Author: Natasha Cantwell

Communications & Public Programming Officer

Please note that historical quotes in this article include outdated terms that are not acceptable today.

Victoria’s journey toward anti-discrimination protections has been a decades-long struggle marked by political debate, public lobbying, and shifting social attitudes. Grassroots activism culminated in the Equal Opportunity Act 1977 and pushed forward its successive amendments. As the fight for fairness and equality continues, we look back at recently released Cabinet-in-Confidence files from 1982-1992 and reflect on three early developments in Victoria’s Equal Opportunity Act that helped lay the foundations for a more inclusive State.

Women

With job ads split by gender, married women pushed out of the workforce, and single women denied basic rights like bank loans or tenancy agreements, it’s little wonder that by the 1970s Victoria’s women had had enough. As the 1985 Ministerial Statement on Women observed, inequality had “become entrenched in the attitudes and practices of our society, until women themselves challenged it.”(1)

The decade saw relentless activism from women’s groups, most notably the Women’s Electoral Lobby (WEL), whose non-confrontational, data-driven and policy-literate campaigning helped bring these injustices into mainstream view. WEL’s comprehensive surveys and reports supplied the government with the evidence needed to recognise the scale of discrimination and its repercussions across Victoria. They also shaped the intellectual framework for the Equal Opportunity Commission, arguing that legislation would be ineffective unless supported by an independent body with the authority to enforce anti-discrimination protections.

Their work paved the way for the Equal Opportunity Act of 1977, which outlawed discrimination based on sex or marital status in Victoria. Its impact was swiftly tested by Deborah Lawrie, the first woman to bring a case before the board after being denied entry to Ansett’s pilot training program - despite outqualifying her male counterparts.

Company founder Reg Ansett made irrational arguments against hiring female pilots, claiming that menstrual cycles made women medically unfit once a month, that they were prone to panicking, and even citing the lack of women’s toilets near the flight simulator. Lawrie recalled a comment about her earrings, as if they were “a permanent fixture and would impede my escape from an aircraft”.(2)

Ansett contested the case at every turn - lodging appeals to both the Supreme Court and the High Court and attempting to leverage its political connections. But in March 1980, the High Court ruled the airline’s actions unlawful, setting a precedent that would shape future discrimination cases, and allowing Lawrie to get on with her life and her chosen career.

Throughout the 1980s, the Victorian State Government sought to “address the imbalance that has arisen from historical neglect”(3) by implementing measures such as promoting girls’ participation in science and maths, outlawing sexual harassment, and extending extra support to migrant women.

But achieving gender equality called for a deep societal shift. Internal documents admitted that change was “slow in coming and sometimes painful,” particularly in the workplace, as,

“it is not only women’s lives which are changing, but men’s lives as well. Men have needed to adjust to the idea of working alongside women, sometimes with a woman in charge.”(4)

In its 1987 Statement on Women’s Employment,(5) the government conceded that although more women were joining the workforce, they remained concentrated in low-paid, low-status roles with limited prospects for advancement. Victoria’s gender pay gap was stark in the 1980s, sitting at around 23%. It wasn’t an issue that could be resolved in a single decade, and it remains a priority today, with the gap still about 11%.(6) Even so, the reforms of that era laid crucial foundations for long-term change.

In 2025, Deborah Lawrie, now the world’s most experienced female airline pilot, reflected on her landmark case, noting that she hadn’t grasped its importance at the time:

“But the reactions I get these days, I can look back now and see how significant it was.”(7)

Lawrie’s triumph, built on the reforms forged by activists before her, continues to shape Victoria’s pursuit of gender equality today.

Disability

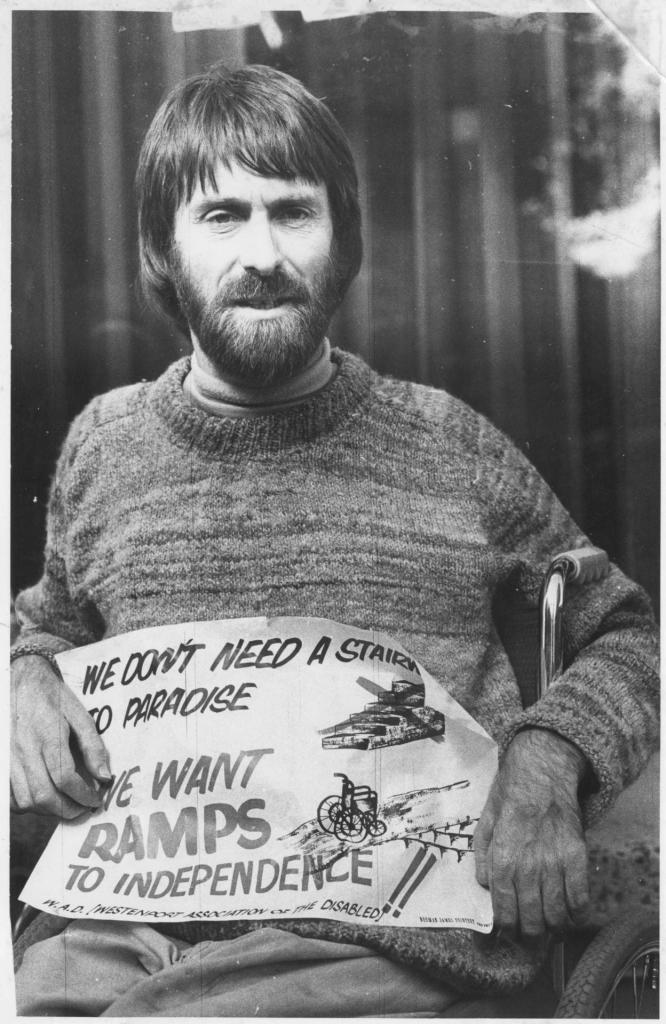

In his early twenties, Geoff Bell was forced to live in a nursing home - the only option available to a young person with quadriplegia in the 1960s. At the time, people with disability were largely overlooked by governments: their needs sidelined and their voices excluded from policy discussions, spoken for instead by service providers.

Refusing to be ignored, Bell wrote to the Minister for Social Security, Bill Hayden, urging for the development of specialised support services. The letter’s tabling in Federal Parliament signalled the first step in Bell’s emergence as a leading figure in the growing disability rights movement in Melbourne and across Australia.

In 1978, Bell and nine other members of the Disabled People’s Action Forum (DPAF) blockaded a Medibank entrance, demanding action on the widespread inaccessibility of public buildings. Bell told the media the protest aimed “to show the architectural barriers we have to put up with. Medibank is supposed to be a service and yet it is stopping our needs to transact our personal business.”(8)

The infamous action, along with Bell’s memorable poster - “We don’t need a staircase to paradise. We want ramps to independence” - drew public attention to the everyday discrimination faced by Victorians with disability.

But as Bell’s friend and fellow advocate Maree Ireland reflected,

“we have all sat at demonstrations with a sign, but heading home you can sometimes wonder if you have made a difference. But what set Geoff apart was his ability to get his ideas before politicians.”(9)

A prolific letter writer over the decades, Bell continued to use his lived experience to help politicians grasp the need for participation and inclusion for people with disability in all aspects of community life. Through the efforts of Bell and activists worldwide, disability in the 1980s began to be understood not as an individual medical issue, but as a human rights issue shaped by social barriers.

Institutions and governments began to take notice. In 1981, the United Nations declared the International Year of Disabled Persons, and in 1982 the Victorian Government introduced the Handicapped Persons Anti-Discrimination Bill. The Second Reading Notes(10) acknowledged:

“For too long, physically handicapped people have suffered discrimination in almost every area of community living. Now, so far as is possible, the law will require that handicapped persons be treated like all other members of the community.”

The notes also recognised that market forces “by their very nature discriminate against persons having any disadvantage,”(11) reinforcing the need for legislation to ensure equitable employment opportunities.

Coming into effect in 1983 as the Equal Opportunity (Discrimination against Disabled Persons) Act, the legislation made it unlawful to discriminate against people with disability in employment, education, accommodation, and access to goods and services. For example, it prevented landlords from refusing to rent to a person because they had a guide dog. The Act had limitations - particularly around the access of public places - but crucially, by establishing a legal foundation for non-discrimination, accessibility was no longer a matter of charity or goodwill. It became increasingly a legal and social expectation.

Bell passed away in 2008, but Melbourne’s disability rights movement is still strong today, with activists continuing to protest issues such as the limited number of accessible tram stops.

Sexual orientation

In 1974, Jamie Gardiner OAM returned to Melbourne after studying in London, eager to channel his experience in the Gay Rights movement into local action. At the time, sex between men was still a criminal offence in Victoria, and one of Gardiner’s most impactful early actions was with the Homosexual Law Reform Coalition (HLRC). Gardiner recalls:

“Changing the law was absolutely the first key to changing our position in society, because everything that we did was either secret or dangerous.”(12)

Through persistent, strategic lobbying, the HLRC helped secure long-overdue legislative change. But while the Crimes (Sexual Offences) Act 1980 nominally decriminalised homosexual sex, a conservative faction within the Liberal Party added the deliberately ambiguous offence of soliciting for “immoral sexual purposes.”

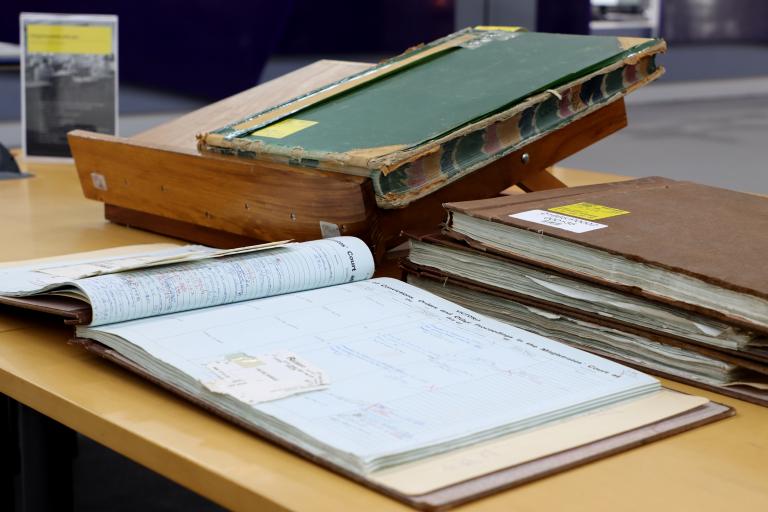

In effect, it gave police and magistrates who deemed homosexuality ‘immoral’ licence to continue charging and convicting gay men. It took another six years - and sustained pressure from queer activists - before this provision was finally repealed in 1986. Gardiner stresses that numerous men were punished because of this loophole. His research into Public Record Office Victoria’s (PROV) court ledgers from that period reveals the names of men who were sentenced unjustly between 1981 and 1986:

“In my first two or three hours at PROV I found an example, this poor chap was sentenced to a fine, which he paid.”(13)

Gardiner’s research at PROV contributed to the development of Victoria’s 2015 Expungement Scheme, a significant step towards addressing past harms by formally erasing historical convictions for homosexual activity.

From activism to legislative reform

From grassroots activist to Equal Opportunity Commissioner advisor, the 1980s and 90s saw Gardiner’s expertise and legal insight became invaluable to the Victorian Government as Labor pushed for ‘sexual orientation’ and ‘gender identity’ to be recognised as protected attributes under the Equal Opportunity Act.

After protracted parliamentary debates in 1984 and again in 1985, those amendments were blocked by the opposition. A 1992 Cabinet-in-Confidence paper by Deputy Premier and Attorney-General Jim Kennan reflected on those earlier attempts, noting:

“Members of the National Party opposed the legislation as a matter of principle, arguing, for example, that a person should be permitted to discriminate against homosexuals.”(14)

But by the early 1990s, the social and political landscape had shifted dramatically. Many of the legislation’s fiercest parliamentary opponents had moved on, public sentiment was evolving, and even the Archbishop of Melbourne had voiced support.

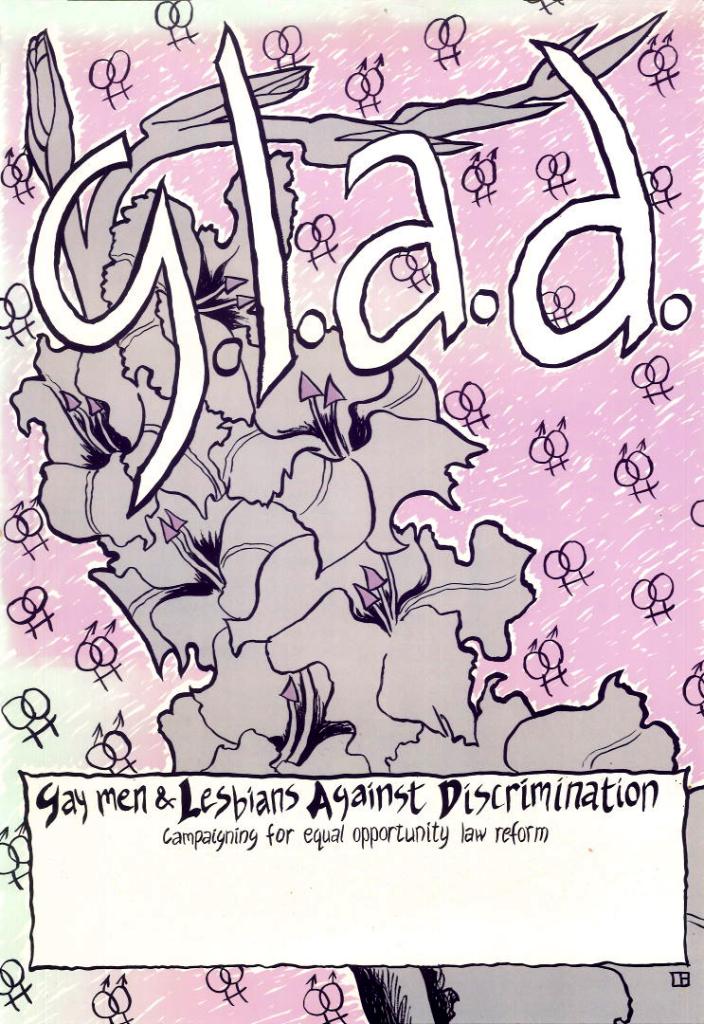

Sensing a genuine opportunity to secure legal protection for queer people, the activist group Gay Men and Lesbians Against Discrimination (GLAD) formed with a clear purpose: to finally see the reforms passed. GLAD mobilised the queer community, allies, and human rights advocates to lobby the government and show the depth of public backing for the proposal. They also worked to ensure the legislation would genuinely respond to community needs, conducting a wide-ranging survey across Victoria to document queer people’s experiences of discrimination.

Despite the growing support, opposition persisted, notably from the Scouts Association, which argued that “homosexuals posed a risk to young boys.”(15) Kennan firmly rejected that claim, stating: “It embraces a negative stereotype of homosexuals, which is completely contrary to the purpose of anti-discrimination legislation. It confuses homosexuality with paedophilia.”

The Victorian Government also noted that similar reforms in South Australia and Queensland had left loopholes, such as allowing “reasonable” discrimination based on how a person dressed as an expression of their sexuality. Determined to avoid such gaps, Labor continued to fight in Parliament for comprehensive protections.

In 1995, the law finally passed, though with the watered-down wording ‘lawful sexual activity’. It wasn’t until 2000 that the Act was updated to explicitly include ‘sexual orientation’ and ‘gender identity’.

Gardiner continues his human rights advocacy today, most recently contributing to the Victorian government’s expansion of protections against hate speech. From 30 June 2026, these laws will extend beyond race and religion to also cover disability, gender identity, sex, sex characteristics, and sexual orientation.

“When I first met other gay people,” Gardiner reflects, “the idea of changing the world wasn’t really there.” That shifted as momentum built throughout the 1970s to 90s, and people began to realise the power of community action.

“We collectively, through chains of action, have changed the world. We’ve changed Victoria, we’ve changed Australia, and our colleagues in other countries are doing the same.”(16)

The records referenced in this article were previously closed under Section 10(1) of the Public Records Act 1973 (Vic) which protects sensitive information like cabinet deliberations, Ministerial submissions, or internal processes of government bodies. 2026 marks the first year that records closed under this Section of the Act have been opened and made available to the public. You can read more about these records here: https://prov.vic.gov.au/victorian-cabinet-records-1982-92#2989_1992

Thank you to Jamie Gardiner OAM for speaking with us for this article.

Continue exploring Victoria’s political evolution

Discover more in-depth details of the Cain-Kirner era by delving into the Cabinet records.

Endnotes

1, 3, 4.) PROV, VPRS 11944, P1, 000031-1390.

2.) “Game changers: Australia's first female pilot for a major airline” (2017, February 24). SBS News. Retrieved from: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/insight/article/game-changers-australias-first-female-pilot-for-a-major-airline/o25jmhmph

5.) PROV, VPRS 11944, P1, 000043-1970

6.) “The ABS data gender pay gap” (n.d. circa 2025, August 14). Workplace Gender Equality Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.wgea.gov.au/data-statistics/ABS-gender-pay-gap-data

7.) “Deborah Lawrie: The Fight to Fly” (2025, April 10). UNSW Centre for Ideas. Retrieved from: https://unswcentreforideas.com/article/deborah-lawrie-fight-fly

8.) “People With Disability Australian Protest Timeline” (2023). Commons Library. Retrieved from: https://commonslibrary.org/people-with-disability-australian-protest-timeline

9.) “Archives of the disability rights movement” (2019, April 16). The University of Melbourne. Retrieved from: https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/librarycollections/2019/04/16/1810-2/

10, 11.) PROV, VPRS 11944, P1, 000005-321

12, 16.) “Quests By Community: Historic Challenges, Jamie Gardiner OAM, Human Rights Activist” (2024, July 26). Bent TV. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ynTFeqgrCVI

13.) Jamie Gardiner OAM interview by Natasha Cantwell at PROV (2025, November 12)

14, 15.) PROV, VPRS 11944, P1, 000133-8146

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples