Last updated:

‘The one who got away: Kate Rounsefell’s story’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 22, 2025. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Tara Oldfield.

While reading the 1892 Capital Case of Frederick Bailey Deeming held at Public Record Office Victoria, I was struck by the testimony of Kate Rounsefell. A single woman at the time, with a myriad of bad dating experiences behind me, I sympathised with Kate, a young woman who, for a fleeting moment, thought she had found a life partner—only to discover that her fiancé was a murderer, seemingly plotting to make her not just his next wife, but also his next victim. She was the subject of judgement and ridicule, particularly by newspapers of the time. I felt so deeply for her and wanted to know more. Most importantly, what happened to her after the case was closed? Not much has been written from Kate’s perspective. In fact, in a recent retelling, she was forgotten altogether! So, I dove into public records, newspapers and other sources to piece together a fuller picture of ‘the one who got away’.

Warning: this story contains records related to crime and murder and may be upsetting for some readers.

Introduction

It was a time before anyone knew of ‘red flags’ or ‘catfishing’ and 100 years before the term ‘serial killer’ entered the public vernacular. In 1888, Kate Rounsefell was a teenager travelling to Australia, ready to begin her adult life in the ‘promised land’. Within a few short years, she would be one of the most famous names and faces in the country, the subject of headlines, detailed pictorials and gossip. But that is just one chapter in her story. Who was Kate Rounsefell? How did she come to almost marry a killer? And what became of her?

A single perspective

I dive into this article from my perspective as a woman who was single into my late thirties. ‘I am a single woman’[1] is how Kate identifies herself throughout this story—an identity that, to this day, comes with considerable pressure and judgement. Texts by single women about the joys and disadvantages of singledom line my bookshelf. In The Unexpectant Joy of Being Single, Catherine Gray writes: ‘The wide-spread resistance to being single, the sad-sack stigma attached to it, means that people settle for and stay in relationships that they don’t truly want.’[2] If this is what women feel now, imagine being single in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

But Kate was not just a single woman; she was also once engaged to marry a murderer and was almost a victim herself. This article seeks to put her life, her story, to the forefront and take the focus off the killer she knew. While, in years past, serial killers have been glorified and the names of their victims barely remembered, a shift has occurred and now the spotlight is put on the innocent. The No Notoriety campaign asks media to elevate the names and likenesses of victims and limit the use of killers’ names in reporting.[3] In Bright Young Women (2023), Jessica Knoll does this through historical fiction, telling the stories of the women victimised by Ted Bundy without mentioning his name.[4]

For a very brief period of her life, Kate Rounsefell’s name was widely reported. Yet the way she was written about often took either a judgemental or sexist tone, with journalists ravenously reporting all the details of her recent romantic relationship. I grew up in the time of Britney Spears’s rise to fame. In her memoir, Spears writes:

I didn’t want to share anything private with the world. I didn’t owe the media details of my breakup. I shouldn’t have been forced to speak on national TV, forced to cry in front of this stranger, a woman who was relentlessly going after me with harsh question after harsh question. Instead I felt like I had been exploited, set up in front of the whole world.[5]

My aim with this article is to shine a light on the sides of Kate that no reporter sought to share: the trauma of being a celebrity and a victim; the joys and disadvantages of her singledom; and the family-oriented, well-travelled and successful life of Kate Rounsefell.

A bright, lively, strong-minded English girl

Kate Rounsefell grew up in the parish of picturesque Callington in Cornwall, England, where she lived with her parents Jane and Joseph, and siblings Mary, Lizzie, William and Thomas. Kate was just 13 when her mother passed away in 1886, followed two years later by her father. Their deaths must have rocked the tight-knit family and community where Joseph had lived his whole life. Eldest sibling Mary was married with children and William was in the process of completing an apprenticeship. With few options, Lizzie and Kate left the family nest to seek opportunities elsewhere, with Thomas not far behind.[6]

Callington, famous for inspiring the tale of King Arthur’s ‘Celliwig’,[7] was a mining town with a population of 2,000 in 1861.[8] Australia was seen as a land of great employment opportunity and an attractive proposition for single women from England, where women far outnumbered men and the marriage rate was falling.[9] In 1888, Lizzie and Kate, aged 25 and 15 years, respectively, set sail for Australia, arriving in Brisbane during a hot and wet year that saw more than 4,500 British immigrants pass through the Queensland port.[10]

Kate worked at a stationer’s shop[11] and enrolled as a church member, the congregation regarding her as a ‘bright, lively, strong-minded English-girl, well able to take care of herself’.[12] This was a wonderful appraisal for a teenager, far from home, perhaps still mourning her parents and trying to find her place in the world. It was speculated that she was romantically pursued by a ‘decent man’, though they were not formally engaged.[13]

‘Brisbane is new, bawny, uneven and half-finished’, commented the Canadian journalist Gilbert Parker in 1892. ‘It stands up with muscles working vigorously, and conscious of great latent power. It scorns to seek the shade, but bares itself defiantly to the sun.’[14] Kate felt uninspired by the ‘bawny’ city, her ‘decent’ suitor and stationer’s job. It is likely she missed her sister who had moved to Bathurst, and her brother who, by 1889, had migrated to Broken Hill.[15] So, in 1891, she left Brisbane, first visiting her sister, who was working as a milliner, and then her brother, who she helped with housekeeping while he worked in a store.[16]

By 7 January 1892, the sweltering heat of Broken Hill was taking its toll.[17] Kate was due another visit to her sister in the cooler climate of Bathurst, though she did not want to stay there. While Lizzie found Bathurst ‘pretty’, Kate found it ‘awfully dull’.[18] She was unsure where she wanted to end up. She must have felt some pressure from her siblings who were surely anxious for their sister to find a place to settle, as they had, and perhaps a husband to care for her. Kate would later recall that:

On January 7, I left Broken Hill to go to my sister at Bathurst. I went by train from Broken Hill to Adelaide, and from there to Sydney by boat, and to Bathurst by train. I sailed from Adelaide by the steamer Adelaide, which called at Melbourne.[19]

And so, the most famous chapter of Kate’s life began (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Photograph of Kate Rounsefell, Town and Country Journal, 2 April 1892, p. 33.

‘I don’t know much about you, and cannot say I like even what I do know’

Kate recalled: ‘I met Williams, as you know him, or Baron Swanson, as I know him, for the first time on board the SS Adelaide.’[20] The SS Adelaide was 112 feet in length with a crew of 10.[21] It boasted finishings in carved oak, satin wood and Hungarian ash, handpainted floral murals and a mosaic coat of arms as part of its interior. It had a music room, a smoking room and dining saloons, with domed skylights and electric lighting throughout (Figure 2).[22]

Figure 2: Alfred Martin Edsworth, Saloons of the SS Adelaide, State Library Victoria, <https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9917769953607636>.

During the Melbourne to Sydney leg of Kate’s journey, a mysterious, moustached man approached Kate in the saloon.[23] Standing five feet, five and a half inches, with brown hair and blue eyes, he was older than Kate.[24] An engineer by trade, he told her his name was Baron Swanson and he was recently arrived from England (Figures 3 and 4).[25]

Figure 3: The moustached man, Baron Swanson. PROV, VPRS 515/P0, Prisoner Record no. 25376.

Ten days prior, Swanson had written to Holt’s Matrimonial Agency looking for a suitable wife.[26] Now here was beautiful Kate, exactly the type of woman he had been seeking. His opening line did not make much of an impression. He asked if she was seasick. ‘No’, she scoffed.[27] The trip had been rocky to start, but she had received a compliment from one of the stewardesses on being such a good sailor.[28] Swanson pressed on, asking: ‘Can I fetch you anything?’[29] She told him she needed nothing.

The following evening when Swanson found Kate in the saloon again she had to admit she was indeed seasick. He invited her to a game of whist[30]—an English trick-taking card game. When she agreed, perhaps hoping it would take her mind off the nausea, he found two other players to make four.[31] Later, she said of their meeting that he was ‘very attentive and an acquaintance was formed’.[32] An acquaintance—not exactly a love match.

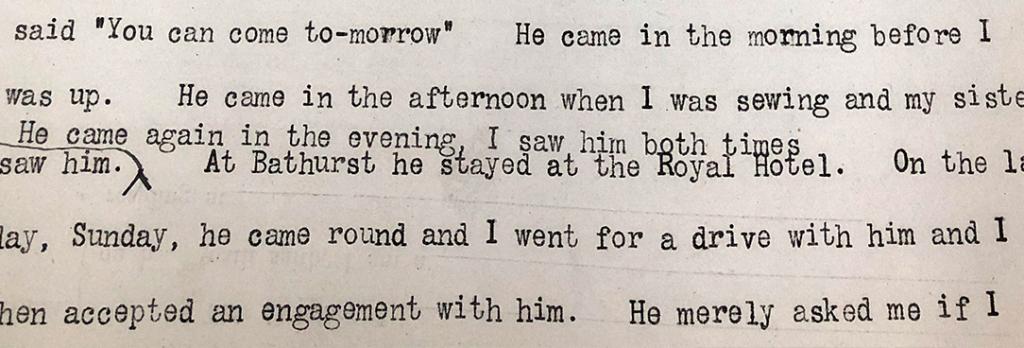

Figure 4: An excerpt from Kate’s statement. PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Case no. 261.

For Swanson, it was clear that persistence would be needed to capture independent Kate’s heart. Of the next day, Kate said:

We reached Sydney, and on the way up the harbour he lent me a powerful pair of marine glasses, which enabled me to see the full beauty of the harbour scenery. As we were nearing the pier I went up to him and said, ‘Well, Mr Swanson, I shall say good-bye to you now, and thank you for your kindness to me on board’. He said ‘Oh, don’t say good-bye yet Miss Rounsefell. Let me help you with luggage to your hotel or to the train.’[33]

Kate told Swanson that she was on her way to Bathurst. Well, as luck would have it, he was heading that way too. He told her of his plans to gain employment as an engineer and then proposed marriage.[34]

Kate recalled: ‘I thought he was joking and said “No! I couldn’t think of it. I don’t know much about you, and cannot say I like even what I do know.”’[35] It appears that Kate was not a woman to hold back her true feelings. She probably thought her rejection would lead to a quick departure on his part. It did not. As promised, Swanson helped Kate with her luggage, accompanying her to a meal at the Central Coffee Palace, then onto the Wentworth Hotel. Kate decided to spend the night in Sydney and continue to Bathurst the next day.[36] When checking in, Swanson asked if he might stay at the same hotel after taking her to Coogee for the afternoon.[37] Coogee, of beautiful sand and beach boxes, was hard for Kate to resist. They spent the rest of the day there, visiting the aquarium, sending a telegram to Kate’s sister letting her know of her impending arrival, and running into an old acquaintance of Swanson’s.[38]

While exploring Coogee, Swanson again proposed marriage—and again Kate refused. Regardless, he insisted that she accept a diamond and sapphire ring and wear an opal brooch that he happened to have on his person (Figure 5), since her pin was broken.[39] She stated: ‘He proposed to marry me, and I said “No” that I had no intention of marriage. Then he asked me to take the ring as a souvenir of his acquaintance.’[40] He told her: ‘I have had my loves before, but they were nothing in intensity to the passion I have for you.’[41]

Figure 5: Sketches in the Pictorial Australian, 1 March 1892.

Kate asked Swanson how it was that he had so many ladies’ jewels in his possession. He told her about a deceitful woman he had been unwittingly wooing, believing her to be single. He said he had bought the jewels for her but had not yet gifted them when he learned she already had a husband. He also had in his possession an abundance of women’s clothes. These were his dead sisters, he told Kate, before offering her some feathers. Kate did not care for feathers.[42] ‘I told him I could not wear the clothes of a dead woman even if I could overcome my objection—which I did not think possible—to taking gifts of clothing from any man not my husband.’[43]

Swanson was determined to make himself Kate’s husband. The next day on the train to Bathurst Kate agreed to ask her sister’s opinion about marrying him.[44] She would later tell the court:

Whilst in the train I looked at a copy of the [Sydney Morning Herald], and seeing my name in the shipping news I remarked to him ‘for once they have spelt my name correctly but, bye the bye, I don’t see yours.’ He said ‘Oh that is very probable, I booked on board.’[45]

Kate saw no reason to doubt him. Swanson offered her brandy from a silver flask marked F.B.D. She did not notice the inscription, refusing the drink without taking a sip. She informed him of her dislike of spirits. But she did like poetry, and he was pleased to spend the rest of the train ride reading to her.[46]

Arriving at Bathurst, Kate introduced Swanson to Lizzie who had come to greet her. Again, Swanson insisted on helping Kate with her luggage, hoping for an invitation home with the women. Lizzie, though, had already made plans. Kate told him he may visit the next day.[47]

Eager as ever, Swanson arrived the next morning so early that Kate was not yet up. Turned away, he returned in the afternoon. Kate was sewing while Lizzie and Swanson got acquainted. It appeared he made quite an impression, as Lizzie was soon urging Kate to accept Swanson’s offer of marriage. A few more visits ensued and, finally, on a Sunday afternoon drive around Bathurst, Swanson proposed again. This time, Kate accepted. Overjoyed, Swanson showered Kate with engagement gifts including perfume and two diamond rings (Figure 6).[48]

Figure 6: Kate Rounsefell’s deposition to the coroner, recounting her engagement to Swanson. PROV, VPRS 30/P0, Case no. 261.

One can understand the pressure Kate must have felt to marry. In today’s world, singles suffer through well-meaning friends pushing them to ‘stop being so picky’ and ‘settle down’. Kate was living in a time when major newspapers, including the Argus and the Bulletin, were extremely critical of ‘spinsters’ and marriage was viewed as the only respectable life for a woman.[49] Here was a persistent, attractive, apparently successful engineer from Kate’s home country, a man with ambition, a zest for travel and a love of poetry. He was not put off by her apparent dislike of liquor, the east coast or feathers! Instead, he spoiled her with stunning tokens of his affection. Most importantly, her sister approved. Lizzie later stated:

I do not think my sister loved him … she was willing to marry him, as what girl would not be! He was a man in every sense of the word; a manly man and a perfect gentleman and he offered her a good position.[50]

Lizzie probably thought or hoped that Kate could grow to love him. Perhaps Kate believed that too.

Swanson’s proposal was followed by excited discussion about the couple’s future. Kate expressed her dislike for New South Wales and suggested moving to Western Australia instead. ‘He said that was a good idea.’[51] Soon after, Swanson left for Perth, leaving Kate in Bathurst while he secured a job and prepared a home. A flurry of letters and telegrams passed between the betrothed couple and Kate’s siblings.[52] In a letter to Kate’s brother, Swanson wrote of his newfound position as an engineer of Frasers Goldmines, noting his salary and desire to move Kate to Western Australia as soon as possible (Figure 7).[53]

Figure 7: Letters from Baron Swanson to Thomas Rounsefell, February and March 1892. PROV, VPRS 937/P0, The Deeming Case (1892–1893).

In another letter to Thomas, Swanson wrote:

I love her more than I can tell you. And as you say with kindness and attention she will become herself again, I have built a nice little house here and made it comfortable as possible and I have everything arranged for our wedding the day after Dear Katies arrival.[54]

The mention of Kate becoming herself again makes me wonder if perhaps she had confided some discontent with life in Australia. Perhaps she hoped this move, and marriage, would finally make her happy. Her letters to ‘My Dear Baron’ certainly showed excited anticipation:

What is the town like? How large? … Do you like the place? What sort of place is it, and what dresses ought I get? … I do wish dear Baron, you would send a kind letter to [Lizzie], begging her to come, because we are never happy parted. If you did send for us both I would love you so for your kindness, when I am your little wife … How do you spend your time? How many hours do you work? Is it dirty work? Write all the news, because I want to know everything.[55]

In reply, Kate received ‘a letter full of loving messages and assurances of a happy future’. Swanson also sent her ‘a silver-mounted riding whip with the remark “I remember you said you would probably have some riding exercise”’.

In Bathurst Kate kept herself busy attending church socials with her sister and singing in the choir.[56] She could not afford the trip to Western Australia, so Swanson sent £20 for traveling expenses.[57] Though Kate was disappointed that her siblings could not accompany her, she pushed that sadness aside, packed her trousseau and, on 10 March, set out for Perth.[58]

A nameless terror

On the train, Kate heard passengers discussing a murder in Melbourne—right where she was headed. She ignored the gossip at first. A grisly murder was not something she need concern herself with. But the trip was long, and she eventually gave in, asking a fellow passenger for his copy of the Australasian.[59]

The 5 March edition included an article titled ‘A Ghastly Discovery’ (Figure 8). A woman inspecting a vacant home at 57 Andrew Street, Windsor, hoping to rent it, was put off by a horrid smell. The owner, Mr Stamford, did not seem too concerned at the time, but his agent, Mr Connop, found the smell so vile as to warrant police investigation. He called detectives who:

opened up the fireplace, and there in the space of 2ft by 18in, found the nude body of a woman of middle age huddled together in a shocking manner and built in under the hearthstone and masonry. It was apparent that murder had been committed, the skull being smashed in, and it was also apparent that the crime had remained thus hidden for over two months.

Figure 8: Part of the newspaper article Kate was likely reading on the train to Melbourne in 1892. 'A ghastly discovery’, Australasian (Melbourne), 5 March 1892, p. 24, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article138624226>.

The article took the reader back to Christmas 1891, when a prospective male tenant had enquired about moving in. After a bit of back and forth, the unnamed tenant decided not to stay:

Mr. Stamford says:—‘He was a bit curious … He told me he was an engineer’s tool-maker … He was a man of medium height, of fair complexion, with light moustache and beard … He seemed a mild-mannered person of gentlemanly demeanour, tolerably well dressed, and altogether of fairly pre-possessing appearance’.

Other witnesses described a woman they had seen in the company of this mystery man. The couple had been arguing after arriving together on a ship from Europe. Each witness knew the man by a different name, one of which was Williams.[60]

To Kate, and all those reading the news aboard the train, one thing was clear, a murderer was on the loose. Yet it also appeared that police were closing in on the killer. Kate made no connections at this stage. Upon arriving in Melbourne, she was joined by a friend who was to accompany her as she made passage aboard the ship for Perth. A fond greeting was followed by a stroll to the Federal Coffee Palace where a telegram from Lizzie was waiting. It read: ‘For God’s sake go no further.’ Kate had no idea why her sister, who had been cheering on her impending marriage, was now so against it. Kate asked her friend to send for an explanation and to accompany her outside. She recalled:

Naturally I was much distressed, and was unable to sit down or rest … Presently we noticed a crowd in front of a newspaper office, and enquiring the reason were informed that Williams, the murderer, had been arrested. I felt strangely moved, and I asked my companion to buy a paper. He did so, and read—‘Williams, alias Swanson, arrived at Southern Cross.’ I knew then the meaning of the telegram from my sister, and, overcome with a nameless terror, I fainted.[61]

The man she had just read about in the paper was the same moustached engineer she was engaged to. The clothes he had offered her, the jewellery, it was all from the woman he had murdered. His name was not Baron Swanson, it was Frederick Bailey Deeming, alias Williams.

Detectives Cawsey and Considine (Figure 10, left) arrived to question her. They were already aware of Deeming’s alias as Baron Swanson and that Kate was engaged to him:

At first they seemed to believe that I was in some way connected with the crime, but I had little difficulty in satisfying them of my utter ignorance of it. The jewellery, which was, I am now told, the jewellery of the poor dead woman, I handed over immediately and it makes me shudder now to think I have worn it, and as a love gift too!’[62]

Figure 9: One of the telegrams Victoria Police received alerting them to Kate Rounsefell’s whereabouts, 11 March 1892. PROV, VPRS 937/P0, The Deeming Case (1892–1893).

Upon further investigation it was found that, while building their house in Western Australia, Swanson had insisted on doing the fireplaces himself.[63] ‘Ominously one of the first things he ordered was a barrel of cement.’[64] It seems he was planning to make Kate his next victim, therefore ruling her out as an accomplice to murdering the woman, identified as Emily Mather, Swanson’s wife (Figure 10, right).

Figure 10: Left: Photograph of detectives Cawsey (left) and Considine (right) with Superintendent Kennedy (centre), 1900s, Victoria Police Museum, Victorian Collections. Right: photograph of Emily Mather, Victorian Collections.

‘She ought never to have been put in the box’

Needless to say, Kate never made it to Western Australia. A German couple, the Hirschfeldts, assisted the police in identifying Deeming. They had travelled to Melbourne a year prior on the Kaiser Wilhelm and had met Deeming and his wife Emily on board. They, perhaps at the suggestion of the detectives, took Kate in for the duration of the investigation, as she was required to stay in Melbourne and give evidence (Figure 11).[65]

Figure 11: Kate with the Hirschfeldts, Pictorial Australian, 1 April 1892

The inquest commenced quickly, in April 1892. One can only imagine how nervous young Kate must have been, walking into the packed court. Emily’s murder had become a sensation. Connections were being made to crimes overseas and Deeming was being investigated for killing multiple wives and children. Some would go on to speculate that he was Jack the Ripper. Journalists were only too happy to feed the public’s voracious appetite for news. As his bride-to-be and almost victim, Kate was a star player, appearing in newspapers across the country.

One article, in particular, highlights the extent of the public’s and the media’s obsession with Kate:

When the name of ‘Kate Rounsefell’ at the inquest on the Windsor tragedy rang through the Court, there was a stir of expectation among the men, a rustle of intense curiosity on the part of women. Williams bent over to his lawyer, and waited with evident eagerness the appearance of the young lady. There was a slight delay. Then a ladylike girl of 19, her neat figure clad in a close-fitting, dark blue dress, with cream-coloured front, bearing rows of large pearl buttons, and wearing a coquettish black hat over her elegantly-poised head, composedly advanced from an ante-room and entered the witness box.[66]

In a manner reminiscent of how female celebrities are described today,[67] the fixated journalist went on to describe Kate’s ‘pretty face’, ‘fresh peachbloom complexion’, ‘cherry ripe full lips’ and the ‘blushing of her face and neck’. ‘Demure’ glances were pointed out, as were her ‘quiet laugh’ and ‘shrug of the shoulders that would have done credit to a native of La Belle France’.

Kate nervously tapped her fingers on the ledge of the witness box. Deeming kept his eyes on her throughout her testimony, which must have been frightening. He was no longer the man she knew. He even looked different, having shaved off his moustache on the journey to Melbourne.

In what must have been a humiliating experience for Kate, all the couples’ love letters were read aloud:

She averted her face, blushing painfully. Williams listened with a grave face. He kept his eyes on the girl as she left the box, and followed her with his eyes till she disappeared into the ante-room. Then he muttered ‘She ought never to have been put in the box. It is a shame.’[68]

Not only did the hundreds at the inquest now know the intimate details of her private life and love letters, but soon so too did the entire country, with newspapers capturing every morsel, including Deeming’s criticism of her:

By the way, when Miss Rounsefell was in the box Williams adversely criticised one item of her costume. He remarked that her hat—a rather coquettish-looking article—did not suit her.[69]

Some reports did not look favourably on Kate, no doubt reflecting the tenor of conversations being had among the general public. The National Advocate called her ‘indiscreet, foolish, and perhaps more ambitious of marrying for money than for love’.[70] It was not the only newspaper to label Kate a gold digger. As Rachael Weaver pointed out: ‘The Bulletin’s indictment of Kate Rounsefell frames the revelation that her husband to be was a murderer (and very likely had been plotting her murder) as the just reward for her “gold digger’s” preparedness to marry for status and material comfort’.[71]

Kate must have felt she had no choice but to tell her side of the story. Prior to the inquest, she sat down with a journalist from the Argus: ‘I recognise that I had better confide it to some newspaper like yours which will publish it without exaggeration and misrepresentation’, she said, and went on to explain everything she had been through.[72] She must have felt nervous, worried that she had left something out or would be misrepresented. She insisted on adding a postscript, seemingly pointed at all those calling her a fool:

I have had a very fortunate, I should say a providential escape, and though it is easy to be wise after an event and to say ‘we knew it’ I really had an indefinable feeling that there was something wrong about my proposed marriage. It was not in the man’s manner—that was in every way unblameable, except, perhaps, on the score of being too kind—I cannot say what it was, but I ‘felt’ there was something wrong.[73]

The article, although reprinted around the country, did not quell the public or journalistic appetite for Kate-related news.

A capital case

The coroner found fit to send Deeming to trial for the murder of Emily Mathers. Kate testified on 25 April, again relaying her story in detail. There were multiple witnesses who had seen Deeming with his wife Emily prior to her death and who had heard his lies and deception in covering up his crimes and identity. There was also physical evidence—the rings and jewellery Kate had handed over—that was identified positively as belonging to Emily. With Kate’s help, Deeming was convicted of murdering his wife and sentenced to death (Figure 12).[74]

Kate was no doubt feeling lost and heartbroken. Her sister visited Deeming in gaol, perhaps trying to understand him somehow. She did not gain an understanding of him or his actions, but he did give her a map for gold he claimed was buried overseas. Spinning lies to the last, he began writing about his life while awaiting his death sentence. He initially wanted Kate to keep the manuscript but then reneged,[75] passing on his will and a note: ‘I give and bequeath to Kate Rounsefell, my will made on the ninth day of May 1892 in return of her kindness to me and as a token of the lies she told in court.’[76] His manuscript was destroyed.[77] It is unclear if Kate attended Deeming’s execution, though hundreds did. After his death, it was reported that Kate asked police for the jewels back,[78] though I find this unlikely.

Figure 12: Albert Williams alias Deeming, sentenced to death. VPRS 8369/P1, Reg No. 25376.

A curious assembly of crowds

After Deeming’s execution, Kate said goodbye not just to him, but to her dream of a home in Western Australia. She tried her best to return to some normalcy, travelling back and forth between her beloved brother and sister, between Broken Hill and Bathurst. But everywhere she went, she became a spectacle.

In May 1892, Kate’s travel by train to Adelaide caused ‘an unusual simmer of excitement’:

A crowd of people assembled around the carriage eager to catch a glimpse of the fair passenger … A local gentleman (married), who travelled up in the same carriage, describes Miss Rounsefell as a very prepossessing, chatty and ladylike girl. She received much attention at Ballarat and on leaving the station stated who she was, and informed our friend of the sensational incident of her life. She stated that she has been up at Broken Hill, where she proposes remaining some time. Our friend is of opinion that a far less villainous man might be excused from falling in love with the chatty young lady.[79]

I cannot help but think that poor Kate was unaware her friendly chat was to be broadcast to the country. On another trip:

The anxiety to get a view of Miss Rounsefell was so great that the officials had great difficulty in keeping order and preventing the crowd rushing the refreshment rooms. On Miss Rounsefell emerging from the latter and attempting to approach the compartment in which she was travelling, the excitement was intensified. The eager crowd crushed and jostled, and had it not been for the promptness of the guard in getting the passengers seated and signalling the driver to steam out at the first opportunity that presented itself, an accident of a serious nature must have occurred.[80]

It is not surprising that Kate soon left Australia for a fresh start. She had told Deeming that she and her sister were never happy apart.[81] Lizzie and Kate finally found a place in the world they both found ‘pretty’ enough to settle down.

Oh Canada!

Kate and Lizzie immigrated to Montreal, Canada, in 1898.[82] Kate’s experience of having worked in a stationary shop in Brisbane served her well, as she initially took on work at a dry goods store, before following in her sister’s footsteps and training as a milliner.[83] After 12 years working at Fairweather’s Ltd., Kate, aged 53, opened her own millinery business in 1926 (Figure 13). The Gazette gave the business a rave review in 1930:

At Kate Rounsefell, 1426 Peel Street, opposite the Mount Royal Hotel, is a truly wonderful variety of the most unexpected, artistic and becoming hats that could be imagined. So varied are they, and each so lovely, that it is an aesthetic treat just to try them on.[84]

One cannot help but remember back to Deeming’s comment at the inquest. Did he insult her hat because he knew it would hurt her? Because she, in fact, had a real talent for style?

Figure 13: Advertisement for Kate’s millinery, Gazette (Montreal, Canada), 9 September 1929, p. 30, <https://www.newspapers.com/image/421275091/>.

Lizzie married and had children, but Kate never did. She had told Deeming from the start that she had no intention of marrying, and her brief change of mind must have been one of her biggest regrets. Sadly, Lizzie died in 1904, aged 41, leaving Kate without her beloved sister. In the years that followed, Kate learnt French, travelled to Paris and built herself a successful career. She passed away in 1955 aged 82.[85]

Figure 14: Photograph of Kate, Town and Country Journal, 2 April 1892.

Conclusion

Kate Rounsefell’s life was unconventional in more ways than one. Nearly a wife and victim of Frederick Bailey Deeming, she was also a wandering spirit, a successful milliner, a business-owner and a single woman who lived life on her own terms. Still today, so many singles are judged and pitied, viewed as failures in a society obsessed with coupledom. Pressure to marry comes from all corners; singles are told to ‘settle down’ but not to ‘settle’ for anything less than love. Kate was not a failure or a gold digger. She sought happiness and a home and finally found it in Canada. She more than survived: she lived a full and fabulous (single) life.

Endnotes

[1] PROV, VA 2825 Attorney-General’s Department, VPRS 264 Capital case files, Albert Williams [alias Deeming].

[2] Catherine Gray, The unexpected joy of being single [audiobook], Aster, UK, 2018, preface.

[3] No Notoriety, No name. No photo. No notoriety, available at <https://nonotoriety.com/>, accessed 19 September 2024.

[4] Jessica Knoll, Bright young women, Macmillan, London, 2023.

[5] Britney Spears, The woman in me, Simon & Schuster, Sydney, 2023, pp. 104–105.

[6] Wikitree, Kate Rounsefell (1873–1955), available at <https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Rounsefell-108>, accessed 9 July 2024.

[7] Callington Town Council, History, available at <https://callington-tc.gov.uk/community/history/>, accessed 9 July 2024.

[8] Cornish Studies Resources, Callington, available at <https://bernarddeacon.com/cornish-towns/callington/>, accessed 9 July 2024.

[9] Margaret Sales, ‘Redundant women in the promised land: English middle class women’s migration to Australia 1861–1881’, thesis, University of Wollongong, 1983, pp. iv, 33–34.

[10] Helen Woolcock, ‘Immigrant health and reception facilities’, in Brisbane History Group and Rod Fisher (eds), Brisbane in 1888: the historical perspective, Brisbane History Group, Petrie Terrace, 1989, p. 79.

[11] PROV, VA 2825 Attorney-General’s Department, VPRS 264 Capital case files, Albert Williams [alias Deeming].

[12] ‘Miss Rounsefell’, South Australian Register (Adelaide), 1 April 1892, p. 5, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48227641>.

[13] ‘Alias?’ Bulletin (Sydney), 26 March 1892, p. 8, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-449992125>.

[14] Graeme Davison, ‘New, bawny, uneven and half-finished: Brisbane among the Australian capital cities’, in Brisbane History Group and Rod Fisher (eds), Brisbane in 1888: the historical perspective, Brisbane History Group, Petrie Terrace, 1989, p. 151.

[15] Wikitree, Thomas Rounsefell (1869-1939), available at <https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Rounsefell-109>, accessed 9 July 2024.

[16] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[17] ‘The murderer’s wooing’, Narracoorte Herald (SA), 18 March 1892, p. 3, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page17361464>.

[18] ‘Swanston’s love letters’, Glen Innes Examiner and General Advertiser (NSW), 29 March 1892, p. 3, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page23887345>.

[19] ‘The Melbourne inquest’, Telegraph (Brisbane), 13 April 1892, p. 5, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article173294877>.

[20] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[21] ‘The S.S. Adelaide’, Evening Journal (Adelaide), 3 July 1888, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page22411582>.

[22] ‘The S.S. Adelaide’, Argus (Melbourne), 8 January 1884, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11840780>.

[23] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[24] PROV, VA 1464 Penal and Gaols Branch, Chief Secretary’s Department, VPRS 515 Central Register for Male Prisoners, Albert Williams, no. 25376.

[25] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[26] Rachael Weaver, The criminal of the century, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Kew, 2006, p. 39.

[27] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[28] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[29] Ibid.

[30] ‘The Melbourne inquest’.

[31] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[32] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[33] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] PROV, VA 2825 Attorney-General’s Department, VPRS 264 Capital case files, Albert Williams [alias Deeming].

[37] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] ‘The Melbourne inquest’.

[41] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[42] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[43] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[44] Ibid.

[45] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Weaver, The criminal of the century, p. 138.

[50] Ibid., p. 137.

[51] ‘The Melbourne inquest’.

[52] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[53] PROV, VA 724 Victoria Police, VPRS 937 Inward registered correspondence, The Deeming Case (1892–1893).

[54] Ibid.

[55] ‘Swanston’s love letters’.

[56] Ibid.

[57] ‘The Melbourne inquest’.

[58] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[59] Ibid.

[60] ‘A ghastly discovery’, Australasian (Melbourne), 5 March 1892, p. 24, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article138624226>.

[61] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[62] Ibid.

[63] ‘The monster of Windsor’, Mail (Adelaide), 2 June 1951, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55785891>.

[64] ‘Irate public dubbed hanging too good for loathsome lady-killer’, Daily Mirror (Sydney), 17 June 1950, p. 7, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article274318793>.

[65] PROV, VA 2550 Office of Public Prosecutions, VPRS 30 Criminal trial briefs, Case no. 261.

[66] ‘The Windsor tragedy’, Daily Northern Argus (Rockhampton), 19 April 1892, p. 7, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213431958>.

[67] ‘Welcome to the summer of Margot Robbie’, Vanity Fair (USA), August 2016, <https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2016/07/margot-robbie-cover-story>.

[68] ‘The Windsor tragedy’.

[69] ‘Incidents at the inquest’, Advertiser (Adelaide), 9 April 1892, p. 5, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25325377>.

[70] ‘Miss Katie Rounsefell’, National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW), 4 May 1892, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156652428>.

[71] Weaver, The criminal of the century, p. 137.

[72] ‘The murderer’s wooing’.

[73] Ibid.

[74] PROV, VA 2825 Attorney-General’s Department, VPRS 264 Capital case files, Albert Williams [alias Deeming].

[75] Weaver, The criminal of the century, p. 63.

[76] PROV, VA 2620 Registrar of Probates, Supreme Court, VPRS 7591 Wills, 51/087 Frederick Bailey Deeming.

[77] Weaver, The criminal of the century, p. 274.

[78] ‘The Deeming case revived’, Argus (Melbourne), 20 June 1898, p. 5, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article9838922>.

[79] ‘Miss Kate Rounsefell’, Avoca Mail (Vic.), 31 May 1892, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202119968>.

[80] Ibid.

[81] ‘Swanston’s love letters’.

[82] Wikitree, Kate Rounsefell (1873–1955).

[83] Ibid.

[84] ‘Brims return and fabric trims hats’, Gazette (Montreal), 15 March 1930, p. 44, <https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/419327112/>.

[85] Wikitree, Kate Rounsefell (1873–1955).

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples