Last updated:

‘The Mystery of the Cottage in Burnley Park’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 12, 2013. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lee Andrews.

This is a peer reviewed article.

The circumstances surrounding the construction of the nineteenth-century cottage in Burnley Park, in the inner Melbourne suburb of Richmond, have long remained a puzzle. In 2005 the cottage was threatened with demolition, and this became the catalyst for the research which is documented in the present article. Using comprehensive records held by PROV, the cottage was found to be highly significant – both architecturally and historically. Built originally for a Crown lands ranger, the cottage survives today as the third oldest park keeper’s residence in Victoria. One of the Public Works Department’s ‘tiny architectural gems’, complete with early remnant elm-lined road alignment, its association with the Survey Department and Robert Hoddle links it to the very beginning of white settlement in Victoria.

It is now clear that a full heritage assessment of the cottage within its parkland setting is imperative. Only then will its cultural significance, not only to Richmond, but to the state of Victoria, be clearly established, and its future appropriately protected.

The Search Begins

This article documents the search to establish the date of construction of a nineteenth-century cottage in Burnley Park, in the inner Melbourne suburb of Richmond. Establishing a definitive date for, and the circumstances leading to, the erection of the cottage became critically important in 2005 when implementation of a master plan for Burnley Park required demolition of the vacant cottage to create additional open space. An independent heritage report approved the cottage’s demolition, yet nothing was known about the building’s early history. In response to this threat, the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) classified the cottage and the greater parkland in which it sits, once known as Richmond Park, as being of state significance.[1] Despite comprehensive research into the history and development of the park and cottage undertaken for the classification report, almost nothing was found about the history of the cottage prior to the 1870s, or the circumstances or date of its construction.[2] However, as part of the classification process, physical examination of the masonry section of the cottage by leading heritage architect Nigel Lewis[3] suggested a floor plan of exceptional interest, warranting further investigation.

A new search was necessary. Tender and contract records held by PROV were initially consulted. Far from providing straightforward details regarding the cottage’s construction, the records were highly puzzling. The site’s change of use, statutory control and name made the search for information complex and at times baffling. An intriguing, frustrating, and ultimately highly illuminating journey through the public records ensued.

Tracing the Story Back to Melbourne’s Beginnings

It became clear that, in order to unravel what promised to be a highly complex story surrounding the cottage, it would be necessary to return to the early European history of the parkland in which the cottage was constructed.

Burnley Park, in which the cottage stands today, is part of a much larger tract of land which, from 1862, was gazetted as ‘Richmond Park’ – Richmond’s first public park.[4] Prior to 1862, the area was known as the Survey Paddock. Following the establishment in 1836 of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales (later Victoria), the Governor, Sir Richard Bourke, had directed that a branch of the Surveyor General’s Department be set up in Melbourne to survey the new district. The first survey officers, led by Robert Russell, were appointed on 10 September 1836.[5] Shortly afterwards, however, in early 1837, Russell was replaced by Robert Hoddle as senior surveyor for the district. Hoddle, appointed Officer-in-Charge of the Port Phillip Survey Department, arrived in Melbourne with Bourke in March 1837,[6] and began the task of laying out the township of Melbourne and surrounds. At this time two large government reserves were set aside for the needs of the police and the Survey Department – the ‘Government Paddock’ and the ‘Survey Paddock’.[7] The Survey Paddock was reserved for resting the horses and bullocks used in survey expeditions.

Comprising 193 acres (78 hectares) of land east of Melbourne, in what later became the municipality of Richmond, the Survey Paddock was ideally suited to the Survey Department’s needs. Surrounded on all but one side by a large bend of the Yarra River, the lower ground consisted of wide alluvial floodplain, dotted with lagoons and waterholes and supporting a woodland of river red gums, while the steep river banks led to rocky outcropping on higher ground, well above the flood line.

A similar reserve of some 220 acres (89 hectares) was also set aside for government purposes on the eastern edge of the Melbourne township in what is now East Melbourne. This reserve, which stretched to Hoddle Street in the east and fronted the Yarra River on the south, was divided into two sections – the ‘Government Paddock’ (sometimes referred to as Government Paddock No. 2), and adjoining and to its immediate west, a smaller ‘Police Magistrate’s Paddock’ (also known as Government Paddock No. 1). A temporary cottage for Police Magistrate William Lonsdale was erected here in 1837 (followed by a more permanent pre-fabricated structure), as well as police barracks, a Native Police camp, and a temporary gaol.[8]

The Government Paddock (later known as Richmond Police Paddock), together with the adjacent Police Magistrate’s Paddock (later part of Flinders Park) and the Survey Paddock (later Richmond Park) to its east, constituted the earliest reservations of public ‘parkland’ in Melbourne.[9] The nomenclature used for these reserves caused considerable confusion during searches for the origins of the cottage.

The Old Hut and the Survey Paddock

As head of the Port Phillip Survey Department, Hoddle was in charge of all matters concerning the Survey Paddock. From at least 1844, official correspondence indicates that Hoddle had appointed William McMurray, described as a ‘free immigrant on no pay but rations’ to be in charge of the Survey Paddock.[10] As well as the Survey Department’s horses and oxen, horses belonging to the District Police were also permitted to graze in the Survey Paddock. It appears that Hoddle allowed a district constable to be stationed here temporarily to accept and oversee the police horses, at least during a period in late 1844 when Hoddle was ‘absent’. In correspondence between Hoddle and one of his draftsmen, William Buckley, in November 1844 Hoddle instructed:

Sir, if it is necessary, the District Constable [later identified as a Constable Tucker] should reside in the neighbourhood of the Survey Paddock, he can occupy the old hut – McMurray remaining where he is.[11]

Hoddle’s reference to the ‘old hut’ is the earliest mention of a dwelling in the Survey Paddock that has been found to date. Although the correspondence gives no further details, it is likely that the hut was fashioned from rough-hewn timber slabs cut from trees growing on the site, predominantly river red gum. It appears that the ‘old hut’ may have been pressed into service some years later to provide accommodation for the constabulary once again – this time on a more permanent basis. On that occasion it would be Hoddle himself requesting a police presence.

The Puzzle of the Two Murphys

With the discovery of gold in 1851 in the newly separated Colony of Victoria, Melbourne experienced marked social upheaval. The problems created by a mass exodus of men to the goldfields were exacerbated by a huge influx of gold seekers into the town en route to the diggings. This was further compounded by the episodic return of large numbers of unruly ‘diggers’ to Melbourne for Christmas and other festivities. With police numbers decimated by the lure of gold, keeping order was extremely difficult. In response, the government expanded its program of appointing ‘special constables’ to augment the duties of the now greatly diminished police force. Undoubtedly to protect valuable survey horses and bullocks, a ‘Constable Murphy’ had been placed in charge of the Survey Paddock by January 1852,[12] and Hoddle soon found the need for a permanent ‘police’ presence there. On 17 July 1851, a mere sixteen days after Separation, Hoddle was appointed the first Surveyor General of Victoria.[13] In this capacity he wrote to the Crown Surveyor, SA Perry, in Sydney on 2 June 1852:

Sir, In reference to your letter of the 3rd instant (B52/68) relative to granting the Constable in charge of the Survey Paddock. I have to request the favour of His Excellency to appoint Mr Murphy, late Sergeant of Police, as Special Constable to Survey Paddock, it being absolutely necessary in these unsettled times to have a trustworthy man always there.[14]

Hoddle also informed Perry that the Special Constable in question, one James Murphy, had returned from the gold diggings and already taken charge of the Survey Paddock.[15] It has previously been assumed that James Murphy was the ‘Constable’ in charge of the Survey Paddock mentioned in official correspondence from January 1852, however the records suggest a second possibility. Another Sergeant of Police, one Walter Murphy, was listed as being in the Survey Paddock in March 1852.[16] Unlike James Murphy, Walter had not abandoned his employment to try his luck on the goldfields, as so many of his fellow policemen had.[17] It appears that Walter Murphy, who had been employed ‘in various Government departments’ since 1843,[18] may have been replaced by James Murphy around June 1852, after the latter had returned from the goldfields and had then been unemployed. Documentary evidence points to the possible reason for this being that the two were brothers, Walter being granted probate of James’s estate in 1859.[19]

In February and March of 1853 Walter’s address was no longer the ‘Survey Paddock’ but merely ‘Richmond’,[20] further supporting the idea of a ‘handover’ at the Survey Paddock, which was facilitated by the fact that both men were police sergeants and thus both perfectly qualified for the position. While James Murphy soon faded from the documentary record, Walter Murphy continued to be closely associated with the Survey Paddock for many years.

An Attempt is Made to Procure a New Dwelling

As Hoddle believed that it was ‘absolutely necessary that a trustworthy man should always be there [in the Survey Paddock]’,[21] Special Constable James Murphy would have undoubtedly been required to reside on site. In Victoria, a variety of accommodation was provided for ‘police purposes’, including a ‘Hut’ or ‘Tent’ at a cost of £40, and an ‘Iron House’ or (other) ‘House’ at a cost of £53.[22] The Survey Paddock’s James Murphy however seems to have been a special case. Later correspondence within the Department of Crown Lands and Survey suggests that there was no provision allowed for accommodation for this ‘Special Constable’.[23] It is therefore likely that Special Constable James Murphy was forced to reside in the ‘old hut’ mentioned in 1844, as there was a general shortage of accommodation throughout the colony during the 1850s.

By December 1854 James Murphy appears to have departed, and Walter Murphy was again residing in the Survey Paddock, with his address given in one instance as ‘Walter Murphy’s, Survey Paddock, Richmond’.[24] In mid-1855 the Surveyor General’s Department requested the construction of a ‘new hut’ in the Survey Paddock (at an estimated cost of £90.0.0). This request was rejected by Governor La Trobe, who advised he was ‘unable to sanction this expenditure under the present circumstances’.[25] No further explanation was given. It seems likely that the request for a new hut was initiated by the District Surveyor Clement Hodgkinson, who was then stationed in the Survey Paddock. Hodgkinson would come to have a close and enduring association with the Survey Paddock over many years.

Clement Hodgkinson and the Survey Paddock

The gold rush period saw an astounding increase in the population of the colony. In the twelve months immediately following the official discovery of gold in 1851 the population of Victoria doubled from 77,345 to over 160,000,[26] and between 1851 and 1854 Melbourne’s population increased fourfold.[27] In April 1853, to facilitate the increased land sales throughout the colony that were expected from such growth, Hoddle recommended the division of the colony into separate survey districts, each with its own survey office and district surveyor, and over the next few years this plan was implemented.[28] Richmond was located within the survey district of Bourke,[29] and the survey office for Bourke was erected in the Survey Paddock.[30] By 1854 Clement Hodgkinson was appointed District Surveyor for the County of Evelyn and half of Bourke, and evidence suggests that both his (survey) office and his family residence were located in the Survey Paddock between at least 1854 and late 1857.[31] Indeed, on a ‘pond’ adjacent to his cottage in the Survey Paddock, Hodgkinson conducted evaporation experiments in relation to the reservoir at Yan Yean.[32] Tragically, Hodgkinson’s wife Amelia, aged only twenty-seven, died in the Survey Paddock residence in 1855 following the birth of their sixth child.[33]

During this period Richmond underwent a formative change. Although land sales had commenced in Richmond in 1839 it was not until the mid to late 1850s that intense subdivision of its previously expansive and largely rural blocks took place. Reflecting this growth, Richmond was gazetted as a municipal district on 24 April 1855.[34] The following year, Clement Hodgkinson was appointed to the honorary position of consulting engineer and in this capacity he was instrumental in laying out Richmond’s main streets.[35]

A New Hut and a Third Murphy

Working and living in the Survey Paddock, Hodgkinson would have been very aware of the need for a new hut for Walter Murphy in 1855. By this time, Walter had returned to take charge of the Survey Paddock, the title ‘special constable’ having been replaced by ‘Crown land ranger’ or ‘paddock keeper’. It appears that, in the absence of departmental assistance, Walter Murphy took matters into his own hands and built a new hut himself. This is strongly suggested by Hodgkinson’s written departmental reference to the hut years later, in 1860. In March 1860, Walter Murphy was dismissed after a complaint of ‘neglect of duty’ by ‘Head Ranger Bickford’.[36] Murphy’s pleas to be re-instated were ignored, and as a result, in June 1860 he claimed re-imbursement for ‘the cost of erecting a hut in the Survey Paddock’.[37] Regarding this claim, Hodgkinson recommended that because of the

peculiar circumstances under which the hut was erected [author’s emphasis] the Honorable the Commissioner of Lands and Survey has suggested that Murphy the late caretaker of the Survey Paddock should be repaid whatever sum he can show to have actually spent in erection of the hut in question.[38]

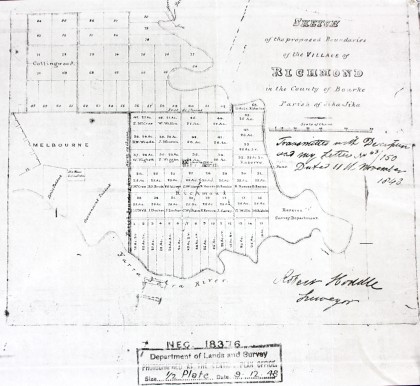

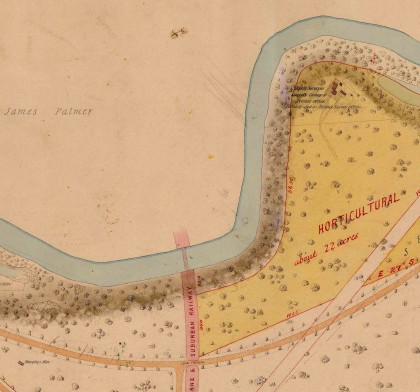

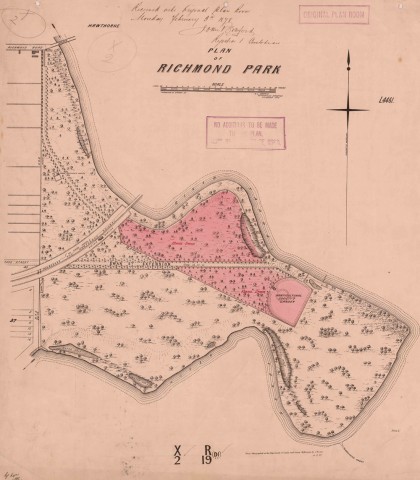

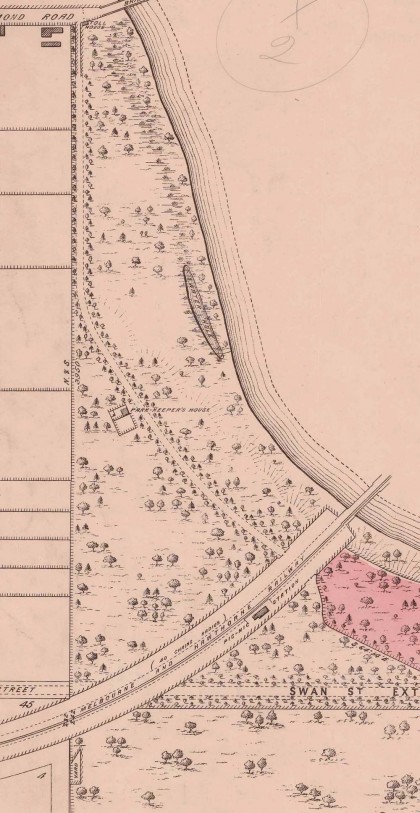

Although Murphy claimed £51.3.0 was expended on its construction, the hut was officially valued at only £34 and it appears that, despite Hodgkinson’s advocacy on Murphy’s behalf, the smaller amount was paid. The location of this dwelling, shown on an 1862 plan of the Survey Paddock as ‘Murphy’s Hut’ (see Images 1 and 2), matches that of the caretaker’s cottage extant today.

Walter Murphy was quickly replaced by another Crown land ranger – a Michael Murphy.[39] While evidence suggests Walter and James were brothers, no evidence has been found that they were in any way related to Michael. It also appears that Michael Murphy was transferred from his position as ‘ranger at St Kilda Road’ to replace Walter Murphy.[40]

In early July 1860, shortly after replacing ranger Walter Murphy in the Survey Paddock, ranger Michael Murphy requested that his accommodation there – the hut Walter had built – be repaired. The request, the first of many on this topic, was referred to Clement Hodgkinson, by this time Deputy Surveyor General.[41] Murphy repeated the request in early August, noting that the hut was in a dilapidated state and needed repair.[42] The poor state of the hut and the unwillingness or inability of the government to remedy the situation may have prompted Michael Murphy, a mere few months after his transfer to the Survey Paddock, to apply to return to his position as ranger, St Kilda Road.[43] This request, too, seems to have been rejected.

Over the next twenty months Michael Murphy continued to press for the necessary repairs to the hut. In June 1861, for example, he renewed his request, writing again to Clement Hodgkinson, who had recently been promoted to the position of Assistant Commissioner and Secretary of a newly formed entity – the Board of Crown Lands and Survey.[44] In response to Murphy’s request, Hodgkinson noted:

no action appears to have been taken in regard to request for repair of this hut on 19 June and it is now uninhabitable. Could a small iron building be furnished for the paddock keeper or any kind of hut containing 2 small rooms. If this could be supplied I will send in a request accompanying 3/8.[45]

However, the ensuing correspondence advised that the old hut was found to be not worth repairing, and as there was no provision in the Appropriation Act for quarters for a paddock keeper, Hodgkinson was prevented from recommending any expenditure on account of this.[46]

A New ‘Lodge’ for a New Park

After yet another round of requests from Michael Murphy in February and April 1862 for repairs to the hut,[47] Hodgkinson again attempted to resolve the issue. This time, in his new position, he was able to directly influence the outcome in Murphy’s favour. The separation of technical and administrative responsibilities, as occurred with the creation of the role of Assistant Commissioner, transferred real power from the Surveyor General to Hodgkinson.[48] In the case of the Survey Paddock hut, the matter came, in due course, to the attention of the Inspector General (and Chief Architect) of Public Works, William Wardell.[49] Wardell asked Hodgkinson if Murphy was entitled to quarters. Contrary to the advice Hodgkinson had received less than a year before, the record shows that on this occasion Hodgkinson informed Wardell that Murphy was entitled to accommodation. In response, Wardell wrote: ‘I will recommend [?] the repairs for the sanction of the Board of Land and Works. 8/5/1862’.[50] Thus, the documentary record appears to suggest that, unless the rules surrounding quarters for paddock keepers had changed, Clement Hodgkinson, in his new position, stretched the rules to enable Michael Murphy’s accommodation in the Survey Paddock to be finally addressed. No doubt the hut was deemed ‘not worth repairing’, as was the conclusion a year before, and so a new building needed to be constructed.

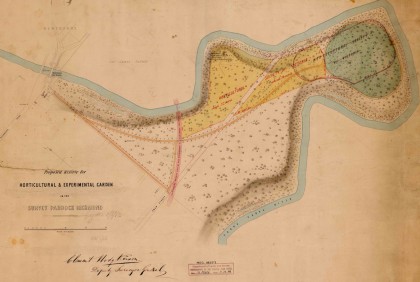

Hodgkinson may have felt the need to manipulate the situation to ensure the continued protection of the reserve by an on-site policing presence. Between 1858 and 1862 proposed changes in use, various incursions and a thwarted land sale all posed threats to the Survey Paddock’s largely virgin river red gum woodland. The destruction of the colony’s indigenous trees had become a major environmental concern, and even Melbourne’s parks and gardens were being stripped for firewood.[51] In late 1858 Richmond Council had successfully lobbied to have the Survey Paddock reserved as Richmond’s first public park.[52] By 1862 a number of changes to the reserve were occurring. The impending transfer of the Survey Paddock’s control to Richmond Council, the planned extension of Swan Street eastwards through the reserve, and the development of a large area of the reserve as experimental gardens by the Horticultural Society of Victoria may have created a sense of urgency in Hodgkinson. By ensuring the continuation of the ranger’s twenty-four hour presence Hodgkinson perhaps felt he could best protect the natural scenic qualities and indigenous vegetation of the still rural site.[53]

Whatever the reason, and as a direct result of Hodgkinson’s advocacy, tenders were soon called for construction of a ‘lodge’ for ranger Michael Murphy. Finding incontrovertible facts regarding the lodge’s construction, however, has proved surprisingly difficult, and has led to a laborious process of cross-checking and elimination to uncover a clear picture of events.

What’s in a Name?

The location of the new lodge was the first problem encountered. No lodge is listed in any departmental records as being built in the Survey Paddock, or even ‘Richmond Park’ (the new name given to the Survey Paddock by Richmond Council in May 1862). Both the Index to the Victoria Government gazette (1862) and the Gazette itself record items under the names ‘Richmond Park’, ‘Survey Paddock’,and ‘Richmond Reserve’. All three names refer (in this instance) to the same site.[54] To add to the confusion, the Public Works Department, as the responsible body, lists a contract for a ‘Lodge at Richmond Police Reserve £190.0.0′ with a completion date of 17 September 1862.[55]

Documents and plans from around this period indicate a large number of ‘reserves’, ‘paddocks’ and ‘parks’ to the east of the centre of Melbourne. Some of the names were confusingly similar. For example, the names ‘Richmond Park’, ‘Richmond Reserve’, ‘Richmond Police Reserve’, ‘Richmond Depot’, ‘Government Paddock’, ‘Survey Paddock’, ‘Government Survey Paddock’, ‘Richmond Stockade’ and ‘Police Paddock Richmond’ all appear in various documentary sources of the time. Some of these names were used interchangeably and often incorrectly, not only by the public, but also in departmental correspondence. As early as 1858, for example, a ‘footpath, Richmond Park’ is listed in the Index to the Public Works Department Outwards Correspondence, however the name ‘Richmond Park’ would not officially exist for another four years. The identity of this location was almost certainly what was also then referred to officially (and unofficially) as the ‘Richmond Paddock’ or ‘Government Paddock’. The confusion was exacerbated by the fact that the reserve to which these names referred was not actually in Richmond, but was in the location of what is now Yarra Park, in East Melbourne.[56] The confusion and inter-changeability of names continued well into the 1870s. For example, two letters published in the Argus in 1879 both discuss features in the ‘Richmond park’, but the context of the letters makes it clear that it is Yarra Park, or the old Government (or Police) Paddock, that is being referred to.[57]

The documentary record presents yet another layer of confusion, this time regarding the extent and nature of the building works. While the Victoria Government gazette described the works simply as ‘Lodge at Richmond Reserve’, the Yearly Abstract of Costs and Register of Works and Buildings – Metropolitan District and Suburbs[58] recorded works which had been undertaken in the ‘Survey Paddock’ and ‘Richmond Park and Recreation Grounds Richmond’, both of which were the same reserve. Under the former name, page 365 indicates that in 1862 there were ‘repairs to cottage’ of £2.17.6, and a verandah was also erected at a cost of £45. However, under the latter, an entry for 1862 shows ‘Extra works at Lodge: £190.0.0’. This was the full amount accepted for building the entire lodge, as recorded in the Public Works Department contract (see above). Entries under both names have the same folio number for part, but not all, of the works listed, adding further to the confusion.

The Victoria Government gazette in 1862 recorded that Contract 1106 had been awarded to J Radcliffe for construction of the ‘Lodge at Richmond Reserve’ for £190.[59] The Register of Contracts accepted and gazetted for 1862 confirmed that Contract 1106, from the vote 59/18/10, was paid in four instalments – with the final payment on 21 October 1862.[60] To confirm that these entries were indisputable proof of construction of a new dwelling for ranger Michael Murphy in the Survey Paddock, further corroboration was needed.

Ranger Murphy and ‘his house’

Confirmation came, fittingly, from none other than the pen of Ranger Michael Murphy himself. On 3 September 1862, Murphy wrote to the Department of Lands and Survey advising that ‘there will be certain additions required to the house now being erected in the Survey Paddock’.[61] The Index to this correspondence confirms that it was ‘his house’.[62] As if to finally seal the evidence, Public Works Department Ledger 12 (1862) states that the first instalment had been claimed by Radcliffe on 3 September, and on 14 October Radcliffe claimed for constructing Murphy’s ‘certain additions’ – a ‘verandah and water closet to cottage at Survey Paddock’ at a cost of £45 – an amount additional to the original contract price of £190. Two months later, G Dalton fitted ‘chimney pots to cottage in Survey Paddock’ at a further cost of £2.17.6.[63] These entries correspond exactly with the entries for both the Survey Paddock, and Richmond Park and Recreation Grounds, Richmond, in the ‘Yearly Abstract of Costs and Register of Works and Buildings – Metropolitan District and Suburbs’, as detailed above.

Ledger 12 also reveals that although Radcliffe undertook considerable construction for the Public Works Department around this time, he was not employed on any other projects in Richmond at the time, nor was he working on any lodge constructions in Richmond Police Reserve or Richmond Paddock.[64] Thus it could finally be confirmed that a new lodge for ranger Michael Murphy was constructed in the Survey Paddock (Richmond Park) by J Radcliffe for the Public Works Department between 3 September and 21 October 1862, with chimney pots being added in December of that year.

A Drawing is Found

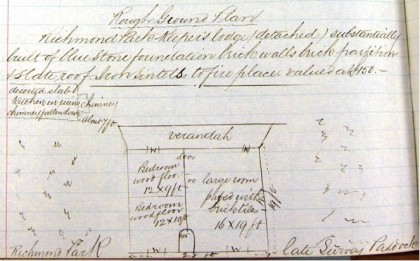

The only known surviving plan of the lodge is an annotated sketch of its floorplan prepared in 1867 by Richmond Council for insurance purposes.[65] At that time Richmond Council valued the ‘substantially’ built ‘Richmond Park Keeper’s Lodge’ at £150. The sketch confirms that the masonry section of today’s cottage was indeed the ranger’s lodge, the floorplan having changed little over one hundred and fifty years.

The 1867 sketch of the lodge reveals a three-roomed layout with central curved entry foyer. The floor of the largest room was paved with brick tiles, while the other two floors were timber. A verandah, as requested by Michael Murphy as ‘additions’, was added to the rear of the building, possibly to afford sheltered access to the ‘deserted slab kitchen in ruin’ with its ‘chimney fallen down’ described on the sketch, which may have been retained for use as a kitchen between 1862 and 1867. This deserted slab kitchen was undoubtedly ‘Murphy’s Hut’, built c.1855.

A ‘tiny architectural gem’

Between 1859 and 1868 William Wardell was responsible for the construction of all civil public buildings in Victoria, with all drawings and plans prepared under his supervision.[66] Building specifications were exacting and tightly controlled. For example, specifications for ‘some additions’ to police buildings in Warrnambool (16 November 1861) and ‘Portland gaol’ are extremely detailed, and the specifications for the gardener’s cottage at Sunbury Industrial School in 1866 provide an astounding level of detail, down to the number of screws required.[67]

Under Wardell the quality of buildings, regardless of size, produced by the department between 1859 and 1877 was remarkably high.[68] The ranger’s lodge at Richmond Park was no exception. Nigel Lewis’s architectural inspection in 2005 revealed all timber sections, chimney bricks and carpentry in the roof space to be of the highest standard. The internal solid door frames with chamfered surrounds, mitred at the corners, are of unusually large section oregon (Douglas fir).[69] Surviving wide hardwood battens and broken slate roofing tiles found within the roof space confirm the building’s original slate roof. With bluestone foundations, outer walls of triple brick and double brick internal walls, the ranger’s lodge was built to last.

The lodge’s simple floor plan marries a layout typical of ‘keepers’ quarters’ and ‘watchhouses’ from the early 1850s with unusual touches of architectural refinement, for which Wardell is likely responsible. For example, keepers’ quarters, designed by Victoria’s first Colonial Architect Henry Ginn in the early 1850s, feature small or no eaves, hipped roofs, small central front porches, angled fireplaces and no central halls. The three-roomed watchhouses in Brighton, Pentridge and Richmond, designed by Ginn, also feature a central entry foyer which affords entry to all rooms, thereby negating the need for an access hall.[70]

While a central entry foyer was typical in small public buildings, the incorporation of a curved room form was highly unusual, and reminiscent of much earlier public building styles from the 1820s found in Tasmania and New South Wales, and later in Victoria.[71] The 1867 sketch confirms that the curved wall is indeed original, as the 2005 roof space inspection indicated, and not a 1930s addition as had been previously suggested. Wardell may have added the curved entry foyer and centrally placed chimney (unusual for a double-fronted house) to suggest an element of Classicism and simple formality. In addition, the medieval or Gothic character of the solid door frames, constructed of unusually large section timber sitting within the double brick reveal, is consistent with the design predilection of Wardell, an eminent Gothic Revivalist. These architectural devices provide a hint of a picturesque exterior, as could be expected for a residence set within a large parkland. In the quality of its construction and the restrained elegance of its design, Michael Murphy’s lodge was one of the Public Works Department’s ‘tiny architectural gems’.[72] Lodges and other small ornamental structures such as this were often incorporated in the layouts of public and private parkland as part of the fashion for the picturesque, popular in Britain in the late eighteenth and early to mid nineteenth century. It is likely that the pattern-book designs of the Scottish landscape gardener JC Loudon were an influence here.[73] The lodge’s design was possibly a modest form of the kind of refined and ornamental structure recommended by Loudon, and upheld by Wardell, as best suited to the picturesque landscape – in this case the tamed Australian bush of the Yarra flats.[74]

On 1 August 1862 the Survey Paddock, under its new name ‘Richmond Park’, was temporarily reserved from sale to become a public park. Although Richmond Council was responsible for its management, the rules and regulations governing the reserve were controlled by the Board of Land and Works,[75] and ranger Michael Murphy remained responsible for policing the reserve for the next four years.

Over the next few years Richmond Park underwent many changes but remained a rural retreat for residents not only of Richmond but also of wider Melbourne. Both Richmond Council and the Board of Land and Works were careful to protect its trees and scenic qualities. Richmond Park became a favourite site for picnics and relaxation, and was the scene of great festivities during New Year holidays, complete with bands, sports, games and amusements, boats on the river, and refreshment tents.[76] Access to the Park was afforded by the river or via the steam train which stopped at ‘Pic Nic Station’ (constructed in 1859) in the centre of the Park.

While Michael Murphy lived in the new lodge and protected the reserve’s unspoilt vegetation on behalf of the Board of Land and Works, Richmond Council employed the previous ranger and Richmond resident Walter Murphy to undertake various tasks in the park from around 1863. The council briefly appointed Walter ‘acting caretaker’ of Richmond Park from December 1865[77] until shortly after the apparent resignation of ranger Michael Murphy by December 1866.[78] Council even voted to ask Walter to occupy the vacated lodge, in his ‘official capacity as Park Ranger’, as soon as the keys were given to Council by the government.[79] With the handover of the vacant lodge to Richmond Council in early 1867,[80] Council’s first official ‘park keeper’ of Richmond Park was appointed. Sadly for Walter Murphy, the Council appears to have changed its mind. The position of park keeper was thrown open, and one Edward Plant was chosen from a field of forty-seven applicants.[81]

For almost one hundred years the lodge (and its later weatherboard additions) was home to the park keeper of Richmond Park. From 1907 to 1940 AT Carter, one of the longest practising park curators in metropolitan Melbourne, resided there.[82] By 1961 a new dwelling for the park keeper had been built to the north of the 1862 lodge. The original park keeper’s lodge (built adjacent to the site of Murphy’s Hut) together with associated stores, sheds and additions, became a council depot.

A Rare Example of a Once Common Feature

The mystery of the park keeper’s lodge was finally solved. With conventional building records such as tender notices and contracts inconclusive and puzzling, the search relied on a large suite of different kinds of government documents held by PROV. It was only through the painstaking corroboration made possible by these irreplaceable documents that the tangle of evidence could be unravelled and the story finally pieced back together. Far from being an unimportant building with little architectural merit and physical integrity, the records revealed that the 1862 masonry section of the lodge is indeed a tiny architectural gem, and a rare surviving example of a once common feature in public parks and gardens. Only two earlier known examples of caretakers’ residences remain in public parks and gardens in Victoria: the former under-gardener’s residence (1850) at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne, and the former curator’s cottage (earliest section 1858) at Portland Botanic Gardens.[83] The lodge is the oldest building used continuously for public purposes in the City of Yarra.[84]

The physical location of the 1862 park keeper’s lodge is evocative of the early history of the Survey Paddock, later Richmond Park, and the surveillance role of the park keeper. Erected beside the c.1855 hut which it replaced, the lodge still guards over the now lost ‘carriage drive’ which led through the grounds from the entry in Bridge Road. Adjacent to the lodge, a surviving length of the 1860s elm avenue which once flanked the carriage drive delineates the line of the drive, allowing the lodge, drive and avenue to be read as one cohesive element. The intact nature of this alignment and the combination of early architecture and remnant old elms are remarkably eloquent in illustrating the reserve’s long and fascinating history, which, through its association with Robert Hoddle and the Survey Department, reaches back to the very beginning of white settlement in Victoria. Clearly, this is an important site. Currently, protection of the site is limited to a City of Yarra heritage overlay, yet the research strongly suggests an importance beyond local council boundaries. In 2005 the National Trust classified Richmond Park as being of state significance. While the cottage was included in the classification, very little was known of its early history. Information since gleaned from PROV’s archives now makes possible, indeed demands, a full and rigorous assessment of the cottage and its curtilage to ensure an appropriate level of statutory protection. A comprehensive conservation analysis is now required to assess the cottage’s cultural significance, not only to Richmond, but to the state of Victoria. Further documentary and physical investigation is needed to clarify the sequential development of the building and remaining original fabric. Archaeological investigation of not only the building but also of lost elements within the parkland, including Murphy’s Hut, the carriage drive, Pic Nic Station, and the 1850s survey complex, has great potential to yield new information. Based on the findings of such a conservation analysis, recommendations regarding the future management of the building and its parkland context could be formulated to guide City of Yarra in its future protection of the site.[85]

Only then can we be sure that the cottage and its parkland setting are appropriately protected for future generations.

Endnotes

[1] National Trust of Australia (Victoria) Gardens Committee, ‘Classification Report – Richmond Park’, 2005.

[2] Sources consulted included the Crown Reserve file (Rs 152), held by Historic Places Branch, Department of Sustainability and Environment.

[3] N Lewis, ‘Gardener’s or caretaker’s cottage Richmond Park: report of site inspection made on 12 April 2005’, prepared for ‘National Trust of Australia (Victoria) Classification Report – Richmond Park’, 2005.

[4] Richmond Park, bounded by the Yarra River, Loyola Grove, Park Grove, Park Avenue, and a very small section of Bridge Road, no longer exists as a single parkland entity. Originally one unbroken area of woodland, Richmond Park today comprises a number of separate areas known by the following names: Burnley Park, Burnley Public Golf Club, University of Melbourne Burnley Campus (also known as Burnley Gardens), Botanica Corporate Park, Kevin Bartlett Sporting and Recreation Complex, and Melbourne Girls’ Secondary College.

[5] PROV, VA 943 Surveyor General’s Department, Port Phillip Branch (also known as the Melbourne Survey Office) – see About this Agency. Further detailed information about this period can also be found in Surveyor’s problems and achievements, 1836–1839, ed. M Cannon and I MacFarlane, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1988.

[6] G Scurfield, The Hoddle years, surveying in Victoria, 1836–1853, The Institution of Surveyors, Canberra, 1995, p. 140.

[7] Both these reserves are shown on Hoddle’s 1837 ‘Plan shewing [sic] the surveyed lands to the northward of Melbourne and allotments contiguous to it’ available on the State Library of Victoria’s website athttp://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/115307.

[8] H Doyle, ‘Dispensing justice: an historical survey of the theme of justice in Victoria’, a cultural sites network study, prepared for the Historic Places Section, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Melbourne, May 2000.

[9] H Doyle, Yarra Park Appeal, Heritage Council, expert witness report, February 2010.

[10] PROV, VA 4729 Commissioner of Crown Lands, County Of Bourke, VPRS 96/P1 Inwards Correspondence 1842–1853, Unit 1, Bag 3 – 1844, letter from William Buckley, Survey Office, 13 December 1844.

[11] ibid., letter from ‘Robert Hoddle, Surveyor’ to Mr Buckley (draftsman of the Survey Office), Survey Office, 4 November 1844.

[12] PROV, VA 943, VPRS 6765 Outwards Correspondence, Melbourne Survey Office, September 1849 – December 1854 (microfilm copy of VPRS 6), p. 68.

[13] Scurfield, The Hoddle years, p. 140.

[14] PROV, VA 943, VPRS 6/P0 Melbourne Survey Office, Letter Book, Unit 1, Item 52/179, 8 June 1852, p. 128.

[15] ibid., p. 135.

[16] Victoria Government gazette, no. 11, 17 March 1852, p. 257, list of unclaimed mail held at the Melbourne Post Office.

[17] Argus, 7 December 1864, p. 5.

[18] ibid.

[19] Argus, 8 April 1859, p. 6: under the heading ‘Law Report’, in the ‘matter of the goods of James Murphy, deceased’ the Supreme Court (of Victoria) granted ‘letters of administration’ ‘to Walter Murphy, brother and next of kin of the deceased [James Murphy], who died at Calcutta’.

[20] Victoria Government gazette, no. 9, 23 February 1853, p. 271; and no. 13, 9 March 1853, p. 346.

[21] PROV, VPRS 6/P0, Unit 1, Item 52/179, 8 June 1852, pp. 128 and 135.

[22] PROV, VA 856 Colonial Secretary’s Office, VPRS 12666/P1 Index to Inward and Outward Correspondence, Colonial Architect 1854–1855, Unit 1, under ‘P’, 2 October 1854.

[23] PROV, VA 669 Public Works Department, VPRS 969/P0 Minute Book,1861-1862, Unit 4, no date but appears to be 9 August 1861, p. 140.

[24] Argus, 20 December 1854, p. 7.

[25] PROV, VPRS 969/P0 Minute Book 1, 1855–1856, letter from the Colonial Secretary to the Colonial Engineer regarding building a new hut in the Survey Paddock, 6 June 1855.

[26] R Haldane, The people’s force: a history of the Victoria Police, Melbourne University Press, 1986, pp. 18 and 19.

[27] Victoria Police Management Services Bureau (comp.), Police in Victoria, 1836–1980, Victoria Police Force, Melbourne, 1980, p. 6.

[28] PROV, VPRS 6765, p. 229.

[29] The ‘survey district’ of Bourke appears to have conformed to the same boundaries as the ‘county’ of Bourke, which was established in 1843 (Victoria Government gazette, no. 74, 5 September 1843, p. 1147).

[30] Plans of the Survey Paddock in 1855 (Map of Melbourne and its suburbs, compiled by J Kearney, engraved by D Tulloch and JD Brown, Surveyor-General, Melbourne, 1885 – held at the State Library of Victoria and available online) and 1862 (see Image 3) show a small fenced complex of buildings described in the 1862 plan as ‘Deputy Surveyor General’s cottage & private office formerly used as District Survey Office’. Image 4 shows this clearly.

[31] Argus, 4 January 1854, p. 1; 5 March 1855, p. 1; 4 April 1855, pp. 6 and 7; 9 April 1855, p. 1; 17 April 1855, p. 4. Also PROV, VA 2878 Crown Lands Department, VPRS 6605/P0 Chief Commissioner Crown Lands, Inwards Correspondence, Unit 15, September 8 and 15 1857 – Hodgkinson complaining about the state of the road through the Survey Paddock: ‘I find it all together unsafe to drive at night along it …’.

[32] Argus, 4 April 1855, pp. 6 and 7: ‘Paper showing the Influence of Evaporation and the Quantity and Quality of the Water to be derived from the Reservoir at Yan Yean. Read before the Philosophical Society of Victoria, March 13th, by Clement Hodgkinson, C.E., district surveyor’. Also Argus,15 June 1855, p. 6, letter to the editor from Hodgkinson on the matter of evaporation.

[33] Argus, 17 April 1855, p. 4.

[34] Victoria Government gazette, no. 37, 24 April 1855, p. 1026.

[35] Victoria Government gazette, no. 103, 22 August 1856, p. 1392; PROV, VA 2494 Richmond Municipal District, VPRS 9986/P1 Council Minutes, Unit 1, 7 June 1856.

[36] This was Nicholas Bickford (1822–1901), who worked under Hodgkinson for many years and later was curator of parks and gardens for the City of Melbourne. He also laid out Fitzroy’s Edinburgh Gardens. See R Aitken and M Looker (eds), Oxford companion to Australian gardens, Oxford University Press in association with Australian Garden History Society, South Melbourne, 2002, p. 88.

[37] PROV, VA 538 Department of Crown Lands and Survey, VPRS 227/P1 Registers of Inward Correspondence (Lands) (microfilm – Drawer R), Unit 5, vol. B 234, 5 June 1860, letter from W Murphy claiming £51.3.0 for the cost of erecting a hut in the Survey Paddock Richmond. Letter referred to the Deputy Surveyor General. Progressive no. 60/3620.

[38] PROV, VPRS 969/P0, Unit 3, 11 July 1860, p. 331.

[39] PROV, VPRS 227/P1, Unit 4, vol. A, p. 94, letter no. 1411, 21 March 1860, application by E Bonfield for ‘keepership’ of Survey Paddock, vacant by the dismissal of Murphy who is reported by Ranger Bickford; vol. A, p. 95, 19 March 1860, letter from W Murphy in respect of charges brought against for neglect of duty; vol. A, p. 249, letter no. 3763, 4 July 1860, from Michael Murphy that the hut in the Survey Paddock needs repairing.

[40] ibid., Unit 4, vol. A, p. 162, 15 December 1860, letter from M Murphy requesting to be re-instated in his former situation as ranger at St Kilda Road as soon as the present ranger is removed.

[41] ibid., Unit 4, vol. A, p. 249, letter no. 3763, 4 July 1860: this appears to be the first request from Michael Murphy that the hut in the Survey Paddock be repaired. Referred to Deputy Surveyor General and Mr W Murrah (PROV, VPRS 969/P0, Unit 3, 11 July 1860, p. 331; ibid., p. 328).

[42] ibid., Unit 5, vol. B 317, letter no. 4523, 2 August 1860, from Michael Murphy regarding repairs needed to hut.

[43] ibid., Unit 4, letter from M Murphy on p. 162, dated 15 December 1860 requesting to be re-instated in his former situation.

[44] Victoria Government gazette, no. 63, 23 April 1861, p. 797.

[45] PROV, VPRS 969/P0, Unit 4, no date but appears to be 3 August 1861, p. 140.

[46] ibid, p. 140, no date but appears to be 9 August 1861.

[47] PROV, VA 538 Department of Crown Lands and Survey, VPRS 226 Index to Inward Registered Correspondence (microfilm – Drawer R), Unit 2, 1862, 1863, p. 260: under ‘Park keepers’ Murphy requests repairs to hut, February E 170 and E 359; VPRS 969/P0, Unit 4, p. 366, 24 April 1862, M Murphy writes to Crown Bailiff re condition of hut.

[48] G Whitehead, ‘Clement Hodgkinson: naturalist and landscape gardener’, talk presented to Collingwood Historical Society, 25 August 2009, p. 6; viewed at http://www.collingwoodhs.org.au/docs/clement-hodgkinson.pdf on 26 March 2013.

[49] Victoria Government gazette, no. 36, 25 March 1862, p. 529.

[50] As noted above, Murphy had written to the Crown Bailiff about the hut on 24 April 1862. His letter was referred to the Inspector General of Public Works. Meanwhile, Murphy also wrote to Hodgkinson requesting repairs (PROV, VPRS 969/P0, Unit 4, p. 375). Added was ‘see min. 228 – which was the question of Murphy needing to have a dwelling, to which Hodgkinson replied ‘Yes’ and signed it on 3 May 1862.

[51] Whitehead, ‘Clement Hodgkinson’, pp. 8 and 9.

[52] PROV, VPRS 9986/P1, Richmond Council minutes, 28 August 1857 and 8 October 1858.

[53] This is supported by comments made by Michael Murphy regarding the arrangements which led to the ranger remaining in Richmond Park after the handover. According to him, when the Park was gazetted the Council had consented to allow him to remain at the request of the Commissioner. Richmond Australian, 23 December 1865, under ‘Council Minutes’.

It is also likely that around this time plans were made to remove the residence and former district survey office occupied by Hodgkinson since the mid 1850s. Although the documentary record is strangely silent on this matter, the residence and office disappear from plans of the area after 1862 (for example, see Image 7). Changes to the reservation of land for the Horticultural Society’s Experimental Gardens nearby, resulting from catastrophic floods in 1863, may have been responsible for eventual removal of these buildings, located as they were on the higher ground subsequently sought by the Horticultural Society. Images 3 and 7 show the resulting new reservation of land. Eventually the reservation changed once again and only some of this land was used by the Horticultural Society.

[54] The Index to the Victoria Government gazette, 1862, p. 34 lists ‘Tenders for public works unconnected with railways and roads and bridges… – Various places: … Richmond, 1299 …’ and p. 1299 of Gazette no. 88, 25 July 1862 lists under ‘Public Works Office, Melbourne’ Tender 61, ‘Lodge at Richmond Reserve’. The Index, p. 29 lists both ‘Richmond. See Sites’ and ‘Richmond park, 1338’; and p. 32 lists ‘Richmond: Swan street extension through survey paddock, 1031’ and ‘Richmond park (formerly survey paddock), 1338’.

[55] PROV, VA 669 Public Works Department, VPRS 979/P0 Contract Books, vol. 5, 1862, p. 27.

[56] In PROV, VA 2494 Richmond Municipal District, VPRS 9983/P1 Outward Letter Books, Unit 2, p. 143, February 1860, references suggest that the names Government Paddock, Richmond Paddock and Richmond Police Paddock refer to the same place.

[57] Argus, 1 February 1879, 23 September 1879.

[58] PROV, VA669 Public Works Department, VPRS 957/P0, Yearly Abstract of Costs and Register of Works and Buildings – Metropolitan District and Suburbs, Unit 1.

[59] Victoria Government gazette, no. 97, 19 August 1862, p. 1483.

[60] PROV, VA 669 Public Works Department, VPRS 981/P0 Register of Contracts Accepted and Gazetted, Unit 3 (1862), p. 85.

[61] PROV, VPRS 227/P1, Unit 7, vol. F 475, letter 7313, 3 September 1862: Mr Murphy states there will be certain additions required to the house now being erected in the Survey Paddock. Referred to Inspector of Works.

[62] PROV, VPRS 226, Unit 2, p. 260, September: re: Murphy, additions will be required to his house (letter F 475).

[63] PROV, VA 669 Public Works Department, VPRS 69/P0 Ledgers, Ledger 12 (1862), pp. 250 and 251.

[64] ibid, p. 230.

[65] PROV, VA 2494 Richmond Borough, VPRS 9983/P1 Outward Letter Books, Unit 3, Parkkeeper’s [sic] cottage (rough ground plan), p. 465.

[66] B Trethowan, The Public Works Department of Victoria 1851–1900: an architectural history, Department of Architecture & Building, University of Melbourne, 1975, p. 51; DI McDonald, ‘Wardell, William Wilkinson (1823–1899)’, Australian dictionary of biography, vol. 6, 1851–1890, R–Z, Melbourne University Press, 1976. Available online, accessed 28 March 2013.

[67] PROV, VA 669 Public Works Department, VPRS 967/P0 Inwards Correspondence Files, Unit 54, first tied bundle.

[68] Trethowan, The Public Works Department, p. 51.

[69] Lewis, ‘Gardener’s or caretaker’s cottage’.

[70] PROV, VA 473 Superintendent, Port Phillip District, VPRS 4107/P1 Book of Plans by Clerk of Works, Henry Ginn (copy of original), Unit 1, no date, but some entries are dated 12 September 1853, pp. 28 and 29.

[71] Lewis, ‘Gardener’s or caretaker’s cottage’.

[72] Trethowan, Public Works Department of Victoria, p. 51.

[73] JC Loudon, Encyclopedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture and furniture, London, 1833.

[74] The natural beauty of the Survey Paddock / Richmond Park was captured by many artists from the 1860s, including Henry Burn (1869, 1870) and Louis Buvelot (1871). Henry Burn’s 1870 painting of Richmond Park can be viewed online at http://catalogue.statelibrary.tas.gov.au/item/?id=85121. Louis Buvelot’s 1871 painting entitled ‘Survey Paddock’ can be viewed online athttp://http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/col/work/4472.

[75] Victoria Government gazette, no. 90, 1 August 1862, p. 1338.

[76] Richmond Australian, 3 January 1863.

[77] Richmond Australian, 23 December 1865, under ‘Council Minutes – Correspondence’. Walter Murphy offered to take the role of ‘caretaker’ for the Council ‘at any salary they might appoint’. Council agreed to this offer and authorised the Mayor to make ‘an arrangement’ with Murphy. This was in response to the conflict Council had recently experienced with ranger Michael Murphy, employed by the colonial government.

[78] The details surrounding Michael Murphy’s departure have not been unearthed to date, but a Michael Murphy was appointed Crown Lands Bailiff in March 1868 (Victoria Government gazette, no. 27, 10 March 1868, p. 557).

[79] Richmond Australian, 22 December 1866, under ‘Correspondence’ in the ‘Council Minutes’.

[80] ibid., 5 January 1867, under ‘Correspondence’ in the ‘Council Minutes’.

[81] ibid., 20 April 1867, under ‘Local Intelligence – The Park Keepership’, p. 3(b).

[82] National Trust of Australia (Victoria) Gardens Committee, ‘Classification Report – Richmond Park’, 2005.

[83] Perhaps the best known example, the Gardener’s Cottage (‘Sinclair’s Cottage’) (1866) at Fitzroy Gardens, is in fact later than the earliest section of the Richmond Park cottage.

[84] G Butler, Heritage Advisor, City of Yarra, email to the author, September 2008.

[85] On completion of such an assessment, it is the author’s intention to write a follow-up article on the findings, to be published in Provenance.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples