Last updated:

‘Matters of life and death: girls’ voices in nineteenth-century coronial inquest files’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 19, 2021, ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Catherine Gay.

This is a peer reviewed article.

The Victorian Coronial Inquest Deposition archive, held at Public Record Office Victoria, provides important insight into the overlooked lives of nineteenth-century children. Some of the records include testimonies of child witnesses—rare examples of children speaking in history. Though matter-of-fact and often fragmentary, individual inquest cases and depositions can formulate an image of children’s worlds. This article focuses on cases in nineteenth-century Victoria in which girls died or were called as witness. On the surface, these records divulge discourses of anxiety around girlhood, societal regulations and behavioural ideals. Digging deeper, it is possible to gain entry into the lives of girls themselves. The daily activities of girls who died are described or inferred, illustrating their roles in family, work, school, play and relationships. The voices of girl witnesses are heard firsthand, adding veracity and layers of complexity to understandings of their family, friends and daily lives. The records contain evidence of material conditions and experience and can also be used to uncover intangible elements of existence, including emotions, relationships and thoughts. Through death we are offered an insight into life.

On Saturday 6 September 1879, Robert Ward drove his five children to his brother’s farm near Lake Goldsmith in rural Victoria.[1] Robert’s four daughters and son bundled into the cart, likely excited to see their cousins. When they arrived, the brothers went to cut chaff and left the children to play. Six-year-old Margaret, her brother Robert, sister Eliza and two cousins, one aged four and the other seven, went exploring. The children began to play near a bonfire, about a mile from the house, where a pile of rubbish from the garden was burning. They scavenged around and collected fresh sticks to put on the fire, determined to make it bigger. The children eventually sat near the fire, likely mesmerised by the growing flames. As they sat ‘the wind blew the fire with a blaze’. Glowing embers showered through the air, one landing on Margaret. Her dress caught alight. She screamed. The other children, realising what had happened, also began to scream. Margaret’s older sisters, Sarah Ann and Mary Jane, rushed to help. Her father and uncle also rushed over on hearing the commotion. Robert threw his daughter to the ground, smothering the flames with his own body. He managed to put them out, but she was badly burnt. He raced Margaret home, sending for the doctor from nearby Beaufort. But her burns were too severe and she died two days later on Monday 9 September. The coronial inquest, held promptly the next day, ruled that Margaret died from ‘injuries received … by her clothes accidently catching fire whilst at play’.[2] A family visit, for work and play, had turned into tragedy: a matter of life and death.

This harrowing story, laid out in a coronial inquest file, relays the story of a young life lost. Despite its terse, official style, it also briefly reveals numerous, interconnected and intimate aspects of nineteenth-century life: kin networks between rural families, friendship and siblinghood, farm work, daily dangers, family grief and judicial bureaucracy. Crucially, snippets of children’s play, relationships and daily life emerge from testimony provided at the inquest. Without this tragedy, Margaret and her family would probably have been lost to the historical record.

Despite their distressing subject matter, nineteenth-century Australian coronial inquest files are one of the only official archives that hold direct, substantial and plenteous examples of children’s voices. Children are not just shadowy subjects of discussion, but direct participants in the discourse. This article illustrates the ways in which Coronial Inquest Deposition Files (VPRS 24) from Public Record Office of Victoria (PROV) both give voice to the lives of children and challenge adult-centred histories. Most historians of children and childhood would agree that ‘children as a rule are some of history’s most silent subjects’.[3] Yet girls, who are generally the most silent subjects, are represented in this archive, as they were called to give testimony alongside boys, as well as adult men and women. Rather than being found in ‘the absences of the historical record’, as is often claimed by girlhood scholars, here girls are in its very midst.[4] Focusing on female youths in colonial Victoria, this article explores what can be learned by investigating the lives of girls who never became women. It demonstrates that the inquest archive, although produced for a very different purpose than the recording of ideas and experiences of girls, is a rich source of girlhood that can be read in a way that allows it to speak to a number of major themes in colonial girlhood studies.

Finding children’s voices

As Sarah Maza has observed, childhood and death are the only two universal human experiences.[5] Looking to inquest files reminds us of this very fact. For the better part of the nineteenth century, at least four in every 10 Australian children never made it to adulthood.[6] Perhaps it is this fragility of youth that has resulted in childhood receiving little attention from academic historians. While there are some historians of children and childhood, most historians focus almost exclusively on adult actors, adult action, adult institutions and adult stories. Australian scholars largely follow this international trend, despite some significant works on childhood published in the last decade.[7] A common retort to the dearth of children’s histories is that there is a lack of child-produced material from which to draw evidence, and that children are hard to find within the historian’s central domain—the archive.[8]

Yet state archives often hold a treasure trove of children’s voices. Court documents, in which children are called as witnesses, are just one example of children speaking in history. Criminal trial records sometimes contain children’s testimony, either as perpetrators or witnesses, yet these generally only represent certain sections of society.[9] Within the realm of legal documents, coronial inquest depositions are perhaps the most representative source. Death touches everyone, no matter their class, race, age or gender, albeit at varied frequencies and in different ways.[10] Although there are circumstances that mean some groups of people are more likely to be affected by death, it can happen to anyone—and does happen to everyone. Therefore, people that history may otherwise have overlooked—for example, non-literate working-class people—may have appeared at a coronial inquest and testified.[11] As Catie Gilchrist has shown in her study of Sydney coronial inquests from the 1860s and 1880s, such records, along with additional archival material, provide a view into ‘private lives that would otherwise remain unknown’ across a diversity of backgrounds.[12] Some demographics were overrepresented at the coroner’s court; for example, as Shurlee Swain discovered, unwedded, working-class Melbourne mothers were more likely to have their baby’s death deemed as suspicious and be dragged before the coroner in nineteenth-century Victoria than upper-class women.[13]

Inquests can take us away from the sensational or the exceptional to the everyday. The focus on crime and delinquency in some historical scholarship overshadows the ordinariness of many lives and the stories that can be drawn out of the quotidian. Inquests investigating accidental or intentional deaths take us deeper into children’s worlds. Such accidents, usually quick and unexpected, provide a snapshot of life. As many scholars have identified, childhood diseases were rampant in nineteenth-century Australia and, consequently, are the most common cause of child mortality.[14] This article, through its focus on inquests, moves away from the sick bed and into the family home, the workplace, the schoolhouse and the street.[15]

To illustrate the inquest archive’s potential scope and uses, this article draws from PROV’s Coronial Inquest Deposition Files (VPRS 24).[16] Originating from the State Coroner’s Office, the archive contains records of all deaths that were investigated by a coroner in Victoria between 1840 and 1985. The reasons for launching a coronial inquest varied, but could include when someone was slain, drowned or died suddenly. A coroner would assemble an all-male jury and call witnesses, including police and medical testimony, to ascertain the cause of death. Other scholars have expounded the benefits of PROV’s inquest archive, with Andrew J May et al.’s collaborative article the most recent example.[17] May et al. explore the scope and history of the archive. Their work shows that inquests can reveal much about life in Melbourne, especially around the themes of work, geography, race, family, relationships and community networks. However, while their article begins with the death of a boy, and mentions the deaths of children and infants, its overwhelming focus is on adult deaths and the information about life that can be drawn from their investigation.

What about children? Swain has utilised the inquest archive to gain insights into adult attitudes towards infant death, but there has been little focused research into the deaths of older Victorian children.[18] Numerous inquests into children’s deaths were held in nineteenth-century Victoria, with other children—siblings, other relatives and friends—testifying before the court. Though they have their limitations, these brief and specific testimonies can potentially illustrate a range of historical phenomena. Ultimately, as May et al. have noted, ‘evidence in a file such as this can tell us much more than the personal circumstances surrounding one unfortunate case’.[19]

Thousands of inquest files are digitised on PROV’s website with searchable index data.. Inquests that resulted in criminal trials are filed separately and are outside the scope of this paper.[20] I used a keyword search to filter potentially relevant records, initially searching for ‘female’ files. This enabled me to gather a sample of over 100 files of inquests into girls’ deaths. This method helped me to understand the workings of the archive and trained my eye to notice relevant cases, including common causes of death. Comprehensive quantitative analysis of the number of deaths of girls and children is not the focus of this study; instead, my focus is on the qualitative data that could be extracted from a sample of files.

Definitions of girls and girlhood prove their fluidity in this archive. As Kristine Moruzi and Michelle J Smith maintain, girlhood is an historically contingent and ‘complex category’. In the nineteenth-century world, the phase ‘girlhood’ was defined as being from childhood to the age of marriage, and was heavily influenced by intersectional factors of class and race.[21] Following on from this, my definition of ‘girl’ ranges from infancy until late teens, capturing a large span of life and experience that showcases the complexity and diversity of girls’ lives.

What does this sample of coronial inquest depositions reveal about girls and their lives in nineteenth-century Victoria? Most of the cases provide snippets of a life—one fateful day in a girl’s existence. Although fragmentary and to the point, they cover a huge swathe of places, people and incidents. As Patricia Jalland has noted, ‘death in Australia has always been a diverse and individual experience’, making it difficult to draw definitive patterns.[22] Yet individual cases and testimony can be assembled to formulate a composite image of girls’ lives and the world in which they lived. Insight can be gleaned into prevailing societal attitudes towards girls, discourses of anxiety around girlhood and the behavioural ideals girls were held to. Importantly, more than adult preoccupations are revealed. While the archive has its limitations, it serves as a potential mode of entry into the lives of girls themselves. Girls are the focus—the subject—in records that document their deaths. Their daily activities are described or inferred, including their roles in family, work, school, recreation and play. When girls are called as witness, we hear their voices firsthand (albeit mediated, and potentially abridged, through a court clerk), adding layers of complexity to explanations and understandings of their family, friends and daily lives. These records of material conditions and experiences can be used to uncover intangible elements of existence, including emotions, relationships and thoughts.

Societal attitudes towards girls

Coronial inquests into girls’ deaths reveal much about societal preoccupations with childhood and girlhood in nineteenth-century Victoria. The files, and their place within broader bureaucratic structures, reflect discourses of child protection, welfare and subsequent legislative controls that were placed upon young people over the century.[23] Regulations pertaining to inquests into child deaths indicate increasing societal interest and care for lost youth.[24] Such records also highlight the difference between ‘children’ and ‘childhood’ (and, by extension, ‘girls’ and ‘girlhood’)—the former being children’s own lives and experiences, and the latter concerning ideas and discourse about what adults thought of children.[25]

Coronial inquests expose growing societal anxieties about girlhood and, in particular, girls’ sexuality. Social theorist Catherine Driscoll conceptualises girlhood as a transitionary phase that society believes needs to be controlled—a space between childhood and womanhood in which a girl is perceived to be especially vulnerable.[26] Such thinking has its roots in the nineteenth century. Moruzi and Smith highlight the dilemma of the adolescent girl in the nineteenth-century world: ‘She represents a disturbing figure who is potentially beyond the control of family and unconstrained by societal norms’.[27] Girls were both sexually vulnerable and a sexual threat—boys’ sexuality did not incite similar levels of concern.

Deborah Gorham, in her study of Victorian-era English girls, explains that, in popular discourse, girls were characterised dichotomously as either ‘sunbeams’ or ‘hoydens’.[28] Morally pure girls—sunbeams—were viewed as the embodiment of goodness; they were cast as moral guides for fathers and brothers and were greatly admired. At the same time, such girls were also viewed as weak and vulnerable to the evils of the world. They could meet with an accident or be foiled by the morally impure; for example, they could be kidnapped, raped or even murdered. Conversely, hoydens were a threat. Deviant and rebellious, these girls were characterised by sexual impurity. They had the means and wiles to lure unsuspecting, usually upstanding, men into their sexual traps. Therefore, in the minds of British society, girls stood on the precipice of good and evil, at once a bastion against depravity yet vulnerable to its clutches.

Such discourse was also present in the Australian colonies. An 1857 article in the Melbourne Age reported on ‘the frightful prevalence of female depravity both in the city and the mining districts’.[29] The author blamed young women’s prostitution on drunkenness, lack of money and employment, and the abuse of girls in domestic service. Girls, it was argued, were not afforded ‘adequate protection’ from the ‘perils and temptations’ of colonial society and their depravity stemmed from both their own weakness and the evils of society.

The 1887 inquest into the death of Catherine (Kate) Davis highlights persistent community fears about girls’ vulnerability.[30] Fourteen-year-old Kate was found dead at the bottom of a mineshaft at Marong, near Bendigo. Newspapers picked up on what was dubbed ‘The Marong Mystery’ and its subsequent inquest, the Horsham Times reporting that ‘public opinion was divided as to whether she had committed suicide or a most diabolical outrage had been perpetrated upon her’.[31] At the inquest, Kate was described as rebellious—an inattentive student who was not only sexually active but also had multiple partners. The Kerang Times described her case as a ‘tragedy’: it was ‘as pitiful a story as can well be imagined’ and one of ‘stupendous vice on the part of a mere child’.[32] Thus, Kate was portrayed as vulnerable and culpable. The Kerang reporter blamed the boys she had sex with as much as Kate herself, concluding that she must have killed herself ‘as an escape from the horrible brutality to which she was subjected’. The author recommended raising the age of consent, as this would mean that the men responsible for Kate’s moral deviation and subsequent death could have been brought to trial, allowing justice to be served and preventing others from following the same immoral path. In 1891, four years after Kate’s death, the Victorian Crimes Act raised the age of consent from 12 to 16, making it illegal to ‘carnally know any girl under the age of sixteen years’.[33] Though it is unknown whether this particular case had any direct bearing on later changes, Kate’s death and the media attention it garnered demonstrates how increasing awareness of girls’ sexuality and vulnerability could lead to legislative interventions.[34]

To a certain extent, inquests reveal society’s discomfort around ideas of female reproductive health. There are many examples in the archive of unwed mothers driven to suicide and infanticide due to shame.[35] As Kate Davis’s case shows, shame could also be invoked in relation to pre-marital sex. Kate’s mother, Eleanor, did not mention Kate’s sexual activity at the first inquest. At the second inquest, after the post-mortem and witness testimony had revealed that Kate was sexually active, Eleanor said she had seen her daughter ‘keeping company’ with a young man. She implied that Kate was an unwilling participant in sexual activity:

I saw Kate lying on the ground on her back and a boy on top of her holding her down, as if trying to take improper liberties … I hit him with a stick across the back and he made away … I examined the girl and she had received no injury.

While Kate may indeed have been sexually assaulted, it is possible that Eleanor sought to mitigate her dead daughter’s shame, as well as her own, by insisting on Kate’s resistance.

A lack of knowledge about reproductive health may have materially affected Kate’s life and death. Eleanor, like most parents at the time, had never discussed menstruation with her daughter:

I thought she was too young to expect the fate of every woman, as to her courses—she was 14 years and 3 months old. I never instructed her what to do under such circumstances. If these discharges from natural causes have come on suddenly of course the girl would have been frightened, not knowing what they meant.

Menstrual blood was found on Kate’s underwear and it was implied that she may have fallen into the shaft, or committed suicide, because she did not understand what was happening to her body. Menstruation was rarely talked about outside of medical discourse in this era and little information survives as to girls’ sex education from their mothers. Eleanor’s statement supports historian Lynette Finch’s contention that, in nineteenth-century Australia, conversations about menstruation outside of medical discourse were taboo.[36]

While inquests can expose societal preoccupations with girls’ innocence, vulnerability, sexuality and responsibility, they are notably silent on issues of race. Most of the girls who appear in the inquest archive were of British or Irish birth or descent.[37] The only non-British or Irish name I came across was that of Lina Schmittenbecher who was born in New South Wales in 1857 to German parents.[38]

Girls’ voices

As we have seen, inquests can provide a picture of girlhood and how it was conceived and discussed in a particular historical, social and cultural context. But what can the archive reveal about girls themselves—their everyday lives and their interactions with others? The most striking aspect of the inquest archive is the presence of girls’ voices. Children’s ‘voices’, defined as ‘the opinions, emotions and behaviours of young people’, are often hard to find in conventional historical sources.[39] There are plenty of sources about children, created by adults, but very little that is written or created by children themselves. Girls are particularly voiceless, ‘doubly marginalized as both females and youth’.[40] Some historians read against the grain of the archive to uncover children’s experiences, including historians of Australian children who have used innovative methods to uncover the voices of youth in official documents.[41] Yet the archive tends to mainly reveal what adults thought about girls (especially, their attempts to control girls’ behaviour) rather than girls’ own thoughts and actions.

Although adults—and, crucially, male adults—controlled the arena of an inquest, it still provided a rare space for girls to speak in public and have their voices recorded. Often, the testimony of girls was brief, just a few lines on page, but sometimes a girl’s voice occupied multiple pages. Girls did not write their testimonies themselves. Instead, they were mediated through the court clerk who may or may not have recorded their statements verbatim; sometimes, in the interests of efficiency, testimony was summarised.

Scholars of childhood have noted the limitations of court archives. In their study of child labour in industrial England, Katrina Honeyman and Nigel Goose state, in relation to child rape allegations, that not only are there ‘gaps in [the] recorded evidence’, but also that ‘that which was recorded was filtered through the court recorder or the authors of later published reports’.[42] This assertion also applies to the inquest archive too. We do not know if everything a girl said was recorded. Nor can we be certain that what was recorded was actually said.

The formulaic nature of an inquest restrained what a girl could divulge. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, inquest forms contained pre-defined categories; details of the deceased, the jurors and any testimony were handwritten onto a single page per witness. Questions and answers about the circumstances surrounding a death meant that witnesses, including girls, were confined to relaying certain facts—not necessarily telling the whole story as they saw it. Public examination, too, may have affected girls’ testimony. In front of parents and other adult authorities, girls may not have been completely honest. If a young female witness felt that she had had some part in the death, or wanted to hide her actions, she may not have revealed everything she knew.

Some historians of girlhood, and children more generally, deliberately seek out exceptional cases—actions outside the norm, especially cases that that show girls’ rebellion and disobedience.[43] The danger of this approach is that girls who did not, or could not, rebel or speak out are obscured from our analyses. My research pushes against this search for, and privileging of, assertive agency by focusing on the everyday, for the quotidian should be of as much interest to the historian as the exceptional.

Work and family

Inquests highlight girls’ centrality to the workings of the family and the household. Girls were generally expected to attend to domestic tasks and daily chores. For example, Carolina Newman was helping her mother plant potatoes in the garden when she died; she fell over a bucket and likely died from internal injuries.[44] Annie Maria Welsch was collecting water for the household, a daily chore, when she drowned. Her sister Esther testified: ‘I heard my sister this morning tell me to look after the kettle while she was away and to make tea when it boiled’.[45] Girls often started helping around the house at a young age. Four-and-a-half-year-old Mary Kuniane drowned in Birch’s Creek in 1878 when she went to the river to collect water. Her mother declared: ‘She has been in the habit of going to the creek to fetch small quantities of water for household use’.[46]

Girls’ dresses sometimes caught fire while cooking for their families. Eliza Lucas, in her memoir, recalled her childhood home in Carlton where her ‘sister Fanny met her death … through the cursed Crinolines. They were the fashion in those days, she was dishing up the dinner when her dress caught fire’.[47] Fanny, who had just turned 17, provided essential domestic labour for her family. Inquest files corroborate the frequency of such deaths. Annie Nugent was helping her father on their farm in Donald when ‘he sent her into the hut to prepare dinner’.[48] Her dress caught fire while she was preparing the meal. Catherine Rebecca Noonan died in the paddock where her father was burning felled trees; one of the trees fell on her and crushed her.[49] Agnes Curnow was planting potatoes with her father at their farm near Daylesford in 1888. Her father lit a fire in a log; she drew near to warm her hands, but her dress caught alight and she died.[50] Girls like Annie, Catherine and Agnes were essential workers on family farms. As Kathryn McKerral Hunter has argued, daughters were indispensable, their unpaid labour ensuring the survival of many small family holdings.[51]

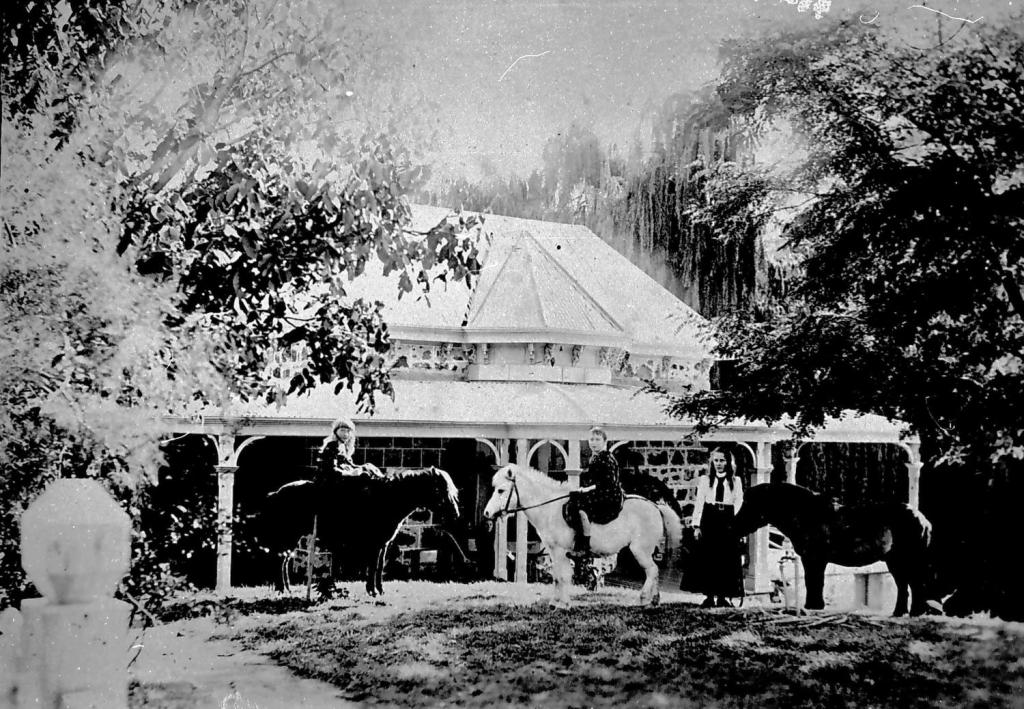

Figure 1: WH Smith, ‘Children looking out over farmland, Vic’, c. 1890 – c. 1899, State Library of Victoria, available at http://search.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/f/1o9hq1f/SLV_VOYAGER2148670

Eldest daughters were often responsible for the care of younger siblings. Toddler Euphemia May McKenzie had been left in the care of her nine-year-old sister, Ellen, when she drowned.[52] Ellen testified at the inquest, revealing the weight of her responsibilities:

I recollect yesterday morning my father and mother left home in the morning and left me to mind the house and the other children. Two of the children went to school ... I remained at the house with the deceased … I saw my father and mother leaving home and I [swept] the house.

Ellen told the jury that: ‘During the day she was with me, and never out of my sight’. Ellen was regularly left to care for her siblings. Her mother, Sarah, stated: ‘I left the deceased in charge of my eldest daughter Ellen McKenzie. I have left her before several times in her charge’.[53] Ellen was not able to go to school herself; being the eldest, her education was sacrificed to the care of her younger siblings. Her story resonates with that of Agnes McEwin, who, at 10 years of age, was sent to live with her mother’s friend who had a large family: ‘I was there over a year, neither Sarah or I went to school, I was kept busy helping Mrs Sandiland as she had several little children and had a great deal of work to do’.[54]

Toddler Louisa Ward drowned in 1857 when she was left with her 11-year-old sister.[55] Four-year-old Myrtle Greenwood was playing with matches when she caught on fire. Her sister May, called as witness, stated: ‘about 11 in the morning I was in the kitchen when I saw the deceased running out from the bed room to the dining room she was in flames’.[56] In 1888, Richard Winter and his wife left their four daughters with their ‘eldest Lydia sixteen years looking after the house’.[57] Lydia later testified: ‘I was left in charge of the children on Wednesday and Thursday’. A tree limb fell on her sister Charlotte on the way home from visiting a nearby family, killing her.

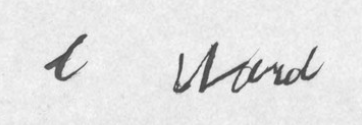

Inquests files also reveal girls’ work outside the home. Working-class children often began paid work around the age of 14 or 15, usually in domestic service, on farms or in factories.[58] Younger girls were often in less formal employment, like Agnes McEwin who stayed with family friends to help with daily tasks. Older girls often left home for work. The inquest archive holds records of girls who died while working (or in circumstances related to their work), such as 16-year-old Ellen Howe, a farmhand in Bacchus Marsh, who fell off her horse and died in 1881.[59] Her sister, Mary Jane, also worked at the farm and testified, pointing towards familial relationships in workplaces. Seventeen-year-old Lina Schmittenbecher was in service at a property near Middle Creek and died of ‘gastric fever running into typhoid’.[60] Elizabeth Murphy, aged 18, the newly employed servant at a Merton pub, died after falling from a horse.[61] She had struck up a friendship with the publican’s daughter, Annie Miller, who testified: ‘We went into the back yard, and there saw a horse tied to the fence we unloosed him, and deceased said that she would have a ride’. Annie’s testimony shows the rebelliousness of their act: ‘I did not tell my mother, nor did we ask the owner or rider of the horse, for permission to use it. She was anxious for to learn to ride and though that it was no harm in what we did’. Some girls just wanted to have fun.

Figure 2: C Mason & Co (Mason Bros), ‘Ruth, Enid and Maisie Hamilton with ponies at at Ensay Station, Gippsland, Victoria’, c. 1895, Museums Victoria, available at https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/items/770757

Although often impersonal and unemotional, inquest files can sometimes provide insights into the mental health of girls in and out of work. Occasionally, feelings seep through the otherwise terse testimony. For example, when seventeen-year-old Margaret Hall, a former domestic servant, committed suicide by drowning in the Yarra River, her brother testified: ‘She was down-hearted at times and at others cheerful … she was not well and had been ill for some time. She had to leave service on account of her state of health’.[62] Margaret’s friend Bella, who witnessed her death, stated: ‘Deceased had been drinking on the day she drowned herself. She did not drink at all … She had been ill and was low-spirited. I do not know of any sufficient reason for her taking her own life’. Bella had followed Margaret to the river and tried to get help, but she was too late to save her friend.

In 1888, 19-year-old Mary Grant also committed suicide by drowning in Melbourne. While her motive was unclear, it appears that her employer, Mr Rose, had been verbally abusive. Constable Davidson stated: ‘The man Rose is a foreigner and of an irritable disposition & it is said he has given the deceased no peace of mind since she has been in his service’.[63] Agnes Gordon, a young girl who witnessed Mary’s mental decline, said that ‘she was in misery’. According to Agnes, Mary told her ‘that she would drown herself. I asked what is a young girl like me to do’.[64] Mary may also have had a strained family relationship. Her brother, Edmond Grant, a labourer, was called as witness to her identity. His short, four-line statement read: ‘The deceased was my sister her name was Mary Grant her age was nineteen years. I have not seen her for some time’. It is evident Edmond and Mary were not close, though the reason for their estrangement is unclear. It is likely their mother had died in 1886 and father in 1873, leaving them with no parental support and perhaps a limited familial network.[65]

Kate Davis may also have had strained familial relationships prior to her death. Mary Pacholli, a 10-year-old girl in Kate’s class, said that the deceased ‘often told me that her mother was unkind to her and she told me that her mother tried to kill her many times and had threatened to drown her in a tub of water’. According to Mary, one day Kate’s mother, Eleanor, came to the school and ‘threw Kate over the fence and pelted a stick after her’.[66] Eleanor denied this cruel treatment.

Education

The inquests provide evidence of girls’ educative experiences and illustrate their increasing attendance at school. With the passage of the Victorian Education Act 1872, school became free and compulsory for children under 14 years of age. However, many children attended school prior to this.[67] For example, in 1854, 13-year-old Mary Ann Cotton was knocked over on Bourke Street by a careless cart driver while walking home from school with her sister.[68]

The inquest records show that some girls started school when they were very young. In 1857, four-year-old Ann Younghusband was run over by a van on her way to school. It was reported that Ann’s mother had ‘sent [the] deceased to school … at about nine o’clock’.[69]

Working-class girls who were employed during the day made an effort to attend school in the evening. Eliza Clarkson was walking to evening school along Smith Street, Collingwood, with two other girls when she was run over by a horse.[70] Not all girls enjoyed going to school. Kate Davis was a reluctant scholar. Her little sister Annie, 11 years old, testified: ‘Miss Elliott used to keep Katie in frequently for being backward in her lessons’. Once, Kate was ‘ordered by Miss Elliot to write the word “sulky” 250 times on the slate’.[71]

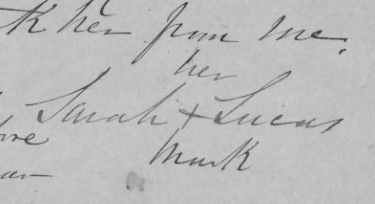

Evidence of increasing literacy can be gleaned in inquest records. In 1861, only half the number of school-aged children in Australia could read and write.[72] Emma Ward, the daughter of a cabinet maker, was one such girl. In 1848, she signed her own name after testifying to her sister’s death (Figure 3).[73] By contrast, her mother was illiterate, inscribing an X in place of her name. In 1857, Elizabeth Ward (unrelated to Emma), ‘not quite 11 years old’, also signed her own name to her statement.[74] The unevenness of education is shown in the case of Susan Lucas who died from scalding water in 1867. Her sister Sarah, aged nine, marked her statement with an X (Figure 4).[75]

Figure 3: Detail, Emma Ward’s signature, PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 49, Item 1857/178, Louisa Catherine Ward.

Figure 4: Detail, Sarah Lucas’s mark, PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 149, Item 1864/67, Susan Lucas.

In line with rising literacy rates, many girl witnesses could sign their own name by the late nineteenth century. Annie Davis signed hers in 1887, as did May Greenwood in 1897.[76] Yet, despite the Education Act, inquests reveal that not all girls were afforded an education. Myrtle Harriet McLean, aged nine in 1899, could not read or write and signed her name with an X.[77] She, her brother and her sister Effie had been playing with matches when Effie’s dress caught fire. Effie died from her injuries. Myrtle’s aunt, Eva Harriet Abbott, was also illiterate. It is likely that in remote Lake Boga, where the McLean and Abbott families lived, there was little opportunity to learn. A school was not opened in the district until 1892.[78] But it wasn’t just remote girls who missed out on going to school. After May Courtney died in 1899, her sister Dollie testified: ‘I do not know how old I am. I do not go to school’.[79] The Courtney girls lived with their single mother in Melbourne. A note added to Dollie’s statement read: ‘Witness could not write’. Some children were kept away from school to work. Kate Davis had apparently told her teacher ‘that she was kept at home to work’.[80] Despite the Act stipulating that all children between the ages of six and 14 were to attend school, ‘in practice, school attendance was often still irregular and the tuition rudimentary, regimented, and sometimes resented’.[81] Inquest files show that there was nothing universal about the so-called universal schooling Act.

Play and friendships

Girls’ play and leisure are sometimes elucidated through the inquest archive. The trip to and from school offered girls space to play with siblings and friends. In 1865, in Hotham (later North Melbourne), nine-year-old Alexandrina McDonald was playing in the street while walking home from school when she was run over by a cart. Her sister Margaret Ann testified: ‘I was coming over from school with my sister the deceased ... I had crossed the street and my sister was following me’.[82] Emma Stewart was run over while playing after school in La Trobe Street West in 1877.[83] That girls on their way to and from school were often out in public—on the street, playing with friends—complicates the popular idea of girls being kept close to home in the domestic realm.[84]

Girls sometimes played on the street by themselves and sometimes with others. Mary Charlotte Fretwell was playing alone on a Collingwood street in 1864 when she was run over. Shopkeeper Harriet Banks testified that she had ‘seen the child frequently playing in the street’.[85] Four-year-old Theodora Maxwell was also playing in the street by herself when she was run over by a cart.[86] Elizabeth Ward was playing with her brother and sister in front of their house when she died in 1848. Her sister Emma recalled: ‘I was playing with deceased and my brother … and deceased seeing her brother coming jumped from the body of the cart where she had been playing and fell on her face’.[87] Playing in carts was likely a common game in early Melbourne. For example, Eliza Chomley, daughter of a wealthy lawyer and politician who arrived in Melbourne aged eight in 1851, recalled that, ‘when the diggings broke out, we would drag my Uncle William’s carriage, left in our safe keeping, from the Coach-house, and play lucky diggers in it’.[88]

Eliza Chomley recalled that she and her siblings ‘were all great chums and companions, and … the boys joined in all our games, or rather invented them for us’.[89] Inquest records support this picture, suggesting that girls had friendships with siblings, cousins and neighbours across all ages and sexes. Five-year-old Matilda Collins was playing in her garden with other children when she was crushed by a tree branch in May 1865.[90] Margaret Kenworthy, aged five and living in Bendigo, fell from a swing. Her mother testified: ‘On Thursday evening the 16th instant the deceased went out to play with other children, about 6 o'clock in the evening’. Margaret’s friend, Ada Harris, aged 10, took Margaret to her place to have a swing. Ada stated: ‘Whilst I was swinging her, she fell backwards onto the ground’.[91]

In rural areas, girls seem to have spent much of their time with siblings, particularly their sisters. In 1881, five-year-old Alice Plum drowned while playing near the river at Wangaratta with her sister and another girl.[92] Ellen Guiney was riding a horse with her sister when she fell off and died from her injuries.[93] Elizabeth Knight was also with her sister when she died. In the summer of 1890, she and her sister Bertha ‘went to go for a bath in the swamp’ near their home in Yarock, north-west Victoria, and Elizabeth drowned.[94]

As we have seen, rather than being confined to the home, girls were often out of doors, playing independently, going swimming and going to school when they died. Yet the inquest records suggest that only girls under a certain age had these freedoms: girls over the age of 12 or 13 were more often found at home. Many older sisters were in the kitchen, in the house or otherwise employed in domestic chores—not playing—when an incident took place. Whereas boys frequently met their deaths falling out of trees, often while collecting birds’ eggs, no girls were found to suffer this fate.[95] While this points to the gendered nature of play and work, further research is needed on the differences and similarities between girls and boys lives and deaths in this period.

Conclusion

Children, especially girls, are often neglected within historical scholarship due to a perceived lack of sources and overwhelming preoccupation with adult lives. Their stories are often buried and are rarely brought to light. Yet, as this article illustrates, the official archive contains numerous examples of children’s voices within the formalities of coronial inquests. These inquests connect with broader discourses and legislation that reflect adult anxieties about childhood and girlhood. Importantly, they also transport us into girls’ worlds. They show that nineteenth-century girls in Victoria were essential workers in the family household, went to school (or not), and played with friends, siblings and other relatives. Coronial inquest depositions are thus a rich archive that, through death, provide insight into the fullness of girls’ lives.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 401, Item 1879/326, Margaret Ward.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Jennifer Helgren and Colleen A Vasconcellos (eds), Girlhood: a global history, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 2010, p. 4.

[4] Kristine Moruzi and Michelle J. Smith (eds), Colonial girlhood in literature, culture and history, 1840–1950, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2014, p. 1.

[5] Sarah Maza, ‘The kids aren’t all right: historians and the problem of childhood’, American Historical Review, vol. 125, no. 4, 2020, 1262, <https://doi.

org/10.1093/ahr/rhaa380>

[6] Aaron O’Neill, ‘Child mortality in Australia 1860–2020’, Statistica, 2019, available at <https://www-statista-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/statistics/1041779/australia-all-time-child-mortality-rate/>, accessed 2 July 2021.

[7] Carla Pascoe Leahy, Spaces imagined, places remembered: childhood in 1950s Australia, Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2011; Melissa Bellanta, Larrikins: a history, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2012; Simon Sleight, Young people and the shaping of public space in Melbourne, 1870–1914, Ashgate, Abingdon, 2013; Nell Musgrove, The scars remain: a long history of forgotten Australians and children’s institutions, Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, 2013. Historicist literary critics, such as Kristine Moruzi and Michelle J Smith, have made significant contributions to histories of girls and girlhood. See: Moruzi and Smith, Colonial girlhood in literature. Folklorists, such as Gwenda Beed Davey, have also made important contributions, though Beed Davey’s work centres on the twentieth century. See: Gwenda Beed Davey, Girl talk: one hundred years of Australian girls’ childhood, ARCADIA, North Melbourne, 2017.

[8] Maza, ‘The kids aren’t all right’, p. 1264; Emily Gallagher, ‘Hidden in plain sight: children’s art and writing in Australian archives’, Journal for the History of Childhood and Youth, forthcoming, 2021.

[9] Bellanta uses court records in her studies of larrikin boys and girls, but these usually only have the testimony of working-class larrikins. See: Melissa Bellanta, ‘The larrikin girl’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 34, no. 4, 2010, p. 508, <https://doi.org/10.1080/14443058.2010.519108

[10] Patricia Jalland, Australian ways of death: a social and cultural history 1840–1918, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2002. Recent scholarship by Lyndon Fraser revives Jalland’s thesis. See: Lyndon Fraser, ‘Death in nineteenth-century Australia and New Zealand’, History Compass, vol. 15, no. 7, 2017, p. 11, <https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12399>

[11] The inquests show a range of professions of the deceased and their parents. For example, Elizabeth Ward’s father was a cabinet maker, Mary Cotton’s father was a smith and Ellen Howe was a farmhand.

[12] Catie Gilchrist, Murder, misadventure & miserable ends: tales from a colonial coroner’s court, HarperCollins, Sydney, 2019, p. xiii.

[13] Shurlee Swain, ‘Birth and death in a new land: attitudes to infant death in colonial Australia’, The History of the Family, vol. 15, no. 1, 2010, pp. 25–33, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2009.09.003>

[14] Judith Raftery, ‘Keeping healthy in nineteenth-century Australia’, Health and History, vol. 1, no. 4, 1999, p. 277,

[15] Death from illness is investigated in some cases. See: PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 350, Item 1876/29, Lina Schmittenbecher.

[16] PROV, VPRS 24, Inquest Deposition Files.

[17] Andrew J May, Helen Morgan, Nicole Davis, Sue Silberberg and Roland Wettenhall, ‘“Untimely ends”: place, kin and culture in coronial inquests’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 18, 2020, pp. 34–44.

[18] Swain, ‘Birth and death in a new land’.

[19] May et al., ‘Untimely ends’, p. 35.

[20] PROV, ‘Inquest deposition files’, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/VPRS24/about>, accessed 2 July 2021.

[21] Moruzi and Smith, Colonial girlhood in literature, p. 1.

[22] Jalland, Australian ways of death, p. 2.

[23] Nell Musgrove and Shurlee Swain, ‘The “best interests of the child”: historical perspectives’, Children Australia, vol. 35, no. 2, 2010, pp. 35–37,

[24] Amy J Catalano concludes that parents have mourned lost children in the past and have not been indifferent to their deaths. See: Amy J Catalano, A global history of child death: mortality, burial, and parental attitudes, Peter Lang, New York, 2015, pp. 2–4. Jalland and Swain contend that British and Australian families mourned the loss of their children. See: Patricia Jalland, Death in the Victorian family, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996, p. 119; Jalland, Australian ways of death, p. 73; Swain, ‘Birth and death in a new land’, p. 25.

[25] Kate Darian-Smith and Carla Pascoe (eds), Children, childhood and cultural heritage, Routledge, New York, 2013, p. 5.

[26] Catherine Driscoll, Girls: feminine adolescence in popular culture and cultural theory, Columbia University Press, New York, 2002.

[27] Moruzi and Smith, Colonial girlhood in literature, p. 4.

[28] Deborah Gorham, The Victorian girl and the feminine ideal, Croom Helm, London, 1982.

[29] ‘Crime’, Age, 20 May 1857, p. 5.

[30] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 511, Item 1887/366, Catherine Davis.

[31] ‘The Marong mystery’, Horsham Times, 25 March 1887.

[32] ‘The Marong Tragedy’, Kerang Times, 8 April 1887.

[33] Victorian Parliament, An Act to Amend the Crimes Act 1890 and for Other Purposes, no. 1231, 23 December 1891.

[34] Melissa Bellanta, ‘Rough Maria and Clever Simone: some introductory remarks on the girl in Australian history’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 34, no. 4, 2010, pp. 417–28, <https://doi.org/10.1080/14443058.2010.519313>.

[35] For suicide while pregnant, see: PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 525, Item1888/185, Georgina Sone; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 527, Item 1888/434, Annie Urquhart. Infant girls who died in suspicious circumstances appear throughout the nineteenth century. See: PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 23, Item 1854/19, unidentified infant girl; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 167, Item 1865/242, unidentified infant girl; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 427, Item 1881/1054, unidentified infant girl; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 677, Item 1897/1083, unidentified girl.

[36] Lynette Finch, The classing gaze: sexuality, class and surveillance, Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards, 1993, Chapter 7.

[37] Richard Broome, Arriving, the Victorians, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, McMahons Point, 1984, p. 98.

[38] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 350, Item 1876/29, Lina Schmittenbecher. Births Deaths and Marriages New South Wales, see records: Lina Schmittenbecher, birth, 5818/1857. Parents registered as Henry Scmittenbecher (father) and Frances (née Frances Christy) (mother).

[39] Kristine Moruzi, Nell Musgrove and Carla Pascoe Leahy (eds), Children’s voices from the past: new historical and interdisciplinary perspectives, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019, p. 12, <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11896-9>

[40] Helgren and Vasconcellos, Girlhood, p. 4. Mary Jo Maynes, Birgitte Søland and Christina Benninghaus point out that girls have left fewer records than boys. See Mary Jo Maynes, Birgitte Søland and Christina Benninghaus (eds), Secret gardens, satanic mills: placing girls in European history, 1750–1960, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2004, p. 11.

[41] Kristine Alexander, ‘can the girl guide speak? The perils and pleasures of looking for children’s voices in archival research’, Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures, vol. 4, no. 1, 2012, pp. 134–35. Sleight, Young people; Bellanta, Larrikins.

[42] Katrina Honeyman and Nigel Goose, Childhood and child labour in industrial England: diversity and agency, 1750–1914, Taylor & Francis Group, Farnham, 2013, p. 25.

[43] For example, Frank Golding and Jacqueline Z Wilson have privileged industrial schoolgirls’ rebellion as uncovered in government reports and archives. See: Frank Golding and Jacqueline Z Wilson, ‘Lost and found: counter-narratives of dis/located children’, in Kristine Moruzi, Nell Musgrove and Carla Pascoe Leahy (eds), Children’s voices from the past, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019, pp. 305–329, <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11896-9_13>

[44] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 232, Item 1869/114, Carolina Wilhelmina Newman.

[45] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 487, Item 1885/1127, Annie Maria Welsh.

[46] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 384, Item 1878/354, Mary Kuniane.

[47] Eliza Lucas, ‘Autobiographical reminiscences’, 1848–1876, MS 12104, p. 8, State Library of Victoria.

[48] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 540, Item 1889/ 55, Annie Nugent. For secondary literature on fears around clothes catching alight, see: Barbara Young Welke, ‘The cowboy suit tragedy: spreading risk, owning hazard in the modern American consumer economy’, Journal of American History, vol. 101, no. 1, 2014, pp. 97–121; Alison Matthews David, ‘Blazing ballet girls and flannelette shrouds: fabric, fire, and fear in the long nineteenth century’, TEXTILE, vol. 14, no. 2, 2016, pp. 244–267, <https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2016.1139382>

[49] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 535, Item 1888/1244, Catherine Rebecca Noonan.

[50] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 533, Item 1888/1014, Agnes Jane Curnow. See also: PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 540, Item 1889/ 55, Annie Nugent. Annie was also helping her father in the paddock, stripping crop.

[51] Kathryn McKerral Hunter, Father’s right-hand man: women on Australia’s family farms in the age of federation, 1880s-1920s, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2004.

[52] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 575, Item 1891/53, Euphemia May McKenzie.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Agnes McEwin, ‘The girlhood reminiscences of Agnes McEwin 1858–1942’, 1938, MS 11690, State Library of Victoria.

[55] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 49, Item 1857/178, Louisa Catherine Ward.

[56] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 678, Item 1897/1183, Myrtle Greenwood.

[57] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 587, Item 1891/1386, Charlotte Winters.

[58] See: Sleight, Young people, pp. 96–97 for a thorough discussion of Melbourne children’s work.

[59] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 429, Item 1881/1269, Ellen Howe.

[60] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 350, Item 1876/29, Lina Schmittenbecher.

[61] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 713, Item 1900/51, Elizabeth Murphy.

[62] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 522, Item 1887/1535, Margaret Hall.

[63] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 523, Item 1888/15, Mary Grant.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Births Deaths and Marriages Victoria, see records: Mary Grant, death, 4043/1886; Edward Grant, death, 8552/1873.

[66] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 511, Item 1887/366, Catherine Davis.

[67] Education Act 1872 (Vic.) no. 447, available at <https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/vic8_doc_1872.pdf>, accessed 8 October 2021.

[68] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 23, Item 1854/30, Mary Ann Cotton.

[69] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 49, Item 1857/140, Ann Younghusband.

[70] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 415, Item 1880/218, Eliza Clarkson.

[71] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 511, Item 1887/366, Catherine Davis.

[72] Stuart Macintyre, A concise history of Australia, 4th ed., Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, 2016, p. 120.

[73] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 5, Item 1848/17, Elizabeth Ward.

[74] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 49, Item 1857/178, Louisa Catherine Ward.

[75] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 149, Item 1864/67, Susan Lucas.

[76] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 511, Item 1887/366, Catherine Davis; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 678, Item 1897/1183, Myrtle Greenwood.

[77] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 701, Item 1899/286, Effie Selina McLean.

[78] Lake Boga State School No. 2596.

[79] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 711, Item 1899/1362, May Courtney.

[80] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 511, Item 1887/366, Catherine Davis.

[81] Deborah Tyler, ‘Children’, in Graeme Davison, John Hirst and Stuart Macintyre (eds), The Oxford Companion to Australian History, Oxford University Press, 2001.

[82] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 166, Item 1865/106, Alexandrina McDonald.

[83] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 369, Item 1877/366, Emma Stewart.

[84] Mary O’Dowd and June Purvis (eds), A history of the girl: formation, education and identity, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018, p. 3.

[85] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 152, Item 1864/329, Mary Charlotte Fretwell.

[86] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 299, Item 1873/108, Theodora Maxwell.

[87] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 5, Item 1848/17, Elizabeth Ward.

[88] Eliza Chomley, ‘Memoir’, c. 1920, MS 9034, p. 10, State Library of Victoria.

[89] Ibid., p. 8.

[90] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 167, Item 1865/159, Matilda Elizabeth Collins.

[91] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 398, Item 1879/26, Margaret Pearson Stevens Kenworthy.

[92] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 426, Item 1881/973, Alice Lilian Plum.

[93] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 149, Item 1864/16, Ellen Guiney.

[94] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 560, Item 1890/317, Mabel Gertrude Knights.

[95] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 523, Item 1887/1637, George Liddell; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 342, Item 1876/414, John Terry; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 588, Item 1891/1475, Joseph Kent.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples

">

">