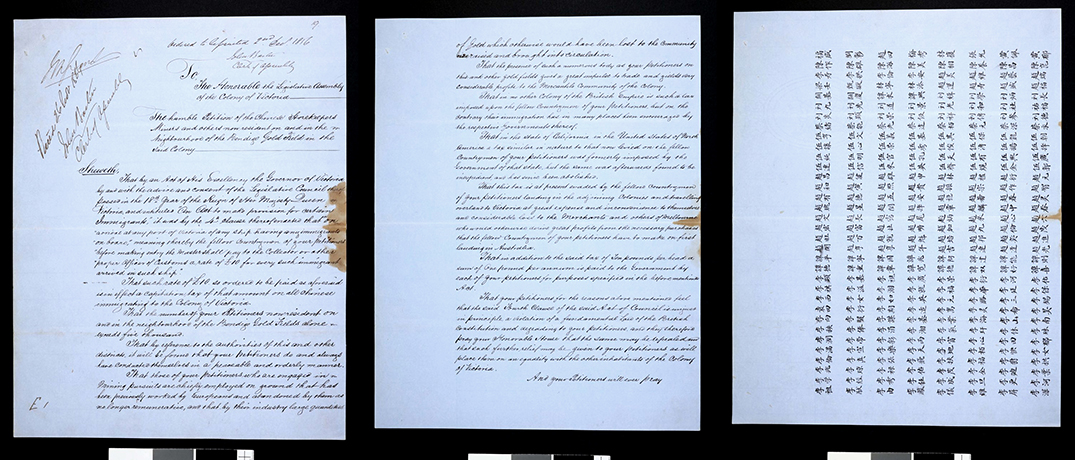

These are the words written on a significant archive found in the Victorian state collection. It’s a petition from Chinese gold diggers complaining of unfair conditions on the goldfields. Our Chinese ancestors came to Australia in search of gold, and like many Europeans, they came in the mid-1800s, however they faced harsher conditions, higher taxes and constant racial tension. Things really flared up when they demonstrated their alluvial mining skills, finding gold on the surface soil or they were also particularly skilful at sifting through the tailings of abandoned mines. By 1858 an estimated 33 thousand Chinese were working the goldfields in Victoria, which is not a small number given the entire population of the state was around 500 thousand at the time.

My name’s Kate Follington and you’re listening to the Podcast Look History in the Eye produced by Public Record Office Victoria, the archive of the state government. One hundred kilometres of public records about Victoria’s past are carefully preserved in climate-controlled vaults. We meet the people who dig into those boxes, look history in the eye, and bother to wonder, why.

Anna Kyi is our guest today, and she’s an historian from Sovereign Hill Museum in Ballarat and she’s written several articles on why Chinese petitions preserved here at the archives are important in understanding the voices of our Chinese ancestors and their fight for equality.

This episode is a recording of a presentation Anna did alongside the original petitions which we put on display for History Month in 2022.

Anna Kyi

The Chinese immigrants who came here to seek gold, predominantly came from an agricultural background. But they did participate in mining during agricultural like seasons so they weren’t entirely inexperienced in terms of mining and their use of water in terms of washing gold and accessing the gold, shallow alluvial gold, from an agrarian background would have come in useful as well. Some of them probably would have come from China as well from the California gold rushes so experience there. So the Chinese immigrants weren’t entirely inexperienced in alluvial mining. In quartz mining perhaps, but not alluvial mining. And the thing about shallow alluvial mining, it was called easy gold, because it required very little skill, you didn’t require a significant amount of capital to get involved, you had to buy a shovel, pan, maybe a wheelbarrow, a puddle bucket, there wasn’t that much money involved. So that’s why it’s portrayed as that democratic metal because anyone can have a go at doing it.

The Chinese were not just seen as an economic threat, they were also considered to be a cultural threat as well. Recognising these fears and concerns about the Chinese immigration, the Victorian Government took steps to restrict the number of Chinese coming into the Colony and to discourage them from coming here.

If you arrived in Victoria in 1855, you would have been expected to pay a ten pound immigration tax on landing now that’s even before you have a chance to start to look for gold. When you arrive on the goldfields, you would also be expected to live in a separate Chinese protectorate camp and pay for a protection ticket. On top of that you also, like all other miners, were expected to pay for a miners right. You could avoid the immigration poll tax by landing in Robe South Australia and traveling overland. 400 kilometres the journey would have taken you, but it was risky. Many died and many suffered ill health as well.

By 1857, it looks as though things are getting harsher. By this time you can’t travel overland or are discouraged from traveling overland from South Australia because the South Australian Government has also implemented the ten pound landing tax in that Colony. There’s also the introduction of a resident’s ticket. Now, you can’t purchase a resident’s ticket unless you can show proof that you’ve paid the immigration ticket, the ten pound immigration tax as well. So, it’s that attempt to catch those that haven’t paid. And if you fail to pay for a resident’s ticket you could have your mining claim or businesses taken from you. The miner’s right or a business licence were basically null and void if you didn’t have a resident’s ticket. So the penalties are quite harsh.

In 1859 the Legislation’s amended once again and you could be fooled into thinking that it’s becoming a bit easier. The resident’s tax is reduced to four pounds per annum and it’s amalgamated with a protection ticket and the miner’s right. However this reduction is backed up by harsher penalties. Chinese who didn’t have a resident’s ticket could be sentenced to gaol or to do public works.

To get a sense of just how oppressive the taxes were that were imposed on the Chinese, let’s compare it to another tax that the miners protested against in the first half of the 1850s gold licence. Protesting against this licence eventually led to the Eureka rebellion. In the lead up to the Eureka rebellion, the miners were paying one pound per month amounting to twelve pounds per annum. As you can see, in the first year of arrival, the Chinese taxes were on par with the goldfields licence. By 1857, it’s far above that at 18 pounds per annum. And in 1859, there’s a reduction to 14 pounds, however, still not as low or on par with the goldfields licence tax.

So, Weston Bate historian claims that the Chinese were the most fiercely taxed members of the community and they would have been justified in their own Eureka rebellion. As you can see from this cartoon here, which is more likely dated around 1859 or prior to the introduction of the 1859 Legislation, in the minds of the people of the time, they’re making connections to the harsh implementation of taxes that were endured before the Eureka rebellion.

So, did the Chinese protest? Although it’s not an episode of our history that’s remembered to the same extent, or celebrated to the same extent, the Chinese in fact did protest. There were many different forms of protest that they used. They evaded the taxes, they held mass meetings on the goldfields, such as Ballarat, Castlemaine, and Bendigo, and they sent petitions to the Governor and the Legislative Assembly throughout the later half of the 1850s. Now this is when the Legislation’s introduced as well as every time that it’s changed. They also practiced civil disobedience in the latter half of the 1850s round 1859 where they refused to pay the resident’s tax and offered themselves up for arrest. I imagine that this relates to the 1859 Legislation because you can see the Chinese being basically imprisoned in the back buildings there where the previous penalties related to claim jumping or stealing, taking people’s mining claims.

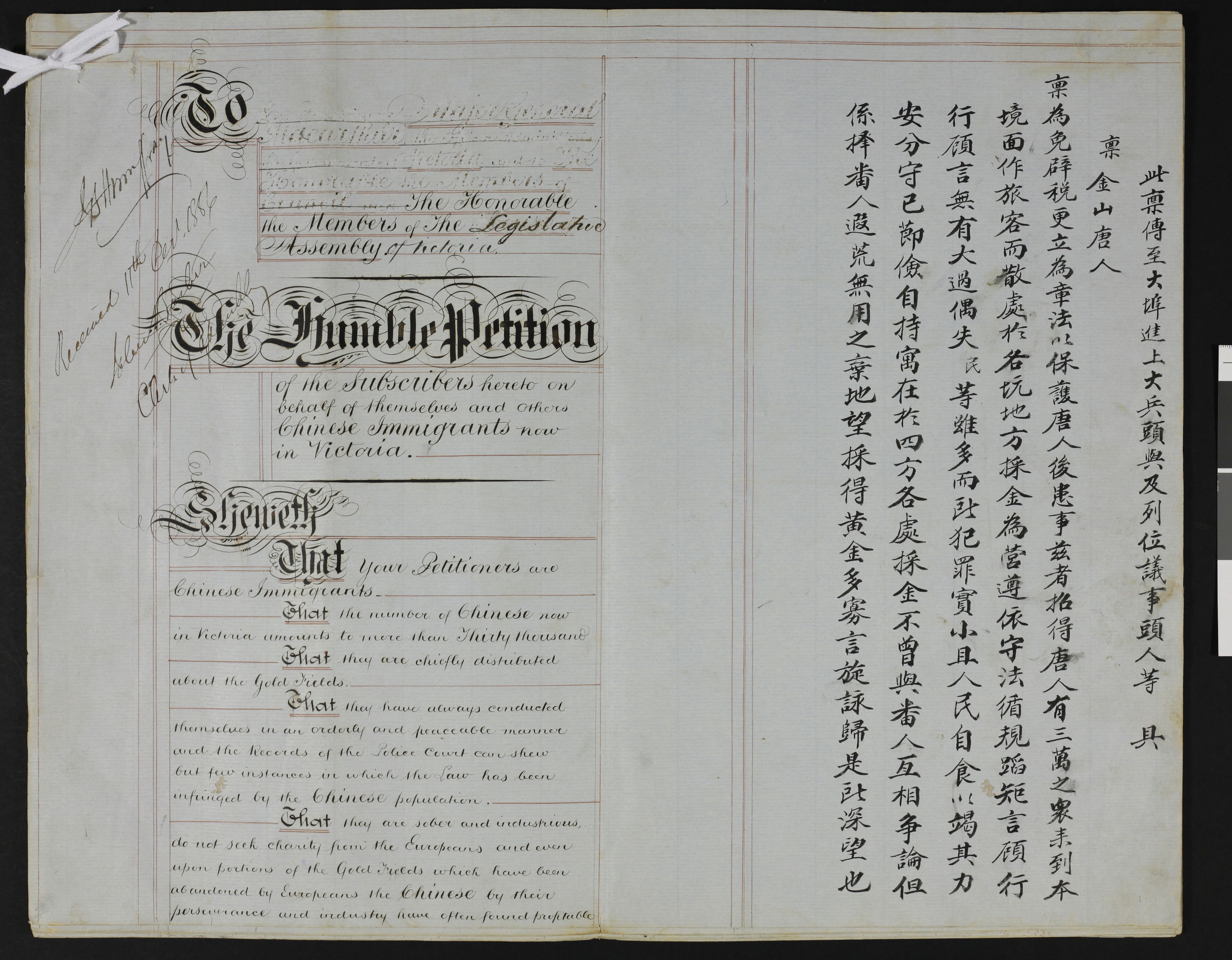

Ok, I’m going to focus on one particular element of the Chinese protests today. The petitions. And these petitions are quite significant because historical records that document the Chinese experience are rare. So what happens is we’re often left with the dominant Western perception of the Chinese. By looking at these petitions, we can see the past through a different lens.

I’m going to focus on how do these petitions challenge racial stereotypes about the Chinese and highlight the diverse experience of the Chinese in Victoria during the 1850s. During the 1850s there was a perception that the Chinese didn’t understand democratic processes and they didn’t have democratic aspirations. So, these petitions challenged this perception in every way. The fact that the Chinese organised these petitions, and sent them to the Legislative Assembly and the Government, and also in terms of their content. They were basically arguing for the right to be treated the same as every other immigrant in the Colony. They weren’t wanting special privileges at all and over the latter half of the 1850s, the arguments that they used to defend this right to be treated equally evolved.

So in 1856 they’re claiming that the laws, the Legislation, are a violation of the fundamental law of the British Constitution that guarantees equality before the law. They also point out that there’s an absence of similar laws in other British Colonies and removal of similar laws in California. So they’re like saying, well you’re the only Colony doing this. And there’s that sense of shaming in a way. In 1857 the Legislation is still seen as a contradiction to British Law and this time it’s merged with a sense of being seen as close to the British identity and British values. So in implementing these laws, they’re saying well how British are you? You’re going against your own values.

By 1859, some of the petitions are arguing that the taxes, the unfair discriminatory legislation, is actually contravening Treaties signed between Britain and China coming out of the opium wars which guarantee reciprocal rights to the Chinese when they visit British colonies. The petitions also, the Chinese also, used them not just to defend their rights but to respond to accusations that were used to develop cultural stereotypes that fuelled the racism. As I mentioned before the Chinese were considered to be an economic threat because they were quite skilled at shallow alluvial mining. As you can see from this particular petition, the Chinese were taking that accusation into account and were explaining well we don’t send that much gold back to China. One person takes a gold parcel for many others. So it’s not that much. And this amount of gold is shared amongst the family. And also again saying well we’re no making that much gold from washing the remaining of the tailings of the gold in the abandoned claims as you think.

The Chinese were also accused of failing to contribute to the economic development of the Colony. Now this accusation came from the understanding that most Chinese were sojourn as they didn’t intend to settle in the Colony and they sent gold back to China. And the fact that China wasn’t a British Colony, Chinese success was painted as theft, they were stealing the Queen’s gold. In the petitions, the Chinese answered back to this and said we basically can’t afford, the accusation was why aren’t you buying land or farms, things that suggest long term settlement and contribution to the development of the Colony and they’re saying well we haven’t got enough money to buy land or farms. They also claimed that they were contributing to the public revenue, to the economy, by paying all these taxes. Rightly so. Though some were evading it. And they also sought to explain how they benefitted the economy by purchasing goods from China, there would have been a tax on those, and through their consumption of European goods.

The Chinese were accused of unnatural vices and abominable acts. Within the language of this time, this would have referred to homosexual acts and juvenile prostitution. This accusation came about because the Chinese immigrants who came here during the goldrush were overwhelmingly a male population, there were hardly any Chinese females on the goldfields. So, in answering back to that, the Chinese said well where’s the evidence to support these assertions? They also explained the cultural misunderstanding as to why they left their wives back in China. Things like their wives feet being bound so that made it difficult to travel, they couldn’t afford the trip for them to come here, and they also had cultural obligations to look after their elderly who remained back in China.

Chinese were also seen as a moral threat as you can see from this petition from the local court in Fryers Creek they said gambling and other vices too numerous and unfit to mention are rife among them. And there was a fear that these vices, this amoral behaviour would spread to the other parts of the population. So it wasn’t the Europeans fault that they might be amoral, it was the Chinese fault because they were bringing it here with them. The Chinese response to this was, rightly, that well where’s the evidence to support all these accusations? Let’s have an inquiry to either prove or disprove these allegations and then treat people accordingly. And also, again, look at the evidence, the court records will prove that there’s no evidence to substantiate these claims or that the Chinese are any more guilty of crime than other immigrants within the population.

The petitions, besides enabling us to challenge these stereotypes that existed about the Chinese during this time, also enable us to explore some variations within the Chinese experience. If we want to break those stereotypes then we can’t look at the group as one homogeneous group, and we do this by looking at absences and presences so to speak.

In 1858 the Ballarat Chinese sent a petition. This was the only petition for this particular year and the request was quite unique. They weren’t asking to be treated the same as all other immigrants, they were asking for extra time to pay the first instalment of the tax. To understand why the Chinese in Ballarat would do that you have to know that the Chinese in Ballarat would have been involved in deep sinking moving beyond shallow alluvial mining and going into deep lead mining and this would involve significant investment in time, money and energy. So if they had their mining claim taken from them, then it would have been a significant loss. For example Chinese miners working on the red streak lead in Ballarat paid ninety pounds for an abandoned mining claim. They erected machinery in order to go deeper, they were quite successful, and then they had their mining claim taken from them the day after the Legislation came in to place. So significant losses for the Chinese in Ballarat because of the type of mining that they were involved in, where on other goldfields they weren’t necessarily involved in deep lead mining.

Differences also emerged between the Chinese in Melbourne and the Chinese on the goldfields. In mid 1859, Chinese in Bendigo, Ballarat and Castlemaine, sent petitions to the Governor, so to Melbourne, the Chinese on the goldfields are asking for a reduction in the tax, while Melbourne Chinese request an exemption of the residents tax. They were basically saying we don’t live on the goldfields where we’re expected to live under a Chinese Protectorate system so we shouldn’t have to pay for a tax that funds a system that we don’t use. Fair enough argument.

By late 1859 they’re sending petitions to the Legislative Assembly. The Chinese are asking for the removal of the residents tax, it’s just far too harsh and they can’t pay, and the Melbourne Chinese requested a reduction in the residents tax and the removal of the immigration pole tax. Now to understand why the difference in request you would have to recognise that the majority of Chinese in Melbourne were either merchants, artisans or traders so they’re regularly traveling between China and Victoria, and in doing so they have to pay that ten pound immigration tax every time they enter the Colony so that’s more of a significant burden for them.

The petitions the Castlemaine and Bendigo Chinese sent in 1859, late 1859, also tell us how harsh and difficult the circumstances were on those particular goldfields. The Bendigo Chinese said:

“The old licence tax system with all of its degrading attributes has been re-enacted among us. Policemen daily meet us at our work and demand a sign of our residents tickets. Hundreds of our unfortunate countrymen have been taken away from their daily avocations, and marched through the public streets in the custody of police officers like common felons to prison because they were too poor to pay for a license. Hundreds of your petitioners have been sent in company with the most abandoned criminals to sweep pathways and other similar degrading occupations with policemen standing centry over them with fixed bayonets.”

And the conditions in Castlemaine weren’t much better than that either.

When we explore the Chinese protests one of the questions that inevitably comes about is were the Chinese successful? Did their protests lead to the removal of the discriminatory Legislation? The Legislation is eventually, is gradually dismantled in the early 1860s. By this time the Chinese immigration population in Victoria has declined but the Chinese aren’t paying the taxes and so they’re rendering the system inoperable because the taxes pay for the Protectorate system to operate in the collection of the taxes. So, while the petitions may not have been effective in helping the Chinese remove the discriminatory Legislation, they’re extremely important to us today, they’re a powerful tool in understanding this Chinese voice, the Chinese perspective which is quite rare to gain a glimpse of during the 19th century.

I can’t remember off the top of my head, but one of the largest has over 5000 signatures. I think that’s the Bendigo one, which is quite a significant level of support. Others are around 3000, 2000, but if you go to the article Finding the Chinese Perspective it lists how many Chinese signatures are in each petition and where you can find them as well, because some of them were published in Parliamentary papers and others weren’t and some you can only find in newspapers. It’s a bit of a jigsaw puzzle to try and get them all together.

Kate Follington

You’ve been listening to the podcast Look History in the Eye. To search for Chinese petitions in our catalogue, you can search for Look History in the Eye online or simply type in Chinese petitions on our catalogue.