Last updated:

‘The legal profession in colonial Victoria: information in records of admission held by Public Record Office Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 13, 2014. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Richard Harrison

The research described in the article has as its primary purpose the production of a complete and accurate list of lawyers admitted to practise in Victoria prior to 1901 from records held by Public Record Office Victoria (PROV). The secondary purpose is to gather any basic biographical data about those lawyers available in the admission records. The article describes the structure of the legal profession in the nineteenth century and provides an account of the changing names and structures of the superior courts with jurisdiction over Port Phillip and then Victoria. Discussion of PROV’s records of admission provides details of the relevant record series, their scale and format. Particular attention is given to the content of the records, and also to their completeness and some practical difficulties in using them. The article also looks briefly at some demographic characteristics of the barristers as a group: sex, age and ancestry

Background

The research presented in this article is part of a much larger project that aims to gather and structure basic biographical data on members of Australia’s professional, official, business and social elites in the colonial period.

The product of the research (and the larger project of which it is a part) will be structured data in multiple formats – databases, spreadsheets and e-books are planned at present – hosted on a dedicated website. The aim is to enable easy access to the data for anyone who wishes to use it, free of charge.

Institutional context

‘Admission to practise’ is the ceremony in which a layman becomes a lawyer. In colonial Australia, the Supreme Court in each colony was the body into which a person was admitted. For those who had not already been admitted to a court in the United Kingdom, it was the culmination of a years-long period of study and training. In the twenty-first century the Supreme Court in each state continues to be the body to admit lawyers to practise.

Prior to 1892, the Victorian legal profession, following the practice in England, was divided into two branches: (1) barristers and (2) ‘attorneys, solicitors, and proctors’ (informally called just ‘attorneys’).[1] Barristers (also called ‘counsel’; the ‘upper branch’ of the profession) tended to specialise in more complex legal work, had exclusive right of audience in the higher courts, accepted work only through attorneys and were not permitted to practise in partnership. Attorneys (later called ‘solicitors’; the ‘lower branch’) generally undertook more routine work, sometimes appeared in lower courts, worked directly with clients, and acted as intermediary between client and counsel where the latter had been engaged. They often practised in partnership. As will be detailed below, to gain admission barristers required more education than attorneys, including more extensive legal knowledge but also a broad, liberal education. To add to barristers’ professional precedence, they were officially treated as being the socially superior branch of the legal profession.[2]

From 1 January 1892 the two branches in Victoria were formally fused, so that all practitioners already admitted in one branch were permitted to practise in the other, and all future admissions were as ‘barristers and solicitors’.[3] However, the formal fusion did not carry over into the actual structure of the profession. The functional division that was in place before 1892 largely persisted afterwards, with lawyers describing themselves either as ‘barristers’ or ‘solicitors’ and practising in the areas traditional to those (former) branches.

Although a small number of lawyers practised in the District of Port Phillip in its earliest years of settlement, having been admitted in Sydney to practise in the Supreme Court of New South Wales, they lacked an institutional arrangement to set them apart from their brethren north of the Murray. The arrival in Melbourne in 1841 of Mr Justice Willis as Resident Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales marks the beginning of a distinctly local profession. On 12 April 1841 five barristers were admitted to practise in ‘The Supreme Court of New South Wales for the District of Port Phillip’ and on 8 May of that year fourteen men were admitted as attorneys.[4]

The court into which these practitioners and their successors were admitted changed its structure and designation several times. At Separation from New South Wales on 1 July 1851 it was re-designated ‘The Supreme Court of New South Wales for the District of Port Phillip now called as and being the Colony of Victoria’;[5] on 6 January 1852 it was succeeded by ‘The Supreme Court of the Colony of Victoria’;[6] and on 1 October 1915 that court was given its current name, ‘The Supreme Court of the State of Victoria’.[7] Despite all these changes of name and jurisdiction, the court’s admission records form continuous series from 1841 to 1891 and from 1892 into the twentieth century.

Key PROV records

As discussed above, there were three types of lawyer in practice in Victoria prior to 1901: attorneys (1841 to 1891); barristers (1841 to 1891) and barristers and solicitors (from 1892). Each type has its own series of records in PROV.

Attorneys (1841–91)

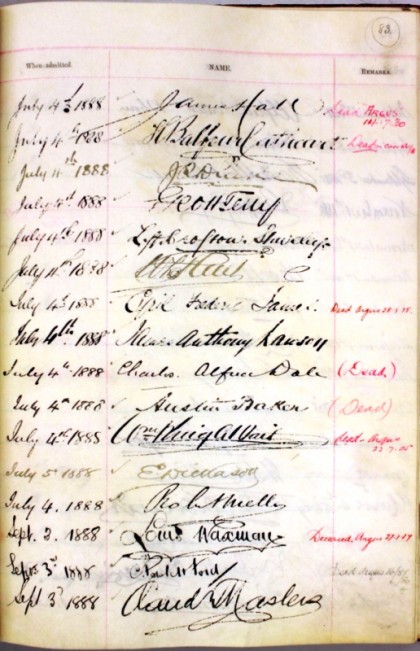

The basic listing of attorneys is PROV, VPRS 16237/P1 Roll of Attorneys, unit 1. This is a ledger of 93 pages, each normally with 16 entries, and hence with approximately 1,500 entries in total, commencing on 8 May 1841 and with its final entry dated 1 December 1891. Each page has three columns: ‘When admitted’ (day, month and year); ‘Name’; and ‘Remarks’ (noting any striking-off or readmission, and also in many cases the attorney’s death, the latter sometimes with the date). In about one-third of the entries the ‘Name’ is the attorney’s full name written in a clear, large hand. The other two-thirds have instead signatures of varying legibility in a range of inks, some of which have faded badly. While almost all signatures can be deciphered with some effort, around five per cent are illegible.

Some assistance in deciphering the signatures can be gained from PROV, VPRS 83/P0 Index to Admission Files of Attorneys to the Supreme Court, unit 1. This is a set of 38 file covers (paper glued onto a wooden backing) with attorneys’ names written in roughly chronological order within each letter of the alphabet.

Detailed records for each attorney are contained in PROV, VPRS 82/P0 Admission Files of Attorneys to Supreme Court, units 1 to 20. This series comprises 26 boxes each with around 40 bundles of documents, one for each attorney admitted.[8] The content of each bundle varies, depending on how much of the documentation has survived. Many bundles contain the full documentation for admission, which normally comprises:

- A certificate of the examiners that the candidate has fulfilled the requirements for admission.

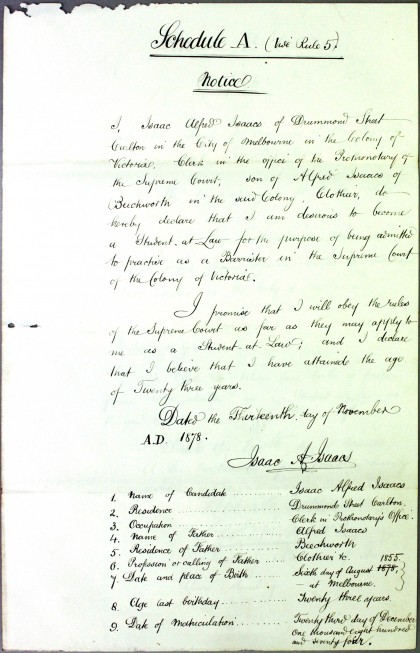

- A handwritten affidavit of the candidate for admission, which includes the candidate’s full name and address and a summary of (as relevant) migration to Victoria, pre-law career, education and articles of clerkship. From 1866 these affidavits (‘Schedule A’) also included a table of key data on the candidate including date of birth and birthplace; and father’s name, address and occupation.

- A handwritten certificate signed by two practising attorneys testifying to the candidate’s good character.

- Certificates of completion of required university studies.

- A large parchment document, the ‘articles of clerkship’ between the ‘clerk’ (the future attorney) and a practising attorney. Where the clerk was under 21 years old, as was often the case, the clerk’s father was also a party to the articles; thus the articles often provide valuable genealogical information.

- Attorneys already admitted to practise in the United Kingdom will have a handwritten certificate of such admission instead of the documentation of university studies and clerkship.

As noted above, most documents are handwritten. However, for the most part the writing is clear and easily read, and in any case most of the contents of the documents are similar for each candidate for admission, so that when one is familiar with the format the documents can be read quickly.

Much of the content of the candidate’s affidavit, with its details of the candidate’s education, training and legal experience, is also contained in documents in PROV, VPRS 105/P0 Reports of Examiners for Admission of Attorneys, unit 1. Usually, all the reports for a single term (there were four legal terms in a year) were collected into a multi-page document. This series is limited to attorneys admitted in Victoria between 1841 and 1871 who had already been admitted in the United Kingdom, but can be a useful alternative source to VPRS 82.

Two further sources are useful in cases where VPRS 82 files are deficient or missing: PROV, VPRS 5504/P0 Register of Articles of Clerkship, unit 1, a ledger for the period 1843 to 1906; and VPRS 16315/P1 Roll of Attorneys, County Court, Melbourne, unit 1, a ledger for 1847 to 1931; but note that only attorneys already admitted to the Supreme Court could be admitted to practise in the County Court.

Barristers (1841–91)

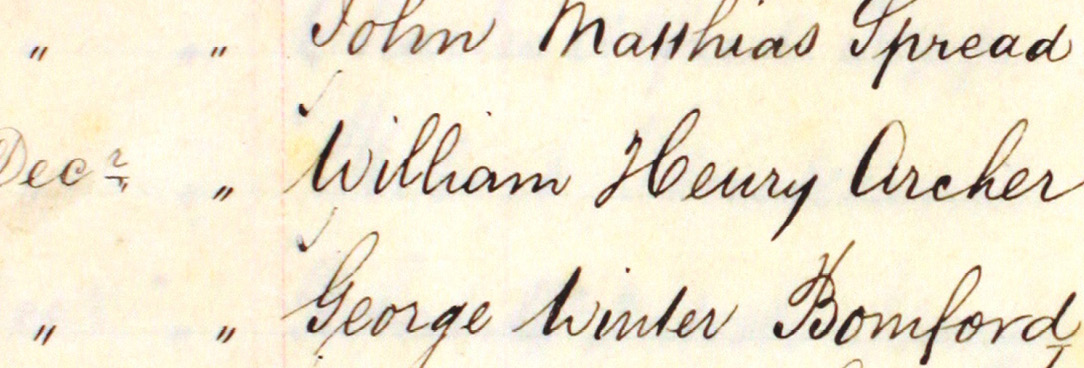

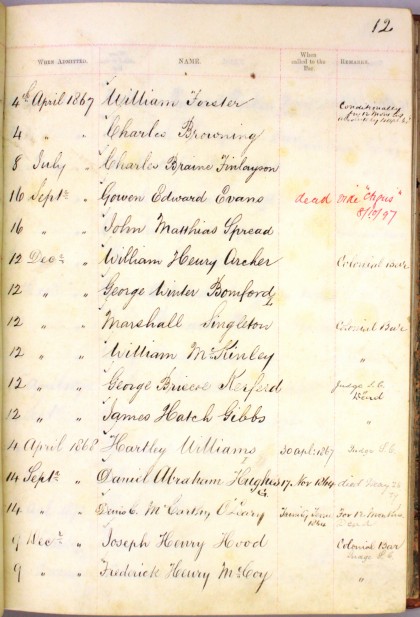

The basic listing of barristers is PROV, VPRS 16236/P1 Roll of Barristers, unit 1. As with VPRS 16237 this is also a ledger. The barristers’ roll differs in having an additional column for ‘When called to the bar’, which for barristers already admitted in the United Kingdom is the date of the original admission. The Inn of Court of such barristers is also indicated by a letter adjacent to the name.[9] All 424 entries in the Roll of Barristers are legible.

The ledger containing the Roll of Barristers also contains (effectively as a continuation of the barristers’ admissions) the admissions for barristers and solicitors from 1892 to 1933. There are 397 entries for admissions from 1892 to 1900, all of which are legible.

Detailed records for each barrister are contained in PROV, VPRS 1356/P0 Admission of Barristers Files, units 1 and 2. This series comprises two boxes, each with around 150 bundles of documents, or just over 300 in all (there is no documentation in this series for about 100 barristers). At best a bundle consists of documentation very similar to that described above for attorneys, less the articles of clerkship. Unfortunately, full documentation survives for only about 100 barristers, with most of the bundles comprising only a certificate of admittance.

Barristers and solicitors (from 1892)

As noted above, the basic listing of admissions of barristers and solicitors from 1892 to 1933 is in VPRS 16236. Detailed records of each practitioner admitted are in PROV, VPRS 468/P0 Barristers and Solicitors Admission Files, units 1 to 56. The content of these records is similar to that of VPRS 82, described above.

Legal education

Colonials and others

Lawyers who had been admitted to practise in the courts of the United Kingdom were entitled to admission in Victoria without further qualification.[10] The remarks here about legal education, therefore, are limited to lawyers who were first admitted in Victoria (barristers first admitted in Victoria are described as ‘colonial barristers’ in VPRS 16236).

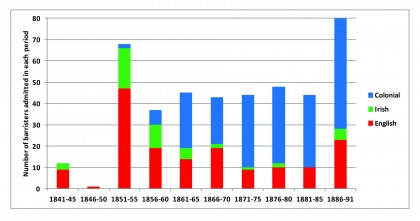

Prior to 1860, colonials were rare in the Victorian profession. However, their ranks swelled quickly in the early 1860s and they comprised a majority of admissions in each period thereafter.[11]

The education requirements for local admission were not limited to knowledge of the law. The ‘Rules and regulations for admission’ of 1853 required candidates for admission as barristers to pass a written examination of each of the following: Greek and Latin; mathematics and algebra; ancient history; English history; universal history; real property and conveyancing; common law, pleading and practice; equity and insolvency; criminal law; and evidence and the law of contracts.[12] Would-be attorneys had a less demanding range of examinations: real property and conveyancing; practice of the Court in its various branches; and criminal law.[13]

In 1865 the admission requirements were modified, so that certain university qualifications allowed a candidate for admission as a barrister to escape the examinations. The qualifications were a Bachelor of Arts degree, a Bachelor of Laws degree or passes of four examinations in law, all at the University of Melbourne ‘or in some University recognised by such University’.[14] At the same time the requirements for attorneys seem to have been raised. Now, candidates for admission as attorneys were required to pass the matriculation examination at the University of Melbourne, with passes in Greek or Latin, as well as law and history.[15] These requirements were in addition to the completion of five years of articles of clerkship.

The new rules of 1872 further revised the requirements for admission.[16] For admission as a barrister, a Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of Melbourne, or another recognised university, was compulsory (with some exceptions for overseas barristers). For attorneys, the usual requirements were matriculation at the University, five years’ clerkship and passing six examinations in law. However, candidates who had a degree in Arts or Law were excused the examinations and were required to serve only three years’ clerkship.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of the University of Melbourne in providing education for Victoria’s lawyers – both barristers and attorneys – from 1865 if not before. The University conferred 367 law degrees between 1857 and 1900 (although very few before 1865), and barristers (or future barristers) earned around 150 arts degrees from the University in that period.[17] In addition, many hundreds of articled clerks matriculated in the University before becoming attorneys. This reliance on the University is evident in the many hundreds of certificates it conferred that are contained in the admission files.

Demographics of the profession

At this stage I have completed basic demographic analysis of barristers only. I will be undertaking a similar analysis of attorneys, and barristers and solicitors in the near future.

Sex and age

All lawyers admitted to practise in Victoria between 1841 and 1900 were men; women were not permitted to practise until 1903.[18]

Candidates for admission had to be at least 21 years old.[19] Admission documentation discloses dates of birth (and hence the basis to calculate age at admission) for only 63 barristers (other than those first admitted in the UK). The mean age at admission for those 63 barristers was 26 years and the median 25, with a range from 21 to 47 years.

Ancestry

Candidates for admission had to be British subjects (natural-born or naturalised).[20] While that requirement did not preclude men of any ancestry being admitted, in fact all lawyers admitted to practise in the nineteenth century were of European ancestry.[21]

I have attempted to determine the specific ancestry of each barrister using information on birthplace and surname.[22] Although complete accuracy is not realistic without much further research, the data thereby obtained should suffice to provide useful estimates. (To keep the volume of research within reasonable bounds, only the barrister’s male lineage was considered in determining ancestry.) Of the 402 barristers for whom ancestry could be determined with reasonable certainty, the breakdown is as shown in the table below (percentages are rounded and so may not add to 100).

|

Ancestry |

Number of barristers |

Percentage of barristers |

|---|---|---|

|

English |

227 |

56 |

|

Irish |

67 |

17 |

|

Scottish |

49 |

12 |

|

Welsh |

7 |

2 |

|

Other British Isles |

3 |

1 |

|

British Isles (ambiguous) |

34 |

8 |

|

Subtotal – British Isles |

387 |

96 |

|

Jewish |

6 |

1 |

|

German |

5 |

1 |

|

Other European |

4 |

1 |

|

Total |

402 |

100 |

The ‘Irish’ category intends to exclude the Anglo–Irish (who are counted as ‘English’ in this analysis), but where the ancestry is uncertain and there is a clear Irish connection, the individual has been counted as ‘Irish’. This has likely resulted in a slight overstatement of the numbers of ‘Irish’ in these figures. The category ‘British Isles (ambiguous)’ comprises individuals with a surname native to more than one of the countries of the British Isles, and for whom no birthplace information was available.

Possibilities for further research

I will soon complete collection of data on attorneys, and barristers and solicitors, and then undertake the additional analysis of admissions and demographics noted above. This will provide much richer data on the profession overall and enable comparisons to be made between barristers and attorneys for the period prior to 1892.

Anyone who is researching an individual who practised law in Victoria can benefit by looking at the relevant admission documents. In the large majority of cases, the documents will provide at least a little illumination on the lawyer’s background. In many cases there is much more, with crucial data on birth, parentage, education, pre-law career and migration to Victoria. The character reference and the records of clerkship provide information on the lawyer’s circle of professional acquaintances prior to admission. The records discussed here do not provide information on the areas of law practised by the lawyers, so such information would need to be sought elsewhere.

Obviously the records would be valuable for anyone researching the legal profession in Victoria in the nineteenth century. However, in the absence of data summarising the records’ contents, the task of working through the many individual files is very substantial. It is my hope that the data obtained from the records and made available as described at the beginning of this article will assist in that regard.

Endnotes

[1] Each practitioner in this branch was admitted as an ‘attorney, solicitor, and proctor’. This threefold denomination is a reflection of English practice in the early nineteenth century: attorneys practised in courts of common law;solicitors in courts of equity; and proctors in ecclesiastical courts. While these differing jurisdictions were exercised by different courts in England, the Supreme Court of Victoria had been invested at its creation with all three jurisdictions (legal, equitable and ecclesiastical), and until 1892 the titles of its practitioners reflected this combination.

[2] In official documents of the nineteenth century, barristers are called ‘esquires’ while attorneys are granted the lesser designation of ‘gentleman’. In some English-speaking countries with a fused profession, including the contemporary United States, all lawyers enjoy the formal designation of ‘esquire’.

[3] Legal Profession Practice Act 1891 (Vic.), especially sections 3, 4 and 10.

[4] PROV, VA 914 Supreme Court of NSW for the District of Port Phillip (1841–1852) and VA 2549 Supreme Court of Victoria (1852–), VPRS 16236/P1 Roll of Barristers, unit 1; VPRS 16237/P1 Roll of Attorneys, unit 1.

[5] To avoid a power vacuum, it was provided that the Supreme Court of New South Wales continued to have jurisdiction in Victoria after Separation until the establishment of the new Colony’s own Supreme Court: Australian Colonies Government Act 1850 (Imp.), section 28. Similarly, some public officers (including justices of the peace) of the Government of New South Wales continued to exercise power in Victoria until they were superseded or dismissed: Victorian Public Officers and Magistrates Act 1851 (NSW).

[6] An Act to make better provision for the administration of justice in the Colony of Victoria (Vic., 1852), section 2. The right of practitioners admitted to the preceding court to practise in the new court without further formality is established by section 8 of the Act.

[7] Supreme Court Act 1915 (Vic.), section 6. See now Constitution Act 1975(Vic.), section 75(1).

[8] Although the PROV series VPRS 82 has only 20 units, there are a number of sub-boxes numbered 1A to 1F in unit 1.

[9] The letters used are G for Gray’s Inn (London), I for the Inner Temple (London), K for the King’s Inns (Dublin), L for Lincoln’s Inn (London), M for the Middle Temple (London) and S for the now-defunct Serjeants’ Inn (London).

[10] This does not seem to have been stated explicitly until 1865, when new admission rules were made: ‘Rules of the Supreme Court of Victoria’, chapter II, part I, rule 8, Victoria Government Gazette, 19 January 1866, p. 137. However, this applied only to barristers; no equivalent explicit rule was in place for attorneys, although it is clearly implied by other rules.

[11] The data used in the chart for ‘colonial barristers’ include a very small number of barristers admitted in other Australian colonies, one in New Zealand and one in Canada. There was also a single barrister admitted who had previously been admitted in Scotland as an advocate; he is not included in the data used for the chart.

[12] ‘Rules and regulations for admission to practise as barristers, and as attorneys, solicitors, and proctors, in the Supreme Court of the Colony of Victoria, of persons not previously admitted as barristers or advocates, or as attorneys, solicitors, or Writers to the Signet, in the superior courts of Westminster, Dublin, and Edinburgh’ (hereinafter ‘Rules and regulations for admission’), rule IX – Subjects on which candidates are to be examined,Victoria Government Gazette, 27 April 1853, p. 597. The admission requirements were essentially unchanged in the codification of court rules of 1854.

[13] ‘Rules and regulations for admission’, rule XIII – Examination of such candidates [that is, for attorneys], p. 597.

[14] ‘Rules of the Supreme Court of Victoria’, chapter II, part I, rule 23, Victoria Government Gazette, 19 January 1866, p. 137.

[15] ibid., part II, rule 36, p. 137.

[16] ‘Rules of the Supreme Court of Victoria’, chapter II, part I, rule 9, Victoria Government Gazette, 6 June 1873, p. 999.

[17] Figures are from the author’s personal data sets of Australian university graduates from 1856 to 1900.

[18] The first woman admitted to practise law in Victoria – and Australia – was Grata Flos Matilda Greig (1880–1958), who was admitted in 1905 and practised as a solicitor. The Parliament of Victoria passed the Legal Profession Practice Act 1903 (Vic.), which allowed the admission of women, at the instigation of Greig and her friends: Ruth Campbell and J Barton Hack, ‘Greig, Grata Flos Matilda (1880–1958)’, Australian dictionary of biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1983, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/greig-grata-flos-matilda-7049/text11103>, accessed 3 May 2014.

[19] ‘Rules and regulations for admission’, rule VI – Qualification of candidates not previously admitted, p. 597. This requirement was repeated in the new admission rules made through to 1900.

[20] ibid. This requirement also was repeated in the new admission rules made through to 1900.

[21] William Ah Ket (1876–1936), born in Victoria to Chinese parents, was admitted in 1903 and practised as a barrister from 1904. He seems to have been the first person of non-European ancestry admitted to practise law in Victoria: John Lack, ‘Ah Ket, William (1876–1936)’, Australian dictionary of biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1979, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/ah-ket-william-4979/text8267>, accessed3 May 2014.

[22] The reference used to identify origins of surnames was P Hanks and P Hodges, A dictionary of surnames, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1988. Birthplace was obtained when possible from admission documents, and otherwise from the Australian dictionary of biography where it had an entry for the individual. I was unable to determine ancestry for 20 of the 422 barristers.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples