Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

Please be aware that this article contains information about gun violence and may be upsetting for some readers.

The Russell Street bombing, Hoddle and Queen Street massacres, Walsh Street police shootings, and the crimes of Mr Cruel… It’s the stuff nightmares are made of.

Violent crime in the 1980s was a major concern within the Victorian community, particularly with gun violence on the rise.

A focus on gun crime

Across Australia, the statistics were dire. In 1987 there were six incidents of mass shootings, 97 homicides, 572 suicides, and 27 accidents all by firearm - an overall increase of 22.3% on 1975 figures.

Two of Australia’s six mass shootings in 1987 took place in Melbourne.

August saw 19-year-old Julian Knight take his Ruger rifle, M14 and Mossberg shotgun and open fire on Hoddle Street drivers and police. He killed seven people and injured 19 others.

Just four months later, 22-year-old Frank Vitkovic used a modified M1 to shoot office workers in the Australia Post building on Queen Street. He shot 13 people, killing eight.

It didn’t end there. The following year, October 1988, Constables Tynan and Eyre were shot and killed in South Yarra by an armed robbery gang.

While the John Cain state government got to work on firearm legislation reforms, criminal Gary David Webb proclaimed his desire to commit a mass murder bigger than Hoddle and Queen Streets combined.

Gun legislation

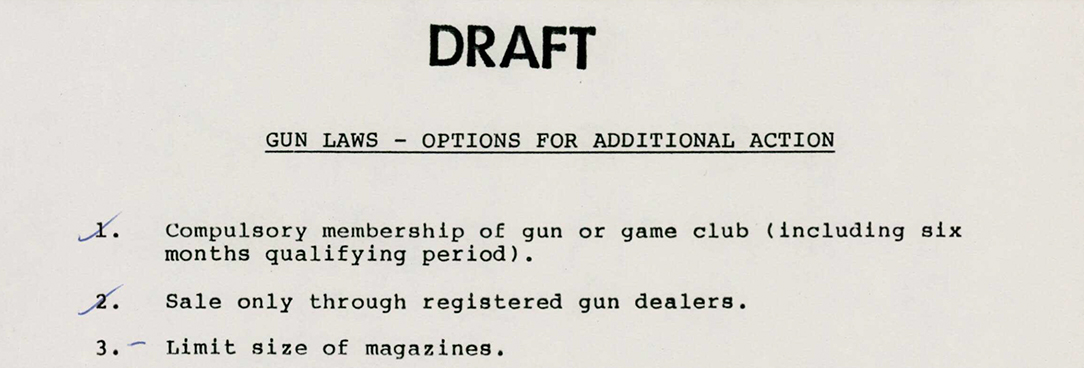

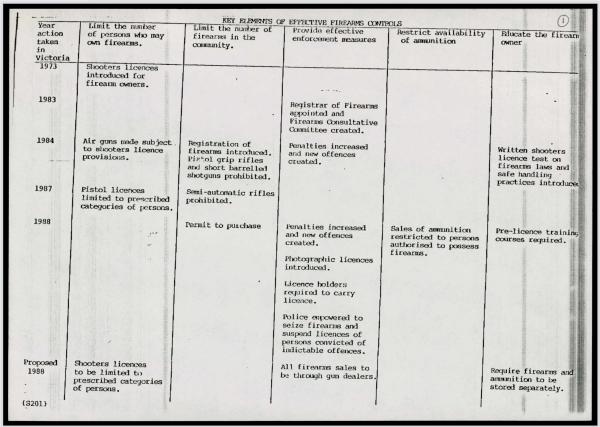

The government’s commitment to gun reform was first announced in 1981 as part of the ALP’s 1982 election priorities – five years before the mass killings that shocked Victoria.

“The party had spelled out detailed policies about registration and the licencing of shooters generally. These policies had been argued very widely during the 1982 election campaign. The real drive for the proposed changes in the law came from a positive, assertive demand by people within the party and outside who felt that the onus was on a labour government to do something about the growing number of firearms lying around a very large number of homes,” said John Cain Jr in Trials in Power.

The 1987-88 shootings solidified the government’s commitment.

The Cain government was determined to create a licensing and registration system, ensuring that gun owners would have to do more than simply pay a fee to obtain a firearm.

Historian and author of Under Fire: How Australia’s Violent History Led To Gun Control, Nick Brodie, told PROV that the public at the time was supportive.

“The Australian public by and large through most of its history has been very sympathetic to sensible, reactive, gun law control…But, by this point (the 1980s) there’s very vocal, organised, lobby groups so they attract a lot of the press attention and drive the discourse.”

This vocal opposition is evidenced within Cabinet records.

In a brief to the Premier, Julie Dawson of the Department of the Premier and Cabinet’s Justice Branch stated:

“The opposition’s main line of argument in opposing the Bill was that the Government was ‘grandstanding’ on the Hoddle Street killings and unreasonably interfering with the rights of certain groups to own and use firearms.”

In 1988, 30,000 gun-enthusiasts took to the streets to protest proposed regulations and Opposition leader Jeff Kennett warned the Herald that most semi-automatic gun owners would not part with them, leading to a black market.

“He (Mr Cain) is going to create a situation where there is massive civil disobedience,” said Kennett.

A memo to shooters from the Sporting Shooters Association of Australia declared:

“The Cain Labor Government has sought to deny shooters of their civil rights and has shamelessly attempted to use the firearm issues as a springboard for a Victorian State election.”

The government, undeterred, managed to ensure that Victoria had the tightest gun laws in Australia (for the time). Their Firearms (Prohibited Weapons) Regulations banned semi-automatics; and the Firearms (Amendment) Bill ensured licenses and registration of firearms with increased penalties for non-compliance.

A privilege not a right

John Cain said in an address to Cabinet in 1988:

“The (Firearms Amendment) Bill reflects widespread community concern with the large number of firearms in the community and the increasing frequency of their misuse…We are not so foolish as to believe that the implementation of the measures contained in this Bill will put an end to the criminal, the tragic, and the destructive use of firearms. Nor should it be inferred that the government queries the level of competence and responsibility among the great majority of Victorian gun-owners. We recognise that some people in the community have a legitimate need for guns and that others wish to use them for lawful recreational purposes. The Bill does not deny that legitimate needs exist. It does not seek to curb legitimate sporting activity. But it does demand that legitimacy be demonstrated…The Bill establishes emphatically that ownership of guns is not a right but a privilege. A privilege granted by the community to law-abiding citizens under very strict provisions.”

“Most alarming of all – to the government and to the people of Victoria – was the use on two separate occasions of semi-automatic weapons in acts of mass murder. There are about 210,000 of these rapid-fire rifles in Victoria. The government sees no real private need for them, but very considerable public menace… Owners of these rifles will be required to surrender them to the police, and the government will pay fair compensation for them.”

“This Bill does not seek to remove a single right. Rights which do not exist cannot be removed. Instead, the Bill will reinforce an existing right – the right of all Victorians to go about their daily lives in safety.”

While John Cain sought safety from guns in Victoria, an issue remained, as it does today: the difference in laws across jurisdictions.

“People could (still) get guns in one state and then simply move. That was one of the big underlying issues at that time,” explained Nick Brodie.

The proliferation of guns in Victoria

So, how did “210,000 rapid-fire rifles” end up in homes across Victoria? According to Brodie a series of social changes across the mid twentieth century led to increased gun possession in the humble home.

“There’d been a shift towards organised recreational shooting during the mid-20th century. You get to the point where the average recreational shooter can have access to semi-automatic firearms. Often because of relatively inexpensive imports from China. So, in that post-Vietnam period, the arms industry pivots. So, instead of selling guns to the army, they start selling to the recreational shooters. So, there’s more of those types of guns out there.”

For a long time, according to Brodie, the biggest issue of concern was accidental shootings in the home.

Then, as reforms across Australia stagnated, the worst kinds of weapons became more common in criminal shootings.

Gary David Webb legislation

By the end of the 1980s, one criminal in particular became the focus of legislation, as the government renewed its commitment to community safety and reducing gun violence.

Gary David (Webb) – sometimes spelt Garry – was a 34-year-old criminal serving a sentence for shooting a woman and policeman in Rye in 1980, seriously injuring them both. While incarcerated, he committed numerous acts of violence against other prisoners and officers - and threatened mass murder should he ever be released.

The Solicitor General wrote: “His history indicates that the threat is genuine and he has the ability to carry it out.”

The government took his threats so seriously that they began searching for means to keep him incarcerated beyond his 1990 release date. Psychiatrists could not agree on whether Gary David was mentally ill and so he could not be held under the Mental Health Act. And any change to the Act would take too long.

The Solicitor-General’s suggestion to the Premier stated:

“If a man is pointing a gun at you, neither the law nor common sense requires you to wait until he pulls the trigger. Gary David is a unique case. There has never been anybody like him. There is some suggestion that there are other dangerous people in the system, but I do not believe that they are anything like Gary David and I have heard no evidence to that effect…I would like to suggest that the proper answer is a Gary David Bill.”

And so, a Bill was created. The Community Protection Bill, known as the Gary David (Webb) Act, was passed in April 1990 to protect the community from one individual.

“The Bill at Cabinet provides for the detention of Garry David through proceedings instituted in the Supreme Court. The Bill will enable David to be detained in either a prison or mental health facility, and his detention will be reviewed by the court every 12 months. David’s detention will be continued for as long as he remains a threat to the community.” – Department of Premier and Cabinet Briefing Note.

In Cabinet documents opened on 1 January 2026, it was clear that the Cain government felt the need to protect the community outweighed the rights of the individual. Gary David (Webb) was held in J Ward at Aradale, Ararat, as a result.

The end justified the means

In the Melbourne University Law Review, academic David Wood criticised this “extraordinary piece of legislation.”

“…the Act runs counter to one of the principles generally included within the rule of law. Whatever else this notion may involve, it requires that laws be of general application, that individuals be subjected to the same law. David is patently to be subjected to a different law, a law that explicitly applies only to him. Someone else identical with him in all relevant respects (even those who present a far greater threat to the community) escapes the ambit of the Community Protection Act for no other reason than that that person is simply not Garry David.”

Wood further elaborates that, “No one is satisfied with the way the Garry David case was handled. It seems that the worst possible solution is the blatantly ad hoc legislation that the Victorian Government felt compelled to introduce. Despite the unprincipled nature of the Act, the Victorian Parliament was prepared to support it out of fear of the consequences. To them, the end justified the means.”

View the records: Victoria’s gun control laws revealed

On 1 January 2026, Cabinet records relating to gun reforms during the John Cain Jr era were officially opened. These documents shed new light on the debates, decisions, and policies that shaped Victoria’s approach to firearms legislation at the time.

Explore the Cabinet records now to see the sources behind this article. Records referenced here include:

- Premier’s Briefing Papers on Specific Issues, VPRS 11952 P1 Box 1 Guns

- Premier’s Briefing Papers on Specific Issues, VPRS 11952 P1 Box 1 Garry David Webb

Other references

- Violent Deaths and Firearms in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1996

- A One Man Dangerous Offenders Statute – The Community Protection Act 1990, By David Wood, 1990

- Trials in Power: Cain, Kirner and Victoria 1982-1992, Edited by Mark Considine and Brian Costar, 1992

Nick Brodie’s book, Under Fire: How Australia’s Violent History Led To Gun Control, is a comprehensive history of the role of guns across Australia.

Continue exploring Victoria’s political evolution

Discover more in-depth details of the Cain-Kirner era by delving into the Cabinet records.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples