Credits

Presenter. Kate Follington, Manager Audience Engagement, Public Record Office Victoria

Guest 1. Dr Alexandra Roginski. Historian and author Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World: Popular Phrenology in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand

Guest 2. Grahame, guest re phrenology reading 1957.

Guest 3. Edward Santow. Professor at University Technology Sydney and Co-Director of the Human Technology Institute.

Guest 4. Christopher O’Neil. Research fellow at the Monash University node of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making & Society (ADM+S).

Audio Clip 1 & 2 from Youtube. Published by British Pathe, Florodora. 1931

Audio clip Clip 3 from Youtube. Published by ABC TV archives. This Day Tonight. Executive Wives. 1971

Transcript.

Phrenology and AI Transcript. Episode 13. Look History in the Eye podcast.

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

people, phrenology, Colin Campbell Ross, facial analysis, arcade, Melbourne, fortune telling, phrenology, data, algorithms, analysis, emotion, person, influence, head, claim, case, working,Gurkha, machine learning.

SPEAKERS

Dr Alexandra Roginski, Christopher O'Neil, Podcast Presenter Kate Follington, Professor Edward Santow, Dawn Burton, This Day Tonight ABC News Archive ‘Executive Wives’, Grahame, British Pathe archive ‘Floradora’ 1931 Daly Theatre George Graves and Lorna Hubbard.

Kate Follington 00:02

If you're one of millions of Australians who recently downloaded the government application called My gov to access government services on your phone, you would have noticed the use of facial recognition technology being used to identify you. The application had used voice recognition before, but now you can put your face to the camera and the application will scan your face to ensure your use of facial recognition technology is developing at record speeds. And it's mostly being used to identify us for our passports or for within crowds. But there's another form of facial technology which claims to move beyond identification. But in fact, to scan our face and describe our characteristics or our emotions as well. And this type of technology is called a facial analysis technology. And you're probably wondering why I'm talking about technology when this podcast is actually about history. The reason is, because this is not a new idea. In fact, for almost a century, there were people who claim to study faces and head shapes, and then offer insights. It was called phrenology.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 01:06

The phrenologist just calls up people on stage. He or she might be blindfolded, for example, to really show that they're not, they're not basing their assessment on any kind of visual marker. They are just working with their hands and using their skill to read the shape of the head.

Kate Follington 01:25

And it was delivered in many forms with some very dark implications. Today we walk through the seedy world of arcade phrenology in the 1920s, we meet one of Melbourne's most enduring Phrenologists infamous Russian mystic Madame Gurkha and we speak to technology experts about computerized facial analysis, and we'll find out if it's any less deceptive than the highly controversial days of skull studying and make believe.

My name is Kate Follington. And you're listening to the podcast Look History in the Eye produced by Public Record Office Victoria the archive of the state government. 100 kilometers of public records are preserved in climate-controlled vaults. We meet the people who dig into those boxes, look history in the eye and bother to wonder why. You can see records related to this story by searching look history in the eye podcast online.

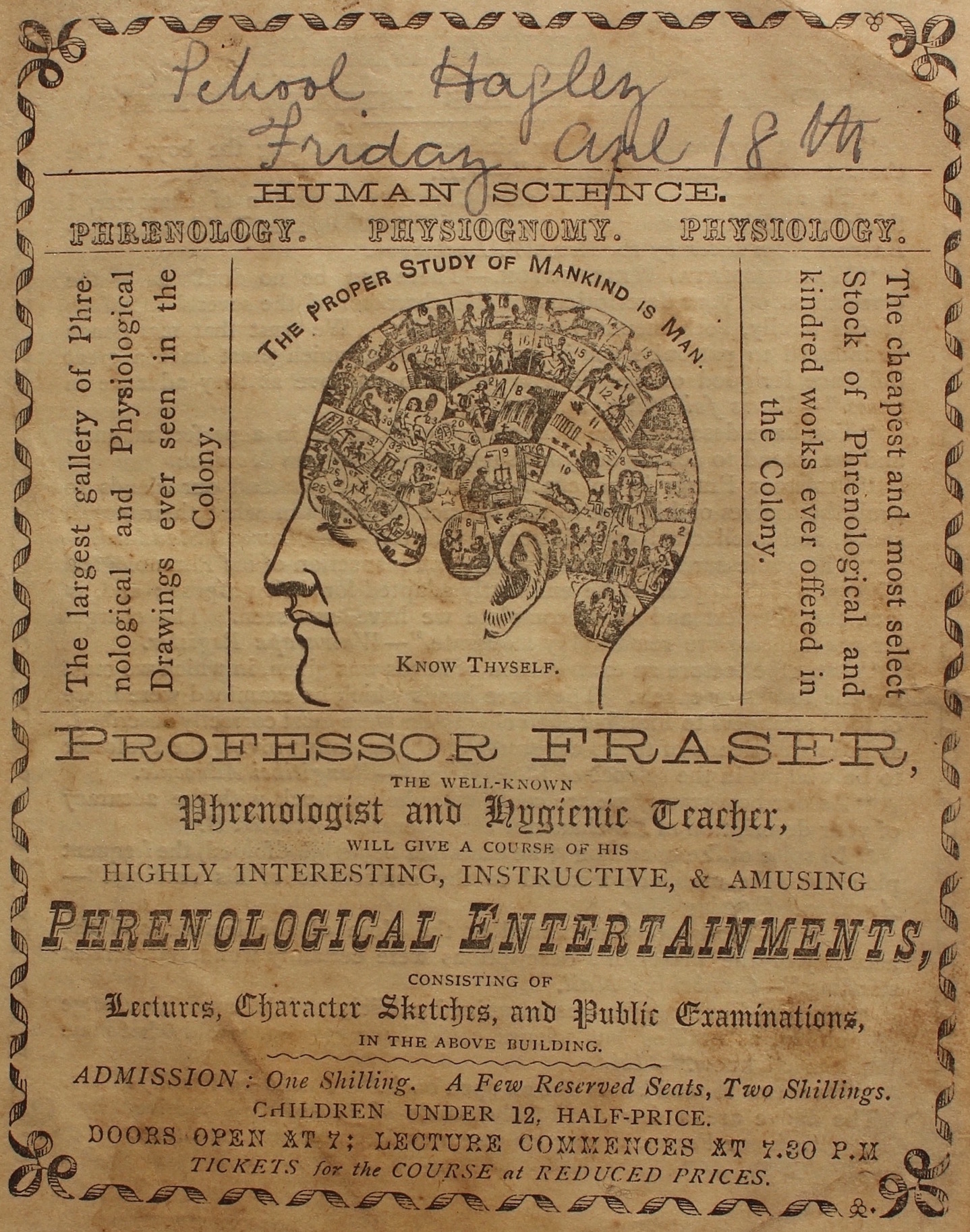

Phrenologists practiced a now discredited form of Popular Science and they claimed that character and your intellect could be judged from your head shape. This was in the 1800s and well into the 1900s they covered a wide range of subject matter and they would often deliver their findings to quite a public audience, kind of like in public lectures or, on the streets of Melbourne something like a busking performance.

Floradora 1931 Daly Theatre George Graves and Lorna Hubbard 02:59

George Graves: My name is Tweedlepunch, Anthony Tweedlepunch, phrenologist and scientist, my card if you may.

Charles Stone: Now my dear, we hall see who nature intended you to marry.

Lorna Hubbard: I know already. Shall I? Is it safe?

Charles Stone: Certainly my dear do as papa tells you to.

George Graves: Now please m’lady may your remove your hat?

Lorna Hubbard: I thought science was above most trifles.

George Graves: Science is above most trifles, but phrenology lies beneath the hat.

Kate Follington 03:28

There were black Phrenologists, European mystics and bellowing creative entertainers. They came in all shapes and sizes.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 03:35

You might go along on an evening to the Mechanics Institute or perhaps the Athenaeum, you know, there were instances where people you know, climbing through windows and really trying to cram in, because this is the talk of the town and there might have been a bell ringer. Handbills were handed out that this lecturer is coming.

Kate Follington 03:56

Alexandra Roginski has published her PhD, a whole book on Australian and New Zealand Phrenologists and their influence on understandings of the of the brain and also of popular culture.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 04:09

So depending on how earnest they are, they would you might have a very long lecture about the different organs of the brain. And they talked about the brain being divided into different sections that was organs, and that would lecture at length on organs, that often talk about how persecuted they were as scientists and that this was the right you know, the right and only true science and that kind of thing, standard padding, and then you'd go into the public readings. And this was, in a sense, a great test of the phrenological skill. This is a time when scientific inquiry is quite participatory. So the audience feels that they're going to make up their own mind, right. They're going to watch this and they're part of the experience of deciding and validating the truth or falsity of this thing. So, you know, they call up people on stage. He or she might be blindfolded, for example, to really show that they're not. They're not basing their assessment on any kind of visual marker, they are just working with their hands and using their skill to read the shape of the head and then they'll pronounce to the audience this person is this or that. And the audience might cheer or laugh or, you know, there's a great deal of laughter, it’s a total Carnival.

Floradora 1931 Daly Theatre George Graves and Lorna Hubbard 05:41

Perfection stands out like a policeman smit. Corroboration on the other side. And I see domesticity, developed also. What a cook, what a cook! What a mutser mixer.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 05:53

It was devised as a system at the end of the 18th century by a Viennese physician. And he was quite serious about dissection and part of this great period of inquiry into mind and brain and how it fit together. Were we just the product of our brains? Or were we also influenced by spiritual or other forces. So, it comes about in this time of neurological inquiry, it's really debated and contested as well as a lot of ideas were. It also comes about at a time of interest in comparative anatomy. So different human differences. Those seen in Europe and people from you know, encountering other parts of world questions about, you know, how deep do these differences go?

Kate Follington 06:47

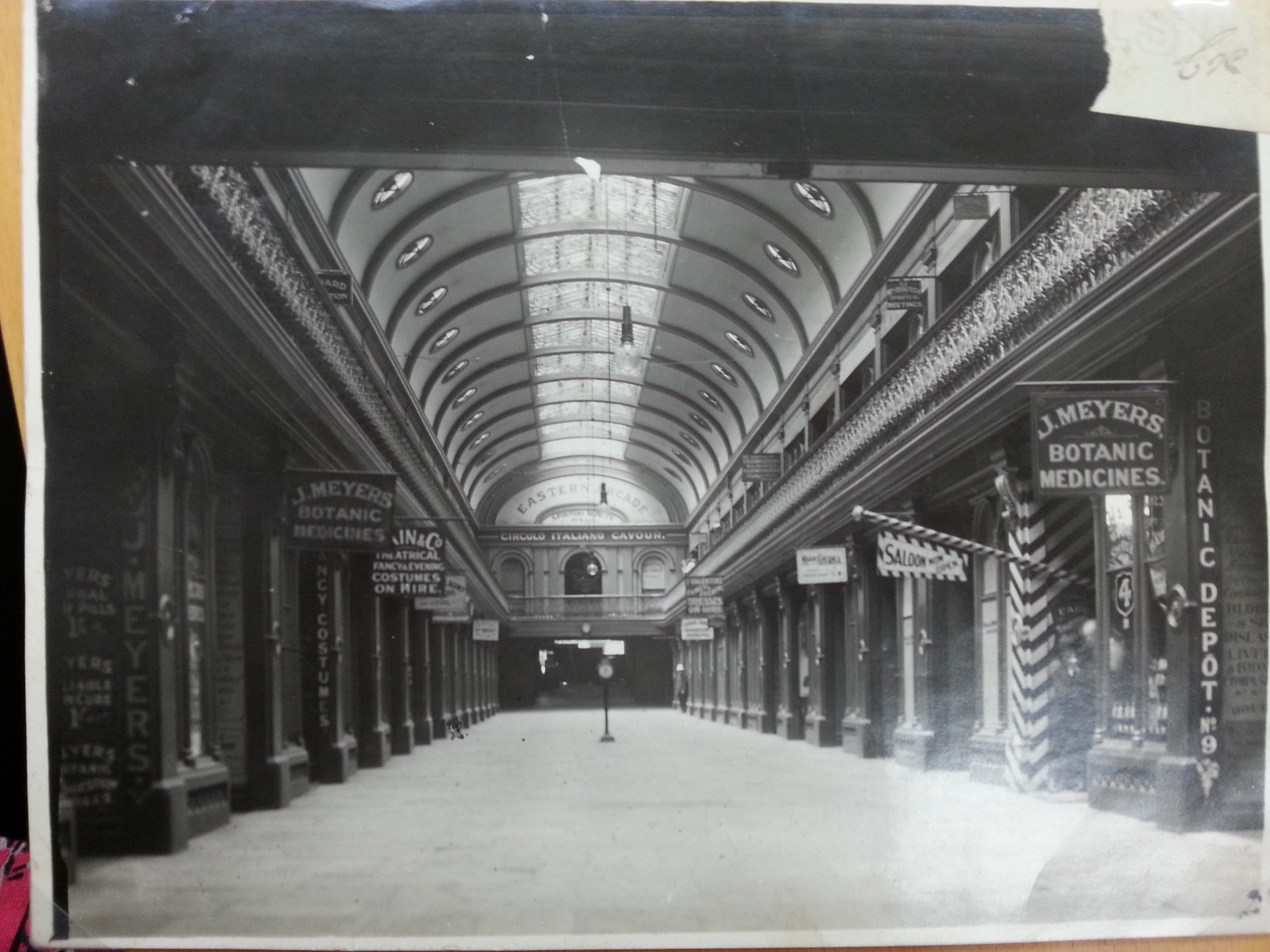

By the 1920s. The lecture hall entertainers were being upstaged by moving pictures, and the era of cinema was taking over. So phrenology was pushed into other spaces, like the Eastern arcade, an exotic area of the city of Melbourne, on the corner of exhibition and Russell Street. It had an impressive Middle Eastern and Moorish facade, the balconies were framed by pointed archways, similar to a mosque. It was an exotic escape for the young and the curious, where the fruits of Orientalism could be enjoyed for fun. It was designed to be alluring for leisure seekers.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 07:26

It’s tantalizing, it's different. And this is why a lot of the fortune tellers and Phrenologists and various diviners in this space and in the eastern arcade, were giving them themselves made up names that sounded exotic, so you might have someone called Annie Cartwright or Annie Stevens who goes by the stage name of Zinger Lee, or as you do, yeah, Madame Zambra, Madame Zingara, these kinds of sibilant names those people sounding exotic, often wearing what they think of as gypsy costumes gypsy dress, and it's a bit of a world of theater and make believe it's various costume yeas and dressmakers is dress up fancy dress higher. There's Vaudeville artists. There's a wine shop, because alcohol and coffee consumption were always part of this world as well. There's an Italian club, there's a spiritualistic seance hall. There's a herbalist, and my entry point into this are the Phrenologists.

Kate Follington 08:43

Fortune tellers offered a bit of everything, from women needing marriage advice to herbalist tonics for arthritis. And while they may have visited for the tarot card reading the sign outside their shop fronts often would say they were Phrenologists. And there was a reason for this, Fortune Telling was forbidden and phrenology was seen as more legitimate.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 09:06

fortune tellers were thought of as having power to tell people to leave their spouses, for example, to disrupt the social order that was seen as having an influence. That was, yeah, corrupting people at a time when there's a lot of concerns about working class behavior that women's behavior, women facing a prosecution for. And this apply to vagrancy laws in general. So someone who you could be locked up for being on the street and not having an occupation. And that person would say, I do have an occupation. I'm a phrenologist, because there was something you could just assume and kind of do on the side. But these young women are generally saying, I'm not a fortune teller. I'm a phrenologist. That's a science. It's a very old science. If you don't understand that, then like you've got a lot going on.

Kate Follington 10:01

It’s hard to talk about phrenology in Melbourne without mentioning Julia Glushkova. She upstaged them all. She was a character reader and Melbourne's, mostly during and reputation at least phrenologist. Arriving in Australia at the end of the first world war in 1917, her infamy reached new heights when she was linked to a murder case that was still being heard within the Melbourne judicial system. Right up until recently.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 10:32

She was actually a Russian migrant who earlier in her life was known as Julia Glushkova. And she seems to have been born in Odessa. But she was half Welsh and emigrated to Wales in 1882. And the circumstances surrounding that emigration, depending on the story, she’s telling, depending on the reporting, that she had thrown a bomb at the horse and carriage of a local notable figure and that this was in retribution for her brother dying. Whether or not this meant she was a revolutionary, it was something that she contested. But she leaves the country and goes to the UK to live with family relatives. They're so that she gets married. She has a son called Alex Olson, Alexander Olson and a daughter called Violet, she husband dies. she remarries a man called Henry Gibson, Henry Gibson's a vaudeville performer. They have four sons, and they end up in Australia at the end of the First World War, and she ends up with rooms in the eastern arcade. She is also a Phrenologist and a character reader. Other people might say she's a palmist and a fortune teller.

Kate Follington 12:10

Madam Gurkha wasn't one for truthful claims. She claimed in one newspaper report that she was shot when she was working as an agent for the British Secret Service. However, during that interaction, she still managed to kill the son of a Russian General. This claim was then fiercely denied by her husband who admitted that he was he you accidentally shot her during a circus performance in Russia.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 12:36

She's also accused at a certain point of being an abortionist, which is a matter she sue's over. One thing you can say is she's very canny. It's I think it's really worth noting that in 1918, her husband, Henry Gibson, he wants her to give up her business and move with him to the country. Pretty classic. abuse dynamic, he comes in and smashes up her shop display cases in her shop. She brings this civil case against him and he's basically ordered to stay away from her.

Kate Follington 13:12

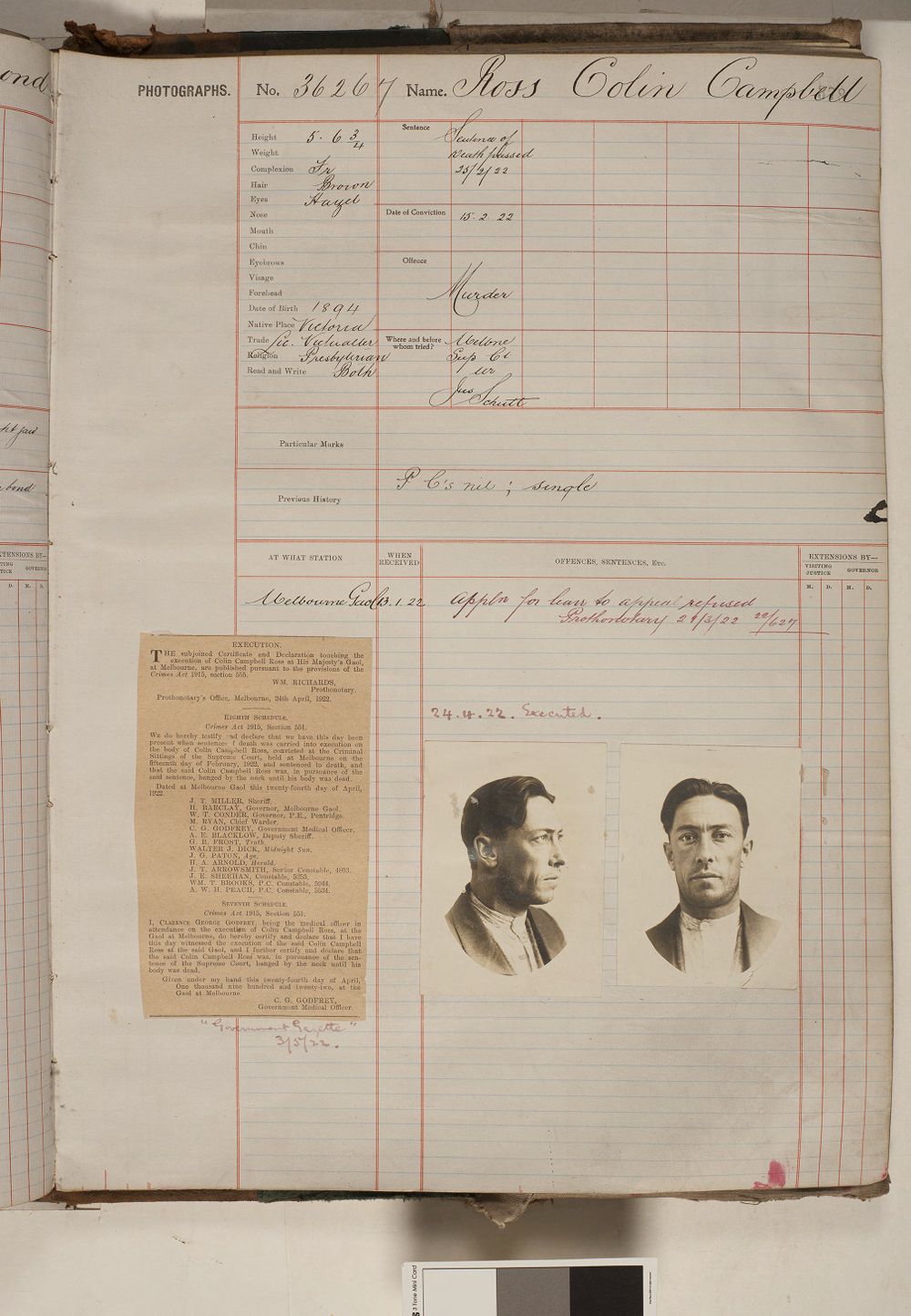

By 1921 Madam Gurkha, is a single mother of four children running businesses which might get her arrested. But regardless, fortune telling or phrenology, in all its various forms, is worth the risk. She's even renting out a flat to Ivy Matthews, a woman who's working the wine bar in the arcade. The wine bar is owned by a man called Colin Ross, and it's called the Australian wine saloon. But the bar is not liked by the other retailers because it's attracting a type of clientele who urinate on the floor, and verbally abuse people coming into the arcade. So, it's fair to say that the bar owner Colin Ross, wasn't liked by Ivy Matthews or Madam Gurkha. And eventually Ivy is fired. And this is where things get really messed up. It's 1921 and the two of them seize upon an opportunity to help frame Ross, it's a really sad case, which ends up haunting Madame Gurkha and the Melbourne judicial system for another century. It's the murder case of 12 year old Elma Tirtschke, otherwise known as the gun alley murder.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 14:27

On the 30th of December 1921, she is sent by her grandmother from the grandmother's home in Jolimont to pick up some meat from the city. And she goes to the butcher. She has seen wearing a distinctive blue skirt and white blouse and as ribbons and she ends up around the location of the Eastern arcade scene with her brown parcel. And various people see her she does didn't come home that night. And the next morning, she's found her body is found in gun alley, which is a small laneway off little Collins Street, very close to the eastern arcade. This murder is very shocking. It really shakes up the city, there's a lot of speculation about who it might be. And the police end up arresting Ross and prosecuting him. And the evidence really hinges on the testimony of three people, one of whom is Ivy Matthews, and the other is a sex worker called Oliver Maddox, who is also associated with that place and knows Ross. And the other is a man of awaiting trial in jail who claims that Ross when he's on remand makes this confession to him in very lurid and awful details. So they they're claiming that Ross confessed to the crime, that it was part of her passion that he had pedophilic tendencies basically, that testimony together with hair sampling. So this is an early instance of hair sampling used in forensic context, and it’s used to convict him. But there's a very strong case made by the barrister who publishes the book about this, that Ross has been wrongfully convicted.

Kate Follington 16:38

Colin Ross is found guilty by jury and is then hung in April 1922. The case is closely followed by the media and the public, in particular the Herald, who also offer a financial reward to solve the crime. So that reward is then shared among Yes, you guessed it, Madame Gurkha and IV Matthews, along with other crown witnesses, many of whom were even staying at Madame Gurkha’s home during the trial. If you are interested in the gun alley murder, there are several detailed books and newspaper articles written about it. And you can find those at the State Library Victoria, along with the court files which are held here at The Public Record Office, and they're digitized.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 17:20

But in the late 1990s, the hair samples which were in the records from the Ross case, they're taken to the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, and they're sampled. And these are not the same hairs. So the hairs that were snipped from the head of Alma Tirtschke, are not the same hairs as those that are found on the blankets that had been in Ross's possession.

Kate Follington 17:49

So he's ultimately exonerated.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 17:51

He is Yeah, posthumously and it does cast the role of this network of people who testify in this case, that contribute to his conviction and Madam Gurkha, as one of the puppet-masters within that group in a very different light.

Kate Follington 18:19

So, while we have on the one hand on the very fringes, Phrenologists, and palm readers working in the seedy underbelly of the arcades, at the same time, there's also a more palatable, if not equally insidious form of phrenology emerging within the middle classes in the early 1900s. And this form of phrenology then contributes to a conversation about what makes the ideal Australian. And during the early 1900s, that person was a white male, born on Australian soil.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 18:52

so there’s a shift during the 19th century from what is known as an environmentalist approach, which says that, you know, where we look different because of the environments that we live in, but actually, we're one community of man, to this much more kind of fixed idea that develops and gains traction during the 19th century, about racial difference, and that racial difference is physical, but it also has, you know, signs of things inside and signs of mental capacity.

Kate Follington 19:27

The long-term legacy of phrenology, the pseudoscience, you might say, is it overlapping and commonly linked to Eugenics. Those Phrenologists who attempted to idealize white European heads over any other cultural ancestry, describing others as inferior due to their head shape.

Dr Alexandra Roginski 19:47

so phrenology does become also a form of racial science. Very importantly, this is why we have skull collections collected by Phrenologists that include Australian Aboriginal ancestral remains, for example, those of other people in America were used very much in thinking about people of African heritage as well. So, it has those darker connotations. We've also got the social reformers, what we would think about or think of as the small l liberals of the day the progressives. So, in the early 19th century, there's a group established at the Athenaeum. They're called the Phrenological and Health Institute of Australasia. They have a magazine called Mind and Body. People who are pulling the levers are middle class women involved with a Women's Christian Temperance Union, say, who see phrenology as playing a role for social improvement in terms of guiding people to behave in the right way.

Kate Follington 21:02

I should add here that their organizational photo is similar to any early 20th century sepia toned group photo of conservative looking women neatly dressed in long skirts and blouses pinned to the neck, their long hair pulled up into a neat bun standing among well-manicured men with neat moustaches and three piece suits and polished shoes. Except for one thing. They're holding human skulls in their hands, like some weird Gothic dress up party.

Kate Follington

Was there a link to the white Australia idea?

Dr Alexandra Roginski 21:40

Yes, there is a very deep undercurrent of white supremacy in all of this, often unspoken. But if you look at who the focus is on for improvement, it is a concern about the white race about who are Australians? How can we make them as strong and robust as possible, and a concern with organizing society in a way that produces the best stock.

Kate Follington 22:21

By the late 1920s, phrenology begins its decline as psychoanalysis is gaining steam. Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung are presenting their groundbreaking ideas about the study of psychoanalysis, and this idea that we're influenced by our past and that we have a subconscious mind. Phrenologists begin to rebadge themselves as psychologists and they begin to use more elaborate language, psychoanalytical language in their readings. What is our lifeforce? Are we introverted? Are we extroverted? Do we fit into Jung's eight archetypes? Amazingly, Phrenologists continued to operate in Australia, right up until the 1960s. Mostly employed by large businesses to assist in their recruitment processes or to offer vocational advice on behalf of parents. Like Graham who in 1957, was sent as a 16 year old along to Heighwood Masters to have his bumps read.

Grahame 23:21

He said I have three main abilities a good eye, good construction skills I can look at things from a practical point of view, and a good profit making sense. And he went on from there, I suppose but I was influenced by the fact that he said I should take up public speaking to give me you better use of words and give me confidence. Confidence. Yes, he suggested going for a career in banking. I must have mentioned architecture, I must have mentioned that particular to a because I don't remember him asking me many questions about myself. Except my name, address, how old I was. And I must have mentioned, what I wanted to do for a living. Really first the bank I wanted to be an architect. And I had to top school and graphic drawing.

Kate Follington 24:17

rather than the head reading perhaps it was the confidence that he gave to you the belief in you as a person.

Grahame Clift 24:25

I think it also suggested I develop confidence, because I lacked confidence, and I should take up playing competitive sport. Which I did, I joined the golf club for example.

Kate Follington 24:42

Graham is not alone in feeling a positive impact from personal analysis. Let's face it, many people feel personality surveys provide some worthy conversation starters. Regardless of the credibility of the science behind the analysis. Sometimes it's just a spark you need to motivate some change, I think it's fair to say that it was a guiding head that Grahame needed, not a head study. Believe it or not, but during the 1960s, top executives from Australia were going along to see Phrenologists and even sending their wives along for advice on how to be a good executive.

This Day Tonight ABC News Archive Executive Wives 25:16

Mrs. Burton has the table set at 10 o'clock in the morning for tonight's dinner party. But there was a time when she didn't manage so well. And her husband suggested she should do something to become a better executive wife.

Dawn Burton 25:27

Yes, as a matter of fact, he had done something himself about being a better executive, and he'd gone to a phrenologist. A phrenologist is a person that puts his hands through your hair, feels your bumps, and then sits back and enjoys conversation with you. And then helps you adjust your way of thinking. So your husband suggested that you should do this?

Yes and maybe I'd like to do this because other executives wives had more or less had an inspection from this person.

Kate Follington 26:00

We are now well into the 21st century, and there’s a new phrenologist in town. This time, the hands that fill our heads to draw conclusions are touchless. They're analyzing our faces with screen-based cameras and spitting out their findings based on mass data sets. And while we sit at the very early stages of artificial intelligence and machine learning, there is emerging a new form of technological deception, akin to the phrenologist of the past. And this is why governments are seeking regulatory guidance on how to ensure that computers and their machine learning software, don't begin to promise insights beyond identification, and claim things about our character, or emotional states, which are simply untrue.

Edward Santow 26:45

There's a lot of experimentation that has been done on other forms of facial analysis. Perhaps one of the most infamous examples of that was a team of researchers in the United States at Stanford University, who did this controversial experiment where they took a large number of photographs from a dating app Grindr, which is particularly used by people in the LGBTQ community. And what they tried to kind of use a machine learning algorithm to do was to identify the characteristics associated with people who might be say, gay or lesbian. And then when a new photo was put before the machine, it was asked, you know, is this person likely to be gay or lesbian. And that's a really concerning example. Yes, that was done in an experimental scenario, it wasn't being done, as we understand it to make decisions that would affect people's legal rights. But nevertheless, if that sort of application were to get into the wrong hands, we will be really worried, one, it’s just incredibly sensitive information, and the system didn't work very well. But the idea that someone's sexual orientation would be revealed by something about the facial structure. I mean, that is the very kind of essence of phrenology is the science behind that is just plain wrong.

Kate Follington 28:26

That's Professor Edward Santow. He's the Co-director of the University of Technology, Sydney's human Technology Institute, his team are working on identifying the gaps where legislation is not sufficient to control how technology may be used to analyze us as people and identify us and influence decision making.

Edward Santow 28:47

The thing that is most impressive about machine learning is that it will pick up patterns in the data, it will pick up the sort of characteristics associated with apples, you know, the first sort of colors, texture, that will store that sort of thing. And it will also pick up the characteristics of patterns in the data associated with oranges. And so over time, if you show the machine a new picture of an apple or an orange one that has never seen before, it should be able to look for those patterns, and then be able to correctly identify whether it's an apple or an orange. So that's the idea behind machine learning based image recognition. So the thing about facial analysis is that it relies on exactly that technique. So let's say what you are trying to do is use facial analysis to determine whether someone is responsible or not. The original sin starts with the labeling, because you still have to give it a whole bunch of pictures of people who are responsible, and label them either responsible or irresponsible. Yeah, exactly. And so you can do that maybe you could maybe say look to the category of people that you want to describe as irresponsible is people, you know, photos of people who have been, you know, sentenced to prison for 10 years or more for terrible crimes, right? So maybe that is the very definition of an irresponsible person. And the, the, the training data for people who are responsible might be people, you know, who have been, you know, awarded prizes for, for doing the right thing, right. So let's just say like, it'd be very difficult to let's just say, for the sake of argument, you could, you could get photos, very large number of photos of people in those two categories would do what I emphasize, that would be incredibly difficult, if not impossible. But secondly, there's, there's the basic problem here, which is what makes someone responsible, irresponsible, has nothing to do with their face, someone is not more responsible, because of the size of their nose, or the placement of the ears like that. Those things are just, they just don't reveal anything about your level of responsibility. And so the problem is that the machine will still find patterns in the data. But they're meaningless.

Kate Follington 31:16

Unfortunately at this point, there is no obligation for companies to disclose the modeling data, that they're feeding into the machines, what photos, what labels, are marked against what data to produce patterns, and then produce analysis. And this is concerning, particularly when the research they're using to train the software is historically problematic, or that permissions to utilize data about us haven't been correctly sought.

Christopher O'Neill is part of research team from the Australian Research Center of Excellence on automated decision making. He acknowledges that facial analysis technology is still on the fringes. It's being used more in America than it is here. But there's some concerning data, particularly data linking facial expressions to emotional states.

Christopher O'Neil 32:07

So emotion detection algorithms, they're mostly predicated upon the work of a psychologist Paul Ekman who was an American psychologist working in the 50s and 60s, he was employed by DARPA, which is the big Defense Research Institute in in America. And basically, they were asking him to try and work out a universal template for emotions. And he conducted what is now considered generally very dubious research, he went to Papua New Guinea, sort of thinking that people who lived in Papua New Guinea was sort of living closer to nature. And so they were kind of closer to like, pure emotion than we were in Australia, or in America, in the West, you know. And so he was kind of using images of these people to try and sort of detect or try and sort of define sort of pure emotional states like this is what purely happy face looks like a purely sad face a purely angry face. And these were, these has basically been used as the templates for trying to determine, you know, what a particular emotion looks like, now this rests upon an extremely dubious idea. One, that there is such a thing as a pure emotional state that is universal, the idea that you and you know, I feel happy in the same way you feel happy in the same way that anybody in the world might feel happy. And also, the idea that there's a universal, you know, language of the face, that we might use to, to express that happiness or anger or stress or whatever, you know, the way we express emotion is, is highly culturally specific, to determine by social norms, and that kind of thing, the idea that there's a one to one relation between the way I feel or the way I am and the way my face looks, is also, you know, basically pseudo-scientific, you know, so Ekman kind of took these kind of core models of, what a particular emotion looks like on the face. And then he took that back to the lab and got grad students to sort of, you know, he'd say, Okay, do a happy face, do a stressed face, do an angry face, and they would sort of perform, But you know, it was sort of highly performative already. They were sort of doing an impression of a happy face. And he would say, yes, great, that's happy. That's happy. That's happy. That doesn't look quite happy enough for me. And this was how they sort of collected the initial data set, that there's models afterwards have been trained on venues to label facial detection algorithms. And the detection of emotion is highly culturally specific, highly racialized, highly gendered, there's been studies that have been done of emotion detection algorithms that have found, they tend to classify, for example, African American people, you know, tend to look angrier according to these algorithms than, than white people do. And so there's a kind of inbuilt sort of sort of central presupposition of the models wrong, but they sort of reinforce racial bias. And this is obviously, you know, a huge problem in terms of if they use it in job interviews.

Kate Follington 35:58

This is the interesting part about human beings. Why do we seek out deception? Why don't we trust our own intuition? Are we so afraid of being wrong, that we would rather blame a machine, we would rather be willingly deceived, because the responsibility of the decision is then placed onto the shoulders of a machine or a fortune teller. We would rather do that than experience the discomfort of a poor decision than embrace the natural chaos of the occasional wind and the occasional fail.

Christopher O'Neil 36:32

You know, generally speaking, if companies buy these applications, they’re sort of told that these algorithms are reliable, to sort of, even if they're sort of spitting out data, that seems like oh, I didn't know I had a bad feeling about this guy, or this guy doesn't, you know, he seems he doesn't seem that happy to me, or whatever. Or he interviewed really badly. And I had a bad feeling about him that the the algorithm is saying is a wonderful person. There's not necessarily any easy way to question these algorithms.

Kate Follington 37:10

I guess it comes down to this idea that we would trust data over our own intuition.

Christopher O'Neil 37:16

there's a term in the literature called automation bias, which people tend to trust automated systems more than they trust their own judgment.

Kate Follington 37:25

Phrenology and any form of insight offered from reading our faces or heads was deceptive a century ago. And it's still deceptive today. Regardless of whether a computer is making that analysis, or Zinga Lee.

Christopher O'Neil 37:40

You can trace back to sort of phrenology the idea that the face is a sort of universal signifier that it's true everywhere all the time, that you can, you know, in in, you know, across cultures and across environments and so forth. But in practice, the face is very unstable, it bears the marker of culture of society and environmental determinants in ways that can be quite strange and quite difficult to predict ahead of time.

Kate Follington 38:21

You've been listening to Look History In The Eye podcast produced by Public Record Office Victoria. If you've enjoyed this podcast, please share it with your friends. And if you are interested in the original records that have motivated this episode, you can go to the website, just type in Look History in the Eye Podcast online.