Last updated:

‘“Woods Point is my dwelling place …”: Interpreting a family heirloom’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 8, 2009. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Louise Blake.

‘Margaret Knopp is my name, Victoria is my nation, Woods Point is my dwelling place and Heaven is my expectation’. This verse is one of many handwritten into a scrapbook that my great-grandmother, Margaret Hester (née Knopp) began compiling in 1884 in Woods Point, a goldmining township in the ranges east of Melbourne. Margaret was born on 25 July 1870 in Woods Point, and was the daughter of German miner Johann (John) Knopp and his Irish wife Catherine Foley.

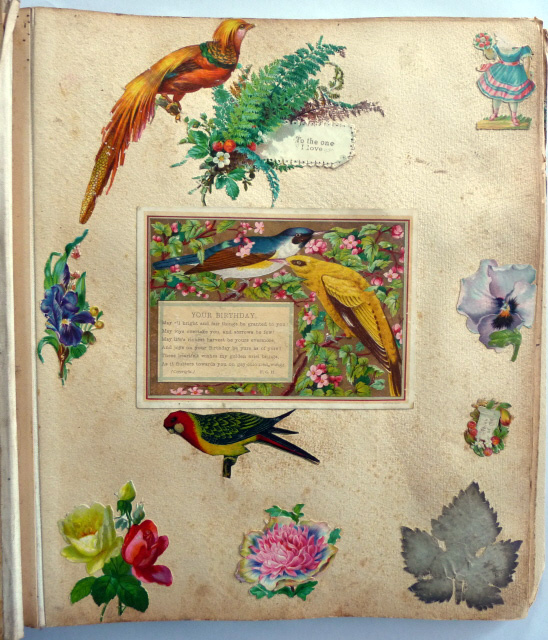

Several years ago I was given custody of this scrapbook together with some photographs and newspaper clippings, that had been in my father’s family for several generations. On first glance the scrapbook had some visual appeal – beautiful cards featuring flowers, Christmas scenes and handwritten verse – but little biographical or family information, or so I thought.

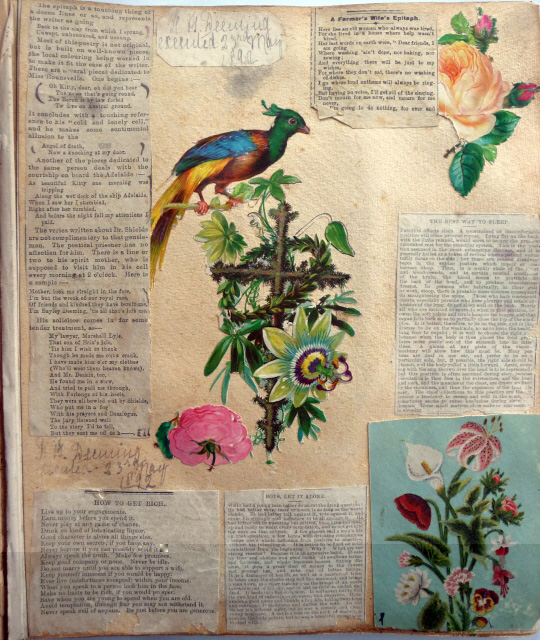

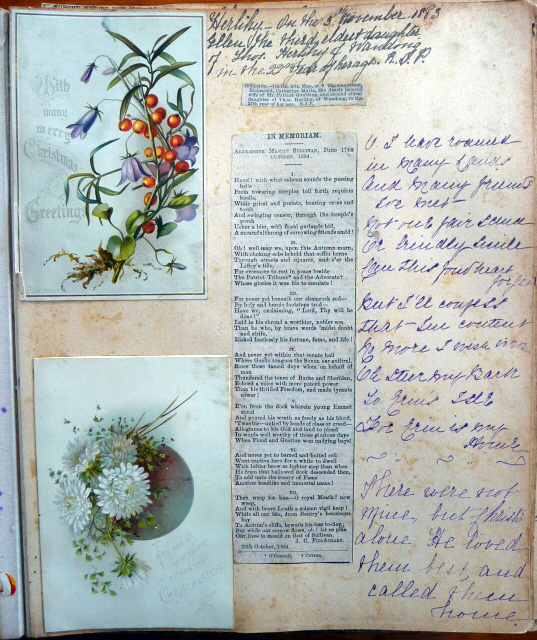

When I looked at the scrapbook recently in order to take digital photographs of the pages, I found several items that puzzled me. On a page surrounded by scraps of flowers and birds Margaret had written ‘F B Deeming executed 23rd May 1892’, not once but twice. Alongside the record of Deeming’s execution was an unsourced newspaper clipping that referred to poetry about the Deeming case. I would have paid little attention to these items had I not been familiar with Public Record Office Victoria’s online exhibition on Frederick Bailey Deeming – the murderer, bigamist, thief and conman who had been executed in Melbourne on 23 May 1892. Margaret’s record of the event was an odd inclusion amongst the romantic poetry and religious verse. The other items that caught my attention were two verses, handwritten by Margaret but with the name ‘Thos Herlihy’ given as the author. The first verse laments the passing of Thomas’s friend John Foley with whom he immigrated in 1857; the second records the deaths of several of Thomas’s female relatives. On another page Margaret had included the death notices of two of Thomas’s daughters. I was not familiar with the Herlihy name in Margaret’s family history, but clearly the family meant something to Margaret. It seemed there was more to this scrapbook than the romantic fantasies of a 14-year-old girl.

The discovery of Margaret’s scrapbook and its intriguing contents led me to revisit what I knew of Margaret’s family history and her ‘dwelling place’ of Woods Point. What transpired is an investigation typical of many family historians. Using the private records our ancestors have left behind and the public record of their lives in archives such as PROV we can build up a better picture of the life and times of individuals and families who made Victoria their home.

Woods Point in the 1860s and 1870s

Margaret Knopp’s scrapbook begins in the mid-1880s, but her family had been in the area since the initial gold rush of the 1860s.[1] With few direct references in the scrapbook to Woods Point or Margaret’s family history, it was necessary to revisit genealogical records, public archives, and the published histories of the region to learn more about the place where Margaret was born.

Adventurous prospectors along the Goulburn River discovered the Woods Point goldfield in the early 1860s. By August 1861 a small collection of huts and stores had been established to cater for the prospectors working the newly discovered reefs. The steep terrain made access difficult – the only way in was on foot or with a packhorse – but that didn’t stop keen prospectors descending on the district hoping to make their fortune.

Margaret’s father, John Knopp, and his older brother Peter were among the prospectors who arrived in Woods Point in the 1860s. The two men were born near the town of Nassau (then part of Prussia) and were the sons of farming couple Johann Knopp and Eva Kune. Leaving their homeland they travelled from Hamburg on the Magdalena and landed in Melbourne on 17 July 1860. The passenger list held at PROV reveals that most of their fellow passengers were single men aged in their 20s and 30s, some no doubt headed to the Victorian goldfields.[2] The Woods Point goldfield had not yet opened up when John and Peter arrived in Melbourne, so their initial destination is unknown. Perhaps they tried their luck at other goldfields before following the movement of miners to Woods Point. What is clear is that they were settled in Woods Point by 1864, when Peter died on 15 January after a short illness.

Eighteen months later John Knopp was recorded in the rate book of the newly formed Borough of Woods Point, but he did not remain long in the township itself.[3] New reefs had been found near Black River, east of Woods Point in December 1864 and by early 1865 numerous claims had been pegged out. Mining surveyor Alfred B Ainsworth visited the area in January and named the creek where many of the claims were situated Standers Creek.[4] Four mines were eventually established in the area – Royal Standard, Champion, Robert Burns, and Leviathan. John was one of the miners who joined this rush to Black River and was later associated with the Leviathan.

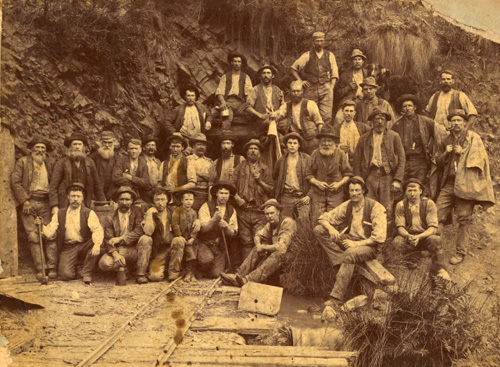

Author’s collection.

Author’s collection. These two photographs were part of a collection of family photographs that were passed on to me with the scrapbook. Both locations are unknown, though they are likely to be either around Woods Point or Bendigo.

Just how John Knopp fared in his early years at Black River is unknown, but he was not on his own for long. Some time prior to 1868 he met Catherine Foley, an Irish girl from County Kerry who had also arrived in Victoria in the 1860s. The couple married in January 1868 and remained in the area for a number of years. The total number of women and children in the community is unknown, though Bailliere’s Victorian Directory for 1868 lists 36 men at Black River, mostly miners with three storekeepers, one baker, and one blacksmith.[7] The settlement of Gooleys Creek, between Black River and Woods Point was slightly larger, and included two publicans and two violinists amongst the miners and traders.[8]

The winters were harsh and it is not surprising that of the six children Catherine gave birth to, only two survived infancy – three girls and a boy died. My great-grandmother Margaret was born at Royal Standard on 25 July 1870, but her birth was not registered until almost a year later, not by her parents, but by a neighbour from Black River. Margaret’s brother, John Patrick was born at Gooleys Creek on 14 May 1873 and a friend registered the birth some months later. Catherine’s experience of childbirth and motherhood was not unusual among the women living in the area. JG Rogers has noted that of the almost 300 people that were buried in Woods Point Cemetery between 1863 and 1880, more than half were infants, with the most infant deaths per year occurring between 1864 and 1868. Some infants were born prematurely or died soon after birth, while others died from conditions such as bronchitis, pneumonia or pleurisy, croup and whooping cough.[9] Living conditions, lack of medical knowledge and the difficulties in accessing medical help contributed to the infant mortality rate.

The Knopp family remained at Black River until approximately 1880, when John appears on the rate books as the owner of a cottage and garden in Miller Street, Woods Point.[10] John also maintained a hut at Black River where he worked the Leviathan mine, but his movements between the two are not known.[11] With the decline in the mining industry many of the mining townships did not last, and it is likely that the family – Catherine and the two children at least – moved to Woods Point to be closer to ‘civilisation’. Woods Point remained the family’s ‘dwelling place’ for the next twenty years and it was at this time that Margaret began compiling her scrapbook.

The scrapbook

The keeping of a scrapbook filled with decorative ‘scraps’ (‘multi-colored illustrations on embossed paper that were die-cut into shapes’),[12] greeting cards, newspaper clippings, and other printed ephemera was popular among women and children in the late nineteenth century. Research on some scrapbooks held in public collections suggests that they may have been compiled as craft projects to teach children how to ‘organize and classify information and to develop an artistic sense’ while others were put together to preserve personal or family history.[13]

Author’s collection.

Margaret was 14 years old when she began compiling her scrapbook, recording the date of October 1884 on the inside cover. Like the scrapbooks described above, it features a selection of greeting cards including Christmas cards, birthday cards, and a lace paper Valentine, some of which were published by well-known Belfast printing company Marcus Ward & Co. There are decorative scraps of birds, flowers and courting couples. Several postcards and a number of religious cards complete the selection. A number of pages feature the silhouettes of ferns and other leaves that Margaret may have collected around Woods Point, and there is even a dried bouquet of flowers pressed between two pages, a wedding bouquet perhaps. Some pages have had cards and other items removed. Was Margaret censoring her scrapbook in later years, or were the decorative cards removed and used elsewhere? Poetic verse, handwritten and cut from newspapers or journals, suggests that Margaret was educated, and indeed had an interest in poetry. Love and romance is one of the recurring themes and some poetry may have been written or transcribed during her courtship with her future husband, Charles William Hester. Clearly, Margaret could read and write and this led me to question what she was reading and what educational opportunities she and other children her age had in Woods Point.

Margaret’s education

Woods Point residents had access to books and reading material from the 1860s. Several local newspapers were published, sometimes in competition with one another, and newsagent S Collou & Co. advertised a delivery service between Woods Point and Black River, offering readers copies of the major daily newspapers, Government Gazette, books, stationery and overseas newspapers and periodicals.[14] Collou’s business also included a lending library and bookshop in Bridge Street. When Margaret began her scrapbook there was no locally published newspaper in Woods Point, leaving residents to rely upon the Jamieson & Woods Point Chronicle for their local news (which didn’t include much Woods Point news) until the Gippsland Miners Standard began in 1896. The latter at least was on Margaret’s reading list – news of her wedding was published in the paper on 28 September 1897 though the article is not included in her scrapbook.[15]

The only newspaper clipping in the scrapbook that identifies the region is an ‘Ode to Marysville’ written by ‘Poor Pat’ who was inspired by his stay at Keppel’s Hotel in Marysville in January 1885 to write this poem of thanks. The first verse reads:

O MARYSVILLE; sweet Marysville!

Bedecked with wood, bedewed with rill,

I fondly love thy ev’ry hill,

And though we part I’ll love thee still.[16]

Keppel’s Hotel was a popular destination in Marysville, one of many attractions destroyed in the bushfires that occurred on 7 February 2009. The ‘Ode’ is a poignant reminder of the beauty that drew visitors to the area, and is typical of the romantic nature of Margaret’s scrapbook.

Margaret did not preserve many contemporary news items. The exception to this is the page dealing with Frederick Deeming, which includes the date of his execution and a clipping referring to poetry about the case. The story of Deeming’s crime, trial and execution appeared in many newspapers, including the Jamieson Chronicle and Margaret could have read about the story in this paper or others. The question of why she includes it is more puzzling. The clipping appears to be a critique of poetry about the case. In one section the writer states that ‘most of this poetry is not original, but is built on well-known pieces, the local colouring being worked in to make it fit the case of the writer’.[17] Read in context with the other poetry and newspaper clippings included in her scrapbook, the Deeming references may form part of the educational purpose of the scrapbook — learning how to organise and classify information.

Reading newspapers wasn’t Margaret’s only means of education. The first schools in Woods Point opened in the mid-1860s, one of which was run by the Catholic Church. When the Catholic school closed due to a decline in numbers, Woods Point State School No 789 became the only school in the township. A search of the school correspondence files held by PROV has so far failed to find a list of pupils or other evidence that Margaret attended the school but it seems likely that she did. The correspondence between the school and the Education Department provides little information on what the children were taught, but it does paint a picture of what the experience may have been like for the teachers. And in the absence of any local newspapers for the period, the correspondence is also a valuable source of information on the Woods Point community.

Looking at the period from the late 1870s through to the 1880s, the Education Department had difficulties recruiting and keeping teachers at Woods Point. The most common complaints were the harsh winters, the isolation, and the higher cost of living. In January 1879 Assistant Teacher Mary Boyce wrote to the Department requesting a transfer:

It is unfair to a teacher to be left in a place like the above for any length of time, as, although the salary is not greater, the expense of every thing here is considerable, and that of travelling excessive. There are no advantages of any kind whatever being figuratively buried alive. My predecessor remained here only five months, therefore, as I have been here a year, I sincerely trust that you will give me hopes of removal before the winter sets in.[18]

The Department replied that Mary would be transferred as soon as a suitable opportunity arose but she was still at the school in December. John Lucas, Head Teacher at the time was similarly disenchanted when he wrote to the Department in March 1879 asking to be removed ‘from this fearful place’ so that he could be ‘nearer to the haunts of civilization’.[19] After a period of relative stability in the early 1880s under Head Teacher William Loughrey, who taught at the school with his wife Kate, there was another high turnover after the Loughreys departed, with many teachers reluctant to move to such an isolated community. The correspondence also reveals conflict over travel expenses between the Department and one of Loughrey’s replacements. Relief teacher Ebenezer Alexander hired a buggy at a cost of four pounds when he transferred from Jamieson to Woods Point, attracting the attention of Inspector Eddy. Eddy wrote that though he had been informed that the cost of buggy hire had increased due to the poor conditions on the road,

in my opinion the H. T. had no business to hire buggies on this occasion as he must have known well the dearness of travelling by such means, but rather that he should have hired a horse & ridden the journey & have had his effects brought down by a wagon.[20]

Author’s collection.

The conditions experienced by teachers at Woods Point were no different to those experienced by teachers in other remote communities, and no doubt the residents suffered similar feelings of isolation, particularly in winter.[21]

One of the teachers who lasted longer than some was Marion Miller, who commenced as a pupil teacher in 1879 at the age of 14. Marion, or Minnie as she referred to herself at the time, had at least one advantage over her transient colleagues in that she was born in Woods Point and lived there with her family. Marion’s father James Miller was a Councillor with the Borough of Woods Point and had a store and drapery in Bridge Street that sold boots, shoes, groceries, wines, spirits and ironmongery.

Marion became of interest to me when I read about her love of poetry and Irish literature, and her later career as a writer. According to Patrick Morgan, Marion drew inspiration from Irish literature and the Catholic Church, wrote about the virtues of Victoria’s mountains and forests, and based her first novel – the romance Barbara Halliday – on her childhood in Woods Point.[22] The themes Marion wrote about are the same themes that appear in Margaret’s scrapbook. Given that at one stage the two families were neighbours and that Marion taught at the school when Margaret began her scrapbook, it is possible that the two were known to one another. Marion was five years older than Margaret: was she an influence on the composition of Margaret’s scrapbook, or were romance, Catholicism and the natural world of interest to many young women living in Woods Point at the time? Their mutual interest in Irish heritage (both of Marion’s parents were Irish; Margaret’s mother was Irish) is reflected in Marion’s later writings and the Irish references in Margaret’s scrapbook.

Margaret’s Irish heritage

Woods Point was a township of migrants and the Irish were well represented – in the population and in the names given to settlements, hotels, mines and reefs. Margaret’s mother Catherine Foley was born in County Kerry and arrived in Woods Point in the mid-1860s, though little else is known about her arrival and family connections. Catherine may have been one of many single Irish women who immigrated to Victoria and found work as domestic servants. In Woods Point she would have been surrounded by familiar accents from her native Kerry and elsewhere in Ireland.

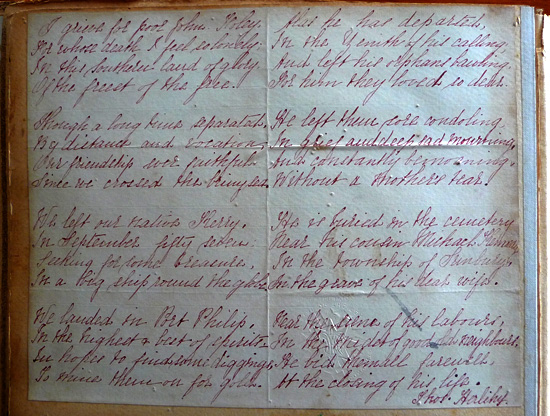

As I stated in the introduction, among the references in Margaret’s scrapbook that interested me were the two poems or songs written by Thomas Herlihy. One was a lament for his friend John Foley with whom he immigrated in 1857. The first half of the poem reads,

I grieve for poor John Foley

For whose death I feel so lonely

In this southern land of glory

Of the freest of the free.Though a long time separated

By distance and vocations,

Our friendship ever faithful

Since we crossed the Shiny seaWe left our native Kerry

In September fifty seven

Seeking for some treasure

In a big ship round the globeWe landed in Port Phillip

In the highest & best of spirits

In hopes to find some diggings,

To mine them on for gold[23]

After locating the Herlihy family – and John Foley – on the passenger list for the ‘British Trident’ which arrived in Victoria in December 1857, my initial research focused on finding a connection between John Foley and Margaret’s mother Catherine.[24] Though John Foley died the same year that Margaret began the scrapbook, I could find no direct link with Catherine. I then focused my research on Thomas Herlihy and soon found a connection.

Author’s collection.

A few years after arriving in Victoria in 1857, Thomas was a storekeeper at Gooleys Creek, a settlement south east of Woods Point where Irishman William Gooley had found gold in May 1861.[25] By 1865-66 several mines were established in the area, including the Shamrock and Never Mind. The Irish presence at Gooleys Creek no doubt inspired the names of several other mining companies – including the Erin GM Co. and the Rose, Thistle and Shamrock GM Co. – though according to Brian Lloyd both companies failed.[26] Thomas’s wife Catherine gave birth to three of their 13 children in Gooleys Creek, but in October 1865 their son Daniel died three days after he was born. When I looked at the inquest file on Daniel’s death I found that one of the witnesses at the inquest was a Catherine Foley. Catherine stated that she had been ‘with Mrs Herlihy from the birth of her child until his death.’[27] Though there was more than one Foley family living in the region at the time it is likely that this Catherine was Margaret’s mother, a friend or acquaintance of the family, thus providing some explanation for the connection between the two families.

Thomas and his family remained in Gooleys Creek until the early 1870s when many of the smaller mining townships disappeared as a result of the decline in the mining industry. They then moved to the Kilmore/Wandong district where they had a farm and Thomas worked for the Victorian Railways. According to one local history, the family was well known in the district.

Less formal entertainment was provided by the Herlihy family, who lived on a modest farm east of the railway reserve north of Wandong. A convenient square of ground was fenced and leveled and to it would come the townsfolk to dance by moonlight to the violin and accordion played by the Herlihy’s.[28]

Thomas’s position as Deputy Electoral Registrar for Kilmore, a position he was appointed to in 1885, no doubt contributed to the family’s profile in the district.[29]

Despite the Herlihys’ move to Wandong, Margaret’s family must have maintained some contact and interest in their welfare, as Margaret recorded the deaths of two of Thomas’s daughters – Ellen in 1883, Catherine in 1886 – in her scrapbook. Of interest on the same page is a poem in memory of Alexander Martin Sullivan, an Irish politician, lawyer and journalist who died on 17 October 1884.[30] Sullivan’s notable career included the editing and ownership (with his brother, Timothy Daniel) of the Irish nationalist newspaper The Nation, as well as other writings. It is not clear if Margaret or her family read The Nation, but at least one newspaper clipping she included reprinted a poem by Timothy that first appeared in The Nation.[31]

Author’s collection.

These references are just some of the inclusions that suggest Margaret’s Irish heritage was important to her, and gives some insight into the bonds that existed amongst the Irish community in Woods Point.

Leaving Woods Point

Margaret’s ties to Woods Point began to unravel after the death of her father in 1895. Her brother John sold the Leviathan mine to the owners of the Hope and Sir John Franklin mines, and in 1897 she married Charles William Hester, a miner from Bendigo living in Woods Point. The couple lived in the suburb of Piccadilly where three of their seven children were born, including my grandmother Catherine. Lloyd writes that the mining industry around Woods Point ‘was in the doldrums’ at the turn of the century and would not pick up for almost two decades.[32] This is perhaps what prompted the family to leave Woods Point around 1903, following Margaret’s mother and brother who had moved to Gisborne a year or two earlier.

Private collection.

With the move to Gisborne a new chapter in Margaret’s life began, but she still maintained some connection with her Woods Point childhood by keeping the scrapbook. Later additions are difficult to date, though a New Year card sent to ‘Uncle Charlie’ (Margaret’s husband) from Mary (daughter of Charles’s sister, Elizabeth Marchesi) in either 1905 or 1909 suggests that she – or other members of the family – may have added to it. The scrapbook was later passed down through Margaret’s female descendants – her daughter Catherine, her granddaughter Margaret, and two great-granddaughters, of whom I am one. It was not the only family heirloom that she passed on, but it is perhaps the one that gives the clearest insight into Margaret’s formative years and the place she called home. Without the information gathered from public records and published sources, the scrapbook may have remained simply a decorative family heirloom, but together with this research the scrapbook and the story of Margaret’s family becomes a small part of the history of Victoria’s goldfields.

Endnotes

[1] My thanks to Maureen Hester who did the initial research into the Knopp family that formed the basis of my research. Thanks also to the women in my family who have treasured the scrapbook and contributed to its history.

[2] PROV, VPRS 7667, Microfiche copy of Inward Overseas Passenger Lists (Foreign Ports) 1852-1923, fiche 73, p. 1, Magdalena.

[3] PROV, VPRS 11458/P1, Unit 1, Borough of Woods Point Rate Book, 1865.

[4] AB Ainsworth, ‘The Black River Rush’, The Argus, 6 February 1865.

[5] Letter to Minister of Mines and Survey, PROV, VPRS 1277/P0, Unit 1, Minute Book of Borough of Woods Point, 4 August 1865.

[6] Anne & Robin Bailey, The Windy Morn of Matlock: the history of a Victorian mountain goldfield, Mountain Home Press, Melbourne, 1998, p. 109.

[7] ‘Black River’, The Official Post Office directory of Victoria (Bailliere’s), FF Bailliere, Melbourne, 1868.

[8] ‘Gooleys Creek’, in ibid.

[9] JG Rogers, Woods Point Cemetery and transcription: burials 1863-1920s, JG Rogers, Moe, 1995, pp. 110-15.

[10] PROV, VPRS 11458/P1, Unit 1, Rate Book, 1880.

[11] PROV, VPRS 11452/P1, Unit 4, Rate Book, 1888.

[12] Ellen Gatrell, ‘More About Scrapbooks’, available at <http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/eaa/scrapbooks.html>, accessed 24 March 2009.

[13] ibid.

[14] Woods Point Times & Mountaineer, 12 February 1867.

[15] Gippsland Miners Standard, 28 September 1897.

[16] ‘Poor Pat’, ‘Ode to Marysville’, 5 January 1885, unsourced newspaper clipping in scrapbook.

[17] Unsourced newspaper clipping in scrapbook.

[18] Mary Boyle to Secretary for Education, PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Unit 434, File 79/1883, 17 January 1879.

[19] John P Lucas to Secretary for Education, PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Unit 434, File 79/11541, 31 March 1879.

[20] Inspector Eddy to Secretary for Education, PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Unit 435, File 87/19126, 19 September 1887.

[21] See Peter Davies, ‘A lonely, narrow valley: teaching at an Otways outpost’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, No. 7, September 2008.

[22] Patrick Morgan, ‘Marion Miller Knowles: novelist and poet’, Táin, November-December 2000, p. 23.

[23] Thomas Herlihy, undated handwritten poem in scrapbook.

[24] PROV, VPRS 7666, Microfiche copy of Inward Overseas Passenger Lists (British Ports) 1852-1923, fiche 137, p. 6, British Trident, December 1857.

[25] ‘Gooleys Creek’, The Official Post Office directory of Victoria (Bailliere’s).

[26] Brian Lloyd, Gold in the Ranges: Jamieson to Woods Point, Histec Publications, Brighton East, 2002, p. 42.

[27] PROV, VPRS 24/P0>, Unit 162, File 1865/927, Daniel Herlihy.

[28] JW Payne, Pretty Sally’s Hill: a history of Wallan, Wandong and Bylands, Lowden Publishing, Kilmore, 1981, p. 68.

[29] Victoria Government Gazette, no. 95, Friday 9 October 1885, p. 2811.

[30] William Grattan-Flood, ‘Alexander Martin Sullivan’, The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 14, Robert Appleton Company, New York, 1912, available at <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14329a.htm>, accessed 29 March 2009.

[31] TD Sullivan, ‘The Robin’s Song’, Nation, reprinted in an unsourced newspaper.

[32] Lloyd, p. 159.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples