Last updated:

‘The Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area, Geelong: who was Armstrong?’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 22, 2025. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Ann Hodgkinson.

A major new residential development to the south-west of Geelong, the Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area, is located on an old pastoral run licenced to John Armstrong. While his name is permanently inscribed in this development, the history of John Armstrong and his family is less well known. Early squatter occupations throughout Victoria were often poorly recorded. In this article, the historic maps collection at Public Record Office Victoria, together with a variety of other official and informal sources, is used to document Armstrong’s history and to identify his early land holdings, which stretched well beyond that of the current growth area. Arriving as a bounty immigrant shepherd, John Armstrong became first a valued overseer, then a large pastoralist with leases throughout Victoria, before finally becoming a respected landowner and emerging community leader. He lay the foundations that allowed his 12 children to also become prosperous graziers and community leaders in various parts of the country.

I first encountered John Armstrong while researching a project on the people who worked for the so-called ‘Lady Squatters’, Anne Drysdale and Caroline Newcomb, at their property, Boronggoop, in the vicinity of South Geelong. The Armstrong family left Drysdale and Newcomb’s employ at Christmas 1844 to take up their own depasturing license across the Barwon River at a property located on part of what is now the Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area. As a resident of the south-west coast of Victoria, I regularly travelled through this area on the way to Geelong, watching the housing estates grow seemingly overnight. This piqued my curiosity to explore the area further, particularly along the course of Armstrong Creek. I soon discovered the beautiful Warralily wetlands, the peaceful natural Dooliebeal Reserve and the old Stuart pathway. On one trip, I found Armstrong Grove, a suburb to be established on the site of the old Armstrong homestead but then still pastoral land. This was land that Armstrong purchased as freehold in 1853. But how much land, I wondered, had he occupied under his old pastoral lease? And what became of the family after they left Boronggoop? This article provides the results of my efforts to explore these questions. However, as always in historical studies, there are still aspects from this period left unanswered and requiring further research and analysis.

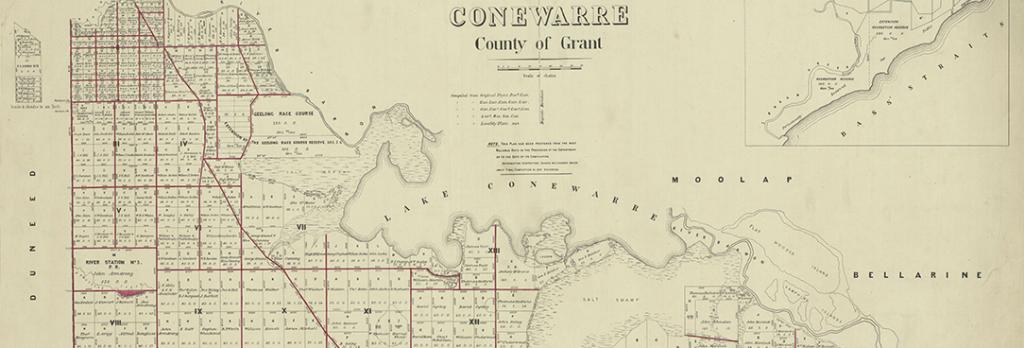

Located to the south of Geelong and straddling the Surf Coast Highway, Armstrong Creek is the largest contiguous urban growth area in Victoria. It covers 2,500 hectares of developable land and is expected to provide 22,000 residential buildings housing 55,000–65,000 people.[1] Gazetted in 2008, the Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area offered the City of Greater Geelong Council an opportunity to concentrate future urban growth in Geelong, Victoria’s second-largest city, into one area rather than allowing uncontrolled urban sprawl. Its location also provided an attractive housing alternative to the burgeoning northern and western suburbs of Melbourne. This growth was to be guided by sustainable planning principles, which included creating a sense of place by emphasising the natural environment, focal points of interest, design quality and public art (Figure 1).[2]

Figure 1: Plan of Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area showing the main districts (detail), appendix C from Greater Geelong City Council Minutes of Ordinary Meeting 9 August 2011. PROV, VPRS 17888/P1, LA/12/3218, Land Management – Place Names – Geographic Place Names – Naming Proposals – Armstrong Creek.

The wetlands on Warralily Boulevard where Armstrong Creek enters Lake Connewarre provide an excellent example of these characteristics. However, an understanding of the history of an area is an integral component in giving residents a sense of place and connection to their new home. As new residents admire this beautiful area, do they wonder why the entire urban growth area was named for this waterway? Do they wonder: Who was the person whose name is now permanently etched into Geelong’s urban fabric? Who was Armstrong?

The name Armstrong Creek commemorates the waterway that runs from Mount Duneed to Lake Connewarre. It was named for the pioneering Armstrong family that leased the majority of land within the old parishes of Mount Duneed and Conewarre (now called Connewarre). The entire urban growth area was named for Armstrong Creek in recognition of the family’s presence in the area. In 2012, the growth plan was amended to include two new localities, Armstrong Creek and Charlemont, with the first reflecting its early history. Charlemont was named for a ship, the Earl of Charlemont, that was wrecked off 13th Beach, Barwon Heads, in 1853. Survivors took a route along what is now Charlemont Road to reach Geelong.[3]

John Armstrong arrived in the colony that was to become Victoria in November 1839 on the Palmyra as a bounty immigrant with his occupation listed as shepherd. He was accompanied by his wife and five children aged from 2 to 10. A sixth child, Peter Brown Palmyra, was born on the voyage.[4] From this humble beginning, Armstrong would prosper to become one of the most respected sheep masters in the colony. He was one of the first to adopt the dipping method to cure scab and other insect pests. He and his children became large landowners and graziers with properties throughout Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland. This success was a consequence of his own farming skills, hard work and a fortuitus, mutually beneficial connection with the renowned ‘lady squatters’, Anne Drysdale and Caroline Newcomb.

The Armstrong family came from Buccleuch in the Scottish borders, a small rural area south-west of Selkirk. The area is associated with the ‘Duke of Buccleuch’, the Scott family seat and the novelist Sir Walter Scott. It was good sheep country. John’s wife, Veronica Scott, known as Vair, had family connections in the area. John brought to the colony an excellent knowledge of sheep husbandry that he adapted to the new conditions. Anne Drysdale’s diaries record almost daily entries on the Armstrong family’s activities up to the time when they obtained their own property. The family were initially employed by George Read near Meredith, where their eldest son, William, also worked as a shepherd.

Anne Drysdale also arrived at Port Phillip in 1839 from Scotland. She obtained a licence for a 10,000-acre property south of Geelong called Boronggoop from Dr Alexander Thomson, who, in 1836, had been the first European settler to arrive in the Geelong area.[5] Associated with the Port Phillip Association’s speculative venture onto the mainland from Van Dieman’s Land, Thomson had claimed large acreages in the Corio area, which had been converted into annual depasturing licences in 1840. Drysdale had initially employed a couple, Thomas and Jessie Clark, whom she had met on the voyage out, to build her hut and manage Boronggoop. Clark, unfortunately, had a drinking problem and was dismissed. In urgent need of a replacement, Read, whom Drysdale met through Alexander Thomson, offered her ‘a very respectable couple called Armstrong who had been 18 months in the colony from Scotland. They have six children … Wages 90 pounds, I to find food for all.’ They were employed as a family, ‘he to plough or shepherd, she to cook, wash, etc and their eldest son to shepherd’.[6]

Within two years, John Armstrong’s role had expanded from a labourer/shepherd into a supervisor covering all aspects of sheep management, overseeing the work of her shepherds, and protecting the flock from wild dog (dingo) attack and infection by scabies from neighbouring sheep straying onto their land in an era of unfenced grazing. He also made major improvements to Drysdale and Newcomb’s hut as well as constructing one for his own family.[7]

Drysdale seldom mentioned Vair Armstrong in her diary; however, the rare snippets illustrate the strengths required of working women on colonial properties. As the property’s cook, Vair catered for everyone, not just her own family and Drysdale and Newcomb, but also up to 14 visitors as well as seasonal shearers and other workers. She had two more children while at Boronggoop. During their first shearing season, Drysdale wrote:

We had all along been afraid that Vere [sic], Armstrong’s wife, would be confined before the shearing was over which would have been unfortunate as she is cook for the whole establishment, but she continued quite well & active the whole time until yesterday afternoon when she took ill.[8]

Vair later delivered her seventh child and was reported as ‘doing nicely’.[9] Sadly, the baby, Adam, died just over a month later from erysipelas, a bacterial infection of the skin that can be caused by birth complications. He was the only one of Armstrong’s 13 children not to reach adulthood.[10]

After this trauma, a young Irish immigrant, Biddy Trainer, was employed to assist Vair by doing the washing. A year later, Vair was again ‘ill’ and had another son, also called Adam.[11] The four oldest Armstrong boys also worked on Boronggoop. Children were employed as part of the family wage until aged 12 when they were entitled to a junior wage payment. The oldest boy, William, known as Willie, worked as a shepherd on Boronggoop and had previously shepherded for Read in Meredith. The Armstrong’s next eldest son, Robert Grieve, known as Bobby, worked as a cattle stockman from the age of 11.[12] The next two boys, Thomas and John (Little Jacky), also worked with sheep from a young age: when Thomas was six and Little Jacky was five they reportedly lost lambs under their watch, incurring their father’s wrath.[13]

While still an overseer at Boronggoop, John Armstrong developed his own business interests. Vair had brought her own cows with them and ran the dairy as well as the main household. In January 1842, John brought his own flock of sheep onto Boronggoop.[14] He also began breeding pure merino rams for Drysdale and, later, on his own account.[15] By mid-1844, he was clearly looking to acquire his own property and attended a number of sales to buy equipment. Initially, he considered a property at Buninyong near Ballarat. However, he eventually agreed to take over one of Dr Thomson’s licences.[16] In 1844, at Christmas, the Armstrong family moved to their own property on the western side of the Barwon River across from Boronggoop, known as Bush Station but sometimes called River Station, taking their stock.[17]

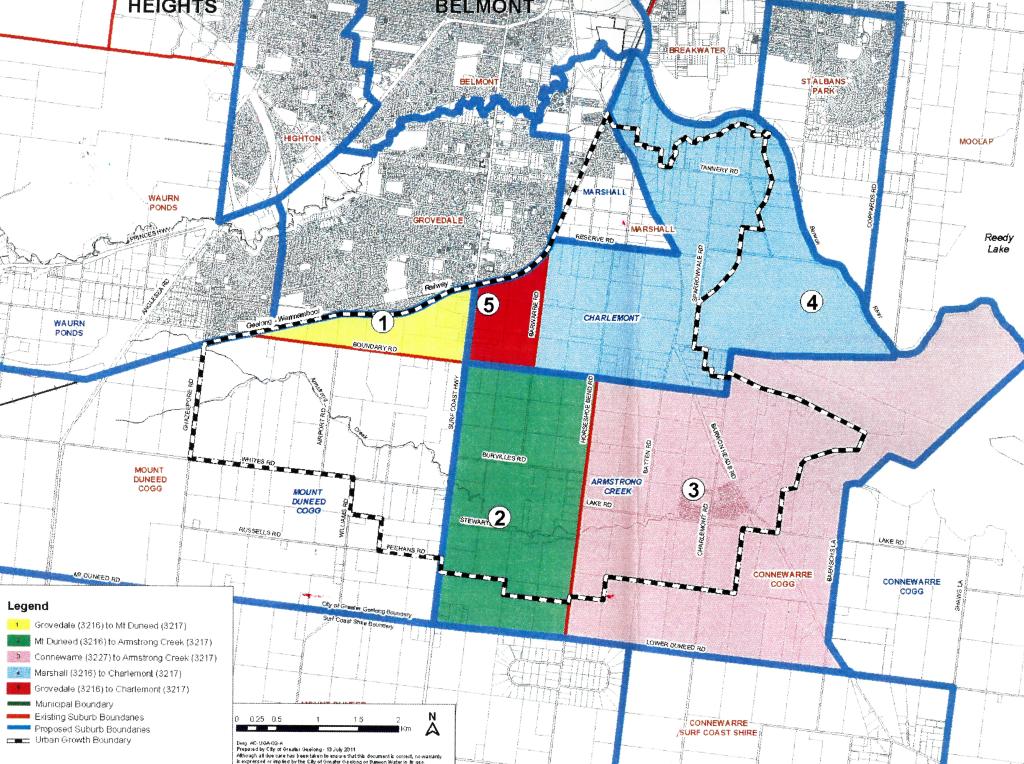

While the first five years of John Armstrong’s time in colonial Australia are relatively easy to trace, his time at Bush/River Station has proved more difficult to document. The original boundaries of Bush Station are poorly documented. However, some reports suggest that it encompassed an area spreading from the present site of the City of Geelong to Barwon Heads and Torquay.[18] Historical maps proved a useful resource in unravelling this history. Armstrong’s run is shown on maps for the parishes of Duneed and Conewarre, confirming that it did include the area shown as the urban growth area on planning maps. However, it probably extended beyond this. In 1846, part of Bush Station north of Mount Duneed along the ‘Waurn Chain of Ponds’ was resumed for suburban development around the growing town of Geelong. The resumed area is shown in Figure 2, which identifies suburban lots offered for sale from 27 April 1846 inscribed on an earlier 1842 map of the Parish of Duneed.

Figure 2: Area of Bush Station resumed and sold in 1846. PROV, VPRS 8168, SydneyD9; Duneed, Smythe.

Land originally in the name of Dr Thomson, lots 10–19 ranging in size from 188 acres to 640 acres, were offered for sale. This land was part of the Bush Station licence transferred to John Armstrong. As compensation, Armstrong gained grazing rights at Werribee Plains (1848–50), which became Black Forest Station (1850–52). The Geelong suburb of Grovedale, originally called German Town, was situated on lot 19.[19] Alexander Thomson was heavily involved in the German Immigration Committee, established to encourage German immigration in 1849. Charles John Dennys, who had purchased lot 19, subdivided this land into 1–10-acre plots for sale or lease to these immigrants. Thus, Grovedale was established on land that had been part of Bush Station.[20]

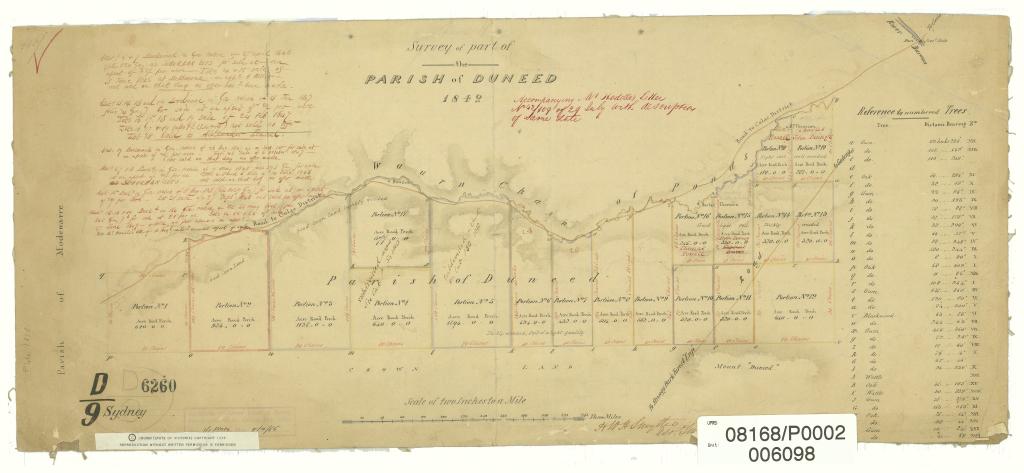

The southern extent of Bush Station can be gauged from Figure 3, which relates to a land sale in 1854. A rectangular area inscribed ‘Armstrong’s Sheep Station’ is shown in the bottom right corner of the map near the junction of Duneed Creek (now Freshwater Creek) and Thompson Creek. This would today be located near to where Ghazeepore Road crosses Freshwater Creek and north of Jan Juc, a town to the west of Torquay. Two sketch maps drawn in 1853 for the Parish of Bellarine show pastoral runs held by Elias Harding and Robert Zeally. These maps indicate that those people held the land along the south coast. Zeally’s run extended from what is now Breamlea to Torquay, and the sea in that area is known as Zeally Bay. Harding’s run extended down to Point Addis; however, as discussed below, it would have included land in the neighbouring Parish of Conewarre. These maps show that Armstrong’s land bordered them on the north-west.[21] This supports the proposition that his land went as far south as what is now the Freshwater Creek district but possibly not to the coast. However, whether he held land in what is now the Barwon Heads area is unclear.

Figure 3: Armstrong’s Sheep Station is shown in lower right section of this 1854 map on Duneed Creek. PROV, VPRS 8168/P2, Sale331; Duneed.

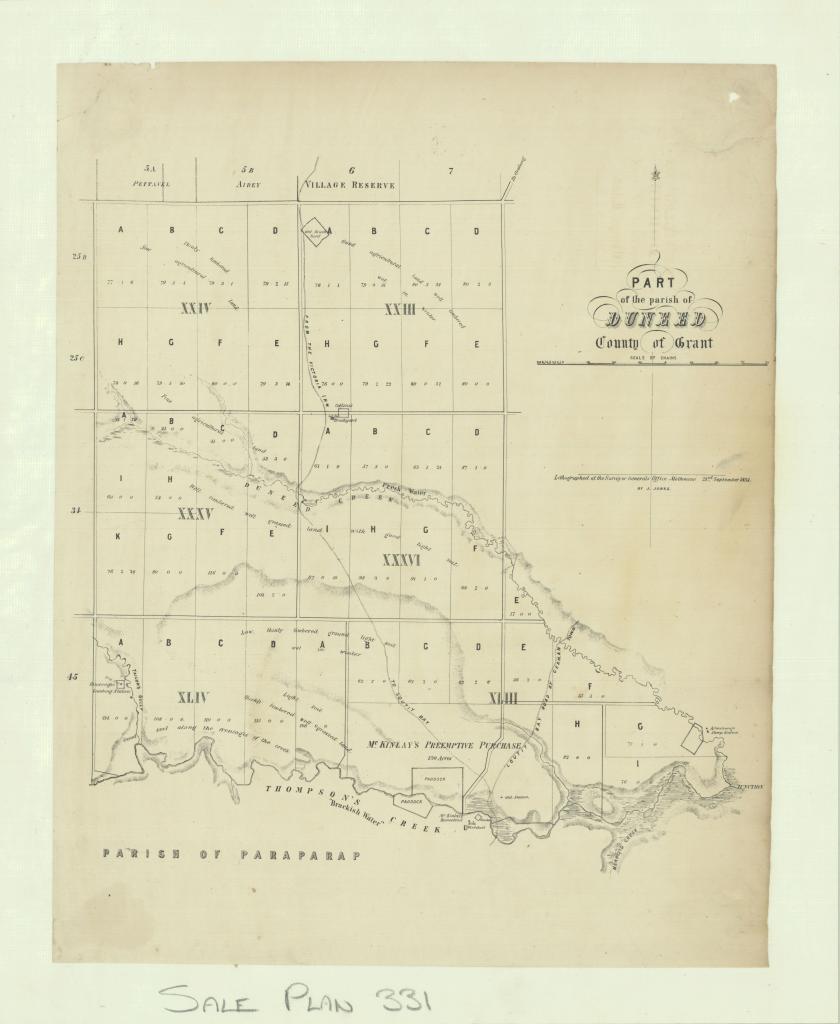

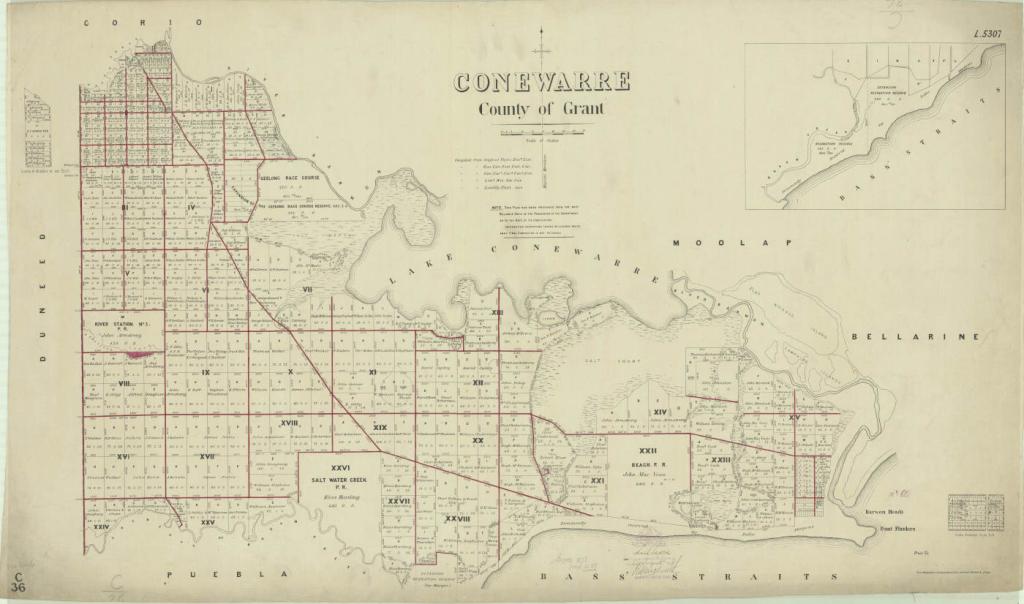

The eastern part of Bush Station lay within the Parish of Conewarre, which unfortunately is not well represented in the historic maps collection. Contemporary maps suggest that John Armstrong held the land west of the Barwon River in what is now the Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area. The remainder of Conewarre and the south coast were not included in the urban growth area. Again, the pastoral licences were resumed in 1853 and the land surveyed and offered for freehold sale. Squatters were given a pre-emptive right to purchase part of their runs prior to the land being offered for sale. Figure 4 shows that three pre-emptive purchases occurred, indicating that at least three pastoral leases covered this area: River Station No. 3 near Mount Duneed occupied by John Armstrong; Elias Harding’s Salt Creek Station, which had originally extended into the Torquay area as discussed above; and Beach Station occupied by John McVean who was Armstrong’s son-in-law, married to his eldest daughter Jemima.

John Armstrong selected as his pre-emptive block 320 acres just over the border from Duneed. Squatters generally selected the land around their homestead. Armstrong chose a site on Armstrong Creek rather than the area near the Freshwater Creek Station. He purchased two other blocks of 57 and 80 acres, respectively, to the south of his main holding. It is thus probable that sections VIII–XIII in Figure 4 were part of Armstrong’s run at Conewarre. However, Armstrong also purchased four blocks in section XIV of 80, 86, 91 and 71 acres, respectively, just to the north of John McVean’s pre-emptive selection, Beach Station. Despite being adjacent to a large salt marsh, these blocks were described as being ‘good agricultural land’.[22] Beach Station lay just to the west of where the town of Barwon Heads is now located. It is not known if McVean obtained the licence for his pastoral property from Dr Thomson or from his father-in-law, John Armstrong. However, those purchases suggest that Armstrong may have originally occupied this land and, hence, had prior knowledge of their quality, which supports the proposition that his land may have included the Barwon Heads area. Alternatively, he may have simply bought them on McVean’s recommendation, or on his behalf. Government land sales returns show John Armstrong purchasing four lots of 80 acres each in 1855. These were described as being located ‘near the Home Stations of Messrs Harding & Armstrong & Southward from the Race Course Reserve’.[23] This would place them in section IX or X (Figure 4). However, they are not recorded on this map.

Figure 4: This Parish of Conewarre map dating from 1878 shows the location of three pre-emptive land purchases after licences were resumed and the land surveyed and sold. PROV, VPRS 8168, PROCC36; Conewarre.

As land sales encroached, many squatters moved to larger properties in western Victoria that could still be held on depasturing licences. John Armstrong participated in this movement and held a licence for Allanvale of 80,000 acres near Great Western between 1854 and 1857. He also had a partnership with Silas Harding in Linlithgow Plains Station near Dunkeld of 44,256 acres in 1853, which later became Devon Plains.[24] As these properties were held on annual squatter licences rather than as freehold, it greatly reduced the capital requirements involved in accessing large holdings of land.

This investigation verifies the proposition that John Armstrong held under licence the land on which most of the Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Area is being established, therefore supporting the use of the name. However, there is strong, if not conclusive, evidence that Bush Station stretched west of the Barwon River from the Waurn Ponds Creek down to the coast just west of Barwon Heads. Its western boundaries took in Mount Duneed south to Freshwater Creek towards the town of Moriac but did not include the south coast areas around Torquay and Point Addis. This, together with his holdings near Werribee and in western Victoria, would have made him one of the largest landholders in the colony at that time.

Indigenous history

Analysis of John Armstrong’s pre-emptive selection block provides an introduction to the Indigenous history of the area. A pleasant walk within the Armstrong Creek developments along Stewarts Path (formerly Stewarts Road) leads into Dooliebeal Reserve. The urban growth area development lies on the traditional lands of the Wathawurrung balug (clan) of the Wadawurrung, part of the Kulin Nation.[25] Despite the edict of Lieutenant Governor La Trobe in 1842 that ‘grazing rights should not disturb the natural rights of occupation by the Aboriginal inhabitants’, European settlement quickly led to dispossession and depopulation.[26]

Armstrong Creek would have been a significant resource for Indigenous people and stone artefacts, middens and scarred trees were found in several areas around the River Station site.[27] The presence of Armstrong’s grazing operation would have contributed to this decline. While the nature of his relations with the original inhabitants of the land was not recorded, neither were any massacres.[28] Attempts to establish missions at Charlemont and Buntingdale near Birregurra were unsuccessful. By 1852, the remnant population were forced into the Geelong area seeking handouts of food.[29]

The one exception to this sad situation was the establishment of an ‘unofficial’ reserve at Dooliebeal near Mount Duneed on land that had been excised from the Crown land sales as a water reserve along Armstrong Creek, shown in red in Figure 4. John Stewart purchased allotments B and C of section VIII. These lands lay directly south of John Armstrong’s pre-emptive selection. Stewart offered part of his land adjoining the southern bank of Armstrong Creek as a safe place for the Wadawurrung to live. They resided there until 1861, able to continue their cultural traditions due to the philanthropy of Robert de Bruce Johnstone of the Comunn na Feinne Society in Geelong, which provided them with huts, clothing, blankets and medical care. Corroborees were held in conjunction with the society’s Highland Games.[30]

Dooliebeal Reserve remains a site of natural bushland today, accessible along the remnants of Stewarts Road.[31] In 1861, Duneed Reserve, comprising 1 acre for ‘Aboriginal purposes’, was officially established further along Armstrong Creek on the north side of Ghazeepore Road, part of section IX in Figure 4. By this time, only 11 Wadawurrung remained. The reserve was rescinded in 1907 due to non-use.[32]

Legacy

There is only limited information regarding John Armstrong’s activities while on Bush Station, possibly due to the remoteness of its location and the heavy demands of running such a large property. In the last years of his life, Armstrong began playing more of a community leadership role. In 1855, he became a member of the Geelong and Western Districts Agricultural and Horticultural Society.[33] In the same year, he was asked to be a trustee of the Greenvale Estate near Drysdale on the Bellarine Peninsula when its owner died suddenly in London. He organised the first Indented Heads ploughing competition on that property.[34] Unfortunately, this emerging public role was truncated by his early death.

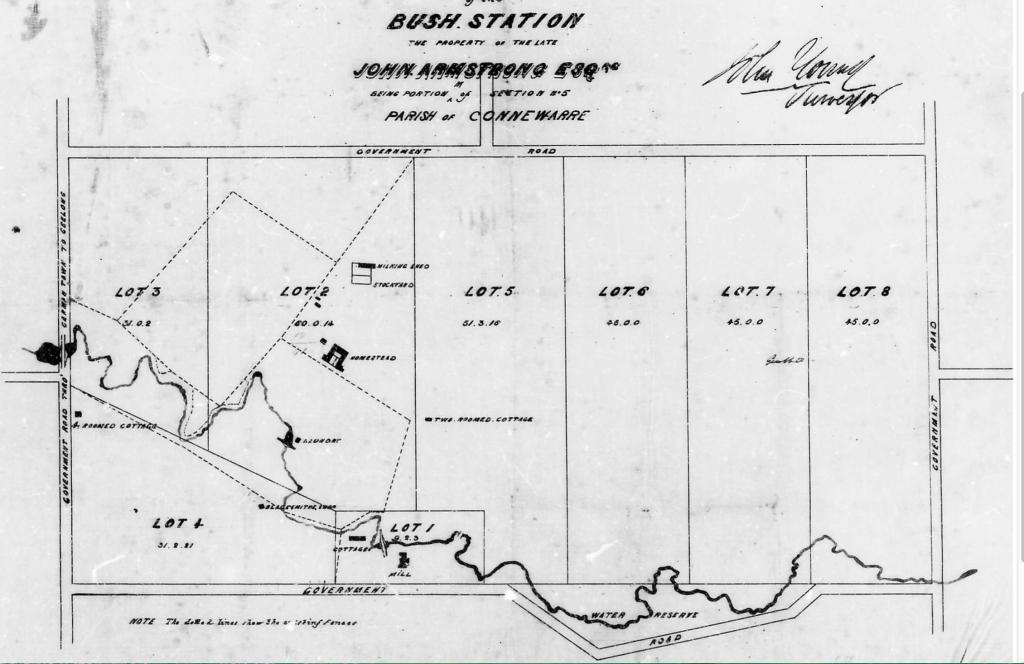

John Armstrong died suddenly on 17 October 1856 aged 46 after a small operation from complications associated with diabetes. The funeral was held at the Free Church of Scotland in Geelong. Four members of the new Victorian Parliament acted as pallbearers, a testimony to the esteem in which he was held. He had been elected as an elder of the Presbyterian Church while still working for Drysdale and Newcomb, and had been an active member of the congregation and patron of the church for many years.[35] Figure 5 shows that the River Station No. 3 freehold was subdivided and sold after his death. It gives a clear picture of where his homestead and other buildings were located, including the milking shed, stockyards, laundry and flour mill. Few physical remnants of that property remain.[36] A subsequent sale of livestock at Bush Station involved 17 pairs of bullocks, 30 dairy cows, two cart stallions, one of which was previously owned by Anne Drysdale, plus draught horses, brood mares, colts, fillies and foals.[37] Armstrong’s pre-emptive selection is today bounded by Burvilles Road, Horseshoe Bend Road, Stewarts Road (now Warralily Boulevard) and Torquay Road (Surf Coast Highway). It is being developed for residential blocks under the name Armstrong Grove.

Figure 5: Bush/River Station No. 3, subdivision and sale showing original location of buildings, Geelong Advertiser, 20 May 1857.

John Armstrong died intestate and his estate was granted to his wife Vair.[38] However, his children appear to have ultimately benefited, with most able to acquire freehold properties either individually or in joint ownership. His oldest son, William (1829–1895), having worked as a shepherd while still a child, began managing pastoral properties as a teenager, initially in conjunction with Dr Thomson, his father’s benefactor. In 1846, William took up Avon Plains and Molly Plains with Thomson. They took over Black Forest Run from John Armstrong in 1852. William later bought Hexham Park with freehold of 23,000 acres on which he bred Lincoln sheep. He also acquired Shadwell Park (4,000 acres) and Pirron Yalloak (5,400 acres) in the Mortlake area. William, who also owned several properties in New South Wales with his brothers, was a member of the Victorian Pastoralists Association and the Mortlake Shire Council (1864–71).

John Armstrong’s second son, Robert Grieve (1833–1886), who began work as a cattle stockman on Boronggoop, owned North Station and Salt Creek Station at Woorndoo in the Mortlake area. He was a member of the Mortlake Shire Council (1864–86), and an elder of the Woorndoo Presbyterian Church. The Armstrong’s third son, Thomas (1835–1886), settled in New South Wales and northern Victoria and bought East Charlton Station and Noorong Station (75,000 acres) at Moulamein near Deniliquin. He helped found the Australian Sheep Breeders Association. John Jnr (1837–1899) managed Gunbar Station near Hillston and Congoola on the Warrego in New South Wales, which he owned with three of his brothers, raising horses, sheep and cattle.[39] These four boys had worked on Boronggoop with their father and would have worked on Bush Station, learning sheep and livestock management skills that allowed them all to become successful graziers.[40]

The Armstrong’s fifth son, Peter Brown Palmyra, born at sea in 1839 and named for the captain and ship on which the family came to Australia, took up property in Queensland, dying there in 1882.[41] Adam, born in December 1842 on Boronggoop, managed family properties at Boort and South Shadwell in Victoria as well as properties in New South Wales and Queensland. He died in Melbourne in 1884.[42]

John and Vair Armstrong had five more children while they were at Bush Station. The boys, all of whom held properties, were Alexander (1845–1885), who died in Queensland; Huie Zeigler (1852–1919), who died in Orange, New South Wales; and James Forbes (1855–1895), who died in Charlton, Victoria.[43] In addition to their eldest daughter Jemima (1831–1885), who married John McVean of Beach Station, two other girls were born at Bush Station: Elizabeth Euphemia, born 1847, who married William Watson in 1872; and Vair, born around 1849, who married Joseph Cobham Watson in 1867 at East Charlton.[44]

Twelve of John and Vair Armstrong’s 13 children survived into adulthood and married. They all had large families, and it is possible that there could have been as many as 100 or more grandchildren. Vair Armstrong died on 13 June 1877 aged 68 in Garden Street, Geelong.[45] At the time of her death, her estate, consisting of her house and contents, 10 head of cattle with three calves and bank deposits, was worth 208 pounds.[46]

So, who was Armstrong?

Answering the question ‘who was Armstrong?’ uncovers the story of an early pioneering family that rose from humble beginnings as immigrant labourers, and who took advantage of the opportunities opening up as squatters occupied western Victoria to become established landowners in the new colony. While strong sheep husbandry skills and hard work were essential elements in this success, support from and cooperation with other pastoralists and community leaders were also a significant part of the story.

The names of many early European settlers of Victoria have been lost to modern society—or are enigmatically recorded in geographical features but with no record of their history in that area. This article demonstrates that it is possible to trace at least some aspects of their past lives even when official records prior to freehold land sales are limited. Their stories can be discovered in a variety of formal and informal sources. For John Armstrong, historic maps were particularly useful in plotting the boundaries of what was a large but only partially delineated pastoral lease. He is now commemorated in perpetuity by one of the largest urban developments in Victoria. It is important to keep his historical story alive for those who now live on his lands to prevent it being lost to modern society, as has occurred with many other early settlement stories.

Endnotes

[1] City of Greater Geelong, Armstrong Creek—whole of growth area, available at <https://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/armstrongcreek/armstrong/article/item/8cfafd49ea31e3f.aspx>, accessed 15 June 2024.

[2] City of Greater Geelong, Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Plan, background report, 21 April 2006, p. 7, available at <https://geelongaustralia.com.au/common/public/documents/amendments/8d4ddab421f2053-6.ACUGABackgroundReport.pdf>, accessed 14 January 2025.

[3] PROV, VPRS 17888/P1, LA/12/3218, Land Management – Place Names – Geographic Place Names – Naming Proposals – Armstrong Creek, Armstrong Creek Boundary Realignment – Frequently Asked Questions, 17 August 2011, p. 2.

[4] PROV, VPRS14/P0, Book No. 2, Assisted Immigrants 1839 – 1871, Palmyra 1839.

[5] PROV, VPRS19/P1, Inward Registered Correspondence, 40/503, ‘A. Drysdale requesting a letter of introduction to Captain Fyans and requesting permission to occupy a station of Dr. Thomsons’, 10 June 1840.

[6] Anne Drysdale, diary entry, 9 January 1841, in Bev Roberts, ed., Miss D & Miss N, an extraordinary partnership, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, p. 80.

[7] Anne Drysdale Diary, vol. II, online edition, diary entries, 15 – 24 November 1843, State Library ictoria (SLV).

[8] Drysdale, diary entry, 5 November 1841, in Roberts, Miss D & Miss N, pp. 105–106.

[9] Ibid., p. 106.

[10] Anne Drysdale Diary, vol. II, online edition, diary entries, 2 December 1841, 8 December 1841, SLV.

[11] Drysdale, diary entry, 31 December 1842, in Roberts, Miss D & Miss N, pp. 153–154.

[12] Ibid., 16 January 1841, 28 February 1842, pp. 80, 121.

[13] Ibid., 27 January 1842, 24 June 1842, pp. 117, 132.

[14] Ibid., 10 January 1842, p. 114.

[15] Anne Drysdale Diary, vol. II, online edition, diary entries, 27 November 1841, SLV.

[16] Ibid., 20 November 1844.

[17] Ibid., 23 December 1844.

[18] Anon., ‘The Armstrong family: 100 years in Australia’, Pastoral Times, 23 June 1939, p. 3.

[19] PROV, VPRS 8168/P1 Historic Plan Collection, MD28A: Duneed, Barrabool, Conewarre, Puebla, Selway, 1863 viewed in mapwarper.

[20] David Rowe, About Corayo: a thematic history of Greater Geelong, Geelong, City of Greater Geelong, 2021, p. 107.

[21] PROV, VPRS 8168/P1 Historic Plan Collection, Run Plan 412: Elias Harding Run 4.4.1853; Run Plan 410: Zeally’s Run 1853.

[22] PROV, VPRS 8168/P1 Historic Plan Collection, Sale 20: Byerley, 1855.

[23] Government Land Sales, Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 1 September 1855, p. 2.

[24] Anon., ‘The Armstrong family’.

[25] Rowe, About Corayo, Figure 2.01, p. 66.

[26] Ibid., p. 87.

[27] City of Greater Geelong, ‘3.5 Indigenous cultural heritage’, in Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Plan, background report, pp. 48–49.

[28] University of Newcastle, Colonial Frontier Massacres, Australia, 1780 to 1930, vol. 3, available at <https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/map.php>, accessed 28 October 2024.

[29] Rowe, About Corayo, pp. 87–88.

[30] Ibid., pp. 88–89.

[31] City of Greater Geelong, Dooliebeal Reserve, <https://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/parks/item/dooliebeal.aspx>, accessed 19 April 2025.

[32] Rowe, About Corayo., pp. 91–92.

[33] Anon., ‘Geelong and Western Districts Agricultural and Horticultural Society’, Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 5 March 1855, p. 2.

[34] Anon., ‘Indented Heads, a ploughing match’, Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 10 July 1855, p. 2.

[35] Anon., ‘Geelong’, Argus, 25 October, 1856, p. 5.

[36] City of Greater Geelong, ‘3.6 European Cultural Heritage’, Armstrong Creek Urban Growth Plan, background report, pp. 52–53.

[37] Gwen Threfell, Bush station, Blog, <https://mdpa.weebly.com/blog/bush-station>, accessed 9 January 2021; O’Farrell & Son, ‘Geelong live stock market’, Star (Ballarat), 5 May 1857, p. 2.

[38] PROV, VPRS28/P0 Probate and Administrative Files, 2/102, Grant of Administration, John Armstrong, 13 November 1856.

[39] ‘Armstrong, John (1837–1899)’, Obituaries Australia, <http://oa.anu.edu/obituary/armstrong-john>, accessed 9 January 2021.

[40] J Ann Hone, ‘Armstrong, John (1837-1899)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 3, 1969, online edition 2006, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/armstrong-john-23>, accessed 12 November 2022.

[41] Peter Brown Palmyra Armstrong, Victorian Births 1840, Queensland Deaths 1829–1964, accessed via Find My Past (subscription service).

[42] Anon., ‘The Armstrong family’.

[43] Alexander Armstrong, Victorian Births 1845, Victorian Marriages 1871, Queensland Deaths 1829–1964; Huie Ziegler Armstrong, Victorian Births 1852, New South Wales Deaths 1788–1945; James Forbes Armstrong, Victorian Births 1855, Victorian Deaths 1836–1985, accessed via Find My Past.

[44] Elizabeth Euphemia Armstrong, Victorian Births 1847, Victorian Marriages 1872, accessed via Find My Past; [Vair Armstrong, marriages], Argus, 30 December 1867, p.4.

[45] Vair Armstrong, Victorian Deaths 1836–1985, accessed via Find My Past.

[46] PROV, VPRS28/P0 Probate and Administrative Files, 17/192, Vair Armstrong, 7 February 1878.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples