Last updated:

‘Maroondah Reservoir Park: the creation of a monumental landscape’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 13, 2014. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lee Andrews.

This is a peer reviewed article.

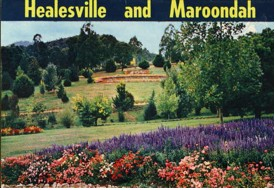

This article reveals the previously little-known early history of the Maroondah Reservoir Park, which was developed after completion of the Maroondah Reservoir in 1927. Located approximately seventy kilometres east of Melbourne, Maroondah Reservoir was an experiment. Not only was it the first reservoir constructed by the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW), established in 1891, but it was the first built under its somewhat contentious closed catchment policy. This policy offset prohibition of public access to water catchments with provision of adjacent landscaped public parkland. The development of attractive and publicly accessible parkland as an adjunct to the reservoir was thus central to the success of the venture. What was achieved at Maroondah Reservoir was the creation of one of the most impressive landscapes – indeed a ‘monumental landscape’ – ever designed for public purposes in Victoria. Maroondah Reservoir Park became the MMBW’s showpiece public garden, and its success made it the model for all of the MMBW’s subsequent reservoir parks.

Documentary records held by Public Record Office Victoria provided detailed accounts of formative landscaping works in the park and yielded new insights into many aspects of the park’s development over the past almost 90 years. Significantly, they revealed the previously unknown fact that Hugh Linaker, one of Victoria’s foremost landscape designers and tree planters in the 1920s and 30s, was responsible for the impressive tree collection still enjoyed by visitors today. These records played an important part in assessing Maroondah Reservoir Park as being of historic, aesthetic, social and scientific importance to the State of Victoria.

Introduction

After a century of service, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) was dismantled in 1991 and replaced with a new public body, Melbourne Water Corporation. Management of public assets which had been built up over more than a century, including Melbourne’s water supply, catchments and waterways thus became its responsibility. Appropriate management of these assets requires a detailed understanding of their history and the extent and nature of the heritage values they may embody. To this end, in 2010 Melbourne Water commissioned Context Pty Ltd to prepare a conservation management plan for the Maroondah Water Supply Scheme, including Maroondah Reservoir and Maroondah Reservoir Park.[1] This article draws on research, undertaken by the author for Context, into the history of Maroondah Reservoir Park and assessment of its heritage values.[2]

Beginnings of the Maroondah Scheme

Maroondah Reservoir is located in the upper reaches of the Yarra Valley, approximately seventy kilometres east of Melbourne. It was completed in 1927, but planning for the reservoir stretched back half a century. Melbourne’s reticulated water supply began in 1857, with the completion of the Yan Yean Reservoir, which drew water from the Plenty Ranges to Melbourne’s north. With minimal augmentation the Yan Yean system served the growing city for many years. As Melbourne’s population rapidly increased, additional water sources were explored, and in the early 1870s the Watts River and other tributaries of the Upper Yarra were identified as being the best additional sources of water.[3] In 1872, the Watts River watershed was permanently reserved in readiness for future works.[4]

Following a detailed survey of the Watts River in 1880 a diversion weir and later a dam on the river were planned. This would become known as the Watts River Scheme. In February 1891 the Governor of Victoria, the Earl of Hopetoun officially opened the first stage of the scheme – the weir on the Watts River. At the ceremony the governor re-named the scheme, proclaiming ‘I christen the new stream by the native name of Maroondah.’[5] Thus the ‘Maroondah Scheme’ was born.

In the same year (1891) the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) was formed to build and maintain the city’s sewers and water supply. It would be responsible for this for the next century.

‘The public health is my reward’ – the Closed Catchment Policy

When the MMBW was formed it adopted the motto ‘The public health is my reward’. In order to protect the health of the public, the purity of the water supply was paramount. To achieve this the MMBW’s predecessor, the Water Supply Board, adopted what became known as the closed catchment policy in the latter part of the nineteenth century.[6] This somewhat contentious policy prohibited logging, farming, settlement or indeed any human activity within catchment areas.[7]

To implement the policy, drastic action was sometimes required. In the Watts River catchment, for example, the government compulsorily acquired all private land between 1885 and 1891. This included the entire township of Fernshaw, which had all its buildings moved elsewhere or demolished.[8] At this time Melbourne was one of only five cities in the world with protected water catchments.[9]

A decision is made to build a massive structure

In the early twentieth century, population increase and episodes of drought put further pressure on Melbourne’s water supply, and the MMBW eventually decided to proceed with construction of the dam, postponed since the 1880s, downstream of the Watts River weir. This was the beginning of the most significant expansion of the water supply system since the construction of the Yan Yean system.[10]

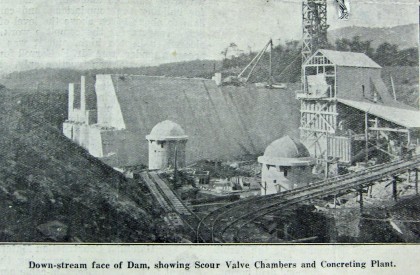

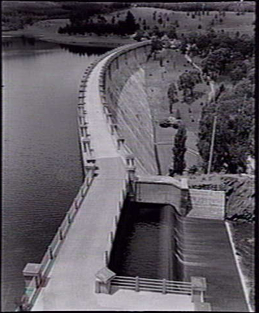

Delayed by World War I, tenders were finally called for the construction of the ‘Maroondah Cyclopean Rubble and Concrete Dam and Outlet Tower’ in 1920. The lowest of five tenders, submitted by E Carroll, was accepted by the MMBW on 5 October 1920.[11] Construction commenced shortly thereafter. The Argus had proclaimed some months earlier that Maroondah Dam would be a massive structure and the largest dam built in the history of the MMBW.[12] It would also be the first reservoir to be built under the closed catchment policy.[13]

Maroondah Reservoir – a closed catchment experiment

In constructing Maroondah Reservoir under the closed catchment policy, the MMBW was embarking upon an experiment. Here for the first time the MMBW planned to construct a reservoir whose vast catchment would be closed to the public from the very outset. The catchment area had been popular for outdoor recreation since the nineteenth century, and the nearby town of Healesville was an established tourist centre. Given the contentious nature of the closed catchment policy and the possibility of a public backlash against the MMBW, careful planning was necessary.

The MMBW undertook to compensate the public for their loss of access to the catchment by creating for them a splendid, landscaped replacement. The development of attractive and publicly accessible parkland as an adjunct to the new reservoir would thus be central to the success or otherwise of the venture.

The MMBW had previously carried out retrospective planting in older reservoir reserves at Yan Yean and Touroorrong, and at the Wallaby Creek weir, not only to make them more attractive to visitors but to prevent erosion of the banks.[14] At Maroondah however, the MMBW planned the development of a landscaped public park as an integral part of the overall project. Maroondah Reservoir, as the Board’s first reservoir constructed under its closed catchment policy, was to set the example for all that would follow.

A fine tourist attraction

The long-awaited commencement of the dam’s construction in 1920–21 aroused considerable public interest and became an added ‘engineering’ attraction in an area long valued for its scenic and natural qualities. The surrounding mountainous country and the township of Healesville had been initially developed for timber-cutting and milling. The subsequent reservation of these forests as protected catchments for the Yarra River and its tributaries closed many timber mills, to the detriment of the local economy. However, the perceived association between clean mountain air and physical and moral health during the latter nineteenth century led to the gradual re-development of the area as a popular tourist resort. Its proximity to Melbourne made it ideal for day trippers, with travel considerably facilitated by the arrival of the railway in the late nineteenth century.[15]

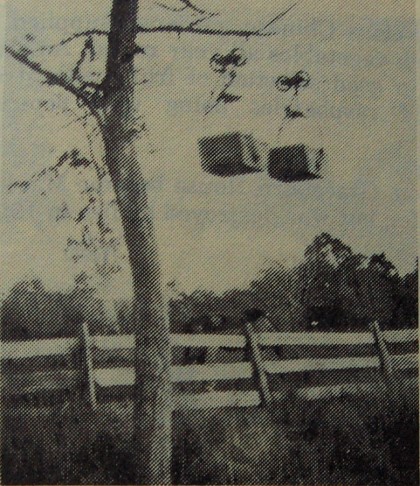

The dam construction and the aerial ropeway, which transported construction supplies from Healesville Railway Station to the dam site, were both popular drawcards. Many visitors to Healesville made a point of following the dam’s progress, and visits to view the dam and ropeway were popular outings. It was not only tourists who enjoyed these engineering spectacles. In 1922, the Governor-General and Lady Forster visited the construction works and the aerial ropeway,[16] as did Lord Stradbroke and the Countess of Stradbroke in 1925.[17]

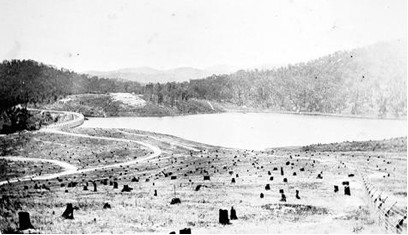

Throughout the 1920s the Argus followed the dam’s progress, and on 26 August 1926 it reported that water had begun flowing into the dam, and the reservoir was filling rapidly.[18] The attractions of the area, including the dam’s construction, were also energetically promoted by the Healesville Tourist and Progress Association (established 1904), and in 1926 it suggested to the MMBW that the Maroondah Dam should be renamed ‘Maroondah Reservoir’ or ‘Maroondah Weir’.[19] The MMBW Water Supply Committee supported this suggestion.[20]

A month later, the Argus reported on the remarkable public interest in the reservoir:

Healesville: Ideal holiday weather prevailed during the Christmas holidays. Nearly 3000 persons arrived by train from Friday until Monday, and the road traffic was exceptionally heavy. The new Maroondah reservoir has been visited by hundreds of tourists, who have expressed their wonder at the magnitude of the work and the expanse of water amid charming scenery.[21]

‘A true picture of Dante’s inferno’

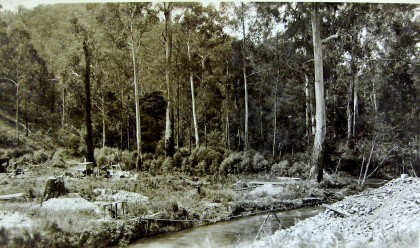

Prior to the construction of the Maroondah Reservoir the entire catchment area was densely forested with eucalypts, native pines, wattles and tree ferns.

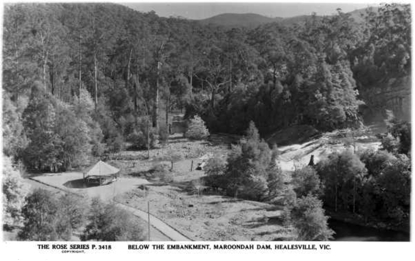

While construction of the dam required timber to be cleared from the valley prior to flooding,[22] the area downstream of the dam wall was largely untouched, with the intention of creating a parkland for the visiting public.[23]

Unfortunately, despite the MMBW’s policy of carefully retaining indigenous vegetation where possible, the site was dealt a bitter blow when, in February 1926, bushfires burnt out much of the valley floor behind the dam wall and the hillside to its east. The ‘Maroondah Dam flat’ was described at this time as a ‘true picture of Dante’s inferno’.[24] Large-scale replanting was urgently needed, both for reasons of aesthetics and water-quality.

Designing an enclosure for the public

From the outset, a park had been planned for Maroondah Reservoir to allow tightly-controlled public access while protecting the pristine nature of the catchment area. The language used by the MMBW Water Supply Committee in its meetings, and recorded in its minutes, is very revealing. The park being created at Maroondah Reservoir was repeatedly referred to as ‘the public enclosure’, especially while initial landscaping, fencing and other improvements were being carried out. Clearly, the MMBW saw its task as providing beautiful surrounds for the public, who would be kept firmly behind fences and locked gates and excluded from the catchment area. Indeed, this was spelt out quite clearly by the Water Supply Committee’s engineer Edgar Ritchie, in a memo of 2 June 1926. In describing two alternative exclusion fencelines around Maroondah Reservoir, he noted:

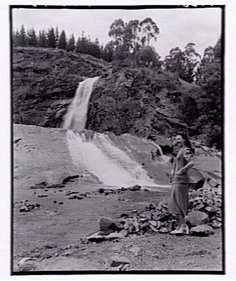

In so far as the public are deprived of … sight seeing, which they had on the old track to Maroondah Weir and Mathinna Falls (which would be excluded with either fence) they will have a very much finer sight seeing provision in the reservoir itself. If the area … be suitably planted out and provided with a few water taps and fireplaces, it can be made a very attractive place for sight seeing and picnics, and the Board should commence the work of planting in this area, which has been well burnt out, during this winter, choosing trees which will be suitable for the purposes above mentioned.[25]

This approach was also explicitly stated by the MMBW in a retrospective article on the construction of the Maroondah Reservoir written in 1957:

It would be so convenient, after completing a starkly utilitarian project such as this, to leave the scars of man’s operation on the earth to heal themselves. But when the Board of Works embarks on such works its policy is to leave the land more beautiful, if possible, than it was before. While it is necessary, in the interest of the city’s health, to exclude the public from the catchment area, the vicinity of the dam itself can be easily supervised. And since this great engineering work belongs to the people, the Board makes it available to the people as a place for recreation. It has created here a parkland that any city in the world might envy.[26]

Planting Maroondah Reservoir Park

In beautifying the new reservoir park, the first task was to develop a planting plan. For this task, in March 1927, the Water Supply Committee called on Ritchie,[27] and in July he submitted a ‘scheme with regard to the planting of trees outside the exclusion fence at the Maroondah Reservoir’ (that is, in the park) and a plan showing the distribution and general layout. The planting, as detailed in his plan, and costing £250, was approved by the Committee.[28] Unfortunately, these plans were not found in the PROV records that were consulted.

While this suggests that Ritchie was responsible for the tree-planting which resulted in much of the spectacular treescape seen in the park today, a further reading of the minutes tells a different story. They reveal a previously unknown fact – that Hugh Linaker, expert tree planter and the leading landscape designer of his generation, was closely involved in this initial phase of tree-planting within the public park.[29]

The first mention of Linaker’s involvement appears in the minutes of 10 August 1927, shortly after Ritchie submitted his planting scheme to the committee. Here Ritchie recommended that letters of thanks be sent to ‘Messrs Linaker and Railton’[30] for assistance rendered by them in regard to the question of tree planting on the MMBW’s reservations, outside the exclusion fence (that is, inside the public park) at the Maroondah Reservoir.[31] While Railton was not mentioned again in subsequent minutes, Linaker’s close involvement with planting in the park was noted over the course of the next fifteen months.

The minutes record that initial planting of the public area was carried out from August to November 1927.[32] This plantation was then inspected by Linaker in April the following year, leading him to recommend certain replacement trees and even offering to prune the trees ‘this season’.[33] In June 1928, further ‘ornamental planting’ was proposed and Linaker was thanked for procuring the trees.[34] In October 1928 Linaker provided a report to the Water Supply Committee stating that he had inspected ‘both plantations’ and they were generally doing well. The minutes also reveal a cost of £198.16.0 for trees supplied, presumably by Linaker, who had an impressive nursery from which to distribute plants.[35] In November the Water Supply Committee minutes record the committee’s appreciation of his assistance, and clearly suggest that Linaker had assisted in planting within both the public area and the catchment area.[36]

It is therefore clear that Hugh Linaker was integrally involved with the formative development of the tree plantations in Maroondah Reservoir Park. Between August (and possibly earlier in March) 1927 and November 1928 Linaker advised Ritchie on tree selection, procurement and planting. Linaker inspected the plantations and personally pruned trees in the downstream (publicly accessible) section of the park and probably supplied the tree stock.

No mention is made in the Water Supply Committee minutes of the specific trees planted, and the MMBW annual report for 1928–1929 indicates only that

[a] considerable amount of planning has been devoted to making the surroundings of the Maroondah Reservoir attractive, so that the public could have access to visit certain parts of the works … A very large number of deciduous and other trees have been planted and most of these are growing well.[37]

The Water Supply Committee minutes also fail to reveal how Linaker came to be involved in the planting program. They do however indicate a very close relationship between the committee and the Victorian Tree Planters’ Association (VTPA), of which Linaker was a founding member. The minutes suggest that, as a consequence of sending a representative to the VTPA annual conference in March 1927, the MMBW instructed Ritchie to prepare a report for large-scale replanting in the MMBW’s watershed areas. At the same time, he was also instructed to submit a planting scheme for the Maroondah Reservoir Park.[38] One of the conference’s keynote speakers was Hugh Linaker, and his presentation at the conference regarding tree planting was directly relevant to these matters and apparently highly influential.[39]

Hugh Linaker – the leading landscape designer of his generation

In its quest for developing ‘a scheme … for planting trees with good foliage of various kinds’,[40] the Water Supply Committee could have found no better practitioner than Linaker.

Hugh Linaker (1872–1938) was a landscape gardener, horticulturist and ‘tree planter’. His horticultural career began as an apprentice at Ballarat Botanic Gardens around 1886,[41] after which he was appointed Curator of Parks and Gardens for the municipality of Ararat in 1901.[42] Following his widely praised transformation of Alexandra Park (originally Ararat Botanic Gardens), he was appointed Landscape Gardener, Hospital for the Insane at Mont Park in 1912. Here he was responsible for landscaping the grounds of the new hospital (opened in 1911). During his tenure there he undertook new or improved landscaping works at all the other Hospitals for the Insane in Victoria, including Yarra Bend, Kew, Ararat, Beechworth, Sunbury, Ballarat, Royal Park and the Kew Idiot Asylum. He also supplied many thousands of plants to other institutions from the impressive nursery he had established at the Mont Park Hospital from 1913.[43]

Linaker was a frequent lecturer and as an inaugural member of the VTPA, which was formed around 1924,[44] sought to address (in part) the need for increased tree planting and provision of public parks in urban areas. The VTPA became a centralised source of practical tree-planting knowledge, which it then disseminated to its members and the community.[45] The association became an influential advisory body, and its annual conference was a pivotal event for members.[46] As a member of the VTPA Linaker was involved in the creation of the Mount Dandenong Arboretum in 1928.[47]

Linaker was keenly interested in tree-planting projects on main highways, and his advice was sought by many municipalities for the planning of public parks and gardens. According to the Argus, by the time he was appointed State Superintendent of Parks and Gardens in 1933, Linaker had laid out ‘school grounds throughout the State, plantations at the Buchan caves [1930] and Mount Buffalo National Park [1920s], gardens at the police depot in St Kilda road, and at Pentridge and at nearly every other penal settlement in Victoria, the gardens at Stonnington and the Government cottage at Mount Macedon’.[48]

Linaker was engaged by Sir John Monash, a former chairman of the State Electricity Commission, to advise on the planning of the model township at Yallourn (1925–1931), and was involved in the Yarra Boulevard beautification and the planting of the Yarra Bend National Park (1930).[49] In a private capacity Linaker also provided input into both the city and country gardens of Alfred Nicholas – Carn Brea, in Hawthorn (1928), and Burnham Beeches, in the Dandenongs (1930–1934).[50]

Between 1933 and his death in 1938 Linaker prepared plans for the improvement of the Kings Domain and planting at the Shrine of Remembrance.[51] The Argus also observed that the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Gardens (1934), ‘with their novel departures from orthodox landscape work, were entirely [Linaker’s] conception’.[52]

When he died in 1938 at his home in Hawthorn, Linaker was regarded by many as the leading landscape gardener of his generation in Victoria.

Linaker’s grand forest landscape

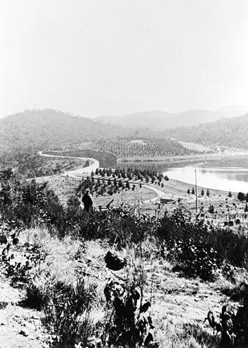

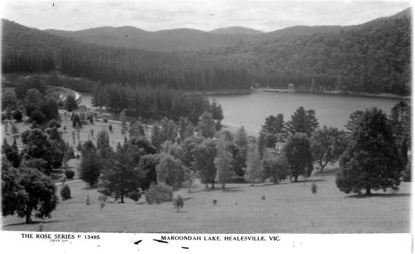

While no plan showing the extent of Linaker’s planting works has been found to date, early photographs of the dam surrounds of Maroondah Reservoir show the devastated area with which he had to work (see photograph earlier in this article taken circa 1927). Bushfire and construction activity had destroyed much of the native vegetation, except for some surviving eucalypts along the river bank and scattered on the hillsides. Thus Linaker had an opportunity to improve on what had been before.

Despite the devastation, the broad valley floor behind the dam, the rising monolithic structure of the dam wall, the tumbling waterfall of the cascading spillway running into the Watts River, all ringed by the distant hills of the catchment, provided a splendid backdrop for new planting. Perhaps these features brought to Linaker’s mind the broad glacial valley of Yosemite in California, with its monolithic rock formations, cascading waterfalls, and meandering Merced River. Indeed, Yosemite Valley had been evoked by the nearby area, which had once housed the tiny township of Fernshaw.[53] A retrospective piece written in the Argus described it thus:

The little hollow of the hills in which every possible natural beauty (except the ocean) seemed focused. Mountains; the most wonderful trees, recalling those of the Yosemite Valley; inexhaustible gullies of choicest ferns; the most beautiful and varied foliage; purest air, and the constant soothing murmur of streams and runnels.[54]

Many of Linaker’s favoured trees derived from the majestic landscapes of North America, and thus admirably suited the spectacular surrounds. In this splendid natural setting, Linaker set about replanting ‘idealised nature’ for the visiting public.

At Maroondah Reservoir, Linaker’s tree planting dominated the parkland. The hallmark of Linaker’s landscape designs was his use of a favoured palette of tree species, chosen for their individual qualities, and combined in unusual ways. Where allowed full expression, as occurred at Maroondah, the result was a spectacular forest landscape.

Interestingly, Linaker’s affection for certain tree species was not based solely on their landscape qualities. Unusually for the time, many of his favoured ornamental species were also valued for their timber, and Linaker argued that in any planting program this commercial consideration was important, regardless of whether the trees were to be planted for shade, shelter or ornamental effect.[55] Thus a number of Linaker’s favoured species, such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) were also fine timber trees.

In Linaker’s designs, contrast was paramount. By using contrasting tree forms (upright and spreading), foliage (colour, texture and shape), bark (texture and colour), tree origin (exotic and native) and seasonal character (evergreen and deciduous), Linaker produced visually stunning results.

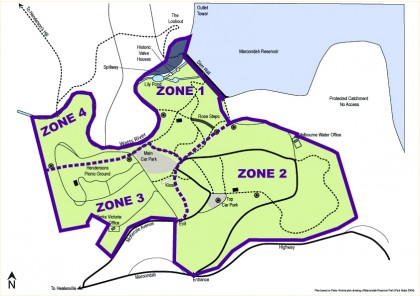

At this time, Maroondah Reservoir Park was approximately half its present size, and Linaker’s planting scheme was carried out in what is referred to in the plan below as zones 1 and 2.

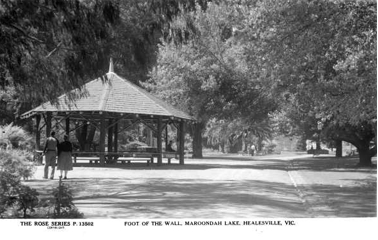

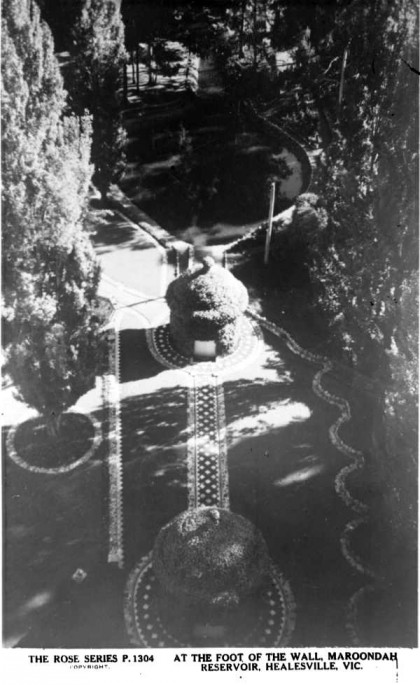

At the base of the dam wall (in zone 1), for example, trees such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Lombardy Poplar (Populus nigra var. italica) and Italian Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens) today dominate this awe-inspiring space and reinforce the visual dominance of the monumental concrete dam wall. Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) and Liquidamber or Sweet Gum (Liquidambar styraciflua) provided further contrast through their impressive autumnal foliage.

![‘Autumn scene below the [dam] wall at Maroondah’, circa 1955.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/AndrewsLR-F08-420x275.jpg)

Further downstream of the dam wall, Linaker planted spreading shade trees, contrasting evergreens such as Cedar (Cedrus spp.) with deciduous species of Ash (Fraxinus spp.), Elm (Ulmus spp.) and Oak (Quercus spp.). Linaker created further visual interest by adding the vertical forms of Cypress (Cupressspp.), Canary Island Date Palm (Phoenix canariensis) and Chinese Windmill Palm (Trachycarpus fortunei), as well incorporating tall, slender specimens of indigenous Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans) growing along the Watts River. Retention of indigenous trees, often carefully interplanted with exotic species, was part of Linaker’s trademark style, and thus at Maroondah he was able to incorporate into his design those indigenous trees which managed to survive the 1926 bushfires.

On the surrounding barren hillsides and rocky banks (zone 2) Linaker planted conifers – a device popular amongst the landscape designers working in the National Parks Service in the USA at the time. Early photographs give some idea of the extent of the planting (compare the photograph taken circa 1927 earlier in this article with the next two images below) and Linaker’s cypresses and pines continue to dominate these particular locations even today. A large number of Monterey Cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) were planted throughout the park as shelter belts, individual specimens, and as a partial avenue along the entry road. Linaker also planted fine specimen conifers, including one of his signature trees – the Upright Monterey Cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa‘Fastigiata’); Smooth Arizona Cypress (Cupressus glabra) – another Linaker favourite chosen for its bluish foliage and red peeling bark; and the rarely planted Blue or Himalayan Pine (Pinus wallichiana) featuring obvious bluish needles which form a striking contrast to a nearby copse of Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis). Other favourites planted include Upright Lawson’s Cypress (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana ‘Fastigiata’) and the fine timber tree Douglas Fir, also known as Oregon (Pseudotsuga menziesii).

In addition to Linaker’s tree collection, the park contains a number of individual trees particularly notable for their rarity, unusual form, or as especially fine examples of their species. These are

- Upright Monterey Cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa ‘Fastigiata’)

- Smooth-barked Apple (Angophora costata)

- Smooth Arizona Cypress (Cupressus glabra)

- Blue or Himalayan Pine (Pinus wallichiana)

- Cork Oak (Quercus suber)

- Fried or Poached Egg Tree (Polyspora axillaris (Synonym: Gordonia axillaris))

- Cottonwood (Populus deltoides)

- Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)

- Lombardy Poplar (Populus nigra var. italica)

- Liquidamber or Sweet Gum (Liquidambar styraciflua)[56]

Linaker repeatedly employed these stylistic devices throughout his many designed landscapes, including Mont Park Psychiatric Hospital where, as its inaugural landscape designer and curator from 1912, he laid out its expansive grounds. They were also repeated two years after his involvement in Maroondah Reservoir Park, when he drew up a planting plan for the valley at Buchan Caves. The resultant landscape seen along the valley floor and hillsides of the Buchan Caves reserve today bears a remarkable resemblance to that of Maroondah Reservoir Park. The existence of Linaker’s annotated design for the Buchan Caves site, and the survival of associated documents, provide considerable insight into Linaker’s landscape philosophy.[57]

Some years later, Linaker again made effective use of his trademark fastigiate tree species in his designed landscape for the Shrine of Remembrance. In this location, favourites such as Lombardy Poplar (Populus nigra var. italica), Bhutan Cypress (Cupressus torulosa), and the Australian native Kauri (Agathis robusta), provided a strong vertical dominance.

Planting in the catchment

Linaker was also involved with remedial planting which was undertaken outside Maroondah Reservoir Park, upstream of the dam wall and within the catchment zone. As a result of the 1926 bushfires which had devastated the MMBW’s water catchments, including Maroondah, the organisation adopted a new forestry plan in early 1928. A comprehensive reforestation program, to which Linaker undoubtedly contributed, formed part of the plan and included some tree species Linaker had also planted in the public park, such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and Eastern or Plains Cottonwood (Populus monilifera – now Populus deltoides subsp.monilifera).[58]

Records show that by June 1932 almost 6000 trees and 79 shrubs had been planted throughout the reserve (presumably both upstream in the closed catchment and downstream in the public park).[59] As the only planting referred to in the relevant MMBW minutes was that undertaken in 1927 and 1928 under Linaker, these tree statistics undoubtedly reflect his work.

Tourism flourishes

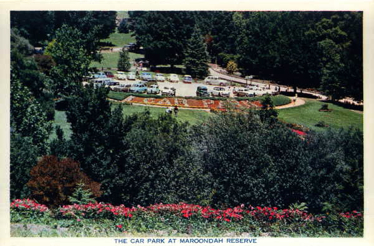

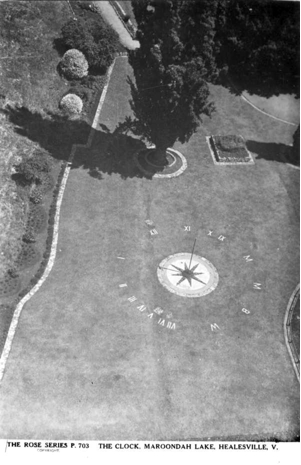

With the ornamental tree planting complete, further landscaping works were undertaken. Initially these were modest and utilitarian in nature and comprised fencing, paths, roadway, car park, and brick ‘sanitary conveniences’. Two caretakers’ dwellings were also constructed. With the almost meteoric rise in the popularity of the reserve it became clear that more facilities would be required. The ‘few water taps and fireplaces’ suggested by Ritchie in mid-1926 would not be sufficient for the hordes of tourists. In 1928, a year after the completion of Maroondah Reservoir, Healesville was the most popular tourist destination in Victoria, with 10,000 people visiting the town in the holiday period.[60] Healesville’s popularity ensured a constant flow of visitors to Maroondah Reservoir,[61] and the spillway provided an exciting natural spectacle in the winter and spring, when the water flow was at its greatest.

By 1932 two shelters and a ‘kiosk’ with hot water for visitors had been constructed, and Maroondah Reservoir Park quickly became an established tourist attraction. From the 1930s Maroondah Reservoir featured in countless postcard views, the earliest of these being sold at the newly-built kiosk within the park from 1931.[62]

The MMBW took great pride in the appearance of its water supply landscapes. The MMBW’s annual report for 1960–61 included a full page image of the outlet tower at Maroondah Reservoir under the caption ‘Functional Beauty’ with the following comment:

The Board has long held the view that its structures – reservoirs, treatment plants, and even small suburban pumping stations – should be aesthetically attractive as well as functional. That the public shares in this view is shown by the ever-increasing number of visitors to the Board’s works.[63]

At Maroondah Reservoir this philosophy is clearly evident. The outlet tower, completed around 1925, was designed in an elegant Classical style, probably by Ritchie, with designing draftsman HA Wood.[64] It was the subject of countless photographs, being also used by the MMBW to promote the park.

The concrete balustrade flanking both sides of the pedestrian path across the top of the dam wall was finished with decorative pyramidal capping. On the floor of the park behind the dam wall, two valve houses were also designed in an aesthetically pleasing way (see the first photograph in this article).

A successful experiment

Ritchie retired in 1936, having been with the MMBW since its inception – a span of almost forty-five years.[65] In less than a decade, the experiment which was Maroondah Reservoir and its park had become a stellar success. Maroondah had become the MMBW’s ‘model’ reservoir, and its carefully designed public park a tourist destination not to be missed.

Because of the closed catchment policy, the Vice Chairman of the MMBW’s Water Supply Committee GS Walter could boast in 1936 that Melbourne’s water was among the ‘best and purest in the world’ and needed no filtering due to the great care taken to prevent pollution.[66] With Maroondah Reservoir and its park, the MMBW had demonstrated that, by following the model trialled at Maroondah, such a restrictive policy need pose no impediment to tourism or the enjoyment of the general public. Indeed, Maroondah Reservoir Park provided the visitor with a highly unusual experience – one which was unavailable in the public parks and gardens in and around Melbourne at the time. Most of these had been developed in the nineteenth century, and comprised botanic gardens, municipal reserves or small inner-city garden ‘squares’. Maroondah Reservoir Park, in contrast, was a large public garden set in a forested mountain location, with qualities akin to a national park. The rare (and free) experience which it offered visitors undoubtedly contributed to its great popularity.

Over the next seven decades the landscape, so carefully laid out and planted by Linaker, would undergo many changes, and its popularity would continue to grow.

Consolidation of the landscape: World War II and beyond

During World War II (1939–1945) Maroondah Reservoir was closed to the public, but throughout this period and shortly thereafter landscaping continued. Comprehensive replanting of the Maroondah watershed, which was devastated by the catastrophic 1939 bushfires, was undertaken.[67] Fortunately the ornamental section of the park escaped the fires. Paths and extensive areas of stone paving, edging and guttering were constructed[68] and rotundas built using timber from nearby indigenous eucalypts which were cut into poles and split shingles.[69] The use of local stone and timber was not only cost-effective but was an expression of the prevailing ‘naturalistic’ landscape ideals of the time.

After World War II, the rise of car ownership and the popularity of the Sunday drive to Healesville helped cement Maroondah Reservoir Park as a tourist hub for the remainder of the twentieth century. During this time, the park would experience flights of landscaping fancy, where decorative ornamentation was taken to new heights. In contrast to the ideals of naturalism which guided the landscaping of the 1930s and 40s, now in the park the ‘hand of man’ could be seen everywhere.

The purchase of adjoining land around 1972[70] extended the area of the park, and in the 1980s changing landscape fashions and financial constraints resulted in simplification of the landscape. Much of the floral exuberance of the past was dismantled. With these changes, the landscape was effectively returned to its early form. Throughout this time, Linaker’s tree collection, and the early stonework and structures were respected and given due care. As an example, roses which flanked a flight of stone steps (known as the ‘Rose Steps’) constructed in the 1940s were replaced around 1980 with Golden Pencil Pines (Cupressus sempervirens ‘Swane’s Golden’).[71] Although not planted by Linaker, the strong vertical accent they provide reinforces the ‘monumental’ character of the landscape, and they are therefore consistent with Linaker’s original design intent.

During the Ash Wednesday bushfires in 1983, and again on Black Saturday in February 2009, large areas of forest in the Maroondah catchments were lost. Indeed on Black Saturday, one-third of Melbourne’s forest catchment was destroyed by bushfire. Remarkably, yet again, Linaker’s ornamental plantations were unaffected.

Conclusion

Today, Maroondah Reservoir Park stands as testament to the MMBW’s closed catchment policy for which it fought so hard and stalwartly defended for more than a century. By creating a splendid recreation area for the public as an integral part of its first closed catchment reservoir in 1927, the MMBW was in effect promoting its work throughout the State of Victoria. Maroondah Reservoir Park became a powerful advertisement, in living colour, for the MMBW’s experimental project. The immediate and spectacular success of the Maroondah Reservoir Park was a public relations triumph, and made it the model upon which all of the MMBW’s subsequent reservoir parks have been based.

At Maroondah Reservoir a monumental landscape was created in the closing years of the 1920s, with the magnificent forest landscape by Hugh Linaker as a central feature. This landscape was further augmented throughout much of the twentieth century by embellishments and ornamentation typical of their time, but always respectful of the spectacular landscape created between 1927 and the late 1940s. Today, Maroondah Reservoir Park remains a magnificent designed landscape which is surprisingly intact despite the inevitable changes which have occurred over more than 80 years of use. It remains today one of the most popular public parks in Victoria.[72]

The MMBW records held by PROV proved invaluable in providing new insight into many aspects of the park’s early development. Through the information held in these records, Maroondah Reservoir Park was assessed in 2010 as being of historic, social, aesthetic and scientific heritage significance to the State of Victoria.[73] With this new understanding, Melbourne Water is able to make informed decisions regarding the protection of significant elements within the Maroondah Scheme and to mitigate possible threats to those elements.

Changes to the integrity of the 1920s Linaker tree collection pose the greatest threat to the heritage of the park. Fire presents the most obvious and catastrophic danger, especially in the wake of the 2009 bushfires. Climate change poses a longer-term challenge to the continued health of the existing mature trees and will affect the species selection of future plantings. Similarly, failure to adequately plan for the appropriate and timely replacement of extant mature and senescent trees has the potential to threaten the tree collection as a whole. This is particularly important as much of the tree collection is of the same age. Decisions can now be made which will protect the monumental landscape of Maroondah Reservoir Park for future generations.

Endnotes

[1] With the dismantling of the MMBW in 1991, the management of the park was transferred to Parks Victoria in 1994, however it remains part of the overall Maroondah Water Supply Scheme and so was included in the conservation management plan.

[2] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan: Vol. 3B: Maroondah Reservoir Park Conservation Analysis’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010.

[3] H Doyle and T Dingle, Yan Yean: a history of Melbourne’s water supply, Public Record Office Victoria, Melbourne, 2003, p. 64.

[4] T Griffiths, Forests of Ash: an environmental history, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, p. 95.

[5] Both the Age (19 February 1891, quoting the Argus) and the Lilydale Express (21 February 1891) reported the events. The original sectional plans and contracts for the construction of the Maroondah weir and aqueduct are held at Public Record Office Victoria.

[6] The history of this policy is complex. A detailed explanation of its development can be found in Doyle and Dingle, Yan Yean, and Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010.

[7] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010, pp. 5 and 27.

[8] ibid., pp. 5 and 6.

[9] Melbourne Water webpage, available at <http://www.melbournewater.com.au/aboutus/historyandheritage/Pages/Our-history-a-timeline.aspx>, accessed 15 May 2014.

[10] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010, p. 11.

[11] PROV, VA 1007 Melbourne Water Corporation (known as Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works until 1992), VPRS 8598/P1 Board Minute Books, unit 27, book no. 27, 1920, meeting 760, p. 7890.

[12] In fact Maroondah Dam was the only dam the MMBW, formed in 1891, had constructed.

[13] Several smaller weirs had already been built by the MMBW in a closed catchment environment, such as the O’Shannassy Weir and various weirs of the Watts River (Maroondah) system, but the MMBW had constructed no large-scale storage reservoir until Maroondah.

[14] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010, p. 35.

[15] ibid.

[16] Argus, 25 February 1922, p. 20.

[17] Argus, 24 August 1925, p. 9.

[18] Argus, 26 August 1926, p. 9.

[19] Argus, 16 November 1926, p. 7.

[20] PROV, VA 1007 Melbourne Water Corporation, VPRS 8609/P6 Historical Records Collection, unit 35, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 35, p. 4089.

[21] Argus, 30 December 1926, p. 5.

[22] In September 1917 a contract for clearing the site for the Maroondah Reservoir was drawn up by the MMBW Water Supply Committee, specifying: ‘Total of contract areas to be cleared 485 acres of which 3/5 is clearing flush with surface and the balance the stumps may be left in’. See PROV, VPRS 8609/P28, unit 12, Seeger Collection (1841–1970), contract document for the clearing of Maroondah Reservoir drawn up by the Water Supply Committee.

[23] Susan Priestley, in her book Making Their Mark, Fairfax Syme & Weldon, Sydney, 1984, p. 221 states that ‘Forest trees were first cleared from the valley floor, some going into telegraph poles and firewood; some being retained to construct picnic tables, benches and shelters in the recreation reserve planned for a section of the dam shore.’, in Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010, p. 17.

[24] ibid. p. 62. Reports regarding bushfires in the Maroondah, O’Shannassy and northern watersheds were noted in the meeting of the Water Supply Committee on 10 March 1926, in PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 34, Minute Books : Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 34, p. 3621.

[25] PROV, VPRS 8609/P21, unit 431, file 26/3218, memo entitled ‘Fencing Maroondah Reservoir’, E Ritchie, 2 June 1926.

[26] Metropolis: the quarterly journal of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works, Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works, Melbourne, 1957, pp. 9 and 12, quoted in J McCann, ‘Melbourne Water Historic Places Report: A report of Melbourne Water and related places in the forests of the Central Highlands of Victoria’, prepared for the Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra, and the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Melbourne, November 1993, pp. 77–78.

[27] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 36, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 36, p. 4332.

[28] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 37, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 37, p. 4556.

[29] ibid., p. 4610.

[30] This undoubtedly refers to James Railton, a second-generation nurseryman, president and committee member of the Nurserymen and Seedsmen’s Association of Victoria, who was a founding member (with Linaker and others) of the Victorian Tree Planters’ Association, and was actively involved in the Mount Dandenong Arboretum and Geelong Road plantation scheme, as detailed in the entry by D Watson, ‘Railton, David Balderston (c. 1834–1892)’, in R Aitken and M Looker (eds), Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens, Oxford University Press in association with Australian Garden History Society, South Melbourne, 2002.

[31] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 37, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 37, p. 4610.

[32] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 38, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 38, p. 4892.

[33] ibid., p. 5151.

[34] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 39, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 39, pp. 5272–73.

[35] ibid., p. 5540.

[36] On 21 November 1928 Engineer Ritchie reported on the completion of the planting of the upstream side of the Maroondah Dam and the satisfactory manner in which the work had been carried out. As a result, Ritchie recommended that a letter of thanks for his assistance be forwarded to Linaker, and that he be paid a bonus of 20 guineas, as had been done in the case of the plantation on the downstream side of the dam. This was approved by the Water Supply Committee, as recorded in PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 40, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 40, p. 5614.

[37] MMBW Annual Report 1928/29, reproduced in McCann, ‘Melbourne Water Historic Places Report’, p. 77.

[38] For example, PROV, VPRS 8598/P1, unit 34, book no. 34, meeting 919, 15 February 1927, p. 10566, PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 36, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 36, 23 March 1927, p. 4333. By early 1930 the MMBW’s Superintendent of Forests, D Middlin, who answered directly to Ritchie, was an office bearer of the VTPA, however this occurred after Linaker’s recorded involvement with the tree-planting at Maroondah.

[39] Linaker delivered a comprehensive paper titled ‘Utility trees in Victoria’ and this was reported at length in The Australasian, 2 April 1927, p. 17.

[40] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 36, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 36, p. 4332.

[41] The Australasian, 2 April 1927, p. 17.

[42] R Aitken, ‘Linaker, Hugh (1872 – 1938)’, in Aitken and Looker (eds), Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens.

[43] ibid.

[44] The Australasian, 2 April 1927, p. 17.

[45] ibid.

[46] E Stewart, ‘Parks and Leisure Australia (1998 –)’, Aitken and Looker (eds),Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens.

[47] Richard Aitken Pty Ltd in association with Lee Andrews, ‘Dandenong Ranges Gardens Values Assessment’, prepared for Parks Victoria, 2004.

[48] Argus, 23 August 1933, p. 8.

[49] Argus, 11 October 1938, p. 2.

[50] R Aitken, ‘Linaker’.

[51] J Mulhauser, ‘Hugh Linaker, landscape gardener to the Lunacy Department: a unique position’, in Australian Garden History, vol. 20, no. 4, April/May/June 2009.

[52] Argus, 11 October 1938, p. 2.

[53] The site of the village remains today as the Fernshaw Picnic Ground.

[54] Argus, 23 June 1934, p. 9.

[55] ‘Utility trees of Victoria’ presented by Hugh Linaker at the third annual conference of the VTPA in Ballarat in March 1927, and reported in The Australasian, 2 April 1927, p. 17.

[56] An explanation of the importance of these individual specimens can be found in Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan: Vol. 3B: Maroondah Reservoir Park Conservation Analysis’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010.

[57] See Richard Aitken Pty Ltd in association with Lee Andrews, ‘Buchan Caves Reserve European Heritage Action Plan’, prepared for Parks Victoria, 2003.

[58] The other tree species listed as suitable species for reservoir catchments were Pinus insignis (later Pinus radiata or Monterey Pine), Pinus ponderosa (Ponderosa, Western Yellow, or Yellow Pitch, Pine), Pinus larica (probably Pinus nigra subsp. laricio or Corsican Pine), ‘[p]lus other hardy natives’, in theArgus, 29 February 1928, clipping in PROV, VPRS 8609/P21, unit 111, book of various newspaper cuttings, letters and memos 1927–1935, including details of the 1926 bushfires, suitable tree species for reservoir catchments, issues of forest protection, and so on.

[59] MMBW Annual Report 1932, in J McCann, ‘Melbourne Water Historic Places Report’, p. 77.

[60] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010, p. 37.

[61] MMBW Annual Report 1932, in J McCann, ‘Melbourne Water Historic Places Report’, p. 77.

[62] PROV, VPRS 8609/P6, unit 44, Minute Books: Water Supply Committee (1891–1978), book no. 44, p. 7068.

[63] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010, p. 21.

[64] ibid., p. 20.

[65] PROV, VPRS 8609/P23, unit 28, MMBW Annual Report 1936.

[66] Argus, 28 March 1936, p. 10.

[67] PROV, VPRS 8609/P23, unit 28, MMBW Annual Report 1939 and MMBW Annual Report 1940, see p. 5, in Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan, Volume 2: History’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010.

[68] Reported in J McCann, ‘Melbourne Water Historic Places Report’, p. 79. Peter Revell, National Parks ranger employed at Maroondah Reservoir since 1980, indicated that the stone construction in the stairway known as the ‘Rose Steps’ and elsewhere in the park was the work of two rockwork experts – ‘Chopper Chaplin’ and another whose name Peter could not remember, Peter Revell, personal communication with the author, 23 July 2010.

[69] Information provided by Maroondah Reservoir caretaker Harold Burton, in J McCann, ‘Melbourne Water Historic Places Report’, p. 79.

[70] Information Board at Maroondah Reservoir Main Car Park, 2010.

[71] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan: Vol. 3B: Maroondah Reservoir Park Conservation Analysis’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010.

[72] Melbourne Water webpage, available at <http://www.melbournewater.com.au/getinvolved/activities/Pages/Barbecue-locations.aspx#Maroondah>, accessed 16 May 2014.

[73] Context Pty Ltd, ‘Maroondah Water Supply System Conservation Management Plan: Vol. 3B: Maroondah Reservoir Park Conservation Analysis’, prepared for Melbourne Water, November 2010.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples