Last updated:

‘Nasty talk: anatomy of the first wife murder in the new colony of Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 19, 2021, ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Christina Twomey.

WARNING: This article discusses an historical case of domestic violence that ended in death.

Patrick Kennedy was convicted of murdering his wife Mary (née Costello) in 1851 and became the first man executed after Victoria separated from New South Wales. Revisiting the case through inquest and trial documents, and contemporary newspaper reporting, this article examines the legacy of family violence and the challenge to masculine privilege and entitlement at the heart of the case.

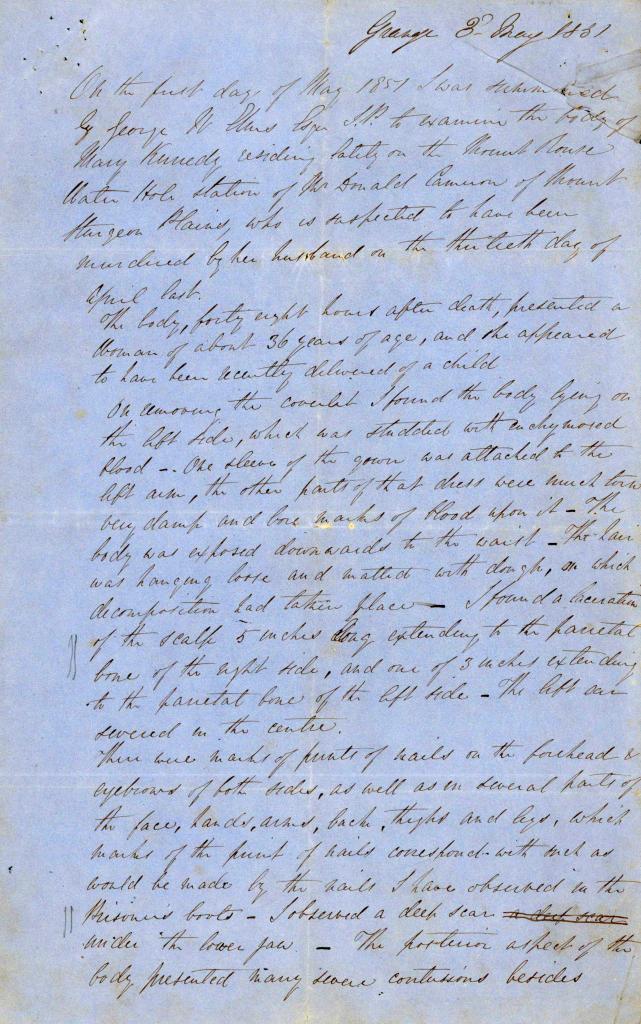

Late one evening in October 1866, Winifred Kennedy left her hat, mantle and gloves on her bed in a Melbourne boarding house and walked down to the docks. Almost two weeks later, her body was found near Coles’ Wharf. Winnie, as she was known, a dressmaker in her early twenties, had committed suicide by lowering herself into the water. There were no signs of violence on her body and she was not pregnant, a condition often suspected when a young, unmarried woman chose to take her own life. Her fiancée, with whom she had spent the evening talking and laughing, had told her to burn a distressing letter she had recently received. A former landlady was demanding unpaid board. The letter also contained veiled threats, insisting that Winnie tell her fiancée ‘the real truth how you came hear [sic] to me’ when she was a ‘fatherless child’. Winnie should ‘let him know the facks [sic] from your own lips’.[1]

Winnie Kennedy had been fatherless, and motherless, since she was seven years old. At the time she was orphaned, Winnie lived with her family at Mount Rouse in Victoria’s Western District. Her father was a shepherd on a large pastoral station. The family lived in a hut on the property and Winnie’s mother had recently given birth to her sixth child. Winnie’s father was said to be particularly fond of her, his eldest, trusting her to help out with the sheep during the lambing season.

Patrick and Mary Kennedy, Winnie’s parents, had married in Melbourne in the early 1840s.[2] Both were assisted immigrants from Ireland. Patrick was 19 when he disembarked in Melbourne in 1842.[3] Mary Costello, as she was then, had landed the previous year as part of an Irish family group from Galway. On board her immigrant ship were her sister, ‘Biddy’, and two older brothers.[4] Mary and her siblings were in their 20s, and were precisely the type of immigrants the government was keen to encourage: willing workers for the colony’s nascent industries and women with domestic skills who might reasonably be expected to marry and start a family. They represented the last great surge of immigrants before the gold rushes of the 1850s.[5]

Until April 1851, Patrick and Mary’s life appeared to proceed much as they, and colonial population and policy planners, had hoped. They married quickly after arriving in Australia and within eight years Mary had given birth to six children. A shepherd with whom Patrick worked on the pastoral property declared that they ‘were as happy a couple as I ever met with’ and that Patrick was ‘attached to his children’; another reported that he had never seen them quarrel.[6] With a touch of melancholy, he added that ‘there was not a better woman in the country’ than Mary.[7]

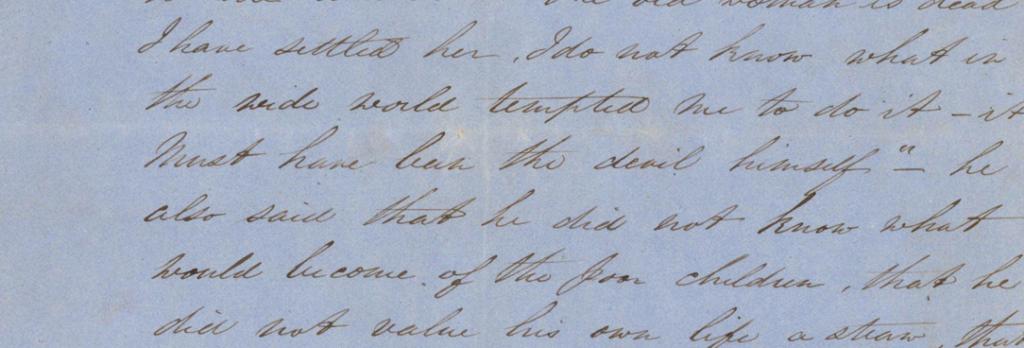

The ostensibly idyllic life of the Kennedys and their young family, tending sheep on a volcanic plain, exploded on the afternoon of 30 April 1851. It was nine years to the day since Mary and Patrick had married. Three of their children had survived infancy and Mary had just given birth to another baby. Mary served lunch to Patrick and the other shepherds in their hut. She did not herself eat any food. The men were nursing hangovers from the previous evening and Patrick appeared to be spoiling for a fight. He started first on his fellow shepherd John Williams, who had been mildly critical that Patrick seemed disinclined to go back out to tend the sheep and had sent his seven-year-old daughter Winnie, ‘a good shepherd’, instead.[8]

The next interaction between the adults inside the hut is difficult to unravel, but one interpretation is that Patrick implied that his wife’s sexual services could be offered in exchange for access to a horse. Patrick wanted to borrow Williams’s horse, and quipped that he had once been offered ‘£60 and a mare for the old woman—meaning his wife’.[9] Williams established that the couple were indeed married, and somewhat facetiously remarked ‘well you have great respect for your wife, as you would not sell her for this world’s goods’.[10] This attempt to defuse the situation enraged Patrick, who threatened to kill Williams, bury him and take off with his horse. Mary also chimed in: ‘Don’t be using such nasty talk, Patrick’.[11] Williams removed himself from the situation and went to check on the sheep. By the time he returned to the hut a short time later, Mary was crying. ‘He is angry’, she said, ‘he wants to vent his spite on me’.[12]

At the heart of the exchange between Williams and the Kennedys was the denial of masculine privilege. Patrick Kennedy wanted a horse, and he felt entitled to offer his female possession, his wife, in exchange for it. In response, Williams constructed this assertion of power as illegitimate—respect, not ownership of women, should sit at the heart of a marriage. Mary herself also censored Patrick, and thereby allied herself with another man, by asking him to refrain from ‘nasty talk’ to one who had challenged him. As British theorist Jacqueline Rose writes, following Hannah Arendt, ‘it is illegitimate and/or waning power that turns most readily to violence’. Patrick certainly possessed what she identifies as ‘a sense of entitlement prepared to turn nasty’.[13]

One word that recurred throughout the accounts of what followed convinces me that witnesses to that event had only a very partial understanding of the relationship between Patrick and Mary. That word is ‘brute’. All the witnesses to Patrick’s violent assault on Mary report it being uttered, not by her, but by him. When Williams attempted to intervene between Mary and Patrick, warning Patrick that he should not ‘unman’ himself by striking a woman, particularly one who had so recently given birth, Patrick initially seemed demur. Then he paused, grinned, and belted Mary on the shoulder and said to her ‘you brute!’. After knocking Mary to the ground, dragging her around by the hair, and repeatedly kicking and punching her in the face, Patrick bellowed: ‘speak, you brute!’[14] ‘Your two brothers beat me in Melbourne and I’ll have satisfaction out of you.’[15]

Patrick’s taunting of his wife during a ferocious assault suggests to me that violence was a feature of this marriage before the fatal attack. When an aggressor utters a phrase that more rightly belongs to his victim, when he smiles as he is about to enact violence, it seems more like habit than happenstance. Demanding that Mary speak when she was rendered almost unconscious by a vicious beating implies that, for Patrick, her words, what he considered to be her sharp mouth and her over-reaching brothers, had landed her there.

Figure 1: Page from the statement of John Williams in the criminal trial brief for Patrick Kennedy, PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, 1-112-15, Patrick Kennedy.

Williams, himself intimidated by Patrick’s threats when attempting to intervene, thought that maybe it was a good idea to send in Winnie to ‘pacify’ her father.[16] In hindsight, it seems a remarkable act for a grown man to send a young girl straight into the sights of a man in a homicidal rage. Instead of being able to calm her father, Winnie witnessed the attack turn fatal. No one mentioned the child again in their depositions, but it is clear from the chronology of events that she was present. Her mother was limp, she was half-naked, and the hut was covered in blood; her father would not stop the attack. Williams and another shepherd again tried to dissuade Patrick. He paused, repeated the feign of calm, then ‘jumped on the body and began to dance on it’ in his hobnail boots.[17]

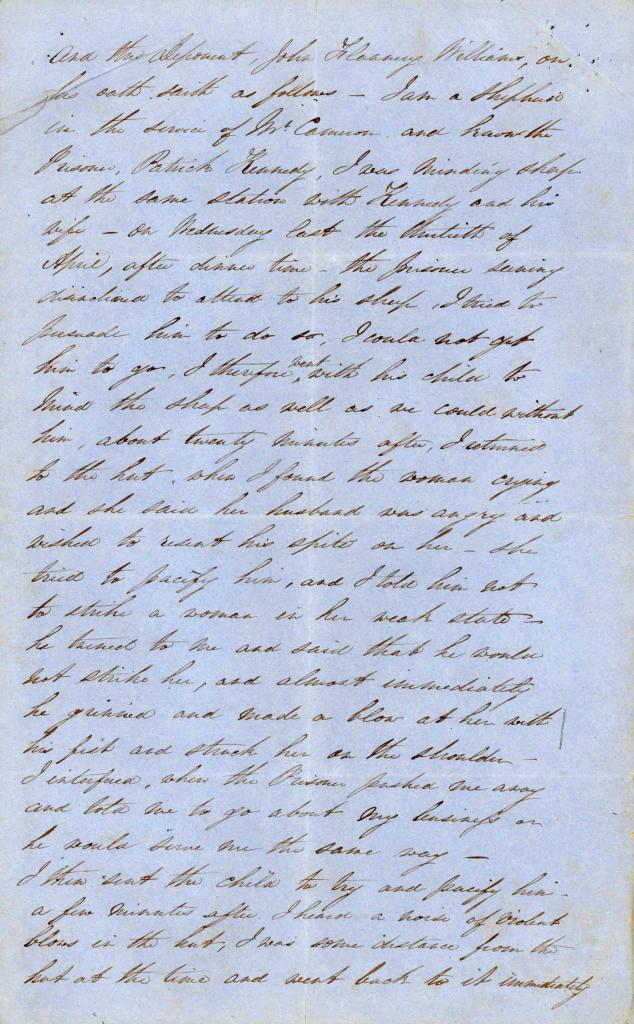

Figure 2: Page from the statement of Benjamin Carter, one of the other shepherds who witnessed the murder, in the criminal trial brief for Patrick Kennedy, PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, 1-112-15, Patrick Kennedy.

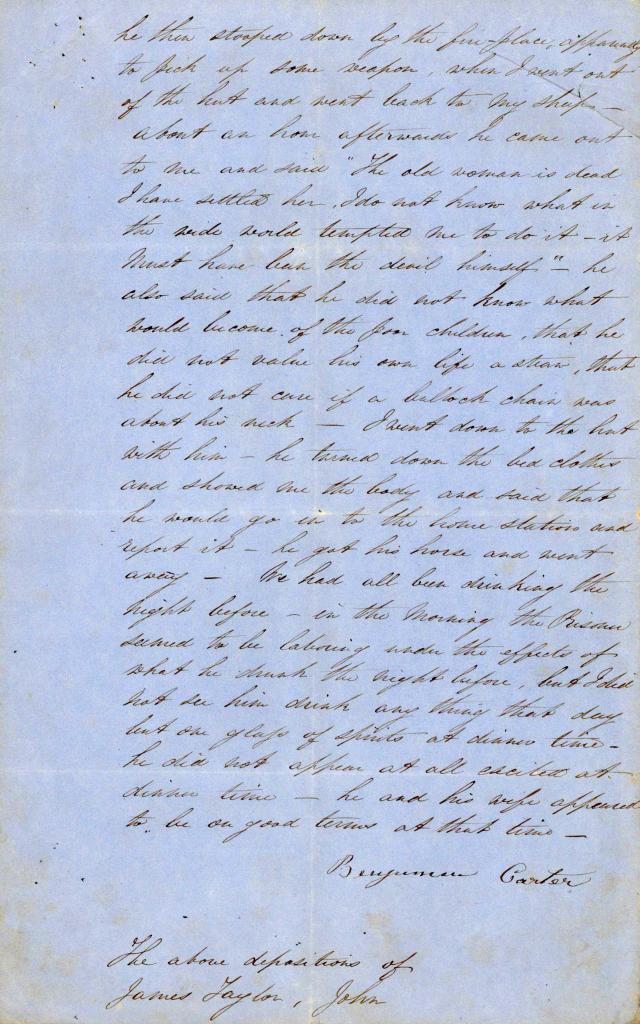

It is scarcely possible to imagine the violence that seven-year-old Winnie saw, how ravaged was the body of her mother, or to comprehend how witnessing such distressing scenes affected her. The surgeon who later examined Mary stated that the lacerations on her face and skull were so deep that bone was exposed, and that her entire body, including her face, was covered in indentations from the nails in Patrick’s boots.[18] Winnie was left alone with her mother while the shepherds went to find the police and a doctor. By the time they returned, Mary’s lifeless body had been moved to the bed. Someone had washed her face and the top half of her body. I imagine that it was Winnie.

Figure 3: Page from the statement of the surgeon John Creelman, in the criminal trial brief for Patrick Kennedy, PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, 1-112-15, Patrick Kennedy.

Patrick offered no defence. He could not make sense of his actions and claimed the devil got into him. Jacqueline Rose, again, offers an insightful reading by suggesting that violence against women ‘is a crime of the deepest thoughtlessness. It is a sign that the mind has brutally blocked itself’.[19] A later commentator described Patrick as a monomaniac, not a lunatic, parsing the distinction by suggesting that a least lunatics had sane moments.[20] Patrick did say of his 36-year-old wife: ‘The old woman is dead. I have settled her’.[21] He was found guilty of his crime, with no latitude given for his mental state. The prosecuting attorney in the case blamed a drinking bout, arguing that drunkenness was the ‘source of all the evil that occurred in the colony … [and] the curse of the working classes’. He claimed that ‘no malice had been shown, no quarrel’.[22] But this was a crime full of spite, and rage and glee at the assertion of control. How many murderers ‘dance’ on their victim, in hobnail boots?

Alcohol was often a factor in crimes against women, then as now. Historians have argued that some violence in working-class homes was tolerated, and that neighbours were often reluctant to intervene in disputes between a man and his wife.[23] Yet this case carries neither of those hallmarks: Patrick was sober when he beat his wife to a pulp, and other men present repeatedly tried to intervene but were frightened off when he threatened to turn on them. They explicitly used language that described his behaviour as unmanly, and pointed to the fragility of Mary in her immediately post-partum state. The result of such chiding was to rile Patrick into an even greater rage.

Patrick was ultimately sentenced to death for his murder of Mary. In November 1851, he became the first man executed in the newly created colony of Victoria, after its separation from New South Wales. Several reports claimed that the crowd of almost 800 people who came to watch the execution was dominated by women.[24] The crime itself had a certain infamy at the time, both its commission and the execution documented by the well-known chronicler of early Melbourne, ‘Garryowen’.[25] The first executions in Port Phillip, before separation from New South Wales, were of two Tasmanian Aboriginal men, Tunnerminerwait and Maulboyhenner, an event that, in recent years ,has been commemorated, revisited and analysed anew.[26] The high-profile execution of a wife-murderer also warrants revisiting, as uncovering and understanding gendered violence is also critical to histories of justice.

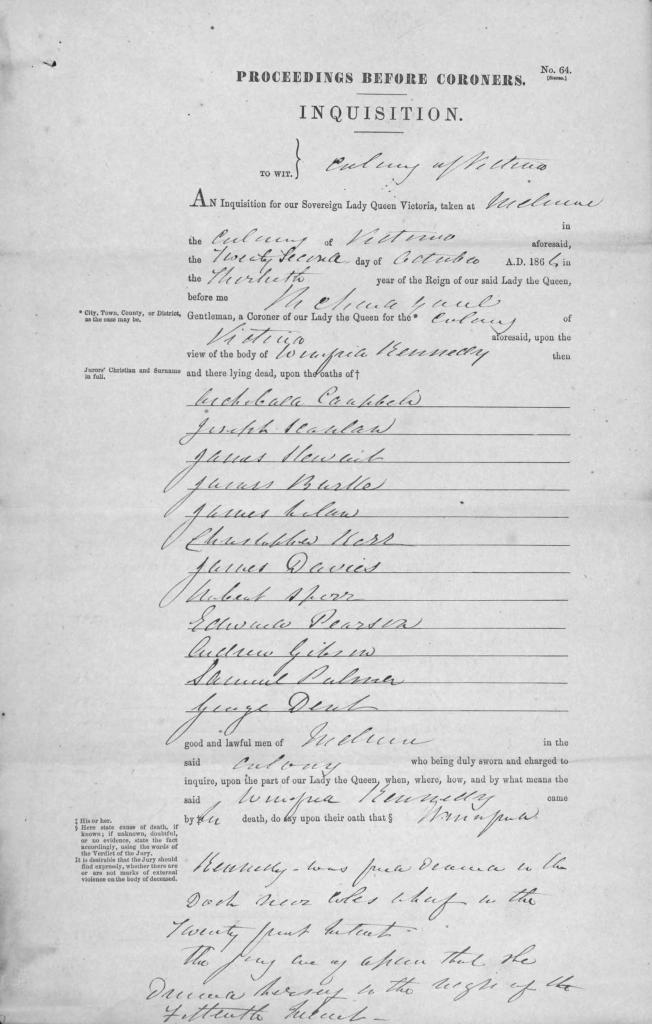

Figure 4: Inquest of Winifred Kennedy, PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Unit 185, Item 1866/316.

Mary’s brothers might have been prepared to take on Patrick during her lifetime, but in later life, one of them was proud of his status as a Port Phillip ‘pioneer’ and could not bring himself to mention the notoriety of Mary’s murder.[27] Perhaps he recalled that Patrick had mentioned the brothers’ behaviour when beating Mary to death. When Mary Kennedy, her mother’s namesake, was interviewed as part of the coronial inquest into her sister Winnie’s suicide, she reported that Winnie had been ‘in low spirits’ for the last year. Mary would have been only four years old at the time of her mother’s murder. We cannot know if her reference to ‘low spirits’ was an acknowledgement of a childhood trauma that continued to haunt Winnie, and if a cruel reference to it by an insistent landlady was too much for her to bear. When completing Winnie’s death certificate, I fancy that it was Mary who stated their father’s name was Thomas, not Patrick. It might be important to excavate such stories for public reckoning, but in the immediate family, burying them might have been the only way to survive. And sometimes even that could not prevent the impact of family violence carrying its terrible legacy to a sad end at Coles’ Wharf.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, Unit 185, Item 1866/316 Inquest Winifred Kennedy: Margaret Dowling to Miss Kennedy, 10 October 1866; Deposition of John Taylor, Winnie’s fiancée; Detail about the condition of the body from report of Dr John Neild.

[2] Patrick Kennedy married Mary Costello on 30 April 1843 at St Francis Church, Melbourne.

[3] Patrick Kennedy arrived on the Himalaya on 26 February 1842. He was from Galway, 19 years old and illiterate.

[4] Mary (aged 23), Biddy (aged 20), Walter (aged 28) and Patrick (aged 26) Costello arrived on the Argyle in April 1841. Mary and Biddy could read; Walter and Patrick were illiterate. All were from Galway. New South Wales, Australia, Assisted immigrant passenger list.

[5] John McDonald and Eric Richards, ‘The great emigration of 1841: recruitment for NSW in British emigration fields’, Population Studies, vol. 51, 1997, pp. 337–355.

[6] ‘Supreme Court’, Argus (Melbourne), 20 August 1851, p. 2.

[7] Benjamin Carter in Ibid.

[8] ‘Supreme Court’, Geelong Advertiser, 21 August 1851, p. 2.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jacqueline Rose, On violence and on violence against women, Faber & Faber, London, 2021, p. 39.

[14] ‘Supreme Court’, Geelong Advertiser.

[15] ‘Supreme Court’, Argus.

[16] PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, Patrick Kennedy, Statement of John Williams.

[17] PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, Patrick Kennedy, Statement of Benjamin Carter.

[18] VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, Patrick Kennedy, Statement of John Creelman, Grange, 3 May 1851.

[19] Rose, On violence, p. 174.

[20] ‘The execution of Patrick Kennedy for murder’, Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 1 November 1851, p. 1.

[21] PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Unit 12, Patrick Kennedy, Statement of Benjamin Carter.

[22] ‘Supreme Court’, Argus.

[23] Alana Piper and Ana Stevenson, ‘Challenging gender’, in Alana Piper and Ana Stevenson (eds), Gender violence in Australia: historical perspectives, Monash University Publishing, Clayton, 2019, pp. vii–xix.

[24] ‘The execution of Patrick Kennedy for murder’; ‘The chronicles of early Melbourne’, Herald (Melbourne), 8 December 1882, p. 3, reprinting of account by famous chronicler of early Melbourne, ‘Garryowen’, pseud. of Edmund Finn.

[25] Garryowen, The chronicles of early Melbourne 1835 to 1852, historical, anecdotal and personal [1888], Ferguson and Mitchell, Melbourne, 1972, vol. 1, pp. 391–392 and 405–408.

[26] Kate Auty and Lynette Russell, Hunt them, hang them: ‘the Tasmanians’ in Port Phillip 1841–2, Justice Press, Melbourne, 2016.

[27] Dorothy Wickham (ed.), In the days when the world was wide: a narrative of the pioneering experiences of Patrick Costello 1841–56, Ballarat, 1996.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples