Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

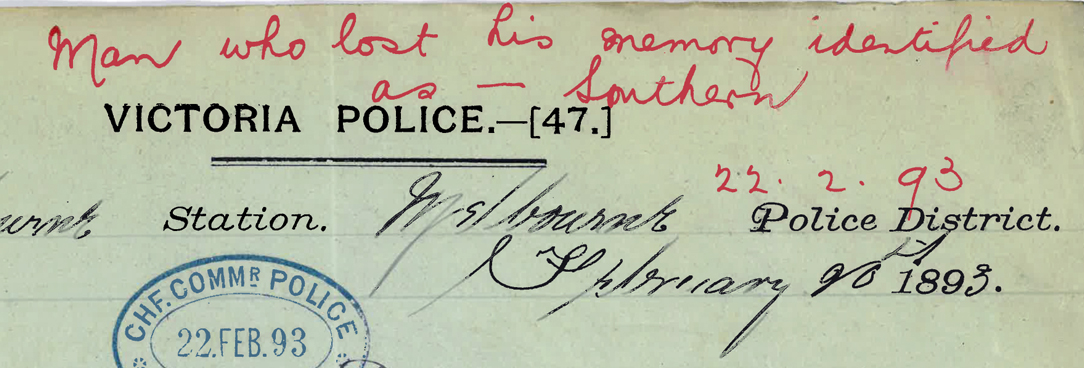

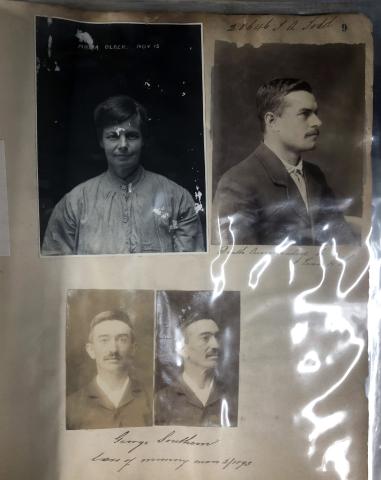

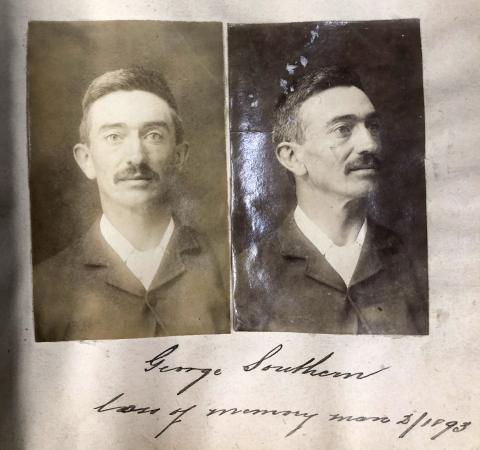

Featured among photographs of prisoners sentenced to death (in VPRS 5900 Photographs of Prisoners Sentenced to Death and Coroner’s Inquest Sheets) is the photo of a wide-eyed man with neatly groomed hair and moustache. His photo is labelled ‘George Southern, loss of memory man 2/1893.’ His photo sits below those of the murderous Maria Black and T.A. Todd of body in the boot box fame. Flip to the next page and you come face to face with Frederick Bailey Deeming. So who is George Southern and why is he included in this record with some of Victoria’s most infamous criminals?

George the traveller

George was an Englishman from Lincolnshire. At 22 years of age George arrived in Australia, settling in Brisbane. He tried working as a pianoforte tuner, but when he struggled in that line of work he began cattle and sheep droving until afflicted with tuberculosis and hospitalised at the Brisbane hospital.

According to The Argus, he became quite a hit amongst the other patients for his musical and story-telling abilities. He would entertain them with mini shows, reciting novels and performing sketch routines. After release from hospital he continued his roving life splitting his time between droving sheep, cooking at stations and tuning pianos. He was known to carry large volumes of books around with him wherever he went and was even published himself in a few English Journals.

After a few years of living a travellers lifestyle, he settled in Wagga Wagga before marrying Mary Steel and moving to Albury. There he worked as both a pianoforte-tuner and insurance man, and his marriage to Mary seemed by most to be a successful one. It wasn’t long before they welcomed a baby girl named Dorothy. But ten months after Dorothy was born, George Southern vanished.

“He did not communicate with his wife, and she thought he had suddenly taken it into his head to go home to his people in England.” The Argus, 22 Feb 1893.

Edward Bellamy

Six weeks later a man awoke one morning under a tree by the beach. According to the words of Dr Shields, reported in the Wagga Wagga Express:

“He did not know himself, nor know where he was, nor had he ever heard of Melbourne. His mind was a perfect blank.”

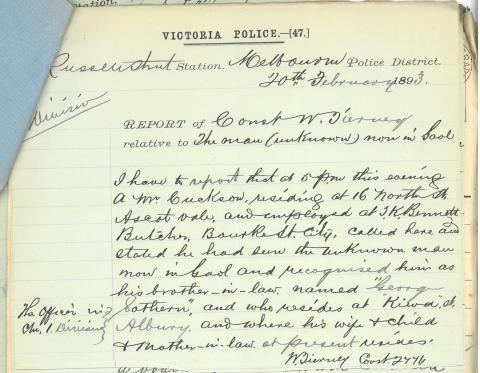

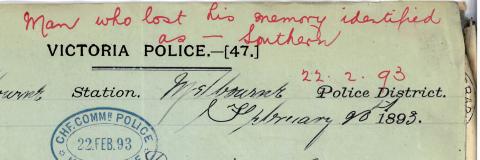

And so, on 9 February 1893 he arrived at a police station in Melbourne asking for help.

“Who am I?”

Unsure what to do with him the courts sent him straight to Melbourne Gaol and the police distributed his photo far and wide, including to mental hospitals, calling for help in identifying the man with no memory. In gaol he took up the name Edward Bellamy until his photo slowly made it into the hands of those who knew him.

Southern apparently said:

“So I'm identified at last, am I? Shall I be taken home now? Shall I see my friends and talk to those who knew me before I found myself by the sea? The prisoners have told me much of home and friends, both of which are words which seem to have meanings I cannot appreciate as fully as they think I should and though I cannot tell why I am really glad I am at last to see my home and my friends. When shall I go there, and what shall I see when I get there? Shall I see walls and men like these around me? Or shall I be able to go where I like without asking permission, and see men round me dressed as I am? The foolish questions, Who are you? What are you? Where do you come from? which people ask unnecessarily, because they should know that if I could answer them I would not be here, will be stopped now, and I shall no longer be called the 'unknown.' They tell me my name is George William Southern. They may be quite right, but I cannot recollect the name. It is not even familiar to me. If it is my name I shall have to take it, I suppose, but I shall be sorry to part with the name of 'Edward Bellamy.' As a name I like it much better than George Southern.” The Argus, 22 Feb 1893.

The return of George Southern

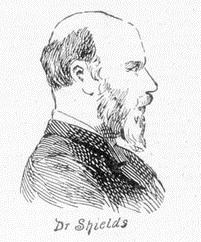

George's wife arrived by the Sydney Express the following day. She said she’d last seen him on the 6th of January and that he appeared to have lost weight since then. He did not recognise her, or his child. By this time, Southern was being seen by the Gaol physician Dr Shields. Mary told Dr Shields that her husband had suffered from headaches in the past as well as sleeplessness, depression and more recently, loss of appetite.

Dr Shields took Southern to a meeting of the Medical Society in Melbourne.

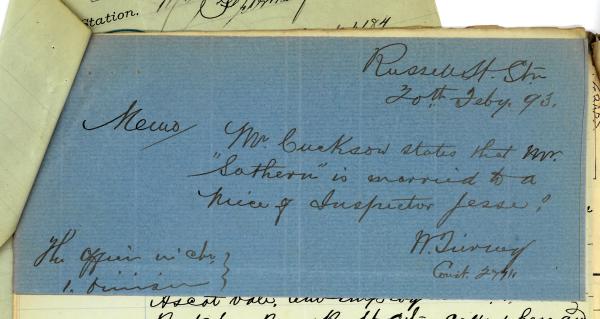

Police correspondence surrounding this visit to the Medical Society can be found within our Police Correspondence files (VPRS 937). The letters describe Southern being escorted by a plain clothes policeman and gaol warder by cab to and from the Gaol to the Society meeting in East Melbourne.

At the meeting, another Doctor, O’ Hara, marvelled at the case:

“This is undoubtedly the most wonderful case of the kind we have ever had in Australia. There is not the shadow of a doubt of its genuineness and when it comes to be diagnosed it will form the general topic of discussion among practitioners.”

Doctors couldn’t agree on the cause of George’s memory loss. And one has to wonder whether Southern was in fact putting his story-telling abilities to use?

It was said in the media:

“Certainly there was no family reason that would cause Southern to desert his wife and child, and then to simulate forgetfulness of the past.” The Argus, 22 Feb 1893.

After George’s identification, more news filtered out through the papers about his missing six weeks.

Apparently between the 6th of January and 9th of February he’d been a boarder at a house in Tasmania where he went by the name Arthur Percival and largely kept to himself. While there he advertised his services to tune pianos and work on colouring portraits.

Interestingly, the police correspondence also reveals that George’s wife Mary was the niece of a police Inspector.

Life after memory loss

Even after returning home, George apparently failed to recognise any of his friends, house or belongings. He did manage to take full advantage of his predicament though, later employed by the Waxworks and Museum to hold reception as The Unknown.

In her 2012 Herald Sun article, Researcher Lee Hooper said that she believed George’s memory loss was all a hoax:

“I think it could be possible that George W Southern might have been in a bit of a desperate place and skipped out on his family that day in January,” Lee wrote.

In Russell Robinson’s accompanying article he revealed that after the whole debacle, George and Mary went onto have four more children and that George died in 1933 at the age of 70. Whether or not George spent all those years pretending he couldn’t remember life before 1893 is unclear.

So… Why is George’s photo included amongst a book of executed and commuted prisoners? It’s hard to know. The record itself seems to be a scrapbook created by the Prisons and Gaols Branch and was most likely a prison-based record held at Melbourne Gaol. It contains no contextual information within it. Along with photos of prisoners sentenced to death, George being an exception, there are also statements by the Governor from inquests into deaths at the prison which leads me to think that the record may have been initially kept by the Governor or perhaps even a prison doctor (Dr Shields?) as a personal file to keep track of death sentences, deaths and, in George’s case, strange medical cases of the gaol. The record would have been moved to Pentridge later on, with copies of photos of prisoners like Jean Lee added at the back. Strangely the record sits within a cover entitled “Register of Officers No.3” yet no register of officers is contained within.

Sources

- Photographs of Prisoners Sentenced to Death and Coroner’s Inquest Sheets, VPRS 5900 P0 Unit 1

- Police Correspondence, VPRS 937 P0 Unit 338, 25 Feb 1893

- The Remarkable Case of Loss of Memory, The Argus, 22 Feb 1893

- The Case of George Southern, The Age, 23 Feb 1893

- The Case of George Southern, Traralgon Record, 28 Feb 1893

- Southern Before the Medical Society, Wagga Wagga Express, 28 Feb 1893

- The Case of George W. Southern, Cootamundra Herald, 1 Mar 1893

- The Case of George Southern, Leader, 4 Mar 1893

- George Southern at Home, The Bendigo Independent, 7 Mar 1893

- The Case of George Southern Under Treatment at Albury, The Herald, 8 Mar 1893

- George Southern at Home, Daily Telegraph, 9 Mar 1893

- George Wm. Southern Supposed to have been in Launceston, The Tasmanian, 11 Mar 1893

- Mr. George Southern Who Has Forgotten His Name, Australian Town and Country Journal, 11 Mar 1893

- The “Loss of Memory” Case, Wagga Wagga Express, 1 Apr 1893

- The Man Without a Memory, Daily Telegraph, 5 Apr 1893

- The “Lost Memory” Man, Bowral Free Press and Berrima District Intelligencer, 12 Apr 1893

- The Waxworks, The Herald, 14 Apr 1893

- The Curious Case of the Memory Man, Herald Sun, Russell Robinson 2012

- George Southern Betted on Life Being Easier Without a Young Family, Herald Sun, Lee Hooper 2012

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples