Last updated:

‘The story of Mrs H, case number 35: a victim of smallpox or fear?’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 20, 2022. ISSN 1832-2522 Copyright © Meaghan McKee.

Sarah Hanks, a newly married 21-year-old woman, died in Walhalla, Victoria, during the 1868–1869 smallpox outbreak. In 2019, a lonely gravesite discovered in the vicinity of Walhalla was claimed as Sarah’s resting place. Doubts about the likelihood of the grave belonging to Sarah inspired the research for this article. While the investigation confirmed such doubts, it was Sarah’s diagnosis and treatment, as well as scholarly debates around the impact of smallpox versus chickenpox and the blame assigned to the Chinese population for the spread of diseases such as smallpox, that proved most interesting. It appears that the effect of chickenpox on the colonial Australian population has been misrepresented. By looking at a wide range of sources, such as local recollections from the time, news articles, public records and the chief medical officer’s correspondence, a clearer picture emerges of the fear and notoriety that came with a smallpox diagnosis in colonial Victoria.

The historic town of Walhalla is a popular and picturesque destination for day trippers and campers. Located in a steep valley in the Great Dividing Range south-east of Melbourne, Walhalla, today, is an echo of its former self, its glory days having occurred in the late 1800s when the region enjoyed a short but prosperous gold rush. Just north of the town is a steep walking trail that leads to a unique cricket ground situated on a flattened hilltop. A lonely grave rests beside the trail with a sign that provides the visitor with a short history of an outbreak of smallpox in Victoria from 1868 to 1869. The sign states, ‘this is believed to be the grave of Sarah Hanks who died in Walhalla on March 23rd, 1869’, followed by an account of poor Sarah’s short time in Walhalla and a gruesome picture of a smallpox victim. The words ‘this is believed’ draws the reader to speculate. Believed by whom? Most people will pass by the grave with a brief thought for Sarah, then move on. But who was Sarah Hanks before her life ended so tragically? The sign describes a town that reacted—as was typical of the time—with fear at the news of Sarah’s illness. The townspeople were in a frenzy over the possibility that smallpox had come to Walhalla and the hysteria surrounding Sarah’s illness created misinformation that continues to this day.

Figure 1: Sarah Hanks information sign, Walhalla Cricket Club (2018). Photograph: M McKee personal collection.

The bushland on the steep hill beneath the cricket ground was burnt out during the February 2019 fires. In the subsequent clean-up, a volunteer claimed to have found the grave of Sarah Hanks in the form of a pile of rocks in a cleared area.[1] Within a few months, the possible grave was tidied up, a sign erected, a religious ceremony held and media articles written about the rediscovery of the grave of Sarah Hanks, the lady who brought smallpox to Walhalla.[2]

Conversation followed among local history experts about the likelihood of the site being Sarah’s grave; doubts were expressed because the location did not meet with some of the recollections passed down from the era. The uncertainty of the grave site prompted the research that led to this article. Many of the recent publications that mention the story of Sarah Hanks use the same two primary sources: a book by long-time Walhalla resident Henry Tisdall (1836–1905), and a news article published in 1869 by a local correspondent who wrote for the Gippsland Times.[3] Both describe the newly married Sarah arriving at Walhalla with her husband William and a son from William’s previous marriage. Within a few days Sarah became unwell and was diagnosed as having smallpox by the local doctor, Henry Hadden.

According to Tisdall and the correspondent, the heroic and decisive actions by the doctor and local authorities saved the town from an outbreak of smallpox. However, both narratives deviate in parts from what is in the public record, leading one to question whether Sarah had smallpox. Such doubts align with broader disagreements among Melbourne’s medical fraternity over other smallpox cases in Melbourne in 1868–1869. Indeed, the prevailing opinion of historians is that, throughout Australian colonial history, many smallpox cases were likely to have been chickenpox. Sarah may have simply been a victim of bad timing. The people of Walhalla had suffered the devastation of several contagions in the town and were no doubt nervous of any new disease entering the settlement. Whatever affliction Sarah Hanks had, it is certain she experienced a painful death in an unfamiliar place while suffering the indignity of being the talk of the town in her final days. Is it fair, then, that today Sarah is once again known as the woman who brought smallpox to Walhalla?

Sarah Hanks was one of 43 people who were reported to have contracted smallpox in Melbourne between 1868 and 1869.[4] Chief Medical Officer William McRea was able to determine that the outbreak originated from a ship’s crewman who arrived in Melbourne in November 1868.[5] Chief Mate William Webster brought the disease ashore from the barque Avondale that anchored in Hobsons Bay on 22 November 1868. The Avondale had departed the port of Foo Chow Foo on 2 September with a brief stopover at the Indonesian port of Anyar. Captained by William Ogilvie, the ship carried Ogilvie’s wife and family and a small crew, as well as chests and half chests of tea.[6] Foo Chow Foo was the anglicised version of the port of Fuzhou in the Fujian province of China.[7]

Webster was admitted to the Melbourne General Hospital, located on the corner of Swanston and Lonsdale streets, two days after the Avonlea arrived. According to McRea, medical experts at the hospital were not convinced that Webster was suffering from smallpox as his symptoms did not fit with those usually associated with the virus.[8] Webster was treated at the hospital and then moved to a residence in Bourke Street West that had been converted to a temporary hospital. Sadly, on 8 December 1868 Webster died. McRea and Town Clerk EG Fitzgibbon were alarmed that the patient had been moved to the residence. They had good reason to be worried, as an outbreak was detected soon after in nearby Shamrock Alley, a densely populated poorer area off Bourke Street.[9]

Figure 2: Melbourne General Hospital, 1860. State Library Victoria, Pictures Collection, image no. b20032.

Meanwhile, William Bessell, who had shared a room with Webster, also contracted the disease and was moved to the Immigration Hospital near Little Bourke Street. Several outbreaks occurred in the streets surrounding the Immigration Hospital and cases were soon appearing in houses in Little Bourke Street and Shamrock Alley.[10] The chief secretary wrote to the chief medical officer suggesting that patients be moved to an isolated building in Royal Park, but McRea replied that the existing premises were quite suitable.[11]

McRea requested that all doctors in Victoria advise him of cases showing symptoms of smallpox. As cases appeared, there followed some disagreement among doctors as to whether the outbreak was, in fact, chickenpox (varicella) rather than smallpox (variola).[12] At the time it was not possible to identify the difference pathologically and diagnosis was based on the observation of symptoms. Hunter and Carmody suggest in their 2015 paper, ‘Estimating the Aboriginal population in early colonial Australia: the role of chickenpox reconsidered’, that many smallpox cases reported in colonial Australia may have been chickenpox. Chickenpox is far more contagious than smallpox (up to five times) and provides a reasonable explanation for the rapid transmission of the disease through remote populations, particularly indigenous communities.[13]

McRea took a cautious approach to the 1868 Melbourne outbreak; even though some of the patients who contracted the disease had previously been vaccinated for smallpox, and even though there was a known outbreak of chickenpox in Melbourne at the time, McRea knew that, regardless of whether it was chickenpox or smallpox, it was dangerous. Chickenpox in the nineteenth century was a nasty disease to contract, particularly for adults.

The 43 cases that occurred from November 1868 to June 1869 were mostly located in the Bourke Street area around the Immigration Hospital. One boy was responsible for taking the virus to Greensborough, resulting in around 12 cases, but it was successfully contained.[14] Another case appeared at Tarnagulla near Bendigo but did not spread any further. By the early months of 1869, after a dry summer, McCrae had formed the opinion that a good downpour of rain would help flush the virus away from built-up areas. He also believed that a strong effort to re-vaccinate the public would help contain the outbreak.[15]

After the outbreak ended in June 1869, an enquiry was held to determine whether the 43 cases were all smallpox, a variant of smallpox or chickenpox, but no consensus was reached. An article in the 1869 Medical Journal of Australia stated that there was ‘an inordinate craving of notoriety’ when it came to announcements of smallpox outbreaks.[16] This may have been a factor in the case of Sarah Hanks.

Blissfully unaware of the outbreak, 22-year-old Sarah Jones married 24-year-old William Hanks on 19 February 1869 at St Marks Church of England in George Street Fitzroy.[17] Sarah’s early life appears uneventful. She was born Sarah Ann Jones on 18 August 1846 to William and Janette Jones (née Buchannan) in the parish of St James, Bourke County, Melbourne.[18] Her parents had married the year before she was born. The spelling of ‘Jones’ as ‘Sones’ in the births, deaths and marriages indexes causes confusion, but the consistent appearance of Janette Buchannan on all certificates provides confirmation of these details.[19]

In 1867, aged 21, Sarah was boarding in a house on La Trobe Street East, probably for work purposes.[20] She met William in the Fitzroy area and they married in a church near her parents’ home. William was a miner from Walhalla; according to news reports, he had had a lucky escape the previous October when an empty bucket fell down a shaft and hit him on the back.[21]

On their marriage certificate William and Sarah both stated their places of residence as Fitzroy, although William put his usual residence as Stringers Creek. Both were literate and able to sign their names. The witnesses were Jane Jones and Henry Frise. Both sets of parents were in attendance for the happy day. William’s parents were listed as Job and Elizabeth Hanks (née Cooper); Job worked as a mason.[22]

On 8 March, 17 days after their marriage, the young couple commenced the long journey to Walhalla, stopping at Shady Creek on the way. Gippsland was covered in thick, dense scrub at the time and the journey to Walhalla was long and arduous. The first part of the journey was by coach and the remaining section was on horseback. The couple would have been exhausted upon their arrival on 10 March. McRea stated that Sarah did not show symptoms until five days after her arrival in Walhalla.[23] She may well have felt fine during the incubation period. As they celebrated their honeymoon at Walhalla’s Grand Junction Hotel, the couple would have been unaware that Sarah was carrying the virus.[24]

Factoring in the boy’s incubation period, Sarah was likely to have been exposed between 27 February and 2 March. Her infectious period commenced either a day before the rash appeared or as soon as the rash appeared on 15 March. Given this, it is remarkable that no-one else was exposed to the virus.

Sarah saw the local medical man Henry Hadden on the day her rash appeared. Hadden claimed he had witnessed smallpox in his native Ireland and so diagnosed the lesions as smallpox.[25] For reasons unknown, it was not until the following day that Hadden asked his partner Dr Boone to confirm the diagnosis, which he did, and the diagnosis was then reported to the magistrate.[26] Sarah Hanks is known as ‘Mrs. H case number 35’ in McRea’s report. In the report, McRea stated that ‘Mrs. H’ had been residing at La Trobe Street East, Melbourne. He believed this was where she was likely exposed to the virus, as a young boy who lived two doors away displayed symptoms on 12 March and died on 20 March.[27]

In 1869 the goldmining town of Walhalla was a small but densely populated settlement of approximately 700 inhabitants located at the bottom of a steep valley. The settlement was still quite young. Ned Stringer had discovered alluvial gold in a nearby creek in 1863, and gold was found at Cohen’s Reef soon after, bringing an influx of people. Prior to the use of rainwater tanks, the residents had sourced their water from Stringers Creek. By 1869 the creek had become heavily polluted, and the townsfolk had experienced cholera and various respiratory and gastric diseases.[28] It is understandable that the people of Walhalla would have been nervous about any new diseases arriving in the town.

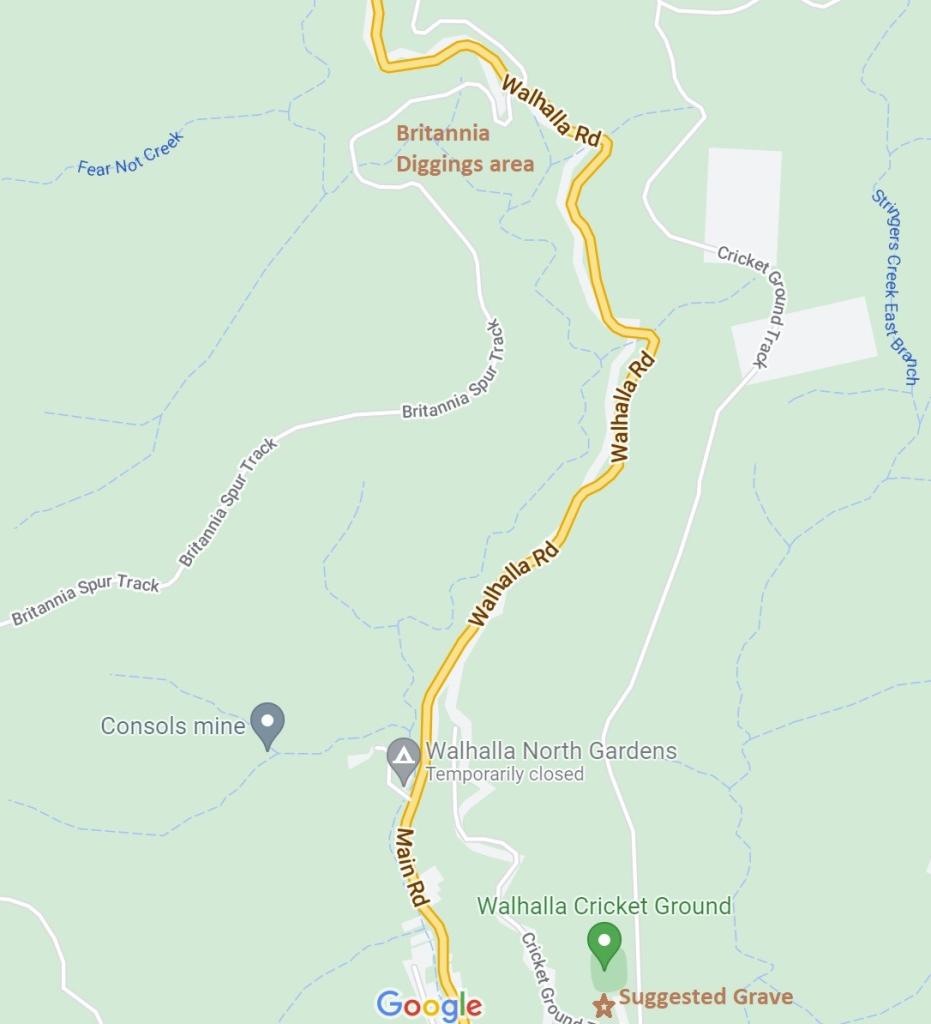

The news that smallpox was present sent the local town leaders into action. The magistrates placed the Grand Junction Hotel under police guard. Local police were also dispatched to find a house isolated enough to use as a small pox hospital. The recently deserted Britannia diggings north of town were considered suitable.[29] The diggings were isolated and empty with several buildings still in good repair.

Figure 3: Google map showing Britannia diggings (top) and suggested grave (bottom), 2022.

On Wednesday 17 March, Mine Warden Foster arrived at Walhalla. Mining wardens had a high level of judicial authority across the goldfields of Victoria.[30] Foster’s role was to keep the government informed of how the mining town was handling the outbreak. Meanwhile, William steadfastly refused to allow the authorities to take Sarah to the Britannia diggings. He must have been worried that Sarah would be forcibly removed, so, during the night, the couple escaped through the window of their hotel room to William’s own cottage. William’s cottage was located on a quarter-acre allotment in the centre of town on the left-hand branch of Stringers Creek.[31] This action placed all the residents of Walhalla at risk of exposure.

Hadden went to the hotel to visit Sarah on Thursday morning only to discover that the newlyweds had absconded. Local miners were furious with the landlord, John Parry, and had to be restrained lest they damage his hotel. The couple were soon discovered in William’s cottage. The magistrate ordered that the premises be placed into quarantine and an 8-foot paling fence be erected around the perimeter with a police guard. Two small sheds were erected at the end of the allotment, one inside and one outside the fence. If anyone was brave enough to visit to provide supplies or aid, they could enter one shed, strip off their clothes and step through to the next shed and change into clean clothes stowed there. The process would then be repeated on the way out. The disinfectant of choice at the time was carbolic acid, which was used liberally.[32]

William attempted to look after his wife without assistance but after a few days she became so unwell that a nurse had to be sought. Sarah’s condition had worsened so much that her screams could be heard around the vicinity of the cottage.[33] Mary Kybred, a local, elderly widow who spent her time fossicking for gold, was selected to be Sarah’s nurse. An illiterate cockney woman, she had worked in London hospitals before immigrating to Australia. Her nine-year-old grandson, John Buchanan, took clothes back and forth to the premises in a pillowcase to be laundered and disinfected by his mother.[34] Versions of Sarah’s story often refer to William having an older son from a previous relationship.[35] However, no son or previous marriage is mentioned in William’s records. Perhaps nurse Kybred’s young grandson was mistaken by some as belonging to William?

Sarah died on Tuesday 23 March 1869, eight days after her symptoms appeared. Boone signed her death certificate, which was witnessed by William Callow, the undertaker.[36] William and Sarah were only married for a few weeks. Alexander Bell, Esq., JP, at once convened a meeting of the men of the town to consider the next steps.[37] Sarah was to be buried the following day on 24 March; however, no-one was willing to carry the body through Walhalla. After lengthy discussion, four men agreed to carry the corpse to a grave on the crest of a steep hill a good distance north of the town. Callow supervised Sarah’s burial, after which the pall bearers bathed and changed outfits.[38] A strong picket fence was placed around the deep grave to keep people away. Possibly due to the haste and confusion surrounding Sarah’s burial, some of the information entered on her death certificate by the doctor and undertaker was incorrect, further adding to the indignity of her demise.[39]

On the same day Sarah was buried, the Hanks’s cottage was burned to the ground. William and nurse Kybred were taken to the Britannia diggings and placed in strict quarantine under police control for a further six weeks. The committee agreed to give William 75 pounds and build him a new home; Mary Kybred was given a 20-pound ticket to sail to Tasmania as payment.[40]

The spread of alarm through the town was typical of the time. Nicola Cousen’s 2018 Provenance article, ‘The smallpox on Ballarat’ highlights a similar reaction from 10 years previously. For example, in 1858, eight-year-old Miss Lecki was diagnosed first with chickenpox, then smallpox and later cowpox. The Star newspaper went to great lengths to discredit the cowpox diagnosis, which had been made by doctors at Ballarat Hospital, warning the public that an outbreak of smallpox was imminent and demanding that schoolchildren be kept at home. Thankfully, the public placed its trust in the hospital’s doctors or else the Star may have succeeded in its campaign to have the girl’s home destroyed.[41]

Walhalla’s resident newspaper correspondent pursued a similarly alarmist approach. According to his article published on 30 March 1869 in the Gippsland Times, all residents were asked to get themselves vaccinated and carbolic acid was distributed to all who needed it. Further, all Chinese residents were compulsorily ordered to attend the office of the government vaccinator.[42] It appears that the Chinese residents, although not to blame for the outbreak, were considered a risk simply because of their race. The local correspondent’s opinion of Walhalla’s Chinese residents was made clear in a subsequent article in which he warned of the risk of smallpox spreading through the local Chinese population who were ‘clean, so far as regards frequently washing themselves, and the use of the bath, yet they are by no means careful in either their garments or in their huts’. The correspondent pointed out that Boone had raised similar fears about the Chinese population at the Bendigo goldfields in 1855. Apparently Boone had requested that the Chinese be compelled to take the vaccination but had been advised by the chief medical officer that this would be illegal. The correspondent strongly suggested that the matter of compulsory vaccination of the Chinese be reconsidered.[43] There is no firm evidence that Chinese residents were compulsorily vaccinated at Walhalla in March 1869.[44] Regardless, singling them out in this way illustrates the suspicion held by many towards them at the time.[45] Fear of smallpox was widely used by newspapers to promote discrimination against the Chinese population even though smallpox was present in Australia before their arrival.[46]

Figure 4: ‘Out you go, John! You and your smallpox’, Illustrated Sydney News, 1881, State Library New South Wales.

The other doctor in town, Henry Hadden, had trained as an apothecary in Ireland and emigrated to Australia in 1853. Hadden was soon practising as a doctor on the goldfields near Castlemaine at Daisy Hill.[47] In 1855 he was convicted of neglect and manslaughter and sentenced to three years hard labour after a mother and baby had died during childbirth under his care. A news article on the court case referred to Hadden as a ‘medical man’ rather than a doctor. It was reported that he had attended the woman during her labour and, after becoming extremely drunk, had fallen asleep next to her.[48] Two medical witnesses later found the mother with the deceased baby still in the womb. The mother died soon after.[49]

Hadden was registered as prisoner 2,738 but disappeared from the Castlemaine area.[50] He reappeared in Walhalla in 1866 still practising medicine and still regularly intoxicated. A few months after the death of Sarah Hanks, Hadden died while travelling by coach to Walhalla on 29 May 1869. The inquest detailed that he had boarded the coach in a very intoxicated state and soon fell asleep. After a time, his fellow travellers became concerned and discovered that he had died. No signs of violence were found and the cause of death was recorded as unknown.

Walhalla’s local correspondent was incredulous at the outcome of the inquest for such a ‘dear friend’ as Hadden. In numerous articles over the following weeks, he tried to raise suspicion about the circumstances of Hadden’s death, even suggesting that he was poisoned. The matter did not go any further and Hadden now rests at Shady Creek in another lonely grave. Boone relocated to the Bendigo area soon after and is recorded as being buried at Donald, having died there in December 1877.[51]

The 2019 discovery of the possible grave of Sarah Hanks brought her story back into public view. The grave in question rests beside a track to a sporting ground that commenced construction two years after Sarah died.[52] Curiously, the sign that claims the grave is Sarah’s features a 2018 copyright date, earlier than the discovery of the site in 2019.[53] The location of the new grave does not quite tally with the description by the local correspondent in the Gippsland Times nor with the note in the book Lonely Graves of Gippsland that locates it near the Britannia Reef.[54] The choice of the Britannia Reef area for Sarah’s burial seems likely, as the Britannia diggings were located 3 km north of the town.[55] The diggings, which had been abandoned several months earlier, were located far enough away from the population to be a safe quarantine and burial area. A 1915 recollection of a previous resident stated the original grave sat on a zigzag track on the way to the cricket ground heading left towards the gully.[56] This gives some credibility to the newly proposed gravesite, but the track would not have existed in 1869 because the levelled cricket ground did not exist. News of the rediscovered grave appeared on television and in print and social media, bringing to mind a comment from the 1869 enquiry that perhaps ‘an inordinate craving of notoriety’ still exists around smallpox. ‘The woman who brought chickenpox to Walhalla’ doesn’t have the same impact as ‘the woman who brought smallpox’. With doubts about the new grave in mind, a simple solution would be to undertake a geophysics scan to verify whether the site is, in fact, a grave. The cost of the service could be recovered through a grant.[57]

It is important when we research historical events to take the time to investigate beyond one or two sources. Official public records provide an impartial view of historic events compared to personal recollections or local newspaper reports; however, all these sources are important to get a view of both facts and opinions. We now live in an era in which a story can enter the public arena with very little fact checking. News is spread across electronic media at breathtaking speed. The conflicting information about our current COVID-19 pandemic dwarfs the discussion around smallpox versus chickenpox in nineteenth-century Victoria. This shows that, in future, our public records will be even more vital to sift fact from fiction. In the meantime, it is good practice to question what we are told and investigate stories such as Sarah Hanks’s. By doing so, we provide a voice to those who are no longer able to speak.

Endnotes

[1] Walhalla Cricket Club, ‘Over the last couple of days we have visited the…’ [Facebook status], 12 February 2019, available at <https://www.facebook.com/Walhalla-Cricket-Club-628294650902811/?ref=page_internal>, accessed 1 May 2021.

[2] S Butler, ‘Respect for Sarah’, Warragul and Drouin Gazette, 26 March 2019, p. 35.

[3] HT Tisdall, A tale of old Walhalla: how we fought the smallpox in Walhalla, Moe: Walhalla Heritage League Inc, no date; ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869, p. 3.

[4] D Evans, Vaccine lymph: some difficulties with logistics in colonial Victoria, 1854–1874, in J Pearn & C. O’Carrigan (eds), Australia's quest for colonial health: some influences on early health and medicine in Australia, Brisbane: Department of Child Health, Royal Children's Hospital, 1983, p. 167.

[5] Victorian Government, Copy of correspondence relating to the recent introduction of small pox into the colony and the steps taken to arrest its progress VPARL1869NoA5, Melbourne: John Ferres Government Printer, 1869, p. 2.

[6] ‘Shipping’, Australasian. 28 November 1869, p.14.

[7] China Internet Information Centre, Fuzhou, available at <http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/43570.htm>, accessed 24 May 2022.

[8] Victorian Government, Copy of correspondence.

[9] Ibid., p. 2.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., p. 3.

[12] ‘The smallpox’, Argus, 9 April 1869, p. 7; Victorian Government, Copy of correspondence, p. 2.

[13] BH Hunter & J Carmody, ‘Estimating the Aboriginal population in early colonial Australia: the role of chickenpox reconsidered’, Australian Economic History Review, vol. 55, no. 2, 2015, pp. 112–138, doi:org/10.1111/aehr.12068.

[14] ‘Report by the Chief Medical Officer on the outbreak of smallpox in 1868–69’, in Central Board of Health, Twelfth report with appendices, Melbourne: John Ferres Government Printer, 1871, p. 28.

[15] Chief Medical Officer, Smallpox. An additional report of the Chief Medical Officer VPARL1869NoA14, Melbourne: John Ferres Government Printer, 13 April 1869, p. 3.

[16] ‘Variola or varicella’, Australian Medical Journal, January 1869, p. 27.

[17] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, William Hanks and Sarah Ann Jones, marriage registration no.1303, 1869.

[18] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, Sarah Sones, birth registration no. 14925, 1846.

[19] Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages Victoria, William Sones and Janette Buchannan, marriage registration no. 4977, 1845.

[20] Chief Medical Officer, Smallpox. An additional report, p. 2.

[21] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Guardian, 15 October 1868, p. 3.

[22] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, William Hanks and Sarah Ann Jones, marriage registration no.1303.

[23] Chief Medical Officer, Smallpox. An additional report, p. 2.

[24] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869, p. 3; Tisdall, A tale of old Walhalla.

[25] Tisdall, A tale of old Walhalla.

[26] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869.

[27] Chief Medical Officer, Smallpox. An additional report, p. 2.

[28] Y Reynolds, Walhalla graveyard to cemetery, Trafalgar: Genepool publishing, 2007, p. 5.

[29] R Paoletti, Walhalla adventurer tourist and 4wd map, 2013.

[30] EM Poletto, ‘Role of the mining warden Victoria’, Australian Resources and Energy Law Journal, vol. 26, no. 4, 2007, p. 358.

[31] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869.

[32] Tisdall, A tale of old Walhalla.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Reynolds, Walhalla graveyard to cemetery, p. 14.

[35] Butler, ‘Respect for Sarah’.

[36] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, Sarah Hanks, death registration no. 5661, 1869.

[37] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869.

[38] JG Rogers & N Helyar, Lonely graves of the Gippsland goldfields and Greater Gippsland, Bairnsdale: E-Gee Printers Pty Ltd, 1994, p. 53.

[39] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, Sarah Hanks, death registration no. 5661.

[40] Tisdall, A tale of old Walhalla.

[41] Nicola Cousen, ‘“The smallpox on Ballarat”: nineteenth-century public vaccination on the Victorian goldfields’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 16, 2018.

[42] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869.

[43] ‘Walhalla’. Gippsland Times, 10 April 1869, p. 3.

[44] PROV, VA 2889, Registrar-General’s Department, VPRS 3654 Registers of Vaccinations, 1857–1932, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/VPRS3654/records>.

[45] Ibid.

[46] I Welch, ‘Demonising the Chinese: the pathology of cultural difference 1855-1906’, in I Welch, Alien son: the life and times of Cheok Hong Cheong 1851–1928, Canberra: Australia: Department of Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University, 2003, p. 201.

[47] Reynolds, Walhalla graveyard to cemetery, p. 13.

[48] ‘Castlemaine Criminal Sessions’, Mount Alexander Mail, 14 December 1855, p. 5.

[49] PROV, VA 2889, Registrar General’s Department 1856–1873, VPRS 3654 Inquest Deposition Files, 1855/91 Female Ellen Kirkham Inquest <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/06C43152-F1BB-11E9-AE98-A156BCFCCAA2#>.

[50] PROV, VA 475, Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 515/P0000 Central Register for Male Prisoners 2067–2823 (1854–1856) William Henry Hadden Volume: 4; Page: 672; Prisoner number: 2738 <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/1C92B55C-F3A9-11E9-AE98-799611476606?image=690>.

[51] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, James Boone, death registration no.7809, 1869.

[52] G Butler, Walhalla Heritage Review. Melbourne: Graeme Butler and Associates, 2013, p. 274.

[53] Walhalla Cricket Club, sign for Sarah Hanks grave.

[54] ‘Walhalla’, Gippsland Times, 30 March 1869; Rogers &Helyar, Lonely graves.

[55] J Aldersea & B Hood, Walhalla valley of gold, Drouin: DCP Group, 2016, p. 143.

[56] Reynolds, Walhalla graveyard to cemetery, pp. 14–15.

[57] Hunter Geophysics, Unmarked grave detection, GPR-SLICE software, space weather forecasting, and camera sales, no date, available at <https://www.huntergeophysics.com/unmarked-grave-detection/>, accessed 12 March 2022.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples