Author: Dannielle Roberts

Access Services Officer, Ballarat Archives Centre

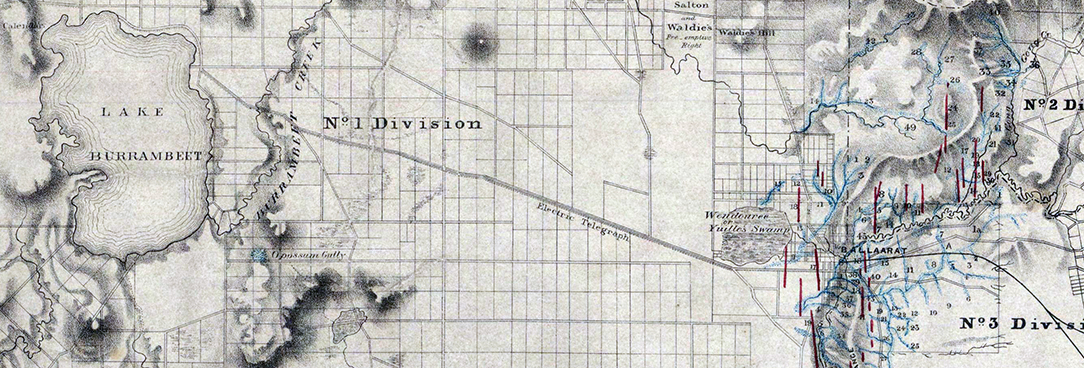

A great mining disaster, mirroring the tragedy that befell the Creswick Mine in 1882, occurred in Cardigan in 1902. In Cardigan Propriety Mine, about four miles from Ballarat, it was feared six miners had drowned and become entombed within the mine.1 For Ballarat Heritage Festival 2024, Dannielle Roberts digs into the Ballarat Archive Centre's inquest files to learn more about this local tragic event from over 120 years ago.

Please note that as this article related to an inquest it may be upsetting for some readers.

In 1895 the Cardigan Propriety Gold Mining Company began works on the site after the area had been deemed a rich avenue for gold bearing lead. In the beginning, the sinking of the main shaft of the mine proved difficult due to the water seepage in the area, resulting in a large pump needing to be installed onsite.2 In 1897 the main shaft was completed, and works could commence on the main drive. But there was always a fear from the miners that the water seeping in could result in a tragedy. Little did they know, this was to come to fruition in 1902.

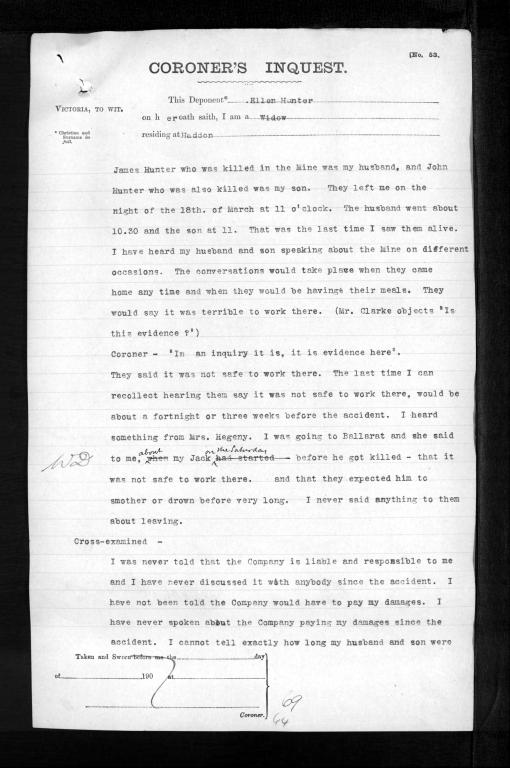

The inquest into the tragedy revealed that conditions within this mine were always questionable. As noted by one of miners' widows, Ellen Hunter:

“They would say it was terrible to work there…The last time I can recollect hearing them say it was not safe to work there, would be about a fortnight or three weeks before the accident. I was going to Ballarat and [Mrs Hegeny] said to me about my Jack on Saturday before he got killed – that it was not safe to work there and that they expected him to smother or drown before long….They were afraid of the water and the ground coming out”.3

Two to three days prior to the disaster, the mine had a case of a burst of sand and water. In the later inquest, the mine inspector mentioned that he was not made aware of this incident and would have inspected the mine urgently and have issued different works for the miners such as not ‘blocking’ in a certain area.4

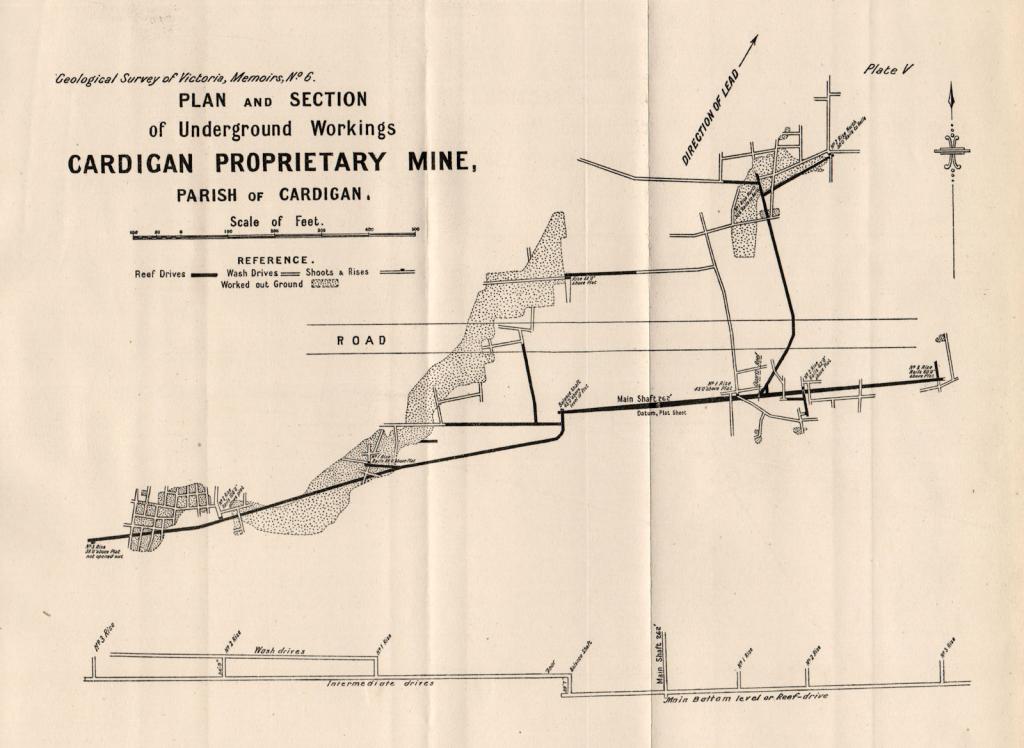

On the day of the tradegy, Tuesday 18th March, 1902, a team of nine miners descended into the mine for their shift. The party consisted of William Mansfield, the captain of the shift, James Hunter and George Simpson and their sons John Hunter and William Simpson, Hunter’s son in law John McGrath and fellow miners John O’Keefe, James Heggarty and William King.5 The men were lowered down the mine shaft via the cage, and proceeded to make their way along the lower drive towards the balance shaft cage to get to the intermediate drive. William Mansfield and James Hunter, John Hunter and John O’Keefe headed up the number 3 rise to the wash drive, digging out the wash dirt. George Simpson, James Heggarty and John McGrath continued working in the number 2 rise, adding supporting timbers while William Simpson and Willie King pushed the trucks along the intermediate drives.6

At 2am, disaster struck with a great wall of water and mud flooding the mine from an unknown underground source. When Andrew Harris, the mine manager arrived at the site, he noticed the pumps had stopped and was informed that the mine had been flooded with several men trapped below.7 John McGrath, who was working in the number 3 rise at the time, recalls what happened that night. He mentioned that himself and George Simpson had been working for one and a half hours, before they dropped a saw to the bottom of the shaft and needed to go down to retrieve it. There, they run into Heggarty who asked to go up and inspect the new rise. With Heggarty only partially up the ladder, a loud sound occurred.

“The noise was just like thunder”8 McGrath recalls. He concluded that a lot of ground was falling and coming down fast. “Come down as quickly as you can”9 John called.

Heggarty and Simpson came down in the darkness as all the candles had been blown out. They headed towards the balance shaft or the main shaft if they were able to get to it. They proceeded another 20-30 feet before they struck the water and sand coming back towards them. The men kept going until they reached number 2. John recalls feeling a body or two along the way. When they got to the balance shaft, they met up with fellow miners King and Simpson Jr. John told the group to continue until they reached the balance shaft and to go down the ladder. John went down first, yelling at the men to follow. The water washed John off at the bottom. He waited to see if any of the other miners had followed. Nobody came. John McGrath continued towards the shaft and proceeded up the cage to the surface and sounded the alarm. The cage was lowered again and up came Heggarty not long later.

George Simpson, still at the top of the ladder believed that McGrath had been washed away. The young boys and Hunter tried to build a barricade to keep the sand and water back. Heading back towards the number 1 shaft, they came across Mansfield’s body and a few feet later, they saw Hunter’s body. The group went back down the balance shaft and stopped there till the water ceased. Later, Simpson wished to go back up the main shaft again but the young boys declined to follow. Leaving them at the balance shaft, Simpson proceeded towards the main shaft and noticed the water was halfway up the pipes. Simpson stooped past them and as quickly as he got past, the cage arrived with Hall and Stride on board for rescue. The two young men, sitting in the balance shaft were later rescued by Mr Fitches and Bowles 48 hours later.

The first bodies to be recovered were William Mansfield and John Hunter, from the intersection of the number 1 shoot where it branched off. The cleaning of the drive continued, and John O’Keefe’s body was found sixty feet east of the number 2 shoot. The mine manager, Andrew Harris noted the bruised and mangled nature of the bodies received, coming to the conclusion that the earth had collapsed and smashed them, being broken up by being washed down or falling down the shoot. If the timbers had fallen down, they would not have come down the shoot. Three months to the day of the accident, the fourth body, the young John Hunter was found lying head downwards in the ladder way, wedged in by the soil.10

A survey of the mine was requested to discover the cause of the sudden tragedy. Surveyor William Baragwanath noted the structure of the mine, with the exception of any new works done. He highlighted the escape measures put in place in case of any hazards such as two drives, escape doors and a balance shaft with the ladder way. In case of a flooding incident, the water would travel down the ladder way and not into the balance shaft. The inquest led to an investigation into previous claims of the mining area and if there were any dangers present prior to the tragedy. There had been no previous danger of water. Andrew Harris thought that recent developments in the mine had caused the tragedy, believing there was a fissure or a tailing out of the rock. The rock therefore becoming weak, while the water was concealed in the rock overhead. Another theory was that there was a channel of water or ground filled with basaltic boulders on the south side of the number shoot, or a basaltic fault.11

References:

1. “Tragedy in a Mine near Ballarat” (1902, March 22). Advocate (page 23) Retrieved from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/169734325

2. Atkinson, J. (2002). The Cardigan Mine Disaster. Jim Crow Press for the Cardigan Centenary Committee, pg. 13

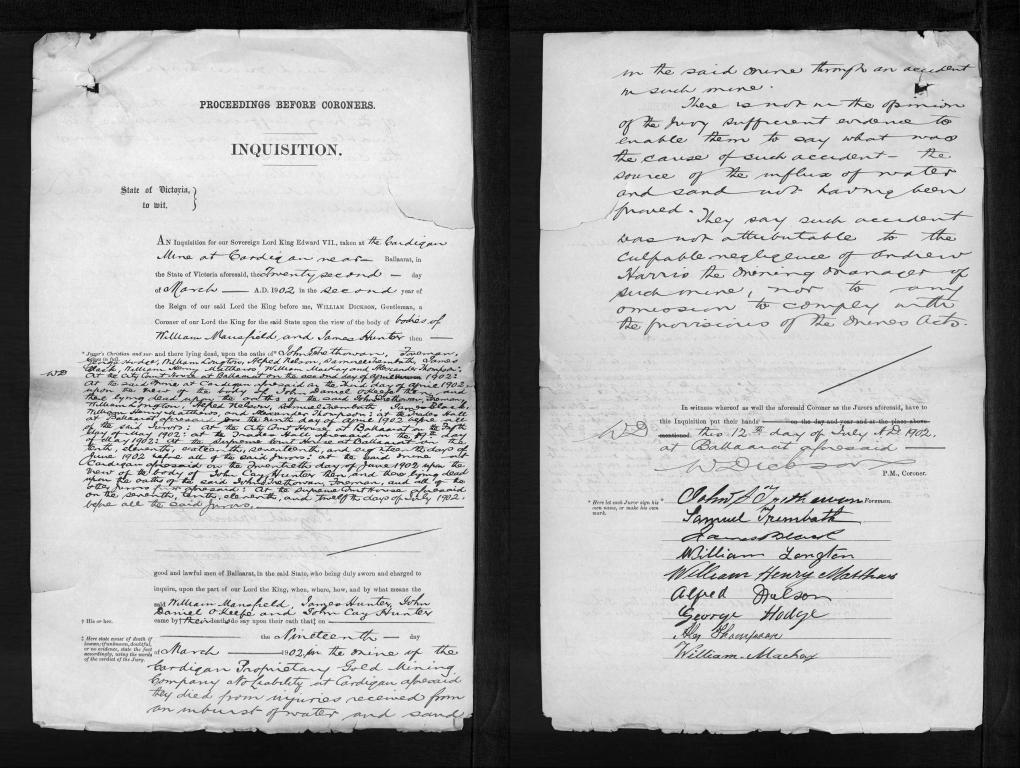

3. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 74, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786 Retrieved from: https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/E9432FF9-F1C0-11E9-AE98-B9DDE7FF7470

4. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 65, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786

5. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 74, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786

6. Atkinson, J. (2002). The Cardigan Mine Disaster. Jim Crow Press for the Cardigan Centenary Committee, pg. 15

7. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 16, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786

8. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 89, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786

9. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 93, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786

10. Atkinson, J. (2002). The Cardigan Mine Disaster. Jim Crow Press for the Cardigan Centenary Committee, pg. 40

11. Inquest file for Williams Mansfield, James Mansfield, John Daniel O’Keefe, John Cay Hunter, pg. 64, dated 18th July 1902: VPRS 24/P0, Item 1902/786

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples