Author: Kate Follington

The Towers of Melbourne

Within the 2018 photography exhibition Beyond Bluestone at the Victorian Archives Centre (now closed and available online here), one of the photos featured was this apartment block in Richmond. The exhibition put on display photos from the State's archival collections about significant public works which transformed Melbourne as a city. Given the scale of these apartment buildings as public housing flats, they were certainly historically significant in both size and need. Almost fifty of these concrete utilitarian buildings are dotted around the inner city, and when they were constructed they marked a major leap forward in Victoria's new policy to provide decent public housing to its poorest residents.

Similarly, anyone catching a tram along the arterial routes in or out of the City will inevitably trundle past large blocks of grass lawn dotted with two or three storey red brick apartment blocks, mostly built between 1950 and 1980 they continue to house low income tenants. It took half a century, and shameful slum conditions, for public housing advocates to be taken seriously in Victoria, but many Melburnians now celebrate living within mixed residential zoning where social housing and gentrification exist side by side.

Housing Commission Victoria

Affordable and subsidised public housing schemes in Victoria were developed and managed, for the most part by The Housing Commission of Victoria from 1938 onwards. Public Record Office Victoria holds significant records from this agency which can help piece together the variety of public housing models they trialed, and why, until they ceased operating in 1983.

To understand why apartment towers, for example, may have been a necessary if not attractive solution it's important to comprehend the housing shortage that Melbourne faced between the major wars and shortly after. The scale of homelessness in mid 20th Century Melbourne is hard to fathom, for example in a 1963 report called The Enemy Within Our Gates: The First 25 Years1 produced by the Housing Commission of Victoria they cited a shortage of housing stock of 80,000 homes. Not only were there thousands of inadequate slum houses identified for demolition in the 1930s but exacerbating the problem was the 1940s war effort freeze on private development and shortage in materials.

Garden City Port Melbourne

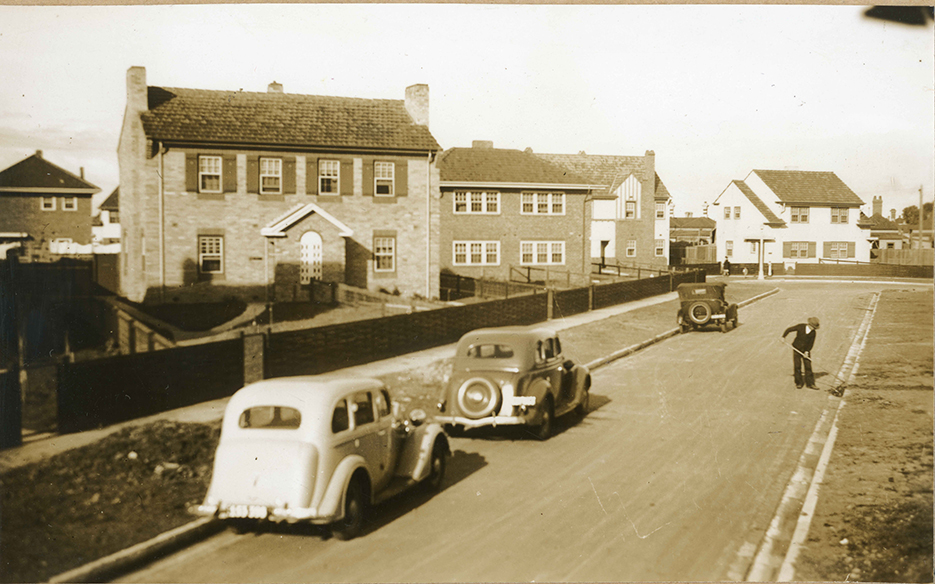

Some of the earliest examples of public housing occurred at Fisherman’s Bend in Port Melbourne with a development modeled on an English urban planning concept called the Garden City Movement. Imaginatively the area was thus named Garden City, and the houses looked more like English country cottages made of concrete than Australian housing: surrounded by hedges and large gardens the model connected streets to corner parks. The housing was built initially by the State Savings Bank, then the Metropolitan Town Planning Commission and eventually the Housing Commission of Victoria in 1936. These black and white photographs of the planning and building of Garden City can be found within the PROV collection in a series of photographs produced by the Public Works Department called Port Melbourne Housing.2 It’s easy to be struck by the disproportionately luxurious size of the blocks given thousands of impoverished families on the northern side of the City in Fitzroy, North Melbourne and Richmond were also desperate.

Oswald Barnett and The Slum Abolition Board

|

|

|

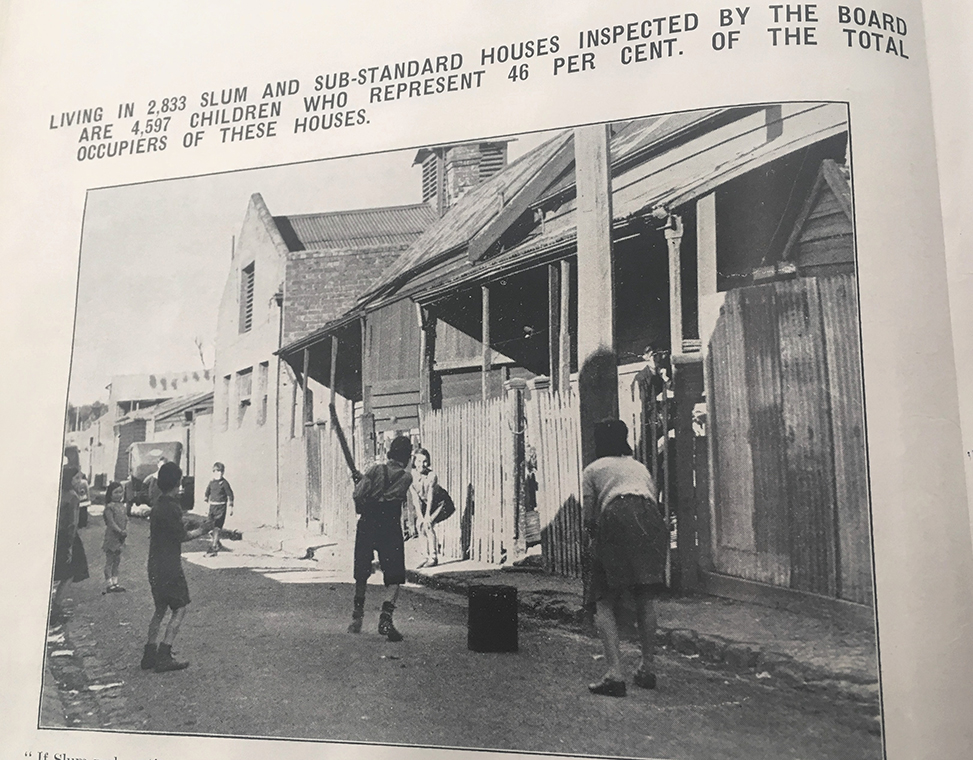

The most dire conditions suffered by Melbourne’s destitute reached a peak around the depression. A poor family’s choice for housing was limited to corrugated tin shacks, back alley sheds, and washing with external taps. Some people even lived on the Dudley 'Bachelor' Flats: the swamps and rubbish dumps along the edge of Port Phillip. Reports at the time from the Sustenance Branch of the Labour Department recorded over 20,000 people were evicted from their homes between 1932 and 1937 due to rental increases.

Melbourne’s ‘slum problem’, and rising child mortality and health concerns attracted the attention of hundreds of social reform groups and was a regular talking point in the newspapers. One of the most vocal critics was photographer and accountant called Frederick Oswald Barnett who regularly drove around Carlton, North Melbourne, and Fitzroy photographing the conditions. His lantern slideshows projected onto walls in theatres and church gatherings were often reported upon and his statistical study of the causes of homelessness made him an admired social reformist.

"…. Mr Barnett said that one estate agent in North Melbourne told him the houses were so few he had a waiting list of 300! The suggestion that if slum dwellers were placed in decent homes they would turn them into pigsties Mr Barnett refuted, stating that every home with a few feet of ground he had inspected had its own garden, 'They only want a chance to get away from their present environment.'" The Age (Melbourne) Sat 20 June 1936 Page 22. Slum Abolition.

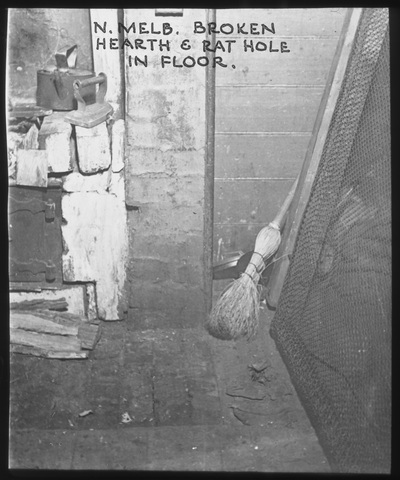

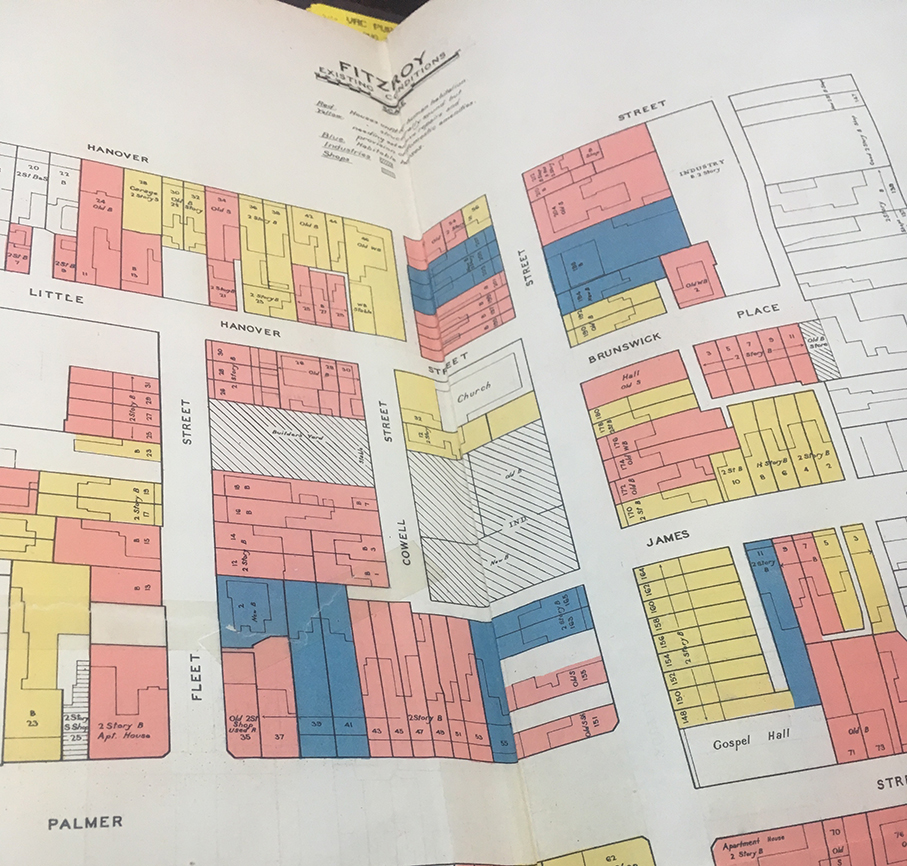

The Slum Reclamation and Abolition Board was appointed by the Government shortly after to identify the worst affected areas within a five mile radius of the City and to propose solutions. Barnett was elected onto the Board and they made some stark observations in their first progress report in 1937. The original report is available to view at Public Record Office Victoria.3

"The board records its horror and amazement at the deplorable conditions under which these thousands of men, women and children are compelled to exist. Hundreds of houses contain small rooms, low and water stained ceilings, damp and decaying walls, leaking roofs and rotten floors. ……a heavy toll is being taken on the health of these occupants, particularly of the women and children." Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board 1937

The report is dotted with photographs of different conditions people were living under as the Board conducted their investigations. It also made a strong statistical case for social housing on the basis that levels of child mortality, juvenile delinquency and infectious diseases were higher in slum areas. They also identified the names of landlords who owned 7300 slums in Collingwood, North Melbourne, Port Melbourne, Carlton, Fitzroy, Richmond and South Melbourne. This caused a considerable stir at the time, as did their ambitious recommendation for the Government to buy back the land and build simple low income housing which would offer employment, and to fund the scheme with scalable rental subsidies as a replacement for other social support system benefits (Page 63). In 1938 The Housing Commission of Victoria4 was created to respond to the report and pursue a mammoth development project to demolish property, build new homes and find a way to fund it.

Unfortunately due to the second world war any large scale solutions proposed by the Board were put on hold until the 1950s, so when efforts resumed 23 years later, not only were the conditions the same but they were more urgent: streams of post-war European immigrants needed homes as well.

Post War Housing Schemes

The Commission went on a global tour to compare post-war social housing efforts in 1958 in Europe, North America and New Zealand and wrote a recommendations report Some Aspects of Housing Overseas by J Gaskin and R Burkitt5 based on a study of public housing programs like New Towns in Britain and Urban Renewal in the United States. Despite multi-storey apartment towers costing more due to the inclusion of lifts, the Commission nonetheless began development on pre-cast concrete towers, similar to the modernist and functional architectural designs being adopted in Europe and the United States influenced by the work of modernist architect Le Corbusier. They also began construction on two-three storey walk-up apartments as well.

"Relating all the above to the Commission’s approach in Melbourne it is suggested that the building cost to the Commission for high multi-storey flats will be higher per flat than for 2 and 3 storey flats, and may be considerably higher." (Page 170 Chapter 11)

Diversity in housing stock

The Commission decided to build around 50 tall apartment towers around the ring of inner Melbourne and although the concrete functional modernist design may have seemed cold from the outside, they were not built without considerable thought for the future occupants health and well-being. The recommendations made in the Commission's 1958 global research report recommended that balconies, playgrounds, childcare, community spaces and gardens were essential. They also insisted that natural light and parking spaces underneath be included in the design. In their 1966 The Enemy Within Our Gates report a review of their efforts reported the towers offered housing to 600 people and that 160 (of the 180) apartments were designed with two or three bedrooms, and that the land management model made available 80% of the land for communal purposes like basketball courts or child care facilities.

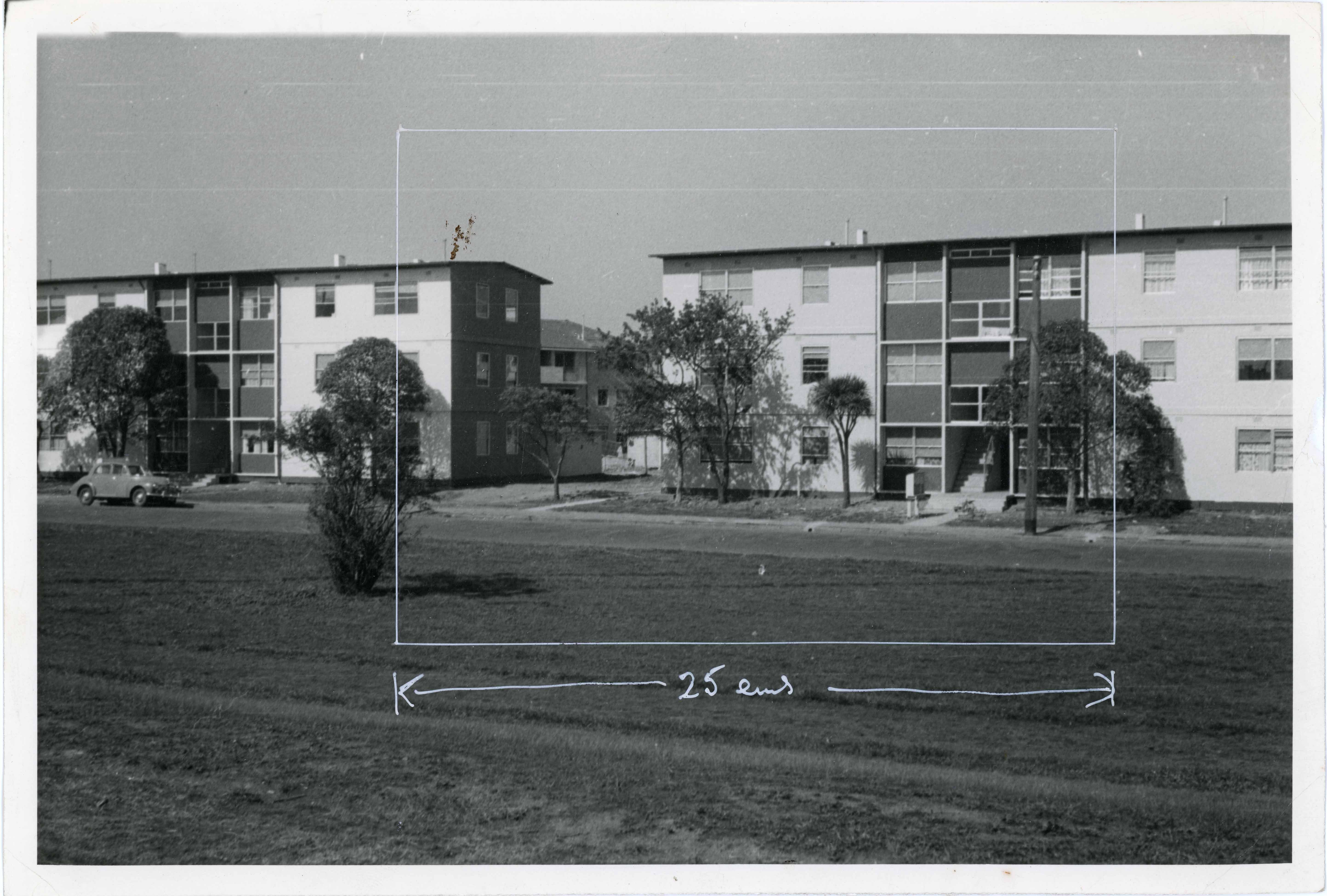

The reaction to the twenty-storey flats as unsightly and too uniform, was offset by plenty of two-three storey apartment developments built within the inner city ring at the same time. A photographic collection of slides6 which capture the variety of dwellings produced by the Housing Commission of Victoria from the late 1940s until the 1980s was donated by a former commissioner to the State Library of Victoria. These slides can be viewed and copies requested in their heritage reading room.

Walk-up apartments like the photographs below of Pigdon Street, Carlton and Dight Street, Collingwood, were a trial of low density social housing development and these designs could cater for up to 30 units per acre. The Housing Commission's clearance rate of property they'd either bought to demolish or to develop, and the pace of the construction of new housing stock from the 1950s and '60s, was extraordinary and not without protest, there's plenty of evidence of this found in newspaper articles on Trove and online about temporary accommodation camps like Royal Park. Annual report data from the Commission recorded 48,000 homes were built or acquired as towers or as walk up flats over two decades.

By the 1970s a different philosophy seemed to take focus, one emphasising individualism, with attractive brochures promoting villas and townhouses in regional Victoria in places like Churchill in the Latrobe Valley. The cost of land acquisition by this time was more difficult in urban areas and was a challenge costing $200,000 an acre, and the only affordable option was a multi-storey dwelling with a view to increased terrace houses into the future.

Funding Model

To fund the decades-long program the Housing Commission relied on selling 50% of the development stock back to families who could pay a 5% cash down payment and manage an interest rate of 4.5%, this was according to their 1967 Annual Report, and impressively by 1980 the Housing Commission of Victoria had completed and purchased 90,227 homes, and sold 49,635 back to tenants.

Sources

1. The Enemy Within Our Gates, Housing Commission Victoria. 1966. State Library Victoria

2. VPRS (Record Series Number) 10516, P3, Unit 20. Public Works Department, Photographs and Negatives of Government Buildings 1926-1965. Port Melbourne Housing Scheme Photos.

3. VPRS (Record Series Number) 8209, P1, Unit 1. Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board, First Report, 1937.

4. VA (Victorian Agency Number) 508, Housing Commission of Victoria 1938 to 1983

5. VPRS (Record Series Number) 8211 P1 Unit 1. Housing Commission Victoria, Report on Some Aspects of Housing Overseas. 1958

6. Collection of Slides, produced by the Housing Commission of Victoria. 1958 - . PCLTSL 113 Box 1-3

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples