Last updated:

‘Little Latrobe Street and the Historical Significance of Melbourne’s Laneways’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 10, 2011. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Fiona Poulton.

The narrow laneways that wind their way throughout Melbourne’s CBD have become icons of the city’s rich culture and history. But how did laneways appear in the city in the first place and what can they tell us about its past? Using PROV’s extensive collection of rate books, Sands and McDougall directories and building applications, this article examines the history and heritage of Melbourne’s ‘little’ streets through an in-depth study of one particular inner-city laneway. Little Latrobe Street was not included in the original city grid, but appeared in 1851 during the Victorian gold rush population boom. The article examines what remains of Little Latrobe Street’s history today and argues that Melbourne’s laneways are a unique feature of the city and deserving of heritage protection.

European pastoralists in search of good farming land began a settlement on the banks of the Yarra River in 1835. However, the city of Melbourne only really began to take shape in 1837, when a rectangular grid designed by surveyor Robert Hoddle was laid out alongside the Yarra. Hoddle designed the streets to be 99 feet (30.2 m) wide, rather than the usual 66 feet (1 chain, or 20.1 m), though Governor Bourke insisted that smaller streets be situated in between the main thoroughfares to allow for entrances to buildings from the rear.[1]

With some sort of order established upon the settlement by the grid, the first sales of Crown land, authorised by Governor Bourke, also began in 1837. As the city developed, allotments of land originally purchased from the Crown were subdivided and re-subdivided many times. With these subdivisions came the need for an increasing number of smaller streets, or laneways, providing access to the back of properties fronting the larger streets. The sense of order that had been imposed on the land by Hoddle’s grid soon disappeared, with lanes and alleys winding in every direction through the city blocks. During its early years, Melbourne was occupied mostly by dwellings and small businesses, with laneways providing rear service access for servants and carts carrying goods.

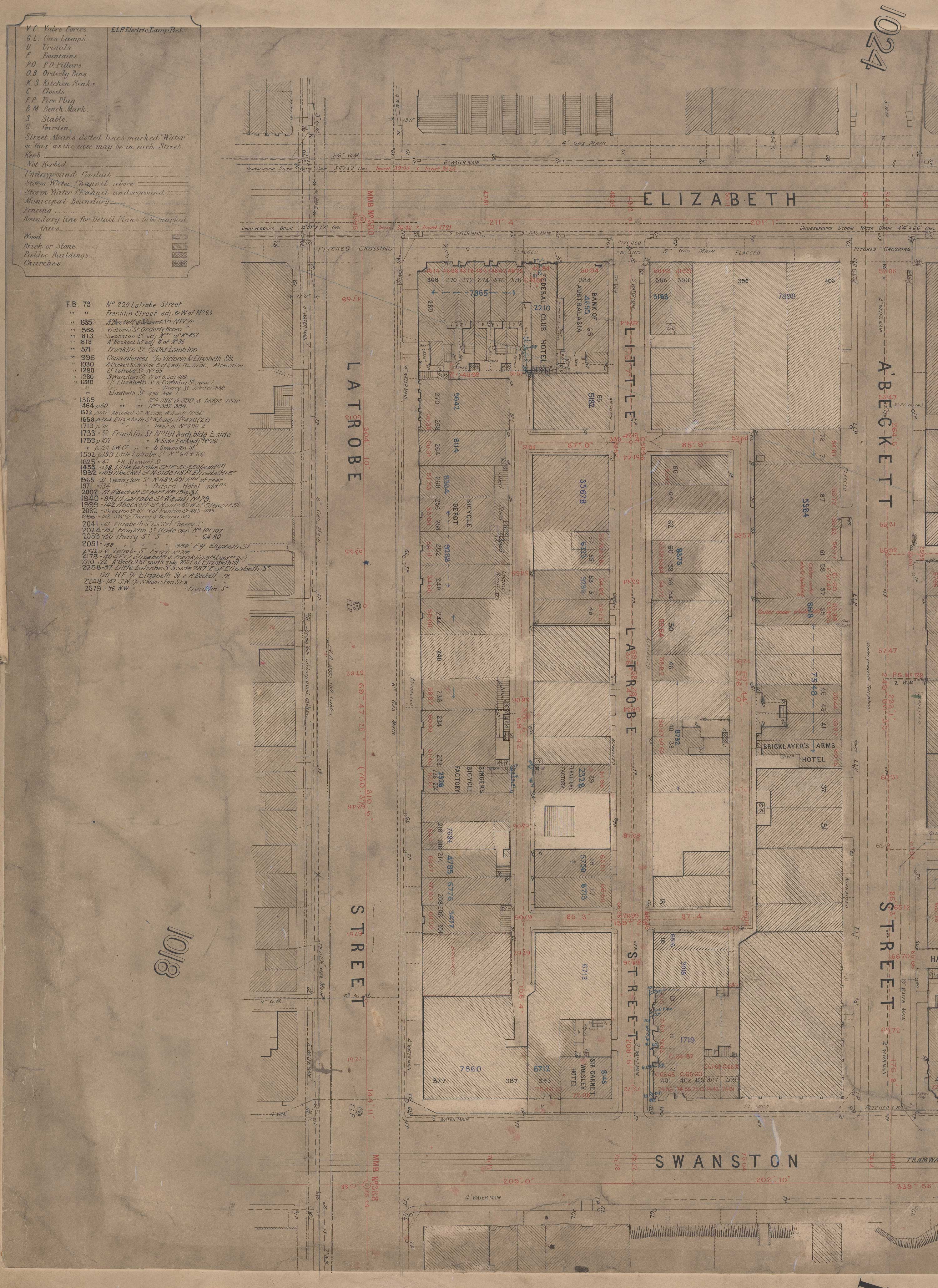

Little Latrobe Street is one such laneway, running east to west between Swanston and Elizabeth streets and located in the centre of the block bordered by Latrobe and A’Beckett streets at the northern end of the CBD. It is situated within what was originally known as Section 37 of the Parish of Melbourne North (see directly below), County of Bourke, which comprised the entire block bordered by Elizabeth, Swanston, Latrobe and A’Beckett streets. Of Melbourne’s multitude of laneways, Little Latrobe Street makes a particularly interesting case study. Curiously, it traverses the length of just one city block, rather than running the length of the CBD like the main thoroughfares and other ‘little’ streets laid out by Hoddle in the 1830s – Little Lonsdale, Little Bourke, Little Collins and Flinders Lane. Moreover, while Section 37 with its twenty Crown allotments clearly appears on the original parish map, Little Latrobe Street itself is not shown. The street does appear on the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) detailed base plan for Melbourne North (see below next paragraph), which is undated.

As the settlement of Melbourne grew, so too did the need for a system to regulate its residents, and on 22 October 1841 an Act of Parliament divided the settlement into four wards – Bourke, Latrobe, Gipps and Lonsdale. For rate-paying purposes, Little Latrobe Street fell within the north-east section of Melbourne in the Ward of Gipps, though it is not recorded in the rate books for that ward until 1851.[2] It appears, therefore, that the street did not exist when the original parish map, which is undated, was drawn up. Rather, it was added some time between 1850 and 1851, through the centre of Section 37. This means that Little Latrobe Street was not included in the original 1837 layout of the city’s grid with the other ‘little’ streets, but developed much later. It is significant that Little Latrobe Street was constructed around 1850, as there was a huge influx of immigrants into Melbourne at that time following the discovery of gold in Victoria and, clearly, more space was needed to cope with the rising population. Little Latrobe Street thus came to exist in a much more ‘natural’ way than the streets of the grid, developing as the city itself was growing, out of a need rather than a structured plan.

While Little Latrobe Street did not exist until 1850-51, it is still possible to discern information about the allotments within which it was situated from the undated map of the Parish of Melbourne North. According to this pre-1851 record, almost all of the land in Section 37 – indeed, eighteen of the twenty Crown allotments – were purchased by Albert Thoume Ozanne and Thomas Budds Payne on 8 November 1849. In addition, the MMBW plan shows that many properties clearly backed onto alleyways, which were situated on both the north and south sides of the street, providing access to the rear of properties not only in Little Latrobe Street, but also the surrounding larger thoroughfares of Latrobe Street and A’Beckett Street.

Case Study: 22-32 Little Latrobe Street

The rate books for the Ward of Gipps provide further insight into the built structures and their occupants on Little Latrobe Street as well as the history of land use over time. The Sands and McDougall street directories give similar insight into how land was being used in areas of Melbourne, listing residents and their occupations.[3] An examination of the rate books for the Ward of Gipps and the Sands and McDougall directories for Little Latrobe Street was undertaken, beginning with the appearance of the street in the rate books of 1851. It is important to note that street numbers were only recorded in rate books in an ad hoc manner until the late 1860s. In addition, owners were sometimes listed rather than occupants. The information that could be gathered from these sources is therefore incomplete and contains some gaps.

The Table below presents the history of built structures and occupation at one particular site – 22-32 Little Latrobe Street – at five-yearly intervals and reflects the general pattern of development in the street as indicated by the rate books and the Sands and McDougall directories. The Table begins in 1865 as this was the first year that street numbers were listed with some consistency. Where there is no information listed in the Table, there was no entry in the rate book or directory.

| STREET NUMBERS | ||||||

| YEAR | 22 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 |

| 1865 | ||||||

| Occupant | James McNamara, saddler | Charles Long | Louis Kolling | John Wheelhouse | ||

| Owner | James Flanagan | Agent | Agent | Mr Ledgeworth | ||

| Built Structures | 5-roomed brick house | 3-roomed brick house | 3-roomed brick house | |||

| 1870 | ||||||

| Occupant | Charles Merrick, boot factory (i) | |||||

| Owner | Jennings & Coote | |||||

| Built Structures | Shop & five rooms, brick | |||||

| 1875 | ||||||

| Occupant | James McNamara, collar maker | |||||

| Owner | ||||||

| Built Structures | ||||||

| 1880 | ||||||

| Occupant | James McNamara, collar maker | |||||

| Owner | ||||||

| Built Structures | 5-roomed brick house | |||||

| 1885 | ||||||

| Occupant | James McNamara, collar maker | Devon & Cornwall Hotel (ii) | ||||

| Owner | Samuel Bloor | |||||

| Built Structures | 6-roomed brick house | |||||

| 1890 | ||||||

| Occupant | Mrs Lilly Walker | Mrs Mary Ann Williams | Thomas Fitzpatrick | Mrs Elizabeth Musgrove | ||

| Owner | ||||||

| Built Structures | ||||||

| 1895 | ||||||

| Occupant | Mrs Rose Johnson | Vacant | Vacant | Ah Hay, cabinet maker (iii) | John and Annie Morris | |

| Owner | George Fyfe | Peter Fettling | George Fyfe | |||

| Built Structures | 5-roomed brick house | 4-roomed brick house | 3-roomed brick house | |||

| 1900 | ||||||

| Occupant | Arthur Nicoli | John Lawson (iv) | Low Shee | James and Florence Lee | ||

| Owner | George Fyfe | George Fyfe | George Fyfe | George Fyfe | ||

| Built Structures | 5-roomed brick house | 5-roomed brick house | 4-roomed brick house | 5-roomed brick house | ||

| 1905 | ||||||

| Occupant | Fan Gee | Wah Kee, cabinet maker | ‘Occupied by Chinese’ | Ah Young, cabinet maker | ||

| 1910 | ||||||

| Occupant | Fung Kee, cabinet maker | Sam Hing | Mung Hue | Mrs Maude Gay | ||

| 1915 | ||||||

| Occupant | Fung Kee, cabinet maker | Kee Dick | ‘Occupied by Italian hawkers’ | |||

| 1920 | ||||||

| Occupant | Yee Ack, cabinet maker | ‘Chinese’ | ‘Chinese’ | ‘Chinese’ | ‘Greek hawkers’ | |

| 1925 | ||||||

| Occupant | auto welders and engineers (18–22) | Walter Saunders, motor radiator works, repairs | Arthur Cowl, farrier | S. Reading & Son, die sinkers and engravers | ||

| 1936 | ||||||

| Occupant | R. A. Johnson, motor engineer | |||||

| 1937 | ||||||

| Occupant | J. G. Schultz, motor engineer | |||||

| 1944/45 | ||||||

| Occupant | ‘Motor Park’ | |||||

i. There is a discrepancy here between the rate books and the Sands and McDougall directories, which list Terence Flood as the occupant.

ii. This hotel is not listed again at this address, but is often listed as number 50 or 52 Little Latrobe Street.

iii. This information is from the rate books, although Sands and McDougall list number 30 as vacant in 1895.

iv. This occupant is from the rate books; William Todd is listed as the occupant in Sands and McDougall.

The Table indicates that from the time Little Latrobe Street was constructed, some time in 1850, it was occupied mostly by small businesses, such as James McNamara the collar maker, and was made up predominantly of small brick buildings. The sources reveal that McNamara ran his business for more than thirty years out of five- and six-room brick houses. He is listed at number 18 in 1865 and subsequently at number 22, and then from 1890 at number 46 until he disappears from the records in 1900. Sands and McDougall list the Devon and Cornwall Hotel in the street from 1870 and in 1885 it is listed at number 24. However this is likely to be either a mistake or an issue with street numbering, as the hotel appears thereafter at number 50-52 until its closure between 1905 and 1910. The Devon and Cornwall Hotel was thus a major presence in Little Latrobe Street for over thirty-five years, occupying a fourteen-room brick building. Perhaps the hard-working inhabitants of the small businesses surrounding the hotel would drop in for a beer after work.

By the early twentieth century the area was becoming more industrial, with cabinet makers and hawkers occupying several properties. The Table clearly demonstrates how the earlier small subdivisions were being combined into larger blocks for bigger industrial developments. The different occupants and small brick buildings at 22, 24, 26, 28, 30 and 32 Little Latrobe Street had by 1936 become just the one address (22-32) with the one occupant. Although very little information was found regarding the use of 22-32 Little Latrobe Street between 1926 and 1934, this industrial development continued into the 1920s, as in 1925 there were auto welders and engineers installed at number 22 Little Latrobe Street, motor radiator works and repairs at number 26 and die sinkers and engravers S Reading & Son at number 32.

Occupation and Land Use of Little Latrobe Street

The case study above is highly representative of the historical development of Little Latrobe Street as a whole. In the earliest street directory, compiled by Sands and Kenny in 1857, Little Latrobe Street was filled with small businesses, including blacksmiths, plumbers, clothing manufacturers and food merchants. Women were also running businesses, with a laundress at number 21 and a dressmaker at number 9. The rate books reveal that these businesses were almost all housed in brick buildings of two or three rooms, though in 1855 four wooden houses were listed and from 1860 the records begin to include sheds and stables on many properties.[4]

What the case study does not show is that in the booming economic and social environment of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ in the 1880s, larger industries began to develop in Little Latrobe Street, with Corris, Craig & Co. boot factory and The Pearl Cold Water Soap Manufacturing Co. appearing amongst the small-scale basket manufacturers and blacksmiths. Then, throughout the 1890s there is an increase in the number of vacant properties in Little Latrobe Street, with seventeen properties listed as vacant in the street directory of 1895. This increase supports Robyn Annear’s description of the many buildings in the inner city abandoned during the terrible economic depression of that time. Many of those buildings ended up as jobs for Whelan the Wrecker, who, conversely, enjoyed a decade of strong economic growth with so many abandoned buildings around for the wrecking business.[5]

Historian Weston Bate has described the laneways of the north-eastern quarter of Melbourne’s CBD in the decades following the 1890s economic depression as ‘havens for small manufacturers, builders and craftsmen’.[6] Little Latrobe Street was certainly one such laneway, filled with a wide variety of businesses including carpenters, plumbers, engineers, and manufacturers’ agents. Interestingly, the names of Chinese occupants begin to appear in the street from around 1900, many listed as cabinet makers. About the same time, the names of European immigrants also start to appear, such as Greek newspaper proprietor Efstratius Venlis, who occupied 54-56 Little Latrobe Street in 1915. A Chinese cabinet maker is listed at number 30 Little Latrobe Street from 1895, and the street directory reveals that by 1915 there were seventeen properties clearly occupied by immigrants, twelve of them Chinese and the remaining Greek and Italian. This appearance of Chinese cabinet makers in Little Latrobe Street reflects the expansion of Melbourne’s Chinatown a few blocks away in Little Bourke Street during the 1880s, as Chinese gold diggers who had first arrived during the 1850s gold rushes relocated to the city to find work and set up businesses. According to Morag Loh, the population of Chinese people in Melbourne more than doubled between 1881 and 1901.[7] The increase in immigration was clearly a difficult adjustment for some; foreign immigrants are often listed in Sands and McDougall simply as ‘Italian hawkers’, ‘Greek hawkers’ or ‘Chinese’.

Despite the fact that much of Melbourne’s industry had started to move out of the CBD to inner suburbs like Collingwood and Footscray, by the early twentieth century Little Latrobe Street was increasingly dominated by larger industries, with William Unsworth’s Gas Apparatus Works at number 58 and Coghlan and Tulloch’s Ballarat Brewing Co. at number 41. Some of the smaller businesses survived the development of bigger industries in the area and even began to expand themselves. Henry Triplett’s basket manufacturing business, for instance, is listed in the street directories continuously at number 2A and then 19 Little Latrobe Street from 1875 to 1955. The building occupied by Triplett is listed as a three-room brick house in the rate books of 1875, which by 1880 had become four rooms. At the same time as the street directory indicates Triplett’s business expanding to 19-27 Little Latrobe Street in the 1890s, the rate books reveal that he then owned four properties, each with three- or four-room brick buildings erected on them. By 1900, Triplett’s property had become a ‘brick factory and store yard’ which was inherited by his three sons upon his death in 1909. It seems the basket manufacturing business continued to be run by the Triplett family until its disappearance from the records in 1955.[8]

The early twentieth century also saw the appearance of philanthropic organisations in Little Latrobe Street, reflecting the changing attitudes towards the poor and disadvantaged people of Melbourne. The city’s laneways had developed a reputation for being home to Melbourne’s slums – dark, dirty and unsavoury places filled with crime, homelessness and prostitution, particularly in Little Bourke and Little Lonsdale streets.[9] Poverty and overcrowding in such areas created unsanitary living conditions, which led to disease and general misery, turning the laneways into areas where respectable citizens dared not tread. Fergus Hume described the laneways in his 1880s novel The mystery of a hansom cab:

Kilsip and the barrister kept for safety in the middle of the alley, so that no one could spring upon them unaware, and they could see sometimes on the one side, a man cowering back into the black shadow, or on the other, a woman with disordered hair and bare bosom, leaning out of a window trying to get a breath of fresh air.[10]

Little Latrobe Street was certainly not such a dangerous, unpleasant place, as throughout its history it seems to have been occupied by respectable, albeit working-class, businesses and industries.[11] However, the history of Melbourne’s low-life in the city’s laneways is still a part of the area’s heritage. The Helping Hand Mission Society was the first of the philanthropic organisations in Little Latrobe Street, listed at number 29 in the rate books for 1905. The Salvation Army then took over the premises, listed in the rate books of 1910 as ‘Salvation Army Elevator’. An Elevator, according to Salvation Army founder William Booth, was ‘a combination of workshop, home and religious retreat’.[12] The unemployed, homeless, and those who had fallen on hard times through drink or crime would be given work at an Elevator in various trades such as carpentry, rag-sorting or baking. It is unclear what exact services were offered by the Elevator in Little Latrobe Street, though it certainly provided people with shelter as it was specifically referred to as a ‘lodginghouse’ in the rate books from 1920 onwards. By 1935, number 29 had fallen vacant after the Salvation Army had served the community from there for over twenty-five years.

As is evident in the Table above, by the 1930s businesses related to motor vehicles had come to dominate Little Latrobe Street, with motor engineers and accessory merchants lining the street. The first of these businesses appeared in 1905: The Acme Motor and Engineering Co. Pty Ltd, managed by Frank Bennett. By 1935 there were twelve businesses in the street to do with motor cars, including Nason and Pollard motor engineers at number 34 and WT Greenwell’s motor accessories store at number 51. These replaced declining businesses such as Hubert S McCausland’s, a coachbuilder at number 60, and shoeing forge Wincliffe and Co. at number 68. Such businesses had by 1935 disappeared from the records completely.There was even a school for teaching motor driving, which occupied number 65-69 for at least five years from 1925: Austin Motor School. The increasing use of the motor car had an enormous effect on the inner city, with cars lining the streets and laneways by the 1950s.

Little Latrobe Street Today

The Sands and McDougall street directories indicate that, with smaller businesses expanding and larger industries moving into Little Latrobe Street from the turn of the century, many of the small brick buildings that originally dominated the street were probably demolished at that time to make way for larger factories and warehouses. According to the Building Application Index held by PROV, factories were erected at number 12-14 Little Latrobe Street in 1928, number 16 in 1924, number 31-33 in 1919, number 35-39 in 1929, number 43-47 in 1924, and number 49, also in 1924.[13]

The Building Application Index also confirms that many of the buildings seen in the street today date from more recent times. It reveals, for example, that a two-storey brick building occupied by James McNamara, the collar maker in the 1890s at number 46 Little Latrobe Street, was demolished in 1986 and a three-storey ‘shop/office’ built in its place.[14] Today the building is an apartment block, surrounded by several other modern buildings that also appear to be apartments. Though many of Little Latrobe Street’s original buildings are now gone, signs of its history do remain. The alleyways running off the laneway on both sides are still being used, servicing both the buildings fronting Little Latrobe Street and buildings fronting Latrobe and A’Beckett streets. The sign on an RMIT University building in Little Latrobe Street demonstrates this continuing use. What is more, these cobblestoned alleys continue to provide out-of-the-way areas to store rubbish, just as they would have done 150 years ago.

Some buildings dating from the 1920s do still exist in Little Latrobe Street. One, which according to the Building Application Index was erected in 1928 and converted to a factory in 1938, then to a café in 1992, now houses a popular artists’ supplies store. Mark Thompson manufactured scientific instruments for over thirty years from the 1930s to the 1960s out of his 1924 factory at number 16. In the 1970s during the women’s liberation movement, this building housed the first Women’s Liberation Office where women gathered to discuss ideas and plan campaigns to fight for equal rights. Today it is occupied by a café popular with RMIT University students. Another old brick building is the premises of a used motorcycles store, indicating that traces do remain of Little Latrobe Street’s history as a centre for engineering and auto mechanics. Perhaps most importantly, despite the new modern buildings that now dominate the laneway, developments have at least been kept at a reasonable height and no more than four or five storeys high. Though Little Latrobe Street is today dwarfed by surrounding skyscrapers and large developments, it has so far retained its laneway feel.

Heritage Significance of Little Latrobe Street

The story of Little Latrobe Street is in many ways the story of Melbourne in microcosm. The laneway owes its very existence to the population boom during the 1850s gold rush. It tells of the inner workings of the early settlement and the lives of the often-forgotten working classes running small businesses from simple brick buildings hidden in the backstreets. The remains of the larger scale factories and industries that developed from the turn of the century speak of their importance to the growth of Melbourne as a global commercial city. Little Latrobe Street contains the stories of Chinese and European immigrants, whose influence on life in Melbourne transformed the cultural landscape of the city, and the stories of Melbourne’s philanthropic organisations, who recognised the plight of the poor and needy and worked to support them. The laneway has enormous historical and social significance and meets the requirements of the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter for the conservation and management of cultural heritage sites in at least these two categories.[15]

While Melbourne’s laneways were originally built simply for practicality, in more recent times concerted efforts have been made to revitalise them, and laneways have become a valued and even celebrated feature of the city. The City of Melbourne’s Laneway Commissions scheme, launched in 2001, has encouraged the use of laneways for temporary public art displays.[16] The laneways have thus become vessels for expressing the city’s twenty-first-century culture and identity, as well as its history. The smaller, hidden alleyways winding through the depths of the city blocks have become particularly popular amongst Melbourne’s artists and young people, inspiring the creation of the Laneway Music Festival in 2004. Laneways, including Little Latrobe Street, are also favourite sites amongst graffiti artists to create their constantly changing artworks.

There has been some thought as to how laneways can be developed in a way that is sensitive to their history. Landscape architect Fiona Harrisson has written about her design for the redevelopment of Little Latrobe Street in the late 1990s. By that time, Little Latrobe Street was made up of ‘an eclectic mix of industrial, commercial, and residential development’ and Harrisson’s aim was to emphasise the industrial heritage features still visible in the laneway. She did this by widening the footpath on one side only, so that pedestrians ‘walking on the widened side have an open view that takes in the old facades’ of the old brick factories and warehouses on the other side of the street.[17]

However, despite the burgeoning laneway culture and the renewed interest in Melbourne’s heritage sites, there is still a tendency to focus on the city’s impressive landmark heritage buildings, and to neglect those areas that perhaps are not as impressive but are still an important part of our history. Fortunately, the Melbourne Heritage Action Group, formed in July 2010, is increasingly advocating for the preservation of little-known and under-appreciated heritage buildings and locations in Melbourne’s CBD, including laneways and ‘hidden’ building interiors.[18] A debate over whether developers should be kept away from the city’s laneways is currently underway. However, this debate focuses on the financial benefit to Melbourne City Council of selling laneways to developers rather than on the heritage and cultural values of the lanes themselves.[19]

Weston Bate has described the phenomenon of laneways disappearing under large-scale developments once developers began to consolidate titles in the 1970s. The Melbourne Central shopping complex and Collins Place office and retail development each led to the destruction of four laneways.[20] These developments signified a major loss of the city’s heritage, but also a loss of pedestrian and service access systems, and of Melbourne’s rich diversity and character. As it is inevitable that Melbourne’s laneways will undergo further development in the future, it is crucial that the heritage values of those that remain are properly assessed and that appropriate regulations are put in place to ensure that such a loss does not continue to occur. A search of local planning schemes has found no heritage overlays on Little Latrobe Street. Fifteen properties in the laneway are listed on the Victorian Heritage Register, though no statement of significance is provided for any of these sites. Hopefully their very inclusion on the register means that any plans for development will be examined with great care.[21]

It is difficult to safeguard these heritage sites in the ever-changing and constantly evolving modern metropolis that is Melbourne today. While public awareness of heritage issues and interest in the potential uses of Melbourne’s laneways have grown in recent years and significantly lessened the chances of icons like Little Latrobe Street disappearing under large developments, it is still important that those charged with developing the city’s laneways are persuaded to make heritage issues a major consideration. Melbourne’s lanes and alleyways tell a unique story. As representations not only of our past, but also of our ever-evolving present, they deserve our protection.

Endnotes

[1] W Bate, Essential but unplanned: the story of Melbourne’s lanes, State Library of Victoria in conjunction with City of Melbourne, Melbourne, 1994, p. 11. There is some discrepancy over the spelling of ‘Latrobe’ or ‘La Trobe’. I have used ‘Latrobe’ in this article as it is the spelling most often used in the primary sources that I consulted. However, ‘La Trobe’ is most commonly used today.

[2] PROV, VA 511 Melbourne, VPRS 5708/P2, Rate Books: 1845-1900, Ward of Gipps.

[3] Sands & Kenny’s commercial and general Melbourne directory first appeared in 1857 and was published annually. In 1862 it continued as Sands & McDougall’s commercial and general Melbourne directory, and was published annually, with various name changes, until well into the twentieth century.

[4] PROV, VPRS 5708/P2, Ward of Gipps.

[5] R Annear, A city lost and found: Whelan the Wrecker’s Melbourne, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2005, p. 3.

[6] Bate, Essential but unplanned, p. 12.

[7] M Loh, ‘Chinese’, in eMelbourne – The encyclopedia of Melbourne online (accessed 5 September 2011).

[8] PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Unit 442, File 114/486, will and probate records of Henry Triplett.

[9] Bate, Essential but unplanned, pp. 24, 93.

[10] FW Hume, The mystery of a hansom cab, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1971, p. 100.

[11] Little Latrobe Street did not, in fact, escape scandal completely. The Devon and Cornwall Hotel, at number 50, gained some notoriety in 1886 when it was the scene of a brutal murder, witnessed by George William Buttrey, the proprietor of the hotel. This was reported in both local and inter-colonial newspapers at the time, for example: ‘Death by violence’, The Argus, 25 February 1886, p. 4h; ‘Murder of a woman in Victoria’, Maitland mercury & Hunter River general advertiser, 27 February 1886, p. 7a.

[12] W Booth, Social service in the Salvation Army, Salvation Army, London, 1903, p. 32.

[13] PROV, VA 511 Melbourne City, VPRS 11202/P1 Building Application Index [1916-1993].

[14] ibid.

[15] Australia ICOMOS [International Council on Monuments and Sites], The Burra Charter: the Australia ICOMOS charter for places of cultural significance 1999: with associated guidelines and code on the ethics of co-existence, Australia ICOMOS, Burwood, 2000.

[16] See City of Melbourne website, ‘Laneway Commissions’ (accessed 5 September 2011).

[17] F Harrisson, ‘Melbourne laneways: a landscape architect reflects on her involvement with the redevelopment of two iconic Melbourne laneways’, Landscape architecture Australia, no. 117, February 2008, pp. 41-2.

[18] See Melbourne Heritage Action Group website (accessed 5 September 2011).

[19] See J Dowling, ‘Lane land sales ring alarm bells for revenue watchers’, The Age, 21 October 2010 (accessed 5 September 2011).

[20] Bate, Essential but unplanned, p. 16.

[21] Victorian Heritage Database: H7822-2137; H7822-2138; H7822-2139; H7822-2140; H7822-2141; H7822-2142; H7822-2143; H7822-2144; H7822-2145; H7822-2131; H7822-2132; H7822-2133; H7822-2134; H7822-2135; H7822-2136. The searchable online database is on the Victorian Government’s Department of Planning and Community Development website (accessed 5 September 2011).

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples