Author: Kate Follington

At the Melbourne Morgue, On the 13th of March 1936, the State Coroner Arthur Tingate wrote his inquest findings on the cause of death for Doris, a 31 year old woman from regional Victoria who died at Warburton Hydro and Hospital in February. She had been rushed to the hospital from a nearby chalet showing symptoms of cold shivers and bleeding heavily. He reviewed the 15 pages of detailed witness statements and doctors’ notes and tried to piece together his conclusion on what happened to Doris in the final two weeks of her life.

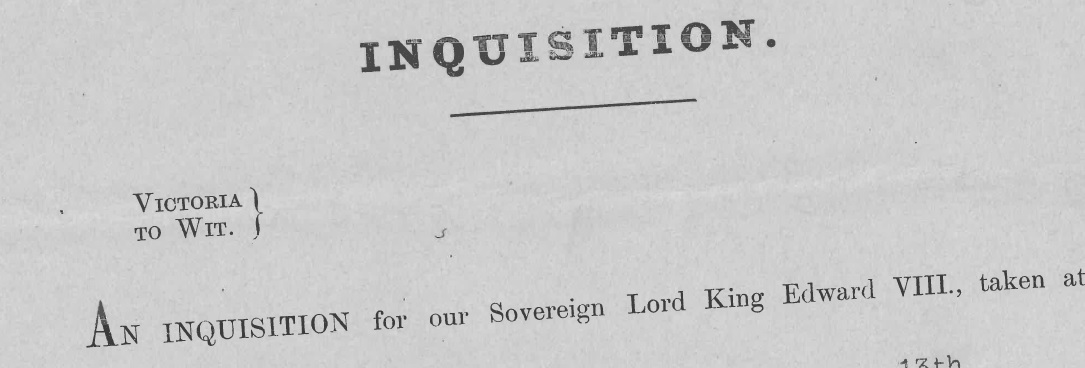

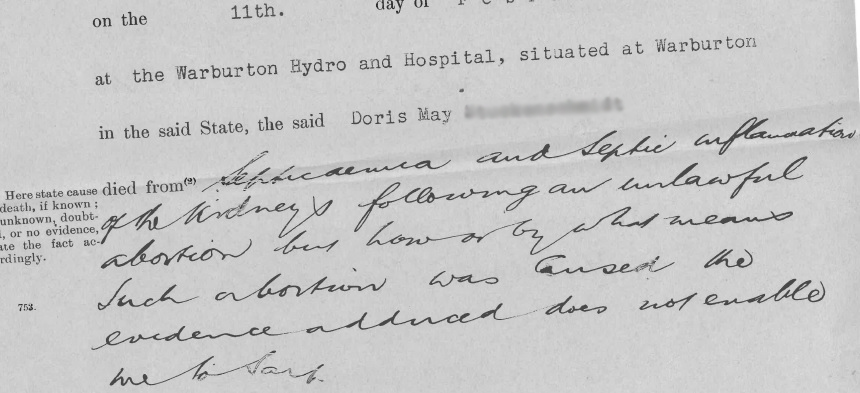

His note on the inquest form concluded, “ Doris ... died from septicaemia and septic inflammation of the kidney following an unlawful abortion, but how or by what means such an abortion was caused the evidence added doesn’t enable me to say.” (1)

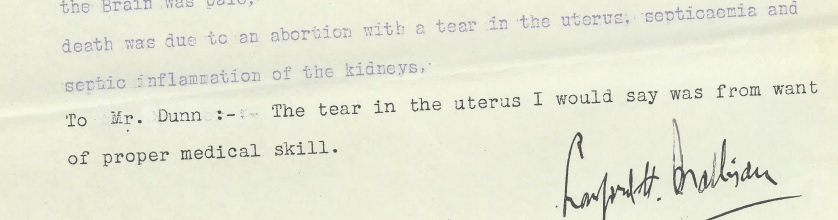

What is also detailed, interestingly, is the post-mortem examination by surgeon Crawford Mollison who not only states the exact cause of death, but also hints that a tear in her uterus may have been caused by an unqualified practitioner.

Did Doris herself inflict that wound, in a desperate attempt to terminate her pregnancy, or did she, as various witnesses testify, visit a doctor or unqualified abortionist and their tardy work result in her death? Either way, her death was not investigated any further. Doris’s story was not atypical of many women in Australia before abortion was legalised in 1969, whose lives were cut short when an attempt to end a pregnancy went wrong.

Her inquest record tells us a lot about her life before death: her day-to-day activities; her love life and family; and, finally, her intimate death-bed conversations, all told through the eyes of others. Inquest records are an excellent source of information for their value in informing social history research as well as family history research.

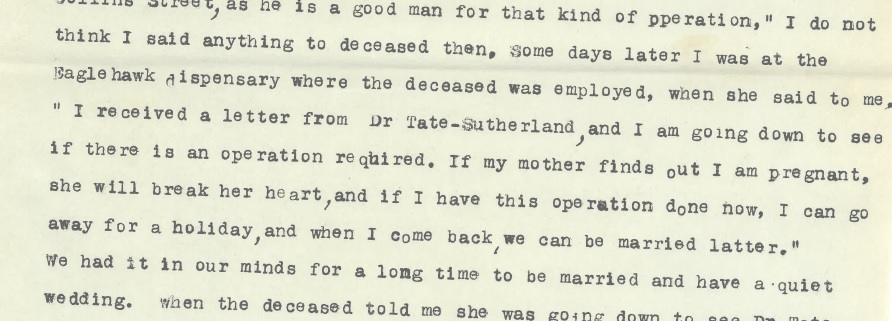

In this particular case, we learn Doris was a well-educated working woman in Bendigo from a well-respected local family. She worked as a chemist’s dispenser and was planning to marry her long term boyfriend Don. She had told him one evening, while they were driving back from White Hills to Bendigo, that she thought she was pregnant, “I have not had my periods this time and I think there must be something wrong with me…I feel worried about it.” According to his witness statement, she had received a recommendation from a chemist, Mr Chamberlain, to visit a doctor in Melbourne and terminate the pregnancy.

Don’s statement to the police, perhaps the most moving witness account, paints a picture of Doris’ worried mindset and the stigma of out-of-wedlock pregnancies in the 1930s.

Visiting her at the Warburton Hospital a week or so later, just a few days before she died, Don claims Doris told him she had visited Collins Street to visit Dr Tate-Sutherland, by then an elderly man and well-known Melbourne obstetrician and abortionist, and she had described the doctor as ‘very cruel’.

Author and academic Janet McCalman, who wrote the book Sex and Suffering, on the history of women’s health treatment in Australia, suspects Doris may not have visited a doctor for the abortion, because a tear was unusual for a qualified obstetrician.

"It’s less likely, but it still could have happened. A huge number of doctors were doing abortions in those days, they were called non-therapeutic curets. One doctor had said that half the middle class women of Melbourne had had a non-therapeutic curet at some stage."

According to Janet McCalman, and countless inquests like Doris’, women would traditionally attempt, often successfully, to terminate their own pregnancies.

"Women used a Higginson syringe, they were hung on a hook in the laundry. They forced it into the uterus, injecting lysol or soapy liquid, to trigger contractions. By inserting something into the uterus though, they could risk a puncture or tear, or if the syringe was dirty an infection would easily start".

The scale of women’s deaths related to illegal or self-induced abortion, prior to it being decriminalised, is hard to quantify. They weren't always investigated and the cause of death may have been attributed to a number of things. The ongoing digitisation of inquest records at Public Record Office Victoria, which registers cause of death including abortion, will offer researchers some insight into abortion-related deaths in Victoria.

Professor McCalman explains it still doesn’t really reflect the reality of the number of women who died.

"No, not at all, many women died in hospital, and their deaths were not investigated. Doctors would often change the cause of death to make the bereaved feel more comfortable. The stigma could be attached to families for generations."

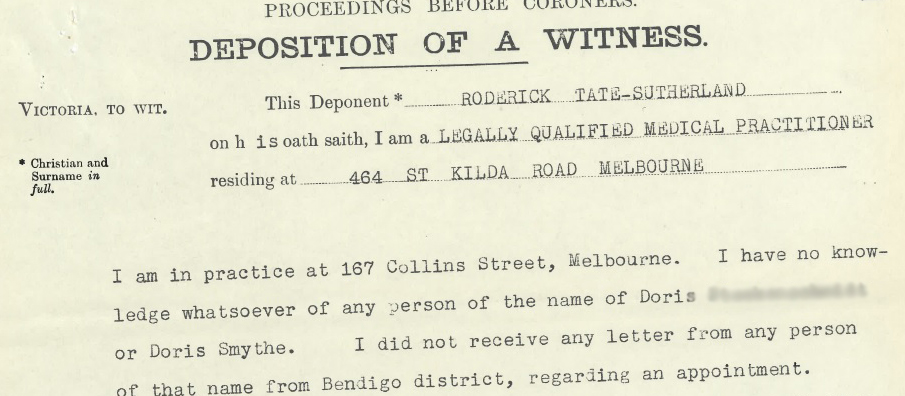

Despite the name of the doctor mentioned by both Doris and her boyfriend, Dr Tate-Sutherland denied any knowledge of knowing Doris, and his denial was sufficient for police to drop any further investigation into Doris' death. Dr Tate-Sutherland was a retired obstetrician and gynaecologist from the Women’s Hospital, and would have been in his seventies when treating Doris. (2)

Unlike many personal records, inquest records up to 1985 are viewable to the public. Conducted by the Coroner, inquest investigations attempt to isolate the exact cause of a person’s death by interviewing witnesses and individuals related to the case, particularly if the death may have been unexpected.

(1) PROV VPRS 24 P0 Unit 1936/1304 Inquest Deposition Files, State Coroner’s Office.

(2) Argus (Melbourne), 14 November 1945, p 3 Obituaries. Sutherland, Roderick Tate (1866–1945)

How to research inquest records

Visit the researcher topic page on inquest records to learn more about researching and viewing inquest records.

Topic Page: Inquest Deposition Files

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples