Last updated:

‘Dating Melbourne's cesspits: digging through the archives’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 16, 2018. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Barbara Minchinton & Sarah Hayes.

From the late 1980s to the early 2000s, a number of archaeological digs were conducted at what was known as ‘Little Lon’ in Melbourne’s central business district. Public Record Office Victoria holds extensive archival records that supported these archaeological investigations; however, records specifying the dates when cesspits were closed were not identified until late 2013. The discovery of these records opens the possibility of correlating artefacts recovered from Little Lon’s cesspits with the people who might have discarded them. For the archaeologists working on material from Little Lon and other nineteenth-century sites in Melbourne, the records are an extraordinary boon. This paper places the creation of these records within the context of Melbourne’s waste management history, considering in particular the construction and closure of its cesspits.

Today, flush toilets are taken for granted in Melbourne. Few people will remember nightmen trundling up the back lane to collect their household’s night soil each week. These days, only campers in out-of-the-way places encounter cesspits and nightpans, those foul-smelling precursors to sewerage pipes. However, for historical archaeologists, old cesspits can be goldmines of information. From 1835 (when Europeans invaded from across Bass Strait) until the 1870s, Melbourne relied entirely on what we might regard today as camp-style toileting and rubbish arrangements. When cesspits were no longer needed for their original purpose, they were often used for getting rid of excess household refuse. Rubbish discarded by householders of the nineteenth century can provide all kinds of information about the people who owned it and the lives they lived, but it is necessary to establish when the cesspit was closed to accurately date the contents.

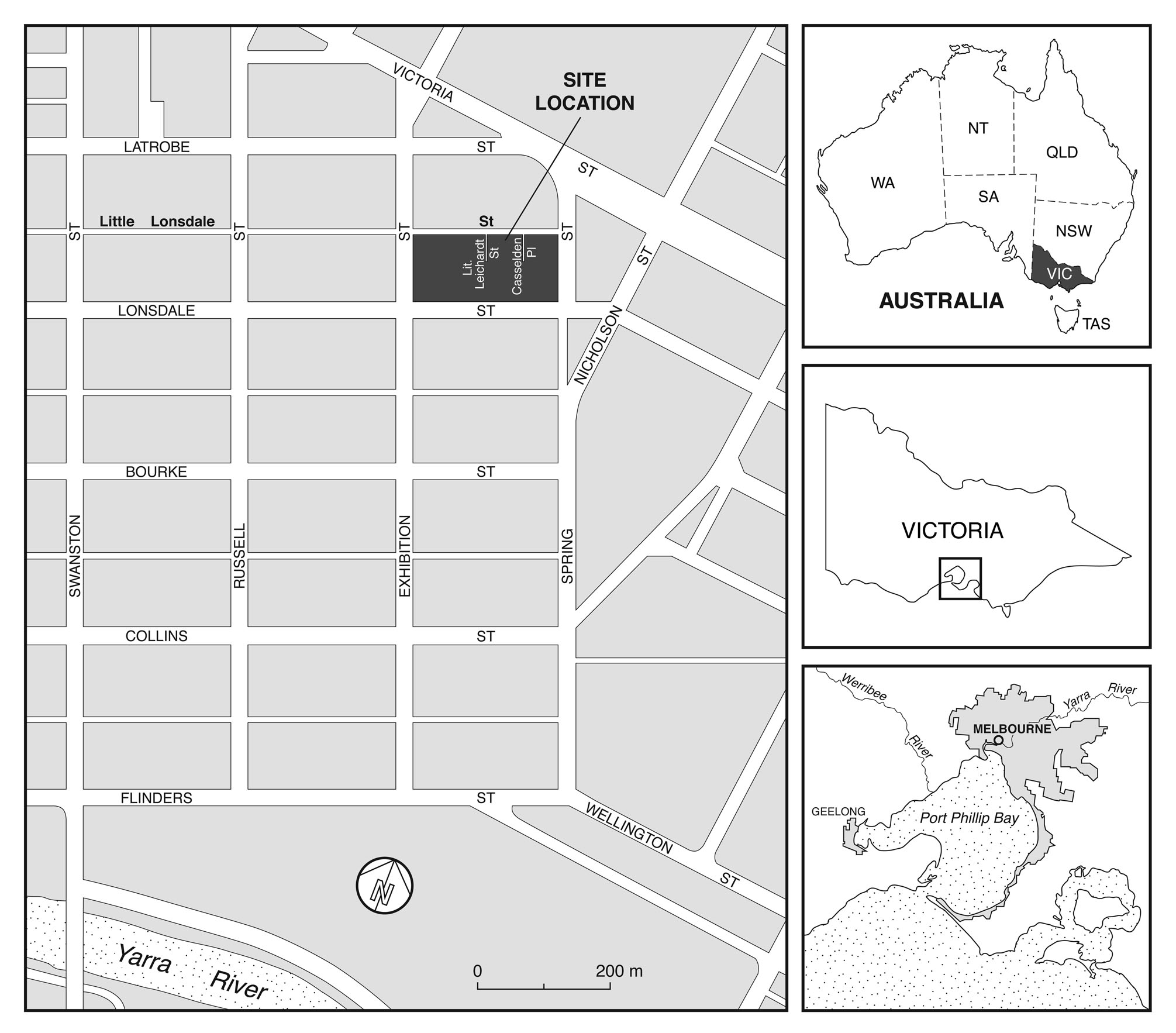

Since 1988, there have been numerous archaeological investigations conducted in the area of Melbourne known as ‘Little Lon’ (see Figure 1); however, historical archaeologists were often unable to date their finds with any degree of certainty because not enough was known about the process of cesspit closures in Melbourne. In 2013, by following the general history of Melbourne’s waste disposal and the ways in which the Melbourne City Council (MCC) administered and recorded it, research at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) revealed a series of records that provided specific dates for the closure of many of the cesspits in the Little Lon area. This article explains who created the records and for what purpose. Readers who are interested in urban archaeologists’ use of these records can also consult ‘Cesspit formation processes and waste management history in Melbourne: evidence from Little Lon’ in Australian Archaeology (2016).[1]

The research presented in this article forms part of an Australian Research Council funded project: A Historical Archaeology of the Commonwealth Block 1850–1950 (LP 0989224). The ‘Commonwealth Block’ refers to the block of land owned by the Commonwealth of Australia bounded by Little Lonsdale Street, Lonsdale Street, Exhibition Street and Spring Street in Melbourne’s north-east corner (Figure 1), commonly known as ‘Little Lon’. There were numerous archaeological research reports published about the area prior to the discovery of the MCC records.[2]

Figure 1: Location of Little Lon. Source: Ming Wei. Originally published in T Murray & A Mayne, ‘Imaginary landscapes: reading Melbourne’s “Little Lon”’, in A Mayne & T Murray (eds), The archaeology of urban landscapes: explorations in slumland, New Directions in Archaeology Series, University of Cambridge, 2001, p. 91.

Cesspit construction, the boards of health and the inspector of nuisances

Every city’s waste management history is different. For example, much of Sydney moved directly from cesspits to sewers.[3] By contrast, after cesspits were abandoned in Melbourne, nightsoil was collected from above-ground nightpans at the rear of each property for some time before sewerage pipes were installed. Consequently, answering the critical question of when a cesspit was closed in the Melbourne area requires an understanding of the broader waste management context. In the case of Little Lon, that context was controlled by the MCC.

The archaeological record shows that the construction of cesspits in Little Lon can be characterised in three stages.[4] The earliest pits were unlined—simple holes in the ground. Pits from the second stage were lined but still leaky. In the third stage, pits were sealed, having been lined with waterproof casks and/or puddled clay to prevent seepage. These stages can be clearly identified in the historical record, beginning with negative public comments about cesspits in newspapers in the 1850s.[5] In widely spread settlements, unlined pits allowed fluids to be gradually absorbed by the surrounding ground; however, in densely populated areas, there was too much fluid to be safely absorbed. By the late 1850s, seepage was a problem and responsible owners began lining their cesspits in an effort to reduce it. Conversely, when mains water became available from the Yan Yean Reservoir in 1857,[6] some owners began running water continuously into their cesspits (‘water-closets’), allowing the liquid overflow to run into the street channels through grates that held back solids. The increase in ‘offensive fluids’—as the MCC called them—caused the public to become even more concerned.[7] Yet, by 1860, very few cesspits in poorer neighbourhoods such as Little Lon had been lined.[8]

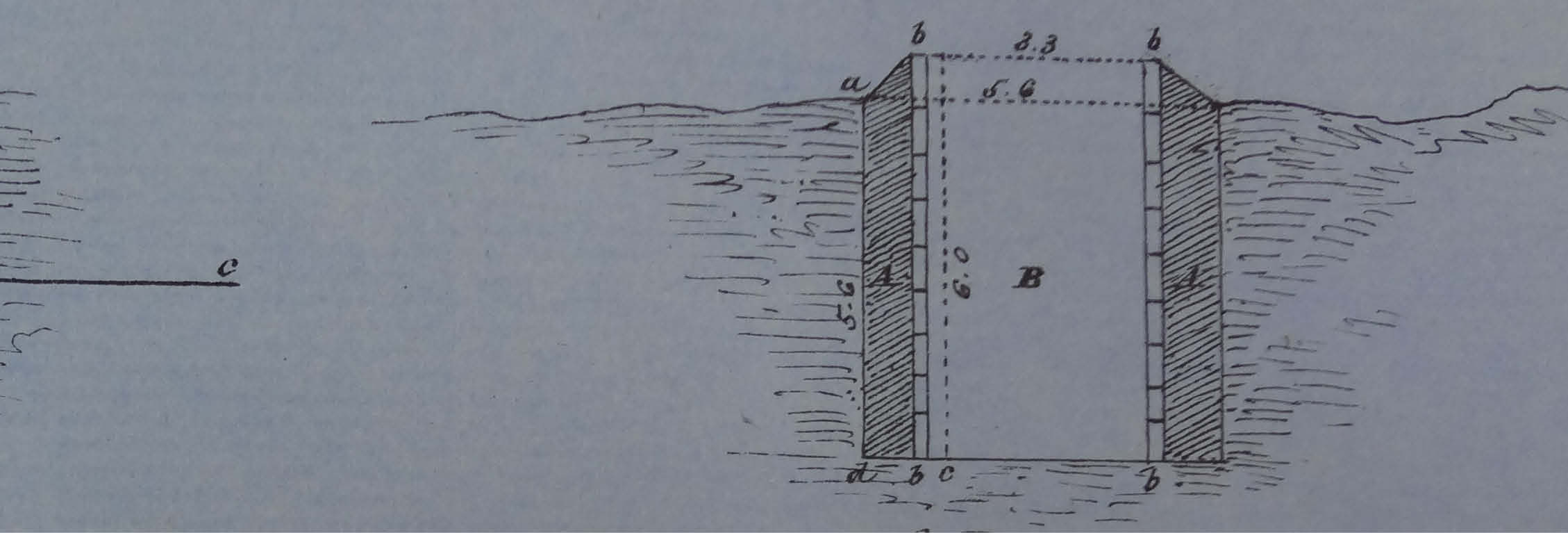

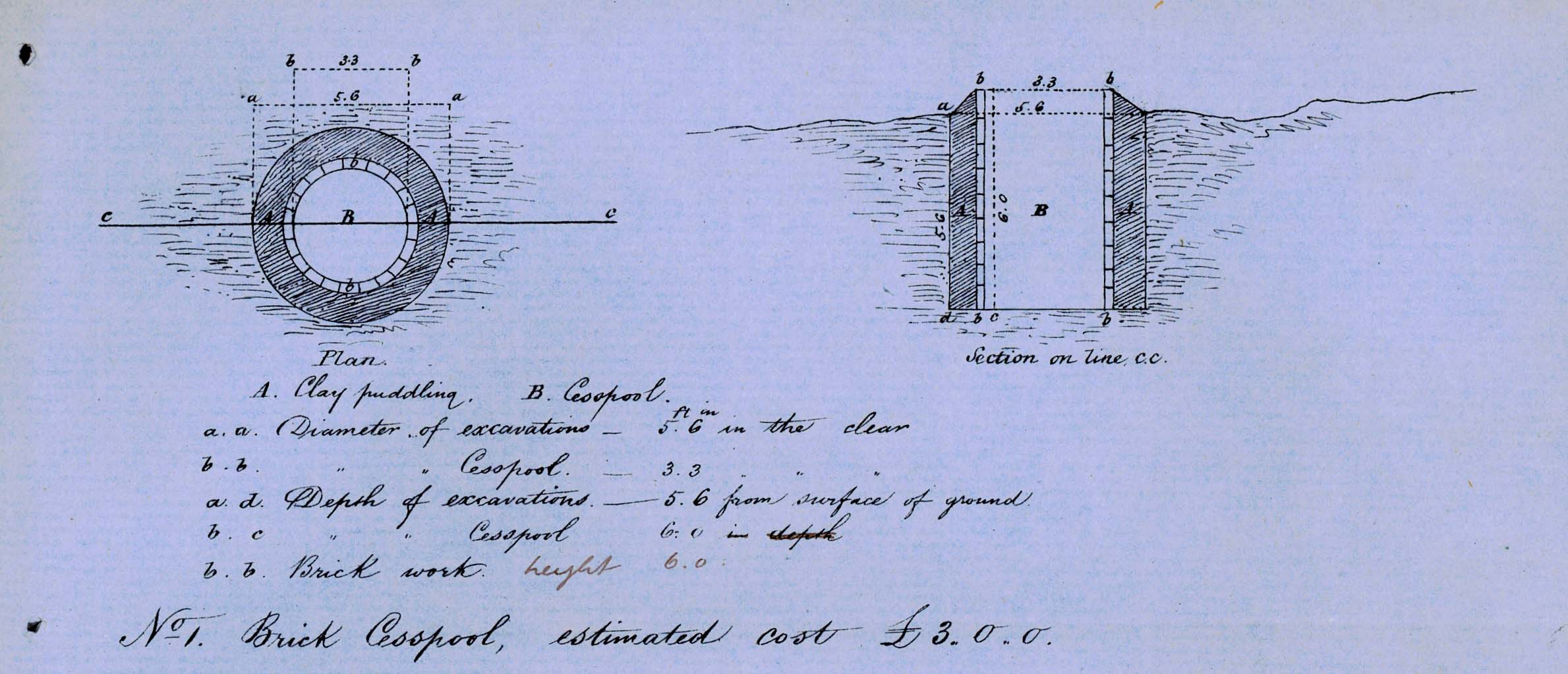

It was at this point that the MCC began to take responsibility for the public health aspects of Melbourne’s cesspits—hence, the story continues through the MCC archives. Administratively, the MCC was designated as a Local Board of Health (LBH)—an offshoot of the Central Board of Health (CBH) in the Chief Secretary’s Department—so that the MCC could enact its own by-laws relating to public health.[9] In October 1860, the MCC introduced by-law 42 for the annual licensing of nightmen; however, their work continued to be contracted and paid for by individual property owners. In 1864, there were only 10 nightmen licensed by the MCC for emptying ‘privy cesspits’ for a population of about 86,000 occupying about 9,300 buildings.[10] This indicates that most property owners still allowed their underground cesspits to overflow into the drains. The MCC could prosecute property owners for causing a nuisance under the Town and Country Police Act 1854, but privies had to be overflowing at the time of inspection to secure a conviction. No papers have been found in the archives relating to such prosecutions. In any case, preventing cesspits from overflowing did not solve the seepage problem. Seeking to address this issue, in 1861 the CBH distributed a circular to all local boards of health[11] setting out plans for the construction of two different types of lined cesspools (cesspits) (Figure 2). The MCC archives at PROV include a rare copy of this circular, which is a critical piece of evidence for dating the cesspits of Little Lon because it provides archaeologists with specific measurements and construction techniques for cesspits.[12]

Figure 2: Diagram from the 1861 Central Board of Health circular showing plans for approved cesspits. Source: VPRS 3181/P0, Unit 364 Central Board of Health Circular, p. 2. This and all subsequent images of Melbourne City Council records are held at PROV and reproduced with the permission of Melbourne City Council.

However, cesspits were going out of favour. Earth closets—above-ground pans with dry powdered earth to cover excrement—were coming in. The MCC’s licensed nightmen could collect and empty them, so the MCC began issuing notices to the owners of leaking cesspits requiring them to ‘remedy’ the problem, with earth closets being one of the possible remedies.[13] These notices have not been found in the MCC archives either; however, since the law did not provide for compulsory closure of the old pits, cesspit closures could not have been reliably deduced from them.

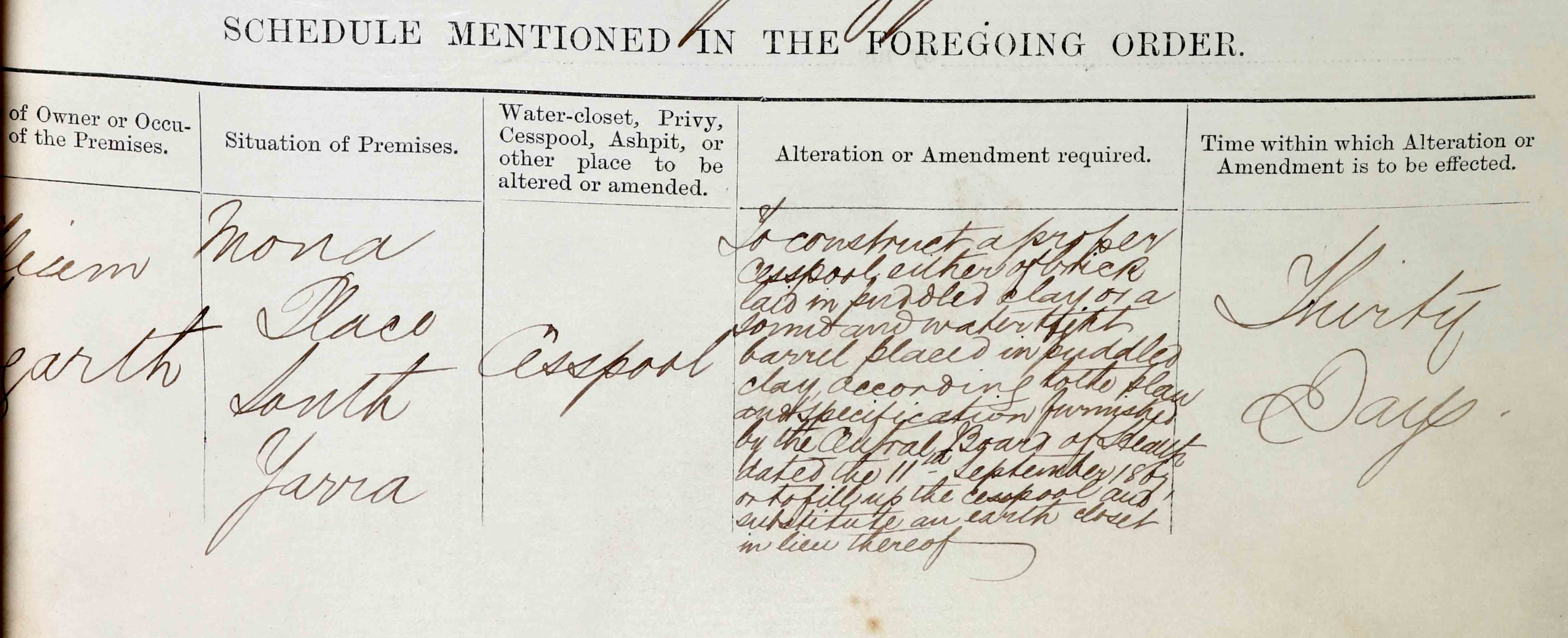

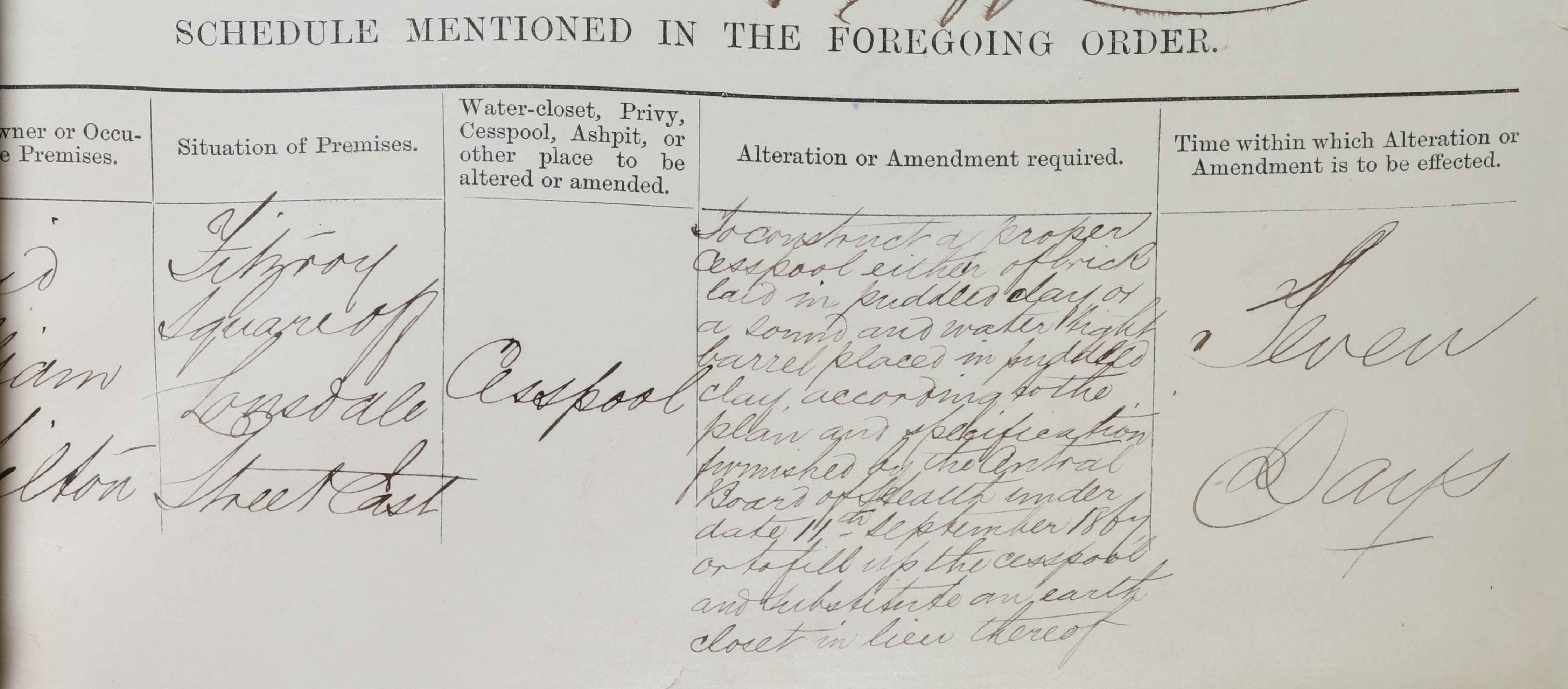

LBH reports and MCC by-laws can be found in the MCC archives at PROV. In addition, the MCC had its own Health Committee and employed inspectors to implement the council’s regulations. In early 1867, Sergeant John Fullerton was appointed as the MCC inspector of nuisances.[14] Later that year, when An Act to Amend the Laws Relating to or Affecting Public Health came into force, every leaking cesspit was deemed an illegal health hazard. As an LBH, the MCC, through its inspector of nuisances, could issue an ‘Order to Amend Cesspools’ and specify the form of proper cesspits to be constructed by property owners or occupiers. It could also demand that overflowing or leaking cesspits be filled in and replaced by above-ground receptacles (or earth closets)—provided the inspector’s orders were formally approved at a meeting of the MCC. Fullerton’s orders usually included instructions to replace cesspits according to the CBH circular, and owners or occupiers were given either seven or 30 days to comply (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Order to Amend Cesspools &c. Source: Health Committee Report 29, 7 December 1868, PROV VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 10, 1868–1869.

Figure 4: Order to Amend Cesspools &c. Source: Health Committee Report 75, 1 February 1869, PROV VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 10, 1868–1869.

Fullerton’s recommendations were always accepted by the MCC and his orders are all neatly filed in the archives held by PROV. However, they are not contained in the Minute Books of Council (VPRS 8910) or among the Proceedings of Council (VPRS 54); nor are they in the Committee Minutes (VPRS 8945) or the Health Committee Minutes (VPRS 4038). Instead, they are housed in a completely separate series: VPRS 3103/P0 Committee Reports. In the period covering the cesspit closures, each year of this series comprises two volumes of reports compiled from all of the standing committees of council, the largest usually being the Public Works Committee.

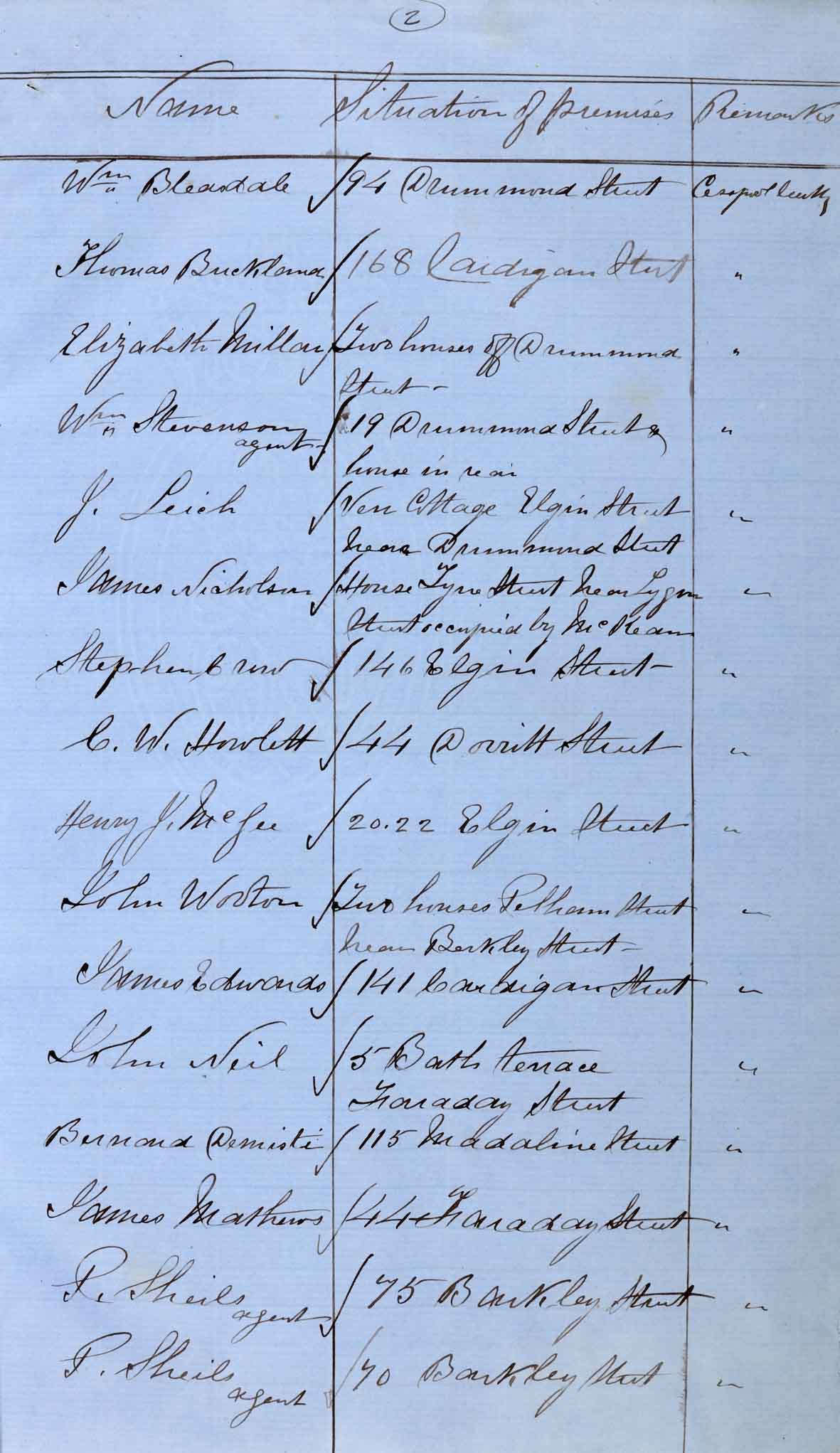

Fullerton did his best to ‘abate the nuisances’ as outlined in the 1867 Act, but owners were inclined to make use of the lengthy council procedures involved in acting on notices to avoid the expense of closure. Probably as a result, the inspector of nuisances issued very few ‘Orders to Amend Cesspools, &c.’ in 1868. However, by the end of that year, Fullerton had a system of lists in place for dealing with ‘leaky cesspools’, ‘defective drains’, ‘low lying land’ and other ‘offensive fluids’. He issued a few notices to remove cesspool drains within seven days (Figure 5), but most of the notices from this period specify that cesspits should be rebuilt according to the CBH’s specifications within 30 days (as in Figure 3).

Figure 5: Order to Amend Cesspool &c. Source: Health Committee Report 38, 14 December 1868, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 10, 1868–1869.

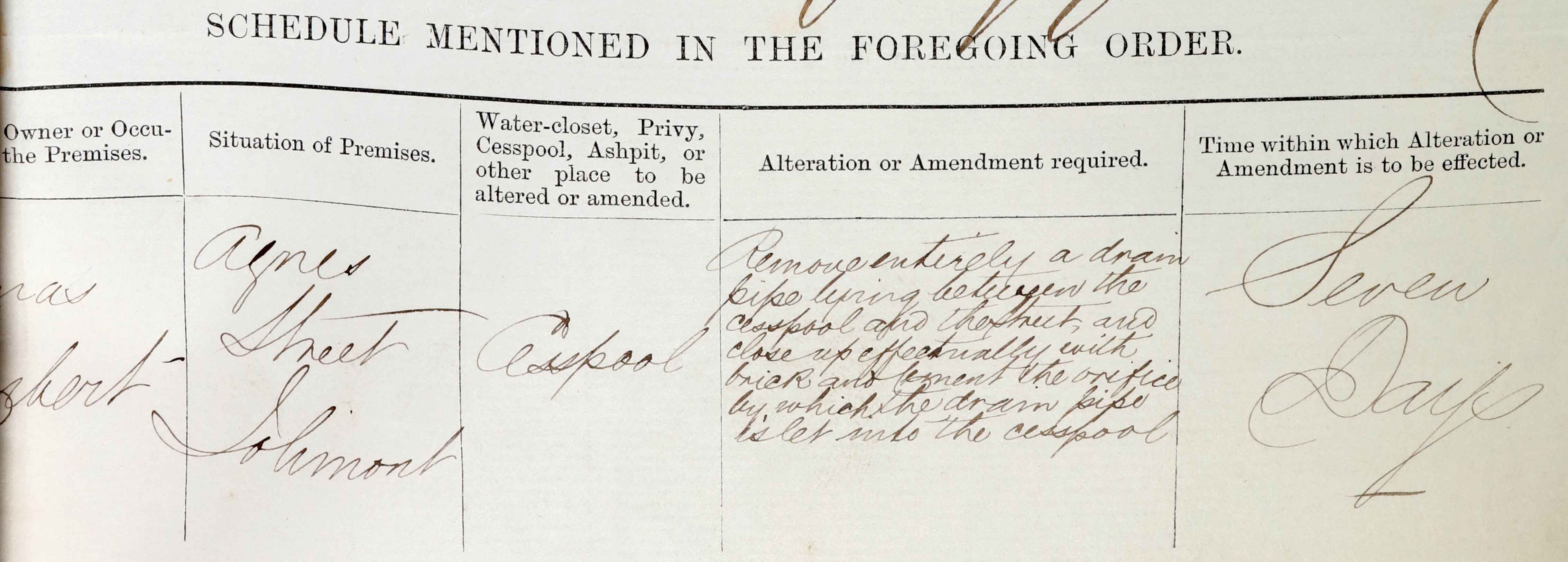

By mid-1869, Fullerton’s leaky cesspool reports had virtually ceased, probably because prosecution was proving difficult and the MCC had started planning their municipal nightpan collection service. On 12 July 1869, the Health Committee forwarded draft specifications to the MCC for the emptying of nightpans from all premises within the city.[15] The collection service commenced on 17 January 1870.[16] Once the MCC nightsoil collections began, Fullerton’s work as inspector of nuisances focused solely on cesspit closures. With enormous and growing public pressure for all cesspits to be filled in, Fullerton issued the first closure order on 31 January 1870[17] (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The first order to fill in a cesspool. Source: Health Committee Report 65, 31 January 1870, PROV VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 12, 1869–1870.

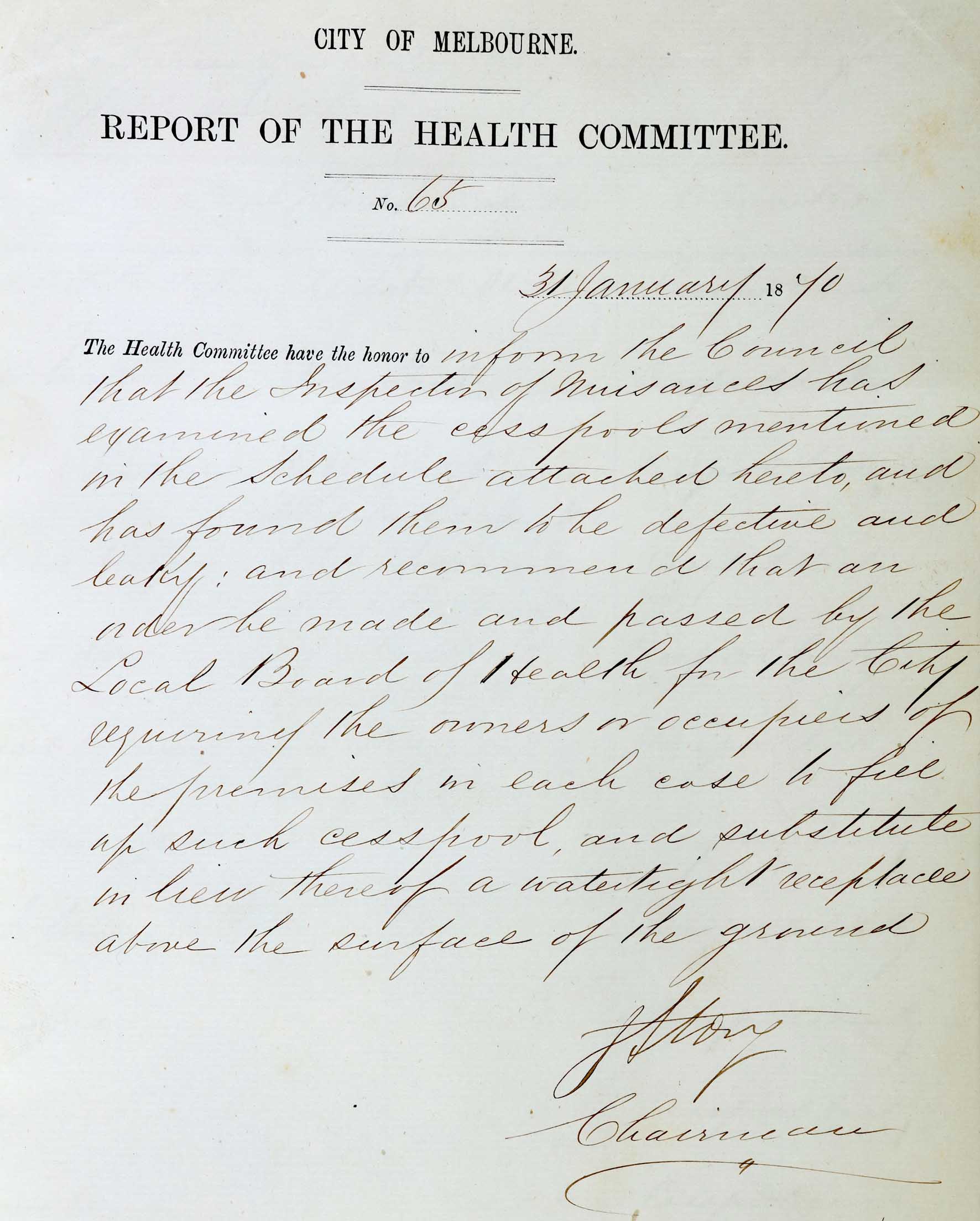

Fullerton quickly developed a reporting style that allowed him to recommend closures in bulk (Figure 7) and, in the first month after nightpan collections began, he recommended the closure of over three hundred leaky cesspits.[18] He continued at that pace throughout 1870. Each order required that the owners or occupiers of the premises fill up the leaking cesspit and install a watertight receptacle (nightpan) above the surface of the ground. From 4 April 1870, the notices gave owners/occupiers only seven days to effect the change.[19]

Figure 7: Order to Amend Cesspools &c. Source: Health Committee Report 2, 28 November 1870, PROV VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 14, 1870–1871.

As valuable to Melbourne’s historical archaeologists as these fortnightly Health Committee reports recommending cesspit closures and drain removals are, they do not provide sufficient detail to immediately identify the property involved—they list owners and/or tenants for each cesspit, but not their specific addresses. Fortunately, the MCC Rate Books (VPRS 5708 P9) record the names of owners and tenants for each allotment with great accuracy. By correlating these two sets of records and testing the result against the archaeological evidence obtained from the cesspit, cesspit closures can often be precisely dated. Unfortunately, not all cesspits were closed by council notice and many cesspits were used by more than one house. At the end of 1870, the Argus noted that the inspector of nuisances had caused the closure of: ‘Single cesspools … 1,029 ; double do., 539; cesspools used by from three to seven houses, 84; total, 1,622, representing 2,527 houses’.[20] With access to Fullerton’s lists recommending these closures, often cesspits serving more than one property can be identified in the records.

Other cesspits were closed by building processes. In 1872, the MCC health officer noted that ‘all the houses built during the same period [1870–71] have, I believe, with hardly an exception, been constructed without the addition of these disgraceful pits’.[21] This comment makes the records in VPRS 9288/P1, MCC Intention to Build Notices, essential reading for archaeologists working with cesspits from this period. A cesspit located below a building that was constructed after notice to the MCC may thus be precisely dated.[22]

Late in 1874, the Argus reported that ‘the cesspits in Melbourne proper have been filled up’.[23] Although MCC records show that this was not entirely correct, the MCC could do nothing about cesspits that were not causing a nuisance. However, a tragedy the following year changed everything. Two nightmen, father and son, were cleaning out a cesspit when they were overcome by ‘foul air’ (carbolic acid gas) and suffocated at the bottom of the pit. At the inquest into their deaths, the city coroner, Dr Youl, made his views clear. ‘The true evil’, he raged, ‘was the cesspits’. The Argus reported that:

[Youl] had held inquests in West Melbourne on the bodies of two children who had been drowned in them, and he had also held two inquests, one in East Melbourne and one in Fitzroy, in which similar accidents to children had occurred. In all these cases he had pointed out the evil of allowing such pits to exist, and the answer—the true answer too—was always the same, that unless a cesspit overflowed neither the corporation nor any one [sic] else had any power to have the pit filled up.[24]

After this latest horror, the coroner, ‘at the request of the jury, promised to bring this matter before the Government through the Central Board of Health, so as to attempt to obtain the abolition of cesspits’.[25] The following month, the Argus ran a substantial series on ‘The Sanatory [sic] Condition of Melbourne’, reporting that there were about 2,000 cesspits remaining in the city.[26] The majority of people had changed over to ‘above-ground receptacles’; however, because it cost people money to do so—and because there was no coercive power in the Act—there were still cesspits fouling the city. As a result of public pressure, The Public Health Amendment Act 1876 legislated the capacity for local health boards (including the MCC) to forcibly close cesspits and prohibit the building of new ones. The inspector of nuisances was given authority to issue closure certificates directly to owners/occupiers without requiring council approval; however, in the first six months of 1877, he only needed to issue notices on about 200 of these[27] before shifting his attention to the provision of a proper number of privies per group of houses, and ensuring that they had proper doors and coverings.[28] Again, VPRS 3103 contains all of these reports. Very few leaky cesspits were recommended for closure in 1878[29] and none thereafter.

Conclusion

This article has shown how the process of cesspit closures in Melbourne can be traced by correlating several sets of MCC records held at PROV. The changeover from cesspits to nightpans was a gradual one throughout Melbourne and, while the process was similar from one municipality to another, the timeframe for the introduction of nightpans varied because each LBH responded differently to orders from the colony’s CBH. For example, Emerald Hill (modern-day South Melbourne), Fitzroy, Prahran and St Kilda all had their own local boards of health and health committees; therefore, dating cesspit closures outside the MCC area would require research in the archives of those relevant council areas. Nevertheless, the records held at PROV provide a complex, rich and irreplaceable resource supporting the endeavours of urban archaeologists working within the early boundaries of the MCC.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on research for the Australian Research Council–funded project A Historical Archaeology of the Commonwealth Block 1850–1950 undertaken by La Trobe University and Museum Victoria (LP 0989224; chief investigators are Professor Tim Murray and Dr Charlotte Smith).

Endnotes

[1] S Hayes & B Minchinton, ‘Cesspit formation processes and waste management history in Melbourne: evidence from Little Lon’, Australian Archaeology, vol. 82, no.1, 2016, pp. 12–24.

[2] See, for example, J McCarthy, ‘Archaeological investigation: Commonwealth offices and Telecom corporate building sites, the Commonwealth Block, Melbourne, Victoria’, Volume 1: Historical and Archaeological Report, Department of Administrative Services and Telecom Australia, Melbourne, 1989; Godden Mackay Logan, Austral Archaeology and La Trobe University, ‘Casselden Place, 50 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, archaeological excavations research archive report’, Volume 1: Introduction and Background, ISPT and Heritage Victoria, Melbourne, 2004; S Hayes, ‘Amalgamation of archaeological assemblages: experiences from the Commonwealth Block project, Melbourne’, Australian Archaeology, no. 73, 2011, pp. 13–24.

[3] P Crook & T Murray, ‘The analysis of cesspit deposits from the Rocks, Sydney’, Australasian Historical Archaeology, vol. 22, 2004, pp. 44–56.

[4] For more detail see Hayes & Minchinton, ‘Cesspit formation processes’, p. 14.

[5] For example, ‘Public health and public works’, Argus, 6 April 1858, p. 6.

[6] AE Dingle & H Doyle, Yan Yean: a history of Melbourne’s early water supply, Public Record Office, Melbourne, 2003, p. 35.

[7] For example, ‘A nuisance’, Argus, 4 August 1859, p. 6 and ‘City Council. Correspondence’, 20 September 1859, p. 5.

[8] ‘Fitzroy Municipal Council’, Argus, 6 September 1860, p. 5.

[9] Records relating to by-laws are held in PROV VA 511 Melbourne (Town 1842–1847; City 1847–ct) (hereafter ‘Melbourne’), VPRS 16940 By-Laws.

[10] JN Hassall, ‘Superintending inspector’s report’, Argus, 13 September 1864, p. 7.

[11] ‘Fitzroy Municipal Council’, Argus, 14 February 1861, p. 5.

[12] Central Board of Health Circular, 1 January 1861, PROV, VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3181/P0, MCC Town Clerk’s Correspondence Files Series 1, Unit 364.

[13] Hassall, ‘Sanitary condition of Melbourne’, Argus, 13 September 1864.

[14] ‘City Council. Weekly meeting’, Argus, 29 January 1867, p. 6.

[15] Health Committee Report 224, 12 July 1869, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 10, 1868–1869.

[16] Meeting 6 December 1869, p. 20, no.15, Health Committee Report 20, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 8911/P1 MCC Proceedings of Council Meetings (MCC 2/1), Unit 1, 1869–1870; ‘Cesspools cleansing’, Argus, 17 January 1870, p. 7.

[17] Health Committee Report 65, 31 January 1870, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 12, 1869–1870.

[18] Health Committee Report 73, 9 February 1870, and Health Committee Report 90, 28 February 1870, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0 MCC Committee Reports, Unit 12, 1869–1870.

[19] Health Committee Report 132, 4 April 1870, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 12, 1869–1870.

[20] J Fullerton, ‘MCC Health Committee’, Argus, 13 December 1870, p. 6.

[21] TM Girdlestone, Report to the Health Committee, 9 May 1872, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 54/P0, MCC Notice Papers and Proceedings of the Council, Unit 19, 1871–1872, p. 1.

[22] MCC Notices of Intention to Build, PROV VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 9288/P1; Hayes & Minchinton, ‘Cesspit formation processes’, p. 17.

[23] Argus,17 October 1874, p. 6.

[24] ‘Two men smothered in a cesspit’, Argus, 16 October 1875, p. 9.

[25] Ibid.

[26] ‘The sanatory [sic] condition of Melbourne’, Argus, 24 November, 1875, p. 6.

[27] Health Committee Report 99, 11 June 1877, VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 26, 1876–1877.

[28] Health Committee Report 141, 24 September 1877, VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 26, 1876–1877.

[29] Health Committee Report 35, 22 February 1878, VA 511 ‘Melbourne’, VPRS 3103/P0, MCC Committee Reports, Unit 28, 1877–1878.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples