Author:

Making it pay

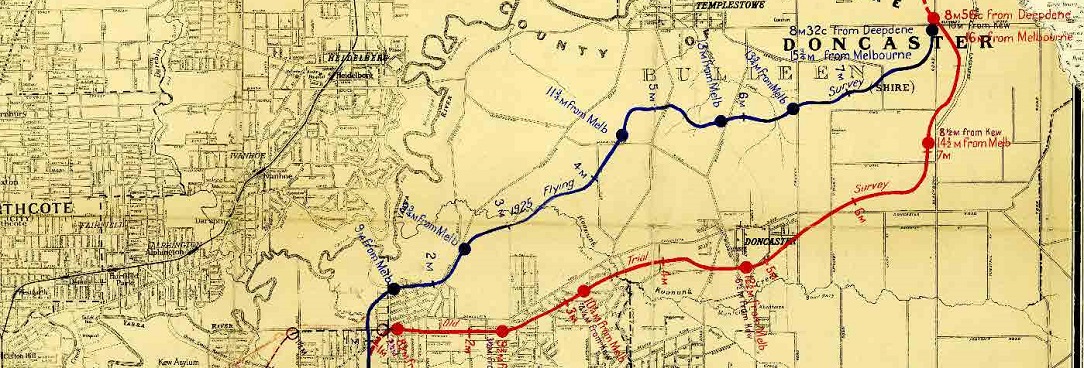

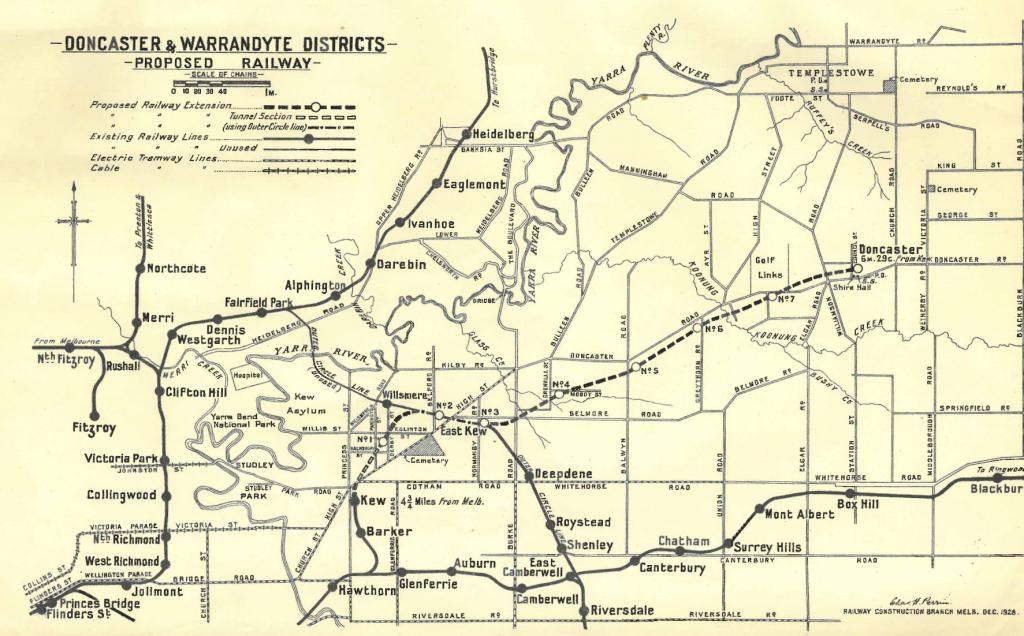

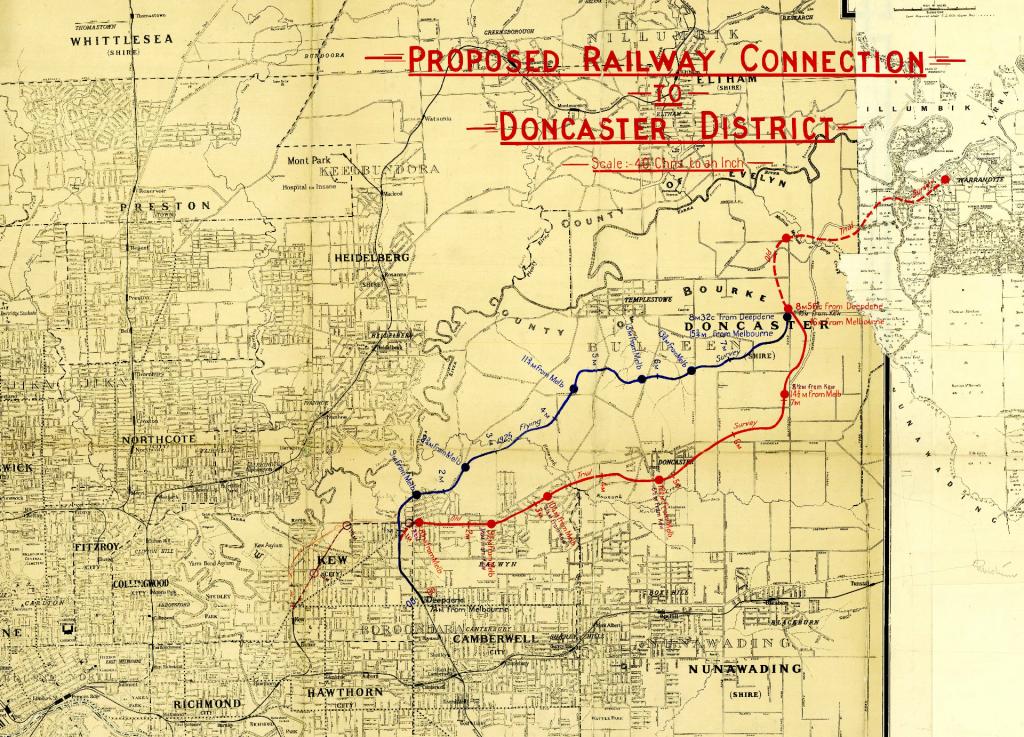

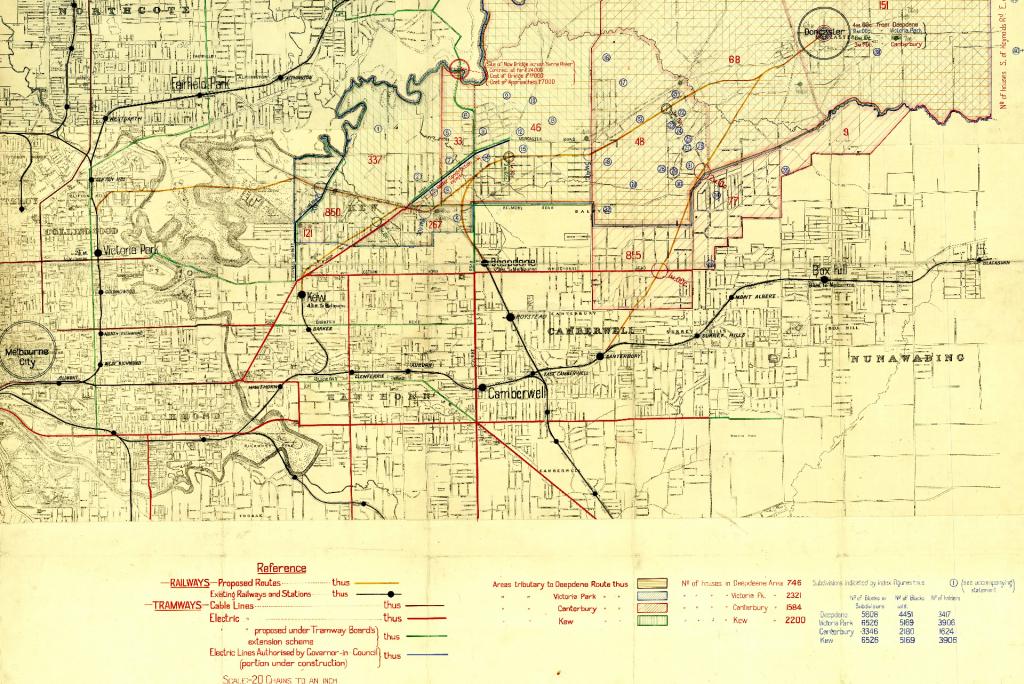

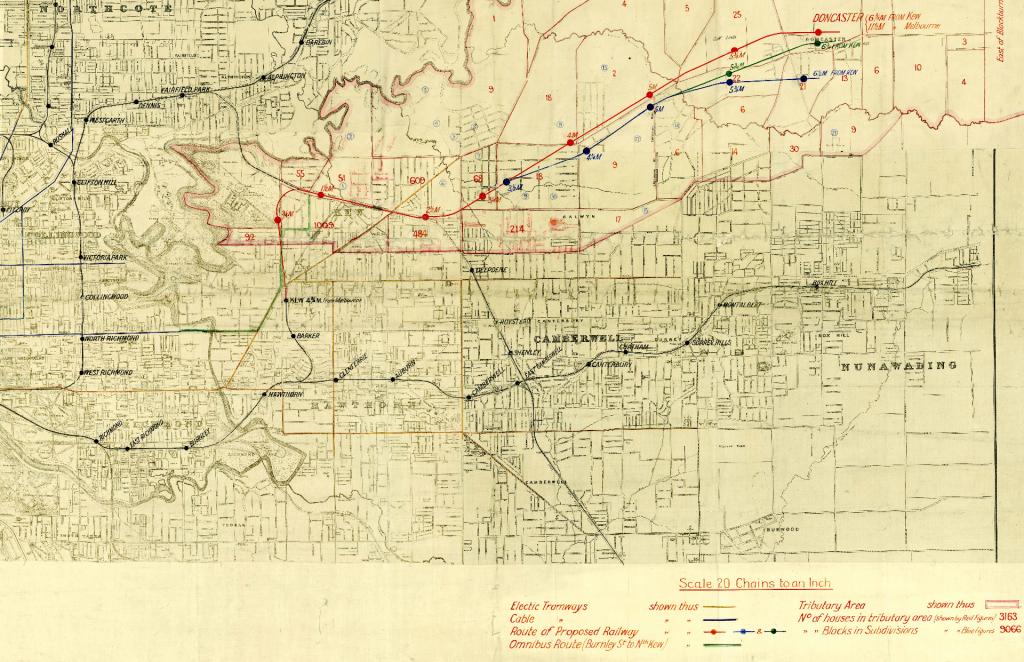

In 1928, a railway line to Doncaster received the endorsement of a key Victorian parliamentary committee. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Railways in its report concluded ‘that it is expedient to construct a railway line from Kew to Doncaster’.[1] A number of similar proposals had been raised at intervals as far back as 1890, beginning with a proposal to build an extension from the existing railway line at Canterbury station.[2] In a report to the Victorian Parliament in 1908, the Railways Standing Committee considered the possibility of a line extending from Victoria Park, through Yarra Bend and the Kew Asylum grounds but concluded that it was not economically viable, and there were not enough residents to justify the financial losses that would be incurred. Another committee report delivered to parliament in July 1925 considered a route from Camberwell station, via East Camberwell and Deepdene to East Doncaster. Again the conclusion was that the economic case was not strong enough and that it was ‘not expedient’ to construct the line at that time.[3] The change of heart only a few years later was partly due to several years of sustained rapid population growth; Melbourne in 1928 was nearing 1 million, nearly double its population in 1900.[4]

The Fitzroy underground

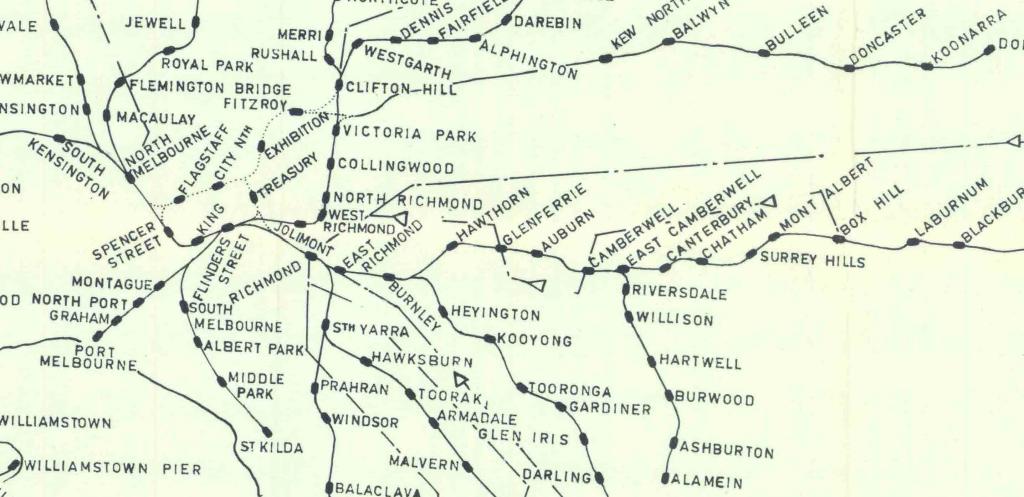

The idea for a railway line to Doncaster has never had a firm and funded commitment for construction. Nevertheless, the idea has refused to disappear and continues to this day to be an aspiration for future network development in Melbourne.[5] The idea was given its most sustained consideration during the 1960s when intensive research was done for a new detailed plan for Melbourne’s transport network that aimed to predict what would be needed to move people around the city by the year 1985. As part of the work done for that plan, a railway line to Doncaster was proposed, either as a branch from the existing Hurstbridge line or along a new freeway route to the east. Extra rail traffic created by the Doncaster line would have diverted just south of Clifton Hill station into an underground tunnel with new stations near the corner of Brunswick Street and Alexandra Parade in Fitzroy and another near the corner of Gertrude and Nicholson Streets, which was to be called Exhibition station. At this stage a number of other railway proposals were also in consideration: a line connecting Dandenong and Frankston directly; a new Rowville line branching from Huntingdale station servicing Monash University and VFL Park and connecting with the Belgrave line at Ferntree Gully station; and a new city station between Flinders Street and Spencer Street stations to be called King (because it would have been located above King Street.

Australia’s first road–rail complex

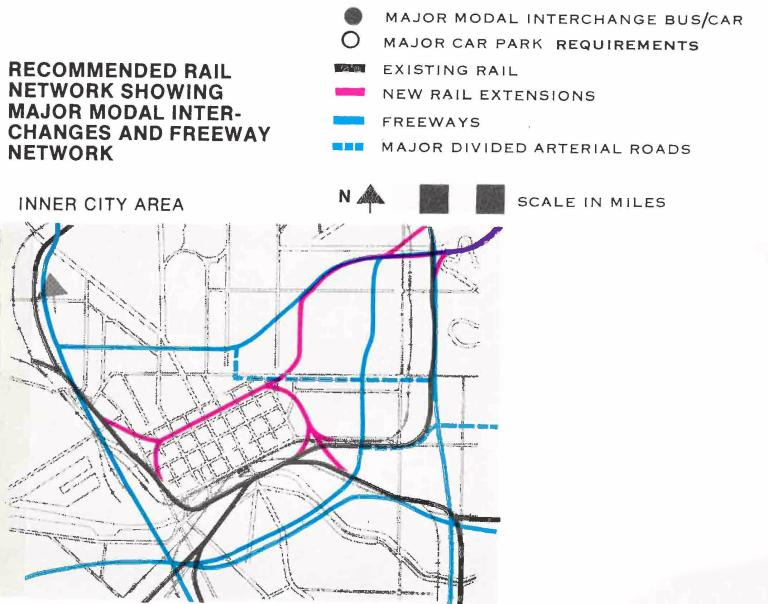

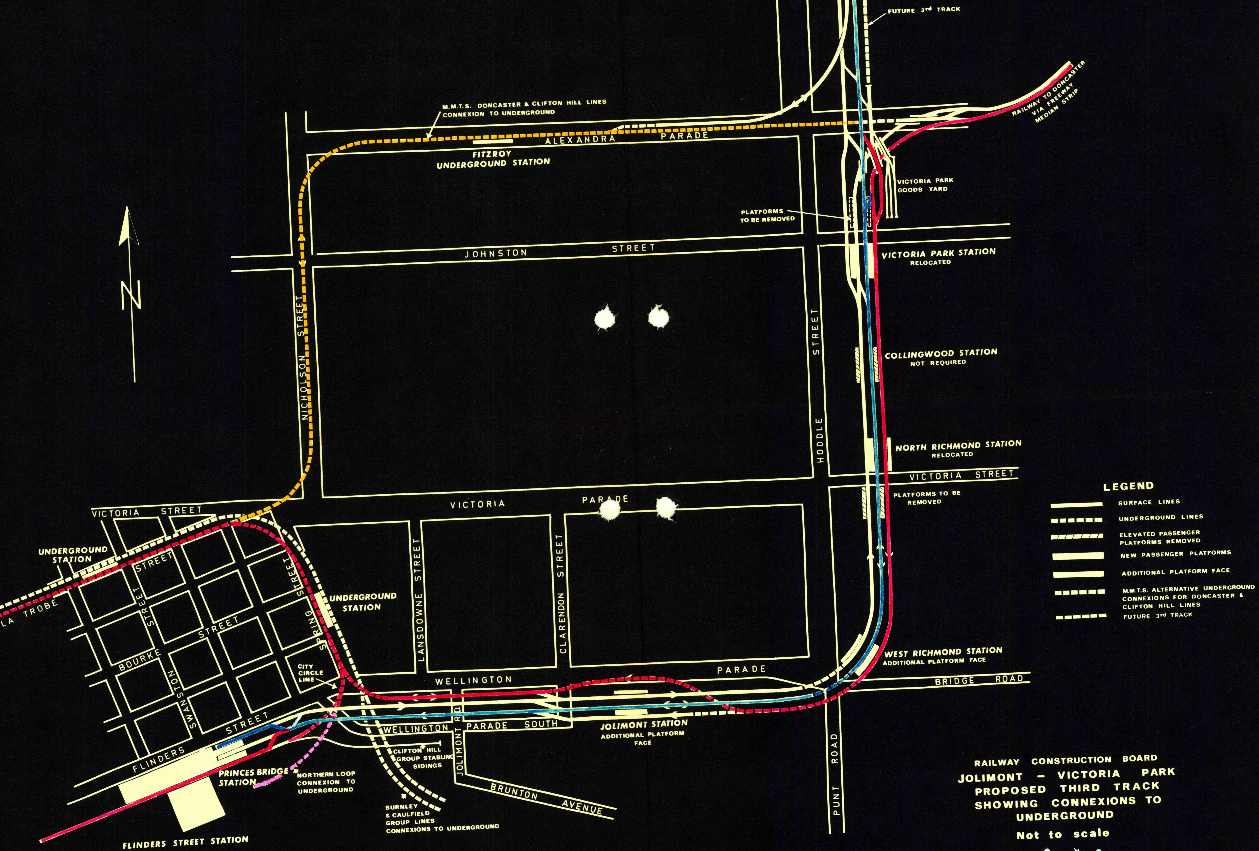

When the ambitious transport plan was finally released in 1969, the railway line to Doncaster was factored into the proposal for the new Eastern Freeway which was designed with a wide median strip to allow for the eventual construction of the Eastern Railway. Promotional materials observed that this would become Australia’s first road–rail complex. At the inner city end, the railway line would burrow underground along with the freeway once it entered Collingwood, in a south-westerly direction toward the central business district. The railway would then separate from the freeway at Nicholson but continue in a tunnel until it reached the city’s new underground rail loop (also part of the 1969 transport plan), with a new Fitzroy station on Alexandra Parade (but without a new station called Exhibition).

When it came time to build the loop in the early 1970s, this plan for a one-way peak hour traffic rail tunnel extending from the loop to the freeway was the first part of the proposed railway to be officially ruled out. The reasoning was that making provision for a junction to the underground loop would be a costly engineering complication, and that a one-way tunnel (inward in the morning, outward in the afternoon) with only one station offered very minimal benefits to commuters and the rail network. In addition, the proposal was originally conceived as part of an underground extension of the Eastern Freeway through Carlton and North Melbourne, with the railway line in the middle until Nicholson Street. And so it was decided that if the Doncaster line was going to be built, all trains would only use the existing tracks through Jolimont, Richmond and Collingwood with a junction just north of Victoria Park station, possibly with the addition of a third set of tracks to deal with increased peak hour traffic to and from the city.

The first stages of the freeway from Collingwood to Bulleen opened in 1977, and the underground loop was completed in 1981, but the Eastern Railway is still waiting for its train to depart.

Searching for transport records

Records about Victorian railways, public transport more generally, as well as roads and bridges, and ports and harbours, can now be searched more easily using our new topic and search pages. These guides allow you to search for transport-related records, including our large road, railways, infrastructure and ports photographic collections, and records relating to employment in the transport sector.

Notes

[1] Victorian Parliamentary Standing Committee on Railways, Report on the proposed Doncaster and Warrandyte Districts Connecting Railway, Legislative Assembly, 13 December 1928, p. 19, in VPRS 438/P0 Miscellaneous Reports, Unit 8.

[2] ‘A railway from Canterbury to Doncaster’, Age, 13 June 1890, p. 6.

[3] Report on the proposed Doncaster and Warrandyte Districts Connecting Railway, p. 1, VPRS 438/P0, Unit 8.

[4] Ibid., p. 18.

[5] As recently as 2013 Public Transport Victoria released a plan that included a rail line to Doncaster, The Network Development Plan, Metropolitan Rail - Overview,

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples