Last updated:

‘Superintendent La Trobe and the amenability of Aboriginal people to British law 1839-1846’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 8, 2009. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Frances Thiele.

This is a peer reviewed article.

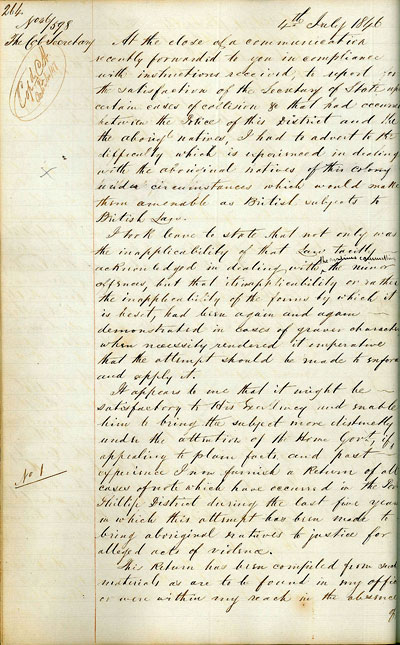

In July 1846 the Superintendent of Port Phillip, Charles Joseph La Trobe, sent the Colonial Secretary in Sydney an extensive report about a matter of great importance to him – the effective prosecution of criminal cases involving Aboriginal people. By the mid-1840s the continual problems that beset prosecutions of this nature frustrated La Trobe to the extent that he decided to restate the issues clearly in a long letter, outlining the considerable confusion that existed about the legal status of Aboriginal people, evidentiary law and the role of magistrates in criminal cases. La Trobe expected that his presentation of ‘plain facts and past experience’ of the matter would enable the New South Wales Governor to ‘bring the subject more distinctly under the attention of the Home Government’. This was not the first time La Trobe had brought the problematic character of judicial proceedings to the attention of colonial authorities. As superintendent, he attempted to highlight what he thought were defects in the criminal justice system. Ultimately his efforts did little to change legal practice but are a valuable insight into his approach to Aboriginal issues and the difficulties he faced while attempting to fulfil one of his most important duties – the improvement of conditions for Aboriginal people and the resolution of conflict in a rapidly expanding white society.

Charles Joseph La Trobe arrived in the Port Phillip District in October 1839 he believed emphatically in a dual approach to improving conditions for those Aboriginal people who were suffering as a result of European settlement.[1] A Colonial Office appointment, La Trobe agreed with the British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord John Russell, that it was the government’s ‘sacred duty’ to compensate Aboriginal people for the taking of their land by giving them the ‘blessings of Christianity’ and the ‘advantages of civilized life’.[2] While a belief in God would take care of their spiritual well-being, La Trobe believed that the application of British law would protect Aboriginal people and settlers alike. He also agreed with the British Government policy that ‘English Law would be a means of civilising indigenous people’.[3] God and the law were the mainstays of La Trobe’s approach to ensuring a peaceful co-existence of Aboriginal people and Europeans in his District. Unfortunately, neither was particularly successful. While La Trobe could offer few ideas for the improvement of missionary endeavours towards the Aboriginal community, he repeatedly tried to draw attention to the problematic character of criminal cases involving Aboriginal people.

On taking up his appointment as Superintendent, La Trobe soon became aware of the extent of violence occurring between the settlers and the Aboriginal population. In October 1840 he reported to the Colonial Secretary the ‘continued and increasing acts of aggression by the natives on the property of the settlers, and the acts of reprisal to which they give rise in the Port Phillip district’.[4] Armed with a heightened sense of right and wrong and an adherence to a notion of justice based on the revelatory power of the ‘truth’, La Trobe ordered the Chief Protector of Aborigines and his Assistants to investigate any acts of aggression.[5] The varying success of the Protectors’ enquiries quickly brought to La Trobe’s attention the numerous challenges that inhibited the judiciary when bringing cases to trial.

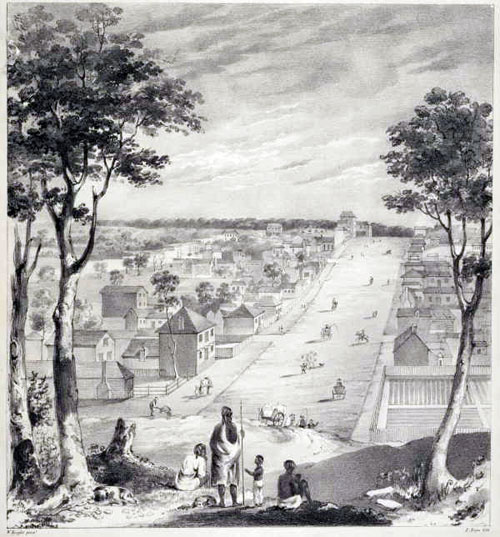

Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Established as a result of the British Government’s Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate plan, the Protectors formed part of the Chief Protector’s Department in La Trobe’s public service. In 1835 the British Parliament had appointed a Select Committee to investigate the ‘condition of Aborigines’ in British colonies and develop appropriate policy. The Committee’s investigations prompted them to propose the trial of an experimental protectorate system in Australia. In its report of 1837 the Committee made some general statements about how the system would work and suggested the employment of ‘Protectors’ for Aboriginal people. By the end of 1837 the Colonial Office decided to adopt the system in the newly created Port Phillip District of New South Wales. The head of the Colonial Office at the time, Lord Glenelg, appointed four Assistant Protectors and one Chief Protector for this purpose. George Augustus Robinson, the Chief Protector, gave each of his Assistants a specific area of Port Phillip in which they were to settle and take responsibility for the welfare of the Aboriginal people who lived there. Glenelg advised the Governor of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps, about the plan at the beginning of 1838 and expected the New South Wales Government to fund it.[6] The Chief Protector was to undertake the actual daily management of the Protectorate under the cautious supervision of La Trobe.

The system adopted in Port Phillip was unique in an Australian context at this time. In 1839 the Colonial Office appointed a single Aboriginal Protector in South Australia, Matthew Moorhouse, but did not adopt a protectorate system on the scale of that initiated in Port Phillip. The Colonial Office believed that a single Protector was all that would be required in South Australia, given the small size of the proposed settlement on Kangaroo Island compared to the size and popularity with settlers of the Port Phillip District.[7] The Colony of New South Wales did not appoint a ‘Protector of the Aborigines’ until 1881.[8]

As envisaged by the Select Committee, the duties of the Protectors included some legal responsibilities. The Protectors were to act as magistrates and initiate legal proceedings in the event of an attack on any member of the Aboriginal community or their property. If an Aboriginal person within their area was accused of a crime, it was the duty of the Protector to ‘undertake and superintend the defence of the accused party’.[9] The Committee also suggested that the Protectors act as coroners and investigate all instances in which an Aboriginal person was ‘slain’. Finally, in recognition of some of the difficulties the Protectors might experience fulfilling these duties, the Select Committee proposed that the local government adopt ‘such short and simple rules as may form a temporary and provisional code for the regulation of the Aborigines, until advancing knowledge and civilization shall have superseded the necessity for any such special laws’.[10]

Unfortunately, most of the Protectors resented being asked to act in a magisterial capacity and, like other magistrates appointed in the Port Phillip District at this time, had little legal knowledge or experience.[11] Three of the Protectors, James Dredge, William Thomas and Edward Stone Parker, owed their appointment to their association with the Wesleyan Church. All three men accepted their positions in Port Phillip because of the opportunity they would have to convert Aboriginal people to Christianity. They were lay preachers with earnest missionary-like aspirations and the Colonial Office had led them to believe that this would be a major aspect of their role in Port Phillip. One of their earliest tasks upon arrival in Melbourne, however, had been to undertake criminal investigations. When James Dredge resigned his position in February 1840, he complained about the overemphasis of his work on secular rather than spiritual matters. Dredge believed his role as a Protector would be ‘as much as possible of a missionary character’. The reality of his situation was quite different:

Upon my arrival in this country, I was informed that the office would be one of an entirely civil character; and I was subsequently appointed a magistrate, a distinction I never coveted, but one, so far as I was concerned, almost entirely nominal, inasmuch as I received instructions that I was not to act in a magisterial capacity, not even to issue a warrant for the apprehension of an offender, should I be applied to for that purpose under the most urgent circumstances, unless the aborigines were concerned.[12]

The Protectors did not know how to act as magistrates. Their first efforts at investigating crimes involving Aboriginal people were disastrous, eroding La Trobe’s idealism about justice wrought from the rule of law.

In their magisterial role the Protectors were to assist in the determination of whether or not an offence had been committed, take any depositions required for prosecution of a case and make any necessary arrests. Just two months after arriving in Melbourne La Trobe had cause to question the Protectors’ capacity to undertake this aspect of their duties. In mid-1838 Chief Protector Robinson directed Assistant Protector Parker to investigate a possible ‘affair’ between the Mounted Police and a group of Aboriginal people on the Campaspe River. La Trobe forwarded Parker’s findings and the statements that he took in evidence to Sydney for review by the Attorney-General, who would prosecute the offenders if there was a case to answer. Parker believed that the Mounted Police shot as many as forty Aboriginal people during the incident, nearly the entire clan.

Parker cited the source of his knowledge as ‘private information’.[13] The Attorney-General, however, questioned the reliability of this source and requested that Parker name his informant. Parker had to admit his information was second-hand from someone he trusted but that ‘a man whose veracity could not be depended on’ made the original statement. At this point the whole case began to fall apart. La Trobe lamented that ‘The proper measures to elicit the truth have evidently never been taken, and delay of seven or eight months in setting on such foot [sic], cannot be otherwise than productive’.[14] The Superintendent sent Robinson to assist Parker in his magisterial duties and effectively begin the investigation again. No matter how badly the case had been dealt with, wrote La Trobe, ‘no time is now to be lost in bringing the circumstances of the case before the Attorney-General in such a form as may facilitate the ends of justice’.[15]

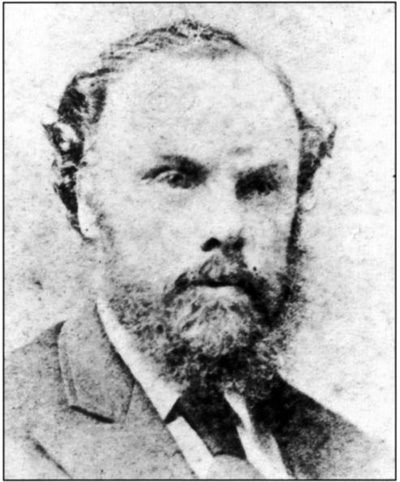

Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria.

At the beginning of 1840 Robinson decided it was necessary to seek some clarification from La Trobe about the magisterial functions of the Protectors. La Trobe had attempted to avoid the embarrassment of Parker’s poor depositions in the 1839 case involving the Mounted Police by ordering that the Protectors send all their depositions initially to a local authority for review. All papers connected with their magisterial duties were to be sent to the Crown Prosecutor James Croke who, wrote La Trobe, ‘will be able to judge if the papers are sufficiently complete and in such form as may render their transmission to the Attorney General advisable and proper’.[16] Robinson sought official acknowledgement of this decision and also asked La Trobe ‘whether, in Judicial cases the Assistant Protectors are to take part in the defence of the Aboriginal natives of their respective districts?’.[17] This was a more difficult question to answer and La Trobe’s response revealed the uncertainty surrounding the prosecution of Aboriginal cases at the time.

La Trobe argued that it was ‘unquestionably’ the responsibility of the Protector to present any evidence he had in favour of the accused where the latter were from his district. The Protector was not, however, to act as a legal representative. ‘I doubt the propriety or wisdom’, stated La Trobe, ‘of his considering himself in the same light as a lawyer who having received a fee, is bound to uphold or defend the cause in hand whether it be good or bad’.[18] To what extent the Protector was able to interfere in a case beyond the presentation of evidence, La Trobe did not know and referred the matter to the Governor.

The lack of clarity about the magisterial role of the Protectors was particularly evident towards the end of 1840 when another of the four original Assistant Protectors, Charles W Sievwright, complained that the government had not prosecuted any individuals responsible for Aboriginal deaths in his district. Submitting his report for the months of June to October, Sievwright declared his outrage that ‘legal authorities have not yet thought fit to bring to trial . . . any of those implicated in the appalling sacrifices of life that have taken place among the aboriginal natives of the Western District’.[19] La Trobe reported to the Colonial Secretary in November that much of this state of things was due to Sievwright’s own incapacity to undertake his duties and obstinacy in seeking advice.

Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Crown Prosecutor Croke declared that he had returned depositions taken by Sievwright because they were not ‘taken in accordance to the rules of law’.[20] Under these rules a person confessing a crime could not give a deposition under oath and must confess voluntarily. As Croke explained: ‘The reason why principals should not be examined on oath is, because the dread of perjury, coupled with the apprehension of additional penalties, may create an influence on their minds which the law is particularly careful in avoiding’.[21] Sievwright had done just this, taking a deposition from two brothers who confessed to murdering several Aboriginal people. Croke warned that this evidence was inadmissible. Sievwright was not the only Protector to make this mistake but both the Attorney-General and Croke had consequently outlined to the Protectors the correct procedures they should follow when undertaking their magisterial functions. Sievwright did not act on this advice. La Trobe, at a loss to explain this behaviour, concluded that ‘No decided step has been taken by him in any of the lamentable cases of collision between the settlers and aboriginal natives of his district, although it appears to me that if his opinion of the character of the homicides in question were really that which he conveys, it was clearly and imperatively his duty to do so’.[22]

In 1841 the Chief Protector reiterated the Select Committee’s recommendation that the government should initiate a special legal code for Aboriginal people. The Committee had suggested that this should be a duty of the Protectors but their lack of legal knowledge made this completely impractical. This suggestion was part of a larger debate about the creation of ‘exceptional laws’ that would modify British law for Aboriginal peoples and ‘set provisos and exemptions from English criminal law, particularly in terms of procedure and penalities’.[23] While La Trobe regretted that the ‘inexperience’ of the Protectors was creating some obstacles to the effective prosecution of cases, he understood that there were other issues as well. The size of the Port Phillip District, the large distances between squatting runs, the small number of police, the difficulties of communication and problems with finding witnesses and interpreters all hampered the administration of justice.[24] When it came to finding a reason for the low number of cases actually brought to trial, however, La Trobe cited the ‘manifest difficulty of securing an unbroken chain of unimpeachable evidence whether direct or circumstantial’ and the ‘inadmissibility of aboriginal evidence in any shape’.[25]

In 1846 La Trobe drew attention to these issues in relation to Aboriginal criminal cases in a detailed report to the Colonial Secretary. He pointed out that the undefined nature of judicial proceedings gave judges considerable autonomy in the way they treated Aboriginal prisoners. In many cases a judge based the legitimacy of a trial on the level of ‘civilisation’ he thought the accused demonstrated. La Trobe referred to this as the ‘mental capacity question’.[26] In such cases a judge measured the degree to which an Aboriginal person was ‘civilised’ by the extent to which they had become European. The ‘mental capacity question’ demonstrated the ubiquity of British cultural and racial assumptions about Aboriginal people. During the nineteenth century most Europeans thought black people were inferior to whites and positioned far below them on a ‘great chain of being’ or evolutionary scale.[27] Justice was often only available to Aboriginal people who were able to show a capacity for the English language and way of life. In the case of Koort Kirrup, which La Trobe singled out as a rare example, many of the difficulties of prosecution were evident but eventually overcome, and La Trobe argued:

His character for [sic] intelligence, and long intercourse with Europeans, to which many bore witness in the District where the crime was perpetrated, would seem to set his mental capacity, as far as comprehending the nature of the crimes with which he stood charged, and the object and general intention of the form of proceedings to which he was subject, beyond doubt.[28]

Initially, however, the judiciary found that Koort Kirrup was not ‘professed of sufficient degree of intelligence to comprehend the proceedings’ and set him free to return to his community even though he was later found guilty.[29] La Trobe took issue with the ‘mental capacity question’, not because he questioned its validity but because it was not raised in all cases, and even in those in which it was, the accused was not always asked if they understood that they could cross-examine European witnesses. This resulted in several miscarriages of justice, prompting La Trobe’s attempts to put the whole subject under scrutiny. La Trobe was left with the ‘strong impression’ that the application of the law in such cases was of an ‘uncertain and varying mode’.[30]

The admissibility of Aboriginal evidence was a corollary to the determination of ‘mental capacity’ and ‘civilisation’. The accused needed to comprehend the charges against them and be able to submit a plea, which ‘must be accompanied and verified on oath’.[31] If an Aboriginal person could not swear an oath, determined by their belief in God and an afterlife, then their testimony was inadmissible. Institutionalised through British law, Christianity was the dominant religion of European settlers in Australia and contemporary commentators often described Aboriginal beliefs as crude and unenlightened in comparison. The acceptance of Aboriginal evidence would require an alteration of the law as it was applied in the Australian colonies and an understanding, or at least a tolerance, of Aboriginal spiritual beliefs. In such a circumstance the British Government needed to acknowledge that Aboriginal people were not subject to the law in the same way as other British citizens, and to take some account of Aboriginal customary law. The extent to which the Colonial Office accepted or ignored Aboriginal law was dependent upon the degree to which it assessed Aboriginal peoples as ‘civilised’ or ‘uncivilised’.[32]

The British Government, aware of the need for the acceptance of Aboriginal evidence in legal cases, had been attempting to clarify this issue before La Trobe became Superintendent. Lobbying in the British Parliament and of the Colonial Office by the Aborigines Protection Society in London had brought the matter to the attention of the government. The membership of the Aborigines Protection Society included several parliamentarians who were able to bring the subject ‘under the notice’ of the British Parliament in 1838.[33] By the beginning of 1839 a sub-committee of the Aborigines Protection Society had prepared a Bill for the acceptance of Aboriginal evidence that they planned to present in Parliament. In July the Society decided instead to allow the Colonial Office to deal with the matter after extracting a promise that measures for the adoption of the Bill would be pursued through the Colonial legislature.[34]

Thomas Fowell Buxton, president of the Society and chair of the 1835 Select Committee on Aborigines, had personally spoken to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, presenting the Society’s position on the issue.[35] Buxton found Glenelg sympathetic to his views on the law as it applied in the colonies, which was not surprising given that the two men had much in common as abolitionists and Christian evangelicals.

The Society followed up Buxton’s communication with a letter arguing that:

It is evident that the rejection of the evidence of these natives renders them virtually outlaws in their native land, which they have never alienated or forfeited. It seems to me a moral impossibility that their existence can be maintained when in the state of weakness and degradation which their want of civilization necessarily implies, they have to cope with some of the most cruel and atrocious of our species, who carry on their system or profession with almost perfect impunity so long as the evidence of native witnesses is excluded from our courts.[36]

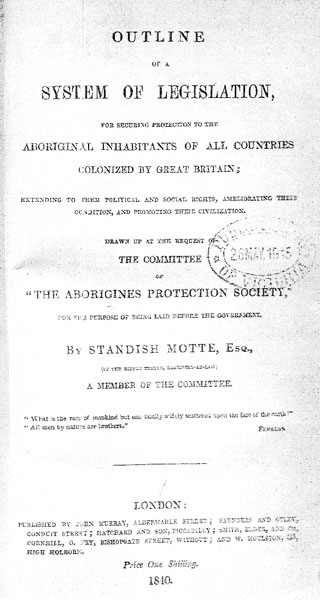

In February the Marquess of Normanby took over from Glenelg as the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, but the official Colonial Office policy remained the same and Normanby upheld Glenelg’s commitment to the Society. Normanby wrote to Gipps requesting that he present a Bill on the matter to the New South Wales Legislative Council.[37] The Aborigines Protection Society, still frustrated by the problems that beset the application of law in all the British colonies, decided to ask the lawyer Standish Motte to prepare an outline of proposed legislative changes they thought would protect Aboriginal people. The Society published Motte’s Outline of a system of legislation for securing protection to the Aboriginal inhabitants of all countries colonized by Great Britain in 1840.[38]

Pre-empting Normanby’s instructions, the New South Wales Attorney-General had already advised Gipps of the necessity of such legislation. At the end of 1838 he had introduced the Aborigines Evidence Bill into the Legislative Council to ‘allow the Aboriginal Natives of New South Wales to be received as competent witnesses in Criminal Cases’.[39] This legislation only ensured the acceptance of Aboriginal statements in court where circumstantial evidence or non-Aboriginal testimony supported it.[40] The Legislative Council passed the Bill but entered a clause requiring the British Government to sanction the legislation before it came into official operation.[41] Meanwhile in the Colonial Office Normanby sought further information about what was going on in colonial legal cases and confirmation of the claims of the Aborigines Protection Society.

The New South Wales Supreme Court Judge WW Burton informed the Colonial Office that the local judiciary could ignore Aboriginal evidence in two instances:

First, where it has been impossible to communicate with a proposed witness on account of his ignorance of the English language and when no interpreter could be found to interpret between him and the court; and, secondly, where a proposed witness has been found to be ignorant of a Supreme Being and a future state.[42]

In October 1839 Gipps sent a copy of the Aborigines Evidence Bill to Normanby who referred the matter to the British Attorney and Solicitors General.[43] A year later the new head of the Colonial Office, Lord John Russell, wrote to Gipps stating that the Act had been ‘disallowed’ on legal advice because ‘to admit in a Criminal case the evidence of a witness acknowledged to be ignorant of the existence of a God or a future state would be contrary to the principles of British jurisprudence’.[44] The colonial law officers upheld a ‘strict application’ of British law at this time but a change of government and the appointment of a new Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in 1841 meant that similar Bills were allowed in Western Australia and South Australia.[45] The New South Wales Government narrowly missed the opportunity to have its Bill ratified and consequently improve the chances of a fair trial for Aboriginal people throughout the colony.

In 1844 the New South Wales Attorney-General tried to introduce the Bill a second time to the Legislative Council but to no avail. The Council was now partially composed of elected members, and the squatters, who were in effect occupying Aboriginal land, were able to exert more influence than before.[46] The councillors dismissed the Bill at a second reading following a ‘vociferous debate’ in which William Wentworth declared that ‘[it is] quite as defencible [sic] to receive as evidence in a Court of Justice the chatterings of the ourang-outang as of this savage race’.[47] Not everybody was happy with this decision. As a local newspaper editor complained, the denouncement of the Bill was ‘an act of rank injustice’ and ‘until some law is passed which will give the aborigines a standing in our courts of law, and admit their evidence at its fair value, no system of police which the colony is capable of supporting can afford them protection from the outrages of the more lawless and immoral whites’.[48] The British Government had made the reintroduction of the Aborigines Evidence Bill to the Legislative Council possible by giving the local legislature jurisdiction to make laws of this nature in 1843.[49] The British had relinquished their control over this aspect of the law but the situation for the Aboriginal people of Port Phillip remained the same: ‘The formal legal position was that Aborigines were British subjects, but New South Wales was left without any means to begin to give them access to the British version of justice. They were subjects without enforceable rights.’[50]

The amenability of Aboriginal people to British law in New South Wales determined the admissibility of Aboriginal evidence. In 1842 Gipps proposed to present a Bill to the Legislative Council ‘to declare that the aborigines are amenable to our courts of law, like any other of Her Majesty’s Subjects’.[51] Gipps argued that the British had proclaimed the sovereignty of Great Britain over the Australian colonies and established the primacy of British law. As British subjects, Aboriginal people should be subject to this law. In rejecting the Aborigines Evidence Bill the British Government had already established that no special consideration would be made for the original inhabitants of the Colony of New South Wales. If Aboriginal people were British subjects then they had to abide by the British legal code, regardless of whether or not they understood it. If Aboriginal people could not swear an oath then their evidence was inadmissible. Only British law would prevail and there was no room for a separate legal code for Aboriginal people or other exceptional laws.

Gipps was responding specifically to cases in which Aboriginal people committed offences against each other. In September 1841 Justice John W Willis had questioned the legitimacy of a case brought before him at the recently established Supreme Court in Melbourne, giving his opinion that ‘aborigines are not amenable to our courts of justice for offences committed inter se, though they may be . . . for offences committed on the person of white men’.[52] Gipps wanted the matter settled; either Aboriginal people were subject to the law or they were not. Chief Justice Dowling and the other Sydney judges had no hesitation in reassuring Gipps that in their legal opinion British law applied to Aboriginal people regardless of whether a crime was committed against a European or another Aboriginal person.[53] Willis’s Sydney colleagues saw him as a rogue who, in querying his own jurisdiction over matters between Aboriginal people, went against the legal precedent of the 1836 case of Jack Congo Murrell. In the Murrell case three Supreme Court judges ruled that Aboriginal people were subject to British law even in ‘tribal situations’.[54] The issue was finally resolved when the Colonial Office agreed with Gipps, stating that, as the Sydney judges of the Supreme Court all concurred, there was no need for a declaratory law or official statement of policy. Instead, the amenability of Aboriginal people to British law ‘must be held to be the law of the colony’.[55] Ultimately the argument derived from a difference of opinion about the nature of British settlement in Australia. For Willis, Aboriginal people were entitled to continue their own customary law because he believed it had not been ‘extinguished’ by ‘an express statutory provision, by conquest, or by the cession of jurisdiction from the Aborigines by treaty’.[56] Willis’s controversial views, which were so contrary to the prevailing opinion of the Colonial Government, were partly responsible for his dismissal as a judge of the Supreme Court in 1843.[57]

In practice, the robust assertion of the supremacy of British law in New South Wales to the exclusion of Aboriginal evidence or the consideration of an adapted legal code, meant that a fundamental obstruction to justice in Port Phillip remained. In August 1841 La Trobe decried the circumstance that in ‘scarcely a single instance have the parties implicated in these acts of violence, whether native or European, been brought to trial; and in not a single instance has conviction taken place’.[58] Robinson similarly remonstrated against the futility of attempting to seek redress for violent crimes perpetrated against Aboriginal people. ‘Bringing the guilty to trial was almost “impossible”‘, he wrote, when in nine out of ten cases the only witnesses to violence committed against Aboriginal people are Aboriginal people themselves whose ‘evidence is not admissible’.[59]

During La Trobe’s superintendency of Port Phillip the judiciary did not convict a single European for the murder of an Aboriginal person, although the courts sentenced six Aboriginal people to death for attacks on whalers and settlers.[60] In cases where a European was the accused, Aboriginal testimony was not recognised and any other witnesses were unlikely to inform on a fellow settler. Where an Aboriginal person was the accused there was the ready acceptance of testimony from settlers and little opportunity for an Aboriginal person to offer a defence. As La Trobe put it,

Were the murder committed by the blacks, there were no witnesses, or no chance of identifying the parties; and were the natives the sufferers, the settlers and their servants, who were the principals in the first or second degree, were the only persons from whom evidence could be obtained. Aboriginal evidence brought forward, in the existing state of the law, could not be received.[61]

Saddened by the miscarriage of justice that was often the result, La Trobe tried to intervene. In 1842 he requested a reprieve for an Aboriginal man he thought the courts had wrongly convicted, while in other circumstances he objected to Gipps that people whom he believed had committed terrible crimes went free.[62]

La Trobe deplored the violence that was occurring in Port Phillip and meted out his disapproval of Aboriginal and European criminals alike. He was a highly principled individual who abhorred the inequality of the legislative system and the lack of morality it inevitably highlighted. When La Trobe heard about an unprovoked attack by settlers that left three Aboriginal women and a young child dead, he was appalled. More distressing was the request for protection from some of the settlers in the area, including those he knew were involved in the murder. In reply La Trobe called down ‘the wrath of God’ against those responsible for the murders. As to the others, he implored them to purge ‘yourselves, and your servants, from all knowledge of and participation in such a crime, never to repose until the murderers are declared, and your district relieved from the stain of harbouring them within its boundaries’.[63] At the same time he knew that ‘some of the most startling instances of murder which the aboriginal natives may from time to time have perpetuated upon Europeans, have been perpetrated with the most perfect impunity’.[64]

By 1845 the violence between Aboriginal people and settlers began to decrease and the issue of Aboriginal evidence appeared less relevant. The following year the new Governor of New South Wales, Sir Charles FitzRoy, asked La Trobe to determine the fate of the British protectorate plan, which had failed to achieve any of the aims the Colonial Office had anticipated. La Trobe’s negative appraisal of the efforts of the Chief Protector’s Department, and questioning of the need for the Protectorate at all, weakened British control over local Aboriginal policy. In 1847 the head of the Colonial Office, Earl Grey, decided to respond to La Trobe’s extensive examination of criminal cases in Port Phillip written the year before.[65] The news was not encouraging. Grey pointed out that the British Parliament had already transferred jurisdiction to the New South Wales Legislative Council in its Act of 1843 and declared the ‘defective state’ of legal proceedings involving Aboriginal people the concern of the local legislature. Most disheartening of all were Grey’s final comments. He admitted that it was ‘to the care and vigilance of the Executive Authorities alone, that we can trust for such an application of the Law as may effectively ensure the Administration of justice and the prevention of those crimes of which the Natives are either the perpetrators or the victims’.[66] In reality, however, wrote Grey, ‘To exempt the administration of the Law from cumbersome formalities and superfluous rules is, as you are well aware, an attempt of almost hopeless difficulty’.[67]

La Trobe seems to have resigned himself to this response from the Colonial Office. He had done his duty in pointing out the inadequacies of the system but little had changed. Grey supported and understood La Trobe’s arguments but in the end it was the responsibility of the Colonial Government. Following the disappointment of the failure of the Protectorate experiment, the British Government gradually lessened its control over Aboriginal policy in New South Wales. In 1848 Grey wrote to FitzRoy about the acceptance of Aboriginal evidence: ‘This is a question of the first importance; but as I have already, in my Despatch No.176, of the 25th of June last, pointed out the remedy, which is within the power of the Local Legislature, [is to alter] the Law of Native Evidence.’[68] The Legislative Council, however, had made its position clear and a year later the councillors rejected yet another attempt to pass the Aborigines Evidence Bill.[69] Squatters in the New South Wales government were successfully able to block any legislative reforms in favour of Aboriginal people during the period of La Trobe’s superintendency.

Despite his failed attempts to alter the way the judiciary prosecuted individual criminal cases in Port Phillip, La Trobe upheld his belief in the pre-eminence of British law. He was confident that the pursuit of justice would lead to improved conditions for Aboriginal people and the ‘prevention as far as possible of collisions between them and the Colonists.’[70] In 1849 La Trobe reassured Governor FitzRoy that: ‘The terror of the law, also, undefined as it may be, is felt among many of the tribes and is in his favour. It is understood that … there are means at hand which may follow up the perpetuation of outrage, and how, or by what process it matter not, subject him to coercion, if not to severe punishment.’[71] By the 1850s the notion that Aboriginal people were British subjects fully amenable to British law was an established part of legal theory.[72] The Colonial Office had pursued this policy throughout La Trobe’s superintendency of Port Phillip, believing that an assertion of Aboriginal legal equality would elevate their status and situation in the Australian colonies. When La Trobe called for an improvement in legal process to make Aboriginal people ‘amenable as British subjects to British Law’, he did so as an adherent to a humanitarian ideal in which British law represented ‘civilisation’ and protection for Aboriginal people. While he acknowledged that there were many obstructions to the proper functioning of the law when Aboriginal people were involved, La Trobe never relinquished his belief in the efficacy of the British legal system.

Endnotes

[1] Research for this paper was made possible as a result of a La Trobe Society fellowship awarded in 2007. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to the Society for supporting my work and to La Trobe University, which appointed me an honorary research associate in the School of Historical and European Studies the same year.

[2] Lord John Russell to Sir George Gipps, 21 December 1839, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, with the reports of the Protectors of Aborigines, and any other correspondence to illustrate the condition of the Aboriginal population of the said Colonies, from the date of the last papers laid before Parliament on the subject, (paper ordered by the House of Commons to be printed, 12 August 1839), Paper no. 627, House of Commons, London, 1844, p. 25.

[3] Damen Ward, ‘Savage customs’ and ‘civilised laws’: British attitudes to legal pluralism in Australasia, c. 1830-48, Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, London, 2003, p. 1.

[4] CJ La Trobe to the Colonial Secretary, 21 November 1840, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 139.

[5] AGL Shaw (ed.), Gipps–La Trobe correspondence 1839-1846, Melbourne University Press, 1989, p. 21.

[6] Lord Glenelg to Sir George Gipps, 31 January 1838, in Commonwealth of Australia, Historical Records of Australia. Series 1, vol. XIX, The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, Canberra, 1923, pp. 252-5.

[7] Michael Cannon (ed.), Historical records of Victoria: foundation series, vol. 2A, The Aborigines of Port Phillip, 1835-1839, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1982, pp. 19-27.

[8] Anna Doukakis, The Aboriginal people, parliament & ‘protection’ in New South Wales 1856-1916, The Federation Press, Sydney, 2006, pp. 8, 34. Other Australian states and territories, such as Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, did not appoint an official Aboriginal Protector until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

[9] Report from the Select Committee on Aborigines (British Settlements) with the minutes of evidence, appendix and index, Paper no. 425, House of Commons, London, 1837, p. 84.

[10] ibid.

[11] In 1841 Judge Willis complained that the magistrates in Port Phillip were not doing their duty or taking depositions correctly, causing problems when cases came to court. See Shaw, Gipps–La Trobe correspondence 1839-1846, p. 77.

[12] James Dredge to GR Robinson, 17 February 1840, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 54.

[13] CJ La Trobe to GA Robinson, 31 December 1839, PROV, VPRS 16/P0 Superintendent, Port Phillip District Outward Registered Correspondence, 1839-1851, Unit 1, Item 39/210.

[14] ibid.

[15] CJ La Trobe to FB Russell, 31 December 1839, PROV, VPRS 16/P0, Unit 1, Item 39/211.

[16] CJ La Trobe to GA Robinson, 30 March 1840, PROV, VPRS 16/P0, Unit 1, Item 40/126.

[17] ibid.

[18] ibid.

[19] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 26 November 1840, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 140.

[20] ibid.

[21] James Croke to CJ La Trobe, 17 June 1840, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 142.

[22] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 26 November 1840, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 141.

[23] Ward, ‘Savage customs’ and ‘civilised laws’, p. 16.

[24] CJ La Trobe to the Colonial Secretary, 4 July 1846, PROV, VPRS 16/P0, Unit 16, Item 46/598.

[25] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 28 August 1841, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 134; CJ La Trobe to the Colonial Secretary, 4 July 1846, PROV, VPRS 16/P0, Unit 16, Item 46/598.

[26] CJ La Trobe to the Colonial Secretary, 4 July 1846, PROV, VPRS 16/P0, Unit 16, Item 46/598.

[27] Russell McGregor, Imagined destinies: Aboriginal Australians and the doomed race theory, 1880-1939, Melbourne University Press,1998, pp. 5, 9.

[28] ibid.

[29] ibid.

[30] ibid.

[31] ibid.

[32] Ward, ‘Savage customs’ and ‘civilised laws’, pp. 7-8.

[33] Aborigines Protection Society, The Second Annual Report of the Aborigines Protection Society, presented at the meeting in Exeter Hall, May 21st, 1839, P White & Son, London, 1839, p. 16.

[34] Aborigines Protection Society, Extracts from the Papers and Proceedings of the Aborigines Protection Society, William Ball Arnold, London, 1839, no. 3, p. 67.

[35] Aborigines Protection Society, The Second Annual Report of the Aborigines Protection Society, pp. 20-21.

[36] Aborigines Protection Society to the Colonial Office, 30 July 1839, in Michael Cannon (ed.), Historical records of Victoria, vol. 2B, Aborigines and Protectors, 1838-1839, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1983, p. 758.

[37] Marquess of Normanby to Sir George Gipps, 17 July 1839, in Historical records of Australia. Series 1, vol. XX, The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, Canberra, 1924, p. 243.

[38] Standish Motte, Outline of a system of legislation for securing protection to the Aboriginal inhabitants of all countries colonized by Great Britain; extending to them political and social rights, ameliorating their condition, and promoting their civilization, John Murray, London, 1840.

[39] J Campbell and Thomas Wilde to Lord John Russell, 27 July 1840, in Historical records of Australia. Series 1, vol. XX, p. 756; MF Christie, Aborigines in Colonial Victoria 1835-86, Sydney University Press, 1979, p. 115.

[40] ibid.

[41] 3 Vict., no.16; Sir George Gipps to Marquess of Normanby, 14 October 1839, in Cannon, Aborigines and Protectors, 1838-1839, pp. 760-61.

[42] A ‘future state’ is most likely a reference to life after death. WW Burton to Henry Labouchere, 17 August 1839, in ibid., p. 759; Historical records of Australia. Series 1, vol. XX, pp. 302-5.

[43] Sir George Gipps to Marquess of Normanby, 14 October 1839, in ibid., p. 368.

[44] J Campbell and Thomas Wilde to Lord John Russell, 27 July 1840, in ibid., p. 756.

[45] Bruce Kercher, An unruly child: a history of law in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1995, p. 16.

[46] AGL Shaw, A history of the Port Phillip District: Victoria Before Separation, Melbourne University Press, 2003, p. 137.

[47] As quoted by Kercher, An unruly child: a history of law in Australia, p. 16.

[48] ‘Aborigines’ Evidence Bill’, The Maitland Mercury, 29 June 1844, p. 2.

[49] ‘An Act to authorize the Legislatures of certain of Her Majesty’s Colonies to pass Laws for the admission in certain cases of unsworn testimony in Civil and Criminal proceedings’, 6 Vict., ch. 22.

[50] Kercher, An unruly child: a history of law in Australia, p. 17.

[51] E Deas Thomson to Sir James Dowling, 4 January 1842, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 144.

[52] Sir George Gipps to Lord Stanley, 24 January 1842, in ibid., p. 143.

[53] James Dowling to Sir George Gipps, 8 January 1842, in ibid., p. 145.

[54] Alex Castles, Australian legal history, The Law Book Company, Sydney, 1982, p. 526.

[55] Lord Stanley to Sir George Gipps, 2 July 1842, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 156.

[56] John Hookey, ‘Settlement and sovereignty’, in Peter Hanks and Bryan Keon-Cohen (eds), Aborigines and the law: essays in memory of Elizabeth Eggleston, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1984, p. 5; Susanne Davies, ‘Aborigines, murder and the criminal law in early Port Phillip, 1841-1851’, Historical Studies, vol. 22, no. 88, April 1987, p. 328.

[57] Hookey, ‘Settlement and sovereignty’, p. 5.

[58] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 28 August 1841, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 134.

[59] GA Robinson to CJ La Trobe, 11 December 1841, in ibid., p. 169.

[60] Shaw, A history of the Port Phillip District, pp. 135, 138; Barry Patton, ‘“Unequal Justice”: colonial law and the Shooting of Jim Crow’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 5, September 2006.

[61] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 28 August 1841, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 134.

[62] Shaw, Gipps–La Trobe Correspondence, pp. 150, 335.

[63] CJ La Trobe to the Gentlemen signing a representation without date, to His Honour the Superintendent, received by the hands of Dr Kilgour, 26 March 1842, in Copies or extracts from the despatches of the governors of the Australian Colonies, p. 215.

[64] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 4 July 1846, PROV, VPRS 16/P0, Unit 16, Item 46/598.

[65] Sir Charles Fitzroy to WE Gladstone, 25 October 1846, in Historical records of Australia. Series 1, vol. XXV, The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, Canberra, 1925, p. 230.

[66] Earl Grey to Sir Charles Fitzroy, 25 June 1847, in ibid., p. 632.

[67] ibid.

[68] Earl Grey to Sir Charles Fitzroy, 11 February 1848, in New South Wales, Legislative Council, Report from the Select Committee on the Aborigines and Protectorate, Government Printing Office, Sydney, 1849, p. 3.

[69] Castles, Australian legal history, p. 534.

[70] CJ La Trobe to Colonial Secretary, 18 November 1848, Report from the Select Committee on the Aborigines and Protectorate, p. 6.

[71] ibid.

[72] Castles, Australian legal history, p. 515.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples