Author: Jelena Gvozdic

VPRS 16930: important historical pieces, including soldier’s private papers & their family member’s personal records

Records relating to the early Victorian Defence forces are somewhat of a rare finding within Public Record Office Victoria’s collection. The Commonwealth assumed responsibility for all Australian defence forces from 1901, and as a result, many of these records were transferred in to the custody of the National Archives of Australia (NAA). This is not to say that we don’t hold sources relating to the early defence forces, rather that they are hidden away within the records of various government departments, who were responsible for defence prior to federation. Tracing these sources is not for the faint hearted given the complicated cataloguing system of many government department series. Of the records we do have, they often document the central administration of the defence forces. There are also fortunate and surprising instances, where one can view sources of soldier’s private papers, as well as records revealing the impact of the Second Boer War within Australia. VPRS 16930 The Empire’s Patriotic Fund Application is one such series.

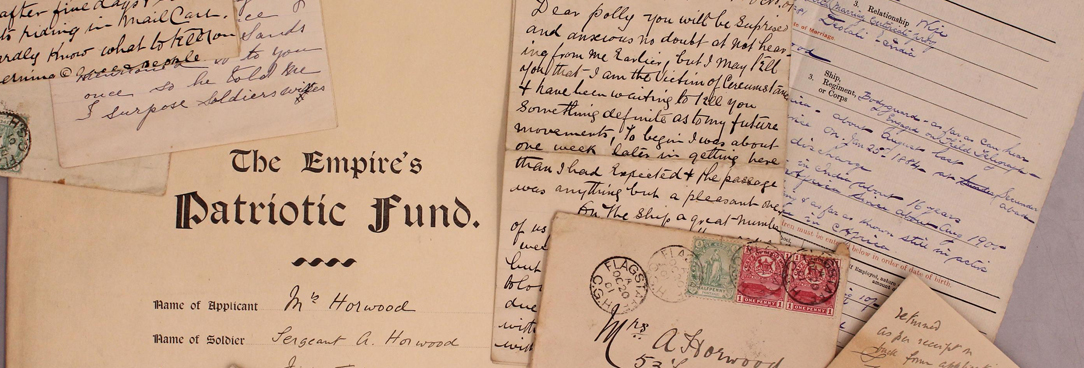

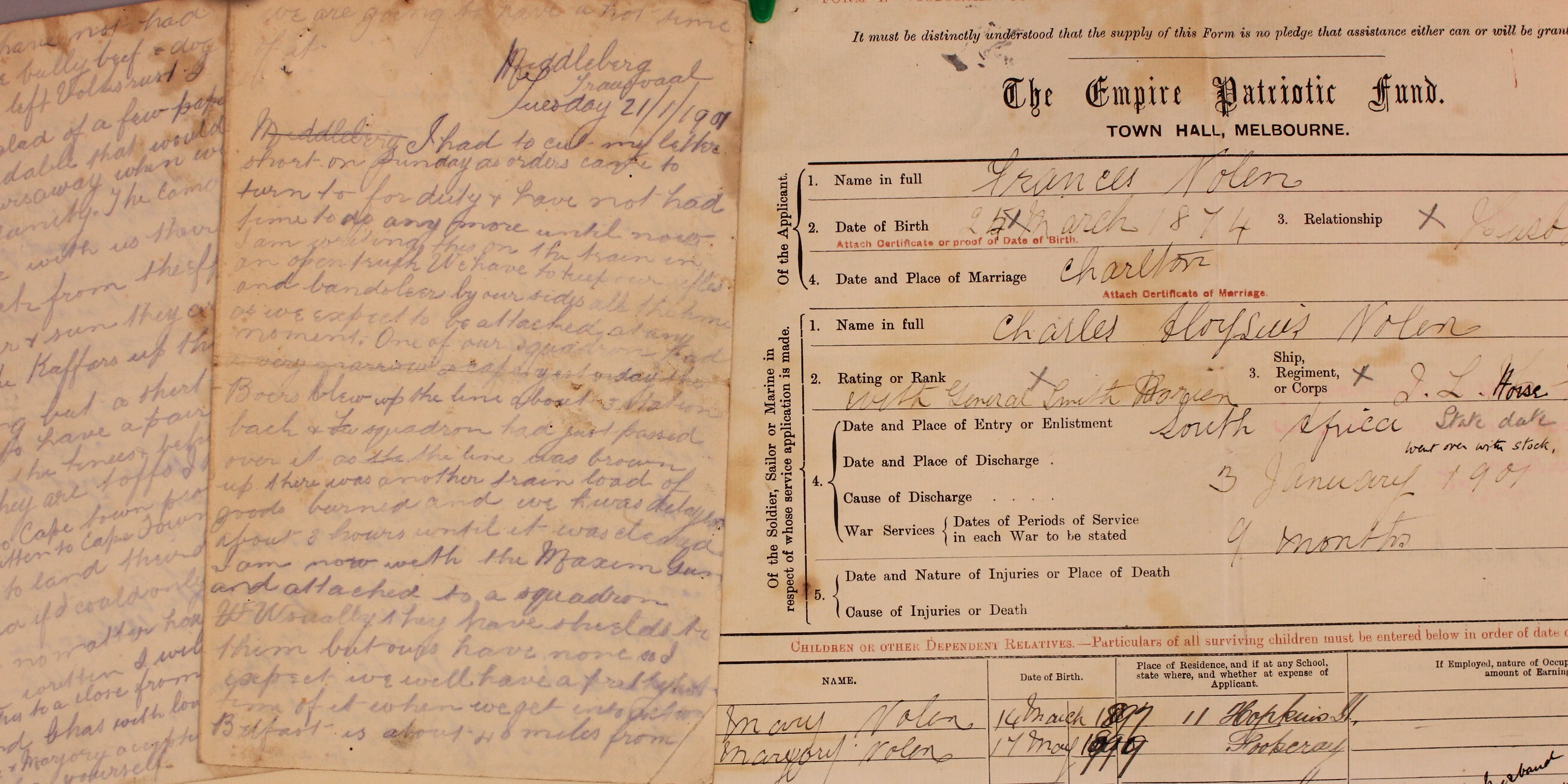

Fig 1 – Some images showing the different articles found in the fund applications.

Several patriotic funds were established across Australia after Britain declared war on the Boers in October 1889. The Victorian Empire’s Patriotic Fund was one which raised almost $65,000 from its beginnings on 9 January 1900. Applications for the fund were mostly made by returned injured soldiers or families of soldiers who were over in South Africa. They often contain supporting documentation - in most cases these are in the form of discharge certificates, doctor’s certificates, marriage certificates or letters of character recommendation. Memos from the Victorian Military Forces, or correspondence between the Defence Department and the fund, are also quite common. At times applicants attached personal mementos; these include letters between soldiers and their loved ones. Surprising and poignant little treasures, no doubt, to their now living families, at the same time they are valuable historical pieces detailing the experience of the Second Boer War from a variety of sources.

In a technical way, the applications show the decision making process of the executive committee, in relation to the disposal of the money raised, and the ways in which they framed or altered bylaws relating to this task. $40,000 of the funds raised was sent to the Patriotic Commission in London in 1900 and the remainder of the monies raised was allocated as grants to Victorian soldiers and their dependents from 1900 to 1918. By 8 November 1918, all monies had been disbursed and the fund was officially disbanded. Although we can be sure that the committee used the utmost consideration for each application that was lodged, there would have been some backlash when grants were refused to applicants. We can see as much in Application 283. Private McNamara wrote a letter complaining that the heads of the Patriotic Fund were granting money to people not by merit of their situation but according to the recommendations attached to their application: “I know myself to be permanently injured, have been removed from your fund, while men who can daily go to work, but who are fortunately more influential than I, are kept on” letter dated 7 October 1904; his daily allowance from the fund had been discontinued after two years.

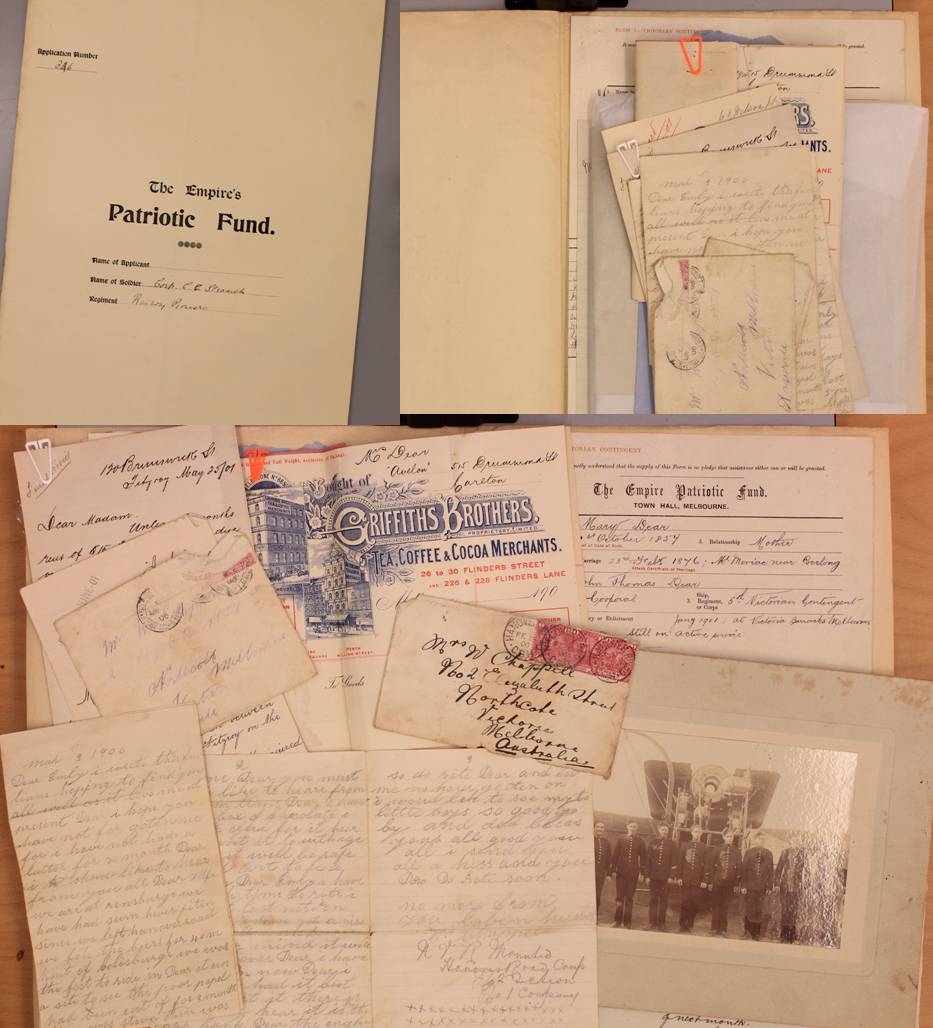

Fig 2 – Application 206 made by the mother of Peter Davies, Fifth Victorian Contingent (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 2)

The series also provides a unique opportunity for us to learn about the Victorian soldier’s experience in the somewhat forgotten Second Boer War. At least 16,500 Australian troops were committed to fighting the Empire’s war. Of the Australians serving, they were either part of the contingents raised by the six colonies, or after 1901, by the new Australian Commonwealth. Many had also made their own way to South Africa, or were already in the country when the war broke out and joined local or colonial units. Some prolonged their service by joining the other colonial or local units, after their enlistment in an Australian contingent ended. Although support for Britain was unequivocal when the war began, the patriotic feelings eventually faded as more and more people at the front, as well as back home in Australia, became disenchanted with the conflict. We find a letter in Application 206, sent by Peter Davies, part of the Fifth Victorian Contingent, writing to his mother on the 25/7/1901 who had applied for some relief from the fund. He writes of his worry for her as he has been unable to forward money back and describes a narrow escape from death. He wishes the war was over, describing it as a hard life and how he thinks “it will tell on some of us in years to come”. Such sentiments are echoed in other letters found within these applications.

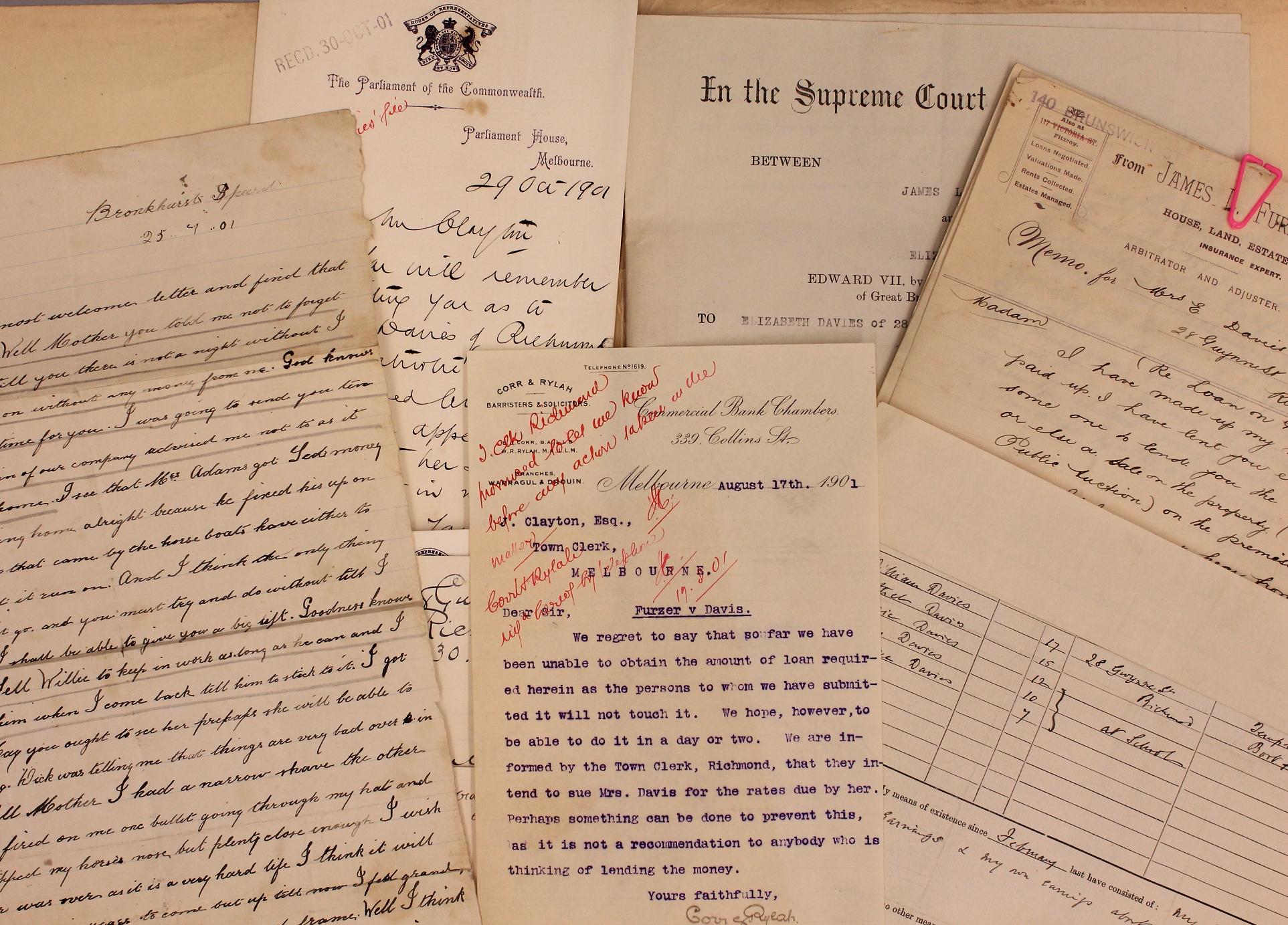

Fig 3 – Section of the letter Peter Davies sent to his mother while he was serving in South Africa (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 2)

Several historians view the Second Boer War as a military and socio-political debacle. The concentration camp and “scorched earth” policy adopted by the British military forces had certainly brought the British Empire under much disrepute. Many Australian soldiers were fighting during this third phase where military tactics were changed to meet the Boer use of guerrilla warfare. Perhaps this is why the Victorian soldier’s letters illustrate a sense of disillusionment with the war. Conflict was dragging on and an end to the war seemed to be nothing but a distant hope. Accustomed to traditional warfare, the British forces had been ill prepared against the remaining bands of Boers. Although the Boer’s army was fragmented, they had formed into groups of highly mobile commandos. After September 1900 many Australian soldiers, seen better able to fight the Boer guerrillas, were either sweeping the South African countryside, and enforcing the British policy of cutting the Boers off from their support by burning farmhouses and capturing civilians, or pursuing the Boer units themselves and attacking their encampments. As the soldier’s letters confirm, the war essentially involved long rides and regular onslaughts from Boar units. Application 249, made by the wife of Thomas Theobold, a member of the Second Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts, describes just this. In a letter to his wife, dated October 20th 1901, he tells of the 2nd Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts troubles during their travels to Pretoria. They were surrounded and ambushed by the Boers, just as they had camped after travelling a far distance. Thomas says that four of their men were killed, fifteen wounded and twenty four taken as prisoners. He speaks of the harsh conditions, dealing with the changing climate and going days without food. Many soldiers died from exhaustion and starvation on the long treks across the countryside.

-

Fig 4 – Application 249, Carrie Theobald also attached a letter sent by her husband, Thomas, from Pretoria in 1901 (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 2)

The letters found in Application 261, made by the wife of Charles Nolen who was part of the Imperial Light Horse, unmistakably illustrates the guerrilla war phase. Charles wrote to his wife Frances in January 1901 from Pretoria. He speaks of the Boer’s tactics having himself passed a station with his unit where there were “200 burned trucks, laying on all along the line there is train wreckage (Letter January 20 1901). Charles describes how the soldiers kept their weapons by their sides at all times as “we expect to be attacked at any moment” (Letter January 21 1901). He recounts that a squadron had a narrow escape the day before: “the Boers blew up the line about 3 station(sic) back & the squadron had just passed over it, as the line was blown up there was another train load of goods burned” (ibid). The railway lines were integral for British military strategy, they carried vital supplies and communication; the Boers were essentially disrupting the operational capacity of the British army. Charles believed it would be some time before the war would be over, although some with him were certain it would only be a matter of months.

Fig 5 – Application 261, the letters sent by Charles Nolen clearly illustrate the tactics the Boer’s used to disrupt the operational capacity of the British forces (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 2)

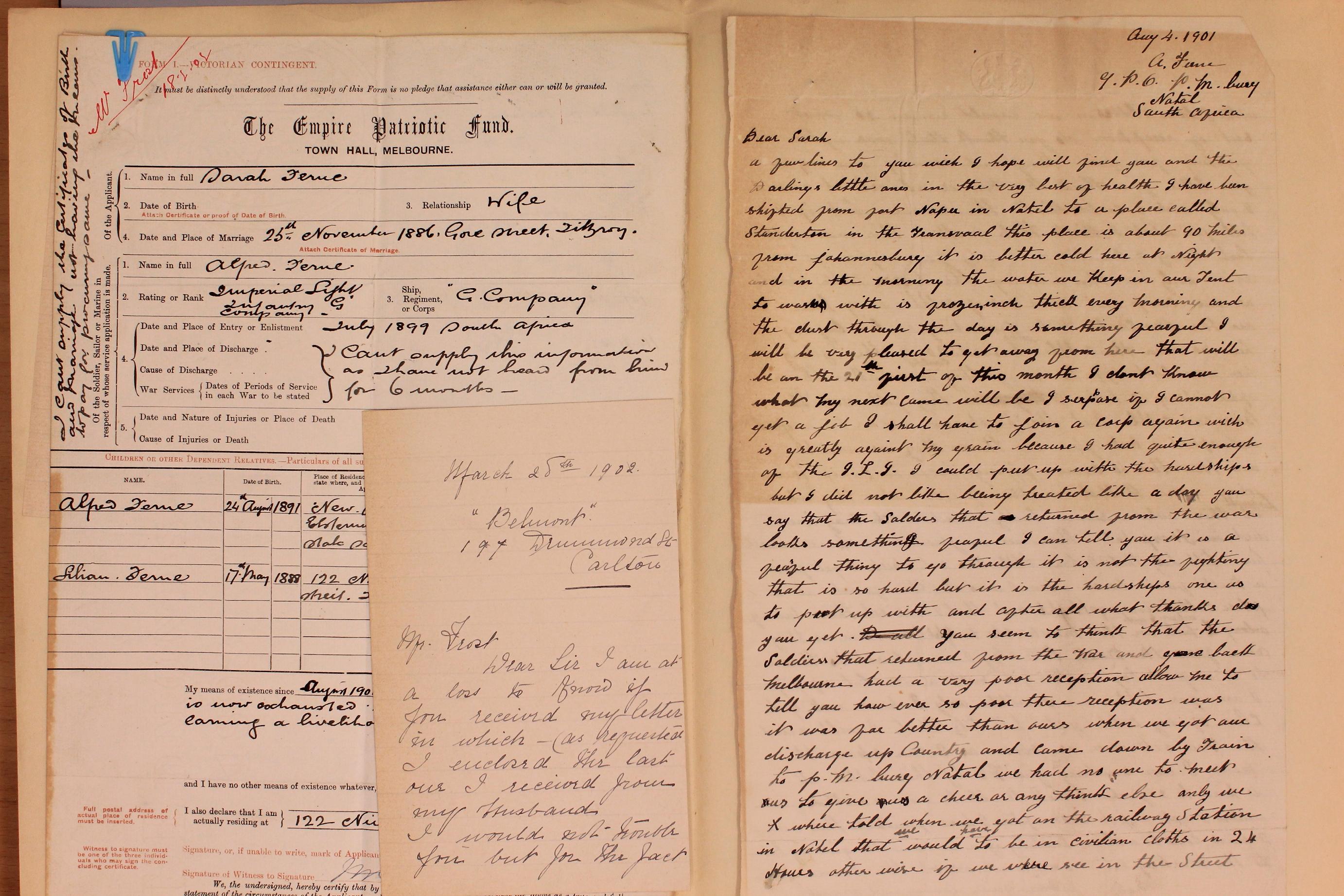

A letter sent by Alfred Ferne of the Imperial Light Infantry, in Application 269, similarly discusses this doubt regarding the end of the war. Alfred writes at a later date, however, in August 1901. He recounts to his wife how the Boers raided his camp some nights prior, clearly indicating that attacks were still taking place and the enemy wasn’t yet thwarted by the British forces. Just as Thomas Theobold described in his letter, dated later in the same year. Alfred’s letter is particularly interesting given the recollections he provides of his treatment while serving in the war. After arriving in Natal he talks about the poor reception the discharged soldiers received. Instructions were given to get out of their military clothing or else risk getting harassed by others in the town, “I could put up with the hardships but I did not like being treated like a dog… I can tell you it is a fearful thing to go through, it is not the fighting that is so hard but it is the hardships one is to put up with and after all what thanks do you get.” He writes this in response to his wife’s letter, informing him of the poor reception many soldiers received upon their return to Melbourne, and how fearful they looked to her.

Fig 6 – Application 269, Alfred Ferne, of the Imperial Light Infantry, writes to his wife while in Natal. He is clearly troubled and disappointed with the treatment of the soldiers. (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 2)

It is true that as the conditions of the camps were becoming public knowledge, there was public outcry both in Britain and Australia. Many women and children were taken to concentration camps and thousands died in these camps from malnutrition and contagious diseases. The reaction and condemnation from the people living in South Africa would have been even more heightened. Britain had essentially sent thousands to fight against an enemy they were convinced they understood, in a war they were certain they could quickly win.

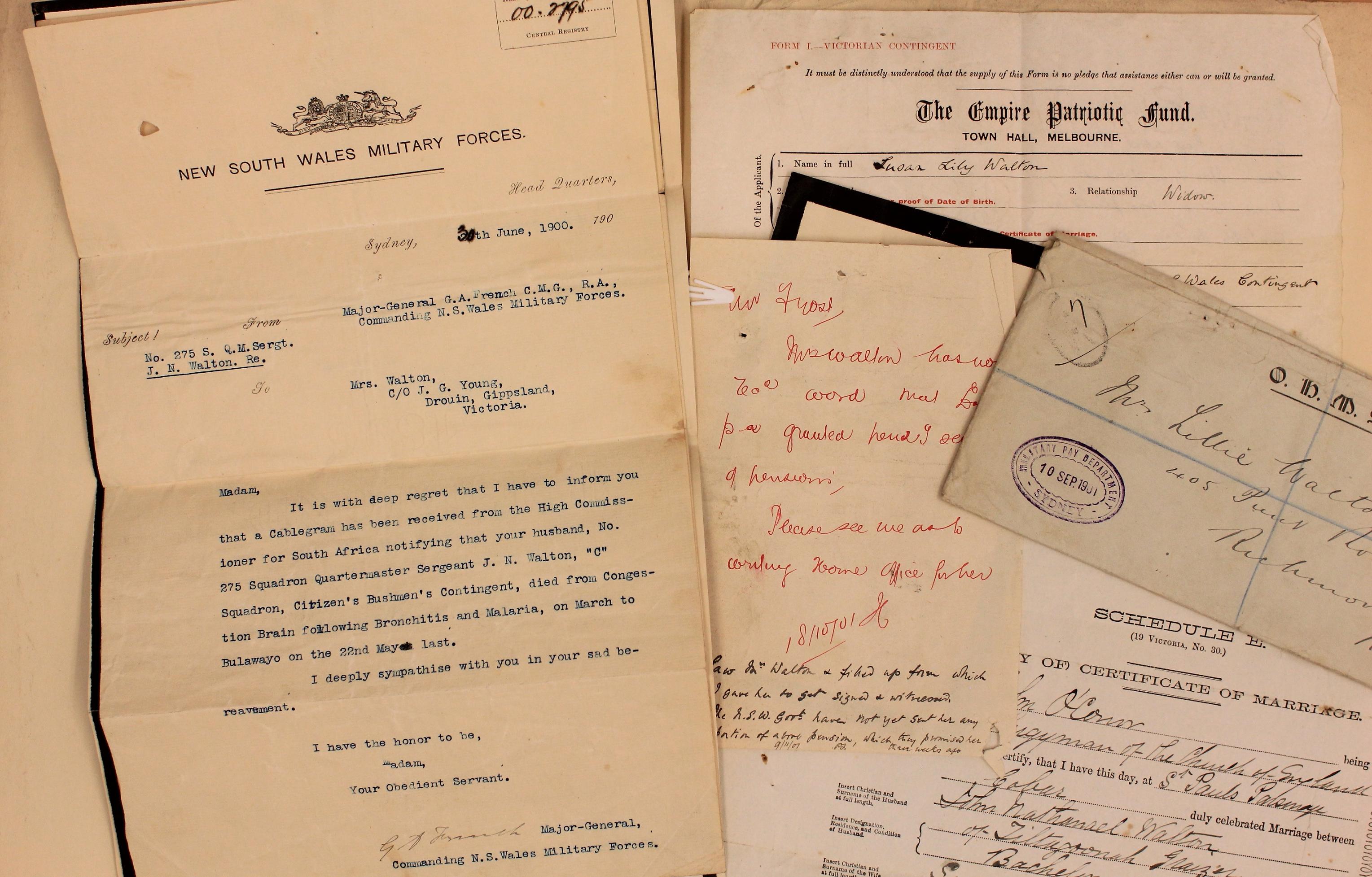

Most had thought that by September 1900, since the British had been able to regain control of many of the territories in South Africa, after winning major battles and capturing the Boer capitals, the war would come to an end. This was not the case, much of the fighting would continue until early 1902 when a treaty was agreed to. It was only by this time that the forces were finally convinced that only peace would bring the war to a close. The Second Boer War was certainly marked with great protest and back in Australia families were also facing personal and financial hardships. Many of the fund applications recount similar predicaments, forwards of payments sent by the serving soldiers were never received, although arrangements were made with the paymasters in South Africa. Pensions for wives whose husbands had died in the war were still being processed by the government, so they were essentially living with no means. Application 302 indicates such troubles; Mrs Walton’s application is accompanied with the actual letter sent by NSW officials informing her of her husband’s death in South Africa. We can read later letters sent by the NSW government advising that her pension is pending, given the question of “Pensions for Widows” is still being decided upon by the government. Many letters were sent by the wives of soldiers, who were forced to sell their furniture, other belongings, or even their houses, simply unable to support themselves and their children.

Fig 7 – Application 302, sent by Susan Walton who has learned of the death of her husband while serving in South Africa and is in need of assistance (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 3)

The aftermath of the returned soldier’s lives is also frequently marked with their trouble to find employment and to be supported after sustaining war injuries. A number were permanently injured. As the sole providers of their families, the help from this fund, as well as other government pension assistance, would have been their only means of existence. The struggles of wartime were certainly felt by everyone, undoubtedly the most to those directly affected by what was taking place in South Africa, the civilians and the forces of both sides.

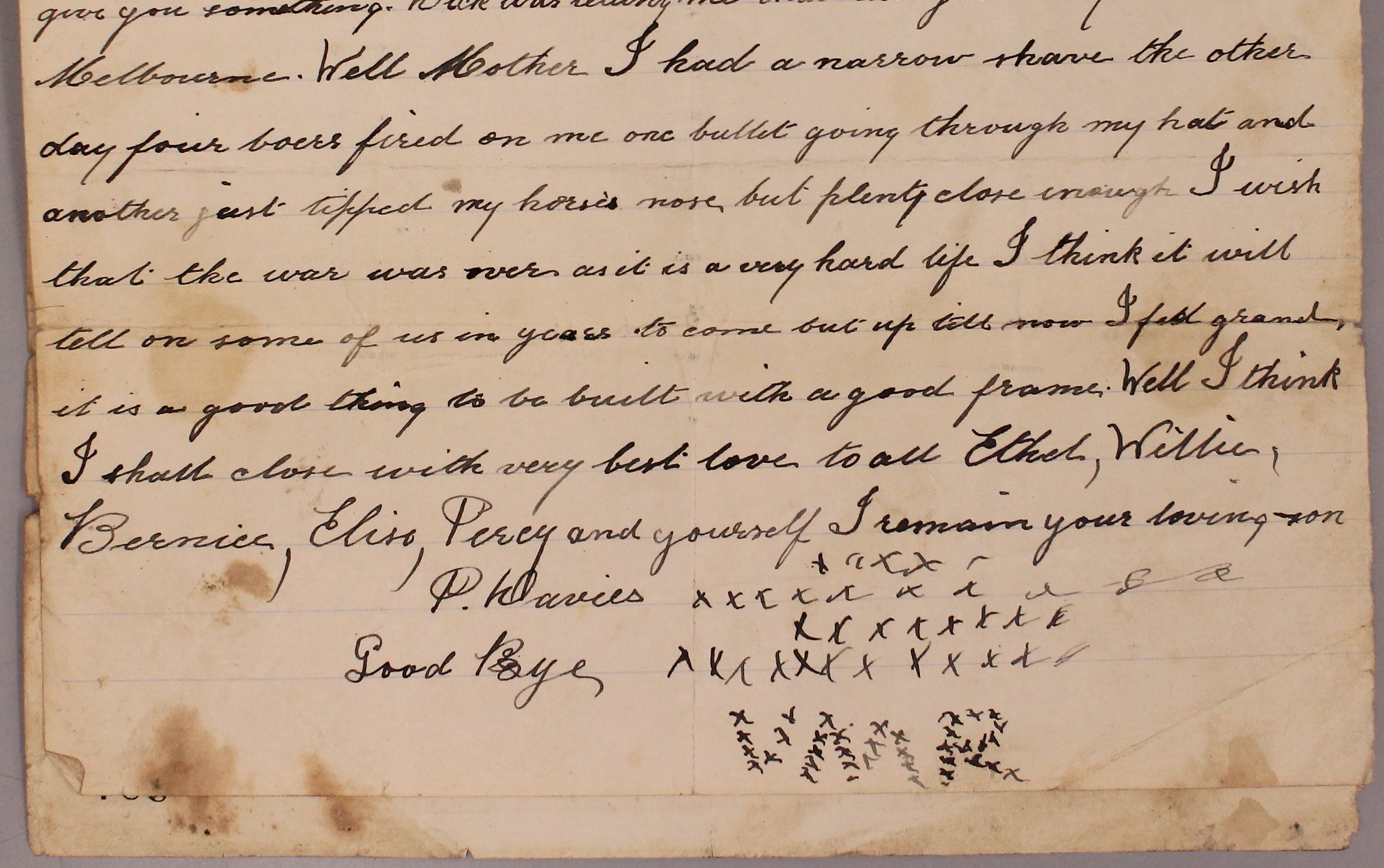

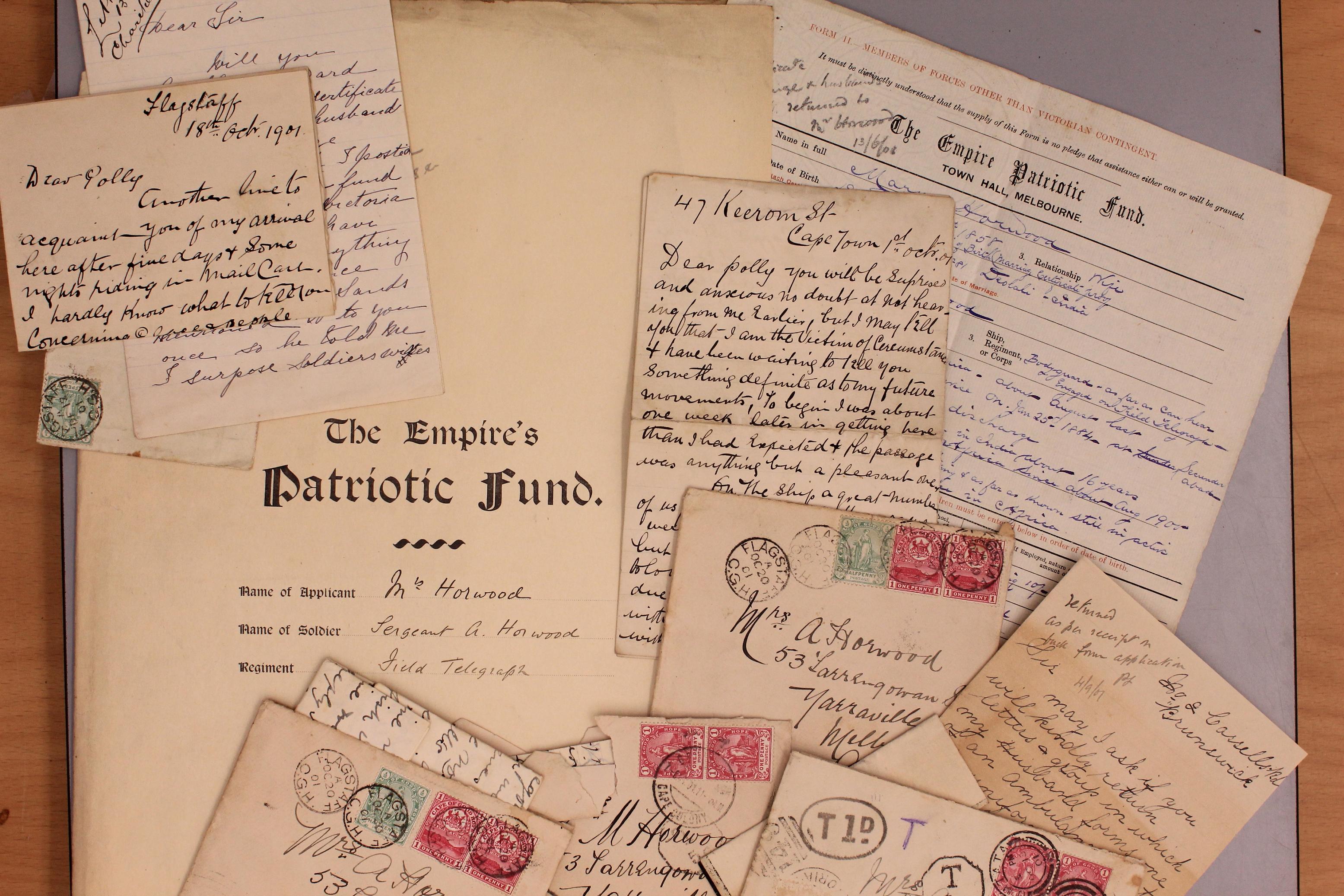

These applications are, essentially, invaluable family history records; through them people can gain an intimate glimpse into an ancestors experience and feelings during a certain time period. Quite often the applications show instances of people having to overcome considerable personal hardships in their lives. The knowledge of this must bring a new perspective of ones ancestors, one that should recognise the great inner strength needed to endure such hardship. Application 141 contained the greatest number of personal letters. Each letter passes on an amazing personal account of life in South Africa, during the Boer war, from a husband, Arthur Horwood, who had avoided the dangers of serving in the British forces and, by luck, found civil employment as a jailer in Capetown. He writes to his wife of his impression on the country, the village where he is working and his hopes to have her travel to him so they can be together. The experiences of the different generations of our families no doubt contributed to the life we now live. Records and memories bridge a gap across time and allow us to understand and appreciate these experiences, this is essential if we want to know where we have come from and what has shaped the history of our families.

The Empire’s Patriotic Fund Application series bring to light the true and unfortunate nature of the Second Boer War, as experienced by Victorians. In South Africa where the fighting was taking place, back home in Australia where many were struggling and then the often difficult aftermath once the war had ended. They focus on a part of history which some may not be aware of. They are important historical pieces but they are also key family history records, giving families the opportunity to connect with the memories and lives of lost relatives.

Fig 8 – Application 141, enclosed personal letters sent by Arthur Horwood, who had found work in South Africa; they are addressed to his wife, Mary. (VPRS 16930/P0, Unit 1)

To read more about the history of Australians in the Boer War, the Australian War Memorial has a great write up, Australia and the Boer War, 1899–1902, on the War history section of their website: http://guides.naa.gov.au/boer-war/

Additionally, the National Archives, Guide 9 The Boer War: Australians and the War in South Africa, 1899–1902, is a comprehensive resource and can be accessed on their website: http://guides.naa.gov.au/boer-war/

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples