Last updated:

‘Reclaiming the slums: the Housing Commission of Victoria’s plans for inner Melbourne’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 20, 2022. ISSN 1832-2522 Copyright © Sebastian Gurciullo.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Housing Commission of Victoria (HCV) embarked on building large apartment towers for people on relatively modest means. This came at the culmination of more than 30 years pursuing an ambitious housing program to remove substandard housing across the city. While the apartment towers, such as those built in Flemington at Debney Meadows Estate, were a major change in Melbourne’s built form, the HCV was successful constructing these across many suburbs in the inner city in order to house thousands of people. It was when the HCV became involved in proposals for large-scale urban renewal, as was the case in the Carlton Comprehensive Redevelopment Area, that it met very stiff community opposition. This article explores these two examples, the Debney Meadows site and the Carlton redevelopment zone, through the abundant HCV archive, to show both the care and attention that the HCV brought to planning housing, but also its overreach in proposing to demolish half of a heritage suburb that was already undergoing spontaneous grassroots renewal.

Grand plans: a requiem

In the 1960s and 1970s, some of Victoria’s largest postwar government agencies had plans to transform Melbourne, particularly the inner suburbs. Unlike recent decades, in which urban development is often driven in an ad hoc way by private sector interests, these government agencies had the power to both plan and build large-scale infrastructure, and they had big, ambitious and visionary ideas. However, for many of the people they would have impacted, these plans often seemed like externally imposed solutions emanating from autocratic bureaucracies that seemed to show little regard for the local communities they were supposed to serve. Community consultation as we understand it today was not something these agencies undertook in the 1960s. And so, the stage was set for a clash between local inner-city communities and the government agencies that were determined to ‘renew’ their suburbs.

As Guy Rundle recently observed in connection to the profound challenges wrought upon the City of Melbourne by the COVID-19 pandemic over the past two and a half years, the battles of the 1960s offer a thought-provoking contrast to the present. Back then, as Rundle reflects, the progressive side of politics in Melbourne had a distinctly urban focus:

State Labor, and the Labor and progressive independents in the [Melbourne City] council, were energised by the inner-city residents’ associations which had risen in opposition to a wild freeways plan and mass demolition by the Housing Commission. They set the stage for a process of rethinking what a city centre should be.[1]

Rundle’s nostalgic observations, made from our neoliberal present in the midst of a major crisis, are directed at what he perceives as the lack of any coordinated or imaginative vision in urban policy that is adequate to present circumstances. He implies that, in the 1960s and 1970s, the oppositional campaigners had worthy government adversaries with grand, if questionable, plans. From the vantage point of the present—an era in which a neoliberal approach to urban planning and policy prevails—the relative autocracy of large government bureaucracies inspires a kind of nostalgia. Instead of being geared predominately to profiteering and instilling competitiveness, mid-twentieth-century urban planners sought to plan rationally and for the public good, if often with a heavy hand. In contrast, the current housing affordability crisis is met with piecemeal remedies and policies that largely fail to address the supply side of the equation, while large-scale redevelopment sites lack the probity of a comprehensive and coordinated approach based on sound planning, deliberation and a recognisable sense of the public good.[2]

It is difficult for us to comprehend the extent of the power of postwar government bodies over local communities in the 1960s and the active role they took in shaping the suburbs where those communities lived and worked. These days, a great deal of what was once done by government bodies like the Housing Commission of Victoria (HCV) or the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) has been devolved, and much of urban policy is now carried out, in a less centralised and regulated way, by the private sector and under-resourced local government bodies.[3] Few people today would remember the big coordinated plans the HCV developed and attempted to implement in the 1960s and 1970s. Those of us who did not live through this era will be unfamiliar with the organisational culture and values that such an agency embodied, and the struggle that was required to force it to change its plans to better fit impacted communities.

The culture of the HCV was imbued with a quasi-evangelical belief in the efficacy of modernism. In this respect it was not unusual. There was widespread enthusiasm in post–World War II Australia ‘for modern forms of architecture, transport and design’. From this perspective, Melbourne’s inner city, with its industrial-era mix of manufacturing often abutting terrace housing, was seen as the urban legacy of a waning era, ‘a “slum” region of deteriorating housing, poverty, red light areas, homelessness and crime’.[4] Therefore, urban redevelopment along modernist principles was seen within the HCV and other agencies as both an economic and social necessity for inner-city Melbourne. However, by the time its visionary plans were ready, the demographics of this urban landscape had dramatically changed, setting the scene for a clash between the new inner-city communities and big government agencies involved in urban planning and infrastructure.[5] In this changing social environment, it was only relatively small-scale projects, those that did not entail suburb-wide demolitions of so-called ‘slum areas’, that succeeded in being implemented. I will illustrate this by contrasting two sites in inner Melbourne—the Debney Meadows Estate in Flemington and the Carlton Comprehensive Redevelopment Area—to evoke some of the benefits and drawbacks of centralised government intervention in housing and urban planning.

Debney Meadows Estate

The Housing Commission flats of Debney Meadows Estate still accommodate thousands of people. In July 2020 they rose once more to public prominence as an early focal point for Melbourne’s second major community outbreak of COVID-19. Around 3,000 people across nine apartment towers (including those in the nearby North Melbourne estate) were ordered to stay home. I watched with dismay as this human drama unfolded right in front of my own home, which is located directly adjacent to the Debney Estate.

Figure 1: The Flemington high-rise flats and part of Debneys Park during the lockdown of the buildings, July 2020. Author’s personal collection.

Whether you love them or loathe them, these iconic inner-Melbourne towers loom large above the surrounding streetscapes and are replicated in suburbs across the inner city, from Prahran in the east to Williamstown in the west. The Housing Commission’s correspondence files document the development and building of these towers that have housed thousands of Melbourne families over the years, particularly immigrant communities and others on low incomes. The construction of high-rise towers was the culmination of an ambitious housing program that was initiated by the Victorian Government in 1938 in response to the identification of large swathes of substandard and slum housing in the inner suburbs at that time.

Though mainly composed of letters, the correspondence files also have hundreds of plans and drawings and other visual material related to the design, layout and internal fittings of each apartment tower and their surrounds.[6] The files about the Flemington flats go back to the late 1950s, when Debney Meadows Estate, as the site was officially called, was comprised of open space, WWII-era industrial buildings and a few run-down weatherboard houses.

The development of the site was not without controversy. Until 1957, what was known as Debney’s Paddock was mostly owned by the City of Melbourne and had been earmarked for public parkland. The council revoked this long-standing intention and instead decided to renew industrial leases for a further six years, leading to fierce community and political opposition. The dispute, which lasted for more than five years, was resolved by EF Borrie, MMBW chief planner, who invoked powers over metropolitan planning to determine that most of the 15-hectare site would eventually become parkland (which is today known as Debneys Park), except for 2 hectares that would be set aside for public housing (which is today the site occupied by the HCV flats).[7]

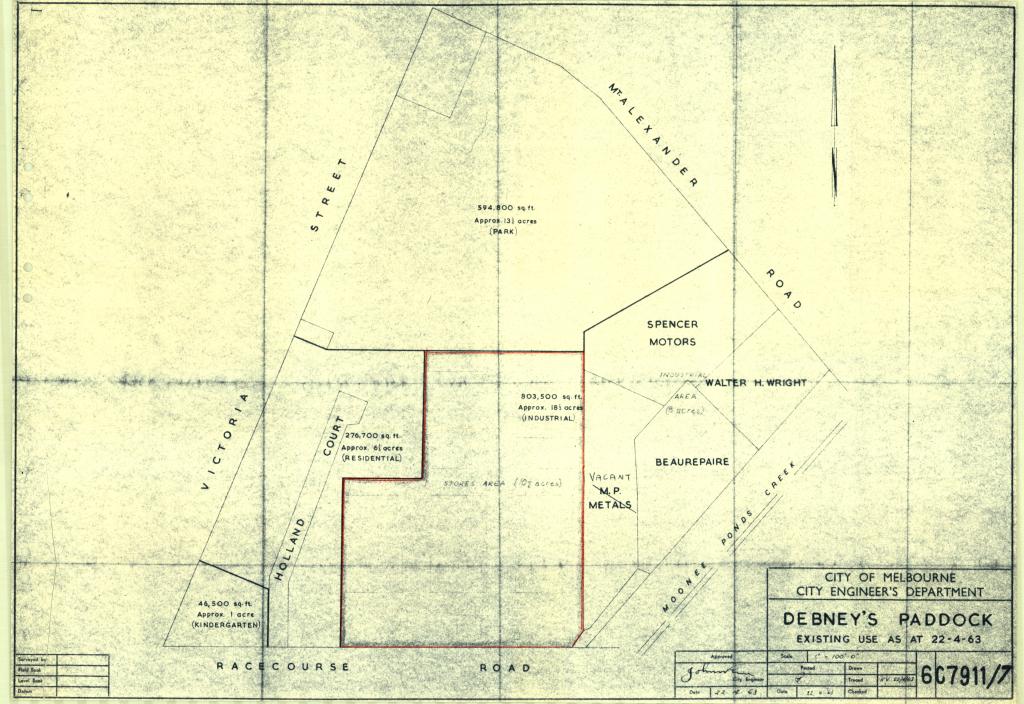

Figure 2: The site of the Housing Commission Victoria development in Debney’s Paddock showing the existing land uses at 22 April 1963. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 59, File D7 Debney Meadows Estate – Part 1, Drawing no. 6C7911/7.

Planning for the site commenced in the late 1950s. In 1958, Victorian Minister for Housing Horace Petty signalled to the secretary of the HCV that he supported the urgent construction of high-rise towers in inner-Melbourne HCV estates.[8] This meant that the HCV would develop the Flemington site as a ‘mixed estate’, a combination of medium walk-up buildings and high-rise towers. After resolution of the dispute about what proportion of the site would become parkland, no significant public opposition was raised in connection with the development of public housing.[9] This was the case even though the first of the HCV’s 20-storey high-rise towers was built there and was a major departure for the area in terms of both height and density. As has been observed by Peter Mills, the development did not directly threaten the housing stock of a gentrifying area, as occurred in the Carlton Comprehensive Redevelopment Area (which will be explored in the next section).[10] Unlike many of the other inner-suburban Housing Commission projects of the era, initially Debney Meadows Estate was a largely vacant site, with the exception of six timber homes in bad repair on the western side and some industrial use on the southern and eastern boundaries that had been erected hastily during WWII (see Figure 2). A large part of the construction site was on land donated by Melbourne City Council after the resolution of the dispute about the future of Debney’s Paddock.

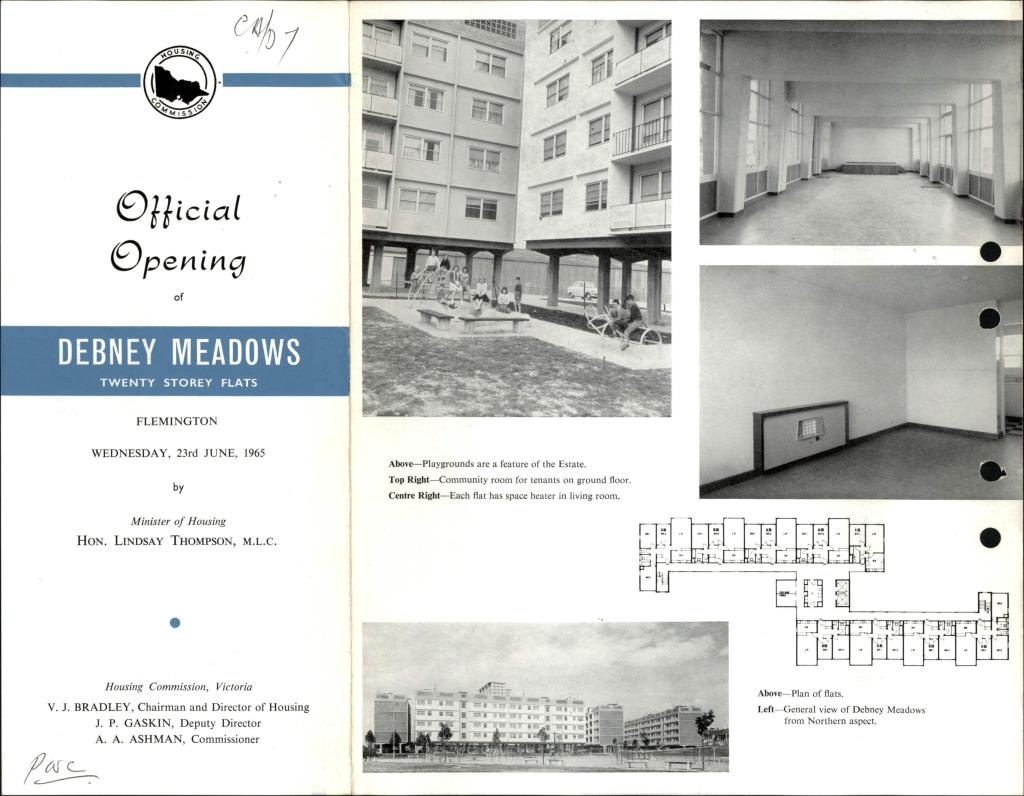

The first part of the housing project was the construction of the walk-up buildings (up to four storeys) along Victoria Street in Flemington. The first of four 20-storey towers, situated directly adjacent to Racecourse Road, was completed in 1965; three more almost identical towers were later added alongside (all within the red boundary in Figure 2, which shows the previous industrial land use on the site). This first tower comprised 180 flats (40 three-bedroom, 120 two-bedroom and 20 one-bedroom flats) and was intended to primarily house small- to medium-sized families. This first tower now features a recognisable ‘cloud’ sculpture on its roof, added in 1995 after renovations designed by ARM Architecture (referencing Oscar Niemeyer’s Church of St Francis of Assisi in Brazil).[11] The first tower served as a kind of template, which became known as a Z-block, being replicated elsewhere with slight variations at other HCV estates.

Figure 3: Looking east along Racecourse Road at the first of the Flemington high-rise flats completed in 1965, with the ‘cloud’ sculpture now on the roof, April 2021. Author’s personal collection.

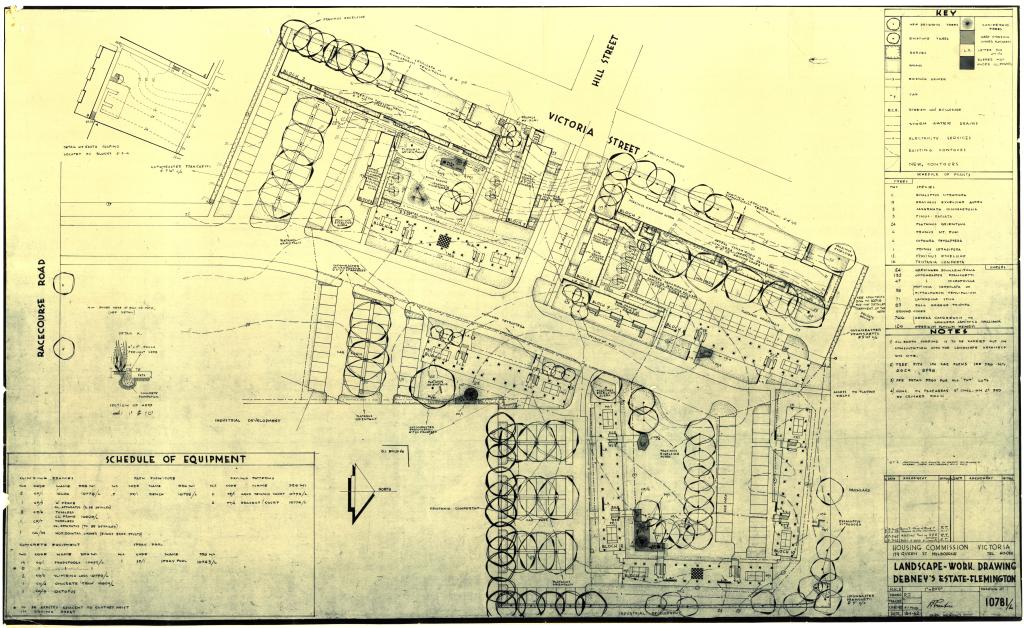

Each flat included a living room/dining area, kitchen, bathroom with private WC (toilet), entrance hall, telephone and TV outlets, as well as built-in cupboards for storage. Laundry facilities (washing and drying) and a central chute for rubbish disposal were located on each floor. The buildings had two lifts and a community room on the ground floor. Gas heaters were installed in the living room of each flat, while hot water heating was centralised and costed into rents. Car parking and children’s playgrounds were at ground level in the surrounds of the building. Access to the apartments was via a walkway ‘balcony’ that allowed for better lighting and cross-ventilation as windows could be located on two opposite sides of each apartment. Excluding the frame and structure, the flats were largely made of prefabricated parts of precast concrete that were sealed and bolted into place.[12]

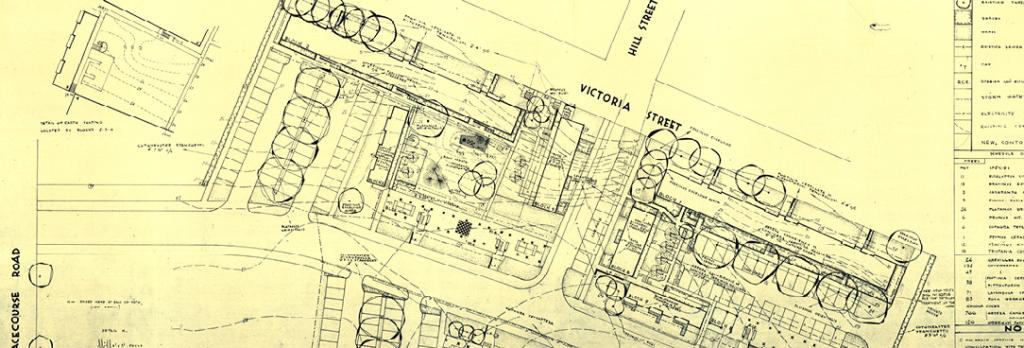

The HCV files contain a great deal of evidence of the careful planning, consultations and thought processes involved in building the flats, including the ways in which problems and issues were resolved. It is clear from this ample documentation that much thought was given to details such as floor layouts, tree plantings, the adjoining parkland (Debneys Park), playground equipment, and the provision of amenities and facilities for residents. Great attention was paid to landscaping, particularly tree plantings, which was overseen by the landscape architect Margaret Hendry, who, earlier in her career, had contributed to Canberra’s landscape design.

Figure 4: Details of the tree plantings and landscaping in the low-rise part of Debney’s Estate. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 60, File D7 Debney Meadows Estate – Part 3, Drawing no. 10781/L.

The official opening (by Minister for Housing and Forests LHS Thompson MLC) of the first of the 20-storey towers at Debney Meadows took place on 23 June 1965. The official party visited flats on the twentieth floor, some of which had been furnished for display purposes by Melbourne department chain store Waltons, no doubt in the hope that tenants would be enticed to replicate the fittings in their own flat.[13]

The official brochure boasted that the estate was ‘Australia’s largest and most modern complex of flats’ and emphasised the ongoing collaboration with the City of Melbourne that would see ‘extensive parkland improvements to the playing fields to the north of the estate’. These improvements would include ‘the construction of a modern pavilion with changing, toilet and shower facilities, upgrading the sports ground, the construction of a large children’s playground and an extensive tree planting programme’.[14] The brochure foreshadowed further collaborations between HCV and the City of Melbourne at other sites across the inner city.

Figure 5: One side of the official opening brochure for Debney Meadows’ first 20-storey flats in June 1965. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 59, File D7 Debney Meadows Estate – Part 1, official opening brochure.

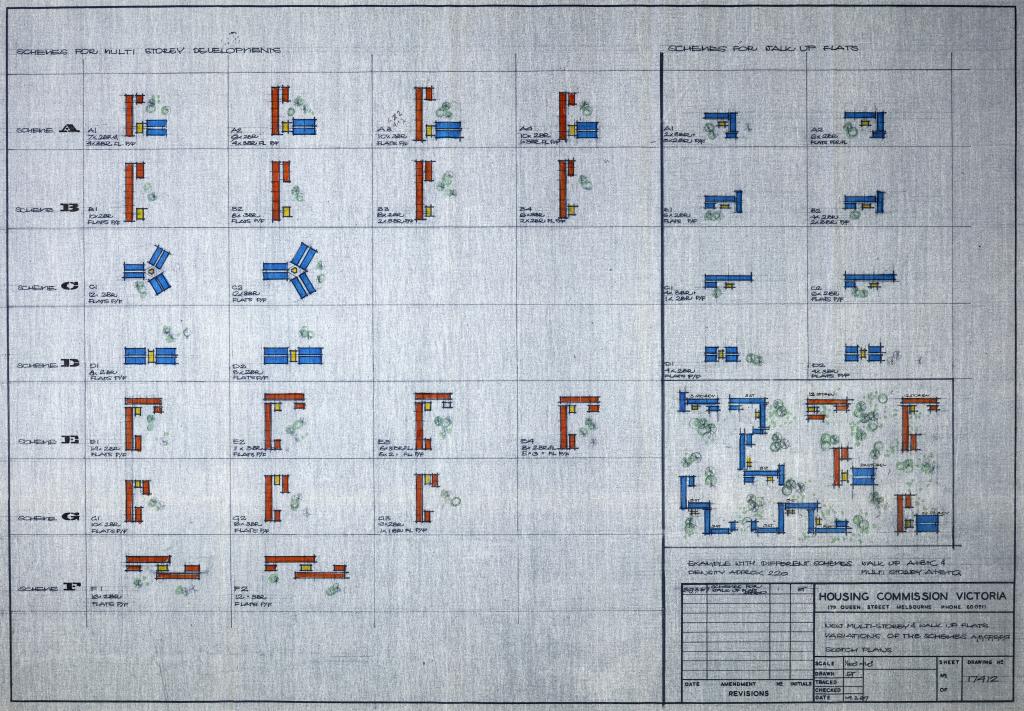

Even prior to the completion of this first Z-block, the HCV had begun developing a typography of the kinds of standard configurations it wanted to build, including types that closely resembled the floorplans built at Debney Meadows (see type F, Figure 6). The typology clearly shows that the HCV wanted to create a variety of standard forms that it could roll out to large numbers of sites across the city in various combinations. The correspondence accompanying the typology shows that Debney Meadows was already figuring as a benchmark in the ongoing process of refining the typology, with the aim of increasing efficiency and predictability in rolling out the design simultaneously across multiple sites.[15] Although the reality was much less varied (the basic Z-block came to be replicated many times in most of the later HCV developments), the towers and flats were all solid, affordable and generously sized with ample natural light, and they continue to stand to this day. Many recently built high-rise apartments produced by private developers offer much less in contrast.

Figure 6: Schemes for multi-storey and walk-up developments, March 1963. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 73, File F8 Flats (Multi-Storey), Drawing no. 17412.

Carlton Comprehensive Redevelopment Area

From 1938 to 1956, the HCV built around 32,000 units that were mostly single-family rental homes. Remarkable as this was as a program of social housing, the HCV considered it to be inadequate to the aim of substantially improving existing houses or replacing slum housing in the inner city. This was despite evidence that some of the areas that had once been considered problematic (such as Carlton) were spontaneously undergoing improvements and small-scale redevelopments.[16]

For instance, in 1951, the row of terrace houses at 100–108 Drummond Street was being converted by a private developer into a complex of 20 apartments with a mix of private dwellings with shared communal facilities (kitchen, bathrooms, laundries). Two memos written by HCV Secretary JH Davey, who visited the site with Housing Minister Ivan A Swinburne, note the condition of the properties and state concerns about the possible risks of relying on this kind of redevelopment. While these buildings were not slums as such, they were clearly in a poor state of repair and required significant improvements. The core buildings were structurally solid but features like verandahs, balconies and outbuildings were dilapidated and in need of repair. The concern was that many such buildings could easily become slums if they were divided into small apartments with higher densities, particularly in the absence of any substantial investment in repair and improvements.[17]

Figure 7: The street frontages (left) and backyards (right) of 100–108 Drummond Street, Carlton. Photographs documenting inspection on 8 August 1951 by HCV Secretary JH Davey and Housing Minister Ivan A Swinburne, PROV, VPRS 1811/P0, Unit 114, File S14 Slum Reclamation General File.

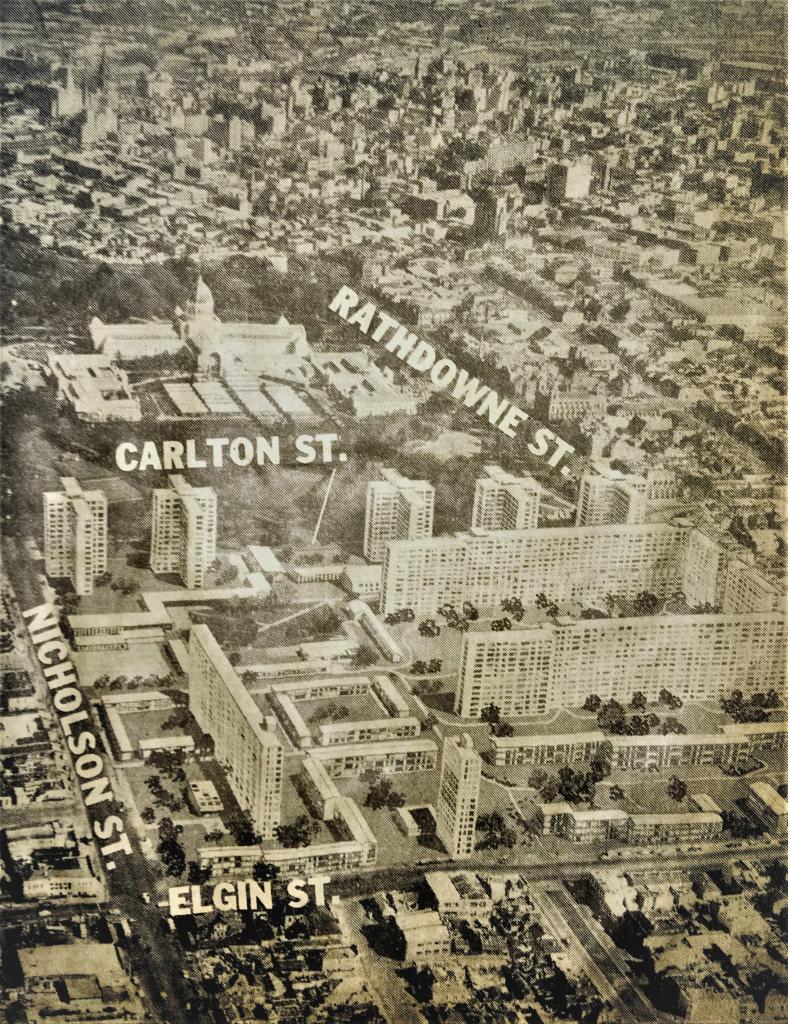

From 1956 a policy shift took place that encouraged more home ownership and focused on ‘Slum Reclamation’ projects in which higher densities of up to 200 people per acre were touted, requiring the building of flats of different configurations, from walk-ups to high-rise elevator blocks. As Peter Mills has argued, in the early 1960s this renewed effort to tackle slum reclamation was merged with a broader aim to undertake widespread urban renewal in which high-rise towers would figure prominently to achieve the densities that would justify the cost of land acquisition. These factors combined to drive all HCV proposals from 1965 towards high-rise-only estates. Large swathes of inner Melbourne were to be remade and modernised at greater densities and would involve both public and private housing estates (see Figure 8 for an early rendering of this imagined new Melbourne urbanism).[18]

Figure 8: Photomontage of a 31-acre redevelopment north of the Exhibition Gardens to accommodate 7,000 people, prepared by Melbourne architects Noel O’Connor and Carl Hammerschmidt, published in the Herald, 6 March 1958, found in MMBW news clippings scrapbook, PROV VPRS 8609/P21, Unit 318. Thanks to Peter Mills for bringing this image to my attention.

The new HCV housing was aimed at people who would be displaced by the clearance of slum areas and/or those on low incomes. A survey in 1960 estimated that at least 1,000 acres of ‘run-down’ housing existed in the metropolitan area; subsequently, the HCV replaced about 22 acres per year of the worst affected parts. Compulsory acquisitions were part of this approach in locations deemed to be ‘Reclamation Areas’. To make inner-city land purchases economically viable, high densities were required, even though, on the ground, much of the land would be open space of some kind (up to 80 per cent), including landscaped gardens, car parks, playgrounds and tree plantings.

The HCV’s focus on ‘Slum Reclamation’ was met with fierce community opposition in many of the large inner-city areas earmarked for demolition. Had the HCV’s initial vision been realised, whole inner-city neighbourhoods would have been demolished and rebuilt. Unlike Debney Meadows at Flemington, which was relatively modest in scale, did not involve large-scale demolition and went ahead without any resistance, so-called slum reclamation involved displacing whole residential neighbourhoods and so was highly controversial.

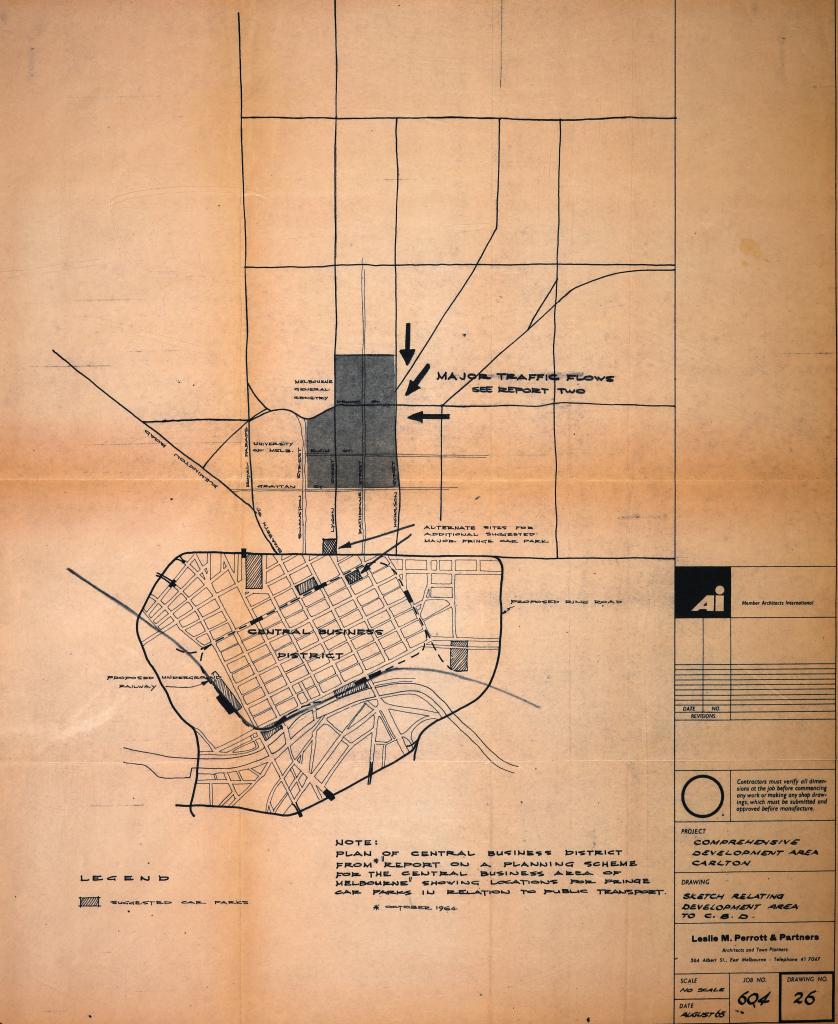

Figure 9: Plan showing the scale and position of the Comprehensive Development Area Carlton relative to the Melbourne CBD, prepared by Leslie M Perrott & Partners for Housing Commission Victoria, August 1965. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, Item C38 Carlton Comprehensive, drawing no. 26.

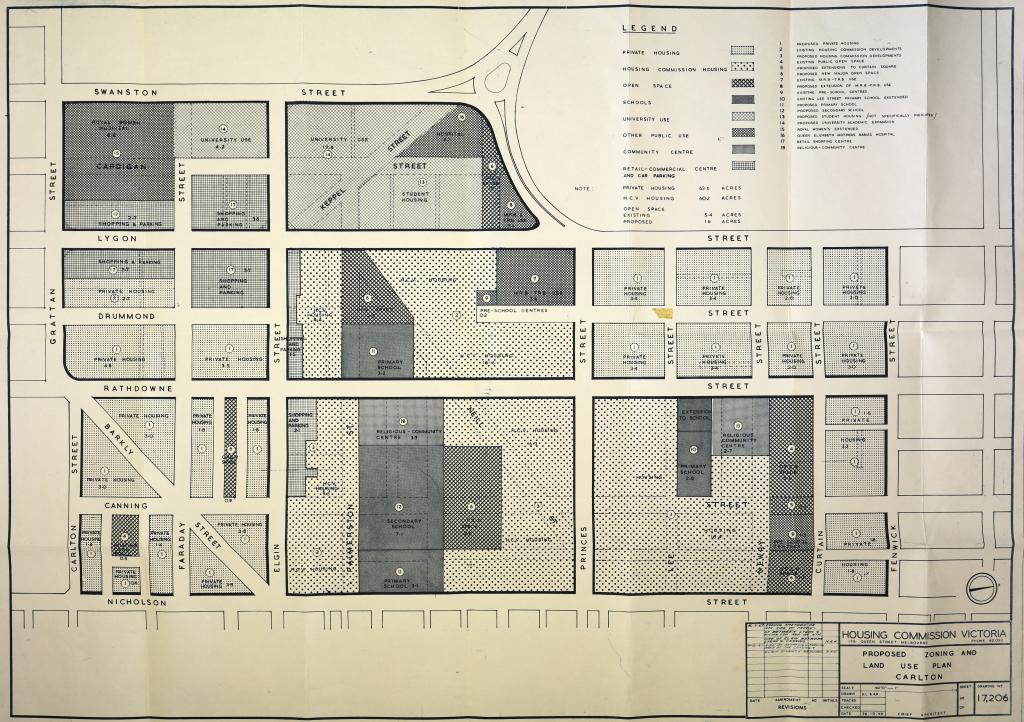

The proposed clearance areas were to be massive. In the case of the Carlton Comprehensive Development Area (Carlton CDA), which was the only one that was ever really fleshed out, more than half of Carlton and a large portion of North Carlton—an area extending north from Grattan Street to Fenwick Street, and from Swanston Street to Nicholson Street (see Figures 9 and 10)—would have been demolished and rebuilt through a combination of HCV and private development. The HCV plan, developed by consultant architects and town planners Leslie M Perrott & Partners, recommended a suburb-wide reconfiguration. Some streets would have been removed completely and the now iconic Lygon Street shopping and restaurant strip (which, even at the time, had a distinctly Italian and bohemian flavour) would have been entirely demolished. The shopping strip was characterised as ‘unsuitable for contemporary traffic conditions and marketing techniques’, and the shops themselves as:

inefficient of land use, disjointed, confusing and socially and aesthetically unsatisfactory … Accordingly, while we are conscious of the character and significance to the old Carlton environment of the Lygon Street [shops] and other [commercial] groups we have no option but to plan to completely replace them with facilities that will complement the total development proposals.[19]

A multi-level complex of shops and carparks would replace the shopping strip, extending from Lygon to Rathdowne streets, and from Elgin to Grattan streets.[20] Other land uses would have included both public housing (multi-level and high-rise constructed by the HCV) and private estates created by interested developers. Land was also set aside for new government administration buildings, schools, open space, university and hospital expansions and other facilities.

Figure 10: Plan showing proposed zoning and land use in the Carlton Comprehensive Development Area, Housing Commission Victoria, October 1966. North is to the left. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, Item C38 Carlton Comprehensive, drawing no. 17206.

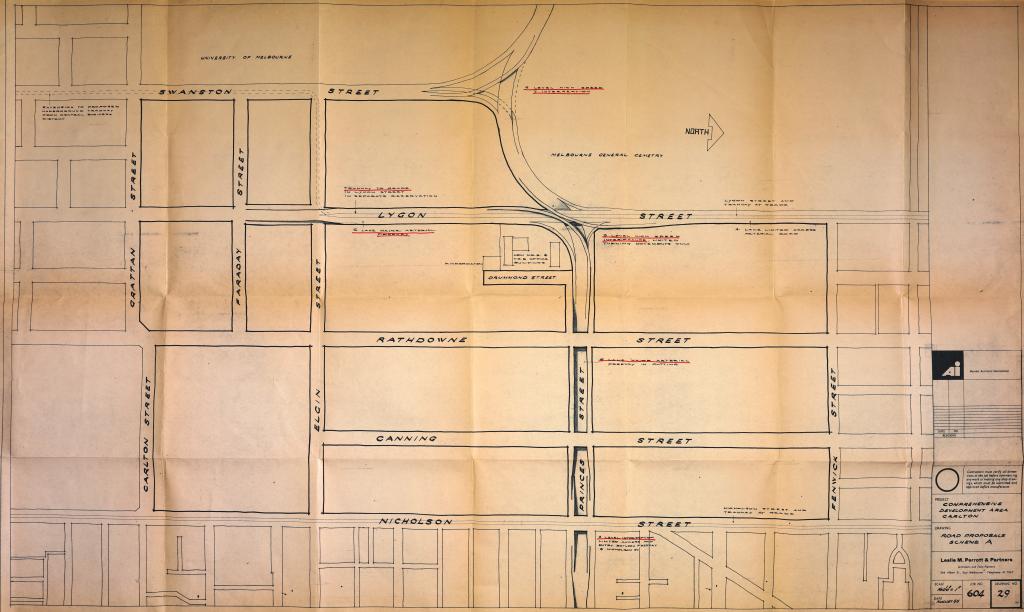

As part of the overall planning effort, the consultants hired by the HCV prepared new road plans to deal with the increased traffic requirements for the area. Several schemes were proposed with different major road configurations—all of them envisaged major arterial road expansions and huge new interchanges. Though these were only schemes and options for consideration, each seemed to make provision for a new major east–west arterial/freeway along Princes Street. At the time, a major transportation plan was in development for the city that included an extensive and interlocking freeway network. It is, therefore, not surprising that road schemes produced for the HCV made provision for such a freeway. As documents in the transportation planning files clearly show, the Eastern Freeway was originally envisioned as continuing past Hoddle Street (where it currently terminates) through Clifton Hill, Collingwood, Carlton, Parkville and beyond.[21]

In the example shown in Figure 11, Road Proposals Scheme A, a six-lane freeway in a trench would have replaced Princes Street, extending west from the end of Alexandra Parade. Bridges would have been constructed at Nicholson, Canning and Rathdowne streets. Nicholson Street would have had ramps to reach the freeway trench below. At the intersection with Lygon Street, a three-level interchange with various flyover ramps would have been created adjacent to the Melbourne General Cemetery, and part of Lygon Street would have been converted to a six-lane arterial road. An intersection at Swanston Street would have seen a two-level interchange with flyover ramps created between Newman and Queen’s colleges at the north end of the University of Melbourne and the southern boundary of the cemetery. As Leslie M Perrott stated in a paper presented to the Joint Urban Seminar held at the Australian National University in 1966, the approach to be taken on the Carlton CDA constituted a move away from simple slum reclamation to a more comprehensive urban renewal approach that would focus on ‘the problems of obsolescence and congestion’ that had generated ‘the poorness of our urban environment’.[22]

Figure 11: Plan showing Road Proposals Scheme A of the Comprehensive Development Area Carlton, prepared by Leslie M Perrott & Partners for Housing Commission Victoria, August 1965. PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, Item C38 Carlton Comprehensive, drawing no. 29.

While preparations commenced for building three additional high-rise towers at the Debney Estate in 1966, meetings were being held by the HCV and other stakeholder agencies in regard to the future of Carlton.[23] The MMBW, the City of Melbourne, the Town and Country Planning Board, the Hospitals and Charities Commission, the Department of Education and the Melbourne Transportation Committee (which itself was overseeing the development of major freeway plans for the city) were all represented in these meetings and consultations.

Following discussions with the HCV’s technical committee, some of the representatives of these agencies began to express reservations about the scale of the proposal being put forward by Leslie M Perrott & Partners on behalf of the HCV. Most of these agencies had, for their own reasons, been willing participants in progressing HCV’s other projects. In particular, the MMBW, although generally in favour of major urban renewal plans for the inner city that were supplemental to the Metropolitan Planning Scheme, baulked at the scale of the demolitions that were being put forward. Further, its representatives thought that the proposed urban densities of 200 people per acre in HCV developments and 100–120 per acre for private housing development were too high.

In a meeting with the technical committee addressing Report 4 of the consultants in September 1966, Chief Planner Alistair Hepburn and Senior Planning Officer Mr Harris of the MMBW asserted that there was no justification for accepting:

the proposition that the CDA/Carlton should be planned for total redevelopment rather than on the basis that whilst the majority of areas may at some time need to be demolished and redeveloped nevertheless there may be some section of sufficient quality that they should be permanently retained in their present or rehabilitated condition.[24]

The MMBW felt that other areas in inner Melbourne were in greater need of redevelopment but acknowledged that various factors (hospitals and university expansions and education needs in the area as well as traffic congestion and the ‘desirability of revising the road network’) combined to make Carlton a compelling case for a ‘pilot study’. Interestingly, the MMBW’s representatives defended the shopping strip, and urged that it be retained, ‘taking into account the requirements of the present [migrant] population in the area’. Concern was also expressed that ‘Carlton’s present attraction’ and ‘the whole fabric of the site will be lost if the scheme is implemented in its present form’. In short, Hepburn said that while the MMBW ‘was in favour of something being done in Carlton’, it did not think ‘such a “wholesale” scheme’ was warranted—especially not one that involved the whole area being pulled down.[25]

The scale of the proposed reconfiguration of an iconic inner-city suburb such as Carlton is almost incomprehensible for Melburnians today. The ambition of the plan, which would have unfolded over 15–20 years, was to literally demolish and rebuild most of a suburb along ‘modernist’, planned lines. In May 1965, Frank J Foy, the general secretary of the Real Estate and Stock Institute of Victoria, produced a report that summarised numerous misgivings about the proposals that were already taking shape. Foy observed that, while:

this section of Carlton … has some bad pockets, [it] is not by any means a slum area and although there are some properties which are run down and have not been the subject of re-development, very many others have been greatly improved and an amount of redevelopment has taken place by the erection of flats and other buildings.[26]

In other words, the planned urban renewal seemed to be missing the existing urban renewal that was already taking place spontaneously, making the area substantially less slum like. In addition, the shopping strip, although it admittedly contained some run-down properties, was also improving. If the shopping strip was subject to large-scale demolition ‘in favour of one central area, it is likely that a number of shop-keepers will lose at least a substantial portion of the Goodwill they have built up over the years’, Foy noted. He was concerned that the scale of the plans would have a detrimental impact on property values and would stifle much of the spontaneous regeneration and investment that was already taking place in the area, disrupting rather than engendering business activity. He recommended that the HCV’s development activities be limited to the area bound by Lygon, Princes, Nicholson and Palmerston streets.

In the end, less than half of the area proposed by Foy was redeveloped by the HCV. It is difficult to determine why the HCV’s initial plans for Carlton were so comprehensive: perhaps it was a habit of thinking that stretched back to the days when the HCV was first created to alleviate substandard housing and to prevent the emergence of true slums. As some of those voicing concerns at the time noted, Carlton was far from rife with slum dwellings. Perhaps the real driver, as alluded to in some of the observations of the MMBW representatives and others, was that there were other ‘pressures’ on the area that needed to be addressed: expansion of the university and hospital, more schools, and better traffic and road network management. Perhaps it was all of the above—a combination of interests and players—that made Carlton a compelling site for enacting a technocratic form of modernism: remaking a whole suburb in the name of progress.

Conclusion

The HCV correspondence files provide insight into the thinking and effort behind a number of consequential urban planning and infrastructure projects during a time of great social and demographic change in inner Melbourne. They document an ambitious housing program that had to make compromises with local residents and communities that rejected the characterisation of their homes as slums and resisted the demolition of their neighbourhoods. That compromise resulted in the distinctive landscape of today’s inner city, where high-density towers for people on low incomes and limited means dwell inside some of Melbourne’s most beautifully preserved heritage suburbs. The plans and activities of agencies such as the HCV allow us to glimpse a time in which strong government intervention on the supply side of housing was still taken seriously as a possibility. For all the overreach and drawbacks of some of the grander plans for urban redevelopment in areas like Carlton, revisiting the approach taken during this era reminds us that there may still be other and more effective ways to address housing affordability and urban planning than those that have prevailed in recent times in Melbourne.

Endnotes

[1] Guy Rundle, ‘Winter is here for Melbourne’s CBD as city runs out of spirit and vision’, Crikey, 14 April 2021, available at <https://www.crikey.com.au/2021/04/14/melbourne-cbd-planning-covid/>, accessed 5 May 2021.

[2] Kate Shaw, ‘Murky waters: the politics of Melbourne’s waterfront regeneration projects’, in K Ruming (ed.), Urban regeneration in Australia: policies, processes and projects of contemporary urban change, Routledge, New York, 2018, esp. p. 135. See also Alan March, The democratic plan: analysis and diagnosis, Ashgate, Burlington, 2012, p. 64.

[3] Michael Buxton, ‘When system becomes strategy: next steps in Victorian neoliberal planning’, 8th State of Australian Cities National Conference, 28–30 November 2017, Adelaide; Brendan Gleeson & Nicholas Low, ‘Revaluing planning: rolling back neo-liberalism in Australia’, Progress in Planning, vol. 53, no. 2, 2000, pp. 83–164; Mark Beeson & Ann Firth, ‘Neoliberalism as a political rationality: Australian public policy since the 1980s’, Journal of Sociology, vol. 34, no. 3, 1998, pp. 215–231.

[4] Renate Howe, David Nichols & Graeme Davison, Trendyville: the battle for Australia’s inner cities, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2014, p. 1.

[5] These shifting demographics and the cultural clash between the emerging inner-city communities of Melbourne and Victoria’s major infrastructure bodies in the 1960s and 1970s has been covered by the author elsewhere, see Sebastian Gurciullo, ‘Deleting Freeways: community opposition to inner urban arterial roads in the 1970s’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 18, 2020, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2020/deleting-freeways>, accessed 23 July 2021.

[6] For instance, see PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 72, file F6 Flats (General), Unit 65, file E14 Equipment for Houses and Flats.

[7] ‘Board’s chief planner wants Debney’s for public recreation’, Age, 4 February 1958, p. 3; ‘Council row over Debney’s’, Age, 25 February 1958, p. 1; ‘Housing and Parks only for Debney’s Paddock’, Age, 21 May 1963, p. 5.

[8] HR Petty, Minister for Housing, to Secretary HCV, 21 July 1958 and 11 September 1958, PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 73, File F8 Flats Multi-Storey, Unit 73. This was brought to my attention by Peter Mills, Refabricating the towers: the genesis of the Victorian Housing Commission’s high-rise estates to 1969, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Faculty of Arts, Monash University, 2020, p. 149.

[9] The one exception seems to be the opposition voiced by the Federation of Co-operative Housing Societies, which claimed that the costs associated with the high-rise plan ‘would be a ridiculous price and a scandalous waste of funds’, see ‘Protest move on Debney’s flats’, Sun, 23 May 1959, found in an MMBW news clipping scrapbook, PROV, VPRS 8609/P21 Historical Records Collection, Unit 318.

[10] Mills, Refabricating the towers, p. 8.

[11] Rory Hyde, ‘ARM Architecture and the big public’, ArchitectureAU, 7 November 2016, available at <https://architectureau.com/articles/arm-architecture-and-the-big-public/>, accessed 1 May 2022.

[12] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 58, File D7 Debney Meadows Estate Part 1.

[13] PROV, VPRS 1811/P0, Unit 29, File D5 Debney Meadows.

[14] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 59, File D7 Debney Meadows Estate – Part 1, official opening brochure

[15] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 73, File F8 Flats (Multi-Storey).

[16] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 141, File P40 Publications, The Housing Commission, Victoria, 1965.

[17] PROV, VPRS 1811/P0, Unit 114, File S14 Slum Reclamation General File, memos from JH Davey, Secretary, Housing Commission, dated 10 August 1951 and 22 February 1952.

[18] Peter Mills, Refabricating the towers, chapters 4–7.

[19] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, File C38 Carlton Comprehensive Part 1, Report 2, 9 April 1965, p. 3.

[20] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, File C38 Carlton Comprehensive Part 1, Report 2, 9 April 1965, p. 6.

[21] On the development of the freeway plans for this area see Gurciullo, ‘Deleting freeways’.

[22] LM Perrott, ‘Carlton Redevelopment’, in PN Troy (ed.), Urban Redevelopment in Australia, Papers presented to a Joint Urban Seminar held at the Australian National University, October and December 1966, Research School of Social Sciences, Urban Research Unit, Australian National University, 1967, pp. 218–219. Perrott was invoking the findings of a report on ‘Urban redevelopment’ by a committee appointed by the Civic Trust in Great Britain.

[23] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0: Unit 47, File C38 Carlton Comprehensive; Units 58 and 59, File D7 Debney Meadows Estate (Parts 1 and 2).

[24] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, File C38 Carlton Comprehensive, meeting minutes 15 September 1966.

[25] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, File C38 Carlton Comprehensive, meeting minutes 15 September 1966.

[26] PROV, VPRS 1808/P0, Unit 47, File C38 Carlton Comprehensive Part 1, Frank J Foy to HCV, 21 May 1965.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples