Last updated:

‘Deleting freeways: community opposition to inner urban arterial roads in the 1970s’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 18, 2020. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Sebastian Gurciullo.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article explores community resistance to the F2 freeway proposal that emerged in the wake of the 1969 Melbourne Transportation plan. Drawing on published work in urban social history and urban policy analysis, as well as a wide range of archival sources, it provides an account of the defeat of this freeway proposal through community protest and the exertion of political pressure on government. It argues that the defeated proposal had been generated as part of a broader road-building consensus in Melbourne that gave little consideration to community impacts and the possibility of alternative transport solutions—a consensus that largely survives to the present day despite occasional backdowns such as the one explored in this article.

Roads equals transport

This article examines an attempt to challenge the ascendancy of roads policy networks in Melbourne’s urban planning bureaucracy and the Victorian Government, and the substitution of massive roads construction for true transport planning in Melbourne. The 1969 Melbourne Transportation plan was the ultimate expression of this ascendancy. Though more than 50 years old, it has continued to shape the broad parameters of how mobility has been defined and delivered in Melbourne until the present day, leaving public transport development relatively stagnant for much of that time.

The ascendancy of roads construction in the form of a massive freeway grid covering the whole metropolitan area was challenged most successfully in the inner suburbs of Melbourne, particularly in the inner north: Carlton, Collingwood, Fitzroy, Brunswick, Coburg, Northcote, Clifton Hill and East Melbourne. In these suburbs, demographic changes, particularly the influx of professionals, crystallised an effective coalition of community resistance movements. The F2 freeway, proposed as a cross-city north–south link between the Hume Highway in the north and the Princes Highway in the south-east made it a crucial battleground for this challenge to the ascendant policy networks that were seeking to impose freeway construction as the primary solution for delivering mobility in the city. Community groups were politically effective in demonstrating that freeway construction in these suburbs would seriously damage and disrupt certain community amenities, intangible qualities and aesthetics of the neighbourhoods concerned, and that these aspects could not be ignored when developing mobility solutions in these areas. The community activism and anticipated electoral backlash forced the Victorian Government to formally abandon much of the proposed freeway network, even if the policy consensus remained largely unchanged and influential for years to come.

The article draws upon research into the history of demographic changes in Melbourne’s inner city, particularly the influx of younger generations of educated people who were drawn to the architecture, lifestyle and cosmopolitan flavour of these inner neighbourhoods. The work of urban social historians such as Graeme Davison[1] and Seamus O’Hanlon[2] provides us with an understanding of the economic, social and demographic transformation of Melbourne during the 1970s, while more specialist histories of road-building and infrastructure authorities by Tony Dingle and Carolyn Rasmussen[3] and Max Lay[4] have shown how these agencies shaped and implemented transport in Melbourne in the early 1970s. The works of Renate Howe and David Nichols[5] in relation to activism in the inner city are a valuable source for informing the discussion of the freeway protests that feature in this article. In addition, planning and policy analysis from Michael Buxton, Robin Goodman and Susie Moloney,[6] John Stone,[7] Geoff Rundell,[8] and Crystal Legacy, Carey Curtis and Jan Scheurer[9] help us understand the power and resilience of the road-building hegemony in Melbourne. These authors have been particularly useful for drawing attention to the policy planning networks in Melbourne that solidified around a roads construction consensus across government and planning authorities.

Much of this literature has dealt with the resistance to freeways in the inner north, particularly the Eastern Freeway that was initially proposed to cross through Collingwood, Fitzroy, Carlton and beyond. Less attention has been given to the F2 freeway proposal. The main contribution of this article is its detailed examination of the documentary evidence surrounding the F2 proposal, both the decisions and actions from government and the planning authorities on the one hand, and the efforts of community action groups and citizens in resistance on the other.

The 1969 Melbourne Transportation plan

December 2019 marked the fiftieth anniversary of a visionary and radical transportation plan that sought to impose a new urban form on Melbourne. Though called a transportation plan, it was heavily skewed to building roads, particularly freeways. Following the release of the plan, on 18 December 1969 the Age reported that the road component was costed at $2.2 billion (a very considerable sum in 1969) out of a total of $2.6 billion ($242 million for rail projects, $55 million for tram upgrades and $58 million for bus upgrades).[10] In recent years, a number of transportation experts have observed that the plan still remains highly relevant and influential for understanding current policy and expenditure priorities. This is the case because the underlying policy networks have resisted change despite some incoming governments having campaigned on advancing public transport priorities at elections. Therefore, the plan expressed a highly influential policy consensus that has remained largely unchallenged until the present. It rested on two interlocking assumptions that ignore the problem of induced demand. First, that, given a choice, commuters will generally prefer to drive cars; second, that the road congestion resulting from this preference can be alleviated by building more roads rather than managing the demand.[11] The inherent geometric inefficiency of single-occupant vehicles as a way to move large volumes of people at peak hour has also been largely ignored.[12]

Melbourne in 1969 was a city of 2.5 million inhabitants. The greater metropolitan area was already vast and dispersed with a predominantly radial public transportation system. Such a system encouraged car usage as a primary means of commuting to work and other daily activities that did not involve movement into or out of the central city. Generally, Melburnians seemed to like the freedom and convenience of cars and there was an openness to freeways as a solution to growing congestion on the existing arterial road network.[13]

The cost of implementing the transportation plan would have been a considerable impost on Victoria’s state finances; however, it was the cost to community amenity and political pressure, particularly in the inner city, that eventually brought changes to the plan’s ambitions. Although spread throughout the metropolitan area, the freeway and arterial road proposals provoked disquiet in inner urban areas where the concentration and density of the freeway network would have caused a major dislocation and reconfiguration of the existing urban fabric. On 19 December 1969, the day after announcing the plan, the Age reported that city councils from Collingwood to Brighton were expressing concerns about a loss of parkland and rateable properties and the permanent disruption to the integrity of many of their neighbourhoods.[14] These initial reactions were the beginnings of the local resistance that led to many of the proposed inner city freeways being deleted from the planning documents.

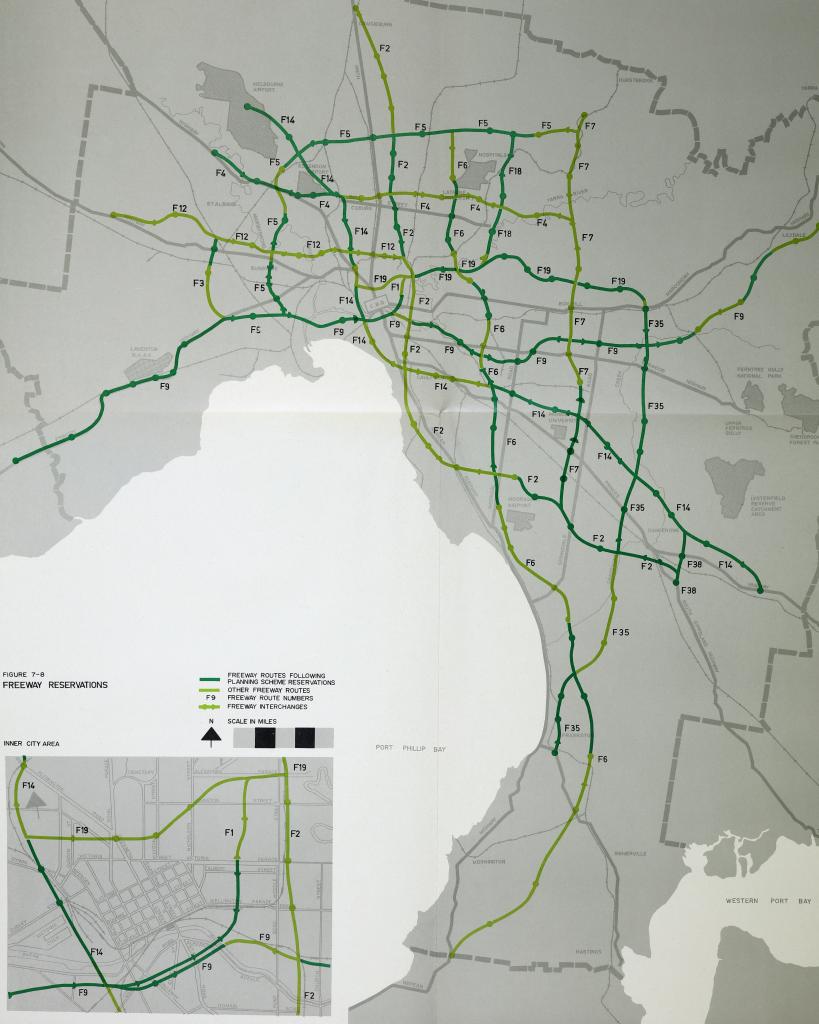

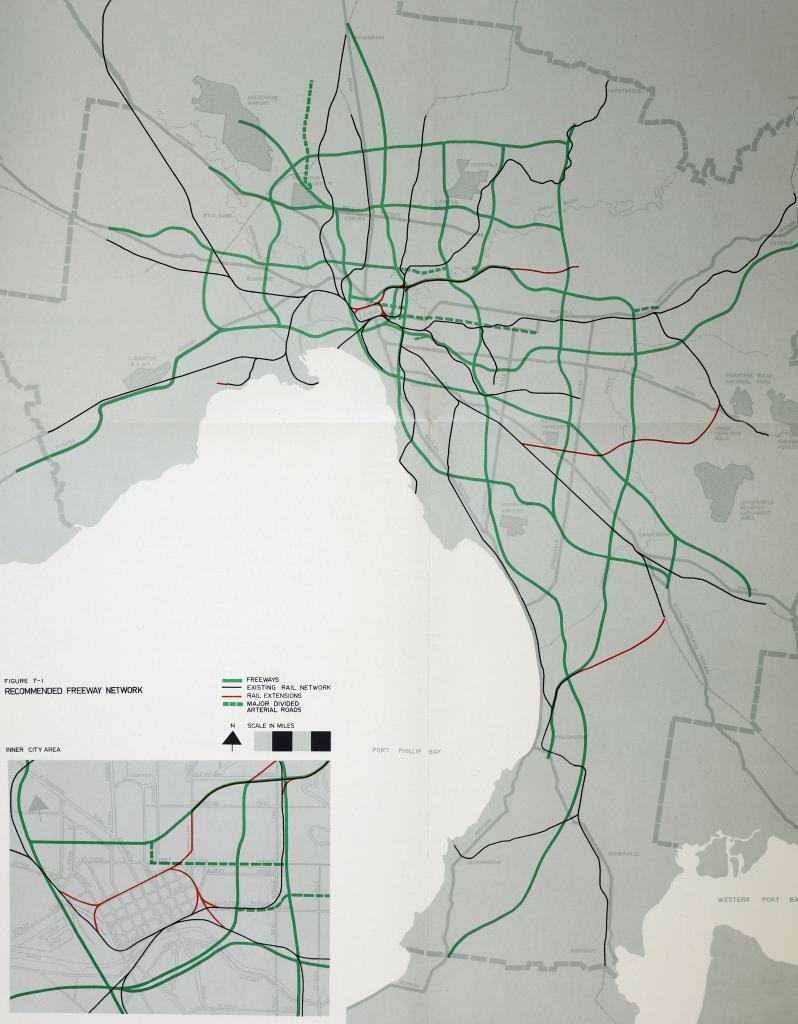

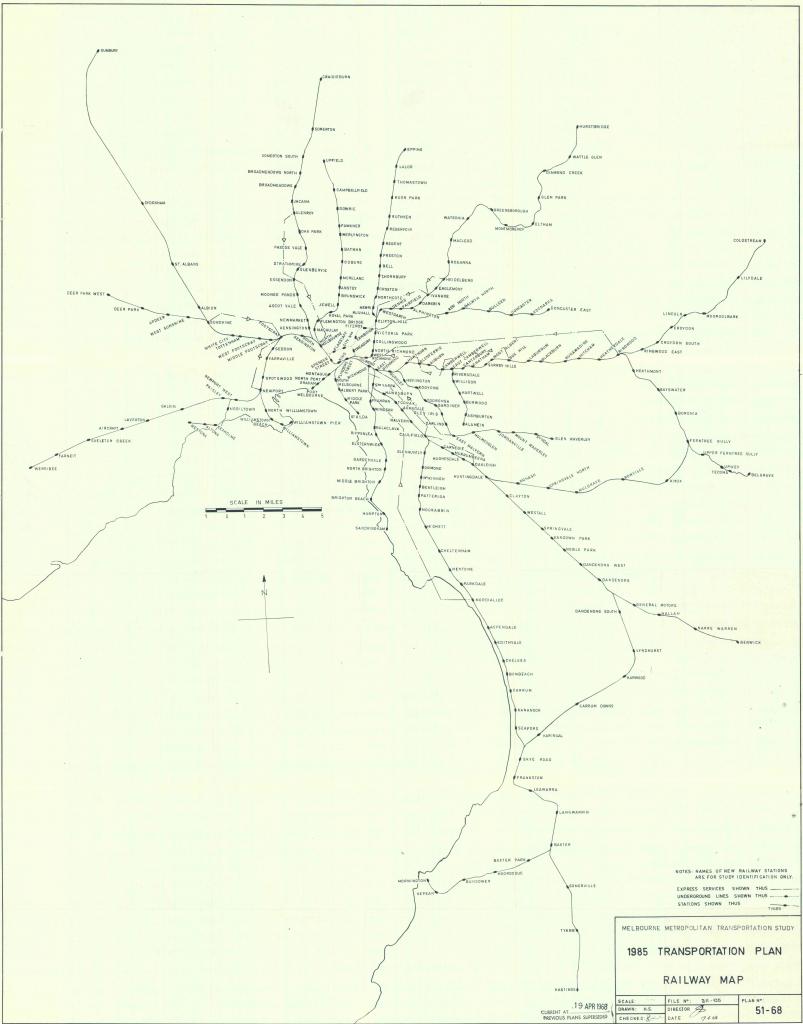

There was much deletion to be done! The 1969 Transportation plan featured 494 kilometres of new freeways integrated with a supporting network of 520 kilometres of highways and arterial roads. This vision would have covered the whole of the Melbourne metropolitan area in a freeway grid that would have resembled aspects of the Los Angeles network.[15] The network was most concentrated in the city’s inner north where many of the new routes would have converged or intersected in relatively dense and well-established suburbs (see Figure 1 for the insets from maps 7-8 and 7-1 from the transport plan).

Among the small number of transport initiatives, the plan proposed an underground rail loop and a new railway line (the Eastern Railway) along what would become the Eastern Freeway (route F19 on map 7-8). At the time the transport plan was made public in 1969, the railway proposal featured a future direct link from the loop via an underground tunnel, including a station at Fitzroy, that would have been partly integrated into a westward extension of the F19 freeway (presumably also underground). A major north–south freeway, the F2 would have intersected with the F19. The proposed route for the F2 (see Figure 1, map 7-8) would have taken it all the way from the Hume Highway at Craigieburn in the north to Dingley, via Merri Creek then through Clifton Hill, Collingwood, Richmond, South Yarra, Prahran and Windsor and other bayside suburbs before heading east to join the Princes Highway.

The integration of the Eastern Railway extension from the loop can be seen in the inset on map 7-1, which also shows major freeway and arterial roads proposed for the area. The prospect of a railway along the freeway was a major selling point in communications surrounding the freeway work; it was touted as ‘Australia’s first road–rail complex, connecting Doncaster and Templestowe with central Melbourne’.[16]

Figure 1: Maps 7-8 (left) and 7-1 (right) from the 1969 Melbourne Transportation plan. The red lines on the right-hand map indicate new railways: in addition to the Doncaster line, a Rowville line connected the Dandenong and Belgrave lines via Mulgrave, and a line connecting Dandenong and Frankston were also proposed. The only rail proposal that actually got built was the city loop.

These were the proposals in the published report, but there were several draft versions of the freeway and rail proposals that emerged in the Melbourne transportation study that preceded the final report. The study was largely shaped by policy networks that were heavily skewed towards freeway building that gave the published plan its supporting evidence and justification.

The Melbourne transportation study

The 1969 plan followed many years of data gathering (including surveys and interviews) and analysis that started in 1963. The study was designed to inform decision-making by the Melbourne Transportation Committee, which had representatives from ‘all authorities concerned with transport, road building and planning’. The work was conducted by the firm Wilbur Smith & Associates from the USA, with the support of LT Frazer and Associates in Melbourne. Wilbur Smith was widely known to be a freeway advocate, and his firm’s appointment clearly signalled a preference to find a freeway solution rather than a transport plan that gave due consideration to public transport options.[17] With the aid of computer analysis, the study extrapolated from data collected in the mid-1960s to model what would be needed from Melbourne’s transport infrastructure by the year 1985.[18]

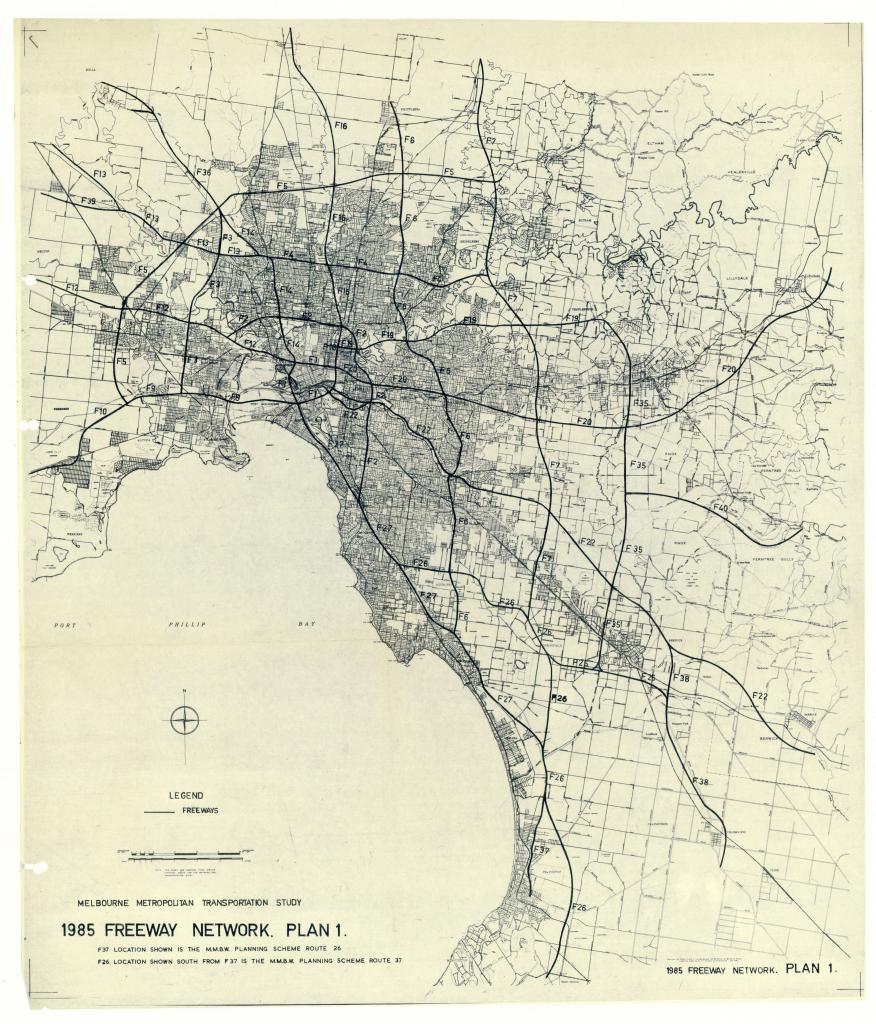

The draft freeway and railway networks that emerged from this research and analysis show an evolution that led to the proposals put forward in the 1969 plan. These documents are now held by Public Record Office Victoria (PROV). The freeway route numbers and the physical location of routes changed with each draft as analysts and engineers worked out what was considered to be an optimal coverage for the entire metropolitan area. These abstract lines on a map could be shifted at will and seemed to pay scant attention to the neighbourhoods they would impact; seemingly, the thinking was that, if the modelling and engineering deemed it was required, the impacted residents would simply have to accept the necessity for progress. The development of the published plans (described above) occurred through an iterative process using computer modelling:

Seven possible plans were developed and tested before the final plan, now recommended, was evolved. Each of these plans took between 30 and 45 weeks’ work for a full-time staff of 13, including six professional engineers and two economists. This time was taken up in planning network layouts, preparing computer input data, displaying and interpreting the computer output and evaluating performance characteristics of the networks. Actual computer operation took about ten hours per plan.

The findings of the testing process were reported to the technical committee which in return reported their recommendations to the full committee which made the final decisions.[19]

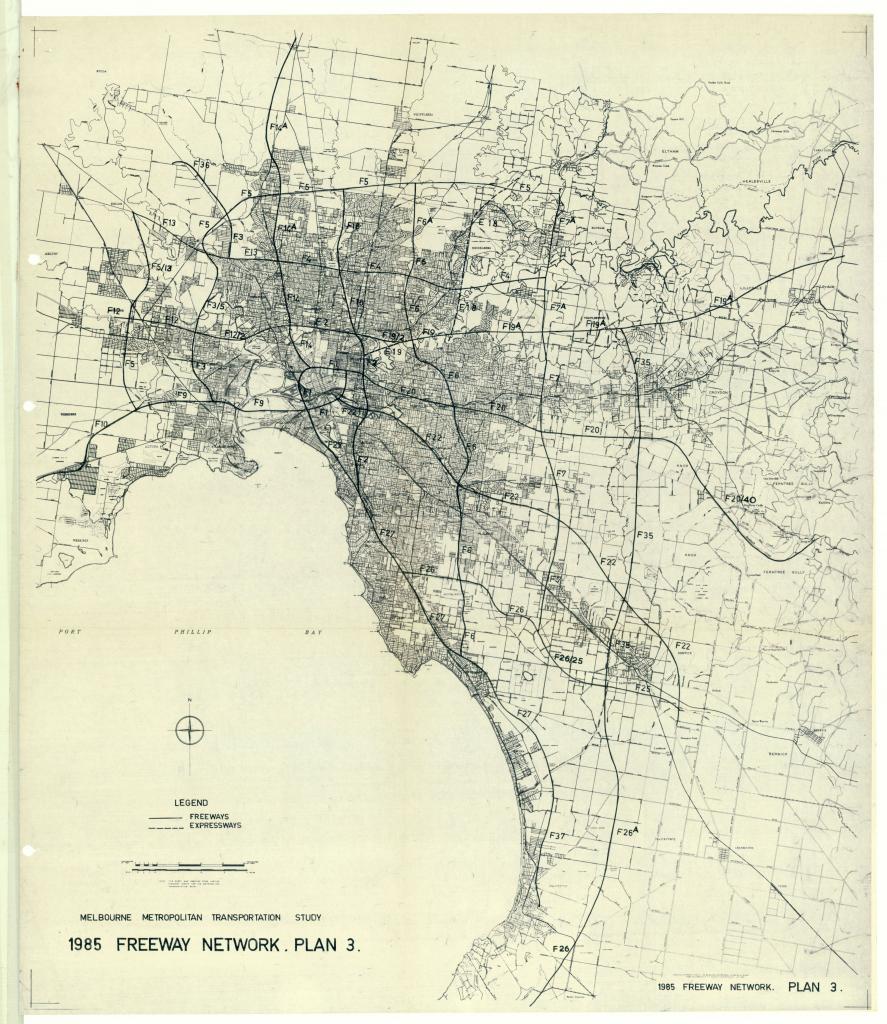

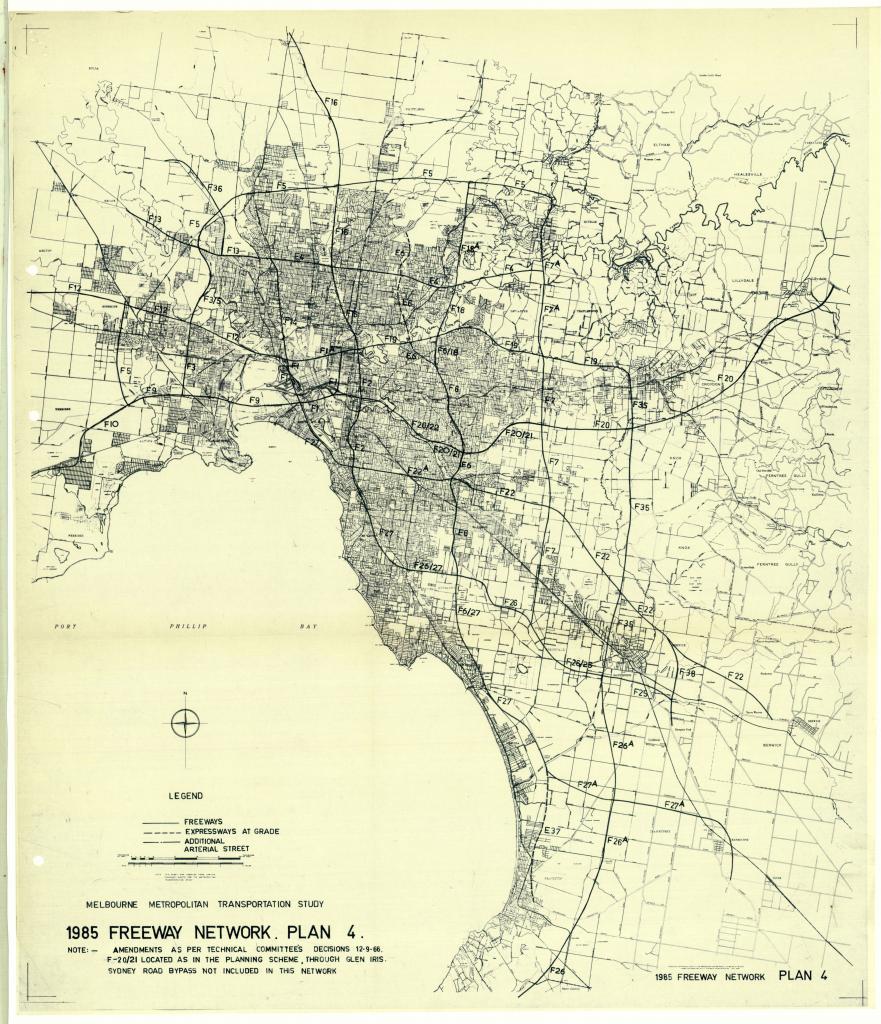

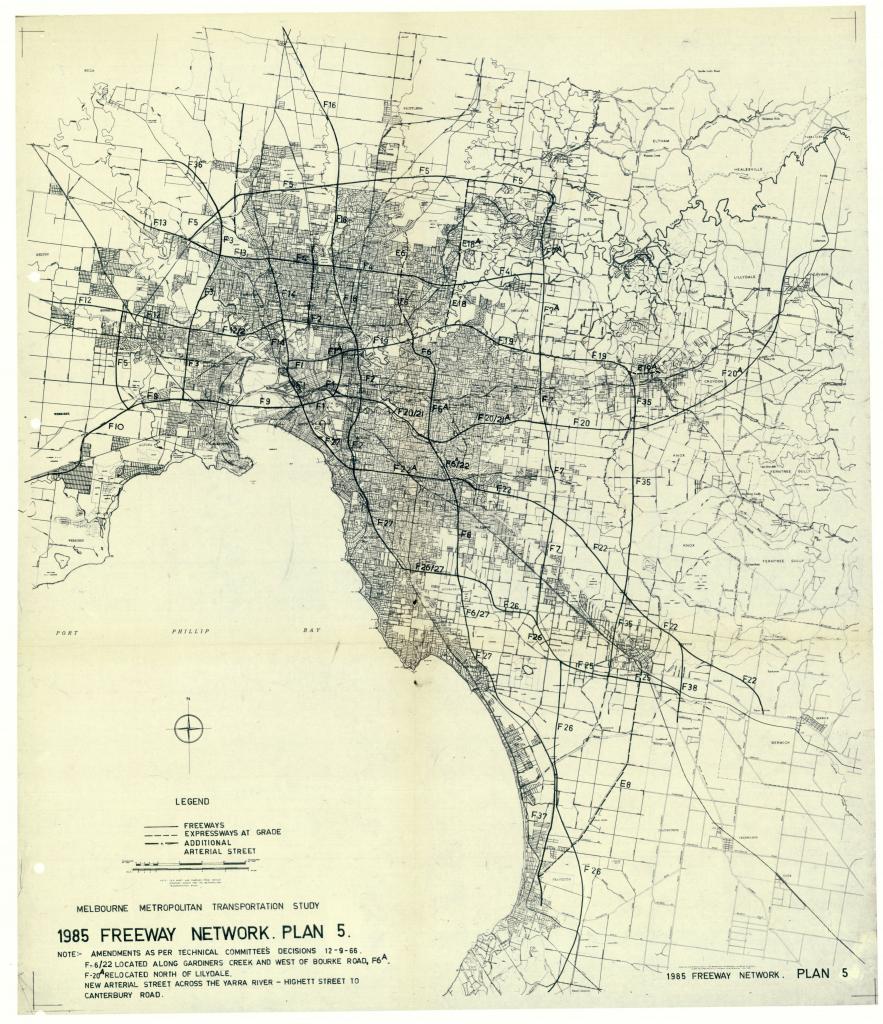

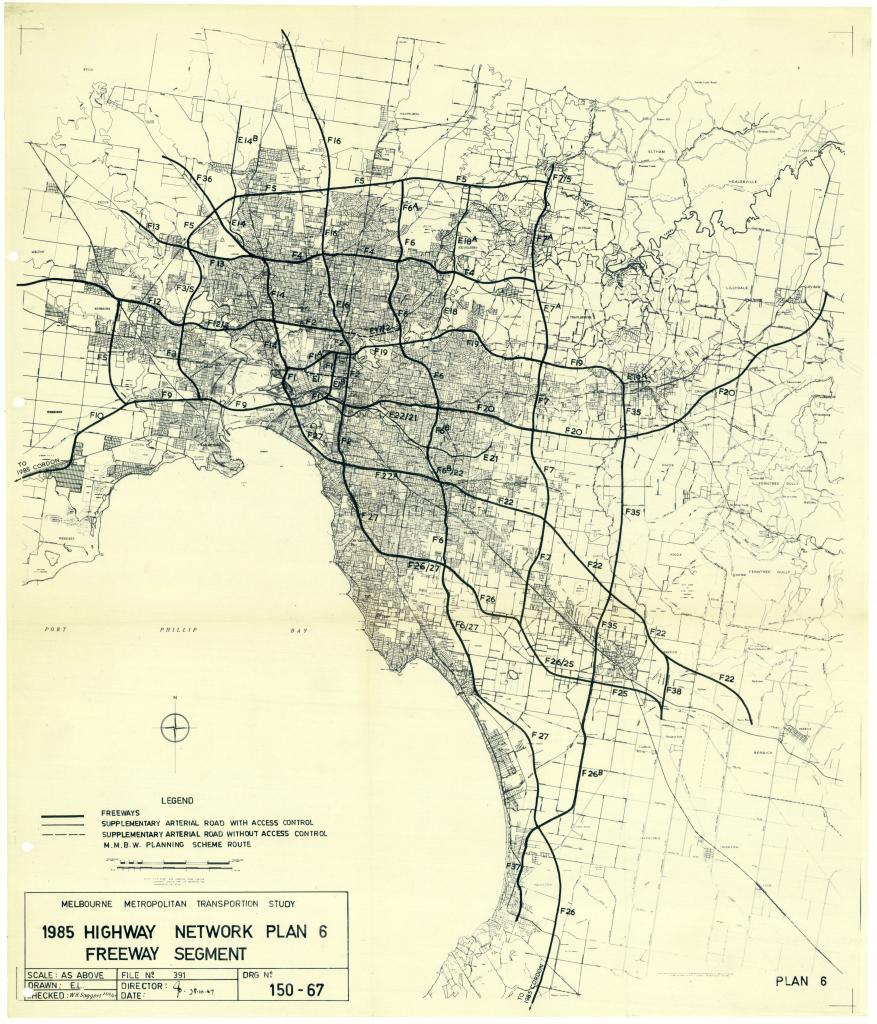

Six of these seven plans are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Lines on a map: the evolving freeway network. Starting from top right, plans 1, 3, 4, 5 and directly above plan 6. Compare these to Figure 1 (the published 1969 plan). PROV, VPRS 10090/P1, Unit 19, Melbourne Transportation Study. Click on the images to view details in enlarged versions.

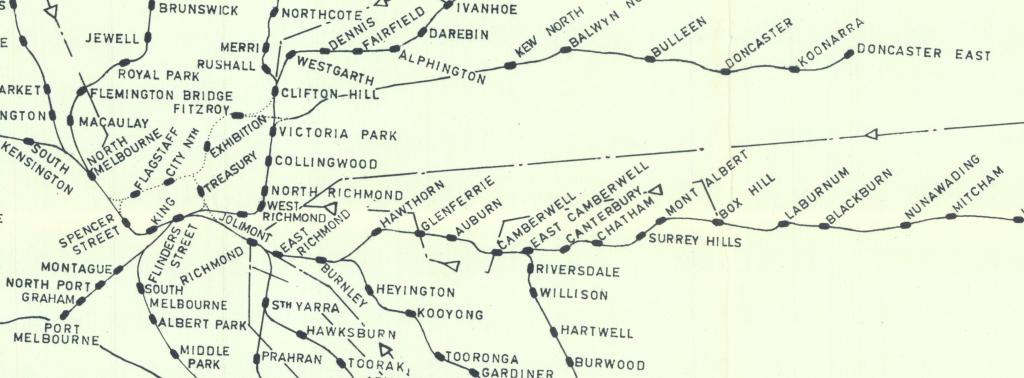

In one of the draft railway plans, the underground loop extension for the Eastern Railway featured not only a station at Fitzroy but also one named Exhibition (named for its proximity to the Exhibition Building), and a station named King on the southern part of the loop (presumably above King’s Way on a viaduct) (see the inset in Figure 3). These proposed stations were not included in the published 1969 plan.[20]

The underground loop was among the early projects to get underway, commencing shortly after the release of the 1969 plan. The Melbourne Underground Rail Loop Authority (MURLA) began operating on 1 January 1971, just a little over a year after the release of the 1969 plan. Shortly thereafter, as work commenced on planning the alignment of the actual tunnels, and as the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) began work on the Eastern Freeway, the idea of a tunnel directly from the loop through Fitzroy to the freeway (where it would run in a median strip to Doncaster) came under question.

Figure 3: Draft railway network plan, 17 April 1968, from records of the Department of Transport documenting the evolution of the transport study, PROV, VPRS 10090/P1 Correspondence Files, Unit 18, File 394-F 1985 Transportation Plan – Rail services Melbourne and metropolitan transport study. The full plan (top) and a detail (bottom) showing the proposed new stations on the loop (King, Flagstaff, City Nth, Treasury) and the Eastern Railway (Exhibition, Fitzroy, Kew North through to Doncaster East). Also proposed was a Rowville line connecting the Dandenong and Belgrave lines, and a new line connecting Dandenong to Frankston. Only the loop was ever built.

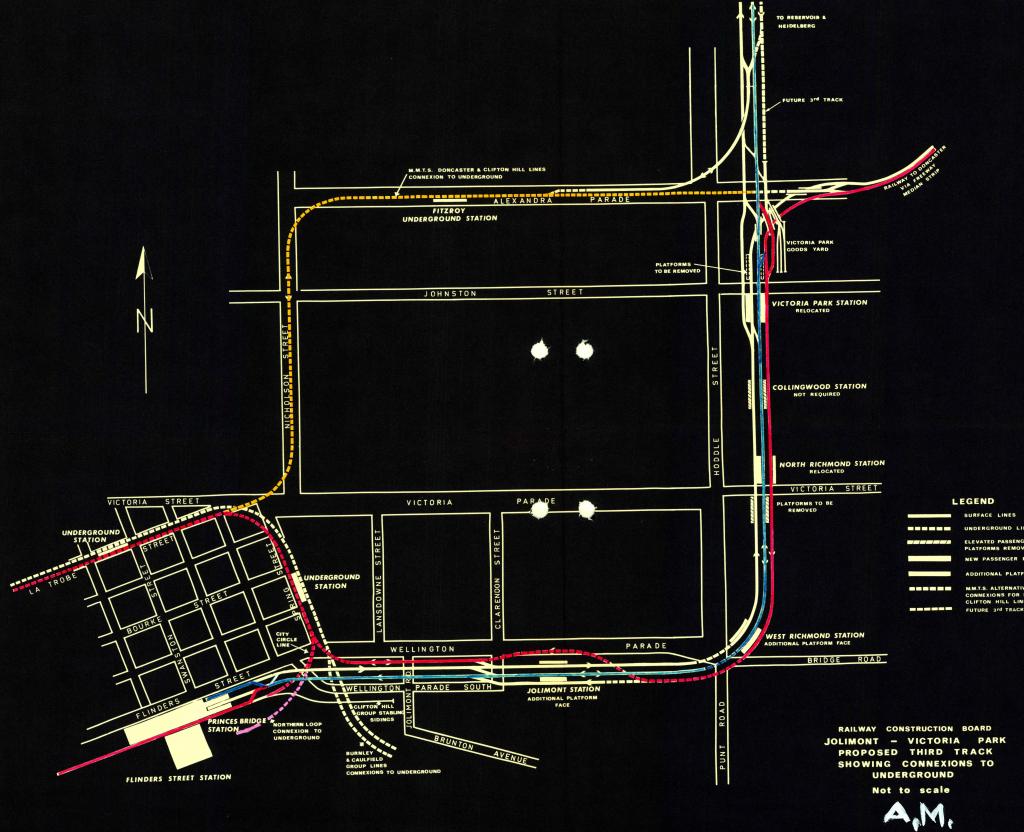

Writing to Director of Transport GJ Meech in August 1972, MURLA Acting Chief Engineer GG Bennett sought clarification on whether planning work should continue to accommodate a future Fitzroy tunnel. The letter questioned the need for the tunnel, the extra costs and engineering considerations involved and sought direction as to whether its future connection to the loop should be considered in designing the main loop tunnels.[21] Though immediately raised with then Minister for Transport Vernon Wilcox in a memorandum dated 23 August 1972, a final decision was not made until 1975 by his successor ER Meagher who ‘accepted the recommendation that the junction and associated works be deleted’.[22] This meant that the underground loop tunnels would be built in a way that would foreclose forever the possibility of the Fitzroy tunnel being added at some future date (the proposed alignment for the Fitzroy tunnel is shown in yellow in Figure 4). This proved to be a harbinger of what was to come for the Eastern Railway, which remains unbuilt despite the reservation created on the freeway to accommodate it, and numerous studies and promises to build it.[23] By the time the Fitzroy rail tunnel was formally abandoned, many of the freeway routes, particularly in the inner city, had already been ‘deleted’, not primarily because of financial costs or engineering difficulties, but because people did not want them in their neighbourhoods. As we shall see, abstract lines on a map had disruptive consequences for real communities that rejected the characterisation of their suburbs as slums requiring urban regeneration, and which saw themselves as already undergoing renewal and regeneration on their own terms.[24]

Figure 4: The first part of the Eastern Railway that was formally dropped: the tunnel connecting it to the underground loop beneath La Trobe Street in the city to the Eastern Freeway (dotted yellow line), PROV, VPRS 6347/P4 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number, Unit 125, File 76/236.

City ring-road—the first freeway deletion

The first indication that the freeway plan would meet fierce community resistance followed an attempt to commence work on the eastern leg of an inner city ring-road. In what would be unimaginable today, a major freeway and extensive access ramps were proposed that would cut through some of Melbourne’s most iconic parks (namely, Fitzroy Gardens, Yarra Park and the King’s Domain) and bisect one of its inner suburbs, East Melbourne (see Figure 7 for a model to visualise the full extent).

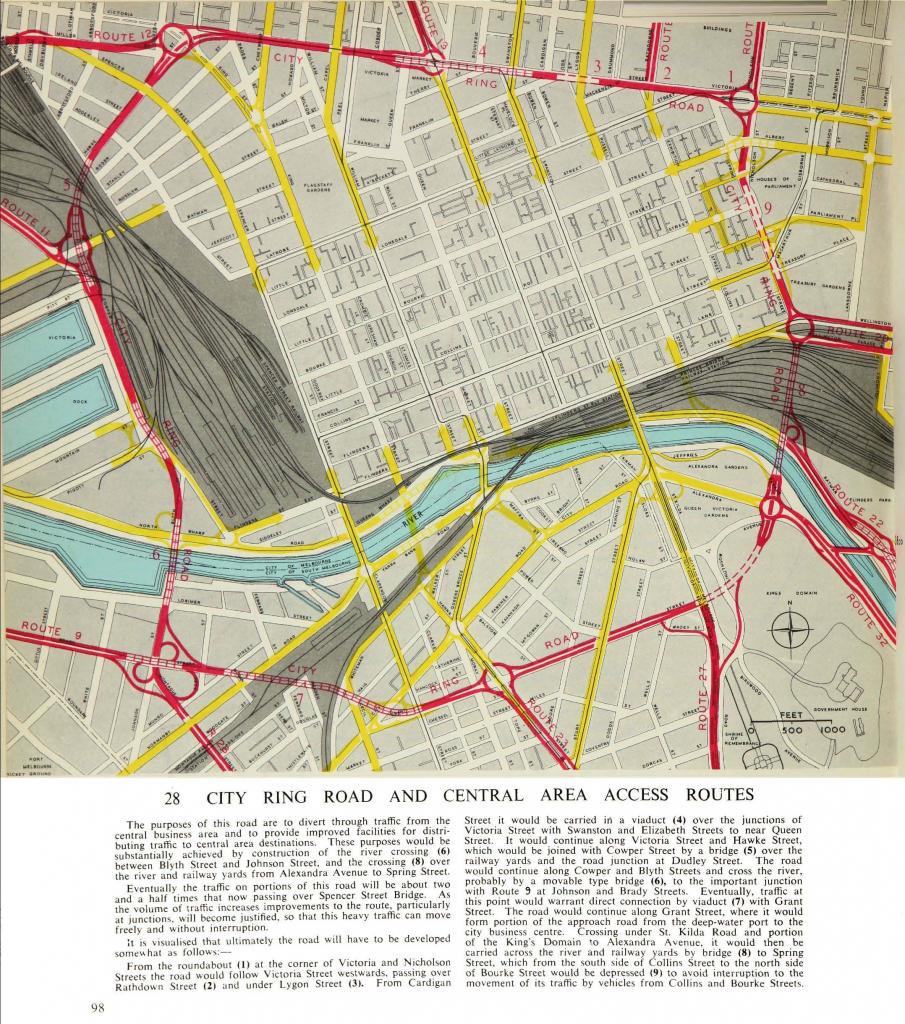

The idea for an inner city ring-road in Melbourne was first officially proposed by the MMBW in the Melbourne metropolitan planning scheme 1954 report. The road was intended to alleviate through traffic using the city centre to reach destinations beyond. In the initial proposal, the eastern leg of the road was to be partially underground in a trench along Spring Street in front of the Victorian Parliament, and would cross over the Jolimont Railyards and the Yarra River via a bridge to reach Alexandra Avenue. From there it would have tunnelled under King’s Domain to connect up with Grant Street in South Melbourne.

Figure 5: MMBW, ‘City ring road and central area access routes’, Melbourne metropolitan planning scheme 1954 report, p. 98. This was the first time a city ring-road was mooted as a solution to CBD traffic congestion. In this version, the eastern leg of the road would have been in a cut and cover trench along Spring Street in front of the Victorian Parliament and a proposed Civic Centre that would have been built opposite it.

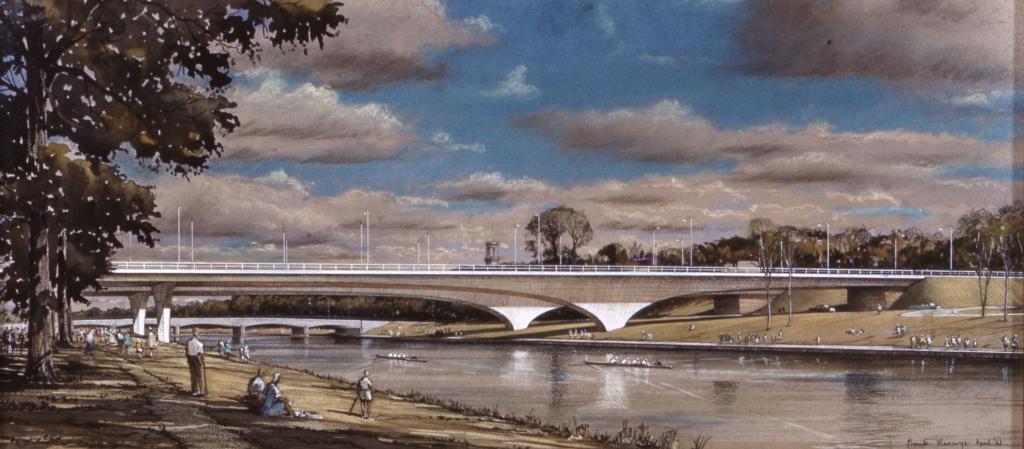

The MMBW approved the road in 1963, but relocated it eastward to Clarendon Street in East Melbourne. A ramp alongside the southern end of the Fitzroy Gardens and Wellington Parade would have elevated the road to cross the Jolimont Railyards and the Yarra via a bridge (see Figure 6). The encroachment on parkland and amenities precipitated protest from local communities and sections of the media.[25] In defending their selection, the MMBW explained that Spring and Landsdowne streets had also been considered but, for a variety of reasons including costs, aesthetics, encroachment on parkland and engineering difficulties, the Clarendon Street alignment had been chosen as the best option.[26] By 1965, opposition to the road was enough for the Bolte government to let the project go into abeyance and request alternatives. However, in July 1967, the Victorian Government, acting on advice that this remained a high priority project, gave Cabinet approval to the ring-road and three other major road projects advanced by the MMBW.[27] Despite community unease, the road was also included as a priority project in the Melbourne Transportation Committee’s 1969 transportation report (see Figure 1, F1 route in map 7-8). As Dingle and Rasmussen have explained, the network of inner city freeways depicted as ‘lines on the map were on too small a scale for detailed appreciation of their impact’.[28]

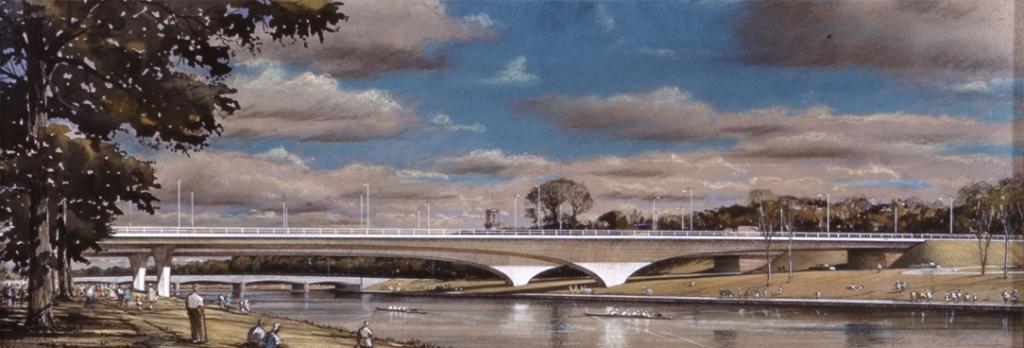

Figure 6: Detail of a photographic slide taken of a framed artist impression of the Yarra bridge for the eastern ring-road, which roughly coincides with the location of the current underground CityLink tunnels. This view of the bridge’s elegant span is from the Jolimont side looking eastward, the Swan Street bridge can be seen in the background, PROV, VPRS 8609/P37, Unit 60, F MISC.

Figure 7: Detail of a photographic slide featuring a model of the eastern ring-road, showing its proximity to parklands, the Myer Music Bowl (see on the left), the MCG, and a variety of associated approach roads and ramps along Wellington Parade and the area now occupied by the tennis centre, PROV, VPRS 8609/P37, Unit 60, F MISC.

Among the MMBW records held by PROV are scrapbooks containing newspaper clippings in VPRS 8609 Historical Records Collection. There is an entire scrapbook devoted to newspaper clippings about the city ring-road, indicating officers of the agency were closely following the public reporting on a project that the agency was strongly advocating. The reports were largely taken from the Sun and Herald newspapers between 1969 and 1971 and provide a rolling narrative of the saga behind the construction of the city ring-road. The East Melbourne Group, a community organisation opposing the road, the Urban Action Committee (composed of numerous councils whose suburbs would be affected by the road) and the Town and Country Planning Association emerged as the main antagonists, highlighting impacts on communities and loss of parklands. A refusal to explore alternatives after the issue first came to a head in 1965, such as putting the road under Clarendon Street, emerged as areas of contention. As opposition to the road grew, public statements from Minister for Local Government Rupert Hamer and Premier Henry Bolte indicated that they too were starting to doubt the necessity for the road.[29]

The eastern leg of the city ring-road was the first piece of the visionary 1969 plan to be officially renounced by the government. Concerted community and media scrutiny led Cabinet to drop the road in October 1971 after the MMBW was unable to provide viable alternative options. The MMBW had ‘full contract drawings and was ready to call tenders’, but the plans were defeated by a revaluation of the inner city’s existing urban fabric, showing that:

Melburnians in the 1970s had a different set of values from the 1950s and different expectations of planning. Planners increasingly needed to combine their technical expertise with a consideration of intangible, unquantifiable values such as aesthetics, sense of community and attachment if their plans were to be implemented.[30]

The eastern leg of the inner ring-road was formally scrapped on 4 October 1971 with the Victorian Government announcing that it would be looking towards public transport options to ease traffic congestion in the inner city. In addition, the government stated it would order the Melbourne Transportation Committee to review the 1969 plan and would consider modifying it ‘to reduce costs and disruption of community life’.[31]

Community opposition to the F2

As we have seen, the inner city ring-road was the first casualty of the ambitious freeway plan to be abandoned. The reason for this was community opposition to the impact it would have had on an inner suburb (East Melbourne) and adjoining parklands. Meanwhile, one of the very few railway proposals (an underground tunnel under Fitzroy) had been formally abandoned, placing in doubt the Eastern Railway because it was meant to service the increased peak hour traffic from that new line. This was done primarily because of cost and engineering difficulties, and indicated that, when it came to public transport, the government had little appetite to fund anything but the bare minimum compared to the vast sums involved in constructing the proposed freeway grid.

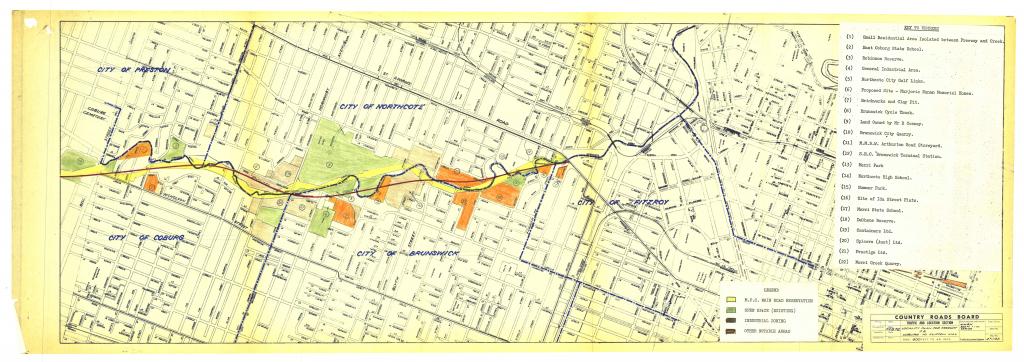

The community backlash that commenced with the inner ring-road proposal soon spread to other suburbs facing disruption by freeway building. Among the many records held by PROV that relate to the F2 freeway and freeways in general are three large Ministry of Transport correspondence files. Each of them contains hundreds of letters and associated documents (for example, reports, plans and newspaper cuttings) on the F2 freeway proposal. These files provide detailed evidence for how disruptive this freeway would have been, not only disturbing the Merri Creek valley as a place for recreation and enjoyment of open space, but also impinging on numerous facilities and community structures along its path, including the Merri Creek Primary School (see Figure 8). They also document the concern of residents south of Merri Creek in Fitzroy, Clifton Hill, Carlton and Collingwood that would have had the F2 and other freeways bisecting their residential areas. The files show how public servants and their respective ministers considered the project’s impacts on stakeholders, particularly local residents and communities, and local government bodies. Some of the documents reveal the sensitivity of ministers and public servants as to how announcements about the project would be perceived, and how they attempted to manage these outcomes.

Between 1971 and 1979 many letters were written to ministers for transport and local government from members of the general public, protest and local community groups, local councils, members of parliament and a range of other interested parties in relation to the F2 freeway. Many express one or several recurring concerns: the diminishment of local amenities if freeways and arterial road upgrades were to be built; the increase in traffic a major route would induce in the surrounding suburbs; and uncertainty about private property, namely whether homes would be compulsorily acquired and whether there would be a negative impact on property values adjacent to those acquired for demolition.

The correspondence demonstrates the constant pressure that can be exerted on a government by the simple act of letter writing and relentlessly asking informed and pointed questions. It also reveals tensions between the politicians heading various ministries, the various ministers for transport, local government and planning, and the senior officials running the Country Roads Board (CRB) and the MMBW, whose agencies were empowered to set their own independent agendas. With the F2 being effectively an extension of a state highway (the Hume), the CRB was undertaking the project and the correspondence sometimes reveals a reticence to acknowledge and respond to the political expediencies that were paramount for an elected government.[32] The CRB continued to see the route as essential. As one of two major north–south freeway routes, the F2 was considered a crucial piece of the overall network’s design. The central part of the route would have cut through long-established industrial and residential neighbourhoods, areas that planning authorities had long thought required urban renewal and could, therefore, be amenable to freeway incursions without considering the consequences for those concerned. This was a miscalculation that misunderstood the renewal that was already underway through the influx of migrants and, more recently, the arrival of young professionals and others with a willingness to organise and resist.[33]

The original idea for the F2 was for a cross-city freeway (effectively from Cragieburn to Dandenong through the middle of the city); however, local community opposition emerged most strongly in the northern suburbs, no doubt because the February 1971 press release from Rupert Hamer (then minister for local government) announced that work would begin with an investigation of the route along Merri Creek from Bell Street to Clifton Hill, where land had already been reserved for an arterial road in the existing metropolitan planning scheme.[34] The proposed route would have snaked its way along the creek from the north where the road would connect with the Hume Highway in Craigieburn, until it reached Clifton Hill, at which point it was to somehow intersect with the Eastern Freeway or Alexandra Parade. Merri Creek was the border between several suburbs and municipalities and numerous community facilities had been established on its banks, in particular, a number of parks and recreation reserves, a velodrome, government schools and retirement villages. In addition, parts of residential areas near the creek along what emerged as the CRB’s preferred route would have to be demolished or would become ‘islands’ between the freeway and the creek. For these reasons, a sociological study of the likely effects on residents was commissioned.[35]

The existing planning scheme provision for a road along the creek was considered to be too narrow and curvy for a modern freeway and, consequently, incursions into surrounding residential areas and other facilities became a likelihood if the CRB’s preferred route was adopted. Among the first properties identified as requiring acquisition by the investigation were 40 new residential flats under construction in Ida Street, Fitzroy North.[36] The need to cease construction of the flats, compensation for the developers and purchase of the land was reported in the Age on 22 February 1972.[37] The flats are shown on a plan indicating residential areas, infrastructure, facilities and existing structures that would be impacted by the proposed route (see Figure 8). The minister for local government was provided with briefing notes on the freeway proposal, which stated that the CRB ‘would have no objection to the Minister showing this plan to the T.V. cameras but requests that it not be made available to the press until the plan has been forwarded to councils and other authorities concerned’. Interestingly, handwritten annotations by Chairman of the CRB REV Donaldson added the observation that ‘it could be wiser NOT to show the plan even to the TV cameras’.[38]

Figure 8: Country Roads Board, locality plan for freeway F2 Coburg to Clifton Hill, dated February 1972, showing the existing road reservation as a yellow strip, the board’s preferred route as a red line, and the various community, residential and infrastructure sites affected by the preferred route in various shadings with a corresponding list, PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part 1.

Anticipating that traffic from the freeway would have flowed into and out of (via on/off ramps) main roads on either side, concerns were raised by Preston, Coburg, Northcote, Brunswick, Clifton Hill, Fitzroy, Collingwood and Melbourne councils. From the outset, these councils, which formed the F2 Regional Municipal Committee, felt that they were not being properly consulted by the CRB and that the agency was not responding to their requests for information.[39] Media reports appeared indicating decisions were being made without community consultation. The correspondence received by the minister for transport shows that, in March and April 1972, councils were not the only parties seeking further information and assurances, or expressing a wish to be consulted. For instance, the Pensioner’s Association of Victoria requested assurances that the Marjorie Nunan Memorial Homes in Brunswick East would not be affected by the road; Chairman of the East Brunswick Freeway Protest Association ML Ayles sought a meeting to discuss worrying claims appearing in newspapers; Member for Brunswick East David Bornstein requested an opportunity to meet with senior officers of CRB to become fully informed; and Member of the Legislative Assembly for Northcote Frank Wilkes wanted information, as the road affected his electorate.[40]

The correspondence also shows community organisations started to organise and meet to garner opposition to the project. For instance, the East Brunswick Progress Association wrote to Local Government Minister Alan Hunt to express their opposition to the F2 freeway; report that, at their April 1972 meeting, ‘some 90 members and residents living adjacent to the proposed Hume F2 Freeway [recorded their] total opposition to this plan to further decimate our city with yet another freeway’ (a reference to the Tullamarine Freeway on Brunswick’s west boundary); and stress the need for better public transport instead.[41]

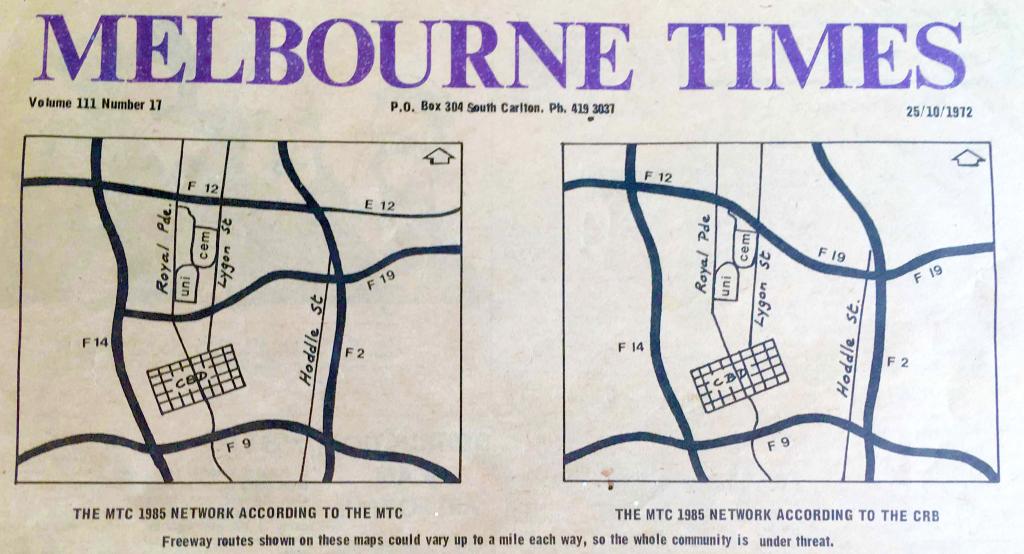

Under the leadership of newly appointed Premier Rupert Hamer, the Victorian Government’s position on freeway construction continued to soften. By the end of 1972, it had publicly acknowledged the need to avoid disrupting established inner urban residential areas and communities.[42] This intention, however, was difficult to square with the CRB’s continuing push to seek alternative freeway routes through inner suburbs. In October, the Melbourne Times published a map showing how the CRB was proposing to accommodate not only the F2 but also an extension of the Eastern Freeway through Carlton North (Figures 9 and 10).[43]

Figure 9: Report on the CRB’s plan for an extension of the Eastern Freeway (F19) through Carlton North, ‘CRB stakes its claim to North Carlton’, Melbourne Times, 25 October 1972, p. 1.

The Carlton Association (CA) was one of the most vocal and well-organised groups that opposed not just the F2 freeway, but also questioned the imposition of freeways on the inner urban fabric without due consultation and proper coordination. The association benefited from the young, educated professionals that made up its membership, and proved to be influential and effective in shaping a range of inner city urban policies apart from freeway issues, including ‘slum clearances’ for high-rise flat development proposed by the Housing Commission of Victoria (HCV), local traffic management and other local planning issues.

The members of the CA were part of the demographic transformation that swept through Melbourne’s inner north in the 1960s and 1970s, their presence coinciding with the decline in manufacturing and working-class jobs in those areas.[44] Many newcomers were attracted by the affordable and conveniently located housing close to places of work or study, the nineteenth-century urban fabric of the inner city and the cosmopolitan conviviality of the new European immigrant communities that were already established in those places. Their activism drew inspiration from influential overseas thinkers, such as Jane Jacobs who had participated in, and written about, organised community resistance against similar threats in lower Manhattan.[45] Howe, Nichols and Davison have described the demographic groupings (often overlapping or merging) in inner Melbourne as consisting of ‘patricians’, ‘trendies’ and ‘radicals’.[46] Together they formed a broad and diverse inner city coalition of activism that sought to defend their neighbourhoods from ‘bureaucratic silos, unresponsive to democratic influences … predominantly staffed by men with a technical background, many of them returned servicemen’. Howe, Nichols and Davison characterise the clash as being:

Grounded in the cultural divide between old-fashioned, hard-nosed technocrats and a younger generation of university-educated professionals attuned to ideals of personal self-discovery and democratic decision-making. The inner suburbs became their battlefield … neither the HCV nor CRB had adequate capacity for economic and social impact planning.[47]

The CA, and allied groups, effectively provided the environmental and social impact assessments, and often were able to produce cogent and informed alternative planning proposals drawing on the relevant expertise of the many academics in their memberships. As it turned out, they often found it far easier to engage with ministers and the premier than with the men of the planning authorities.[48]

The CA included specific action groups formed for particular purposes. A Freeway Action Group was formed on 23 December 1971 convened by John Anderson. The aims of the group were to halt freeway construction in the inner suburbs until all viable alternatives were explored by the relevant authorities and the public was given an opportunity to debate these, to liaise with relevant authorities involved in freeway planning and construction, and to forge links with other community groups taking similar action to share information. A newsletter produced by the group in February 1972 stated that block organisers were ‘being appointed to deal with distribution of leaflets, petitioning, door-knock appeals etc’, and called for more volunteers to undertake these tasks. The newsletter also reported that consultations were being planned with the MMBW, CRB, Metropolitan Transportation Committee and planning consultants.[49]

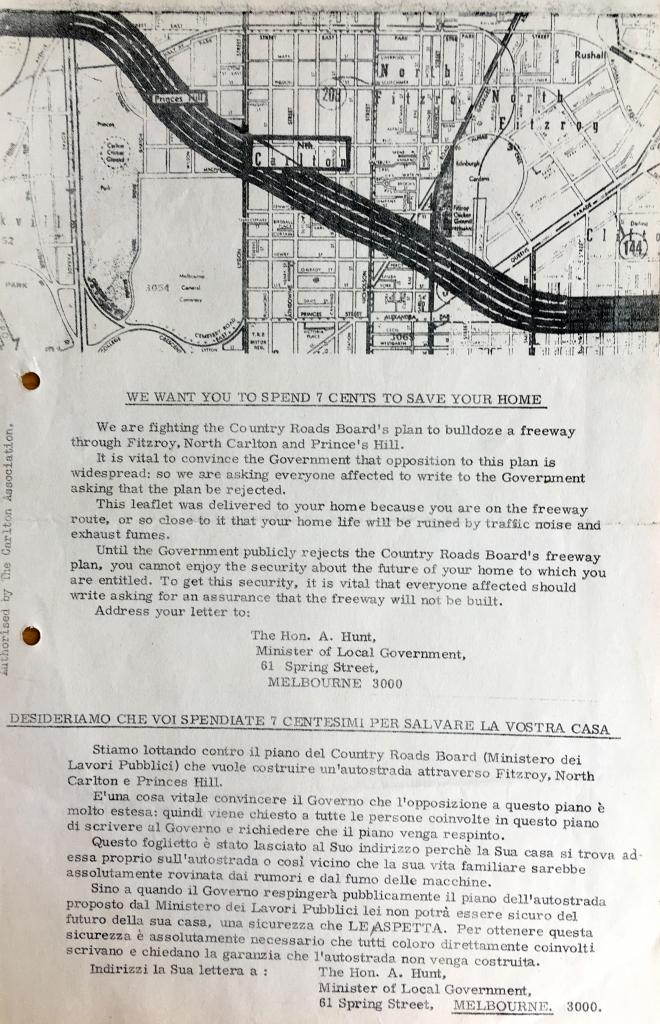

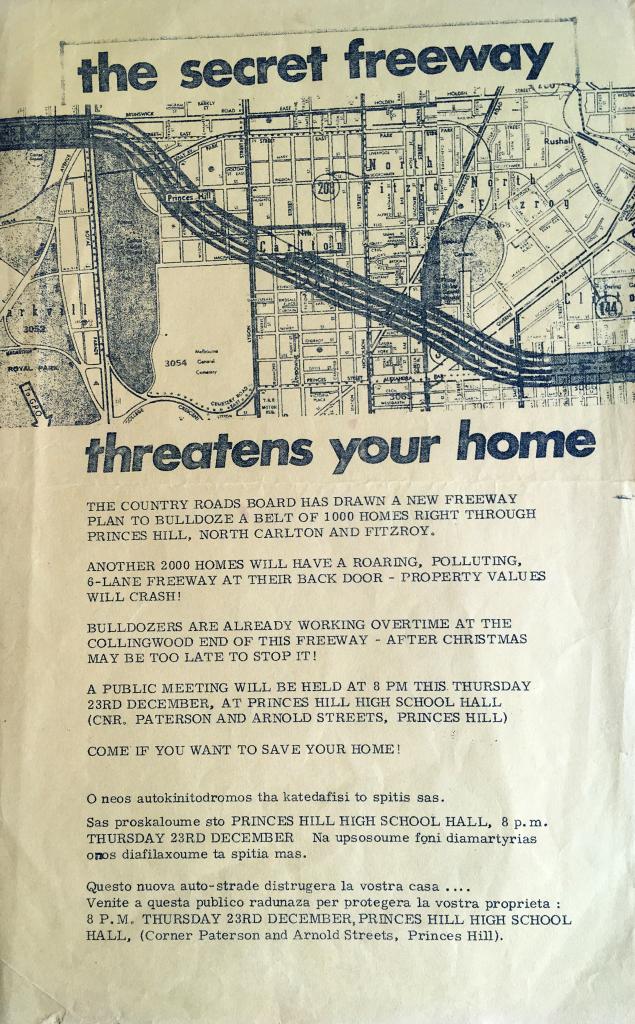

A dramatic flyer to encourage letter writing shows the proposed freeway slashing through Carlton North with information translated into Italian.[50] The CA was cognisant of the large Greek and Italian communities living and working in the area and sought to inform and mobilise them as part of letter-writing and other campaigns by appointing liaisons with native language skills and printing translations of relevant information (Figure 10). One such volunteer, Aurora Calogero (who was among the members present at the group’s inaugural meeting), reported on her engagements with Italians running businesses in the Carlton area.[51]

Figure 10: Carlton Association leaflets with Italian and Greek translations, depicting the extension of the Eastern Freeway through Fitzroy North and Carlton North to Brunswick South, University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092, Unit 5, files 4/5/4 and 4/5/5.

In its March 1973 report, Freeway crisis, which was also endorsed by the executive of the Fitzroy Residents’ Association, the CA Freeway Action Group highlighted the inequity associated with the social costs of freeway building, arguing that:

The social cost component has received inadequate consideration to date. Typically, those likely to benefit most from a new freeway are the already affluent, who own one or more cars and make full use of them; the freeway serves these people at the expense of the few (frequently the underprivileged) who have to bear the social cost component.[52]

A deputation from the association met with Minister for Local Government AJ Hunt on 3 February 1972 and received his assurance that the stated Victorian Government policy on freeway planning would oblige the freeway building authorities to accept ‘the need for priority to be given to environmental and social factors above cost and engineering factors’.[53] However, the report observed that there was little evidence that this policy was being followed by either the MMBW or CRB. Among the other points raised in the report was the lack of coordination between the two freeway building authorities on matters such as the junction of the Eastern Freeway terminus in Collingwood (then under construction by the MMBW) and the proposed F2 (under planning by the CRB). The report also drew attention to the CRB’s ‘secret plan’ for an extension to the Eastern Freeway that would cut diagonally across Fitzroy North and Carlton to Brunswick South.[54]

The association had links with a number of other local protest and community groups in Melbourne’s inner north. Among these were umbrella groups such as the United Melbourne Freeway Action Group with more than 20 representatives from various community groups and individuals, primarily from the inner northern, eastern and southern suburbs. Consequently, the CA’s records allow us to glimpse not only their side of the anti-freeway fight, but also that of other community organisations with which they collaborated.

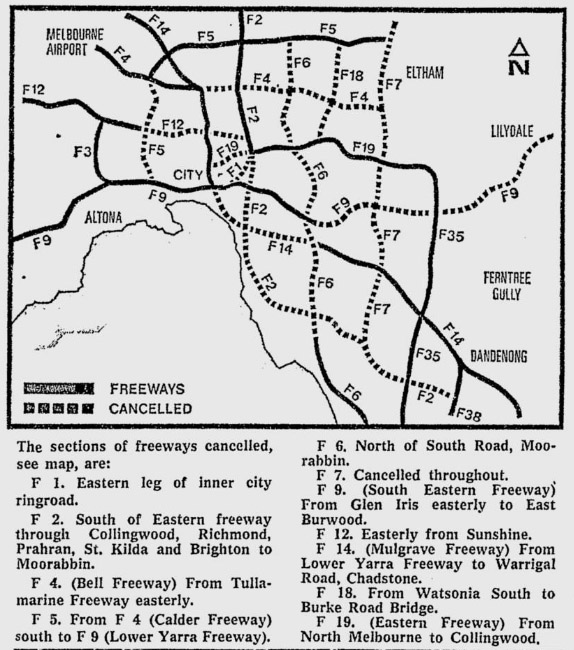

Responding to community concerns and fear of electoral backlash

On 28 March 1973, with a state election looming, the Victorian Government announced that it would effectively halve the number of freeways planned for the Melbourne metropolitan area. Those in outer suburbs and country areas would be built, but the premier cited ‘sociological and environmental impact’ as reason to abandon the inner city proposals. Many of the inner city components of the plan were indeed deleted from future plans; however, the F2 from the Eastern Freeway to Craigieburn had survived for the time being (as shown on the map in Figure 11 below). The premier observed that the deletions would curtail the ‘freedom of movement’ originally envisaged by the freeway grid and that alternatives, such as tunnels and airspace over railways, might still be investigated to allow traffic to bypass the central area.[55] As an Age editorial opined on 30 March 1973, ‘when a network of freeways is superimposed on an old-established and fully developed city, the disruption and damage to residential neighborhoods, to parks and gardens, to the whole environment and the community structure may far outweigh the benefits of easier transportation’.[56]

Figure 11: Detail from news article reporting the Victorian Government’s announcement of the cancellation of half of the freeway network proposed in the 1969 plan, Age, 29 March 1973, p. 3. However, the diagram shows the F2 survives from the Eastern Freeway northwards.

From this point forward, the Victorian Government and the Ministry of Transport were increasingly at odds with the CRB in regard to road-building priorities and philosophies.[57] Documents relating to the review of the transport plan from the Ministry of Transport reveal a greater sensitivity to the financial costs of the proposed network and the political consequences of imposing freeways on inner urban communities. One document commenting on the CRB’s plans states emphatically that the:

F2 south of Bell Street has a massive environmental and economic impact and cannot be justified. The benefits to road users would be insufficient to outweigh the monetary cost alone. Without this section of F2, the section north of Bell Street does not appear viable as a major freeway. This is because it unnecessarily duplicates an existing good highway and will create a significant problem at the freeway terminal (Note: the total cost of F2 is about $180 million!).[58]

These planning review documents demonstrate the CRB’s ongoing eagerness to build not only the F2 freeway but also many others first proposed in the 1969 plan. Referring to its statement dated April 1976, which acknowledged that ‘investigations south of Bell Street have been deferred for the time being’,[59] the CRB asserted that the ‘urgently needed’ road required a seven- to 10-year lead time (once an acceptable proposal was found, and the planning scheme amended).[60] The ministry, as part of its reassessment and ‘updating’ of the 1969 transport plan, critiqued the CRB’s plans, stating that it had based its ‘work on not providing for an ever increasing use of cars but rather on the attraction to public transport of as many trips as possible particularly those along dense corridors’.[61] Instead, the ministry proposed a number of smaller, less expensive, short-term projects to alleviate current problems rather than implementing a visionary but costly plan for meeting future demands.

The CRB seemed determined to maintain the plan for the F2 and F12 (an arterial road west from Hoddle Street along a Park Street alignment in Brunswick South), and the ministry was concerned about public perceptions of a lack of amendments to the plan since 1973. As the alignments were ‘labelled investigation areas in the Country Roads Board plan’, the concern was that:

The Government will be subject to criticism if these areas of the plan are published and still indicate that they are areas to be investigated … some considerable progress should have been made to resolve these issues ... it is possible to have other solutions which will no doubt be not as efficient as far as traffic movement goes, but will be less expensive and less environmentally destructive.[62]

Nonetheless, the CRB continued its F2 ‘investigations’ in spite of government doubts and community opposition, and acquired properties along the proposed F2 route (which it had been doing so since 1971) in Fitzroy and elsewhere, and generally going about its business in preparing for the road’s eventual construction.[63] As the Victorian Government slowly withdrew from this particular freeway solution, the CRB’s continued exploration of arterial road options for the inner north was reported in the media, creating the perception that the CRB seemed impervious to community concerns, was secretive and sneaky, and was largely pursuing its own agenda. G Houghton, a resident of Park Street Brunswick, writing to Minister Rafferty expressed concern about the F2–F19 termini being connected to the Tullamarine via Park Street. In concluding, he observed that the standard ‘reply that the CRB has no "no plans" (meaning blueprints) for a road in the area is quite unsatisfactory’, and drew attention to what he saw as deliberate obfuscation:

It is universally recognised, but ignored by the CRB and the previous Minister, that the process of ‘planning’ involves a great deal of preparation for the task of preparing blueprints. We seek an assurance that the process of planning will be discontinued.[64]

A letter from John Larkins of 504 Park Street, Brunswick, dated 13 May 1976, to the CRB chairman asked pointed questions about whether investigations had been conducted into turning Park Street into a main road and whether this had been required under the Country Roads Act 1958. Larkins stated:

I would myself have thought that the Board would have by this time appreciated that the construction of freeways leading into the central section of Melbourne is futile, and will do nothing to overcome problems associated with the use of motor vehicles. Overseas experience, as well as our own, must be well-known by the Board and, one might have hoped, demonstrated that the direct and indirect cost of freeway construction in inner areas was simply not justified.

Whilst one is prepared to accept assurances from the members of the Government that it is opposed to further freeway construction, it is, to say the least, alarming, to hear relatively senior officers of your Board boasting with pride of the ravages they, or the Board, are about to commit in the future. I dare say that such comments are made without the authority of the Board, but it can readily be understood that such reports do nothing to allay doubts about the intentions of the Board.[65]

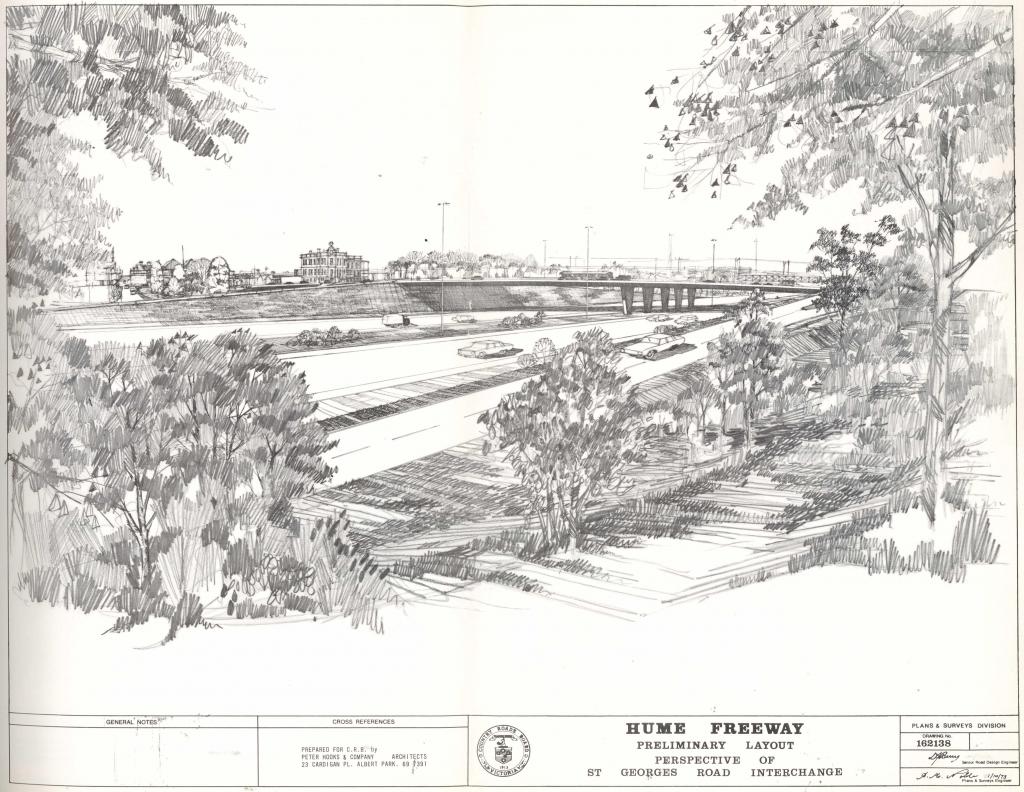

Figure 12: CRB Plans and Survey Division, Hume Freeway preliminary layout perspective of St Georges Road interchange, 1 October 1973, prepared by Peter Hooks and Company Architects, PROV, VPRS 242/P, Unit 1032, File C101174, Proposed Hume Freeway Bell Street to St Georges Road – reservation file. Merri Creek Primary School is replaced by an on ramp from St Georges Road in the foreground, with the Albion Charles Hotel still standing at the corner of Charles Street and St Georges Road on the horizon left of centre. The creek bed is no longer visible, presumably buried in a drain under the road. A tram is visible crossing on the bridge carrying St Georges Road across the freeway.

Deleting the F2

From October 1977 until June 1979, many of the letters received by the Ministry of Transport about the F2 proposal asked pointed questions about the properties acquired by the CRB and when they would either be sold back to the original owners or placed on the market, as confirmation that the route was no longer being considered. By 1978 the CRB had acquired 75 residential and commercial properties on the route between Bell Street and St Georges Road.[66] There were also questions being asked about whether the route reservation had actually been deleted from planning documents. Both sets of questions were met with responses that stated updates to planning documents had not yet been prioritised, but eventually the MMBW advised that it still wanted to keep the road reservation because it thought it would still be needed. For its part, the CRB supported the MMBW’s recommendation as the relevant planning authority.[67] Despite this last-minute bid to seek a reprieve for some kind of arterial through the Merri valley, the place remains undisturbed and has subsequently been restored to better health by vibrant community and volunteer efforts.

This attempt by the MMBW to keep an arterial route a live possibility revealed the ongoing consensus for road building in the planning bureaucracies. The intransigence of the CRB in the face of government concern at community disquiet and the potential for voter backlash were other such indicators. This has remained largely unchallenged despite a number of progressive Labor governments presenting policy priorities for advancing public transport. Ultimately, each successive government in Victoria has favoured roads construction regardless of stated policy intentions that have been taken to elections and dwindling community support for roads construction and growing support for public transport options.[68]

Figure 13: ‘Save Carlton Stop the CRB’ badges, University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092, Unit 13, File 14/6.

Clearly, in the early 1970s, there was a lack of community support for freeways on the grounds that they would diminish local amenity in inner urban suburbs. Concerned residents were willing and able to organise and coordinate across Melbourne to make the government and its agencies more responsive to environmental and community concerns, and to hold them to account for their decisions. The correspondence of the Ministry of Transport and the CA demonstrate the impact that a concerted community letter-writing campaign could have on decision-making processes and accountability. In conjunction with broader community organising and action, the letters from members of the public, community organisations and local councils contributed to the tensions that emerged between government and its road-building agencies. The anti-freeway campaign succeeded in saving most of the inner northern suburbs from bearing the burden of freeways through residential areas. This was part of a number of changes to policies affecting inner suburbs in Melbourne, and was just one of the signs of a dramatic demographic and political shift in Melbourne’s inner suburbs.

However, the roads policy network and the consensus on roads as a primary solution to mobility survived largely intact. Public transport initiatives were negligible for the next 40 years, especially compared to ongoing freeway and arterial road expansions. Successive governments and the planning bureaucracy learnt their lesson and never again unveiled the true extent of their intentions for road construction in such an unguarded way. Instead, ‘progress’ was made piecemeal, one project at a time, and always presented as a necessity to ease congestion. Tackling demand has never been raised as a serious political possibility. Much of the 1969 plan has now been built in one way or another. Most recently, the East-West Link would have created the link between the Eastern and Tullamarine freeways first envisaged in the 1969 plan and, though abandoned after a change of government, freeway expansion continues to the present, albeit with some major public transport improvements that have been a long time coming, such as level crossing removals and the Metro Tunnel.

Endnotes

[1] Graeme Davison with Sheryl Yelland, Car wars: how the car won our hearts and conquered our cities, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2004; Graeme Davison, City dreamers: the urban imagination in Australia, NewSouth, Sydney, 2016.

[2] Seamus O’Hanlon with Tony Dingle, Melbourne remade: the inner city since the 70s, Arcade, Melbourne, 2010; Seamus O’Hanlon, City life: the new urban Australia, NewSouth, Sydney, 2018.

[3] Tony Dingle and Carolyn Rasmussen, Vital connections: Melbourne and its board of works 1891–1991, McPhee Gribble (Penguin Books Australia), Ringwood, Vic., 1991.

[4] Max Lay, Melbourne miles: the story of Melbourne’s roads, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2003.

[5] Renate Howe, David Nichols and Graeme Davison, Trendyville: the battle for Australia's inner cities, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2014; Renate Howe and David Nichols, ‘A new relationship between planning and democracy? Urban activism in Melbourne 1965–1975’, in Planning models and the culture of cities: Proceedings of the 11th International Planning History Conference 2004, Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, Catalunya, Spain, 2004, pp. 1–11; Renate Howe, ‘The spirit of Melbourne: 1960s urban activism in inner-city Melbourne’, in Seamus O’Hanlon and Tanja Luckins (eds), Go! Melbourne: Melbourne in the sixties, Circa, Beaconsfield, Victoria, 2005, pp. 218–230; Renate Howe, ‘New residents—new city: the role of urban activists in the transformation of inner city Melbourne’, Urban Policy and Research, vol. 27, no. 3, 2009, pp. 243–251.

[6] Michael Buxton, Robin Goodman and Susie Moloney, Planning Melbourne: lessons for a sustainable city, CSIRO Publishing, Clayton South, Vic., 2016.

[7] John Stone, ‘Contrasts in reform: how the Cain and Burke years shaped public transport in Melbourne and Perth’, Urban Policy and Research, vol. 27, no. 4, 2009, pp. 419–434, available at <https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/a5e2a928-3594-492e-a21f-608574f69378/1/PDF%20(Accepted%20manuscript).pdf>, accessed 15 August 2020; John Stone, ‘Continuity and change in urban transport policy: politics, institutions and actors in Melbourne and Vancouver since 1970’, Planning Practice and Research, vol. 29, no. 4, 2014, pp. 388–404, available at <https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/04e7dba1-e4d5-4de3-85ef-fb140be9c6d6/1/PDF%20(Submitted%20version).pdf>, accessed 15 August 2020.

[8] Geoff Rundell, ‘Melbourne anti-freeway protests’, Urban Policy and Research, vol. 3, no. 4, 1985, pp. 11–21.

[9] Crystal Legacy, Carey Curtis and Jan Scheurer, ‘Planning transport infrastructure: examining the politics of transport planning in Melbourne, Sydney and Perth’, Urban Policy and Research, vol. 35, no. 1, 2017, pp. 44–60.

[10] ‘Cabinet to decide traffic plan’, Age, 18 December 1969, p. 1; ‘Prescription to relieve congestion’, Age, 18 December 1969, p. 9.

[11] Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Managing traffic congestion (report tabled 17 April 2013, PP No 221, Session 2010–13), Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 2013, p. viii, available at <https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/20130417_Managing_Traffic_Congestion.pdf>, accessed 10 April 2020. The need to factor induced demand into modelling is discussed at pages 24 and 29. See also Eric Keys, Chris De Gruyter and Graham Currie, ‘The problem with transport models is political abuse, not their use in planning’, Conversation, 10 December 2019, available at <https://theconversation.com/the-problem-with-transport-models-is-political-abuse-not-their-use-in-planning-127720>, accessed 10 April 2020. This assumption is declared in the published transportation plan by Wilbur Smith and Associates, The transportation plan, vol 3, Melbourne transportation study, prepared for the Metropolitan Transportation Committee, Melbourne, 1969, p. 47. See also Buxton, Goodman and Moloney, Planning Melbourne, pp. 20–21, 95–96, 107–108; Legacy, Curtis and Scheurer, ‘Planning transport infrastructure’, p. 49; Stone, ‘Continuity and change in urban transport policy’, pp. 399 and 401; Stone, ‘Contrasts in reform’, pp. 419–434.

[12] For a visualisation and explanation of this fundamental fact about moving people efficiently, see public transport consultant Jarrett Walker’s blog entry, ‘the photo that explains almost everything (updated!)’, available at <https://humantransit.org/2012/09/the-photo-that-explains-almost-everything.html>, accessed 15 August 2020. These ideas are discussed in greater detail in Jarrett Walker, Human transit: how clearer thinking about public transit can enrich our communities and our lives, Island Press, Washington, DC, 2011.

[13] See Davison’s discussion of automobilism in City dreamers, ch. 10.

[14] ‘New transport plan worries local councils’, Age, 19 December 1969, p. 3.

[15] The figures of freeway and arterial road works were originally given in miles, for a summary see Wilbur Smith and Associates, The transportation plan, p. 48. Lay, Melbourne miles, p. 200. As Lay notes, some commentators have argued that models other than Los Angeles were influential, see endnote 7, p. 257.

[16] PROV, VPRS 8609/P1 Historical Records Collection, Unit 32, Item 261 Australia's First Road-Rail Complex Melbourne Transportation Committee. The publication is undated but most likely would be c. 1972 by which time work on the freeway had commenced.

[17] Davison with Yelland, Car wars, p. 179.

[18] PROV, VPRS 8609/P1, Unit 60, MMBW, ‘Big survey will show our 1985 traffic wants’, in Master plan review, August 1966, p. 2.

[19] Wilbur Smith and Associates, The transportation plan, p. 32. The data and computer analyses are held by PROV, VPRS 10089 Computer Analyses [Metropolitan Transport Committee].

[20] Other draft public transport plans included a rail line to Tullamarine and the Doncaster East line as a branch from Alphington, PROV, VPRS 10090/P1 Correspondence Files, Unit 18, Item 394–39 Evaluation of Public Transport Plans 3, 3A, 3B diagram masters Melbourne and Metropolitan Transport Study.

[21] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number, Unit 125, File 76/236 Loop and Associated Projects (includes Eastern Railway Connection to Loop), GG Bennett to GJ Meech, 18 August 1972.

[22] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 125, File 76/236, Director of Transport GJ Meech to MURLA General Manager and Director of Engineering FG Watson, 29 September 1975.

[23] Buxton, Goodman and Moloney, Planning Melbourne, p. 98. See also ‘Doncaster railway line’, Wikipedia, available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doncaster_railway_line>, accessed 10 April 2020.

[24] Davison with Yelland, Car wars, p. 190; Howe and Nichols, ‘A new relationship’, pp. 5–7.

[25] Dingle and Rasmussen, Vital connections, p. 251.

[26] PROV, VPRS 8609/P1, Unit 60, MMBW, ‘17 million cars may use the ring road in a year’, in Master plan review, December 1963, p. 4.

[27] Dingle and Rasmussen, Vital connections, p. 313. The other three road projects were the Tullamarine Freeway, St Kilda Junction and the South Eastern Freeway extension to Toorak.

[28] Ibid., p. 315.

[29] PROV, VPRS 8609/P21 Historical Records Collection, Unit 345.

[30] Dingle and Rasmussen, Vital connections, p. 318.

[31] ‘Planners told: put public transport first’, Age, 5 October 1971, p. 1.

[32] Melbourne’s road building responsibilities until 1974 were divided between the CRB and MMBW, after which they were brought under the CRB, see: PROV, VPRS 421/ P11, Unit 14, File 72/3521, Report of the Board of Enquiry into the Victorian Land Transport System (the Bland Report) with comments by Victorian Railways Commissioners, Victorian Government Printer, Melbourne, 1972, pp. 161–162; Lay, Melbourne miles, pp. 53–54 and 201–202; Dingle and Rasmussen, Vital connections, p. 325.

[33] Davison with Yellend, Car wars, pp. 184, 190–219. Howe, Nichols and Davison, Trendyville, also provides several discussions of this miscalculation.

[34] PROV, VPRS 6347 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number System, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, media release February 1971.

[35] PROV, VPRS 6347 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number System, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, research proposal for the CRB, Dr Colin J Balmer, 25 June 1971.

[36] PROV, VPRS 6347 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number System, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, CRB Chairman REV Donaldson to Minister for Local Government AJ Hunt, 24 January 1972.

[37] PROV, VPRS 6347 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number System, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, newspaper clipping, Age, 22 February 1972, p. 3.

[38] PROV, VPRS 6347 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number System, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, CRB press statement, 22 February 1972, statement provided to Mr Hills of the Age, 21 February 1972, notes for the minister on the F2 freeway with handwritten annotations by REV Donaldson, 22 February 1972.

[39] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, Secretary F2 Regional Municipal Committee LD Cook to Minister for Local Government Alan Hunt, 8 March 1972.

[40] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, correspondence March to April 1972.

[41] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A, letter from East Brunswick Progress Association, 27 April 1972.

[42] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Part and B, 1978 Ministry of Transport document providing historical background to the government’s evolving position on urban freeways.

[43] ‘CRB stakes its claim to North Carlton’, Melbourne Times, 25 October 1972, p. 1.

[44] O’Hanlon has contested the often rosy view of the attractions of the inner city in the early 1970s by documenting the losses and displacements that took place there in City life and, with Dingle, in Melbourne remade.

[45] Howe, Nichols and Davison, Trendyville, p. xiv.

[46] Ibid., p. 32.

[47] Ibid., p. 19. A similar characterisation of the clash between Victoria’s planning bureaucracies and inner city residents in the early 1970s is made by O’Hanlon, City life, p. 138.

[48] Howe, Nichols and Davison, Trendyville, pp. 68 and 138.

[49] University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092 Carlton Association 1969–1980, Unit 5, file 4/5/2 Freeway Action 1971–1972, Freeway Action Group Newsletter, 5 February 1972.

[50] University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092 Carlton Association 1969–1980, Unit 5, file 4/5/2 Freeway Action 1971–1972, ‘We want you to spend 7 cents to save your home / Desideriamo che voi spendiate 7 centesimi per salvare la vostra casa’, undated [c. February 1972].

[51] University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092 Carlton Association 1969–1980, Unit 5, file 4/5/2 Freeway Action 1971–1972, letter from Aurora Calogero, 8 January 1972. The Freeway Action Group had gathered information through a variety of informal discussions with representatives from Metropolitan Transportation Committee; Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works; Country Roads Board; Civil Engineering Department, University of Melbourne; Town Planning Department, University of Melbourne; Loder Bayly & Associates, Consulting Engineers; Committee for Urban Action; Fitzroy Residents’ Association. See paragraph 3.3.1 in the report.

[52] Carlton Association Report, Freeway crisis, 29 March 1972, paragraph 4.2.6, University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092 Carlton Association 1969–1980, Unit 5, file 4/5/2 Freeway Action 1971–1972.

[53] Minister for Local Government AJ Hunt to the Carlton Association deputation, 3 February 1972, quoted from the Carlton Association Report, Freeway crisis, 29 March 1972, paragraph 5.3.4, University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092 Carlton Association 1969–1980, Unit 5, file 4/5/2 Freeway Action 1971–1972.

[54] This was gleaned from a leaked document from the CRB that is part of the CA collection, University of Melbourne Archives, Carlton Association Collection, 1984.0092 Carlton Association 1969–1980, Unit 14, folder 16/6 Country Roads Board Review of the Met Freeway Network 1985 [c. October 1971].

[55] ‘Premier halves freeway projects: He’ll look at other plans for the city’, Age, 29 March 1973, p. 3.

[56] ‘Editorial opinion: Putting people before cars’, Age, 30 March 1973, p. 9.

[57] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Parts A and B.

[58] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Part A, comments on CRB plan, 1977, p. 5. Many of the documents critiquing the CRB plan appear to have been authored by Senior Engineer JE Hartnett.

[59] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Part A, letter in review documents, 1977, p. 12.

[60] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Part A, letter in review documents, 1977, p. 21.

[61] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Part A, draft points on the Ministry of Transport’s review of the 1969 plan, 1977, p. 1.

[62] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 331, File 78/279 Transport Plan – Part A, Draft response to CRB plan, 1977, pp. 3–4.

[63] See PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part A.

[64] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part B, G Houghton to Transport Minister Rafferty.

[65] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part B, John Larkins to CRB Chairman, 13 May 1976.

[66] PROV, VPRS 6347 General Correspondence Files, Annual Single Number System, Unit 42, File 75/138 part C, CRB Chairman REV Donaldson to Minister of Transport JA Rafferty, 26 April 1978.

[67] PROV, VPRS 6347/P4, Unit 42, File 75/138 part C, Minister for Planning Hayes to Transport Minister JA Rafferty, 4 July 1978, forwarding letter from MMBW Deputy Secretary OTW Cosgriff, 1 June 1978, and letter from CRB Chairman REV Donaldson, 21 November 1978.

[68] See especially Stone, ‘Continuity and change in urban transport policy’, pp. 394–396.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples