Last updated:

‘Mary (Molly) Winifred Dean (1905–1930): the murder, inquest and abandoned trial’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 15, 2016-2017. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Eric J Frazer

Mary (Molly) Winifred Dean was brutally murdered on 21 November 1930 in the inner-city suburb of Elwood, Melbourne. During the inquest that followed, attention focussed on Molly’s personal life, her torrid relationship with her mother, Mrs Ethel Dean, a widow, and Adam Graham’s possibly improper relationship with Mrs Ethel Dean. Although witnesses to Molly’s journey home the night she was murdered came forward, none actually saw her being attacked. Adam Graham was committed to trial for the murder by the Coroner, however, the Crown Prosecutor did not proceed with the case, presumably due to inadequate evidence.

Insights are sought into Molly’s professional and private life and the circumstances surrounding her death. Aspects of the police investigation and the subsequent inquest are discussed and drawn together to flesh out a rather tragic story. The article draws on the available archival records held by Public Record Office Victoria, essentially the teacher record books and the brief to assist the Coroner. These are supplemented by the extensive newspaper accounts of the time and two well-known books published years later. Unfortunately, the murder remains unsolved!

Mary (Molly) Winifred Dean was brutally murdered in the early hours of 21 November 1930 in the inner-city suburb of Elwood, Melbourne. A sensational two-day inquest followed on 29–30 January 1931, much of which centred on Molly’s personal life and her torrid relationship with her mother, Mrs Ethel Dean, a widow. Adam Graham’s long-term friendship with the Dean family and, in particular, his possibly improper relationship with Mrs Ethel Dean were also featured. Although there were a number of witnesses to Molly’s journey home from the theatre that fateful night, no eye witnesses to her attack were forthcoming. In the end, Adam Graham was committed to trial for the murder by the coroner.

Finding a murder

The author came across the story of Molly Dean’s murder while researching the history of his home in Elwood leading up to its centenary in late 2014. The Port Phillip Bay-end of Milton Street only began to be developed around 1910 following the filling of a large area of swamp land. Molly lived in the same block as the author—only a few doors away. She was brutally attacked in an adjoining street. The newspaper reports of her murder and inquest were detailed and frequent, making them impossible to ignore during suburb/decade keyword searches via Trove. The stories were published widely in both the local and interstate newspapers of the day. Plainly, public interest was high, perhaps driven by possibly related murders of other young women in Melbourne in the months preceding Molly’s death.

This article delves into Molly’s professional and private life, the circumstances surrounding her death, the police investigation and the subsequent inquest, including Mary’s acquaintances, potential suspects, and the accused, Adam Graham. It draws on the available archival records held by Public Record Office Victoria, essentially the Teacher record books (VPRS 13579) and the brief to assist the coroner (VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs). These are supplemented by the extensive newspaper accounts and some literary sources published years later. The story is fascinating, but the mystery surrounding a murder, so close to 'home', remains!

Living on through fiction and fact

It seems surprising to find an unsolved murder, committed decades earlier, featuring in two well-known books: My brother Jack by George Johnston[1] and The eye of the beholder by Betty Roland.[2] In Johnston’s novel, Mary Dean and Colin Colahan (whom Molly was involved with at the time) are portrayed by the characters Jessica Wray and Sam Burlington (the author, George Johnston, apparently knew Colahan in postwar-London).[3] Necessarily, the general story is dramatised to suit the author’s purpose and the focus is on his character Burlington's reactions to the murder. On the other hand, Betty Roland was Molly's friend and she provides detailed insights about Molly's relationship with Colin Colahan, although these are sometimes second-hand accounts of happenings some 50 years previously. Roland felt that she had somehow contributed to Molly’s death having sent her the theatre tickets for that night. Regardless, Molly is one storyline in her book, the account occupying only a very small part of the text.

The story lives on, in even more dramatic fashion, in the play Solitude in Blue, written and directed by Melita Rowston. It was presented in 2002 at Stables Theatre, Sydney (Griffin Theatre Company); the storyline begins:

Melbourne 1930. A murderer is lurking the streets. The strangled bodies of young girls are piling up in the laneways of suburbia, casting a shadow over the sun-bleached days of summer. In the heat of the city, Molly Dean barges into painter Colin Colahan’s life and seduces him with her words. She is determined to leave behind her dingy suburban roots and become a ‘bohemian’ writer. Colin is enchanted by this fiery creature who drags him away from his elite artistic circle and forces him to paint with his heart instead of his head.[4]

Apart from the creative use of the case for fiction, there is also a realistic portrayal of the case in two brief articles written by TM Sellers, an historian with a particular interest in Brighton General Cemetery where Molly Dean was buried.[5] His two accounts are similar and neatly summarise the story, principally reflecting the newspaper reports of the time. In addition, Sellers provided images of the crime scene as it is today. Finally, Molly’s story was mentioned in the City of Port Phillip: Elwood Heritage Review published in 2005;[6] this account relies on both Sellers’ summary and Roland’s personal memoir. The main players are shown in Figure 1, as pictured in Sydney’s Truth on 1 February 1931.

Professional and personal insights

The most valuable entrée into Molly’s professional life, right up until the time of her death, is to be found in the Teacher Record Books maintained by the Victorian Education Department (VPRS 13579;[7] see Figure 2). Molly entered Teachers’ College on 10 February 1926, following four years as a junior trainee at the St Kilda (Brighton Road) school. As a trainee, in mid-1925, she was described as 'intelligent & bright & capable of doing v[ery] g[ood] work'. At college, she was described as 'original & of strong personality' and 'an exceptional student'. She left College on 31 December 1926 with a Trained Primary Teachers Certificate having been awarded the '1st Geadman Prize (equal) for teaching (Primary)'. She was appointed as an assistant teacher on 1 January 1927 at the Faraday Street Carlton School. By September 1928, her teacher grading had increased from 'E' to 'C'—'she exercises a pleasing influence over the members of her grade'.

Molly was appointed a temporary assistant at the Queensberry Street North Melbourne School (an 'Opportunity' school for children with learning difficulties) on 16 March 1929 and was working there at the time of her death. Here she maintained a C+ grading, and the comments on preparation, teaching, and organising were always very positive. Her last assessment was documented on 13 November 1930, only about two weeks before her untimely death: 'Is doing work which on the whole varies between a good & a v[ery] g[ood] standard, but is not always punctual'. Surprisingly, punctuality had never previously been mentioned as an issue over the almost nine years that the record covers (February 1922 – November 1930).

A pre-inquest statement[8] reveals that Molly had been in contact with the Vice-Principal of the Teachers College Carlton, George S Browne. At the beginning of November 1930, Molly 'asked advice about lodging an application for three months leave of absence in order to try her hand at journalistic work'. About ten days before her death, he visited her school and saw her headmaster, who informed him that 'her work of late was very unsatisfactory and that he might have to report her to the Department'. It seems that Molly’s desire to change career direction was beginning to affect her teaching performance. In fact, Molly had already had a long blank-verse poem, entitled 'Merlin', published in Verse, a Melbourne publication, in November 1929.[9] She had also been elected a member of the Society of Australian Authors at the beginning of 1930.[10]

Betty Roland’s book gives valuable glimpses into Molly’s private life, particularly her involvement with the Meldrumites (followers of the school of painting founded by Duncan Max Meldrum in Melbourne) during the 1920s. Molly was intimately involved with Colin Colahan, an artist, who was the initial suspect in her murder. Although published some 50 years after Molly’s death, Roland’s account seems remarkably fresh, obviously written with the eye of a keen observer:

... Molly held my interest. She was ruthless and, I felt, might be dangerous, but she was never dull. Lena [Skipper] told me that it was she who had induced Colin to divorce his wife, though she might not have succeeded had the marriage been a happy one.[11]

Roland also confirmed the severely strained relationship between Molly and her mother:

Her homelife was deplorable as her widowed mother resented the fact that Molly insisted on living away from home and took violent exception to her involvement with the ‘Bohemians’, in other words, the Meldrumites. But Molly ignored all this and spent most of her time in Colin’s studio, earning her living by teaching backward children at a special school.[12]

The murder

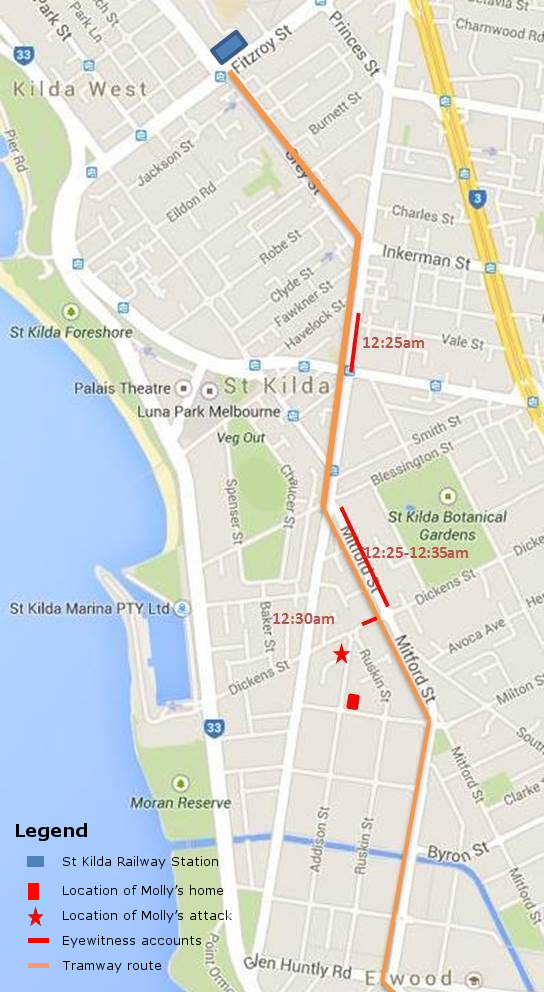

Apparently, Molly had arrived at St Kilda Railway Station very late on the evening of 20 November 1930, having attended the theatre with friends, including Colin Colahan. In fact, she had stayed at Colahan’s Hawthorn flat on the previous night.[13] She was too late for the last tram which would have dropped her only a few blocks from her home. Therefore, Molly was forced to walk the 2 km, apparently following the tram route up Grey Street, then down Barkly and along Mitford Streets. A number of sightings of Molly were reported in written statements given soon after her death and in evidence at the inquest. One of these, by Edward Roy Cole, reported seeing Molly on Barkly Street near Havelock Street[14] and the corner of Carlisle Street.[15] Another onlooker, Sydney Arthur Gordon,[16] saw 'a young lady walking briskly along Mitford Street' between Blessington and Dickens Streets at about 12:25–12:35 am, and James Hugh Nankivel[17] saw Molly walking west on Dickens Street towards Addison Street.

The Brighton Electric Tramway ran from St Kilda Railway Station via Grey Street, Barkly Street, Mitford Street, Broadway, Ormond Road, St Kilda Street and Esplanade to Park Street, Middle Brighton.[18] There was a tram stop on the corner of Dickens and Mitford Streets.[19] Thus, Molly was taking a familiar and direct route home (see map Figure 3). As an aside, one might wonder why there were so many witnesses to events in the very early morning hours. The weather records suggest that the overnight temperature would have been relatively mild, with a maximum on Thursday 20 November of 80°F (26.7°C) and a minimum of only 60°F (15.6°C) on Friday 21 November[20]—hardly a heat wave.

Molly was discovered, severely injured, at about 1 am on Friday 21 November 1930 in a laneway just opposite 5 Addison Street, Elwood, less than 200 metres from her home at 86 Milton Street. The residents (Frederick Owen and his sister, Beatrice) heard moaning and discovered the girl’s belongings and blood on the footpath outside their gate.[21] Frederick called the police and Constable Guider attended the scene at about 1:30 am, soon discovering Molly in the laneway opposite.[22] Molly was taken by ambulance to the Prince Alfred Hospital arriving in the ward at about 2:10 am.[23] Soon after, Mrs Ethel Dean and her son, Ralph, were informed of the situation and transported to the hospital by the police. Molly died of her injuries about two hours later.

The earliest newspaper report of Molly Dean’s murder was published in the Argus on 22 November, only one day after the event.[24] Surprisingly, this was extremely detailed (1,433 words) covering Molly’s teaching and literary leanings, her movements on the evening of her death, a grim description of her injuries, and details of the initial police investigation. It seems that those in charge of the case, senior detectives O’Keeffe and Lambell, released information in an effort to encourage witnesses to come forward; they had already interviewed residents of Addison and Dickens streets.

On Monday 24 November, it was confirmed that the investigation was being conducted on the assumption that the crime had been committed for motives of jealousy, and detectives issued an appeal to the public to assist them to clear up the mystery.[25] This was followed by a series of newspaper articles over the period 25–29 November 1930[26] but, despite the intense publicity, no arrests were made.

The inquest

The brief to assist the coroner[27] reveals that the police enquiry had been exhaustive, with 38 potential witnesses interviewed (see Figure 4). Just before the inquest, it was reported that: 'In police circles it is believed that at least one person will be committed for trial on a charge of murder'.[28] The inquest eventually began on 29 January 1931, with intense publicity over the two days of proceedings.

Adam Graham was clearly a person of interest to the police. Indeed, the statements by Harry Coles[29] and James Nankivell[30] suggest that their identification of Adam Graham in the area that night might have been 'encouraged' by police. However, the most sensational evidence revolved around Mrs Ethel Dean’s relationship with Adam Graham. Mrs Dean claimed intimacy, Adam Graham denied it. In the event, the coroner, Mr D Grant, finally committed Adam Graham to trial for murder. It seems that he was swayed by a number of factors including Graham’s long-term relationship with Mrs Dean, their treatment of Molly, and some circumstantial evidence.

The Deans had been living in Milton Street since 1916 after the father (George Edward Dean) had died. The Graham family was related to Mrs Dean’s sister, Mrs Blyth, and they had lived with the Deans for 18 months when they came to Australia from Scotland in 1921. Adam continued to be a regular visitor to the Dean family home, often leaving his car under the street light outside their house for safe keeping. As early as 1928, Graham and Mrs Dean used to follow Molly by car to check on her acquaintances—in one case to Melbourne University where Molly met George Sell.[31]

Sarah Field, a schoolteacher and friend living at South Yarra, said Molly had told her that 'Mrs Dean wanted Molly to go with him [Graham] but she did not want to, because she did not like him'.[32] Molly’s brother, Ralph Dean, said that Graham had not paid attention to Molly for 4 or 5 years.[33] Indeed, no evidence of any close relationship was ever revealed during the inquest.

There was some circumstantial evidence: (i) blood stains were found on one of Graham’s suits; (ii) a man was seen at St Kilda Station with a peculiar gait—apparently like Graham’s; (iii) Graham was out on the night of the murder, returning at about 10:45 pm to his house in Gordon Street, Elwood, close to both Molly’s house in Milton Street and the scene of the murder in Addison Street; and (iv) there was disagreement between Graham’s mother and sister about exactly where he had slept that night (front bedroom or sleepout).

Finally and rather strangely, Mrs Dean was identified by her neighbours as having been seen in Milton Street at about 11:30 pm on the night of the murder. However, Mrs Dean claimed that she had been walking her dog much earlier, at about 8:00–8:30 pm.

Suspects and acquaintances

About two weeks before Molly’s murder, a 12-year-old schoolgirl was abducted from South Yarra and later found in the suburb of Ormond, strangled to death. However, the police believed that the motives in this crime and Molly’s murder were different.[34] Only two months later, on 10 January 1931, a 16-year-old girl, Hazel Wilson, was abducted and strangled, also at Ormond.[35] In the event, the police were correct. Arnold Karl Sodeman was executed at Pentridge Prison in 1936, having confessed to four murders of girls aged between 6 and 16 over the period 1930–1935, including the two above.[36]

Colin Colahan had met Molly about 12 months before her murder. They had become 'very friendly' and were frequently in each other’s company.[37] Colin was eliminated as a suspect very early in the police investigations because of two phone calls made by Molly (from St Kilda Station) to Colahan’s Hawthorn flat just after midnight on 21 November 1930. These firmly established his alibi. Colin was shaken by Molly’s murder, and further distressed by the inquest and publicity that followed. He departed for England in 1935 where be built a reputation as a portrait painter. In 1942, he was appointed an official war artist by the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. He died in Ventimiglia, Italy, in 1987.[38]

During the murder investigation, only a few other men were identified as having had a close relationship with Molly. In interviews with Detective Lambell, Mrs Dean mentioned Fritz Hart (Director of the University Conservatorium of Music),[39] Percy Leason (an artist)[40] and Mervyn Skipper (the Melbourne representative of the Sydney Bulletin) as having known Molly.[41] Mrs Dean certainly did not approve of Molly’s relationship with Mr Fritz Hart.[42] Sarah Field, a friend of Molly’s since 1926, revealed that she and Molly had been to Fritz Hart’s place[43] and she knew that Hart, who was a married man, had corresponded with Molly.[44]

Betty Roland, quoting from Lena Skipper’s (Mervyn Skipper’s wife) diary, sheds a little more light on Molly’s approach to relationships:

She is very clever and interesting to listen to as she expresses herself well and weighs all she says, but devotes most of her attention to the men. During Colin’s [Colahan] exhibition she showered more attention on Mervyn [Skipper] and Percy [Leason] than anybody else and eventually made Mervyn her 'platonic friend'. ...

Is she to go from one flirtation to another? I know one or two men she has offered herself to and they did not accept. She is not a femme fatale, she just likes to cause sensations. She says her virtue would never get in the way of her ambitions.[45]

George Edward (Teddy) Sell, a law student living at Ormond College, Melbourne University, was interviewed soon after Molly’s death. He had met Molly in late 1927 and took her out occasionally until the middle of 1928 when he was warned off by Mrs Dean.[46] Mrs Dean also admitted causing a scene when a young man named 'Clifford' bought Molly home;[47] unfortunately, no further details emerged. Finally, the 30 November 1930 issue of Truth[48] reported that Molly was frequently in the company of a man who paid her a great deal of attention while Colahan was touring for a couple of months ‘in search of subjects which might be committed to canvas'. However, this particular man was never identified, nor were any of the above-named implicated during the inquest.

The 'trial' and thereafter

The Crown Prosecutor did not proceed with the case, presumably due to inadequate evidence. The sequence of events leading to the abandonment of the prosecution against Adam Graham was well summarised by an article in the Argus of 6 March 1931:

Mr. Slater [State Attorney-General] said yesterday that the depositions containing the evidence of the 38 witnesses who gave evidence at the inquest had been submitted to Mr. Book (Crown Prosecutor), who had prepared an opinion in which he had advised that no presentment be filed against Graham. This opinion had been submitted to the other Crown prosecutors (Mr. Sproule and Mr. Nolan), who had concurred. Mr. Slater said that he had approved of the recommendation, and was acting accordingly.[49]

Most surprisingly, Roland reported that Adam Graham and Mrs Ethel Dean were married shortly after the inquest. Since 'a wife cannot be compelled to give evidence against her husband in a capital case, the Crown was deprived of its chief witness and the case collapsed'.[50] This explanation is plausible enough, but no evidence of such a union in the Victorian marriage records, or even co-habitation in the electoral records, could be found!

Clearly, Adam Graham had been affected by the whole experience. Following the decision by the Crown Prosecutor, Graham alleged that the detectives investigating the murder had used 'third degree methods'[51] in an attempt to extract a confession:

Graham said that the detectives interviewed him five times, and as a result of their brow-beating tactics he was a nervous wreck.

He added that the case cost him £350 in legal expenses and loss of work.

'Apparently a man has no redress for this sort of thing. I don’t know yet how much harm it has done to my health. The whole thing has nearly killed my mother,' said Graham bitterly [his mother, Isabella, died on 30 May 1946].[52]

Nothing seems to have come of the above complaint. Indeed, not that much is known about his life before or after the murder.

Graham was born in Cowdenbeath, Fifeshire, Scotland in about 1900, coming to Melbourne in 1921 and living with the Deans for about 18 months. From 1924 to at least 1942, he was a machinist (motor mechanic) living with his mother, brother and sister at 13 Gordon Avenue, Elwood. During the inquest, it was reported that he used to assist Ralph Dean with his work as a motor mechanic and do maintenance on Gladys Healey’s car. Gladys had known Graham for about 15 months (by sight for 7–8 years) and he visited her twice a week during the evening and on Sunday mornings.[53] Interestingly, Gladys’s car was garaged in the same Addison Street lane where Molly was found close to death![54] Eventually, in about 1947, he married Gladys (Marie) Healey and they lived at her family home, 98 Milton Street, just a few doors away from the (former) Dean household at 86 Milton Street. Adam Graham died at his home on 3 September 1980 and was cremated at Springvale Crematorium. Gladys pre-deceased him by only about two years (in 1978). Mrs Ethel Dean had died almost 20 years previously, on 12 October 1962.

As late as 1966, tantalising reports regarding Molly Dean’s murder appeared in the press.[55] Someone in Brisbane had sent the Chief Commissioner of Police, Victoria a letter offering information. It said: 'Would your department still be interested in some information that will lead to an arrest regarding the Molly Dean case?' Perhaps this communication was somehow stimulated by the 1964 publication of George Johnston’s My brother Jack which featured the ‘Jessica Wray’ murder.

The message implied that the murderer was known to the 'informant' and was still alive. Assuming that the perpetrator was the same age as Molly in 1930 (that is, 25 years old), he/she would have been about 60 in 1966. Ex-detective Percy William Lambell, then 76 years old, was interviewed at the time the letter was received. He was still living in Elwood and hoping 'to have it cleared up at least'.[56] Despite the efforts of Detective-Inspector Frank Holland, chief of the Homicide Squad, no further information was forthcoming so, by now, some 85 years after the murder, the secret has surely gone to the grave!

Concluding remarks

So, what are we left with? The life of a young woman, possibly on the threshold of a promising literary career, cut short without explanation. Molly was brutally bashed, dragged into a laneway and further assaulted but, given the forensic evidence, this was not necessarily sexual in nature. One could speculate that it was a random attack, but the 'information' received by police in 1966, some 36 years later, makes that seem unlikely. At the time, the police investigation was exhaustive. They assumed a motive of jealousy and pursued the Dean family friend, Adam Graham, whom Molly apparently abhorred. However, they failed to unearth sufficient hard evidence for the prosecution to proceed. Graham’s close relationship with Molly’s mother, Mrs Ethel Dean, and her antagonism towards any of Molly’s male acquaintances were complicating factors. If Mrs Dean had not enlisted Graham’s help by following Molly in his car on several occasions, this connection would have appeared less significant. The press of the day sensationalised any negative aspects of the evidence given at the inquest and one wonders what influence this would have had on a subsequent trial.

Molly was very young and apparently a successful teacher at a special State School in North Melbourne. However, she wished to pursue a literary career and her application to teaching began to suffer as she sought opportunities to pursue her dream. She tended to associate with the 'Bohemian' set, as exemplified by the promising painter, Colin Colahan, and other glitterati. She was rebellious, clashing repeatedly with her mother over such relationships and leaving home on several occasions to live independently. Betty Roland’s autobiography provided insights into Molly’s circle of friends and her ambiguous approach to relationships, but gave no suggestion of potential suspects.

Although there is no resolution to Molly’s particular story, some universal themes endure. We have seen the sometimes inevitable discord between the generations, youth wanting independence and freedom from authority, and striving to find purpose and fulfillment in life. Fortunately, violent crime is not usually part of that story!

Endnotes

[1] George Johnston, My brother Jack, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2013.

[2] Betty Roland, The eye of the beholder, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1984.

[3] R Darby, S Pearce, K Gelder, J Hooton, D Anthony & R Haese, 'Reviews', Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 21, no. 52, 1997, pp. 164–174.

[4] Melita Rowston, Solitude in Blue, <http://www.melitarowston.com/#! solitude-in-blue/cdt4>, accessed 2 January 2016.

[5] TM Sellers, 'The artist, the fiance and murder at Elwood', St Kilda Chronicle, vol. 4, no. 2, December 2000, pp. 27–28; 'The artist, the fiancé & murder at Elwood', History of Brighton General Cemetery, available at <http://brightoncemetery.com/H istoricInterments/Crimes/dean.htm>, accessed 2 January 2016.

[6] Heritage Alliance, Elwood Heritage Review, Vol. 1: Thematic history citations for heritage precincts, prepared for City of Port Phillip, 2005, ch. 4.1, p. 34, available at <http://www.portphillip.vic.gov.au/default/CommunityGovernanceDocu ments/Volume_One_Thematic_History_and_Heritage_Precincts.pdf>, accessed 2 January 2016.

[7] PROV, VPRS 13579/P1 Teacher Record Books, Unit 75, Teacher Record Number 22525: Mary Winifred Dean.

[8] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 2383, Item 187, Inquiry concerning the death of Mary Dean: brief to assist the Coroner, 1931, p. 31.

[9] ‘Molly Dean’, Cairns Post (Qld), Saturday 24 January 1931, p. 11; M Dean, 'Merlin', Verse, vol. 1, no. 2, November–December 1929, Hawthorn, Vic., pp. 11–13.

[10] 'A talented writer', Cairns Post (Qld), Tuesday 25 November 1930, p. 5.

[11] Roland, The eye of the beholder, p. 64.

[12] Ibid., pp. 65–66.

[13] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 8.

[14] 'Death of Mary Dean, "mystery" witnesses, startling evidence likely', News (Adelaide), Saturday 24 January 1931, p. 1.

[15] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 13.

[16] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 16.

[17] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 17.

[18] Yarra Trams, 'The early days', available at <http://www.yarratrams.com.au/about-us/our-history/tramway-milestones/the-early-days/>, accessed 16 January 2016.

[19] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, pp. 27–28.

[20] 'Temperatures at capital cities', Age (Melbourne), Friday 21 November 1930, p. 12, Saturday 22 November 1930, p. 16.

[21] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, pp. 20–21.

[22] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, pp. 44–45.

[23] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 22.

[24] 'Elwood murder. School teacher’s death. Was jealousy the motive? Some unusual features', Argus (Melbourne), Saturday 22 November 1930, p. 2.

[25] 'Elwood murder. Tracing victim’s movements. Public asked to help. Was it a crime of jealousy?', Argus (Melbourne), Monday 24 November 1930, p. 9.

[26] 'Jealousy motive for bohemian girl’s murder, killing of Mary Dean was savagely, fiendishly brutal. Dead teacher was talented and pretty, led bohemian life; mingled with artists. Did slayer accompany her?', Truth (Sydney), Sunday 23 November 1930, p. 13; 'Elwood murder. What was the motive? Other attacks recalled. Tracing victim’s movements', Argus (Melbourne), Tuesday 25 November 1930, p. 7; 'Elwood murder. Women describe suspect. Police receive anonymous letter', Argus (Melbourne), Wednesday 26 November 1930, p. 7; 'Elwood murder. Description of suspect. New lines of inquiry', Argus (Melbourne), Thursday 27 November 1930, p. 8; 'Elwood murder. No new theories. Other attacks recalled', Argus (Melbourne), Friday 28 November 1930, p. 7; 'Search for murderers. Question of rewards. Not necessary, says General Blamey', Argus (Melbourne), Saturday 29 November 1930, p. 22.

[27] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187.

[28] 'Death of Mary Dean, “mystery” witnesses, startling evidence likely', News (Adelaide, SA), Saturday 24 January 1931, p. 1.

[29] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 11.

[30] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 17.

[31] 'Crying girl at 12.30 a.m., night of Elwood murder, St. Kilda scenes, man and two women on station, inquest stories', Evening News (Sydney), Thursday 29 January 1931, p. 7.

[32] Ibid.

[33] 'What fiend battered Molly Dean to death?', Daily News (Perth, WA), 29 January 1931, p. 1.

[34] 'Elwood murder. School teacher’s death. Was jealousy the motive? Some unusual features', Argus (Melbourne), Saturday 22 November 1930, p. 2.

[35] 'Ormond inquest. Features similar to Dean murder', Canberra Times, Friday 20 March 1931, p. 6.

[36] Find a grave, 'Arnold Karl Sodeman', available at <http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=87446962>, accessed 16 January 2016.

[37] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 8.

[38] G Kinnane, 'Colahan, Colin Cuthbert Orr (1897–1987)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/colahan-colin-cuthbert-orr-12333>, accessed 7 January 2016.

[39] T Radic, 'Hart, Fritz Bennicke (1874–1949)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hart-fritz-bennicke-6589>, accessed 11 November 2015.

[40] LJ Blake, 'Leason, Percy Alexander (1889–1959)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/leason-percy-alexander-7139>, accessed 11 November 2015.

[41] 'Mary Dean Inquest', Longreach Leader (Qld), Friday 6 February 1931, p. 19.

[42] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, pp. 26, 31–32.

[43] ibid., pp. 24–25.

[44] 'Crying girl at 12.30 a.m., night of Elwood murder, St. Kilda scenes, man and two women on station, inquest stories', Evening News (Sydney), Thursday 29 January 1931, p. 7.

[45] Roland, The eye of the beholder, p. 65.

[46] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, pp. 34–35.

[47] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 54.

[48] 'Elwood murder still a deep mystery. Killer of Mary Dean left no traces behind. Police want to see man she met often while her fiancee was away', Truth (Sydney, NSW), Sunday 30 November 1930, p. 14.

[49] 'Murder of Mary Dean, charge against Graham, no presentment, Attorney-General’s decision', Argus (Melbourne, Vic), Friday 6 March 1931, p. 7.

[50] Roland, The eye of the beholder, p. 73.

[51] '"Third Degree": Adam Graham’s charges, Mary Dean case', Cairns Post (Qld), Monday 9 March 1931, p. 5.

[52] ‘Deaths: Graham’, Argus (Melbourne), Saturday 1 June 1946, p. 23.

[53] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 2383, Item 187, p. 40.

[54] 'Crying girl at 12.30 a.m., night of Elwood murder, St. Kilda scenes, man and two women on station, inquest stories', Evening News (Sydney), Thursday 29 January 1931, p. 7.

[55] 'Police given lead on 1930 murder', Age (Melbourne), Monday 14 February 1966, p. 5; A Dearn, 'New lead to1930 killing', Herald (Melbourne), Saturday 12 February 1966, p. 1; 'Will police get fresh tip? Molly Dean case', Herald (Melbourne), Monday 14 February 1966, p. 7; J Craven, 'Murder still rankles … even 35 years later', Herald (Melbourne), Saturday 19 February 1966, p. 7.

[56] J Craven, 'Murder still rankles … even 35 years later', Herald (Melbourne), Saturday 19 February 1966, p. 7.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples