Last updated:

‘Merely Corroborative Detail: The use of public records at the Sovereign Hill Museums Association, Ballarat’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 6, 2007. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Jan Croggon.

This article discusses the value and importance of public records for historians working in an outdoor museum such as Sovereign Hill. It points out that Sovereign Hill’s mission to depict the ‘mining, social, cultural and environmental heritage of Ballarat’ demands, in the first instance (and wherever possible) accuracy of re-creation. In projects such as the 1850s Government Camp (on which was based the accommodation complex at Sovereign Hill), and the Red Hill National School (a two-day, costumed school experience), the richness and detail of Victoria’s public records have enabled historians to describe the exact nature of the buildings as they existed in the nineteenth century. This, in turn, informed the architects and builders of Sovereign Hill’s own re-created buildings. The value of public records in developing the story of the Eureka Stockade has likewise been invaluable. The detail, the chronology, the players and participants — indeed, the basic integrity of our sound and light presentation is fundamentally reliant on the availability and accuracy of public records.

The detail which is such an intrinsic part of public records has always been of immense importance to historians attempting to understand, for example, the difficulties of establishing an education system on the goldfields, the nature of school curricula, the style and content of the textbooks, and the trials and tribulations of the teachers of the goldfields schools. Similarly, the accuracy with which public servants in nineteenth-century Victoria recorded the changing fortunes of police and government buildings on the goldfields provides not only wonderful detail of layout and elevation, but also gives us a window through which we may understand something of the nature of law and order on the goldfields of central Victoria.

Finally, the article identifies the value of public records in supplying some insights into the ‘essence’ of the Victorian age. The formality of the written word, and the richness of the language used, enabled Sovereign Hill’s historians to gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which public records might be said to have actually helped to shape the whole Victorian age.

Merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative …[1]

The value of public records as a rich source of information and insight for historians is fairly much beyond doubt these days. It is perhaps less clear how valuable such records can be for the historian working at an outdoor museum such as Sovereign Hill, where accuracy of re-creation has always been a high priority.

The Sovereign Hill Museums Association is a not-for-profit, community-based organisation structured as a company limited by guarantee. It is responsible for managing a network of museums whose mission is to:

… present, in a dynamic group of museums, the mining, social, cultural and environmental heritage of the Ballarat region and its impact on Australia‘s national story.[2]

One of the major problems with attempting to envisage and create a ‘whole’ environment (that is, the interior and exterior of a building, and its function) is that the nature of the private records left behind by the people of the gold rush are often incomplete, sometimes vague, and usually lacking in detail. However, over the years, one of the most significant resources for Sovereign Hill’s researchers has been the richness and strength of Victoria’s public records.

From the museum’s earliest days, public records have been used in many of our most important projects to establish accuracy and detail, and to impart meaning and understanding to their function. They have also been a source of wonderful, visual information for historians trying to re-create the life and colour of Victoria’s gold rushes. The use of public records, of course, is critical because at Sovereign Hill we are trying to re-create a township which really existed. ‘Making it up’ is not an option. Almost every building which has been re-created at Sovereign Hill is based on a real building which was present in Ballarat in the decade 1851-1861; the historian’s brief at Sovereign Hill is to provide visual, architectural reference for the building, and as much detail as possible about its function. How valuable, then, are public records, and how marvellous it has been when the opportunity has arisen for us to research a building which has been ‘on the public record’!

Use of public records at Sovereign Hill goes back to our earliest days, and continues to the newest projects. The list of projects covers a broad spectrum, and in itself is indicative of the range and depth of public records as they define a society:

- the Post Office;

- the Government Camp;

- the Chinese Village;

- the Red Hill National School;

- The Eureka Stockade (Blood on the Southern Cross).

In this article, there is only time to deal with a couple of these projects.

The Government Camp

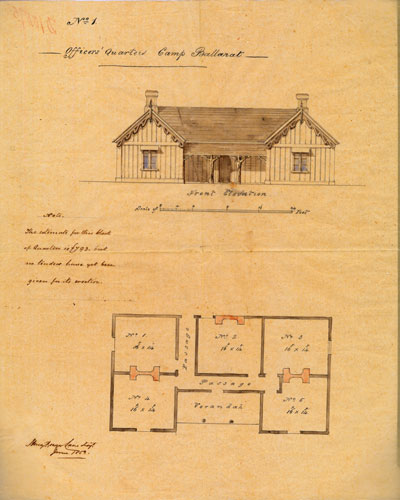

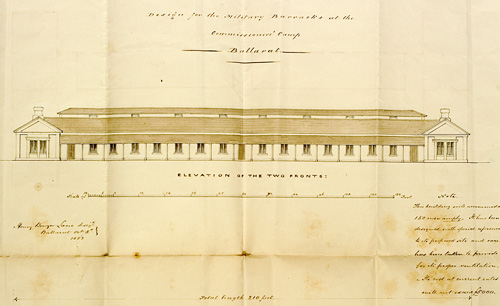

The Government Camp is an example of Sovereign Hill’s use of public records to supply a visual image of buildings. When, in the 1980s, Sovereign Hill was considering the provision of accommodation, on a site adjacent to the outdoor museum, a group of buildings was needed to fulfil this function. The organisation had for a long time been aware that its representation of the colonial administration at Ballarat needed to be developed. The historians went to work, and found that many of the plans for the 1850s Government Camp existed in mint condition at PROV. It was decided to re-create the exterior of the 1857 Government Camp, and build the interior to cater for modern accommodation needs. The buildings which we chose to re-create were designed principally by Henry Bowyer Lane, the Government Architect. They were simple but attractive weatherboard buildings, and the original plans and elevations are still held at PROV.[3]

PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, Unit 91, F54/5953.

Maps, plans and photos drawn from PROV records constituted the research material for the re-creation of the 1857 Government Camp.

Reproduced with permission from The Sovereign Hill Museums Association, Ballarat.

The Camp was the centre of colonial administration for the Ballarat Police District; it encompassed courts, judiciary, public administration such as business licences and health controls, police, military, gaol, gold licensing, gold escort and officials such as the Chinese Protector. A large-scale research effort was invested to produce the information necessary to establish the external appearances, general function and siting of the buildings of the Ballarat Government Camp. For interpretation purposes at Sovereign Hill, the period chosen to be represented was early 1857. Although the architect’s plans still extant for the Camp’s buildings were of the 1853/54 period, many of these buildings were known to be still standing in 1857. A plan of the Camp, drawn in February 1857, was available which indicated the dimensions of each building, the materials from which each building was made, and the building’s current function. Using this plan, together with the original architect’s elevations and early photographs of the area as references, Sovereign Hill re-created the Military Barracks, the Residence of the Superintendent of Police, the County Court and the building which was designed for the Officers’ Quarters. This latter building had several functions over the years, and in 1857 was in fact being used as offices by the Superintendent of Police and the Detective Police.[4]

Sovereign Hill’s choice of 1857 was in part dictated by the confusion which seemed to reign over the function and availability of the buildings loosely designated as the ‘Government Camp’. We needed to select a clearly defined set of buildings within what was a very fluid political environment. The military was in the process of moving out of Ballarat, and the police were taking charge, and moving into buildings hitherto occupied by the military. As well, the inadequacies of the constructed buildings meant that there were many complaints from those in authority at Ballarat who had to use them, and much detail about the nature of alterations to make them more appropriate to the need of the moment. Such disputes entailed heated written exchanges between the authorities in Ballarat battling with inadequate facilities, and colonial authorities in Melbourne. These disputes, in fact, were a bonus for Sovereign Hill, since the exchanges often revealed detail about the appearance and function of the building. As well, the correspondence begins to develop our understanding of the way in which colonial government and the goldfields administration actually functioned. More often than not, construction was arbitrary, and somewhat haphazard. Budgets were limited, and expedience ruled the day. Changes to mining regulations (for example, as a result of the Enquiry released in 1856 following the Eureka Stockade in 1854) also influenced the function and layout of the buildings; new incumbents in new positions of authority made new demands on colonial purse strings. The rationale of some buildings was adjusted, and their exterior appearance altered to suit. Public records relating to the Government Camp, in fact, demonstrate a fascinating interaction between the forces battling for political and physical supremacy in the city of Ballarat. The city’s transition from a military encampment (post-Eureka) to police administration is demonstrated many times in the letters which fly backwards and forwards between goldfields administrators, the military, and the police.[5] The volatility of the camp building functions, as they altered to suit each successive wave of inhabitants, caused Sovereign Hill researchers many headaches. It was therefore a challenge for Sovereign Hill to identify a set of buildings which all existed at the one time, and for which we could identify a function.

Sovereign Hill has, in the Government Camp project, harnessed an economic and functional requirement to an interpretive goal. Strong research using public records has provided the organisation with the historical basis on which to construct a much- needed resource. Although the Sovereign Hill Government Camp buildings are internally given over to twenty-first century accommodation, their physical presence overlooking the Township serves to remind us of the importance of colonial administration, and the dispensation of British law in the far-flung colonies of the Empire.

Reproduced with permission from The Sovereign Hill Museums Association, Ballarat.

The value of public records goes far beyond the unadorned information which they impart. They tell the story of the Victorian age, and reveal the essence of the Victorian people: they speak to the historian of an age when the printed word was virtually the only form of communication, and the only formal means of documenting the massive changes which were taking place in the world. In fact, it could be argued that their use of language, and the need to formalise and make clear every step of the official position, actually helped to shape the world in which they lived. The nineteenth century represents, in many ways, a more gracious, more considered lifestyle, where time flowed more slowly. Transport and communication was not instant. In a world of email, satellite communication, air travel, it is hard for us to comprehend that letters from Britain could take up to three months to arrive in Australia, and that communication between the seat of colonial government in Melbourne and the place of action, for example, Ballarat in December 1854, was the length of a horse ride away, probably a day’s ride. Such distances obviously placed other limitations, and had other effects, on the way events unfolded, but the pace of life clearly had to be slower and more considered. Public records, and their language, reflect this.

Eureka

Nowhere has the use of public records been more intense or more important than in the research carried out for The Sovereign Hill Museums Association’s presentation of Blood on the Southern Cross, which re-creates the story of the Eureka Stockade. This formative event in Australian history took place right in the middle of the decade represented at Sovereign Hill’s outdoor museum.

The strength and drama of the story, and its far-reaching consequences for the development of political democracy in Australia, demanded appropriate attention. It was decided to tell the story through a sound and light presentation, a magical interpretive device which provides a vivid sound and light ‘stage’, and invites the viewer to use his/her imagination to supply the actors. But in order to make the story come to life, the historians’ brief was to ensure that the detail, the chronology of events, the participants, and the set, were accurate down to the last detail. Where else could this detail be obtained, but through public records? The research task was daunting: the Sovereign Hill team was determined to ensure that the story told in Blood on the Southern Cross was true to the spirit of both sides of the story (miners and authorities), and so could offer visitors the opportunity to weigh up the facts and make up their own minds about what had happened in those momentous few days in December. We hoped that it might, perhaps, even offer them a chance to understand why it happened.

It was fortunate that in 1994, to mark the 140th anniversary of Eureka, Public Record Office Victoria mounted an exhibition to display part of its record-holdings relating to Eureka. The book of the exhibition contained more than 600 citations to official documents in the PROV holdings. This, as well as other public records,[6] was an invaluable resource for Sovereign Hill researchers.

The detail and the humanity with which the characters of Eureka are presented in their own documents is a unique asset: in their own words, the colonial administration proclaimed their confusion, fear and often misguided authority. In these preserved records we are able to detect the concern felt by government authorities as the situation in Ballarat deteriorated, and the determination of Commissioner Rede and Governor Hotham to uphold British justice in the face of perceived insurrection and treachery:

So long as the law which regulates the fee to be paid for licences is in force it must be maintained, otherwise Government is at an end and the Leaders of a Riot have obtained that which they contended for.[7]

Rede’s fear of loss of control, and his deeply felt obligation to restore and maintain order, and especially to communicate with and seek guidance and support from Governor Hotham in Melbourne, is very evident in these records:

The whole affair is a strong democratic agitation by an armed mob. If the Government will hold this and the other gold fields it must at once crush this movement, and I would advise again that this gold field be put under Martial Law, and artillery and a strong force sent up to enforce it.[8]

Almost all the elements of the Eureka story — the chronology, the aftermath, the actual physical realisation of the Eureka scenario — were part of the brief which we attempted to address in Blood on the Southern Cross. Had it not been for the depth and breadth of the public records available, our task would have been well-nigh impossible. The casualty lists, the State trial records, the minor players, all provided a wonderful canvas on which Sovereign Hill could paint its picture of the Eureka story.

There is not the scope in this paper to detail the value for Sovereign Hill researchers of the public records relating to Eureka. But it should be said that they provided the structure around which our interpretation of the event was based: the sound and light show drew extensively on the invaluable insights which the despatches and correspondence of the players in the Eureka drama revealed. Without these documents, our understanding of the fundamental issues of Eureka would have been limited indeed. Blood on the Southern Cross provides visitors with a dramatic, colourful, and evocative experience, but the bones of the story were already there in the public records.

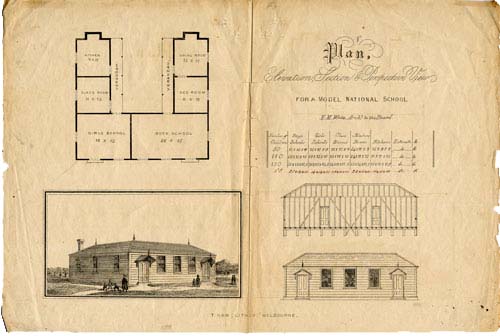

Red Hill National School

The re-creation of the Red Hill National School, the first in Sovereign Hill’s two-day costumed schools program, was also based on research into public records. The public record office in Laverton (where it was then based) was the scene of many long hours of research (in 1978) in efforts to locate and copy original records relating to education in the early days of the state’s history. Along with texts from the State Library of Victoria, these records provided the basis for the program which is still taught in the Red Hill National School at Sovereign Hill today, as it was in 1856, to the children on the Ballarat goldfields. The educational experience it provides for young students is probably unequalled anywhere in Australia, if not the world. Thankfully, non-denominational school records have always been part of the ‘public domain’ in Victoria, and the story we wanted to tell, and the information needed to bring it to life, was there for our researchers to find.[9]

For example, amongst the comprehensive collection held at PROV relating to National Schools, a particular gem comes to light relating to the somewhat inconvenient loss of the school building in 1856 owing to a ‘recent gale’:

Sir

I have the honour to inform you that a recent gale blew down the school in Warrenheip Gully and at present the school is being conducted in a building [not intended] for that purpose. Under these circumstances the Local patrons decided that the only course to pursue was to get a Building up at once. They therefore obtained permission from the Chief Warden, to erect it fronting the Main road at a distance of about 200 yards from the site of the former school. The building is to be 18 feet by 30 feet, all of colonial timber: with, 2 windows in front and 2 the back and roofed with shingles … to cost £80 and to be up in 5 days from this date. The contract was signed on Friday last and the Building started at once …[10]

PROV, VPRS 4857/P0 Plan For A Model National School, Unit 1.

Again, the records were not only a rich source of specific detail for Sovereign Hill historians, but provide us with another layer of understanding of the way in which education was carried out on the Victorian goldfields. The importance of schooling was almost always compromised by lack of funds, an itinerant population, and lack of commitment from both parents and the colonial government. Much of this debate is revealed in the reports and correspondence held at PROV, which paint a compelling picture of the frustrations and difficulties attendant on attempts by both government and community to provide the swelling goldfields population with adequate schooling. A letter from ‘The Correspondent of Patrons’ (William Coote) to Benjamin Kane, Secretary of the Board of National Education, relating to the erection of a new school house in October 1857, underscores this:

The first topic to which the patrons have to draw the attention of the Commissioners is the deficient accommodation provided by the Building now used as a school. In itself it is a mere shed, the weatherboarding defective, the framing bad, and the whole incapable of being [refixed?] whenever it is removed … the school stands upon ground required for the opening of one of the cross streets into the Ballaarat Main Road … the utter inadequacy of the shed to the purpose of education, would render such a step exceedingly undesirable. It is low, badly lighted, and worse ventilated. The maps and other objects which are usually hung upon the walls of a school cannot be exhibited for want of space. There is a canvas covered tent with damp earthen floor, now used as a classroom, and which is less fitted for its purpose than the school itself. The fittings are few and poor and totally inadequate to the requirements of the scholars. All this is very deplorable …

[regarding the inadequacy of the master’s residence]As matters are now the master has a most depressing influence -– that of domestic discomfort and even privation … and it is neither for the good of the school, his own good, or the reputation of the national system of education that they should remain in their present state.[11]

From Silver Threads among the Gold, 25th Anniversary of The Sovereign Hill School, Sovereign Hill, 2004, p. 63.

The struggles and small human crises of the men and women who taught in the schools on the Victorian goldfields are colourfully documented in the PROV records relating to the National Schools. For Sovereign Hill, history is not only about creating a built environment, but about using the bare bones of history to interpret to visitors the kind of society in which people lived and worked. Our own teachers are familiar with the public records relating to our re-created schools, and use this knowledge to create and present their own 1850s personality. Part of the Red Hill School program involves the visit of the school inspector, and this event features (amongst other things) the inspector quizzing the teacher and the students about the appropriateness of allowing the hapless teacher a pay increase, and some new and better accommodation. This has become a highlight of the program, and allows our staff to interpret those documents from PROV which identify the constant pleas from underpaid teachers for higher wages and better conditions.

To the Chairman of Patrons, Ballarat, July 15 1857

[B.F. Kane, Secretary, Board of National Education]Relative to House Allowance to Mr. Millie, Master of the Red Hill School,

As we have received no reply to our application for an allowance in lieu of house accommodation to Mr. Millie of the Red Hill National School, we again write to recapitulate the circumstance, to remind you of the same, and to request that a settlement may be made.

When the School was visited in July 1856 we found the place in which Mr. Millie lived to be uninhabitable, and that it could not be repaired. We then requested him to write a letter describing the condition of the dwelling, and at the same time making an application for house rent. This was done, we endorsed the letter, it was sent to you…

When the school was blown down in the month of September last, the dwelling (such as it was) was also rendered useless and since then no accommodation of any kind has been provided.

We would remind you that we signed Mr. Millie’s papers in January, claiming rent for the period during which he had had no accommodation of any kind and since then we have wrote (at least) two letters in explanation.

…

[signed] James Oddie[12]

The frustration of the Ballarat school administrators is obvious; one can only imagine how the hapless Mr Millie must have felt at such unfeeling treatment from the Melbourne-based National Education Board. Students at Sovereign Hill’s Red Hill School are given a precious insight into the precariousness of a teacher’s position in the 1850s when such situations are presented to them through the interaction between their ‘teacher’ and the school inspector. This one reference provides a single but compelling example of the important and vibrant detail available from public records.

Illustration taken from Silver Threads among the Gold, 25th Anniversary of The Sovereign Hill School, Sovereign Hill, 2004, p. 19.

The Chinese Village

The revitalisation of the Chinese village at Sovereign Hill is the most recent project in which we have used records from Public Record Office Victoria. Chinese petitions against the 1857 Residence Tax have enabled us to portray the Chinese perspective, whilst the Chinese Protectorate records have given us an understanding of how the system worked. The story of Chinese protests will be interpreted using multimedia technology.

Conclusion

At Sovereign Hill, each project is based on solid, directed research which provides the first, most substantial layer of the information and experience which we present to the visiting public. Other resources in the outdoor museum (the costume department, the engineering and maintenance department, the education department) ultimately rely on the accuracy and authority of the information supplied by the researchers. Successful marketing of the end ‘product’ is partly dependent on the claim to present an ‘authentic’ experience; finally, visitors themselves can be amazingly astute in sensing the integrity or otherwise of their encounters with nineteenth-century goldfields history.

The museum’s use of public records provides us with a fundamental honesty and truth on which we are able to base our efforts to tell the stories of one of the most exciting periods in this state’s history. To re-state the quotation that heads this paper, Sovereign Hill’s own narrative might well have been ‘bald and unconvincing’ without the wonderful ‘corroborative detail’ and ‘artistic verisimilitude’ supplied by the breadth and depth of Victoria’s public records.

Endnotes

[1] WS Gilbert, Pooh-Bah, in The Mikado.

[2] From ‘Staff and Volunteer Guide to Sovereign Hill’, Sovereign Hill Museums Association, 2004, p. 9.

[3] Drawings used in this article were sourced from VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Correspondence I, Unit 87, F54/5953 and Unit 91, D53/10472. Further contextual information can be found in PROV, VPRS 937/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence, Units 10-27 (Ballarat District); see also Units 432 and 434 (Public Works Department); Units 131 & 132 (Chief Secretary’s Department), Unit 350 (Military); and Unit 141 (Colonial Miscellaneous).

[4] List of Buildings re-created at Sovereign Hill Lodge: Residence areas, including Military Barracks (Student Accommodation), Residence of Superintendent of Police (or Residence) (Motel (Heritage style) Accommodation), and (Superintendent’s and) Officers’ Quarters, used as offices for Superintendent and Detective of Police in 1857 (Heritage Accommodation); Government Administration (Law and Order) areas, including Court House (dining, lounge room and reception area) and Chinese Protector’s Office (theme lounge and entry into Outdoor Museum); Equipment and Supplies areas, including Warden’s Stables (Recreation Area) and Quarter Master’s Store (Recreation Area).

[5] PROV, VPRS 937/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence, Units 432 and 433; also Units 10 and ff.

[6] Eureka Documents, 1. Three Despatches from Sir Charles Hotham, Public Record Office, Melbourne.

[7] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence I, Unit 101, R55, quoted in Ian MacFarlane (ed.), Eureka – From the Official Records, Public Record Office Victoria, Melbourne 1995, p. 19.

[8] Eureka Documents, p. 16, quoted from Enclosure, Rede to Hotham, Ballaarat, 30 November 1854.

[9] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence I, Unit 205.

[10] Letter from James Oddie to Chairman of Patrons Ballarat, intimating that the School Tent at Warreneep has been destroyed, and that another building has been erected, and respecting payment of accounts, 30 September 1856. PROV, VPRS 880/P0 Inwards Registered Correspondence, Unit 4, 56/1785.

[11] PROV, VPRS 880/P0 Inwards Registered Correspondence, Unit 4, 57/2334.

[12] Letter from James Oddie 15 July 1857 to The Chairman of Patrons, Ballarat, relative to House allowance to Mr Millie, Master of the Red Hill School, PROV, VPRS 880/P0 Inwards Registered Correspondence, Unit 4, 57/1618.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples