Author: Paul Strangio

Emeritus Professor of Politics, Monash University

The release of Cabinet Papers and the value of historical transparency

For a time, I was the visiting Cabinet historian at the National Archives of Australia, a role focussed upon the annual release of Commonwealth Cabinet papers on New Year’s Day, an event that always generates considerable media coverage. Its commendable and overdue that the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) are now emulating that practice for State Cabinet papers, as have other states.

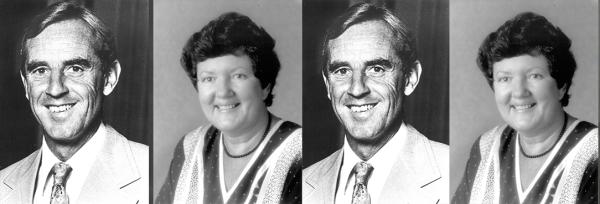

I should also say that I’m vitally interested in the Cain-Kirner governments, having done research on the history of the Victorian Labor Party and written brief biographies of Victorian premiers, including John Cain snr, three times premier of the state in the middle of the twentieth century, and father, of course, to John Cain jnr, premier from 1982 to 1990. As an aside, you might know that John Cain jnr’s son, another namesake, John Cain, is the incumbent State Coroner of Victoria.

It’s worth asking whether there is a family which has performed more public service for this state than the Cains? Theirs is an extraordinary record of civic dedication.

Who was Victoria’s most Impactful modern premier?

Another question for you: who in the modern era of politics (an age conventionally identified as beginning in the 1970s and heralded federally by the arrival in office of Gough Whitlam in 1972) has been Victoria’s most impactful premier? We are apt to these days to ring our hands about the quality of political leadership. Yet I’d suggest that over the past half century this state has had four highly consequential premiers: Rupert Hamer (1972-81), John Cain (1982-90), Jeff Kennett (1992-99) and Daniel Andrews (2014-2023). You will have your own opinions about those leaders, but it’s indisputable that each left a major imprint on the state. We could probably debate all day long what measures we ought to apply in assessing the influence of a head of government but, of that group of four premier titans, I think there is a substantial case that Cain has been the most transformative. He indelibly changed the state on at least two levels.

Joan Kirner and the challenges of leadership in crisis

Briefly, what about Joan Kirner, Cain’s successor, and premier from 1990 to 1992? Kirner will always have an important niche in Victorian political history because of her status as the state’s first female premier. But hers was predominantly a fag end administration. She took over from a broken Cain in August 1990 when the Labor government was dying on its feet and sliding to inevitable electoral defeat. Her two years in office largely comprised crisis management as she strived mightily to stabilise Victoria’s ailing economy, hold together a restive party and parry the trade union movement. Her chief legacy as premier was selling the debt-laden State Bank of Victoria to the Commonwealth Bank, following negotiations with the federal treasurer, Paul Keating.

Kirner had angled to succeed Cain in 1990, but there was a strong element of the glass-cliff syndrome about her premiership: a woman leader inheriting office in impossible circumstances.

Setting the scene: Australia and Victoria in the 1980s

For those too young to have lived through the Cain era (I had my first vote at the election that brought him to office), I should very briefly set the scene. In his book The Eighties, historian Frank Bongiorno writes, ‘it is the era of big hair and shoulder pads, synthesised pop and “greed is good”, of Michael Jackson, Madonna and Ronald Reagan, of British boy and girl bands, Live Aid for Ethiopia and Margaret Thatcher … It is the decade that began in the shadow of the bomb and ended in the joyful dismantling of the Berlin Wall.’

The latter event, which was followed in 1991 by the dissolution of the Soviet Union, was so much a geopolitical earthquake that the American political theorist, Francis Fukuyama, famously asserted that humanity had reached ‘not just … the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but end of history as such. That is, the end-point of humankind’s ideological evolution and universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of government.’ Fukuyama was, of course, spectacularly wrong.

Defining events of the era: Culture, crisis and change

In Australia, some of the events that defined the period were the feel good 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games, the 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires, Australia II’s victory in the America’s Cup, the battle against the AIDs epidemic, and the Bicentennial of 1988. During that era, we also saw wild gyrations in media ownership epitomised by Murdoch gobbling up the Herald and Weekly Times and Kerry Packer selling the Nine Network to Alan Bond and buying it back three years later for $1 billion less. It was also the time of the 1987 Stock Market crash and the severe recession of the early 1990s.

On television Australians were watching Perfect Match, Neighbours and Home and Away, all premiering during the 1980s. So, too, did The Movie Show on SBS and Media Watch on the ABC. Among the biggest movie box office hits were Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Beverly Hills Cop and Crocodile Dundee and their sequels, while popular Australian films were The Man from Snowy River, Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome, Phar Lap, The Year My Voice Broke and Strictly Ballroom.

International acts Madonna, Bruce Springsteen, Michael Jackson and George Michael topped the music charts, but it was also the era of John Farnham’s Whispering Jack, Men at Work’s Business as Usual, Midnight Oil’s 10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1 and Diesel and Dust and INXS’s Kick.

The Hawke–Keating era and the transformation of Australia

Above all, it was the time of the Hawke-Keating Labor federal government, arguably the most successful political tandem in Australian political history. Vastly different, they were leaders of compelling complementary talents. They led what is remembered as, perhaps inflated by mythology, the gold standard of reformist governments. Labor internationalised the economy through the application of market forces but Australia’s encounter with neo liberalism was distinctive with the reform project cushioned by meliorative measures such as Medicare, universal superannuation and a partnership with the trade union movement.

In the influential interpretation of the journalist and writer, Paul Kelly, it was the era that marked the ‘end of the Australian Settlement’: the dismantlement of the suite of institutions and policy orthodoxies that had governed the nation’s life since the early federation.

How the Cain government reshaped Victoria: Reform, renewal and a lasting political legacy

What of Victoria? As I noted above, the Cain Labor government, elected in a watershed result elected in April 1982 was transformative in at least two ways. First, it catalysed a dramatic change in electoral behaviour and in the fortunes of Labor in this state. For the majority of the twentieth century, Victoria was the Cinderella of Australia’s state Labor branches: it was the last to win office and its share of government was less than half that of the New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmanian and Western Australian branches.

Splitting over the combustible forces of communism and Catholicism in 1955—a schism that destroyed a government led by John Cain snr—Labor was thereafter confined to opposition for a generation. Victoria earned the epithet of the ‘jewel in the Liberal crown’ during the extended ascendancy of Prime Minister Robert Menzies and Premier Henry Bolte in the 1950s and 1960s.

Why the Liberal dominance was not about ideology

Was there a particular affinity between Victorians and the Liberal Party during that era? From close analysis of the electoral evidence, I’ve concluded that there was not. Rather, the Liberal supremacy was chiefly a function of the fact that Labor was unelectable.

Post-split, the party ossified into a doctrinaire moribund outfit dominated by Trades Hall based industrial militants who were wilfully uninterested in winning government. Gutted of talent, riven by animosities and demoralised, the parliamentary party drifted impotently. (Sound familiar?)

The reformers who rebuilt Victorian Labor

Cain was part of a small group (it included other remarkable figures such as John Button, Barry Jones and Race Mathews) who were in the vanguard of a campaign to reform Victorian Labor from the 1960s. They bravely challenged the ruling clique (the reformers referred to it as ‘the Junta’) and, aided by the federal Labor leader from 1967, Gough Whitlam, they were instrumental in precipitating a far-reaching reorganisation of the branch in 1970-71. This gradually paved the way for an infusion of new blood into the parliamentary party (Cain was part of that influx), and for a comprehensive renovation of Labor’s policy program to make it electorally viable and prepare it for office.

Breaking the nine election curse: Cain’s 1982 victory

When Cain became state opposition leader in 1981, his mission was to end Labor’s woeful record of nine—yes, nine—successive election defeats.

On polling day on 3 April 1982, one sceptical voter told Cain, ‘You’re like Collingwood. If you don’t get it this time you never will.’

The jinx was broken: Labor swept into office with a primary vote of 50 per cent. The sense of providence surrounding that victory was palpable: Cain was the first Labor premier since his father 27 years before. His government proceeded to win two further elections. In doing so, Cain became the first Labor leader in the state’s history to govern for consecutive terms, and the fourth-longest-serving premier of the 20th century.

More than that, his government at long last proved that Labor could manage the state productively. Since then, as you are aware, Labor has become Victoria’s natural party of government: it’s been in office for three-quarters of the past four and a half decades and has won nine out of twelve elections. It is no exaggeration to say that the Labor premiers who followed Cain this century—Steve Bracks, John Brumby, Daniel Andrews and Jacinta Allan—stand on his shoulders.

Modernising Victoria: Cain’s second great legacy

The Cain government’s second great legacy was its modernisation of Victoria. To some respect, it built on directions initiated by the Liberal Party’s Rupert Hamer, premier between 1972 and 1981, a leader appropriately dubbed by his biographer, Tim Colebatch, the ‘liberal Liberal’. Hamer and Cain undeniably were on an ideological continuum, one a progressive social liberal and the other a committed social democrat. They were also politicians with an abiding respect for each other.

Yet the reform record of Cain’s eight-year premiership was remarkable for its range and significance in its own right.

Reforming government: Transparency, accountability and modern administration

From the outset, Cain professionalised and systemised the hitherto ramshackle and antiquated executive government processes, among other things, establishing a Cabinet Office for the first time, along with reorganising and invigorating the Department of Premier and Cabinet. As an activist attorney-general, Cain spearheaded legal and electoral reforms underpinned by the principles of transparency, accountability and independence from political interference.

The government was pioneering in Australia in creating a Director of Public Prosecutions and in enacting freedom of information (FOI) laws. It rid Victoria of a malapportioned zonal voting system, and instead enshrined the principle of one vote, one value. An independent, non-partisan authority was established to oversee the state’s electoral system—a model emulated federally when the Hawke Labor government created the Australian Electoral Commission.

Reshaping parliament and strengthening democratic stability

Though frustrated in its attempts to transform the Legislative Council because it did not have the numbers in that chamber, the Cain government legislated maximum four-year terms for the Legislative Assembly (the first three years fixed) and, for the first time, linked the lower and upper house terms. Experts hypothesised that this alteration of bicameral relations had removed the ability of the Legislative Council to block supply—a power that it had wilfully exercised in the past, including to destroy the second of John Cain snr’s administrations in 1947. It was another of the ghosts that haunted his son.

Building modern public institutions: TAC, WorkCare and VicHealth

Cain’s government established the Transport Accident Commission (TAC) and WorkCare (the forerunner of WorkSafe). Both schemes were administered by a single public authority (overturning the old model of profit-driven private insurers) -- and ushered in an innovative emphasis on accident prevention.

Another creative initiative of his premiership copied interstate and internationally was the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth). Founded by legislation that prohibited outdoor tobacco advertising, it used revenue from cigarette taxes to fund public health campaigns, and to buy out tobacco sponsorship of cultural and sporting events.

Social reform, cultural change and urban renewal

The government passed landmark equal opportunity legislation, and Cain took on Melbourne’s stuffiest establishment sporting clubs over their maintenance of exclusively male zones.

He spurned invitations where his wife, Nancye, could not accompany him, and threatened action unless the clubs abolished these archaic practices.

The Melbourne Cricket Club and Victorian Racing Club bowed to his pressure. Cain’s government legalised brothels, liberalised licensing laws, tightened firearms controls, overhauled tenancy laws, and extended shop trading hours.

Joan Kirner, an active Conservation and then Education Minister, was responsible for pioneering Landcare, a policy innovation taken up in other states, and inaugurated the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE), a major and enduring revamp of upper-level secondary schooling. Labor’s visionary minister for environment and planning, Evan Walker, oversaw the development of Southbank and Melbourne’s sporting precinct. A pet project of Cain’s was the National Tennis Centre at Flinders Park (now Melbourne Park), which became permanent home to the Australian Tennis Open.

The crises, conflicts and financial failures of Cain’s final term

Cain’s government had its share of mistakes. It was stricken in its final term by wrenching public-sector industrial disputes and bitter internal factional conflict, and the state was beset by a series of financial calamities. The latter were due to a combination of the government’s imprudent policies, corporate venality (the era of buccaneers like Christopher Skase, Bond and so on) and excess licensed by federal Labor’s deregulation of the financial sector, and neglect by regulators.

Though a far-reaching moderniser of his party and Victoria, this period showed up Cain as in many ways an ‘old’ Labor figure: he retained a traditional aversion of markets with their ways distasteful and mysterious to him. Conversely, he was too well schooled in Victorian Labor’s cannibalistic past. He had a deep ingrained loathing for intra-party sectarianism which manifested in an aloofness from the factions—a position that left him vulnerable as those factions turned feral in his final term.

The result was tragedy for a leader who was such a stickler for probity (he returned corporate gifts, declined to fly first-class, and paid for his own postage) to see his government’s reputation so sullied in its final years. Indeed, the end of his premiership had echoes of what had befallen his father: a government devoured by its own.

A lasting verdict: Cain’s enduring contribution to Victoria

Notwithstanding its unhappy conclusion, in my view there’s no question that the Cain government changed Victoria overwhelmingly for the better. It did so with seriousness of purpose, clarity of principle integrity and decency, which were hallmarks of its premier.

Continue exploring Victoria’s political evolution

Discover more in-depth details of the Cain-Kirner era by delving into the Cabinet records.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples