Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, sex work in Victoria was controlled indirectly through laws against drunkenness, disorderly behaviour, vagrancy, and having no visible means of support.

Sex work itself was not illegal in Victoria until streetwalking became a criminal offence in 1891, and living off the earnings of prostitution was banned in 1907. Over the next thirty years, brothels across Melbourne were systemically shut down. Despite these measures, sex work continued.

By the 1970s, massage parlours operating as brothels and streetwalking in suburbs such as St Kilda posed increasing risks to women’s safety. When John Cain Jr took office as Premier in 1982, it was clear reforms were needed.

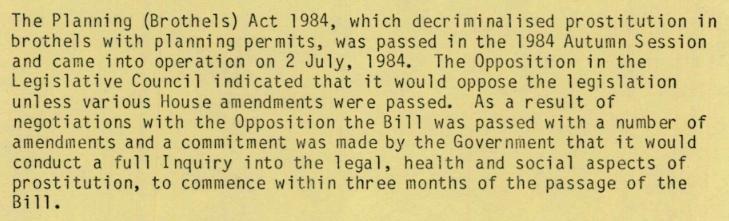

In response, two Acts were introduced in the mid-1980s related to sex work: the Planning (Brothel) Act 1984 and the Prostitution Regulation Act 1986. Records relating to these Acts are available in the recently opened Cabinet papers at PROV.

Reflecting on his time as Premier, in the book Trials in Power, John Cain Jr said:

“…some things we did because we believed in them. These were the things that it might have been easy or more politically rewarding to side-step, but we chose not to.”

John Cain Jr cited reform of Victoria’s sex work industry as one example of legislation that his government believed in and worked towards despite opposition.

Cabinet working party

In June 1983, the Victorian cabinet appointed a working party to investigate how the locations of brothels throughout the State could be better regulated.

As a result of this, in 1984 preparation began on a Bill to decriminalise prostitution in brothels with planning permits. In Trials in Power, Katrina Gorjanicyn, political science academic, states:

“The Planning (Brothels) Act 1984, aimed at controlling prostitution through town planning regulations, was the state government’s first step towards decriminalising prostitution-related activities. However, it increased a distinction which already existed between different forms of prostitution in Victoria.

On the one hand, because the Planning (Brothels) Act 1984 abolished criminal penalties for prostitution in brothels, a brothel-owner with a town planning permit who made money from prostitution was acting within the law. On the other hand, managers of escort agencies, a person living on the earnings of a prostitute involved in street soliciting, and a prostitute working from her own home, all could be convicted of criminal activities.”

The Neave inquiry; Rethinking sex work in Victoria

In response to growing concerns, the working party called for an inquiry into Victoria’s sex-work industry as a whole.

The government established the Neave Committee of Inquiry, chaired by judge, commissioner, law reformer, policy maker and academic Marcia Neave. Neave would later become the inaugural chair of the Victorian Law Reform Commission in 2004, where she oversaw reforms to criminal laws and procedures around sexual assault.

By 1984, estimates suggested there were between 3,000 and 4,000 sex workers across Victoria, both male and female. The industry was divided into four main types of sex work including: street soliciting, brothel work, private premises, and escorting services.

Of these, approximately 200 sex workers were engaged in street soliciting, concentrated mainly in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda. The majority worked in brothels or escorting agencies.

The 462-page Neave report – a landmark document – found that regulation around brothel locations and licensing were needed. It argued that criminal penalties should focus on protecting adults and young people from violence, sexual abuse, exploitation, and intimidation. However, the report stopped short of recommending blanket decriminalisation. Instead, it maintained that street solicitation should remain a criminal offence unless permitted within designated Council areas.

According to a government Cabinet and Cabinet Committee Submission, the response to the release of the Neave Report was positive:

“Editorial and other media comment in the days after release of the report was generally favourable. The Age described the report as presenting a ‘realistic view of prostitution.’

The only proposal it opposed was that relating to the possibility of allowing street areas where soliciting could occur lawfully. Otherwise, it praised the report as carefully reasoned and in keeping with enlightened public policy and majority community opinion. The Herald also singled that recommendation out as its most serious criticism of the report…”

Prostitution regulations: reform or restraint?

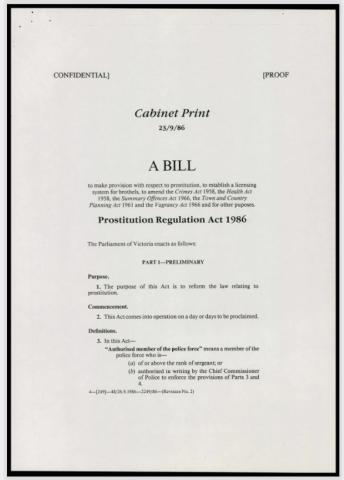

In the wake of the Neave Inquiry, the government sought to address Neave’s recommendations through the Prostitution Regulation Act.

As Katrina Gorjanicyn argued:

“…although the Prostitution Regulation Bill (1986) made some attempt to prevent the exploitation of prostitutes and to decriminalise a number of prostitution-related activities, it fell short of being radical. In retaining prohibitions on street soliciting but permitting prostitutes to work in licensed brothels, the bill adhered to the tradition of containing and institutionalising prostitution.”

Gorjanicyn also observed that community reactions were mixed.

The industry itself welcomed certain reforms but pressed for better conditions in brothels and full decriminalisation.

The police raised concerns about corruption, criminal control, and drug activity within brothels.

Despite these debates, reforms stalled and went no further.

Raelene Francis, Emeritus Professor of History at the Australian National University and author of Selling Sex: A Hidden History of Prostitution, told PROV that full decriminalisation was dismissed in Victoria due to several community concerns at the time.

"There was a big concern about street soliciting and drugs at the time, and also about the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Providing a legal option for sex workers in brothels seemed a better solution to both worker health and safety and public order."

However, Francis said this model ultimately created a divided industry.

"The provision for licensed brothels created a two-tier system within the sex industry with those working in the legal brothels generally having safer, healthier conditions. As the number of sex workers increased relative to the number of places available in legal brothels, competition for these legal places increased. This gave more power to the owners/operators of the legal brothels which to some extent offset the benefits of working legally.

The fact that sexual services could only be sold legally in these brothels and within a few limited street locations meant that the legal opportunities for independent operators, working alone or in partnership with other workers, were almost non-existent. In other words, to sell sexual services legally, workers had to become employees."

Decades later, Gender Equality Victoria, in its submission to the 2020 Review into Decriminalisation of Sex Work, highlighted these as enduring consequences of partial reform:

“...some people are employed legally through licensed brothels and escort agencies, with access to workers’ rights and protections, while others – such as people in unregistered brothels or working on the street – have no workplace protections forcing them to work in physically dangerous circumstances, risking criminal convictions and a cycle of violence, poverty and further crime.”

From Cain to today: Sex work and social reform

Though John Cain Jr’s government never fully decriminalised sex work in Victoria, its reforms to legalise aspects of the industry were widely viewed as one of his great achievements. In their obituary for the former leader, Inside Story listed legalisation of sex work among his government’s enduring social policy successes.

According to Francis, the Victorian model of legislation was unusual nationally at the time.

"The Victorian model of legalisation was unique in Australia at the time, although NSW was soon to follow a similar approach in relation to brothels. NSW was more radical than Victoria in decriminalising street soliciting in 1979, with amendments in 1983 which placed some restrictions on where such soliciting was legally permitted."

But Victoria soon caught up.

Today, all sex work in Victoria is decriminalised thanks to the passing of the Sex Work Decriminalisation Act in 2022. According to Consumer Affairs Victoria:

“The Victorian government has decriminalised sex work to achieve better public health and human rights outcomes…every worker in the industry is entitled to the same treatment and protections under law, with rights to call out discrimination and unsafe workplaces or practices…Criminal offences to protect children and workers from coercion and address other forms of non-consensual sex work continue to be enforced by state and federal law enforcement agencies.”

View the records: Victoria’s sex work reform revealed

On 1 January 2026, Cabinet records relating to sex work reforms during the John Cain Jr era were officially opened. These documents shed new light on the debates, decisions, and policies that shaped Victoria’s approach to sex work.

Explore the Cabinet records now to see the sources behind this article. Records referenced here include:

- Cabinet and Cabinet Committee Submissions, VPRS 11944 P1 Box 29 No. 1275, Prostitution Inquiry

- Cabinet and Cabinet Committee Submissions, VPRS 11944 P1 Box 43 No. 1952, Prostitution Inquiry

- Cabinet and Cabinet Committee Submissions, VPRS 11944 P1 Box 49 No. B2246, Prostitution Regulation Bill

- Cabinet and Cabinet Committee Submissions, VPRS 11944 P1 Box 49 No. 2246, Prostitution Inquiry: Government Response.

Other references

- Trials in Power: Cain, Kirner and Victoria 1982-1992, Edited by Mark Considine and Brian Costar, 1992

- GEN VIC Submission to the Inquiry into the Decriminalisation of Sex Work, Gender Equality Victoria, 2020

- Decriminalising Sex Work in Victoria, Consumer Affairs Victoria, last updated 2025

- John Cain was a Leader of Integrity, Courage and Vision…And Still He Lost Victoria’s Top Job, Tim Colebatch, Inside Story, 2019

Raelene Francis' book Selling Sex: A Hidden History of Prostitution provides the first comprehensive history of prostitution in Australia from European colonisation to 2007.

Continue exploring Victoria’s political evolution

Discover more in-depth details of the Cain-Kirner era by delving into the Cabinet records.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples