Last updated:

‘The battle for Bears Lagoon’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 15, 2016–2017. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Richard Turner

William Doody, who was born on the goldfields in 1855, selected land at Bears Lagoon when he was 18 years old with his father, Joseph Doody. The selections might have gone unremarked and followed familiar patterns of hard work, and success or failure depending on their skills, entrepreneurial abilities, or luck. However, that was not to be. The Doodys and neighbouring selectors became locked in conflict for many years with powerful pastoralist interests represented by squatter John Ettershank. The Doodys and a dozen or so other selectors had selected blocks of land that John Ettershank regarded as his own. It set off a long and bitter struggle recorded in great detail in the Department of Crown Lands and Survey (Lands Department) records now held by Public Record Office Victoria. These records reveal, at the ground level, the conflict between the great squatters and 'liberal' governments, and between the selectors and the squatters themselves, illustrating the history of the struggle over land in Victoria.

I have continually been worried by the Messrs Ettershank ever since I first selected. Whether this may be a ruse on their part to cause me to lose my land altogether the land is even more preferable to us than the £5000 as it is taken up as a permanent home for my family. Moreover I may state that land is letting up here with right of purchase at £10 per acre and my father and I have 100 acres under crops and fallow and as I have nothing else to depend upon now it would be a matter of the most serious consequences if I should be deposed of the land after spending so much time and money in improving it to its present state of a working proposition.

William Doody, Bears Lagoon, Letter to the Minister of Lands, 28 October 1877, PROV, VPRS 625/P0, Land Selection Files, Unit 353, Item 24567.

William Doody was 22 years old when he wrote that letter. He, his father Joseph Doody, and neighbouring small farmers, or 'selectors', were locked in conflict with powerful pastoralist, or ‘squatter’, interests represented by John Ettershank. The letter was decisive in finally deciding the conflict in favour of the Doodys and some of their neighbouring selectors.

By then, Joseph Doody was dying of diseases contracted on the Victorian goldfields. His long and mainly upwardly mobile journey had commenced in the London Road district in Manchester,[1] and culminated, like many other miners, in the selection of land under the Land Act 1869 with his oldest son, William, at Bears Lagoon, north-west of Bendigo. The selections might have gone unremarked and followed familiar patterns of hard work, and success or failure depending on their skills, entrepreneurial abilities, or luck. However, this was not to be. The Doodys and a dozen or so other selectors had chosen blocks of land that John Ettershank regarded as his own. He had acquired these under earlier lands Acts through what would seem to be employees acting as dummies on his behalf.

This situation set off a long and bitter struggle that is recorded in great detail in the Department of Crown Lands & Survey (Lands Department) records now held by Public Record Office Victoria. These records illuminate at the ground level, the conflict between the great squatters and 'liberal' governments attempting to establish a pathway to land ownership for the small farmer and cultivator, and between the selectors and the squatters themselves. The Doodys and Ettershank represent the human face of the political turmoil arising from the strident campaign to ‘unlock the land’, and which I argue is intrinsic to the consolidation of Victoria’s robust democratic tradition.

Settler: Joseph Doody

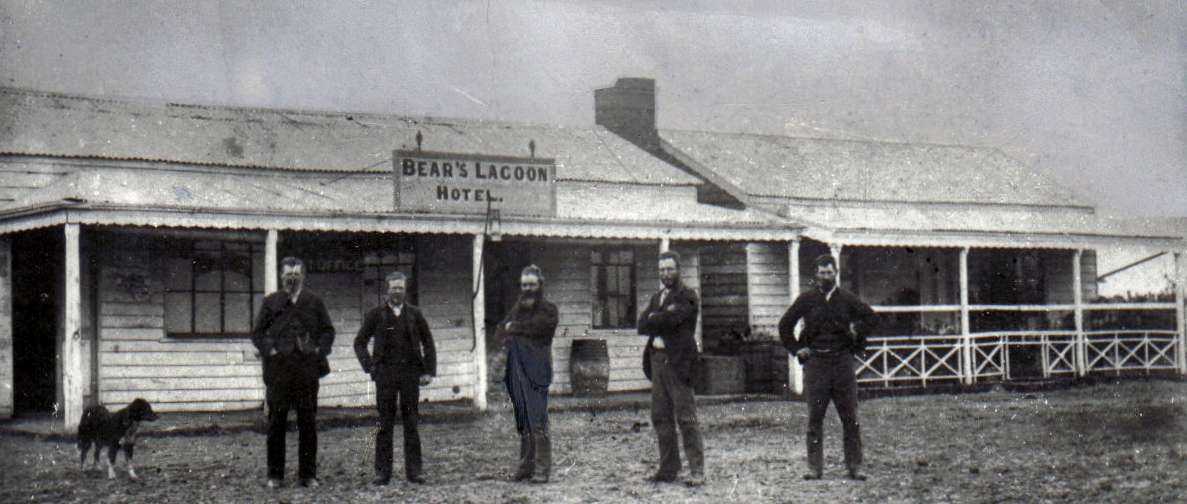

Joseph Doody had first selected land in the area of Bears Lagoon under the Land Act 1865. This Act was the Minister of Lands James Macpherson Grant’s first attempt to fix seriously flawed earlier land Acts and genuinely open up for selection Victoria’s rural lands to the small farmer. Doody was granted a lease over 71 acres (29 hectares) on Allotment 158B, Parish of Janiember, in the county of Bendigo on 17 December 1869. On 20 February 1873, he was granted freehold title for the land under Section 33 of Grant’s second and more effective land reform legislation, the Land Act 1869. This grant was dependent on certification that he had ‘made substantial and permanent improvements to the value of One Pound for every acre’ on the allotment.[2] On this land, Joseph Doody and his wife Fanny built the first Bears Lagoon Hotel and General Store, as well as meeting the cultivation requirements for freehold title.

After a successful career as a miner and investor, Joseph Doody had been declared bankrupt in April 1868 after he and fellow investors had overreached themselves on quartz mining ventures at Inglewood.[3] That he could select the land so soon after his bankruptcy is evidence of the vagaries of fortune for these gold diggers. He would have had to be discharged from bankruptcy to be able to select. This argues for at least one of those ventures paying off in a very short time. The average time it took selectors to make the required improvements and purchase the freehold title was eight to ten years. He did his in just three years.

In 1872, Joseph and his 18-year-old son William selected a further 560 acres (226 hectares) in four allotments to the south of Doody’s original selection. This land had originally been selected by Henry Henrickson under one of the earlier land Acts. In 1870, Henrickson travelled to New Zealand to join his brother permanently. He forfeited his selection, but requested that the four allotments be transferred to the Doodys in return for them compensating him for the improvements he had made and rents he had paid. The Lands Department gazetted the forfeiture then allowed the Doodys to re-select the blocks under Sections 19 and 20 of the Land Act 1869.[4] However, it is highly probable, though there is no direct evidence, that Henrickson selected the blocks as a dummy for John Ettershank. Certainly Ettershank considered the land to be rightfully his, as correspondence in the Doodys’ selection files and another file, titled ‘Correspondence regarding selections of Mr John Ettershank, Sandhurst Land District’, demonstrate.[5] His fight to reclaim that land and many other adjoining allotments in the Serpentine Creek/Bears Lagoon area, and the Doodys and other selectors fight to retain their title, resulted in what I call ‘The Battle for Bears Lagoon’.

Squatter: John Ettershank

John Ettershank, though a relative latecomer to the pastoralists ranks, came to represent in the public mind and in the view of 'liberal' governments, all that was bad about squatters. The Age newspaper described Ettershank and his brother as ‘land-grasping gentry’ who resorted to ‘dubious means’ to satisfy their ‘appetites’.[6] His name also crops up in parliamentary records in connection with alleged bribery and improper appointments.[7]

Ironically, Ettershank’s migratory journey crosses with Joseph Doody’s at several points before they both finally arrived at Bears Lagoon and came into conflict. John Ettershank was of middle class Scottish origin, and a qualified civil engineer. He moved to Manchester soon after qualifying where he was involved in the construction of new engineering works and warehouses—some of which Joseph may have worked on as a plumber and glazier. But he did not stay in Manchester for very long. Migrating to Victoria with his new wife, Christina, older brother Edward, and Christina’s brother, William Eaglestone, they arrived in Melbourne in December 1852 as unassisted migrants.[8] Obituaries and historian Ian Itter claim that they came out to work on the construction of the Alfred Graving Dock at Williamstown, but construction of the dock did not start until 1864 and in that year a branch of the engineering firm that the Ettershank brothers established was awarded one of several contracts put out to tender.[9]

It is probable that the whole family group would have migrated to participate in the gold rush and travelled to Ballarat soon after arriving in Victoria. Whether they actually dug or mined on these fields is impossible to ascertain. But the Ettershanks and Eaglestone saw their opportunity to put their engineering skills to work; importing parts and assembling or constructing engines, pumps, boilers and other engineering machinery increasingly required to extract gold.

Joseph Doody was engaged in similar enterprises in Bendigo, and their paths may well have crossed when the Ettershanks opened a branch of their engineering works in Bendigo towards the end of the 1850s. Ettershank quickly realised that greater profits could be made as a stock agent delivering sheep and cattle to the hungry miners. Though he did not pioneer the stock routes, which saw sheep and cattle driven from New South Wales and southern Queensland down the inland corridor, he turned it into a very lucrative business that broke the monopoly Sydney stock agents had previously held over the stock trade. It was this business which first bought Ettershank to Bears Lagoon.[10]

Bears Lagoon

Bears Lagoon is a narrow gash in the alluvial flood plains about 55 kms north-west of Bendigo, formed by a fracture along a fault line in the underlying rock. It is now silted up as the result of an irrigation channel running through it and is wadeable, but was once very deep, supporting abundant games and fish. It may have been fed by an artesian water supply as well as the network of creeks that drained into the Serpentine Creek and then the Loddon River. A local farmer says that it would never dry up even in the worst droughts. The area around it is flat and covered in natural grasslands. Conveniently located mid-way between the Murray River crossings and Bendigo and Ballarat, it was an ideal place to rest and fatten the cattle and sheep before driving them south down the Serpentine Creek.

The first Europeans to settle around the lagoon were the managers and shepherds of some of Victoria’s biggest squatters, including John Bear, after whom the lagoon was named. From 1862, attempts were made to break up the pastoral estates and open up the land in the Sandhurst (Bendigo) district for selection. John Ettershank seems to have used flaws in the early land Acts to place a number of employees on blocks throughout the East Janiember parish which is centered on Bears Lagoon. He would then assist them with finance for improvements and lease payments. The improvements were often minimal and the blocks used exclusively for pasturing sheep and cattle.

Consequences of the Land Act 1869

After the Land Act 1869 was passed, a substantial number of these early selections came under investigation from the Lands Department, and much of the early material in the correspondence regarding selections of Mr John Ettershank consists of affidavits, letters, and statements in relation to these investigations. It may have been the Doodys who stirred the Lands Department to look at those selections. At least one affidavit was obtained by Joseph Doody from a shepherd who used to work for Ettershank. Between 1872 and 1874 several of the pre-1869 selections were forfeited for non-payment of rent, non-compliance with the provisions of the Acts, and non-performance of covenants in the respective leases. In at least one case a widow, Margaret Horan, was allowed to re-select the allotment under sections 19 and 20 of the 1869 Act. On other allotments, new selectors quickly selected the forfeited selections.

Ettershank came out fighting claiming that, on all the selections concerned, he had right to title as all the original selectors had assigned title to him in return for being advanced sums of money.[11] That was the beginning of a long legal struggle that went all the way to the Privy Council where he won one case on appeal and lost another.[12] Further protracted negotiations between the Lands Department and Ettershank and his lawyers followed through until 1886 when they finally agreed on a settlement. In return for paying back rent and penalties of £1172.10.00, he was granted certificate of title on 1212 acres (490 hectares) selected in 1865. Among the people displaced was Margaret Horan who received £300 in compensation from the lands board. Ettershank did surrender his claim to several other titles where selectors had ownership and grant of title was already confirmed.[13] This presumably included the Doodys selections.

Whether people like Margaret Horan eventually lost their selections to Ettershank, while others like the Doodys would successfully fight off Ettershank, came down to how much influence they could bring to bear to counter the influence that Ettershank could wield to frustrate their claims. It could not have been an easy fight for them. At the very beginning of William Doody’s selection file is a letter from Ettershank addressed to the Assistant Commissioner of Land that reads: ‘Sir, I have the honour to send you on the leaf the different allotments of land which the President agreed he would not present to be selected pending the adjudication and settlement of my claim to them’. A pencilled note on the letter says 'not to be selected pending settlement of Mr Ettershank’s claim’. This indicates that Ettershank could clearly wield influence at the highest levels of the public service. Yet, subsequent to that note, the Sandhurst Lands Office did proceed with the applications for selection by Joseph and William Doody, suggesting that there might have been considerable division within the Lands Department.[14]

Joseph and William were prolific and literate correspondents who demonstrated considerable understanding of their entitlements and rights. Despite starting work sometime around the age of nine or ten in a dyeing works in Manchester, Joseph seems to have acquired a good elementary education and absorbed much of the radical political and chartist thought prevalent during his childhood and teenage years.[15] His son, William, was born on the goldfields and grew up there. His letters are well-written in a neat and legible handwriting (see below) that suggest educational opportunities on the goldfields were far from inadequate.

Political and land reform

The settler's struggle for their selections coincides with a time of considerable political upheaval in Victoria as the liberal groups of the lower house battled to assert their dominance over the upper house to implement their reform programs, particularly land and electoral reforms. Joseph Doody seemed to have ready access to Grant, who served as Minister of Justice in the Berry government between 1875 and 1880, and Francis Longmore who was Minister of Lands in that period and, like Berry and Grant, committed to breaking up the great pastoral estates through a punitive land tax. There are also letters in their selection files from various members of the Legislative Assembly querying the department as to why the Doodys were having such difficulty in gaining final freehold title to their selection, when they had made their improvements and paid the money due on their leases.

In late 1876, Minister Longmore directed that title be granted expeditiously to both the Doodys. Though grant of title was dated to Joseph and William Doody respectively on 22 July 1876 and 10 February 1877, they did not receive the certificates of title for another two years as the Sandhurst office, so supportive in the early years, seems to have fallen under the influence of Ettershank and found one excuse after another to not issue the certificates. The last excuse was based on their receipt of an anonymous letter reporting that Joseph Doody was running a business on his selection—the Bears Lagoon Hotel, Post Office and Blacksmith shop. Though the letter of the law said this could be cause for forfeiture of selection, the Lands Department on the whole tended to ignore the establishment of such businesses as they were vital to the development of viable rural communities. An exasperated and terse order from the commissioner finally resulted in issuing of the certificates. The Doodys were then officially able to join their fellow selectors in developing what was initially a thriving community similar to many springing up across Victoria.[16]

Conclusion

In coming to Australia, Joseph Doody was seeking independence and a route to property ownership denied to him and his peers in the United Kingdom. Gold and agricultural land represented the possibility of achieving this. The gold fields and the land also became the battleground on which a new social democratic society emerged. The struggle to unlock the land, which the Doodys' personal struggle personifies, created a new and substantial property-owning small business class with a substantial investment in both a social democratic policy and the country as a whole. The journey to Victoria had exposed Joseph Doody to new political and social cultures which led him to participate in struggles against an oligarchy determined to preserve their entrenched privileges. His sons and grandchildren also played influential roles in their community by establishing a school, mechanics institute, an agricultural cooperative and other institutions.

Remarkably, the Bears Lagoon and Serpentine oligarch, John Ettershank, also contributed to making Bears Lagoon into a viable economic, social and cultural community. Not only did he provide substantial sums to develop its local institutions, in the late 1880s he also began sub-dividing his pastoral estate and selling it to local farmers, including William Doody, at generous prices and interest rates which allowed them to further develop viable and sustainable economic landholdings.

In 1916, three young men from the third generation of Doodys met up in Manchester to explore their grandparents' homeland prior to joining the Australian Army Corp on the Western Front. The Britain they were going to fight for would have been a very different one to that which their English contemporaries were being shipped off to fight for.

Endnotes

[1] Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, GB127.M9/40 Manchester Township (later City), Manchester Valuation Lists And Rate Books 1706–1900, 1841, p. 341/1833.

[2] PROV, VPRS 629/P0 Land Selection Files, Unit 30, Item 5389.

[3] Bendigo Advertiser, 18 April 1868, p. 2.

[4] PROV, VPRS 625/P0, Unit 200, Items 112423 and 12424; PROV, VPRS 625/P0, Unit 353, Item 24567.

[5] PROV, VPRS 1016/P0 Miscellaneous Correspondence Files, Unit 2, Correspondence regarding selections of Mr John Ettershank, Sandhurst Land District.

[6] 'How to check land monopoly', Age (Melbourne), 4 October 1873, p. 4.

[7] Argus, Melbourne, 4 October 1873, p. 4.

[8] PROV, VPRS 7666/P0 Inward Overseas Passenger Lists (British Ports), microfiche 022, p. 2.

[9] Heritage Council of Victoria, Victoria Heritage Database, ‘Alfred Graving Dock’, Place ID 1231, available at <http://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/1231/download-report>, accessed 20 February 2017.

[10] Ian Itter, John Ettershank—the red brick woolshed, Ian Itter, Swan Hill, Victoria, 2013, pp. 20–28. 'Ettershank, John (1832–1912)', Obituaries Australia, Australian National University, available at <http://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/ettershank-john-355/text356>, accessed 10 February 2016.

[11] PROV, VPRS 1016/P0, Unit 2.

[12] Edmund F Moore, The law reports 1875, Reprint, Forgotten Books, London, 2013, pp. 360–365.

[13] PROV, VPRS 1016/P0, Unit 2.

[14] PROV, VPRS 625/P0, Unit 12424.

[15] The National Archives of the UK, PRO: 1841, HO107/571/1/8/9.

[16] PROV, VPRS 625/P0, Unit 200, Items 12423 and 12424; PROV, VPRS 625/P0, Unit 353, Item 24567.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples