Last updated:

‘Therapeutic labour and the sanatorium farm at Greenvale (1912–1918)’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 19, 2021, ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Rebecca Le Get.

This is a peer reviewed article.

By the turn of the twentieth century, tuberculosis was understood as a public health concern in Australia. In response, state governments began to construct specialised hospitals, called sanatoria, for the isolation, education and treatment of tubercular patients. The treatments undertaken in these institutions could involve work in the outdoors, ranging from assisting in maintaining the sanatorium buildings to farm work. But, to date, there has been little examination of the variety of outdoors work that was utilised within these Australian institutions, or which sanatoria instituted these regimens.

The Greenvale Sanatorium, established in 1905 north-west of Melbourne, expanded the role of agriculture in patient therapy in 1912 to a scale that had not previously been seen in Australia. The farm work undertaken at Greenvale is documented in the transcript of a 1918 Royal Commission into the management of the institution, and other records held by Public Record Office Victoria.

Greenvale Sanatorium’s use of farm work as therapy, and as a cost-saving measure, can be traced over time. By examining the sanatorium farm at the time of the Royal Commission’s investigation, and in its wake, it is possible to draw attention to the intrinsic role that patient labour played in early twentieth-century sanatorium operations, and how the land used for farming has contributed to Greenvale’s appearance in the present.

Introduction

In October 1914, Dr Alfred Austin Brown, physician and superintendent of Victoria’s first specialised public hospital for the treatment of tuberculosis, Greenvale Sanatorium, submitted a report to the chief Victorian health officer. According to the Freeman’s Journal, Brown outlined an expansive proposal to ‘increase the usefulness of the institution’ he had headed since 1911, developing its pre-existing farm so that ‘opportunities are afforded industrious patients to obtain a knowledge of rural industries, and fit them for country employment’.[1] Alongside the traditional open-air wards of a sanatorium, the superintendent was proposing that his tuberculous patients combined re-skilling for their future employment after discharge with task-oriented work that was believed to have therapeutic benefits.

Tuberculosis and its treatment in early twentieth-century Victoria

Tuberculosis was first recorded in Australia in 1800. By the second half of the nineteenth century, it was increasingly conceptualised as a public health issue.[2] Within the colony, later state, of Victoria, indigent tuberculous could turn to benevolent asylums or specialised charitably run institutions such as sanatoria. Working men, and their dependants, could be treated by a ‘club doctor’ if they had joined a friendly society before showing symptoms. Those with the means to afford personal treatment would pay to see a private physician.[3] Once tuberculosis was recognised as contagious, preventing the spread of the illness came to be seen as the responsibility of state governments.[4]

Prior to the development of effective antibiotics in the mid–twentieth century, treatments in charitable, private or public sanatoria were not rigorously tested to determine efficacy and could not cure tuberculosis, though they may have increased a patient’s quality of life. Instead, treatments, particularly in public sanatoria, reflected the social and financial concerns of governments that were increasingly expected to care for individuals who, as their illnesses worsened, were unable to work.[5] This led to an emphasis on sanatorium patients receiving rehabilitative care so that they could return to the workforce and remain financially independent, including retraining for occupations that were considered to be more appropriate. Contemporary proposals, such as Brown’s, justified retraining in rural, outdoor occupations, such as farm work, as the means to extend discharged patients’ working lives, while also reducing their infective risk to the wider community. It envisioned a romanticised, rural arcadia for the tuberculous that contrasted with the dense, poorly ventilated, urban homes where the majority of working-class sanatoria patients—those who could not afford private treatment—lived.[6]

An emphasis on beneficial work for sanatoria patients that increased in difficulty over time appears to have been spurred by concern that the traditional method of treatment in European-style sanatoria required long periods of rest.[7] With rest came the perceived risk of ‘indolence or laziness and dependence on others’ after discharge, which institutions sought to discourage.[8] Subsequently, such concerns were combined with the theory of auto-inoculation. This gave graduated sanatorium labour a scientific rationale and explained why institutions for the working classes incorporated therapeutic labour, while the upper classes were treated with enforced bed rest and rich meals.[9]

Auto-inoculation theory proposed that patients would produce antibodies while exercising that would attack the poisonous tuberculosis bacteria within their lungs and assist the individual in recovering their health.[10] Antecedents can be seen in the British workhouse tradition where labour was used to keep inmates occupied while also providing economic benefit to the institution.[11] If this labour or exercise included agricultural activities such as digging, tilling or seeding, then it was a welcome financial side effect of this new treatment paradigm.

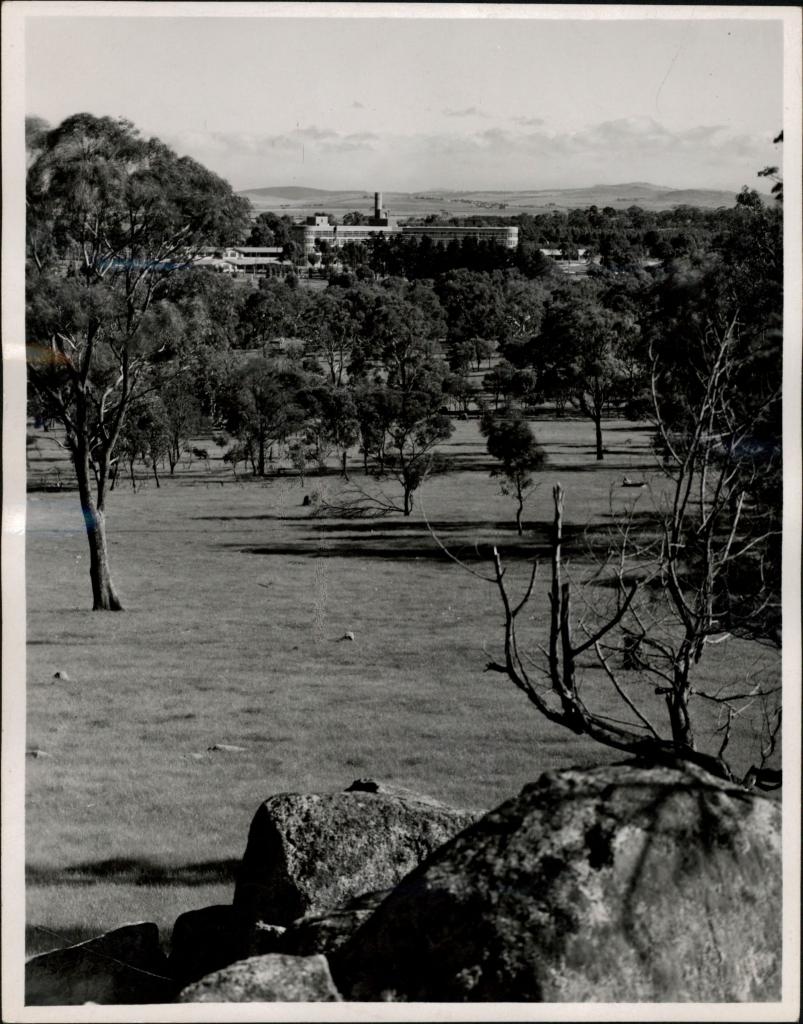

Historians such as Flurin Condrau suggest that, in Europe, ‘the erection of a sanatorium often jump-started other regional infrastructure by putting a village or small town on the map’; however, this does not appear to have been the case at Greenvale.[12] In fact, the region, 20 kilometres from Melbourne, was deliberately chosen because it was remote from urban areas and would hopefully remain rural for many years. Such isolation not only discouraged visits by friends and family, but also required the institution to be largely self-sufficient due to the difficulty of having food and water delivered in a timely manner.[13] This, in turn, drove the use of patient labour in running the institution: in theory, patients thus treated avoided developing a ‘dependence on others’ and instead became self-sufficient members of society.[14] This approach allowed the site to eventually accommodate large-scale farm operations (Figure1).

Figure 1: The wider area around the sanatorium remained rural for decades after the institution was established, as this photograph, c. 1947, shows. PROV, VPRS 10516/P3, Greenvale Sanatorium, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/AC666424-F7EA-11E9-AE98-9FB721910AF3>.

At the time of Brown’s 1914 proposal, Greenvale’s sanatorium already included a small-scale farm for patient education and treatment. Even so, Greenvale is likely to have been the first Australian institution to attempt a large-scale, graduated labour regimen for patients with active tuberculosis. The farm’s establishment in 1912 predates the opening of farms associated with other Australian sanatoria, such as the Wooroloo farm in Western Australia, which opened in 1914.[15] Although the farm at Greenvale did not have the longevity of other patient-run farms, it is significant because the work undertaken by patients is relatively well documented (in comparison to the published histories of other Victorian sanatoria) in public records that reflect how patients experienced institutional life at the time.[16]

The relatively large volume of historical sources about Greenvale Sanatorium available at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) and in newspapers are not without lacunae. For example, the annual reports released by the Office of the Government Statist and the Department of Public Health focus on the number of patients admitted or discharged in a given year, but do not mention therapeutic treatments. Letters to the editor and reports in Melbourne-based newspapers provide some insight into the experiences of visitors and patients at Greenvale, but were only published if there was broader public interest. These do not record daily minutiae. Some items held by PROV, including typescript testimony, provide a more granular description of the sanatorium’s day-to-day operations; however, in the case of the testimony, as these were recorded by the institution’s staff or other government employees, they reflect what those in charge considered important to document. Yet, despite such biases and limitations, these sources can be combined to give an imperfect but nuanced narrative regarding the development of the farm at Greenvale Sanatorium.

Labour and the sanatorium farm

Due to gaps in the records, it is not clear when structured, therapeutic labour was introduced as a treatment at Greenvale Sanatorium. As early as 1906, a year after the institution opened, a photograph album published by the Department of Public Health, titled Views of the Greenvale Sanatorium for consumptives, Victoria, may show the earliest known instance of patients working in the sanatorium grounds (Figure 2).[17] While it is obvious that the three figures dressed in characteristic white uniforms are nursing staff, it is impossible to determine if the four figures in dark clothing, holding rakes and working in the foreground are also staff, or patients.

Figure 2: ‘The Gresswell Wards’, photograph from Views of the Greenvale Sanatorium for consumptives, Victoria (1906). Reproduced with permission of the State Library of New South Wales, [Q725.5].

Definitive evidence that patients worked around the institution appeared a few years later in January 1909. The Argus reported that this work was undertaken outdoors in the ‘extensive grounds’ and fresh air of the rural sanatorium, ‘as directed by the Medical Superintendents’.[18] Male patients reportedly engaged in gentle exercise, gardening around the wards and attended religious services.[19] Female patients also worked out of doors, but specifically assisted with ‘domestic work … such as washing up’.[20] By May 1910, a ‘poultry plant’ had been constructed on the grounds, with a ‘good collection’ of chicken breeds selected for both egg laying and meat production.[21] With calls for more beds, and opportunities for the tuberculous to be ‘healthily engaged in agriculture’, the Greenvale Sanatorium soon expanded.[22] This was not an expansion in terms of its landholdings, but in terms of its ambition to use that land for farming.

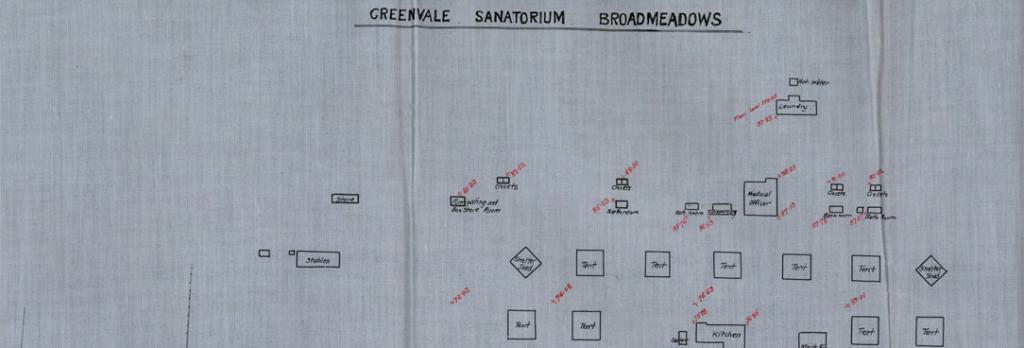

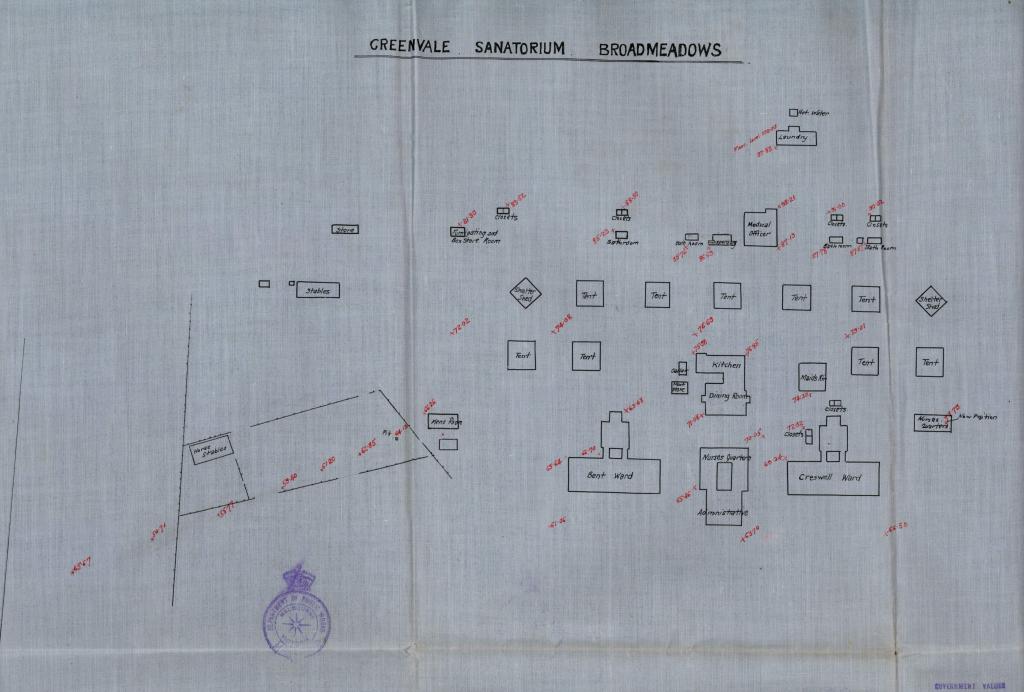

The small-scale poultry operation expanded into a model farm in less than two years, the result of the sanatorium’s landholdings increasing from 400 to 600 acres in March 1912. At the same time, the number of beds also increased from 70 to 90.[23] The sanatorium itself sprawled across 13 structures, comprising wards, ‘frame tents’ and chalets, and farm infrastructure (Figure 3).[24] Between 1913 and 1918, multiple newspaper reports provide a fuller picture of the scale and variety of work undertaken on the farm. By 1915, the area under cultivation was reported to include 14 acres of vegetable gardens; 60 acres of hay for fodder; paddocks and shelter for horses and dairy cows; and a flock of sheep for mutton.[25] In 1918, it was reported that the sanatorium farm grew cabbages, carrots, turnips and calabashes.[26] Patients were recorded labouring in the production of eggs, poultry, bacon, mutton, crops for use within the institution and, surprisingly, milk—although this appears to have been indirect labour due to the risk that tuberculous patients posed for cattle.[27]

Figure 3: An undated site plan of Greenvale Sanatorium, c. 1912–1929, showing how the patient facilities, including accommodation, kitchen and dining room, were clustered together. The stables were set apart from this central area. PROV, VPRS 16582/P1, GV 12/284, Greenvale – Sanitorium – 1912 to 1929, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/B9E49293-F869-11E9-AE98-47CDDAEDBDB8?image=1#>.

These records, which confirm that patients were contributing to the farm’s operation, can be compared to how different tasks were classified by the Department of Public Health in terms of their therapeutic benefit. Male and female patients sowed seeds and planted crops as therapeutic light work. Other agricultural and garden work was undertaken by patients, although ‘the hard work of ploughing’ was performed by paid farmhands.[28] Graded into four categories of difficulty, this therapeutic labour was used as a yardstick to measure patient recovery from active tuberculosis. As a patient’s health improved, and they could tolerate more strenuous work outdoors, a greater proportion of the tasks essential for running a farm were allocated to them. Even the weakest patient was expected to work outside ‘cutting off dead flowers’, as seen in Table 1.[29]

Table 1: The four grades of garden and agricultural work undertaken at Greenvale Sanatorium in 1912. Adapted from: Department of Health, Greenvale Sanatorium for consumptives (1912).

|

Grade of Work |

Garden and Agricultural Activities |

|

Grade 1 |

Cutting off dead flowers |

|

Grade 2 |

Carrying baskets of mould &c., for various gardening purposes, watering garden with small cans |

|

Grade 3 |

Using small spades in broken ground, hoeing, watering garden with larger cans, care of poultry, cleaning poultry-house, chopping light wood |

|

Grade 4 |

Using a large spade, wheelbarrow work in garden, planting and weeding in flower and vegetable garden, clearing land |

It is intriguing to note that the literature aimed at prospective patients denied that these tasks were a cost-saving measure. Further, unlike in Brown’s 1914 proposal, physical exercise was not associated with a new life after discharge—that is, the tasks did not come with the promise a new, more appropriate occupation outdoors upon recovery. Instead, the emphasis was on the therapeutic benefits such labour would provide as a part of a patient’s rehabilitation after active tuberculosis. A pamphlet produced by the Board of Health in 1912 explained that treatment at Greenvale included:

Special physical exercises … [that] have as their object the improvement of the general physique and of the lung capacity … The object [of these activities] is not to obtain cheap labour, but to harden the body gradually, in order that patients may be better able to engage without harm in their respective occupations after leaving the institution … Under such conditions, patients benefit, and they also learn to help themselves, as well as others, and so become fitted to return to the stress of ordinary life.[30]

In reality, patients were used as unpaid labour to reduce the geographically isolated sanatorium’s operating costs and to help make the institution self-sufficient, thereby enabling it to continue to admit and treat patients.

Alfred Austin Brown and his ‘great idea of having a farm colony’[31]

The expansion of the sanatorium’s agricultural landholdings and increase in the number of patients who could participate in labour as part of their treatment required experienced agricultural management combined with medical expertise. The medical superintendent who oversaw the site’s expansion from 1912 onwards, Alfred Austin Brown, possessed the required combination of skills.[32] He had completed a bachelor of medicine (1894) and a bachelor of surgery (1896) at the University of Melbourne, qualifying him as a medical practitioner. However, prior to his appointment at Greenvale, there is no record of him practising medicine.[33] Instead, he worked with the Department of Agriculture as a meat inspector, displaying a clear interest in farming, food hygiene and parasitology. Brown often answered questions from the general public about poultry raising and parasites in local newspapers.[34] Meat inspection became increasingly medicalised in the early twentieth century, and Brown’s office was eventually transferred to the Department of Public Health in 1911.[35] He became the medical superintendent of Greenvale the following year.

It appears that Brown’s longstanding interest in agriculture was a significant driver in the development of Greenvale’s landholdings. Beside his 1914 proposal, he was regularly quoted in the press proposing other schemes using tuberculous patients to operate farms. For example, he suggested that the government should acquire land for farming ‘somewhere along the Yarra’, Melbourne’s major waterway.[36] The aim of such a farm would be to train his patients in ‘a robust country occupation’ that could offer a future livelihood outside of polluted cities, while simultaneously producing goods to be sold.[37] In these hypothetical scenarios, the profits of such an enterprise were to be split between the Department of Public Health and the patient workers.[38] Such grandiose and seemingly altruistic plans were never realised; ultimately, Brown was only involved in the farm at Greenvale, which did not share its profits with patients. Six years after the Greenvale farm opened, Brown’s experiment was halted by a Royal Commission into the sanatorium’s management. Testimony provided to the Royal Commission comprises the most detailed, if indirect, source regarding the role of farm work in patient treatment.

The Royal Commission was assembled to investigate allegations relating to the provision of food for patients and embezzlement of goods by employees of the Board of Health. The alleged embezzlement included eggs ‘produced for the use of patients’ and ‘milk or cream’ that was sold or given away. Further, it was claimed that patients ‘were not supplied with sufficient poultry and vegetables’ at mealtimes despite having grown these foodstuffs themselves.

Although patients’ labour was integral to the production of food at Greenvale, the Royal Commission was primarily focused on the financial impact of the farm on the institution as a whole. Therefore, patients’ testimony was often redacted when they spoke at length about the types of activities they undertook as part of their therapy—whole pages were removed before the typescript testimony was bound. No published account of the Royal Commission has been found to date. Nevertheless, what remains of the surviving testimony provides unique insight into the farm’s operations in 1918, including how controversial it was to operate Greenvale as a farm in the first place.

Alison Bashford and others have used Greenvale as an example of how graduated labour was embraced in Australia.[39] However, by focusing on the economic impact of tuberculosis on society, and by only referring to sources intended to appeal to prospective patients, such studies inadvertently obscure the range of nuanced opinions held within the Department of Public Health at the time. The two most significant, and relevant, themes that emerge from the testimony of senior members of the department are: 1) criticisms regarding Brown’s approach to farm work as occupational therapy and 2) the existence of the Greenvale farm itself. Frederick William Hagelthorn, a former minister of public health, asserted that the farm, first developed as a poultry plant in 1910, should not have been further expanded. Hagelthorn told the Royal Commission that he ‘was not at all enthusiastic about it, and … tried to discourage [Brown] from going on with this work on land’, a sentiment that Brown corroborated in later testimony.[40]

According to Brown:I handed them [the livestock] all over [to the sanatorium]. I did that to train the patients in the various industries. At first the government would not assist me, in fact I was discountenanced from starting the farming operations, but inasmuch as I had a great idea of having a farm colony I started the industries for the patients. I put all the industries on the place myself, except a couple of cows … The progeny of the sheep I paid for originally … I handed it over to the institution, every penny.[41]

It is unclear what was behind Hagelthorn’s disapproval of agriculture for patient therapy. Certainly he was not the only critic. Another group who questioned the need to undertake farm work, although not included in the surviving Royal Commission testimony, were former patients. At least one former patient complained that patients were required ‘to undertake task work of an uncongenial character’ at the institution.[42] If any other patients had concerns about graduated labour during the Royal Commission, they either went unmentioned or, if they were recorded, were later excised from the testimony and have since been lost.

In contrast to Hagelthorn’s concerns, the current chairman of the Board of Health, Edward Robertson, who had been in the position since 1913, supported the farm project in his statement to the Royal Commission.[43] Robertson emphasised that the primary role of the farm was to reduce operating costs; its secondary purpose, as ‘a working exhibit’, was ‘to instruct patients who might take up that line of life after leaving the sanatorium’.[44] Curiously, this reasoning directly conflicts with public-facing literature produced by the Department of Public Health, which claimed that occupational therapy was not used ‘to obtain cheap labour’, despite the farm relying on patients’ therapeutic labour to produce the eggs, poultry and vegetables that were the focus of the Royal Commission.[45]

The scale of the sanatorium farm

Due to the Royal Commission’s focus on financial matters, the surviving testimony provides fresh insight into the role of hired farmhands. Dairying, in particular, was a large, labour-intense industry; the milk was used by the sanatorium and the cream was sold. However, the milk was not solely served to patients. According to the testimony of the farm overseer, approximately 5 gallons of milk per day was kept at the dairy for feeding pigs, poultry and calves.[46] Cattle work was performed by paid, non-tuberculous workers hired from outside the sanatorium. Such workers did not interact with patients.[47] At the time of the Royal Commission, the sanatorium kept 13 dairy cows that produced approximately 70 quarts (17.5 gallons) of milk per day.[48]

Aside from dairying, the other large farming enterprise at Greenvale that attracted the attention of the Royal Commission was poultry. Brown, in his capacity as superintendent, explained that the poultry yard was further developed from the original 1910 plant in 1915–1916, and that birds were sold to outside businesses ‘in order to make the institution a success, and pay for the cost of the [wheat] feed’ that the birds required.[49] As of October 1917, patients were overseeing the care of 10 geese with 20 goslings, 15 ducks with 60 ducklings, 181 unspecified fowl and 721 chickens.[50]

It is possible to suggest a likely location for the poultry yard on the property based on testimony and contemporary stocking rates. By the late nineteenth century, an Australian poultry farm with average soil fertility could be expected to hold up to 100 fowls per acre (approximately 247 fowls per hectare), hence the sanatorium’s 902 fowls and chickens could be accommodated across nine acres of pasture (3.6 hectares).[51] The southern area of the property could have been large enough to comfortably accommodate such a large number of birds, as the area had already been used for livestock, with paddocks and horse stables constructed prior to the property’s expansion in 1912.[52] Further, as patients could work in the poultry yard, it needed to be easily accessible from the sanatorium wards and chalets.

Although there is limited information about where farm infrastructure was located during this period, it is clear that the sanatorium site had been significantly altered. Unlike heavily forested, rural mountain sanatoria in the late nineteenth century in Australia and Europe, and Greenvale itself in the early twentieth century, the lands surrounding the patients’ wards did not provide a natural, forested barrier, isolating the tuberculous from the outside world.[53] Instead, large portions of the property were used by patients, and much of the land was cleared for farming. This was markedly different from the small-scale gardening undertaken by patients at contemporary charitable institutions, such as the Victorian Sanatorium for Consumptives, or the maintenance work undertaken at the Kalyra Sanatorium in South Australia.[54] Greenvale’s graduated tasks were much more extensive than the activities reported at other Australian sanatoria during this period.[55] The scale of the Greenvale institutional farm seems to be only comparable with sanatoria in the United Kingdom studied by Linda Bryder and Laura Newman.[56]

The end of the Greenvale Sanatorium

With the therapeutic benefits of graduated labour, particularly graduated farm labour, being emphasised in newspaper accounts about Greenvale, it is surprising that auto-inoculation was not mentioned in the surviving Royal Commission testimony. Given the prominence in the contemporary literature of therapeutic work as a justification for the development of sanatorium farms in the British Empire during this period, it is worth briefly examining the statements of members of the Department of Public Health who supported the farm, and their apparent rationale for using patient labour. Brown apparently saw the farm as retraining patients for future occupations on the land. He ‘wanted to indicate to the patients … that [farming] could be profitably conducted by them longer than inside industries’.[57] Edward Robertson’s testimony to the Royal Commission also stressed this educational intention.[58] But auto-inoculation itself was not explicitly mentioned as a motivating factor in running the farm.

Without auto-inoculation being explicitly mentioned as the scientific rationale for patient treatment at Greenvale, it appears that the Royal Commission, and the state government, were forced to consider the intrinsic value of the sanatorium farm entirely in terms of any financial benefits it could provide. Brown insisted that the profits generated by the farm, nominally constructed to reduce the operating costs of the sanatorium, covered the expenses of the farm itself.[59] But it did not produce an overall profit for the parent institution (see Table 2). The combined revenue of produce sales and patient payments were entirely consumed by the institution’s running costs, so the sanatorium itself never made an overall profit. In fact, in terms of revenue, the bulk of Greenvale’s income comprised fees paid by the Department of Defence for the treatment of tuberculous ex-servicemen.[60]

Table 2: Revenue from the sale of produce compared to annual income and the cost of running the sanatorium, rounded to the nearest pound. Source: PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index.

|

Year |

Gross cost (£) |

Revenue |

Nett cost (£) |

|

|

Sale of produce (£) |

Patient contributions (£) |

|||

|

1914–1915 |

4,650 |

354 |

97 |

4,199 |

|

1915–1916 |

4,758 |

458 |

164 |

4,136 |

|

1916–1917 |

4,707 |

471 |

432 |

3,804 |

|

1917–1918 |

4,332 |

434 |

82 |

3,817 |

At the close of the Royal Commission, the commissioners highlighted the steep financial cost of maintaining dairy cows and sheep at the hospital, which was seen as a needless expense. Brown’s stated goal of operating an educational training farm conflicted with the need for the institution to be run economically. Despite the Royal Commission concluding that there was no evidence of embezzlement, or other wrongdoing, it signalled the end of Greenvale’s large-scale farm project.[61] Five years after the sanatorium had procured dairy cattle and sheep, the farm was ordered by Premier John Bowser ‘to be abolished’.[62] Interestingly, and despite the order, it appears that farm work continued at the site, albeit sporadically, until the 1930s. Brief newspaper reports provide hints of the agricultural activities that continued there, including raising cattle for beef and growing vegetables for a Christmas dinner in 1920.[63] The dairy is also mentioned as late as 1924, suggesting that it continued to operate, albeit in unhygienic circumstances.[64] In the same year, the Department of Agriculture recommended that a farm manager be employed, implying that this had not been the case to that point, and that the farm was large enough to need oversight. This era definitively ended in 1938 when the farmland was leased to external dairy farmers to graze cows.[65]

It is possible that patients continued to labour at Greenvale after 1918, as farm work continued to be utilised in the rehabilitation of the tuberculous elsewhere in Australia. Training farms at Beelbangera (1920–1923) and Janefield (1920–1925), funded by the Australian Repatriation Department, aimed to educate former soldiers who had convalesced from tuberculosis, and were no longer infectious, in agricultural work, so they could be issued with a soldier settlement block to cultivate as yeomen farmers.[66] This unambiguous emphasis on retraining, rather than relying on the earlier auto-inoculation theory of graduated labour, was part of a wider trend in the repatriation of World War I veterans who had been incapacitated by their military service. These men were being rehabilitated through the power of labour, such as working in government workshops and factories to produce goods for sale.[67]

The therapies offered to patients at Greenvale after the farm closed remain unclear. The complaints of some former patients notwithstanding, it is apparent that some patients benefited from the farm scheme. For instance, David Grieve was treated at the sanatorium for 10 weeks, during which time he worked as a carter. When he was called up for the Royal Commission, he was successfully working as a bread carter in Dandenong.[68] However, other former patients who testified at the Royal Commission had returned to indoor work after discharge or could only find employment within the sanatorium itself.[69] Regrettably, the detailed work histories of patients during and after their discharge are not available.

Conclusions

Although historical records, such as the Royal Commission testimony, can provide a fuller and more nuanced picture of how the Greenvale Sanatorium operated in the early twentieth-century, there are still gaps in our knowledge of the farm.

One issue is the difficulty in mapping how the site changed as the farm grew. While site plans are available for Greenvale, they all predate or postdate the period when the farm operated. The Victorian Government’s systematic aerial photography of the state only started to regularly include the wider Greenvale area from 1951 onwards, after the farm closed.[70] This makes the Royal Commission testimony vital in interpreting how the sanatorium farm operated, and its sheer scale.

The size of the property, and the range of activities undertaken, do not appear to have limited the farm’s operations; although it remains unclear how much time per day was spent on farm work. Instead, it is likely that it was the use of tuberculous patients—who could only work for limited periods on a narrow range of activities, according to their health—that was the limiting factor. Hence, while the farm successfully produced enough food to cover the cost of paying for items such as seed, it could not ultimately sustain itself.

By analysing the role of farming as a therapeutic treatment at the Greenvale Sanatorium, it becomes apparent that the historiography of Australian sanatoria is more complex than previously thought. Today, the site of Greenvale Sanatorium, the first purpose-built, government-run sanatorium in Victoria, is split between the Woodlands Historic Park complex, a cemetery, the local council and private ownership. During its lifetime, Greenvale expanded to include large landholdings that could support onsite farming operations. It was successful enough, using patient and paid labour, to produce a surplus of goods, although it may never have been financially viable long term. It formed part of a therapeutic landscape that was deliberately designed to redefine and transform the tuberculous patients who worked the land, into skilled, productive members of society who could support themselves financially.[71]

This therapeutic landscape reflected the anxieties of wider society, and the need to control members of the working class considered to be dangerous and harbouring disease.[72] Despite its significance in Australian tuberculosis treatment history, and the popularity of graduated labour in Australia and overseas sanatoria, it does not appear that Brown’s project was well received by the Department of Public Health. Information directed towards the general public and prospective patients insisted that agricultural work was only undertaken for its therapeutic benefits. This, however, contrasted with testimony given at the Royal Commission that revealed that the farm was primarily seen by the Department of Public Health as a means to reduce the ongoing costs of operating the first public sanatorium in Victoria.

The use of tuberculous patient labour to produce agricultural produce at the farm at Greenvale predates the use of such labour at better known institutions, such as Wooroloo, Western Australia. When compared to contemporary sanatoria overseas, particularly those operating in the United Kingdom, the scale of work undertaken using patient labour was smaller, although, curiously, Greenvale’s rationale was not couched within the language of auto-inoculation theory.

That the chief medical officer of Greenvale, Alfred Austin Brown, was both a physician and an animal pathologist is significant in understanding how the sanatorium’s farm expanded to the extent seen in 1918. It is clear that Brown believed the farm would benefit not only his patients, but also the Department of Public Health. He used his skills and position to develop what may have been the first sanatorium farm to operate in Australia.

Endnotes

[1] Anonymous, ‘About people,’ Age, 16 October 1911, p. 6; Anonymous, ‘It is an indication for man’s Love …’, Freeman’s Journal, 1 October 1914, p. 37.

[2] Rebecca Le Get, ‘In the shadow of the tubercle: the work of Duncan Turner’, Health and History, vol. 20, no. 1, 2018, p. 74.

[3] Robin Walker, ‘The struggle against pulmonary tuberculosis in Australia, 1788–1950’, Historical Studies, vol. 20, no. 80, 1983, pp. 439–461.

[4] Alison Bashford, Imperial hygiene: a critical history of colonialism, nationalism, and public health, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004, p. 65.

[5] Bashford, Imperial hygiene, 64.

[6] Emily Webster, ‘Tubercular landscape: land use change and mycobacterium in Melbourne, Australia, 1837–1900’, Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 67, 2020, 48–60; Alison Bashford, ‘Tuberculosis & economy: public health & labour in the early welfare state’, Health and History, vol. 4, 2002, pp. 19–40.

[7] Julie Collins, ‘Life in the open air: place as a therapeutic and preventative instrument in Australia's early open-air tuberculosis sanatoria’, Fabrications, vol. 22, no. 2, 2012, p. 225.

[8] Anonymous, ‘Patients’ tasks: Greenvale Sanatorium’, Herald, 28 April 1913, p. 7.

[9] Linda Bryder, Below the magic mountain: a social history of tuberculosis in twentieth-century Britain, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1988.

[10] Ibid., 57; Marcus Paterson, Auto-inoculation in pulmonary tuberculosis, James Nisbet & Co. Ltd., London, 1911, pp. 28–29.

[11] Bashford, Imperial hygiene, 66.

[12] Flurin Condrau, ‘Urban tuberculosis patients and sanatorium treatment in the early twentieth century’, in Anne Borsay and Peter Shapeley (eds), Medicine, charity and mutual aid: the consumption of health and welfare in Britain, c. 1550–1960, Ashgate Historical Urban Studies, 2007, p. 198.

[13] Hospital Visitor, ‘Consumptive sanatorium’, Argus, 26 April 1905, p. 7.

[14] Anonymous, ‘Patients’ tasks: Greenvale Sanatorium’, Herald, 28 April 1913, p. 7.

[15] Anonymous, ‘Greenvale Sanatorium’, Ballarat Star, 29 April 1912, p. 6; ‘Assessment documentation: Wooroloo Sanatorium (fmr)’, Register of Heritage Places, Heritage Council of Western Australia, available at <http://inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au/Admin/api/file/a5020740-1d4c-ef52-953e-c3c3572ed567>, accessed 30 August 2018; Walker, ‘The struggle against pulmonary tuberculosis in Australia’.

[16] AJ Proust, History of tuberculosis in Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, Brolga Press, Canberra, 1991, pp.), 151–152.

[17] Department of Health, Views of the Greenvale Sanatorium for consumptives, Department of Health, Melbourne, 1906.

[18] Anonymous, ‘The cult of fresh air: Greenvale Sanatorium revisited’, Argus, 14 January 1909, p. 7.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Utility, ‘Poultry notes,’ Weekly Times, 14 May 1910, p. 50.

[22] Anonymous, ‘Intermediate consumptives: special provision needed’, Argus, 1 June 1910, p. 6.

[23] FW Mabbott, ‘Lands temporarily reserved from sale, etc.’, Victorian Government Gazette, 27 March 1912, p. 1335; Office of the Government Statist, Statistical register of the state of Victoria for the Year 1912. Part VI: social condition, Albert J. Mullett, Melbourne, 1913, p. 24.

[24] Office of the Government Statist, Statistical register of the state of Victoria for the year 1912. Part VI: social condition, 24.

[25] Anonymous, ‘Greenvale Sanatorium’, Ballarat Star, 29 April 1912, p. 6; MP Williams, ‘Consumptive sanatorium, Greenvale, re-visited’, Malvern News, 25 September 1915, p. 2.

[26] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, 1919, pp. 131, 133, 301, 312; Anonymous, ‘Horticulture’.

[27] Anonymous, ‘The Green Vale Sanatorium: an official inspection’, Age, 10 February 1913, p. 15; Anonymous, ‘Horticulture’, Weekly Times, 14 April 1917, p. 48; WH Edgar, ‘Greenvale Sanatorium’, Hansard, 27 November – 20 December 1918, p. 3126.

[28] MP Williams, ‘Consumptive sanatorium, Greenvale’.

[29] Department of Public Health, Greenvale Sanatorium for consumptives, 5th ed., J. Kemp, Melbourne, 1912, pp. 13–14.

[30] Ibid., p. 13.

[31] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, 1919, p. 686.

[32] Anonymous, ‘About people’.

[33] WA Callaway, ‘Medical Board of Victoria’, Victoria Government Gazette, 4 January 1895, p. 6; Anonymous, ‘Local subjects’, Australian Medical Journal, 20 January 1895, p. 47; Royal Commission on the Butter Industry, Minutes of Evidence and Appendix, Robt. S. Brain, Melbourne, 1905, p. 699.

[34] Wanalta, ‘Correspondence’, Leader, 11 December 1897, p. 20; Anonymous, ‘Answers to correspondents’, Australasian, 27 June 1903, p. 14.

[35] Keir Waddington, The bovine scourge: meat, tuberculosis and public health, 1850–1914, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2006), pp. 131-–152; PROV, VPRS 4402/P0, Volume 22, Public Service Board, Department Public Health Professional Register of Offices.

[36] AA Brown, ‘Farm Colony for Consumptives’, Medical Journal of Australia, 26 August 1916, p. 156.

[37] Ibid., p. 155.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Bashford, ‘Tuberculosis & economy’, pp. 26–27; Alison Bashford, ‘Cultures of confinement: tuberculosis, isolation and the sanatorium,’ in Alison Bashford and Carolyn Strange (eds), Isolation: places and practices of exclusion, Routledge, London, 2003, pp. 131–132.

[40] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, pp. 131, 133, 135.

[41] Ibid., p. 686.

[42] Anonymous, ‘Patients’ tasks: Greenvale Sanatorium’.

[43] EM Robertson, ‘Robertson, Edward (1870–1969)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/robertson-edward-8232/text14411>, accessed 5 April 2021.

[44] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, p. 326.

[45] Department of Health, Greenvale Sanatorium for consumptives, p. 13.

[46] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, p. 739.

[47] Ibid., p. 739; Edgar, ‘Greenvale Sanatorium’, p. 3126.

[48] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, pp. 409, 555.

[49] Ibid., pp. 682, 687, 759.

[50] Ibid., p. 759.

[51] AJ Compton, The Australasian book of poultry, George Robinson & Co, Melbourne, 1899, p. 7.

[52] PROV, VPRS 16582/P1, Greenvale – Sanitorium – 1912–1929.

[53] Rebecca Le Get, ‘A home among the gum trees: the Victorian sanatorium for consumptives, Echuca and Mount Macedon’, Landscape Research, 2018, p. 9.

[54] Collins, ‘Life in the open air’, p. 225; Le Get, ‘A home among the gum trees’, p. 9.

[55] Collins, ‘Life in the open air’, p. 225.

[56] Bryder, Below the magic mountain, pp. 54–67; Laura Newman, ‘Germs and the working-class body: redefining tuberculosis at the post office sanatorium society’, in Germs in the English Workplace, c.1880–1945, Routledge, New York, 2021.

[57] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, pp. 689–690.

[58] Ibid., p. 326.

[59] Ibid., p. 687.

[60] Ibid., p. 325.

[61] Anonymous, ‘Officers are exonerated in the Greenvale inquiry,’ Herald, 9 December 1918, p. 9.

[62] John Bowser, ‘Greenvale Sanatorium Commission’, Hansard, 27 November – 20 December 1918, p. 2645.

[63] Anonymous, ‘Christmas at Greenvale’, Argus, 29 December 1924, p. 6.

[64] Anonymous, ‘Greenvale Sanatorium: official’s scathing report’, Argus, 10 March 1924, p. 13.

[65] Ibid., p. 13.

[66] Walker, ‘The struggle against pulmonary tuberculosis in Australia’.

[67] Clem Lloyd and Jacqui Rees, The last shilling: a history of repatriation in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1994.

[68] PROV, VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 110, Greenvale Sanatorium Commission: evidence and index, p. 34.

[69] Ibid., pp. 136, 500.

[70] Land Victoria, Melbourne and metropolitan project no. 2 (1/1951), aerial photography, run 6, frame 132.

[71] Rodney Harrison, Shared landscapes: archaeologies of attachment and the pastoral industry in New South Wales, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2004, p. 10.

[72] Bashford, ‘Tuberculosis & economy’, p. 21.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples