Last updated:

‘Attitudes to wife beating in colonial Victoria: the case of Elizabeth Scott, husband murderer’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 17, 2019. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Emma Beach.

This article questions stereotypical assumptions regarding why a colonial woman did not leave a situation of domestic violence in colonial Australia. By analysing the 1863 case of Elizabeth Scott, the first woman to be hanged for a domestic violence related murder, I explore how an understanding of Battered Woman Syndrome would have been a means of lessening her sentence, had the syndrome been recognised at the time. Elizabeth was a victim of repeated and sustained domestic violence, commonly termed ‘wife-beating’ in the 1860s. Similar cases were constantly brought before the local courts and gruesome details faithfully reported in colonial newspapers. Husbands in the Colony of Victoria were routinely arrested and punished for beating their wives in the mid-1800s and into the 1900s. However, the judiciary struggled with how to deter and deal with the abusers. Colonial Victorian common law provided that a husband could subject his wife to punishment or chastisement, so long as no permanent injury was done. Surprisingly, judges dealt with this type of marital violence regularly and often sympathised with the battered partner. Men who assaulted their wives were usually ‘bound over to keep the peace’ by a short period of incarceration or a small fine with the abuser returning home, often to repeat the beatings. Mysteriously, Elizabeth did not prosecute her husband.

Elizabeth Scott is not famous. However, as the first woman hanged in the Colony of Victoria in 1863, you would expect her tragic tale of domestic abuse to be better known.

Elizabeth was a victim of repeated and sustained domestic violence; in the 1860s this type of assault was called wife-beating. To escape her abusive husband Robert, Elizabeth allegedly coerced two lodgers, David Gedge and Julian Cross, into killing him. The murder took place about midnight on 11 April 1863. Charged as an accessory after the fact, Elizabeth was nevertheless, in the eyes of the colonial judiciary, a murderer.[1]

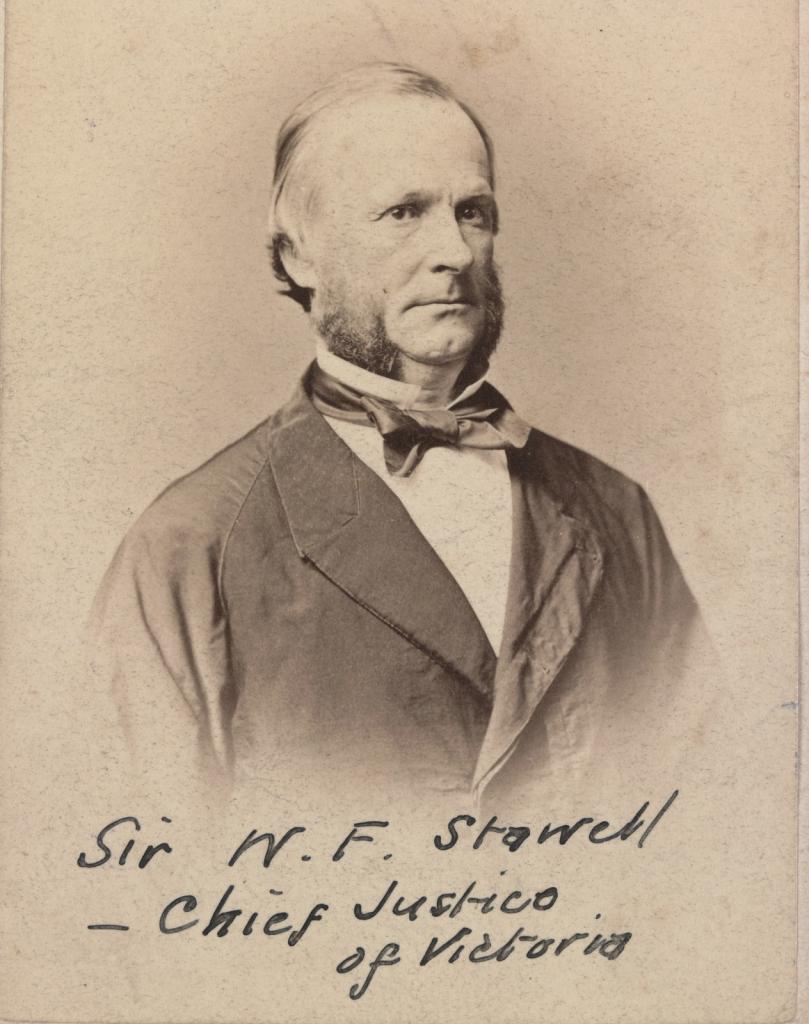

If the Crown prosecution were to try Elizabeth today, she could have presented evidence of having suffered from Battered Woman Syndrome (BWS) as grounds for self-defence in the murder of her husband. Even in 1863, this line of defence would likely have mitigated her sentence given the experience of other abused women. But, unfortunately, Elizabeth’s defence barrister, George Milner-Stephen, made no attempt to introduce her history of abuse as a defence to mitigate her sentence. The presiding judge, Chief Justice William Stawell, therefore, had no other option but to follow the law, and sentenced her ‘to be hanged by the neck until dead.’[2] The Executive Council declined to commute her sentence and the new Governor of the Colony, Sir Charles Darling, did not offer Elizabeth a reprieve. Thus Elizabeth Scott became, on 11 November 1863, the first woman executed in the Colony of Victoria.

Batchelder & O'Neill, photographers, Sir William Stawell – Chief Justice of Victoria, 1864. State Library Victoria, Pictures Collection, H6061.

Attitudes to marriage

At the age of twelve, Elizabeth had been sent to the remote northwest of the colony as an indentured servant on Goomalibee station, which was located near Benalla in Victoria. She was there less than a year before her contract was bought out by Robert Scott, supposedly for the price of six bullocks. Scott, more than 20 years Elizabeth’s senior, then married her, with her mother’s blessing.

Elizabeth was a child bride, married at 13 to a man three times her age. Even in the context of the colonial era, when girls married young, age 13 was very young to be a bride. However, marriage was a desirable state. It was a woman’s entrée to society, the supreme personal and social act of her destiny. For Elizabeth, marriage was a Victorian girl’s pathway to respectability and founding a household of her own:

Marriage was the only acceptable outlet for sexual relations, ensured women’s social, legal and economic dependence ... and maintained the moral fabric of society ... Women’s respectability came through the performance of the role of wife, mother and helpmeet, and marriage was intended to ensure, establish and maintain status.[3]

Elizabeth gained respectability, perhaps, but as a married woman, she was – like her peers – little more than her husband’s personal possession. Women could not sue or take out contracts in their own name and had no rights over property or the custody of their children. It was only in the last century that women have gained the rights to buy, sell and own property, run their own businesses and gain access rights to their own children.

The young mother of two little boys, Elizabeth was dominated by the much older Robert, who in time became an alcoholic and a serial abuser of his child bride. She would later confess ‘she would never have married him except for her mother.’[4] Before colonial newspapers revealed these intimate details, however, the couple ran a successful, if illegal, sly-grog shanty at the crossroads to the Mansfield and Jamieson townships in Victoria’s high country. Fuelled by unlimited access to the shanty’s stock of alcohol, Robert would become seriously drunk and brutally beat his wife. Around midnight on 11 April 1863, he paid the ultimate price for his escalating violence when a single shotgun blast shattered his skull, killing him instantly.

Judicial records

The murder initially puzzled police, as there was no clear motive for the killing. Local gossip led police to suggestions of a liaison between Elizabeth and the lodger David Gedge. Elizabeth’s response to the allegation insinuating her husband was a ‘jealous drunk’[5] was probably unhelpful to her situation; to police, it sounded like she was admitting Robert had something to be jealous about. Police believed they now had their motive for murder.[6]

Victorian judicial records document her tragic story of domestic abuse, but it was the Crown prosecution’s focus on the supposed illicit affair – not the wife-beating – that framed the prosecution’s narrative of the case. The Crown prosecutor convinced the all-male jury that the husband’s murder had cleared the way for Elizabeth’s affair with David Gedge.

She was labelled an adulteress and depicted as a ‘female monster’ who had lured Gedge and her cook Cross to kill her husband with pretty promises.[7] Although there was no evidence that she had fired the fatal shot, Elizabeth was characterised by the prosecution as the cold-hearted instigator of the killing in a case that tantalised the Victorian public with its story of adultery and murder.

During her trial, Elizabeth’s legal team was inept in failing to offer an alternate explanation for her alleged complicity in the murder. The only defence her barrister offered was ‘that she didn’t look like a murderer’.[8] The public record tells us that Elizabeth hid her shame behind what appeared to the authorities to be a cool exterior. When questioned by the police and the magistrates, she played down the battering and the threats to her life (this is no different from today where less than 20 per cent of women who have experienced violence report it to authorities).[9] When confronted with similar situations, victims often deny violence or psychological abuse has occurred.[10] Elizabeth was not dissimilar; in fact, she sought to protect her abuser. In her statement to the police, Elizabeth said, ‘My husband ... used to blow me up now and then.’[11] In colonial Victoria, ‘to blow one up’ meant to beat them. Robert even ‘threatened to take her life’.[12] Elizabeth covered up her humiliation with a brave offhand remark: ‘but I never took any notice of it’.[13] Like most victims, Elizabeth modified her statements and made excuses for her husband’s violence – ‘he always did it’ and ‘he never meant it, but he was always sorry for it’.[14] But perhaps tellingly, ‘There was always a pistol lying on the shelf within his reach.’[15]

Why did Elizabeth seem to not view her husband’s threats as a serious risk to her life? The answer is easy to grasp. She had nowhere to go, and no-one she could ask for help. When Robert attacked Elizabeth with insults, taunts or accusations, there were no neighbours to corroborate her stories other than Gedge and Cross. For their part, they heard, saw and said nothing. Only later they admitted to hearing heavy falls and dull thuds, and the later declarations of affection from her husband. It is also possible they considered Robert’s apologies a satisfactory conclusion to the beatings. The indifference they initially showed was unremarkable for the times in which they lived.

Public perception, moral values and the law

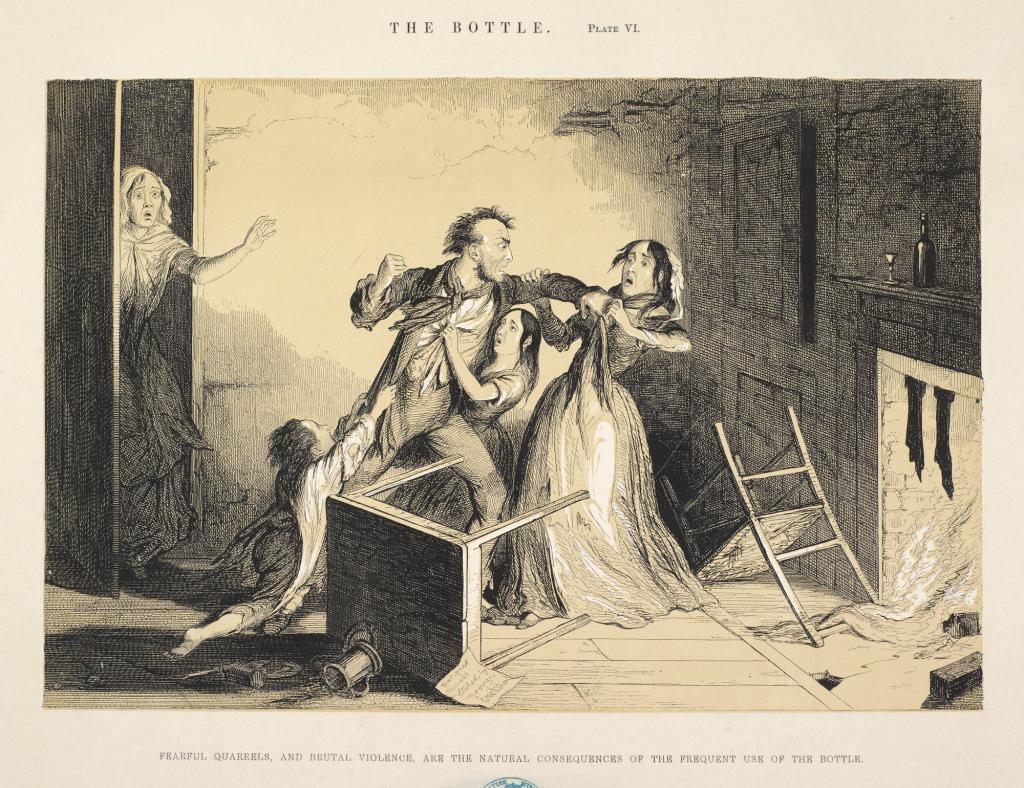

Of course, in the Victorian era, marriage was sacrosanct, and no-one would interfere in the hierarchical relationship of husband and wife. Also, Victorian society conditioned colonial wives not to expose their shame to strangers. However, the press did report the prevalence of wife-beating in society, usually ‘with a distinct mix of moral approbation and lurid detail’[16] about both perpetrators and victims.

‘Fearful quarrels, and brutal violence, are the natural consequences of the frequent use of the bottle’, George Cruikshank, Plate VI, The Drunkard's Children: A sequel to The Bottle, In eight plates, 1914. British Library, General Reference Collection HS.74/1107.(1.).

As the head of the household, Robert’s status entitled him to moderate ‘correction’ of his wife. His violent blows were not entirely illegal. Too often his state of intoxication was the excuse for his actions. Colonial Victorian common law provided that a husband could subject his wife to punishment or chastisement, so long as he inflicted no permanent injury.

In a reflection of the moral values of society, if wives did seek help, judges took a dismal view of abuse and the abuser. Most courts sought to protect women within the confines of the law, but 1860s legislation did not provide judges with effective remedies for wife-beating.

The only recourse judges had were to prescribed fines and incarceration as deterrents, ‘binding the offender over to keep the peace’.[17] The authorised penalty for common assault was a fine not exceeding £5 and in default, imprisonment not exceeding two months.[18] For example, Malcolm Littlejohn appearing in court in December 1858,

... appeared very sorry for what he had done, and stated that he would sign the pledge and never abuse his wife in future. The bench accepted his promise, and ordered him to find two sureties in £25 each to keep the peace towards his wife for the next six months.[19]

It is likely that Elizabeth did not ever charge her husband with wife-beating because she had seen first-hand the agony her sister went through prosecuting her alcoholic husband in the Melbourne courts. After completion of his sentence, the protagonist simply returned home to his wife and children – chastised or resentful but unchanged in his behaviour. In reality, the colonial courts were powerless to stop the cycle, and her sister’s only option therefore was to leave with a new man.

Like today we know that most wife-battering is hidden from view. On average, women are assaulted 35 times before their first police contact.[20] Perhaps the answer to why Elizabeth did not charge her husband is much simpler: she may have thought that no-one from the local police camps – who were Robert’s shanty customers – would believe her.

Certainly, wife-beating was an assault but it was typically treated as a ‘one-off altercation rather than an ongoing pattern of violence’.[21] Colonial courts identified spousal violence as a specific type of abuse but had no specific legislation to deal with it. Magistrates conceded that justice to the husband spelled injustice to the wife and children. So even when the abuser was brought before the court, the wife often changed her mind when faced with the personal cost of a husband’s conviction, frequently stating, ‘I do not want to prosecute’.[22] Wives worried about the impact upon themselves of the court’s judgement: ‘if my husband is sent to gaol I have no means of support but by my own labour’.[23] If she sought redress, or if the courts forced redress upon her, she must endure further suffering deprived of the breadwinner, and in seeing her children deprived. Like many women, Elizabeth suffered in silence.

Battered Woman Syndrome (BWS)

Legislation in the twenty-first century better recognises the pattern of violence which Elizabeth endured – and her subsequent psychological state – as Battered Woman Syndrome (BWS). Since 1991, women victims of abuse in Australia can invoke BWS as evidence supporting self-defence against their abuser. Psychologist Lenore Walker developed the theory to describe the behaviour and state of mind of a woman who kills her violent partner.[24] Usually, this line of self-defence must prove that the accused’s life or physical well-being was threatened and they responded with like force. The introduction of evidence of BWS as a defence strategy has assisted the courts in understanding why females resort to using stealth or delayed tactics instead of combating the abuser head on.[25] Physically and mentally, the victim of BWS may not be up to facing her abuser directly. For many women like Elizabeth, she has had no means of physically defusing any threat against her life.[26]

For example, years of living with a violent person conditions the woman to an acute perception of danger and the need for self-protective responses such that she may perceive danger where others might not. Further, her only opportunity to defend herself violently may come when her partner is sleeping or passed out, or when she has access to a weapon like a knife or gun.[27]

Had Elizabeth been tried today, she may have employed this defence by producing evidence that she suffered from Battered Woman Syndrome. BWS explains why, in her demoralised situation, the female’s reprehensible actions seemed reasonable to her at the time. In 1863, this kind of defence would not have saved Elizabeth from a murder conviction but could have saved her from the sentence of execution.

In colonial newspaper reports, only a few enlightened judges were recorded to have taken into account the woman’s history of being abused as a defence argument in partner-murder cases.[28] Their judgements are reflected in mandatory death sentences being commuted to life imprisonment and hard labour. In one such case, just three years before Elizabeth’s trial, Mrs Ann Hayes had been convicted of the murder of her husband. Chief Justice William Stawell observed that her crime was ‘the most disgraceful of its class – the murder of a husband by a wife.’[29] As in Elizabeth’s case, the prosecution had sought to explain the unwomanly behaviour of the defendant in killing her husband by alleging adultery, but due to Mrs Hayes’s battered history, the trial judge took the abuse into account and her sentence was mitigated. More often, women who had been abused and killed their husbands did not generally receive mitigated sentences, but had to rely on petitions to the Governor pleading their case for a commuted sentence.

Adultery and the law of coverture

The reliance on illicit affairs as a motive surfaced continually in colonial cases where abused women conspired to kill their spouses. In Elizabeth’s case, the Crown prosecutor made much of the defendant’s involvement with a man outside the marriage. And, like the general public, he presumed the motive for the killing was sexual in origin. Other colonial women condemned in this fashion included Annie O’Brien, who was convicted of poisoning her de-facto husband so she could run off with another man,[30] and Selina Sangal, who was sentenced to hang for conspiring with a lover to kill her husband – although she ultimately avoided the noose.[31] The prosecution had painted these women simply as adulteresses, not taking into account their histories as abused wives. As in Elizabeth's case, the prosecution argued that the removal of the husbands had cleared the path for illicit affairs to flourish. This was an easy case to make, especially as no other motive or history of abuse was presented to the Victorian all-male juries. Certainly no-one took the trouble to educate juries about the traumatic psychological state the defendant was in at the time of the murder. Jurors of today are educated in the nature of BWS to help them understand the violent lead-up of events and the victim’s psychological state at the time of the partner-murder.

In colonial times, not unlike today, the murder of a man by a woman was rare.[32] This was typically seen by all-male juries as against the natural order, and they commonly considered it ‘an extreme affront to the patriarchy’.[33] In Elizabeth’s case, there was a further impediment to a just course: a colonial doctrine prohibited the accused from giving evidence under oath in their defence if they had a barrister. Even if Elizabeth’s barrister had her take the stand, he would have been prohibited by the law of coverture.[34] This meant that Elizabeth did not have the opportunity to defend herself in person because the status of femme covert or married woman applied to her. Under the law, Elizabeth had become her husband’s property upon her marriage, and consequently she did not have a separate legal status. Hence, the law considered her actions petit treason against her husband; as a wife, she was both protected and harmed by her married status.

Elizabeth’s silence, whether enforced or not through her status as femme covert, made it easy for the prosecution to insinuate the idea of her as the scheming older woman, beguiling her alleged younger lover, David Gedge, and co-defendant, Julian Cross, to murder her husband. Her barrister did not present any evidence supporting Elizabeth’s history of abuse as a reason for killing her husband. Had he done so, it may have enlightened the jury as to why Elizabeth may have believed this was her only option to escape his blows.

Three stages of Battered Woman Syndrome

According to the notion of Battered Woman Syndrome, violent relationships go through three stages: a period of mounting tension, an acute battering incident, and a period of loving contrition.[35] Some professional researchers in the field argue that not all women experience the repetitive three stages in the cycle of violence, and not all cases of domestic violence fit neatly within these three stages. There is also no clear demarcation of when stage one becomes stage two. The psychologist Lenore Walker surmised ‘that each stage will repeat over time with the violence increasing in severity.’[36] In Elizabeth’s case, the battering had turned into deadly threats, ‘During his late illness, he has threatened to take my life ...’[37]

Stage one: a period of mounting tension

Every domestic violence event is unique. Research shows that domestic violence occurs when a perpetrator exercises power and control over another individual.[38] From the evidence available, Elizabeth had lived with Robert’s controlling psychological and physical abuse for years. Arguably, no police statements could have exposed the invisible, intangible constant fear Elizabeth experienced. Elizabeth came to disclose ‘that she was afraid to leave the place without him.’[39] She honestly believed he would come after her. What we now know is that when women say they are too terrified to leave the marriage, they ‘may be very accurately assessing their own risk.’[40] A recent study has supported Elizabeth’s intuition, finding that ‘such men are known for their relentless pursuit of their victims and that they are resistant to court control’.[41]

Stage two: an acute battering incident

Several witness statements provide evidence of wife-beating being present in Elizabeth’s case, when she said her jealous drunk of a husband often ‘assaulted her ... He was always drunk when he threatened to take my life.’[42] During that fateful evening, her alleged lover David Gedge was heard by Julian Cross to exclaim that ‘Bob is scolding the missus [again]!’[43] As Lenore Walker’s research highlights, violent episodes increase with each incident.

Stage three: a period of loving contrition

Robert apologised for his threats and violent behaviour, and ‘when he was sober, he was always sorry for it’,[44] and he became a loving and apologetic husband after his abusive periods. This was the fairytale romance stage Elizabeth had craved, defined as the honeymoon stage in BWS. Elizabeth desperately wanted to believe him, but the apologies did not last long. Robert’s loving behaviour soon deteriorated when he returned to the bottle, and the wretched cycle of wife-beating began again.

Learned helplessness

Elizabeth had no way of knowing when Robert’s violent abuse would return and when it would escalate. ‘This exacerbates her state of terror’ and reinforces her ‘learned helplessness’.[45] Learned helplessness is the term applied to individuals who have endured situations of chronic terror; as a consequence of which they lose their ability to make good life choices. For some, domestic violence psychologically prevents a victim leaving the abusive relationship; suffering at the hands of a wife-beater is no different. In fact, this ‘learned helplessness’ goes part way to explain Elizabeth’s reluctance to leave the relationship due to the effects of continual abuse.

The landmark case of R v Raby, 130 years later, is instructive in circumstances where a wife – a victim of BWS – stood trial for murdering her abuser, and the syndrome was drawn upon in evidence for her defence. Like Elizabeth, she had suffered degrading abuse over a number of years. In R v Raby, an expert was called to give evidence before the jury as to how this degradation might have led the wife to arrange her husband’s murder. The jury found the wife not guilty of murder, but guilty of manslaughter on the grounds of provocation. It is worth recalling that being systematically threatened and ‘blown up’ were Elizabeth’s grounds for provocation.

In the 1860s alienists (as early psychiatrists were called) were not called upon to give evidence on Elizabeth’s psychological state. Even if able to be called upon, these professionals would not have been able to explain to a jury why Elizabeth did not leave her abusive relationship. It is only now that psychiatrists would be asked to explain to the court how Elizabeth’s actions exhibited the signs of BWS and constituted evidence for self-defence by describing what is a reasonable action for someone in an abusive situation.[46] In Elizabeth’s mind, it was entirely reasonable that she could not leave. There was no easy way out:

The average member of the public can be forgiven for asking: Why would a woman put up with this kind of treatment? Why should she continue to live with such a man? How could she love a partner whom beat her to the point of requiring hospitalisation? We should expect the woman to pack her bags and go. Where is her self-respect? Why does she not cut loose and make a new life for herself?[47]

Of course, this is a twenty-first century view. For a colonial woman, expectations and options were markedly different than they are today. If she had left, where would she have gone? What would she have done for an income? And what about her children? In reality, the colonial wife may have had no other abode to move to, or by virtue of emigration, no family or close friends for support. Women’s support groups did not exist. Women’s refuges, and financial and emotional assistance outside the narrow circle of family life also did not exist.

A woman’s isolation in the bush would have been an additional barrier to leaving. Living in the bush, Elizabeth could not just rent a room in a boarding house. Her reputation was no doubt already sullied as the mistress of a sly-grog shop; to run away would have ruined her socially beyond redemption.

Another option to escape her violent marriage was divorce.[48] By 1863 males in all colonies were allowed to petition for divorce on the grounds of the wife’s adultery. Later amendments to the Marriage Act allowed women to petition for divorce on the grounds of adultery or cruelty, drunkenness and criminality. This was rare and costly; often in the upper classes, husband and wife lived apart to save the embarrassment of public proceedings. Generally, divorce was viewed as ruinous to both parties and scandalous for the family, and it meant Elizabeth would have had to prove physical abuse like rape or incest. If the courts did grant a divorce, she could not remarry and re-establish a family unit with her own children. Elizabeth would not have been able to keep them with her; they were her husband’s property. And even though children were the husband’s possession, society would look upon her as having abandoned her children. Furthermore, any income she earnt to support her estranged living arrangements would not have been solely hers, and her husband would have been able take it away from her.

So, a victim of BWS, Elizabeth stayed with her abusive husband.[49] Researchers have identified that a trigger typically breaks the cycle, culminating in the final reckoning between the abuser and the victim. It may be only a small, seemingly negligible incident to an outsider, but to a terrified victim of abuse, it may be the last devastating incident they can handle.

Flight of femininity

Throughout the trial and leading up to her execution, Elizabeth’s apparent insouciant demeanour engendered no sympathy. Unfortunately,

some women are ... treated more harshly by the criminal justice system because they fail to live up to stereotypical female roles.[50]

It could be said that ‘what was female, was subject to more scrutiny than what was male’.[51] Simply put, Elizabeth’s outward demeanour did not conform to expectations of Victorian propriety. She did not cry, nor break down in hysterics, and she was consequently condemned for her ‘cool’ behaviour by colonial officials and the public. The police reported she ‘exhibited ... apparent indifference to the death of her husband and to her own position.’[52] To the press, she did not act like a ‘proper woman’[53] mourning her husband, nor fearing for her life during the trial and afterwards. As the Leader newspaper reported, Elizabeth ‘appeared quite unmoved ... she alone preserved an air of the most perfect unconcern as to what was passing around her.’[54]

Seemingly withdrawn and aloof, Elizabeth outwardly appeared to show a callous disdain for her husband’s death. The Herald printed that she was no longer a woman, having been ‘unsexed by her crimes’.[55] Unsympathetic to her plight and ignorant of her psychological state, Justice Stawell condemned Elizabeth’s demeanour as that of a traitor to womanhood.

Sentencing and execution

After Elizabeth’s conviction for murder, trial judge Justice Stawell handed down the mandatory sentence of death. In his sentencing remarks, he concluded Elizabeth ‘acted contrary to the expectations of her gender and betrayed her “feminine” role.’[56] A woman had never been executed in Victoria until this time; women previously condemned to death had had their sentences commuted to periods of imprisonment. This happened to Mary Silk, for example, who successfully argued self-defence in killing her husband when he threatened to shoot her.[57] Silk’s defence counsel had raised her history of abuse and saved her from execution. Elizabeth, therefore, had strong grounds for thinking that through an appeal to the Governor of Victoria, she could escape the hangman’s noose.

On 11 November 1863 the closing scene of the tragedy took place. Standing on the gallows platform, Elizabeth realised there was no reprieve forthcoming from the Governor. Neither her gender nor her youth would save her. In the last desperate moments she pleaded with her co-convicted, David Gedge – ‘Davey, will you not clear me?’ In his silence she had her answer. The hangman pulled the lever; Elizabeth Scott was hanged by the neck until dead.

The problem remains

In the twenty-first century, though the terminology has changed over time from wife-beating to domestic violence, the problem remains the same. Under the Crimes Act 1958, Victoria has abolished the common law rule that defensive force must be proportional to the threatened harm that is being defended against – but only for domestic violence cases. This means it is now not necessary to prove that the accused is responding to an imminent, immediate threat of violence.

Since 1991, cases presented before the courts have used self-defence, provocation, duress and Battered Woman Syndrome as part of a defence for victims who have been tried for killing their partners.[58] In 2005, the Victorian Parliament introduced a new offence of ‘defensive homicide’ for those who kill in response to domestic violence.[59] It is the only state where in cases where family violence is alleged, a wide range of evidence is relevant to the subjective and objective aspects of the self-defence requirements. The legislation also makes it clear that violence includes not only physical and sexual abuse, but also psychological abuse, intimidation, harassment, damage to property, threats, and allowing a child to see, or putting them at risk of seeing, their parent being abused.[60] In accordance with BWS, it specifies that violence can comprise a single act or a pattern of behaviour, which can include, in turn, acts that in isolation might appear trivial to others.

Australia’s first Royal Commission into Family Violence handed down 227 recommendations which the Victorian Government has committed to implementing over the next ten years. It focuses on building a future where Victorians will live free from family violence. For Elizabeth Scott, the recommendations came 150 years too late.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VPRS 7583/P1 Register of Decisions on Capital Sentences, Unit 1, 1851–1889.

[2] ‘Murder Trial’, The Ovens and Murray Advertiser, Saturday 24 October 1863.

[3] HJ Whiteside, Women and representations of respectability in Lyttelton 1851–1893, Masters Thesis, University of Canterbury, 2007, available at <https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/951/thesis_fulltext.pdf>, accessed 7 November 2019.

[4] Arsenic murderer Louisa Collins, told a similar story, marrying in 1865 as ‘her mother thought it would be a good match’, see Caroline Overington, Last Woman Hanged, Harper Collins, Sydney, 2014, chapter 1.

[5] PROV, VPRS 30/P0 Criminal Trial Briefs, Unit 261 (1863), Case 2, Queen v. Scott, Deposition of Ellen Ellis, Coroner’s Inquest at note 15.

[6] Ibid., Coroner’s Inquest at note 11.

[7] Ibid., Sergeant J Moors to officer-in-charge, Benalla Police, 27 October 1863.

[8] George Milner-Stephen, ‘Murder trial’, letter to the editor of Ovens and Murray Advertiser, Saturday 24 October 1863.

[9] Victorian Law Reform Commission, Defence to Homicide, Final Report, Victorian Law Reform Commission, Melbourne, 2004, pp. 167–68, ‘Myth 6’ and ‘Myth 7’, available at <https://www.lawreform.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/VLRC_Defences_to_Homicide_Final_Report.pdf>, accessed 7 November 2019.

[10] Ibid.

[11] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 261 (1863), Case 2, Queen v. Scott, Deposition of Elizabeth Scott, Coroner’s Inquest at notes 8–9.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., Deposition of Elizabeth Scott and Deposition of Ellen Ellis.

[16] Zora Simic, ‘Towards a feminist history of domestic violence in Australia’, Australian Women’s History Network website, posted 24 November 2016, available at <http://www.auswhn.org.au/blog/history-domestic-violence/>, accessed 7 November 2019 (quoted with permission).

[17] Crimes Act 1958 (Vic), Part I, Offences against the Person sections 3–70.

[18] Ibid.

[19] ‘Police’, Age, 30 December 1858, p. 6.

[20] This figure has been cited in UK reports: D Ward, ‘When all you can do is run for your life’, Guardian, 13 December 2003, available at <http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,1106182,00.html>, accessed 7 November 2019. In Australia, the ABS reported in its 1996 survey that 18.6% of women who had experienced physical assault by a man and 14.9% of women who had experienced sexual assault by a man, in the previous 12 month period, reported the last incident to the police. Women who experienced violence by a current partner were least likely to have reported the incident to the police: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Women’s Safety Australia, Catalogue No 4128.0 (1996), pp. 28–29, Tables 4.5–4.10.

[21] J McEwan, ‘The legacy of eighteenth-century wife beating’, Australian Women’s History Network website, posted 4 December 2016, available at <http://www.auswhn.org.au/blog/18th-c-wife-beating/>, accessed 7 November 2019 (quoted with permission).

[22] ‘Wives decline to prosecute’, Argus, 10 July 1928, p. 14.

[23] Ibid.

[24] L Walker, The Battered Woman, Harper & Rowe, New York, 1979; L Walker, The Battered Woman Syndrome, Springer, New York, 1985.

[25] Patricia Easteal, Less Than Equal: Women and the Australian Legal System, Butterworths, Chatswood, NSW, 2001, chapter 3.

[26] Elizabeth Sheehy, Julie Stubbs and Julia Tolmie, ‘Defending Battered Women on Trial: The Battered Woman Syndrome and its Limitations’, Criminal Law Journal, vo. 16, no. 6, 1992, pp. 174, 369.

[27] E Schneider, Battered Women and Feminist Lawmaking, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000, see note 117, p. 146.

[28] PROV, VPRS 7583/P1, Unit 2, 1889–1944.

[29] R v. Hayes reported in Bendigo Advertiser, 6 March 1860, p. 2 and Argus, 1 March 1860, p. 5. See also Petition for Commutation of Sentence of Ann Hayes from the Inhabitants of Sandhurst in PROV, VPRS 264/P0 Capital Case Files, Unit 2, Anne Hayes (1860).

[30] Trial Transcript, Memorandum of Judge Hartley Williams, and Melbourne Police Department letter dated 26 August 1892, in PROV, VPRS 1100/P2 Capital Sentence Files, Unit 1, Annie Louisa O’Brien (1892).

[31] Memorandum of John Madden, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria, PROV, VPRS 1100/P2, Unit 3, August Tisler (1902), and Selina Sangal (1902).

[32] Paula Jane Byrne, Criminal Law and Colonial Subject, Studies in Australian History, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993, p. 102.

[33] Peter King, Crime, Justice and Discretion in England 1740–1820, Oxford University Press, Oxford (UK), 2000, p. 193.

[34] The High Court of Australia recently, in 2011, overturned the right to refuse to give evidence against one’s spouse at common law in Australian Crime Commission v. Stoddart [2011] HCA 47, 244 CLR 554 [High Court of Australia].

[35] Victorian Law Reform Commission, Defence to Homicide, p. 162, available at <https://www.lawreform.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/VLRC_Defences_to_Homicide_Final_Report.pdf>, accessed 7 November 2019.

[36] Walker, The Battered Woman.

[37] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 261 (1863), Case 2, Queen v. Scott, Deposition of Elizabeth Scott.

[38] Royal Commission into Family Violence, Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan For Change, Victorian Government, Melbourne 2017, available at <https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-07/Ending-Family-Violence-10-Year-Plan.pdf>, accessed 7 November 2019.

[39] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 261 (1863), Case 2, Queen v. Scott, Deposition of Elizabeth Scott.

[40] Z Rathus, There Was Something Different About Him That Day: The criminal justice system’s response to women who kill their partners, Women’s Legal Service, Brisbane, 2002, p. 3.

[41] Law Society of Western Australia, ‘The Law Society of Western Australia's response to the Women Lawyers of Western Australia’s 20th Anniversary Review of the 1994 Chief Justice’s Gender Bias Taskforce Review’, 23 August 2016, available at <https://www.lawsocietywa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2016NOV01_Law-Society-Directions-Paper.pdf>, accessed 19 November 2019.

[42] PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Unit 261 (1863), Case 2, Queen v. Scott, Deposition of Ellen Ellis, Coroner’s Inquest at note 15.

[43] ‘The Murder in Mansfield, The adjourned enquiry’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 7 May 1863, p. 2.

[44] PROV, VPRS 30/P0,Unit 261 (1863), Case 2, Queen v. Scott, Deposition of Elizabeth Scott, Coroner’s Inquest.

[45] Walker, The Battered Woman, pp. 55–65.

[46] J Scutt, ‘The Incredible Woman: A Recurring Character in Criminal Law’, Women’s Studies International Forum, vol. 15, issue 4, July–August 1992.

[47] R v Lavailee [1990] Judge J. Wilson 1 SCR852, 76 CR(3d), p. 329 [Supreme Court of Canada].

[48] Ruth Teale, Colonial Eve, sources on women in Australian, 1788–1914, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1978, pp. 166–68.

[49] Rathus, There Was Something Different, p. 3.

[50] Byrne, ‘Criminal Law and Colonial Subject’, p. 102; Robyn Lincoln and Shirleene Robinson, Crime Over Time: Temporal Perspectives on Crime and Punishment in Australia, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2010.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Report on Prisoners Cross, Gedge & Scott Sentenced to Death, in PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 3, Julian Cross / David Gedge / Elizabeth Scott (1863).

[53] Ibid.

[54] ‘Execution of the Beechworth murderers’, Leader, 14 November 1863, p. 6.

[55] ‘The Mansfield Murderers’, Herald, 2 November 1863, p. 2.

[56] ‘Murder Trial’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, Saturday 24 October 1863.

[57] Report on the Case of Mary Ann Silk by Judge William Stawell, in PROV, VPRS 264/P0, Unit 11, Mary A Silk (1884).

[58] Runjanjic & Kontinnen v. R (1991) 56 SASR 114 [Supreme Court of South Australia]. This case was the first to introduce evidence of Battered Woman Syndrome in Australia.

[59] Crimes Act 1958 (Vic), sections 9AC–AD.

[60] Ibid., section 9AH(4).

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples