Last updated:

‘Love Is Murder: The fated affair of Frederick Jordan and Minnie Hicks’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Noni Dowling.

The 1890s hit Melbourne with a thud. Gone was the promise and vibrancy of the gold years. Depression loomed. Those who had witnessed Melbourne’s glory in the heady days were now shocked at the despair and stagnation to which the city had so quickly succumbed. Port Melbourne was not immune to these troubles. However, because of the docks’ daily influx of people and goods, employment was still available for some lucky souls. The frequent comings and goings of the port also lent a bustling cosmopolitan air to the surroundings. Like most ports, the area was awash with hotels, dotting the landscape seemingly every few metres, coveting every prime corner position. Many still operate. Of those long closed, the skeletons are still readily discernible in the landscape. The hotels amplified the spirited nature of the burgeoning suburb and were popular not only with locals but sailors too long at sea. Despite the gaiety that these establishments provided, they undoubtedly contributed to the seedier side of life in Port Melbourne. Port itself was a maze of narrow streets, ramshackle buildings and highly questionable street hygiene. Ignoring the lessons learned from Ancient Rome, in an astonishing and dangerous lack of planning Melbourne was without sewerage until 1897. Before then, the infamous nightsoil men lurched through the darkened streets collecting the daily offerings in creaky, leaky carts, dribbling the cargo in their wake. Such fragrant practices led the city to be christened ‘Smellbourne’. In many ways, it was not fit for human habitation. Typhoid, diphtheria, consumption and dysentery flourished in the filth. Despite these mortal dangers, Port in the 1890s would have been a very colourful place to live. Although predominantly working class, all manner of people resided in Port Melbourne — the well to do, down at heel and everyone in between. It was also a popular residence for people straight off the boat. By the 1890s, it appears a small black community had formed in Port Melbourne. Seemingly entirely male, the majority worked at the docks or in other menial labouring jobs. They found themselves popular among the local women, particularly those ‘of a certain class’. In the minutiae of Port life, a loose social group of black men and their white (common law) ‘wives’ evolved. Through the voices found in the archives, their preoccupation appears to have been drinking and swapping partners between one another. It proved to be a volatile mix.

Love is murder[1]

Death comes with a crawl or comes with a pounce,

And whether he’s slow or spry,

It isn’t the fact that you’re dead that counts

But only how did you die?Justin Atholl, Shadows of the gallows[2]

6 July 1894 – The Darkest Hour is Before the Dawn[3]

Down the cobble-stoned lane, the trail of blood stretched the length of two houses. Pickets in a fence, one inch thick, had been snapped in an obvious struggle. Behind them the rickety houses were crammed in, each vying for their own space. The trail continued to a run-down tenement at the far end of the lane. Incongruously, a lady’s hat and boots were neatly placed on the doorstep. On the door above was a bloody handprint. Inside, in the centre of the bed she shared with her lover, lay Minnie Hicks. She was motionless: the death rattle had passed through her body not long ago. Her hands were clasped across her breast. She was still warm to the touch. Constable Kinniburg reeled back in shock, for an instant believing her to be still alive. Once recovered, he took in his surroundings. Blood was everywhere. The walls were splattered, ‘as though squirted from a syringe’, Kinniburg later remarked. The floor was also awash. Someone had made a feeble attempt to clean up the mess by placing carpet over the congealing pools of blood. Above the bed on a nail hung Minnie’s black velvet dress: torn, drenched and muddied. Last night had been stormy. Minnie’s favourite red spotted jacket was also saturated with blood. A pair of moleskin trousers were on the bed; one leg soaking wet from a failed attempt to wash away an obvious bloodstain.

Dr Malcolmson arrived. He calmly took note of his surroundings and pronounced life extinct. Minnie had died only two or three hours earlier, some time in the dawn hours between five and six am. As The Herald stated at the time, the life had been ‘literally pounded out of her’.

Photograph © Noni Dowling 2007.

‘Heard a Siren from the Docks … Dirty Old Town, Dirty Old Town[4]

Minnie had a hard, short life and an even harder, long death. By the time of her demise she was an inveterate drunk. In a previous part of her life, in a union that best exemplifies the notion that opposites attract, Minnie married George Crabtree, a teetotaller. Married in 1888, aged seventeen, Minnie gave birth to little Minnie some time the next year. Settling in St Kilda, the calling of domestic bliss and maternal responsibility went unheeded by Minnie. She hit the bottle. Hard. George would arrive home from labouring to find his Mrs Crabtree passed out on the floor, their infant daughter crawling all over her. Initially, George tried to help his wife. Nothing worked. She began stealing money from his pockets while he slept. Frustrated, George succumbed to his sense of helplessness and rage. He left Minnie splayed on the floor soaking in her own filth while he tended to his daughter.

Minnie fled the marital home, finding work in one of Port Melbourne’s many pawnbrokers’ shops. After eighteen months she returned to George and little Minnie in August 1894. This lasted four weeks. The pull of the bottle was too strong. She turned her back on her young daughter and left for the final time. Minnie reverted to her maiden name, Hicks, and settled in Port Melbourne. Here she found solace among others who displayed a similar commitment to a life of addiction. Like a few other local girls, she also displayed a predilection for the black gentlemen of the neighbourhood. At a time when Catholic and Protestant marriages were considered mixed, this was sure to raise eyebrows and set tongues wagging.[5]

Photograph © Noni Dowling 2007.

6 July 1894 – Attainted: From the Latin attinctus (blackened)[6]

It was 6.10 am. The newspaper boy hollered down the lane. Frederick Jordan got up, fetched a candle from the dressing table, went out and grabbed the paper. He re-entered the bedroom. The light from the candle caught Minnie’s face, bloody and battered. She was dead. He panicked. He roused his housemate, Albert Johnson. The Norwegian was not overly impressed to be dragged out of bed at this ungodly hour. His head throbbed from a long night of participating in his favourite pastimes; carousing and street fighting. What he saw startled him wide-awake. They discussed the matter at length and went to the police.

Jordan arrived at the police station at 7.20 am. He couldn’t restrain himself. He began to cry. Constable Thomas Smith soothed him, ‘What’s the matter, Fred?’ He blurted out, ‘Good God, Minnie’s dead! I woke up and she was dead in our bed’. The Constable reassured him. Jordan continued, the story now tumbling out of him: ‘The last I saw her was around four thirty in the afternoon yesterday. I was on break from work. When I got home she already had drink in her. I left and went back to work at South Wharf. When I got home about eight last night, she wasn’t there. I hit the pubs with Champ and Lee. We started at the Prince Alfred and moved on to the Locomotive. We stayed til closing, around 11.30 pm. I went straight home. Min was still not there so I fell asleep. I woke to find her dead. She was lying on the floor beside the bed so I lifted her onto the bed. There was nothing I could do, life had left the body.’[7]

Constable Smith questioned him as to why it had taken him over an hour to report the death when he lived only five minutes away. Jordan replied that he was scared and unsure of what to do. More police were called in to investigate. It wasn’t long before suspicions arose about Jordan’s account. After some consideration Frederick Jordan was charged with wilful murder and locked up in the cold, bluestone cells at the back of the police station.

Photograph © Noni Dowling 2007.

Born Free

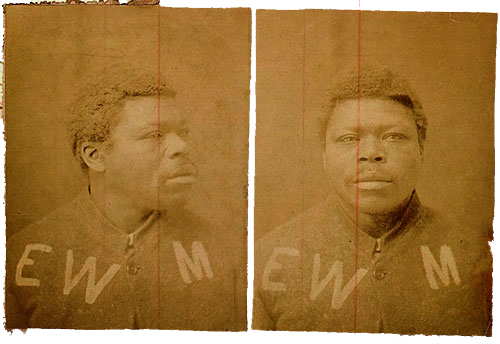

Frederick Jordan was born in Maryland around 1867. He was among the first generation of African-Americans to be born free of the yoke of slavery. His parents were itinerant farm labourers. Leaving the land behind, Jordan headed for the ocean, working on vessels all over the eastern seaboard. At the age of fourteen, Jordan left for Australia aboard The Minion.

Photograph © Noni Dowling 2007.

A number of African-Americans had made their way to Australia by this time. Prior to the abolition of slavery, escaped slaves fled to ports such as Melbourne by disguising their point of departure. After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 abolished slavery, others arrived on free passage.[8] A small black community formed in Port Melbourne. Jordan found work on the docks as a lumper. It was punishing physical work but it made a man strong and muscular. Over time he earned a reputation as a hard, industrious worker.

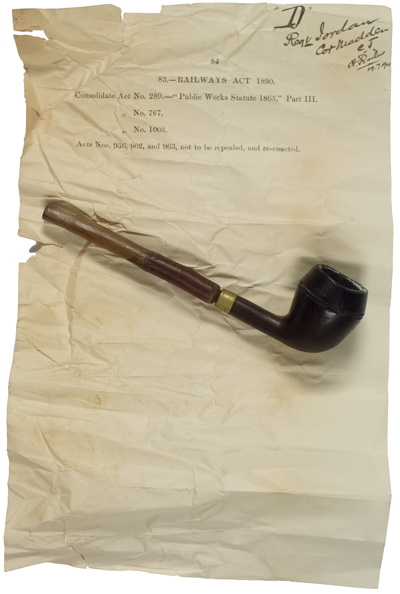

Jordan had two run-ins with the law: one for assault, the second for larceny from the person. He had stolen a watch, chain and pipe from, ironically, a drunk. For this opportunistic sojourn into the criminal world, Jordan spent four months at Her Majesty’s Pleasure.

PROV, VPRS 515/P0 Central Register of Male Prisoners, Unit 48, folio 364.

10 July 1894 – Post-Mortem: What a Fine Mess I’ve Made

George Ardlington Syme performed the autopsy. Hard living had taking its toll on Minnie Hicks/Crabtree. Syme believed her to be thirty; she was in fact around twenty-three. Like most alcoholics she was also undernourished. The slight, pale body was clothed in underwear — a chemise and petticoat, no nightdress. Her face was covered in bruises: two black eyes and a broken nose. Seventeen bruises were found on her left arm, as if she had been forcefully grabbed. There were more on her right arm; defensive wounds. Old scars were found near her right groin and right eye. There was evidence of a past lung infection. On the right side of Minnie’s head the scalp had been torn away. Under this, part of her skull was dislocated and blood had clotted. There were further bruises on her neck. She had also been strangled. More bruises were behind each ear, caused by direct blows. The blood from the nose had caused the excessive amount of blood at the scene. Minnie Hicks was beaten to death. Syme found that she had died from bleeding into the brain caused by external violence.

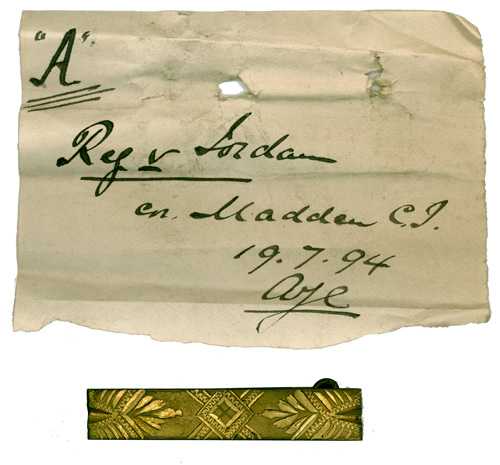

5 July 1894 – Girls’ Night Out

Minnie had spent the whole day cleaning. She became sick of it. She had been slipping into her room intermittently all day to slug from a bottle of grog hidden there.[9] Albert Johnson gave her five shillings to buy some provisions as Frederick Jordan no longer trusted her with money. She bought a forequarter of mutton and put it into the fire to cook. She pocketed the remaining four shillings, enough money to ‘go a long way where immense draughts might be procured for threepence each’.[10] She returned to her room to get dressed up. She brushed her strawberry blond hair. Then she put on her black velvet dress and her favourite red spotted jacket. She clasped her gold brooch just above her bosom, laced her boots and grabbed her hat. She was ready to face the night.

As she walked, clouds gathered overhead, threatening rain. A wild wind blew. She held onto her hat to keep it from flying away. Windy days were a problem in the Port. Depending on the direction of the wind, one might inhale the stench of the abbatoir, the eternally ripe lagoon, or Swallow and Ariel’s biscuit factory — pleasant on chocolate days, not so pleasant when doggie biscuits were baking.[11]

At The Rose and Crown, Minnie met her good mate Rose Lorn, whose interests in liquor and black men mirrored her own. Their marathon effort then moved on to the All England XI where they both drank two three-pennorths of beer, a large serve. Fortified with Dutch courage, Minnie decided to visit her former beau Harry Adams, a black man. At one point, she had left Jordan and shacked up with Adams. During this time Rose moved in with Jordan. It was an incestuous group. Jordan, however, did not like to share and made numerous attempts to win Minnie back. After a couple of months, Minnie meekly returned to Jordan. Perhaps accepting it as part of life or a matter of survival in tough times, the to-ing and fro-ing did not seem to affect the friendship between the two women.

Photograph © Noni Dowling 2007.

When they arrived at Adams’, a quarrel broke out with his ‘wife’, Emma Harris. Trying to avert trouble, Adams gently yet firmly pushed both out the door. In response to this perceived insult from her former paramour, Minnie smashed their windows.[12]

To steady themselves Minnie and Rose moved onto The Locomotive. Here they downed a couple of ‘shandygaffs’, a mix of beer and lemonade. The drink making her tongue loose, Minnie confided to Rose that she was too scared to go home. Rose was not surprised; she had seen the marks. It was decided Minnie would stay with Rose that night.

When they arrived at the house Rose shared with her ‘husband’, Charles Champ, there was no light on. With no key, they decided to seek shelter at Charlie Turnball’s in Ingles Street, 100 yards away. Turnball, a black man, and his ‘wife’ Christina Reid, were in bed when Minnie and Rose banged loudly on their door. As Rose stated, by this stage they ‘had been all the way round Port Melbourne and were pretty well screwed’. They arrived bearing gifts of more drink. Polishing that lot off, Turnball went to buy more. The girls talked. Minnie was petrified of going home in her state. She confided that she had spent all her money and pawned all her clothes. She laid her head on Christina’s shoulder and said, ‘I am going to get beat’. Charlie returned with more ale. This was to be the final nail in the coffin for Minnie; ‘the finishing drink’ as Turnball eloquently described it. Rose and Christina left to gather bedclothes from Rose’s house.

Here someone waited for them: Fredrick Jordan. He had been drinking solidly all night with Charlie Champ and David Lee, another man Minnie was rumoured to have had a fling with. Jordan was obviously agitated. ‘Where’s Minnie?’ he demanded of Rose. ‘You do know, if you tell me I’ll give you five shillings.’ Rose bravely stood her ground. She would not betray her friend. ‘I won’t tell if you give me gold, I know you will beat her.’

Christina scurried past, racing to get back to the safety of Turnball. Menacingly, Jordan followed. On Turnball’s doorstep he spied Minnie’s hat and boots. He stormed into the front room where Minnie was lying on the floor. He berated her, ‘You are spending my money with other women. Get up you damned drunken bitch!’ Minnie timidly replied, ‘I’ll go home if you don’t beat me Fred. I can’t get up Fred’. In response to this plea for mercy, Jordan savagely pulled her up by the hair, tearing chunks of hair from her scalp. He smashed her head into the wall and viciously dragged her across the floor. He then kicked her in the ribs. Turnball tried to obstruct him, but the enraged Jordan pushed him to the ground. Charles Turnball implored, ‘Leave her alone! Don’t murder her in my place take her out!’ Jordan snarled, ‘Leave me alone. I’ll finish her now, I know what I’m doing’. He obeyed Turnball’s plea not to be involved. His role after all was to provide a bed for the night, not to offer protection. Frederick Jordan grabbed Minnie by the wrist, and put his other hand over her mouth to stop her from screaming. Between his fingers, her blood oozed out. He forcefully shoved Minnie out the door, picking up her hat and boots on the way.

Things that Go Bump in the Night

Jordan dragged Minnie into the wild night. The oppressive sky added an aura of melodrama to an already intense evening. The air was electric. Between sporadic thunder and lightning, many Port Melbourne residents heard ominous sounds that night. Charles Champ heard the pair in Bay Street, Minnie yelling, ‘I will not go home to be killed!’ As they neared home around 1.20 am, Mary Ellen Chifney, who lived on the corner of Sydney Place, was alarmed and scared. The noise she heard was like a drunk being dragged along the rocky lane. A man’s voice boomed, ‘Get home with you’. Then came the sound of someone tumbling violently against a door or fence. A distressed woman’s voice uttered ‘Oh, oh, oh’. To Chifney, it was a sound of someone ‘very nearly finished’. Before she could hear any more, the strong wind blew away the terrifying sounds. She dearly wished her husband was at home and not out at sea in the Navy.

James Gray, Jordan’s neighbour, also heard the drunken pair. ‘Where did you get it? Where did you get it? Where did you get it?’ a man harshly bellowed, as if towering over someone. Gray was certain it was Jordan; he was familiar with his gruff voice. The Town Hall clock struck two. Unperturbed, Gray drifted back to sleep.

10 July 1894 – The Inquest: from Victim to Depraved Wretch

Jordan’s story to the police, that he had not seen Minnie that fateful night, crumbled as soon as Turnball produced Jordan’s pipe, Minnie’s gold brooch and a clump of Minnie’s hair torn from her head, all of which were retrieved from Turnball’s house. To counter this setback, the defence lawyer, Mr Emerson, went about the time-honoured tradition of denigrating the female victim. Unfortunately, Minnie had given him plenty of ammunition.

PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 984, Case number 364/1894.

Rose Lorn testified that when she heard Jordan say he would kill Minnie, she thought little of it because it was an expression she heard frequently. To this, Emerson replied that such threats to kill were ‘a “by-conversation” among the people down her way’. This perception was further reinforced when Charlie Champ testified he had not beaten his wife, lately. Emerson inquired if Minnie ‘had the run of all you dark fellows down there’.

Christina Reid’s testimony continued to paint a salubrious picture of life in Port Melbourne:

I have seen men knocking women about. There is a great deal of quarrelling with these black men and their women; they make free with one another’s women. ‘Get up you dirty drunken bitch’, I have heard that expression many times before…

After these lurid details came out in the press, Emerson became public enemy number one in Port Melbourne. The local paper, The Standard, was irate for weeks over the pall he had thrown over ‘the sublime and cheerful picture of moral life in our model town’.[13] The ‘decent’ women of Port were not pleased. It was suggested Emerson buy a pair of boxing gloves to defend himself from them. Apparently, they wanted to lynch him. In response, Emerson wrote a letter to the paper reassuring the women of Port Melbourne that his remarks ‘referred only to women like Hicks’.[14]

19-20 July 1894 – Trial : Watch me Pull a Rabbit out of my Hat

With little else to work with, Emerson created a defence that Minnie had caused her own death by falling over drunk. He badgered the medical practitioners, Malcolmson and Syme, for any evidence that might even vaguely support this theory. While both admitted a number of bruises could have been caused by a drunken fall, all of the bruises could not have been. Neither was willing to concede that the fatal blow could have been caused by a drunken stumble.

PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 984, Case number 364/1894.

Unwilling to give up, Emerson argued that for first-degree murder, there must be a motive. In this instance there was none, for it was ‘the ambition of every black man’s life to live with a white woman’. The jury didn’t buy it. They retired at 12.59 and returned at 3.45 pm with a guilty verdict. The death sentence was passed. ‘I have not received justice here’, Jordan yelled from the dock as he was led away.

The Last Resort of the Damned

Emerson wrote a petition to persuade the Governor to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. For this he used every trick in the book. First he played the race card, stating Jordan’s Negro blood made him ‘too passionate and animal like to control his intellectual faculties’. Next out of the deck was the class card. Men of his social stature (or lack thereof) were widely known to become extremely jealous and ill-tempered, particularly after drink. Rather, Jordan’s actions were influenced by ‘extreme provocation and (he had) acted under the impulses of a frenzied mind unaccompanied by reason’ — two defences conflated into one. These arguments convinced a number of people to call for leniency. The petition attracted one hundred and eleven signatures including Members of Parliament, the foreman of the jury and some ‘very influential gentlemen’.

His Excellency the Governor, The Right Honorable John Adrian Louis, Earl of Hopetoun GC MG, did not concur. The royal prerogative of mercy was denied in this instance. The execution date was set for 20 August 1894.

‘If it Hadn’t Been for Whiskey, I’d be Free as any Bird to Fly Away’[15]

After the trial Jordan was transferred to the condemned man’s cell that adjoined the execution chamber in Old Melbourne Gaol. Like all good lapsed Catholics, once confronted with his mortality, Jordan re-acquainted himself with his faith. The prison chaplain, Father Walshe, gently coaxed him along. Slowly, his fearful demeanour gave way to a calm air. He wrote a letter distancing himself from his protestations of innocence. The more he considered the case, the more he was convinced he had committed a foul crime. It was, however, ‘too late to say I am sorry’.[16]

The dreaded day arrived. It had been only forty-seven days since Hicks was found dead. Even the newspapers commented on how swiftly the wheels of justice had turned in this case. It seems likely that race played a large part in the justice system’s efficiency. The crime of a black man murdering a white woman was one of the most heinous imaginable. It deserved swift, harsh punishment.

While a crowd of between two and three hundred people gathered outside the gaol gates, Jordan took communion. Sheriff Ellis entered his cell with Roberts, the hangman, and his assistant. They pinioned the prisoner. The Sheriff led the way to the scaffold. The Herald reported that Jordan strode purposefully, standing ‘erect and steady when he arrived in full view of the small party of spectators assembled in the shadows of the gallows’.[17] He stood on the spot marked by white chalk and kissed the crucifix proffered him by the priest. A reporter present exclaimed:

…what a change was there from the furious being, mad with drink, in whom all the fiends of hell seemed to rage on that terrible morning when he hammered the poor remnant of a misspent life out of the body of his wretched partner.[18]

The hempen collar was placed around his neck. He twitched involuntarily. The hood was placed over his head; forever shutting out the light of the world he was leaving and shielding those below from the gruesome reality of death by hanging. Asked for any last words, he replied, ‘I have nothing to say; it’s no use saying anything’. The sheriff signalled, Roberts pulled the lever, the trapdoor opened and Jordan plunged through. The measurements that Roberts had troubled himself over were spot on: death was instantaneous. As was customary, Frederick Jordan, 27 years of age, dangled from the gallows for one hour.

‘Booze to Blame’[19]

The evidence against Jordan was more than compelling. The neighbour’s testimony explained the broken fence and the bloody handprint on the door. Jordan carried Minnie’s hat and boots home; he placed them eerily on the doorstep. What remains a mystery, however, is what Jordan was referring to when he bellowed aggressively three times, ‘Where did you get it?’ Minnie said she was broke; but Jordan may have had money in mind. She may have received this by pawning her clothes. However, it is possible Jordan jumped to the conclusion that Minnie was prostituting herself, as some women did to survive during this tough time.[20] Enraged and fired up on liquor, Jordan delivered the fatal blow. A muscular, solidly built man was no match for a woman wasted away by years of chronic alcohol abuse. Minnie probably fell to the floor unconscious. Dying slowly, she eventually succumbed to her injuries just before dawn. Jordan passed out on the bed, awaking with little memory of the night before. He lifted Minnie onto the centre of the bed and clasped her hands together; an act a Roman Catholic would perform. He made a feeble attempt to cover up the messy death, but realising it was useless, thought his best chance was to go to the police and spin a story.

It very nearly worked. Speaking after the execution, the foreman of the jury, Donald Brown, stated that since the trial he had visited Sydney Place where the murder took place. He found it to be lined with bluestone pitchers. He told The Herald that this made it much more likely that Minnie Hicks had fatally injured herself in a drunken fall. Had this information been made available to the jury, he believed a verdict of manslaughter was likely.

As Emerson, the resourceful defence lawyer, told The Standard, ‘Jordan and Hicks lived a wild kind of life, in a neighbourhood where there was so much drinking going on. In Port, women received hard knocks and were used to it’. Although the poem ‘Shadows of the Gallows’ emphasises the manner of death, here the hard, desperate lifestyle which comes with any form of addiction proved to be fatal for both parties. The newspapers lapped up the sordid nature of the crime. Poor Minnie received no sympathy in the press; she was a ‘wretched drunkard of intemperate nature’. The general consensus was that she got what she deserved; after all she did take ‘coloured’ lovers and drank far too much for a lady.

It was the ‘demon drink’ that bound these two young lovers together. Their lives revolved around drink, reading like a soap opera, a melodrama played out in and around the pubs of Port Melbourne. The area provided many venues for those with the same penchant; a ready-made social network for strugglers with a thirst. Port thrived on booze.[21] That fateful night, Frederick’s love of the bottle overtook everything. Obviously a violent man by nature, alcohol made it easier for him to surrender to a lust for power, so easily found in the cries for mercy from a defenceless woman. Whereas previously he had only injured her, this time he managed to kill his ‘paramour’. Minnie may have been far from an angel (it is only natural to ask ‘what sort of woman would abandon her child for the drink?’) but she certainly did not deserve the fate meted out to her, particularly at the hands of a man whom, presumably, she had once trusted.

Perhaps Frederick Jordan didn’t deserve his gruesome death either. In today’s world, a barrister would no doubt argue that alcohol was a mitigating factor, lessening Jordan’s responsibility. It is possible he would be charged with manslaughter rather than murder. In the 1890s, however, such factors were not taken into account. Punishment was swift and severe. It was not long after the commission of the crime that Jordan’s muscular body was dangling from the end of a rope. The drink that these two souls thrived on, imbibed together and which probably brought them together in the first instance, became their undoing. As in so many cases, then and now, the case of Frederick Jordan and Minnie Hicks was a domestic matter that quickly got out of control because of the amount and frequency of alcohol consumed over time. All things considered, it appears to be a case of ‘the booze to blame’.

Endnotes

[1] Ian Rilen, Love is murder, Phantom Records, 2000.

[2] J Atholl, Shadows of the gallows, John Long Ltd, London, 1954.

[3] All factual material used in this article has been gained through research at PROV. Information relating to this case can be found in the following archival sources: VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 791, Melbourne General Sessions, Case number 48 of February 1890 (Jordan’s larceny case), and Unit 984, Case number 364/1894 (Jordan’s murder case); VPRS 264/P0 Capital Case Files Trials, Unit 23, Frederick Jordan; VPRS 1100/P0 Capital Sentences Files, Unit 2, Frederick Jordan. Except where noted all quotations have been taken verbatim from these sources.

[4] The Pogues, ‘Dirty Old Town’, Rum, sodomy and the lash, WEA Records, Stiff Records, 1985.

[5] N U’Ren and N Turnball, A history of Port Melbourne, Oxford University Press, Sydney, 1983.

[6] A legal term used to describe a condemned prisoner awaiting death. In this case the protagonist was ‘blackened’ long before his death sentence was carried out. He was African-American.

[7] This is not a verbatim account of Jordan’s conversation with Constable Smith. A conversation took place between them that included all the information given.

[8] O Ruhen, Port of Melbourne 1835-1976, Carrell, Melbourne, p. 137.

[9] There is no direct evidence of this in the transcripts. However, Jordan referred to Minnie as ‘jolly’ when he saw her at 4.30 pm. She also drank the same amount as Rose Lorn but was significantly more affected. It is possible to infer that Minnie had been discreetly drinking throughout the day while on her own.

[10] The Standard, 21 July 1894, p. 3.

[11] Pat Grainger (ed.), ‘They can carry me out’: memories of Port Melbourne, Vintage Port: Worth Preserving Project, Port Melbourne, 1991, p. 16.

[12] This appears to have been a popular pastime in Port Melbourne. When Jordan went to retrieve Minnie, he smashed Adams’ windows. The local paper, The Standard, also reports numerous instances, including one on 19 July 1894 when four men were arrested for smashing windows at the All England XI hotel. It was possibly a popular way to exact revenge, for presumably windows would have been an expensive item to replace during the Depression. It was hitting them where it hurt — the hip pocket.

[13] The Standard, 14 July 1894, p. 2.

[14] ibid., 28 July 1894, p. 3.

[15] Tex Perkins, Don Walker and Charlie Owen, ‘Fateful Day’ from the CD Sad but true, Polydor, 1993.

[16] Herald, 20 July 1894, p. 1.

[17] Argus, 20 July 1894, p. 1.

[18] Herald, 20 July 1894, p. 1.

[19] Ian Rilen, Love is murder, Phantom Records, 2000.

[20] D Philips and S Davies (eds), A nation of rogues? Crime, law and punishment in colonial Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1994, p. 147.

[21] Special thanks to Pat Grainger and Maree Chalmers from the Port Melbourne Historical Society for answering my many questions and providing me with photographs of Port Melbourne.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples