Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

21 December 1934 at approximately 9.30pm, Footscray labourer William Henwood watched as a young woman walked with her baby and suitcase towards Richmond Suspension Bridge on the bank of the Yarra River. Half an hour later she walked past him again in the opposite direction, this time the baby wasn't with her.

In March the following year, Mary Alice Clara Stevens was sentenced to death for the murder of her baby, Leslie Neil Stevens.

In one of a series of Section 9 files now open as of January 2015, Mary Alice Clara Stevens petitioned the court for mercy. This is her story as told through the records found in that file.*

Early years

Mary Alice Clara Stevens was born on the 27th of February 1911 in Chiltern. She was one of eleven siblings, ranging in ages from eleven to thirty-five, and her father was an employee of the Albury Council. At school she did well obtaining a Merit Certificate before entering service in Albury at seventeen years of age.

It was here she met the man who would, some years later, become her fiancé. Transport driver Eugene Rollings courted Mary Alice for two years before proposing. However, Mary Alice decided she did not want to be tied down and so handed back the ring.

Soon after, she met Leonard Eames of Tribune Street. He was always well dressed and seemed decent. It wasn’t until Mary Alice became pregnant with his child that she discovered him to be a married man. She returned home to her parents. By her own admission to the Inspector General, her mother wasn't pleased to see her, but her father was good to her and made all the arrangements for her.

The birth of Leslie Neil Stevens

Leslie Neil Stevens was born on the 16th of November 1933 at the home of Mary Alice’s parents in Albury. Mother and baby were taken to the nearby private hospital where they stayed for 11 days before returning home for three weeks.

It was then that Mary Alice moved to Melbourne.

In her statement to police she explained:

“On 3rd January 1934 I took the baby to the City Mission Maternity Home at 65 Albion Street, East Brunswick. I registered the baby at Albury when he was about 18 days old. I named him Leslie Neil Stevens. When I took the baby to the Home I agreed to pay 10/- per week to the Childrens’ Welfare Department for his upkeep. I have paid this amount regularly weekly out of money which I earned whilst in service at Elwood. I was earning 22.6 per week.”

Rekindled romance

It was during this time that she became reunited with Eugene Rollings. He visited her in Melbourne three times before they decided to get married in early January 1935.

According to the court proceedings, when Eugene found out about her baby he told Mary Alice he would not keep another man’s child.

The day of the murder

Mary Alice admitted she was terribly worried over this and did not know what to do with the child. What she resorted to was recorded in her statements to police on Boxing Day 1934:

“I left my employment on 19.12.34 with the intention of going to Albury to marry Eugene Rollings. After I left my employment at St Kilda I went and stayed at Fitzroy for three nights. On Friday afternoon 21.12.34 I went to the Childrens’ Welfare Department and paid three shillings I owed for the child. I told them I was taking the child and I obtained permission in writing to get him from the Home.

“I arrived at the home at about 10 minutes past 5. I saw Sister Sprague at the home and after saying goodbye to the sisters and girls at the home Sister Sprague and another lady drove me in a motor car with the baby and a suitcase to the tram at the corner of Lygon and Albion Street, Brunswick. I went to Bourke Street on the tram. I then went with the baby to Coles and had tea. I then came to Bourke Street and got on another tram and went to Princes Bridge.

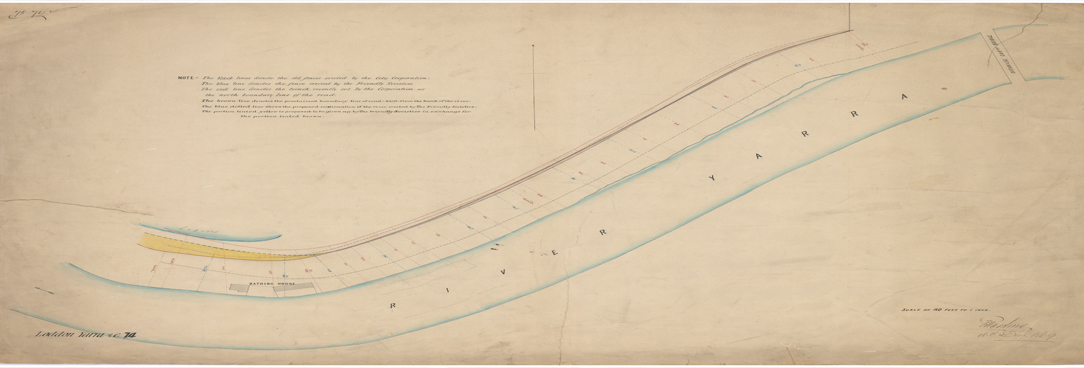

“When I got back in the city from Brunswick I decided to drown the baby as I had no place to take him. I only had enough money for my fare to Albury. After getting off the tram at Princes Bridge I walked along the Yarra River upstream on the north side for a considerable distance to a seat which I pointed out to detectives today. I sat on the seat and nursed the baby for about two hours wondering what to do with him.

“During that time I took the blue jumper suit and cap off him and put on the brown jacket produced in its place. I give no reason why I did this. I then carried the baby and the suitcase further along the river and when I came to a spot which I pointed out to the detectives today I stopped. I could see nobody about and I then threw the baby into the river face downwards. I saw him drop into the water. I did not hear him cry and I immediately left and walked back to Collins street with my suitcase. It would be about half past 10 o’clock when I threw my baby into the water.

“I then went back to the room at Fitzroy and the following morning I caught a tram at 8 o’clock and went to Albury. I stayed at Eugene Rollings’ home until interviewed by police today. I did not tell anyone what I had done with the baby. When Eugene Rollings asked me on Tuesday Christmas Day what I had done with the baby I told him that some person had adopted it but I did not know their names.

“At no time did the father of my child give me a penny towards the support of the baby. This statement which has been read over to me was made on my own free will and is true and correct. Alice Stevens.”

A ‘not guilty’ plea

At trial, however, Mary Alice Clara Stevens pleaded ‘not guilty’ and said in a statement from the dock:

“Your honour and gentlemen, I am innocent of any intention of killing my boy. I loved him and wanted to keep him under most distressing circumstances. I never thought of doing such a thing and I did not intend to do it. Since he was born my only thought and idea was to rear him to the best of my means. My mind for months became disturbed. I was in distress and began to lose any grip I had of myself. I tried to get him adopted by somebody who would care for him and look after him, and where I could see him frequently.

"I often went to the Travellers’ Aid Society and had my meals there. Occasionally I met a friend there whom I knew as Miss Gilbert, who lived in the Parade, Ascot Vale. She promised to look after my child if her parents did not object, or to get a friend to do so. The reason I took the boy from the Home that day was because I made arrangements to meet her at the Travellers’ Aid Club rooms, or rather she promised to meet me at the GPO herself the following night and arranged to take the boy herself or to get a friend of hers to take him. I can remember bringing the child to the City. I waited for hours to meet my friend. She did not come, and I grew ill and depressed and dejected.

"I have no memory of where I went or what I did from then on. I loved my boy dearly that night, as much as I had ever loved him. I would not have destroyed him and never intended to do so. Since my arrest I have been in prison. The statements I made have been read to me. They are not correct. I am telling the truth now. I never at any time intended injuring or destroying my boy when I took him away from Mission Home. I am unable to tell you my feelings in regard to the dreadful charge made against me. I am innocent of murder.”

The jury’s finding

The jury deliberated for five hours before finding Mary Alice Clara Stevens guilty of murder with a very strong recommendation to mercy.

Sentence to death was then passed by the Judge.

Petition for mercy

In the petition for mercy that followed, arranged by Mary Alice’s fiancé Eugene, signatures were accompanied by a letter that said “we make no attempt to justify her action but desire to respectively express the opinion that if the law compelled the father of the murdered child to share in the responsibility of maintaining the child, such a desperate act would have been avoided.”

- Sentence reduced to three years

Cold-blooded

The Inspector General disagreed with this view and claimed Mary Alice to be a cold-blooded killer.

“She is the stuff of which murderers for gain are made. She shows few signs of being moved by joy or sorrow, anger and hatred, or love and affection. She appears entirely self-centred.”

He reports a female officer’s observations:

“She was perfectly calm and collected during the Court proceedings. She was quite cheerful, ate well, and discussed the incidents of the trial with me. When the verdict was given she went limp and dead and then screamed twice. A few minutes later she said, ‘How could they? How could they? I did the best for the child when I had it.’ It was fear she felt. For the first time she realised what the consequences might be. She quickly recovered. It did not appear that she realized that the killing of the baby was a crime. My knees knocked and my heart turned over. The main thing in my mind was the murder; but I am certain it was not in hers. She is not a normal woman. The impression she leaves with me is that of a person who has drowned a cat or a dog.”

While Miss Wall, the Matron was quoted as saying:

“She shows little emotion. Neither grief nor sorrow touch her much. When first received she told me all about the crime keeping nothing back – all without emotion. She behaved quite normally with other prisoners on remand talking and laughing.

"When questioned as to the consequences to herself of her actions she said I did not think of them at the time. I first realized that something might happen to me when I was arrested.”

The finding

In spite of the Inspector General's letter, the Premier’s Office recommended on the 9th of April 1935 that Mary Alice Clara Stevens’ death sentence be amended to three years imprisonment.

This was Approved by the Governor in Council on the same day.

* VPRS 1100 / P0002 / unit 000007 / Type M2

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples